Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in

Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

Francisca Sousa

1a

, Leonor Tejo

2b

, Sunny Miranda

2c

and Paula Alexandra Silva

2d

1

Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Coimbra, Portugal

2

Department of Informatics Engineering,

University of Coimbra, CISUC/LASI – Centre for Informatics and Systems of the University of Coimbra, Portugal

Keywords: Gender Balance, Women in Informatics, Mentoring, Digital Content, Social Media.

Abstract: Gender disparities in Informatics persist as a significant issue, with women facing barriers to entry, retention,

and advancement. Mentoring programs hold the potential to improve this issue. Because change demands a

collective response, this study explores how to shape the digital content of mentoring programs to support the

students, women and men, in an Informatics department. This work builds upon the findings of a focus group

study, complementing them by applying a questionnaire to gain insight into students’ academic experiences,

perceptions of the benefits of a mentoring program, and preferences concerning digital communication

platforms. Findings indicate that the digital content of mentoring programs can help in three keyways:

providing insights into the job market, shedding light on career and recruitment processes, and offering real-

life content. These findings are valuable to departments and mentoring programs that wish to support women

in Informatics through the digital content of their websites and social media platforms.

1 INTRODUCTION

In today's fast-changing technological environment,

diverse teams are recognised for their creativity,

problem-solving skills, and better decision-making

(Webb, 2023). Furthermore, increased female

participation in the tech sector is one solution to

address the shortage of professionals needed for the

EU's digital sector to thrive, potentially boosting

economic benefits such as GDP per capita (De Luca,

2023). Considering these factors, one would expect a

higher participation of women in the technology

sector; however, the situation in Europe shows

different figures. Despite efforts to engage women in

the workforce, their representation in the technology

field has seen limited growth over the last decades

(Webb, 2023) and women continue under-

represented in the field of Informatics across

educational and professional levels (Blumberg et al.,

2023).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-6346-8118

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9842-3105

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4916-5618

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1573-7446

Research shows that mentoring programs

positively impact women in Informatics, personally

and professionally (Boyer et al., 2010; Aufschläger et

al., 2023) namely by boosting women's self-

confidence (Happe et al. 2021) and their confidence

in their technical skills and leadership abilities (Boyer

et al., 2010). Research also highlights that women

turn to their social networks and online resources for

career advice and guidance (Paukstadt et al. 2018).

However, to our knowledge, no study has

investigated how mentoring programs can leverage

their digital platforms to support women in

Informatics better, and the specific content social

networks and online resources should provide to

support them in their professional journeys

effectively.

INSPIRA is a mentoring programme within the

Department of Informatics Engineering at the

University of Coimbra in Portugal, whose goals are

to attract, support, and retain female students,

researchers, and academics in Informatics. A prior

Sousa, F., Tejo, L., Miranda, S. and Silva, P. A.

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0013286000003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 931-941

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

931

focus group study (Sousa & Silva, 2024) conducted

with women from the department explored the

challenges they faced, practical solutions to those

challenges, and the potential of the INSPIRA

mentoring programme and its online presence to

support them in their career in Informatics.

The findings revealed that a mentoring

programme with content tailored to their needs could

support women in Informatics, for example, by

offering mentorship and peer support opportunities,

providing access to professors who can offer

guidance and inspiration, sharing testimonials from

former students and graduates, and organising

workshops and networking events. The focus group

study also found that the mentoring programme could

be a valuable resource for navigating academic and

organisational issues, such as those related to going

on Erasmus and finding the correct instructions and

informational resources. However, some of the

challenges found though the focus group are not

exclusive of women. Furthermore, gender imbalances

in Informatics require a cultural change and collective

response (Widdicks et al., 2021; Frieze &

Quesenberry, 2015).

This study takes a step further, in relation to our

previous focus group study, to identify the challenges

the department's student community, man and women,

faces and determine the types of content that the

mentoring programme should provide and whether

those contents are better suited for the program's

social networks or website online resources. To

address those goals, we distributed a questionnaire

among students from the department to identify

challenging moments and the specific ways in which

a mentoring programme and its digital content could

be helpful and to understand participants' digital

communication habits and use of social media

platforms. We also explore whether there are

differences between genders.

Having analysed the results of the questionnaire,

this study contributes content recommendations for

websites and social media of mentoring programs for

women organised into user goals, according to

Norman's Three Levels of Design (Norman, 2007)

and Cooper's Goal-Directed Design (Cooper et al.,

2014).

These findings are valuable to departments and

mentoring programs that wish to support women in

Informatics. The methodology provides a framework

that other institutions can adapt to their unique

contexts.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

2.1 Women in Informatics

The under-representation of women in Informatics is

an ongoing global challenge. Despite progress in

promoting gender equality, women in senior roles

within STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering,

and Math) fields are still limited (Funk & Parker,

2018) and remain male-dominated. According to

Eurostat (2024a), from 2013 to 2023, the number of

ICT specialists in the EU increased by 59.3%, almost

6 times as much as the increase (10.7 %) for total

employment. Nevertheless, in 2023, only 17.4% of

the people employed in the EU with an ICT

background were women, a percentage that saw a

decrease of 1.4 points from 2016 (Eurostat, 2024b).

In 2023 in Portugal, only 14,2% of women with an

ICT education are employed (Eurostat, 2024b).

The McKinsey report projects a tech talent

shortage of 1.4 to 3.9 million tech professionals by

2027 (Blumberg et al., 2023). Women currently hold

only 22% of tech positions in Europe; however,

increasing the proportion of women in tech to 45% by

2027 could close Europe's talent gap and potentially

boost GDP by €260 billion to €600 billion. Women's

underrepresentation in tech is particularly troubling

because the roles with the lowest female participation

are expected to see the highest demand in the coming

years. For instance, women constitute 19% of the

software engineering and architecture workforce;

they only comprise 10% of cloud solution architects

and 13% of Python developers—two of the most in-

demand roles (Blumberg et al., 2023). Where no

single solution has been found to address these

imbalances, interventions could enable women in

tech to thrive at work, give women a reason to stay in

tech, ensure women are in tech roles that matter, and

address STEM drop-off in university, namely through

mentoring (Blumberg et al., 2023).

2.2 Mentoring for Women in

Informatics

Mentoring programs are touted as one approach to

addressing the gender gap, broadening participation,

retaining students, and supporting women’s success

in computing (Boyer et al., 2010; Aufschläger et al.,

2023). There are several types of mentoring,

including formal and informal mentoring, as well as

peer and group mentoring (Aufschläger et al., 2023),

however mentoring typically involves a relationship

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

932

where a more experienced person gives strategic

advice to facilitate the academic, professional, and

personal development of another, less experienced

one (Meschitti & Lawton Smith, 2017).

Petean and Rincon (2024) studied mentoring

programs in Austrian and German universities to

support women in STEM, particularly in the graduate

and early career stages. They highlighted that

effective mentorship relies on customised approaches

tailored to mentees' goals, strong leadership support,

and institutional backing. Critical factors for success

include fostering supportive, reciprocal mentor-

mentee relationships and providing personalised

access to resources and networks through matching

and outreach efforts like training workshops and

webinars to emphasise networking and knowledge

sharing.

Singh and Basu (2021) established a mentorship

programme at a high-research US university aimed at

reducing the gender gap in tech and enhancing

diversity in computing. The initiative paired female

undergraduate CS students with corporate mentors

for career guidance, including resumé critiques, mock

interviews, and arranging workplace visits.

Interviews with mentees revealed that the programme

positively impacted both personal and professional

aspects of mentees. Personally, the programme

fostered a sense of belonging, boosted confidence,

and helped mentees connect with role models.

Professionally, the programme motivated participants

to continue to pursue a career in computing, expanded

their network, and exposed them to career

opportunities.

The Computing Identity Mentoring (CIM) (Boyer

et al., 2010) was implemented in three U.S

universities and aimed to bolster students computing

identity to improve retention rates among computing

majors and develop their technical and leadership

skills. Results of a survey showed that participants

reported greater technical skills, improved computing

knowledge, confidence in leadership, and

commitment to computing careers compared to non-

participants. The CIM mentoring model also

benefited both mentors and mentees, where mentors

received training, took on leadership roles in

mentoring and service projects, and mentees

benefited from educational and social support.

While Petean and Rincon (2024) emphasise

programme flexibility and the importance of a

customised approach, Singh and Basu (2021) showed

how mentoring with corporate mentors impacted

students' personal and professional spaces. Boyer et

al. (2010) show how mentoring can impact students'

perception of their technical and leadership abilities

in computing. These studies underscore the benefits

of mentoring to improve gender balance in

Informatics, however, they also stress that mentoring

should be tailored to the specific institutional and

cultural contexts, underlining the need for further

research and methodologies to determine the specific

need mentoring programs, which this paper seeks to

provide.

2.3 From Programme Design to Digital

Content for Women

There is a variety of aspects that need to be considered

when designing a mentoring program. Aufschläger et

al. (2023) studied how mentoring programs need to

be designed to contribute to reducing the gender gap

in Informatics. Through analysing 13 empirical

studies carried out between 2013 and 2022, the

authors identified 21 factors, that they organised into

three types of aspects, to consider when designing

mentoring programs for women in Informatics:

relationship aspects such as emotional, moral and

psychological support in achieving career and family

goals; content-related aspects that include having a

mentor as an advisor, and creating opportunities for

professional exchange; and organisational aspects

such as time management and setting up a predefined

structure and activities within the program.

While Aufschläger et al.’ (2023) study enables an

understanding of how mentoring programs need to be

designed to cater to the needs of women in

Informatics, the types of contents they could benefit

from in their careers is unclear. Paukstadt et al. (2018)

conducted a focus group study with female students

on career guidance websites aimed at young women

in IT to understand how online platforms could meet

women's needs. Participants showed a preference for

concise and relatable content featuring female role

models, along with visually appealing layouts that

encourage interaction. Based on these findings, the

authors developed five design recommendations for

platforms targeted at women in IT: provide engaging

content featuring relatable female role models;

develop serious mini-games linked to real IT tasks for

hands-on experience; offer an online test to help

young women identify their strengths and interests in

IT careers; use gender-specific language, content, and

imagery; and present selected IT careers in detail with

interactive examples to aid in understanding job roles.

Paukstadt et al. (2018) provides valuable guidance,

however these are not enough to determine the types

of contents and the specific platforms where those

contents should be made available nor how these

enable women to address their multi-level goals.

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

933

3 APPROACH AND METHODS

3.1 Prior Work

This work builds on the findings of a focus group

study (Sousa & Silva, 2024) conducted with women

from the Department of Informatics Engineering at

the University of Coimbra in Portugal. That study

explored the challenges women face in their academic

journeys in Informatics and how a mentoring

programme and digital media content could

effectively address and support women in

overcoming those challenges.

The findings revealed that a mentoring

programme could support participants by offering

mentorship and peer support opportunities,

facilitating access to professors who can offer

guidance and inspiration, creating tailored digital

content through a website, and supporting specific

challenges. Specifically with regards to the types of

content that the mentoring program's website and

social media platforms could provide, this study

concluded that digital media could include

testimonials and success stories, guidelines and

academic support, informational resources,

networking and contact information, events and

workshops, and online courses and links external

resources. However, this focus group study did not

clarify whether other students in the department

experienced the identified challenges, how the

mentoring programme website and social media

could support the student community, or how the

student community engaged with social media.

3.2 Goals, Instruments, and

Procedures

In the scope of the INSPIRA mentoring programme

of the Department of Informatics Engineering of the

University of Coimbra, in Portugal, this work sought

to determine the types of content that could support

the department’s student community and the specific

digital platforms those contents should be made

available. Four research questions (RQ) guided this

study: RQ1 - What challenges do students, regardless

of gender, face in their academic journeys? RQ2 - To

what extent do students perceive a mentoring

programme as beneficial? RQ3 - How can the online

presence of a mentoring programme serve as a

supportive tool for the entire department? and RQ4 -

How do students from the department engage with

social media?

To address the RQs mentioned above and drawing

on the findings of the focus group study (Sousa &

Silva, 2024), we distributed a questionnaire in

February and March 2024, among a convenience

sample of current and alumni students from the

department. We sought to involve students from all

areas of study offered in the Department (i.e.

Informatics Engineering, Design and Multimedia,

and Data Science) and who were at different stages of

their academic journey, from BSc to PhD or had

recently completed their degrees. Participants

volunteered to take part and were reached through

WhatsApp groups and word of mouth.

The questionnaire was distributed through

LimeSurvey, was anonymous to ensure

confidentiality and encourage participation, and was

organised into four sections: participants'

sociodemographic data, academic journey, mentoring

programs, and digital communication preferences.

The first section included six questions and gathered

information on gender, age, academic qualifications,

current degree and year, previous degrees, current

job, and alignment of current job with their field of

study.

The second section asked whether participants'

initial expectations for their degree had been met and

about experiences of feeling lost or out of place. This

section also included questions on what would have

been useful in moments of feeling lost and out of

place, if participants had considered dropping out and

why, and to what extent participants considered

themselves informed about possible

academic/industry career trajectories.

The third section focused on mentoring programs

and gauged participants' perceptions of the benefits of

mentoring programs and their potential impact,

specifically in providing peer support, training

through workshops and round tables, and information

on key academic and career moments, either provided

though a website or through social media.

The last section sought to understand participants'

digital communication habits and asked about their

use of social media platforms, frequency of use and

purpose, and which platforms they considered more

effective for accessing mentoring programme

content.

3.3 Data Analysis

The analysis of the results followed the sections of the

questionnaire. Closed questions were analysed using

descriptive statistics, graphs and a comparative

analysis to examine responses of male participants

against female and non-binary participants, as well as

current students and alumni students. Open-ended

questions were analysed using affinity diagrams to

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

934

identify the main and recurring themes mentioned by

participants, aiming to create concise and objective

lists of topics and opinions. For the analysis, we also

compared results among genders.

The results of the questionnaires were then

analysed together with the findings of the focus group

study (Sousa & Silva, 2024) to establish a list of goals

and requirements for the digital content of the

mentoring programme and determine the specific

platform/s the contents should be featured. The list of

goals was structured according to Norman's Three

Levels of Design (Norman, 2007) and Cooper's Goal-

Directed Design (Cooper et al., 2014).

According to Norman (Norman, 2007), the human

emotional system has three interconnected levels:

visceral, behavioural, and reflective. The visceral level

involves instinctual emotions expressed automatically

and without conscious control, and that refers to users'

first impressions of a design and how they perceive a

product and the feelings it evokes. The behavioural

level related to deliberate actions, where users

unconsciously develop strategies to achieve their goals

efficiently, which is crucial for product use and the

overall user experience. Lastly, the reflective level,

which involves conscious thought, reflection, and

learning and includes users' reflections about the

product before, during, and after use.

Cooper's Goal-Directed Design framework builds

upon Norman's emotional processing levels to types of

user goals (Cooper et al., 2014) and introduces

experience goals, which relate to visceral processing

and focus on how users want to feel, emphasising

emotional responses; end goals, which are associated

with users' behaviour and refer to what users aim to

accomplish; and life goals that pertain to reflective

processing and encompass complex sentiments,

ambitions, and plans that reflect the identities users

aspire to achieve.

The list of goals, features, and platforms that we

present in section 4.2. followed the work of Norman

and Cooper to ensure that the goals met not only

functional needs but also resonated with users’

emotional levels.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Questionnaire

This section presents the results of the questionnaire.

It first describes the participants to then examine their

1

BSc. in Informatics Engineering (BIE), BSc. in Design

and Multimedia (BDM), MSc. in Informatics

academic journeys, focusing on the specific moments

when they felt lost or considered dropping out of their

degree (RQ1). Then, it looks at participants'

perspectives on the benefits and potential impact of a

mentoring programme (RQ1-2). Finally, it focuses on

the participants' digital communication habits,

identifying which social media platforms participants

use the most and for what purposes (RQ4).

4.1.1 Participants

54 current students and alumni answered the

questionnaire, 30 males (M), 23 females (F), and 1

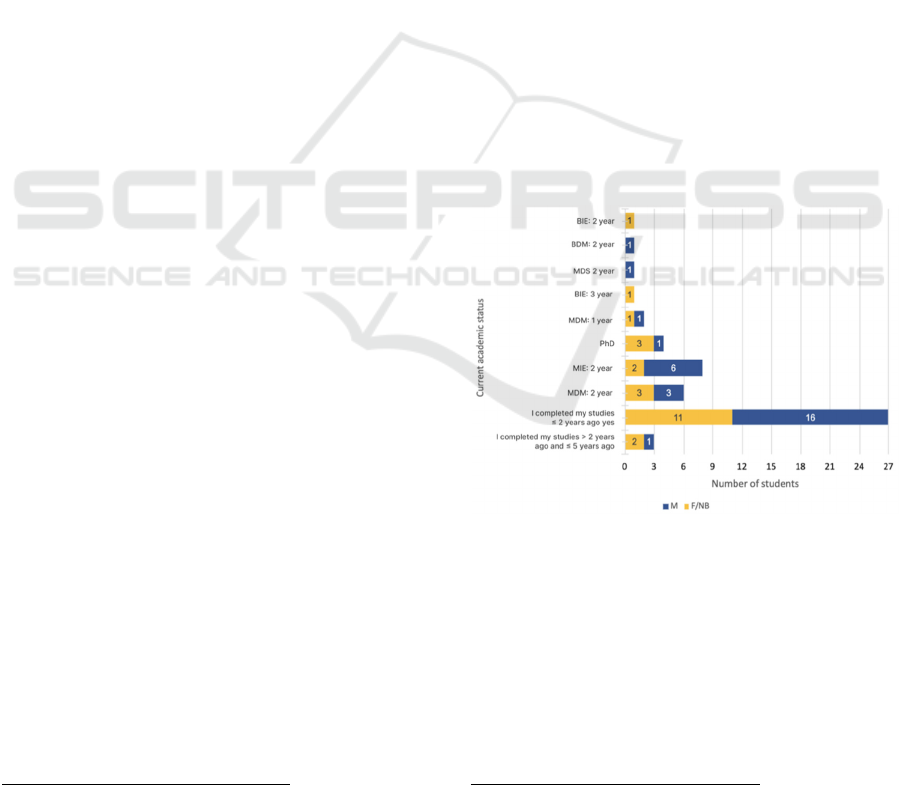

non-binary (NB) individual. As displayed on Figure

1, 24 participants were students at BSc., MSc., and

PhD. Levels, from all the degrees offered by the

department

1

, with a higher number of participants

from the design and multimedia degrees, which is

also the degree with the larger percentage of women

in the department. 30 participants were former

students of the department, with a variety of

professional positions: Full-Stack Development,

Software Development, Entrepreneurship

Management, Graphic, Digital, and Communication

Design, Product Design, Data Analysis, UX/UI

Design, Machine Learning, Software Engineering,

Consulting.

Figure 1: Participants' year of studies at the time of

answering the questionnaire.

Concerning the participants who were engaged in

academic studies, four reported pursuing a doctoral

degree (F/NB – 3; M – 1); 17 indicated that they were

enrolled in an MSc. program, eight (F/NB – 2; M – 6)

in the MSc. in Informatics Engineering, six in the in

the MSc. in Design and Multimedia (F/NB – 3; M –

3), one and data science (M – 1); and three

Engineering (MIE), MSc. in Design and Multimedia

(MDM), MSc. in Data Science (MDS).

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

935

participants were pursuing a BSc. in Informatics

Engineering (F/NB – 2) and design and multimedia

(M – 1) (Figure 1).

27 participants (F/NB – 11; M – 16) had

completed their studies in less than two years and

three (F/NB – 2; M – 1) in over two years (Figure 1).

12 (F/NB – 7; M – 5) completed BDM and MDM;

seven students (F/NB – 2; M – 5) had completed the

BEI. Four students (F/NB – 1; M – 3) completed both

BEI and MDS, and four students (F/NB – 3; M – 1)

had completed MDM. Two students (F/NB – 1; M –

1) completed the BDM. One student had completed

MDS (M), another BIE and BDM (F/NB), and

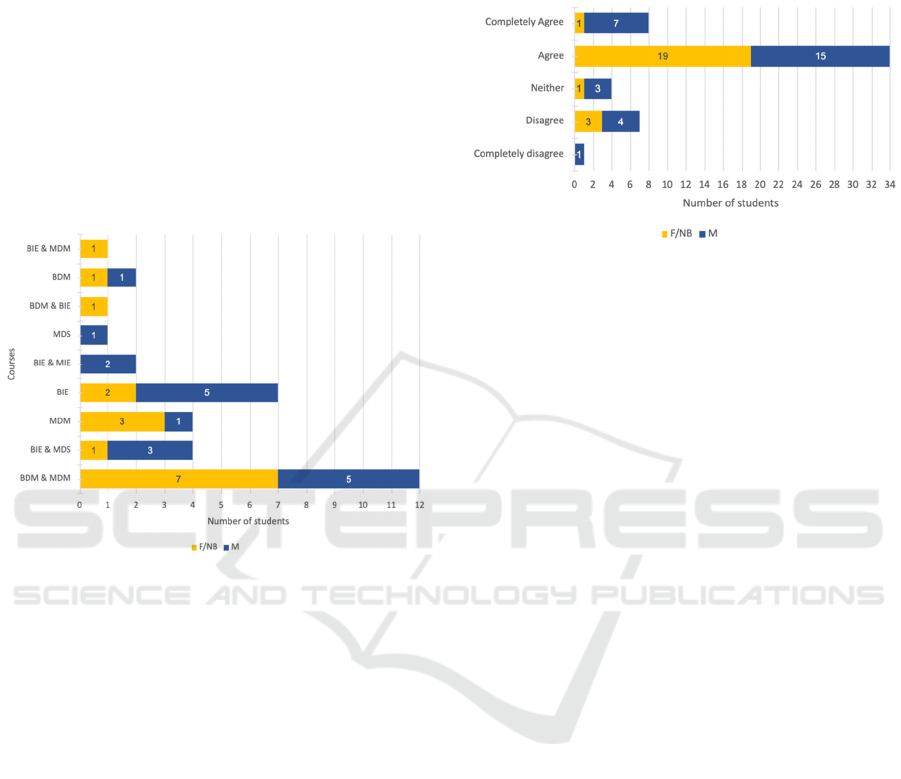

another BIE and MIE (F/NB) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Former students’ degrees.

4.1.2 Academic Journey

In response to whether their initial degree

expectations had been met, participants generally

gave positive answers (Figure 3). Out of 54

responses, 20 participants identifying as female or

non-binary and 22 male participants agreed that their

expectations were met.

29 male students and 24 female or non-binary

students reported feeling lost or out of place during

their academic journeys. The multiple-choice

question highlighted key challenges they faced, such

as difficulty deciding what to do after a bachelor's

degree (F/NB – 16; M – 12), navigating job

applications (F/NB – 14; M – 14), choosing a field for

a master's (F/NB – 9; M – 15), creating a CV or

LinkedIn profile (F/NB – 13; M – 10), a lack of

guidance on career paths (F/NB – 10; M – 8),

deciding whether to pursue a PhD (F/NB – 6; M – 6),

understanding PhD programs (F/NB – 3; M – 3), and

managing PhD application processes (F/NB – 2; M –

1). When asked for any additional challenges or

moments of feeling lost, four participants expressed

concerns about time management skills, difficulty

choosing a topic for their MSc. dissertations, and

difficulty deciding what to do after finishing high

school.

Figure 3: Degree expectations.

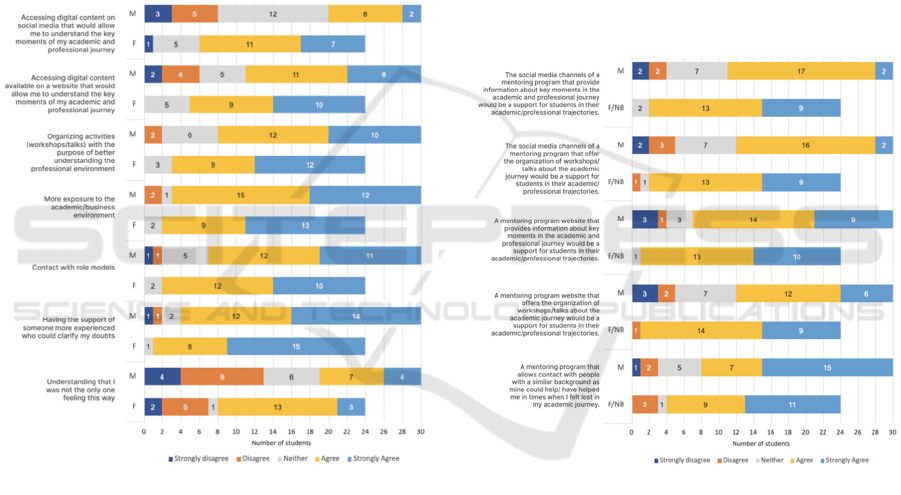

In examining factors that could have supported

students during difficult moments, participants

expressed a lack of consensus on the notion of

"realising they were not alone" (F/NB - 16 positive 7

negative, M – 11 positive 13 negative), but there was

general agreement that activities offered by a

mentoring programme would have been beneficial, as

shown in Figure 4. Female and non-binary students

were more positive about using digital resources to

navigate key moments (1 negative response), and

male students were less inclined to find them helpful

(14 negative responses). When asked to suggest

additional factors that could have been helpful at

moments of feeling lost, participants said it would

have been good to:

• Gain Work Experience: Encourage students to

pursue work experience after their

undergraduate studies to explore the various

areas within Informatics more deeply.

• Get Exposure at High School: Increase

awareness among high school students about

higher education and the diverse career

opportunities available.

• Integrate Internship Programs: Incorporate

internship programs into both undergraduate

and master’s degree curricula to provide

students with practical experience.

• Offer Short-Term Internships: Provide

opportunities for short-term internships, such

as summer programs, to supplement academic

learning.

• Meet Diverse Role Models: Emphasise the

importance of diverse role models in design

fields such as graphic design and animation,

rather than solely in technological areas, to

inspire students.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

936

• Organise Career-oriented Workshops:

Organise workshops focused on portfolio

development and strategies for effectively

submitting portfolios to companies and

universities.

• Implement Mentoring Programs: Establish

mentoring programs to offer career guidance

and support in CVs that align with individual

interests.

When participants were asked if they felt

informed about potential career paths in academia and

industry, as well as the steps needed to pursue those

paths, 12 women and non-binary individuals

expressed disagreement or uncertainty. This indicates

a lack of clarity about these options and emphasizes

the need for more exploration and support in this area.

Figure 4: Factors that could have supported students.

4.1.3 Potential Impact of a Mentoring

Program

Participants were asked whether a mentoring

programme that facilitated contact with individuals

with a similar background would have helped during

moments of feeling lost in the academic journey and

whether the website or the social media presence of a

mentoring programme featuring workshops, talks,

and information on key academic and professional

moments would have helped provide support in their

academic and professional journeys? (RQ3) While 12

male participants expressed indifference about these

activities and their benefits, those identifying as

women and non-binary individuals acknowledged the

value of the activities organised by the program

(Figure 5).

4.1.4 Digital Communication

Answers about participants digital communication

habits show that Instagram and WhatsApp are the

most frequently used social media platforms among

respondents, with participants accessing them more

than twice a day (Instagram: F/NB – 22; M – 20;

WhatsApp: F/NB – 18; M – 21). Instagram is

primarily used for staying informed about news,

chatting with friends, enjoying art and recipes,

engaging with thematic content, finding

entertainment, seeking inspiration, sharing work, and

professional networking. WhatsApp is used for

personal and professional communication, chatting

with family and friends, organising events, and taking

part in group discussions.

Figure 5: Benefits of a mentoring programme.

Regarding the most effective social media

platforms for accessing mentoring programme

content, participants most frequently chose Instagram

(F/NB – 13; M – 7), followed by the program's

website (F/NB – 7; M – 10), LinkedIn (F/NB – 2; M

– 6), YouTube (F/NB – 0; M – 4), and WhatsApp

(F/NB – 2; M – 2). When asked to suggest effective

methods for accessing content from a mentoring

program, 4 participants proposed traditional methods

such as posters and physical flyers; LinkedIn to

discover content and establish connections; public

spaces or incorporating programme promotion into

academic settings; and leveraging platforms like

TikTok and Spotify. Additionally, participants

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

937

recommended newsletters and FAQs or forums to

facilitate ongoing engagement and support.

Regarding the types of content that could be

featured on the mentoring program's website, to

support all students in the department, regardless of

gender (RQ3), participants said it would be valuable

to provide information on how to apply for the

mentoring programme (F/NB – 21; M – 25); how to

connect with role models (F/NB – 21; M – 18); video

testimonials (F/NB – 18; M – 19); FAQs about

academic and career paths (F/NB – 24; M – 27); and

templates for CVs and LinkedIn profiles (F/NB – 19;

M – 27) (Figure 6). Additionally, 6 participants

provided suggestions for content that they would

expect to find on a mentoring programme website:

• Activities within the programme itself,

• Mentors’ biography and background;

• Topics to explore related to career

advancement;

• Discussions of whether to continue their

studies or directly enter the job market;

• Guidance on job search platforms and

interview techniques;

• Informative content, such as videos or posts

featuring real-life experiences; and

• Advice on building a strong and balanced

portfolio.

4.2 Digital Content and User Goals for

Mentoring Programmes

By iteratively connecting and analysing the findings

from the focus group (Sousa & Silva, 2024) and the

questionnaire responses, we developed a structured

list of requirements that prioritise user needs for the

online presence of the INSPIRA mentoring

programme (Table I). The list of goals was organised

according to Norman’s visceral, behavioural, and

reflective levels (Norman, 2007) and Cooper's

experience, end, and life goals. In design, Norman’s

levels and Cooper’s goals combine to shape the

overall product experience, influencing users'

perceptions, interactions, and thoughts about the

product (Cooper et al., 2014). Requirements

concerning how the user wants to feel, e.g., connected

with role models, were classified under Experience

goals. Requirements about what the user wants to do,

e.g., learn how to structure a CV were classified as

Behavioural goals. Requirements regarding who a

user wants to be, e.g., a better time manager, were

classified as Reflective goals.

For each user goal, Table I indicates whether that

goal was derived from the previous focus group study

[FG] or the finding of the questionnaires developed in

this study [Q]. Because Instagram and the program’s

website emerged as the preferred platforms among

participants, these are the channels included in table

of user goals to illustrate how the goals can be

operationalised.

Figure 6: Content for a mentoring program website.

Table I, the first and second columns, lists the

goals the mentoring program digital channels can

address. The third column maps user goals and

associated content to the website's pages and the

features required for their implementation. The last

column outlines the types of social media posts that

align with each user goal and how to address these on

social media. Some user goals are presented on both

the website and Instagram posts to keep consistent

and clear messaging across the program's platforms,

which may help boost engagement and satisfaction

within the target audience.

5 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This study investigated the challenges faced by

students from an Informatics department throughout

their academic journeys and the types of content that

could support them. It also sought to understand

participants' social media preferences to determine

the most suitable digital platforms to make content

available. The findings of this study culminated in a

set of tailored digital content and user goals for the

digital platforms of INSPIRA, a mentoring

programme for women in Informatics. In doing so,

this study not only identified what types of content

are helpful for a mentoring program for women in

Informatics but also outlined a possible

methodological approach for identifying user-goal-

oriented content.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

938

Table 1: Website features and social media posts based on the user goals.

User Goals Website Pa

g

e and Features Social Media Posts

Visceral

Design

(Experience

Goals)

Connect with knowledgeable individuals/role

models with diverse backgrounds [FG; Q]

Homepage & Activities page - Videos/ Text-

based content with testimonials & Calendar

event

Videos/ Text-based

content with testimonials

Understand Erasmus process and new

partnership establishment between universities

[FG]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Find inspiration in the Department environment,

as a designer [FG; Q]

Activities page - Calendar Event

Instagram posts redirecting

to other pages/activities

within the Department

Gain awareness of the Department's degrees and

its procedures [FG]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Have a sense of belonging in a new and

predominantly male-dominated environment

[Q]

Activities page - Calendar Event —

Understand the criteria for choosing optional

courses in the MSc. degree [FG]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Understand the masters’ dissertation process and

advisor selection [FG; Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Understand what a doctoral degree is, its

requirements and advisor selection [FG; Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Understand how to choose a doctoral degree

p

roposal [FG]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Understand procedures for entering the Job

Market or Academic world [FG; Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

Instagram posts with

tips/testimonials &

redirecting to other pages

Relate to common questions of students [FG]

FAQs page - Form to collect student’s

questions and allow subsequent analysis

—

Behavioural

Design

(End Goals)

Learn to structure a CV/portfolio [FG; Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

Instagram posts with tips

& redirecting to other

p

ages

Access a visually appealing website tailored to

students’ needs [FG; Q]

—

Instagram posts with tips

& testimonials

Be able to choose a master's programme by

having clear guidance [FG; Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Discover the repository of old theses [FG]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

—

Learn about job search platforms and interview

techniques [Q]

FAQs page - Drop down with text-based

content & Redirecting to external sources

Instagram posts with

tips/testimonials &

redirecting to other pages

Access INSPIRA Mentor Information [Q]

M

entors page -Text-

b

ased content

—

Access informative content on real-life

experiences [Q]

Homepage - Videos and Instagram posts

with testimonials

Videos & text-based

content with testimonials

Access INSPIRA activities [Q]

A

ctivities page - Calendar event

—

Reflective

Design

(Life Goals)

Enhance time management skills [Q] —

Instagram posts with tips

& testimonials redirecting

to other pages

Learn about the possible career paths [FG; Q] Activities page - Calendar event

Instagram posts with tips

& testimonials

Decide between the Job Market or the Academic

world [FG; Q]

—

Videos/ Text-based

content with testimonials

Our previous focus group study (Sousa & Silva,

2024) suggested that a mentoring program could

support participants by offering mentorship, peer

support, tailored digital content for websites and

social media, and assistance during specific

challenges. This study complements those findings,

revealing that male students also experience

challenges. Additionally, this study indicates that

students' key challenges are linked to the need for

more guidance on career paths, job applications, and

post-degree decisions.

Additionally, the study contributes to our

understanding of the solutions that female, non-

binary, and male participants believe can be helpful

and how a mentoring program could support

addressing those needs. It also highlights the type of

digital content that would be most effective for the

program's online presence and which social media

platforms to focus on based on the participants'

preferences of use. Our findings indicate the need for

a combination of social, educational and career

support, confirming the need for structured

mentorship with guidance on both professional skills

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

939

and personal development, as highlighted by e.g.

(Singh & Basu, 2021) (Aufschläger et al., 2023).

Similarly to Singh and Basu (2021), our study

highlights that building a community – in this study,

on platforms like Instagram and LinkedIn – could

foster a sense of inclusion and belonging. Moreover,

our findings underscore the importance of digital

media and the creation of an online community where

participants feel informed and connected. Based on

participants’ responses, future programmes might

explore additional online platforms to maximize

engagement in mentoring initiatives.

Our findings align with and expand on the

recommendations made by Paukstadt et al. (2018).

Participants in our study also showed a strong interest

in role models and content reflecting real-world

experiences. Additionally, this research's insights

highlight the interest in making available CV

templates and FAQs.

This study does have limitations. Responses were

from current and alumni students and having more

responses and perspectives from current students

could have enriched the results. However, despite

their recent graduation, these former students

provided insights into their complete academic

experiences. Furthermore, we were looking to find

challenges experienced across their degrees, so

alumni’s insights were as appropriate as those from

current students, except for problems that could have

possibly been recently resolved.

Male participants tended to exhibit a neutral

stance on the activities of mentoring programs and

their benefits. Conversely, women and non-binary

individuals acknowledged the helpfulness of a

mentoring programme and the importance of its

online presence through its website and social media.

That male participants had less favourable opinions is

not surprising as the mentoring programme is targeted

at women and that could have impacted their points

of views. This also can suggest that gender may

influence perceptions on mentoring, opening a gap

for further research to close by researching how

mentoring programmes can further be adapted to

overcome these gender-based barriers. Because this

study focuses on participants from one single

Informatics department limits the generalisability of

the results to other departments. This relates to the

preliminary nature of the study, nonetheless, other

departments could adopt the approach we followed to

identify the specific needs of their departments

namely by running focus groups, distributing

questionnaires, and organising their results into goals

and design website features and social media content

that align with the objectives of their mentoring

programs. Although this study does not include

statistics on the gender gap in IT outside of Europe,

we present studies from the U.S. that emphasize that

this is a global issue. Singh and Basu (2021) focus on

initiatives to reduce the gender gap in tech, while

Boyer et al. (2010) explore strategies to improve

retention rates among computing majors by

strengthening students' computing identities. The fact

that such studies are being conducted in the U.S.

highlights the significance of this issue. Therefore,

departments beyond Portugal and Europe could also

benefit from adopting the framework we propose.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Mentoring programs and their online platforms can be

valuable tools to support students, researchers, and

academics in Informatics. This study examines how

the content of the mentoring program's platforms can

be a support for the students of an Informatics

department, as well as the social media the

programme should focus on based on the student's

social media engagement and their preferences

regarding primary communication and information

channels. The themes that constitute that content, are

knowledge shared by experienced individuals and

role models in the ICT area; information on degrees

and procedures within the Department of Informatics

Engineering; common questions asked by the student

community in the department; career path options;

recruitment procedures, including documents such as

CVs and portfolios; tips on how to foster a sense of

belonging in a male-dominated field.

This study contributes to existing knowledge on

mentoring programs in Informatics by presenting a

research methodology framework that other

programs can use to enhance their support for specific

student communities. It provides a list of user goals

for mentoring programme platforms and outlines how

each goal can be effectively addressed, either through

a website or social media. Additionally, the study

contributes to the development of initiatives designed

to reduce gender disparities in Informatics through

mentoring programs, such as INSPIRA, to establish a

more inclusive support system for women in

Informatics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the students of the

Informatics department who participated in this study

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

940

for sharing their insights and time with INSPIRA.

This work is financed through national funds by FCT

- Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., in the

framework of the Project UIDB/00326/2025 and

UIDP/00326/2025.

REFERENCES

Aufschläger, L. T., Kusanke, K., Witte, A. K., Kendziorra,

J., & Winkler, T. J. (2023). Women Mentoring

Programs to Reduce the Gender Gap in IT Professions

A Literature Review and Critical Reflection. In

AMCIS.

Blumberg, S., Krawina, M., Mäkelä, E., & Soller, H. (2023,

January 24). Women in tech in Europe | McKinsey.

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digi

tal/our-insights/women-in-tech-the-best-bet-to-solve-e

uropes-talent-shortage

Boyer, K. E., Thomas, E. N., Rorrer, A. S., Cooper, D., &

Vouk, M. A. (2010). Increasing technical excellence,

leadership and commitment of computing students

through identity-based mentoring, proceedings of the

41st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science

Education. Milwaukee, 10, 1734263-1734320.

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D., & Noessel, C. (2014).

About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design. John

Wiley & Sons.

De Luca, S. (2023). Women in the digital sector.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATA

G/2023/739380/EPRS_ATA(2023)739380_EN.pdf

Eurostat (a) - Statistics Explained (2024). European

Commission. ICT specialists in employment.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.

php?title=ICT_specialists_in_employment

Eurostat (b) - Statistics Explained (2024). European

Commission. ICT education - a statistical overview.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.

php?title=ICT_education_-_a_statistical_overview

Frieze, C., & Quesenberry, J. (2015). Kicking Butt in

Computer Science: Women in Computing at Carnegie

Mellon University, Nov. 12, 2015.

Funk, C., & Parker, K. (2018) Women and Men in STEM

Often at Odds Over Workplace Equity. [Report]. Pew

Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social

trends/2018/01/09/women-and-men-in-stem-often-at-

odds-over-workplace-equity/

Happe, L., Buhnova, B., Koziolek, A., & Wagner, I. (2021).

Effective measures to foster girls’ interest in secondary

computer science education. Education and

Information Technologies, 26(3), 2811–2829.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10379-x

Meschitti, Viviana and Helen Lawton Smith (2017). “Does

Mentoring Make a Difference for Women Academics?

Evidence from the Literature and a Guide for Future

Research”. In: Journal of Research in Gender Studies

7.1, pp. 166–199 doi: 10.22381/JRGS712017

Norman, D. (2007). Emotional Design: Why We Love (or

Hate) Everyday Things. Hachette UK.

Paukstadt, U., Bergener, K., Becker, J., Dahl, V., Denz, C.,

& Zeisberg, I. (2018). Design Recommendations for

Web-based Career Guidance Platforms—Let Young

Women Experience IT Careers! Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences 2018 (HICSS-51).

https://aisel.aisnet.org/hicss-51/os/socio-technical_issu

es_in_it/4

Petean, R., & Rincon, R. (2024, June). Navigating the

Personal and Professional: How University STEM

Mentorship Programs Support Women in Austria and

Germany. In 2024 ASEE Annual Conference &

Exposition.

Singh, S., & Basu, D. (2021). Impact on women

undergraduate CS students' experiences from a

mentoring program. In Proceedings of the 52nd ACM

Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education

(pp. 1266-1266).

Sousa, F., & Silva, P. A. (2024). Digital media content for

mentoring programs targeted at women in informatics.

Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on

Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL 2024).

Webb, M. (2023, July 11). 60+ Women in Tech Statistics

You Need to Know in 2024: Trends, Gaps, and

Challenges. Techopedia. https://www.techopedia.com/

women-in-tech-statistics

Widdicks, K., Ashcroft, A., Winter, E., & Blair, L. (2021).

Women’s Sense of Belonging in Computer Science

Education: The Need for a Collective Response.

Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on United

Kingdom & Ireland Computing Education Research, 1–

7. https://doi.org/10.1145/3481282.3481288

Shaping the Digital Content of Mentoring Programs for Women in Informatics: Insights from an Exploratory Study

941