T-Shaped Competencies in Academic and IT Service Synergies

Zuzana Schwarzov

´

a, Leonard Walletzk

´

y, Patrik Proch

´

azka, Kl

´

ara Kub

´

ı

ˇ

ckov

´

a and Janka Marschalkov

´

a

Faculty of Informatics, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

{433529, 133, 418277, 492710, 493097}@muni.cz

Keywords:

T-Shaped Professional, Education Models, Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary.

Abstract:

In the 21st century, education and business face increasingly complex challenges that require multidisciplinary

approaches. This paper explores the concept of T-shaped competencies, which combine deep knowledge in

one domain with a broad range of skills across other areas. By examining case studies from both academia and

business, the paper highlights the importance of multidisciplinary education and collaboration in fostering in-

novation and competitive advantage. The findings emphasize the need for continuous adaptation of knowledge

and skills, as well as the potential impact of AI tools on multidisciplinary competencies. The paper concludes

that a synergistic relationship between academia and business is essential for addressing complex problems

and driving value co-creation.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the 21st century, education faces increasingly com-

plex problems that cannot be addressed by a single

discipline alone. The traditional approach of focus-

ing on one area of expertise is no longer sufficient to

tackle the multifaceted challenges of today’s world.

As highlighted by Kunze, Stadler, and Greiff (Kunze

et al., 2023), complex problem-solving is a crucial

skill for the 21st century, requiring a multidisciplinary

approach to education. Multidisciplinary teams have

become essential for success in service design. These

teams bring together diverse expertise, enabling inno-

vative solutions and fostering service innovation. Ac-

cording to Joly et al. (Joly et al., 2019), leveraging a

multidisciplinary approach in service design is key to

creating new forms of value co-creation.

However, achieving a common understanding

within such teams remains a core challenge. The solu-

tion lies in multidisciplinary education, which equips

individuals with the skills to collaborate effectively

across different fields. This approach is equally ap-

plicable to academic research, where interdisciplinary

collaboration can lead to groundbreaking discoveries.

In the business world, service provision increas-

ingly relies on multidisciplinary knowledge. Under-

standing how this approach is perceived and imple-

mented in business is crucial for fostering innovation

and competitiveness. Mirafzal et al. (Mirafzal et al.,

2023) emphasize the importance of knowledge man-

agement in multidisciplinary service design organiza-

tions, highlighting the role of diverse expertise in im-

proving performance. Spohrer and Maglio (Spohrer

et al., 2007) also discuss the importance of service

systems and the role of multidisciplinary teams in

driving innovation and value co-creation.

The aim of this paper is to present both academic

and business perspectives on multidisciplinary ap-

proaches. By showcasing case studies from both do-

mains, we aim to illustrate the benefits and challenges

of fostering multidisciplinary competencies in educa-

tion, research, and business.

2 MULTIDISCIPLINARY AND

INTERDISCIPLINARY

The terms ”multidisciplinary” and ”interdisciplinary”

have distinct meanings. Multidisciplinary approaches

involve multiple disciplines working together on a

common project, each retaining its methodologies

and perspectives. For example, a healthcare team

might include doctors, nurses, and social workers,

each contributing their expertise without blending

methods.

In contrast, interdisciplinary approaches integrate

knowledge and methods from different disciplines to

create a unified approach. For instance, an interdis-

ciplinary research project might combine psychology,

sociology, and neuroscience to study human behavior,

with researchers actively integrating their approaches.

Schwarzová, Z., Walletzký, L., Procházka, P., Kubí

ˇ

cková, K. and Marschalková, J.

T-Shaped Competencies in Academic and IT Service Synergies.

DOI: 10.5220/0013288400003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 729-736

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

729

In summary, multidisciplinary work involves par-

allel contributions from different disciplines, while

interdisciplinary work integrates knowledge and

methods to create a cohesive approach. Both have

their merits, with interdisciplinary work often seen as

more effective for complex problems, while multidis-

ciplinary work offers flexibility.

3 TYPES OF KNOWLEDGE

STRUCTURES

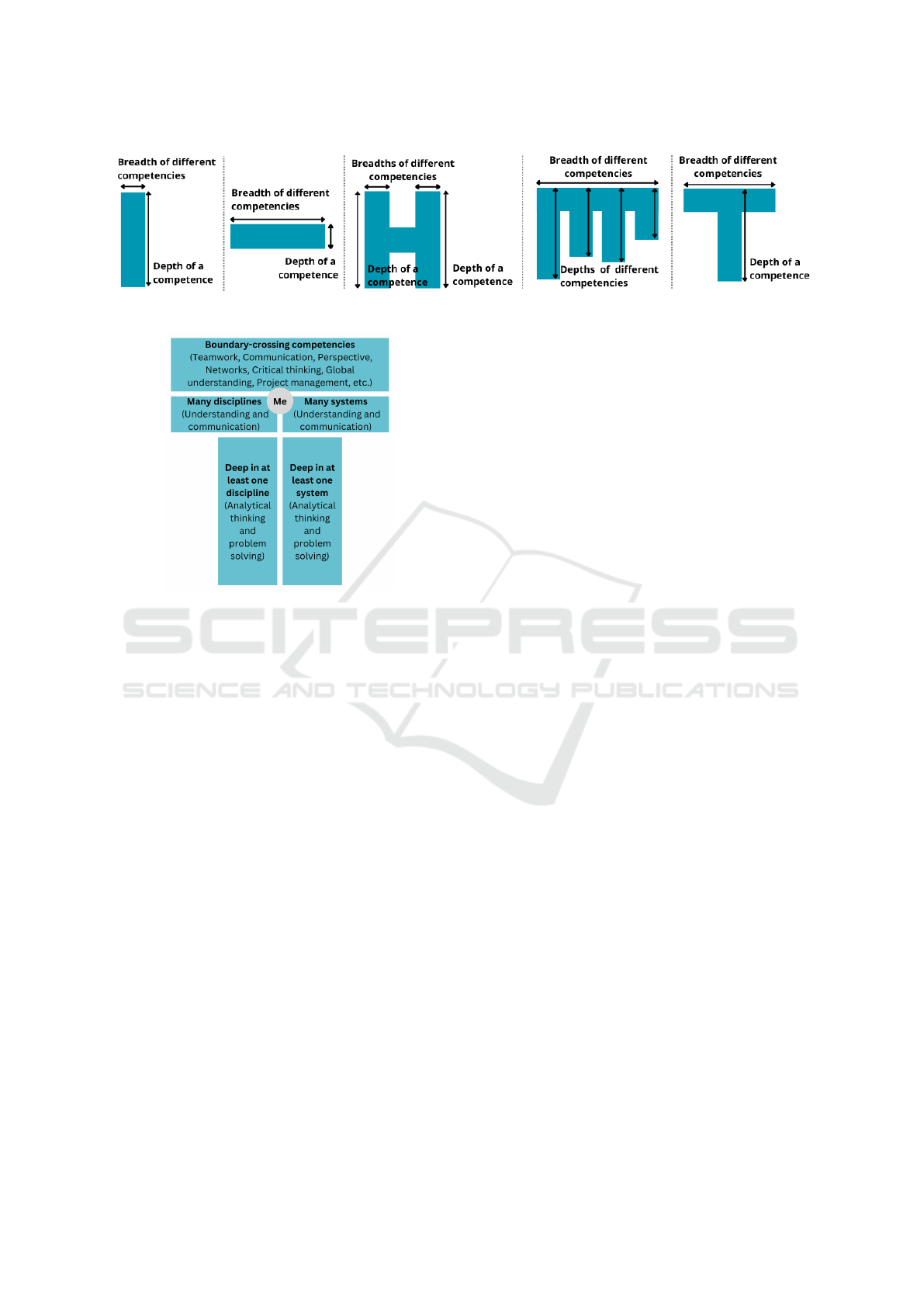

Professionals can be categorized into knowledge

structures based on depth and breadth of their com-

petencies, skills and knowledge. These knowledge

structures, or knowledge profiles, are represented by

different shapes (Fig. 1) with the most common be-

ing I-shaped, Dash-shaped, H-shaped, M-shaped and

T-shaped profiles (Demirkan and Spohrer, 2015):

• I-shaped: professionals possess deep knowledge

in one domain, excelling in their field but often

lacking interdisciplinary cooperation and commu-

nication (Saukkonen and Kreus, 2022), which can

be a disadvantage in modern challenges (Bierema,

2019).

• Dash-shaped: individuals, represented by a hor-

izontal line, have broad competencies across do-

mains but lack deep expertise, which benefits in-

terdisciplinary collaborations (Ninan et al., 2022).

• H-shaped: professionals have deep knowledge

in two domains, represented by two vertical lines

connected by a horizontal line, symbolizing their

ability to integrate both of these areas into their

professional work (Saukkonen and Kreus, 2022).

Their dual expertise limits expansion into other

domains (Ninan et al., 2022).

• M-shaped (comb-shaped): individuals have ex-

pertise in multiple domains, represented by mul-

tiple vertical lines, though their knowledge is less

in-depth compared to I-shaped or H-shaped pro-

fessionals (Ninan et al., 2022).

• T-shaped: professionals combine the strengths

of dash-shaped and I-shaped profiles, with deep

knowledge in one domain and interdisciplinary

overlaps into secondary domains (Ninan et al.,

2022).

4 T-SHAPED PROFILE

The term ’T-shape’ can be traced back to 1991, when

Guest (Guest, 1991) described the need for a ’renais-

sance man’, that would combine IT skills with busi-

ness expertise (Conley et al., 2017). Amber (Amber,

2000) expanded this idea, calling for T-shaped indi-

viduals with deep expertise in one area and the abil-

ity to extend into unknown fields, enabling them to

solve multidisciplinary problems. Tim Brown, CEO

of IDEO, later popularized the term (Brown, 2010).

The detailed design for this knowledge profile has

been adjusted by multiple researchers (Barile et al.,

2014; Saviano et al., 2016; Gardner, 2017; Saukko-

nen and Kreus, 2022), leading to a mostly unified de-

sign presented in Figure 2. The skills in the horizon-

tal part of the T can depend on interpretation, how-

ever they usually enable the person to collaborate with

professional from another domain without difficulties.

These skills can include project management, com-

munication and soft skills, creative thinking, team-

work, and they can be also from other scientific or

engineering disciplines, such as statistics, economics,

arts, etc. However, the breadth of these skills does not

match the depth of expertise found in the vertical bar

(Kruusmaa, 2017).

4.1 Academia Perspective

Social and economic changes, like globalization, have

led to specialized roles and educational paths. While

specialized knowledge addresses specific problems,

these models struggle with modern challenges due

to overlapping dimensions and rapid changes (Sa-

viano et al., 2016). Educating students with a mul-

tidisciplinary focus is key for future organizations.

However, the current educational system still empha-

sizes single-domain expertise, creating I-shaped pro-

fessionals (Demirkan and Spohrer, 2018).

4.1.1 Adapting T-Shape into Curriculum

The research results of universities introducing T-

shape into their educational curriculum show that be-

ing a T-shaped professional can prove beneficial in

various domains.

The University of Southern California identified

weaknesses in their I-shaped software engineering

master’s students, recognizing the need for multidis-

ciplinary thinking. They adapted their courses to sup-

port the development of T-shaped professionals by

having students work on real-life service development

projects, engaging with the entire service design pro-

cess from client negotiation to maintenance planning

(Boehm and Mobasser, 2015).

Tallinn University of Technology highlights the

need for T-shaped professionals in the mining sector,

emphasizing the importance of developing these skills

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

730

Figure 1: I-Shaped, Dash-shaped, H-shaped, M-shaped and T-shaped profiles. Adapted from: (Ninan et al., 2022).

Figure 2: Detailed design of the T-shaped knowledge archi-

tecture. Redrawn from: (Freund et al., 2024).

in master’s students and creating suitable work envi-

ronments to retain them (Robam et al., 2023).

The use of interactive models based on real data

has been shown to enhance T-shaped skills in hydrol-

ogy students at a US community college. Students

using real data in seminars demonstrated a better un-

derstanding of the hydrological domain, the role of

hydrology specialists, and the field’s impact on so-

ciety (Sanchez et al., 2016). Similarly, the Institute

for Water Education in Delft, Netherlands, proposed

incorporating T-shaped learning into their master’s

programs to foster effective teamwork. This would

involve students working on real-world problems in

various roles, including fieldwork and discussions

with professionals, with assessments designed to fur-

ther enhance different competencies (Uhlenbrook and

Jong, 2012).

The presented cases on modifying university cur-

ricula to foster T-shaped graduates highlight the im-

portance of integrating real-world examples into aca-

demic experiences. Collaborations between students

and industry partners extend professional roles be-

yond domain-specific expertise, aiding in the cultiva-

tion of essential skills for addressing complex, multi-

disciplinary problems. Exposure to real-world prob-

lems enhances students’ capacity to manage com-

plexity and contradiction, fostering leadership skills

(Tranquillo, 2017).

4.1.2 T-Shaped Researchers

The examples of adapting the universities’ educa-

tional practices can lead to a conclusion that by fos-

tering T-shaped skills at the undergraduate levels, the

doctoral students and academic researchers in the fu-

ture will be not only experts in their domain but pro-

ficient multidisciplinary collaborators as well. How-

ever, there is a gap in researching the T-shaped skills

in academic research and a further exploration is still

needed (Walletzk

´

y et al., 2024).

4.2 Business Perspective

In the business context, T-shaped professionals are

valued for their ability to drive innovation and en-

hance organizational resilience by combining deep

expertise in a core domain with broad, adaptable

knowledge. Their effective collaboration across busi-

ness functions fosters a responsive environment that

aligns with changing market demands and supports

long-term competitiveness.

4.2.1 The Role of T-Shaped Professionals in

Business Transformation

One of the most compelling applications of T-shaped

professionals is within digital and/or AI transforma-

tion, balancing specialized technical skills with ef-

fective communication across teams and disciplines

(Demirkan and Spohrer, 2018). They excel in envi-

ronments requiring flexibility, critical thinking, and

lifelong learning, crucial for adapting to technologi-

cal advancements (Bierema, 2019).

By facilitating a holistic view of customer ex-

periences, T-shaped professionals enable organiza-

tions to move beyond product innovation towards in-

tegrated service solutions, where technology is an en-

abler rather than the focus. The shift towards a ser-

vice focus requires changes in mindsets and behav-

iors. T-shaped professionals facilitate this by adopt-

ing an integrated perspective, moving organizations

T-Shaped Competencies in Academic and IT Service Synergies

731

beyond product innovation to innovative service so-

lutions that cater to customer and stakeholder needs

(Demirkan and Spohrer, 2015).

In essence, T-shaped professionals provide the

adaptable, interdisciplinary skills that are essential for

navigating the complexities of service-oriented inno-

vation. Their ability to integrate technical proficiency

with a deep understanding of human-centered needs

empowers organizations to create more meaningful,

sustainable solutions that align with evolving cus-

tomer and market demands. T-shaped professionals

contribute to dynamic capabilities by bringing cross-

functional knowledge and collaborative skills, vital

for sustaining competitive advantage (Barile et al.,

2014). Their effective communication supports in-

terorganizational learning, enabling businesses to de-

velop new strategies and adapt to emerging trends

(Saviano and Barile, 2013).

For example, in fields requiring project manage-

ment and cross-functional teamwork, such as in-

frastructure development, the versatility of T-shaped

professionals is particularly valuable. Infrastructure

projects often face technical, social, and political

complexities that demand both in-depth knowledge

and a broad understanding of various stakeholder

needs (Ninan et al., 2022). T-shaped professionals,

with their combined depth and breadth of expertise,

can manage these complexities more effectively, co-

ordinating between technical and non-technical teams

to ensure project success (Ninan et al., 2022).

5 SELECTED CASE STUDIES

Our team has initiated the research into the role and

perception of T-shape in the IT domain, starting with

exploring the IT academic research and IT businesses.

We are conducting case studies in universities and

companies located in Brno, Czech Republic. Our goal

is to address the importance of T-shaped skills in these

two domains and investigate its role in their mutual

collaboration, knowledge and innovation sharing. We

have results from one university and one company to

date, which are presented in the following sections.

Research in other institutions is still ongoing.

5.1 T-Shape in Academia

The first case study (Walletzk

´

y et al., 2024) focused

on the role of T-shaped knowledge in IT academic

research, specifically at the Faculty of Informatics,

Masaryk University. A questionnaire survey targeting

research groups and laboratories was conducted to as-

sess how this concept is perceived by their members

— researchers and students alike.

5.1.1 Methodology

The case study data was collected through an on-

line, anonymous survey sent to research group leaders

at Masaryk University’s Faculty of Informatics, who

shared it with researchers and students. The survey

included both closed and open questions, with open

questions allowing respondents to elaborate. Partic-

ipation was voluntary, except for an initial question

gauging familiarity with the ”T-shaped” concept. The

survey focused on three main areas: characterizing

respondents’ skills and research focus, assessing their

proactive learning efforts outside their primary field,

and evaluating perceptions of T-shaped learning in

academia.

5.1.2 Results and Analysis

Survey was completed by 24 respondents from var-

ious research groups. The results showed that more

than half of the respondents engage in applied re-

search and more than 60 % identify themselves as

interdisciplinary researchers, combining knowledge

from multiple fields. Key skills outside their pri-

mary specialization included academic writing, social

skills, and project management, highlighting the need

for effective communication and teamwork in inter-

disciplinary settings.

A majority of respondents (over 75 %) actively

pursued knowledge beyond their primary field, de-

spite challenges such as time limitations and resource

availability. Strategies included engaging with ex-

perts, attending conferences, and self-study through

journals and online learning platforms, showcasing a

strong commitment to broadening their skill sets.

The perceived value of T-shaped knowledge was

particularly notable in research, where 100 % of re-

spondents found it beneficial, with majority marking

it as ”very useful”. It was also highly valued in study-

ing, though perceived slightly less useful in teach-

ing, where neutral responses reflected its varied rel-

evance among those not involved in teaching roles.

Respondents cited benefits such as enhanced com-

munication at conferences, enriched research through

cross-disciplinary insights, and improved adaptability

in teaching.

Overall, this initial case study presented the im-

portance of T-shaped knowledge in academic research

and its contribution to effective collaboration and in-

novation.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

732

5.2 T-Shape in Business

The second case study explores how T-shaped com-

petencies manifest in a business context by examining

the environment of a specific IT company. This study

focuses on a leading Enterprise Resource Planning

(ERP) provider, where the importance of T-shaped

professionals in integrating technical expertise with

business acumen is highlighted. Their ERP software

includes programs for all core business areas, such

as procurement, production, materials management,

sales, marketing, finance, and human resources. This

company develops standard software for business so-

lutions and continues to offer industry-leading ERP

solutions.

The case study was carried out in one specific lo-

cation, which is a part of a chain of research and de-

velopment entities. Since this location focuses on so-

lutions dealing with finance, sustainability, and busi-

ness intelligence and development, the employees

who participated in this case study come from this

specific background. The case study gathers both

quantitative and qualitative data to look for possible

trends and patterns as well as to better understand why

and how they might arise.

5.2.1 Methodology

The data for the case study were firstly gathered by an

on-line anonymous survey. During this survey, em-

ployees were asked both open and closed questions,

which focused on the T-shape concept. The survey

was divided into multiple sections. At the beginning,

we ensured that respondents were familiarized with

the concept of T-shape.

The first section then focused on the details of

their job, namely on the role in the company, the

amount of experience they have, the learning and mul-

tidisciplinarity their job requires and the distribution

and shape of their knowledge and skills.

The following section dealt with the educational

background of the participants and its allignment with

their current role. They were also asked about the

usefulness of different educational approaches in their

primary and secondary disciplines.

The last section focused on learning opportunities,

exploring how encouraged they feel to widen their

knowledge and focusing on their experiences when it

comes to interdisciplinary learning.

Additionally, research among hiring managers is

being conducted to better understand the current and

future role of T-shape and interdisciplinarity. This

research consists of a modified questionnaire and

follow-up interviews, which could provide qualitative

data and further insight into the concept. As this re-

search is still ongoing, no results are available yet.

5.2.2 Results and Analysis

The survey has gained 65 respondents, who came

from a diverse range of roles within the company.

Most of them occupied a technical position, char-

acterizing themselves as developers, however, other

roles such as product owners and quality assurance

were also represented. The majority of participants

reported being engaged in positions that require a mix

of technical knowledge, business understanding, and

communication skills.

Respondents came with a wide range of experi-

ence levels as depicted in Figure 3. Most represented

groups include employees with 2-3 and 12-15 years

of experience.

Figure 3: Years of experience.

About one third of the respondents (21) have

heard of the term “T-shaped” before.

When asked about the amount of coding required

in their daily jobs, which was to be indication a scale

from 1 (no coding) to 5 (pure coding). The results

(Fig. 4) show a wide distribution. The average rating

was 2.69 which would indicate that the job involves

coding, but the majority of the work consists of other

tasks. This highlights the varied nature of roles within

the organization, from non-technical positions to al-

most purely technical ones, emphasizing the need for

both deep expertise and a broader understanding of

multiple disciplines.

A question about interdisciplinarity uncovered

that a majority of employees still see one main skill

or discipline which dominates for them. Participants

were again asked to rate their jobs on a scale from one

(only one deep skill is required) to five (multiple dis-

ciplines combined) and the average rating was 3.45

(Fig. 4).

Additionally, employees were asked about the

alignment of their education with their current roles.

For those whose education did not align, the re-

T-Shaped Competencies in Academic and IT Service Synergies

733

ported level of multidisciplinarity was above average

(4), suggesting they had to develop a broader skill

set. This trend was also observed among respon-

dents identifying as Product Owners or Area Prod-

uct Owners, whose roles involve communicating with

numerous stakeholders from diverse knowledge back-

grounds.

When asked about the level of learning required,

where one symbolizes none and five represents con-

stant, continuous learning with no information reuse,

the majority of employees perceive their roles as re-

quiring frequent or continuous learning as shown in

Figure 4. This highlights the importance of ongo-

ing training and development opportunities to support

employees in maintaining and enhancing their skills.

Figure 4: Level of coding, multidisciplinarity, and learning

required.

Upon analyzing the results grouped by experience

levels, a notable trend was observed in the degree of

multidisciplinarity and the amount of required learn-

ing (Table 1). The data indicates that multidisciplinar-

ity increases with experience, as the highest scores

are consistently reported by the most seasoned em-

ployees. However, this pattern did not manifest in the

context of required learning, which remained signifi-

cantly high across all experience levels. Interestingly,

the least experienced group reported the lowest levels

of required learning.

Table 1: Multidisciplinarity and Required Learning based

on Experience Levels.

Experience Multidisciplinarity Learning

0–1 year 2.50 3.50

2–3 years 2.93 4.14

4–5 years 2.63 3.75

6–8 years 3.50 4.13

9–11 years 4.00 4.00

12–15 years 3.69 3.69

16–19 years 4.00 3.80

20+ years 4.13 4.38

The primary discipline for a vast majority of

respondents could be summarized as development.

When asked about which knowledge areas they

needed to incorporate into their secondary disciplines,

the most common answers consisted of Social Skills

(46 responses), Agile Principles (40 responses) and

Finance (40 responses). This is showing that ef-

fective communication and interpersonal skills are

critical for collaboration, teamwork, and stakeholder

management in this company. Other frequent re-

sponses include Project Management (34 responses)

and Databases (31 responses).

Another pattern was identified upon evaluating the

experience-level data. Respondents were asked to as-

sess their knowledge across multiple areas of their

job. The collected data suggests that technical knowl-

edge maturity, which is the primary discipline for

most participants identifying as developers, peaked in

the 9-11 years of experience group. Conversely, other

disciplines, which may be considered secondary, ex-

hibited continuous growth throughout the experience

levels, reaching their maximum in the most experi-

enced group (20+ years).

Over 80 % (53) of the participants actively seeks

out opportunities to learn about subjects outside of

their primary discipline. For those who do not (12),

the mentioned obstacles included time constraints and

limited access to resources, as many respondents cited

a lack of time to engage in deep learning outside of

their day-to-day responsibilities. The other reason

was the lack of purpose in acquiring those skills, as

there are dedicated experts in the field available or the

focus could rather be on building primary discipline

rather than diversifying.

Interestingly, even those who do not see the pur-

pose of acquiring these skills reported their roles as

multidisciplinary and could, therefore, benefit from

education in other domains. Focusing on raising

awareness of multidisciplinary education and enhanc-

ing employee motivation could provide significant

benefits for the company.

The majority of respondents (60 out of 65) re-

ported that interdisciplinary knowledge is very ben-

eficial or beneficial in their jobs. Many respondents

noted that knowledge in secondary disciplines helped

them communicate more effectively across depart-

ments, especially in project management, finance, and

customer interactions. Respondents emphasized that

having interdisciplinary skills helped avoid common

design or implementation issues. Their broader un-

derstanding often led to more creative solutions and

smoother project execution.

When asked about the significance of T-shaped

skills in light of emerging technologies like AI and

machine learning, 34 respondents believed that an in-

terdisciplinary approach will become increasingly im-

portant. They argued that as technology advances, the

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

734

ability to integrate technical expertise with broader

business or domain knowledge will be crucial for

staying competitive.

In response to whether companies should support

T-shaped learning, 54 respondents agreed that compa-

nies should actively support interdisciplinary learning

and help employees develop T-shaped competencies.

11 respondents were neutral on this issue, possibly

reflecting a lack of clarity on how interdisciplinary

learning might benefit them personally.

6 DISCUSSION

The growing recognition of T-shaped skills in

academia and business highlights their importance in

preparing individuals for a rapidly evolving world.

Traditional education models are being supplemented

with curricula that promote both depth and breadth

of knowledge, addressing modern challenges that re-

quire specialized expertise and interdisciplinary col-

laboration. Universities are adapting their programs

to cultivate T-shaped professionals with strong tech-

nical and soft skills. These professionals are invalu-

able in business environments, where their expertise

and flexibility help organizations remain agile, fos-

ter innovation, and address complex challenges. As

businesses prioritize adaptability and integrated ser-

vice models, the role of T-shaped professionals will

continue to expand, driving strategic growth and sus-

taining competitive advantage.

Our initial research shows that most IT profes-

sionals and academic researchers have T-shaped pro-

files, even if they don’t recognize the term. Using

soft skills, effective communication, and management

practices enhances teamwork and prevents issues. In-

tegrating T-shaped skills leads to innovative solutions

and efficient task execution, crucial for addressing

challenges in ICT, especially with the rise of AI and

machine learning.

However, the application of the T-shaped compe-

tencies in both environments may differ. In academia,

T-shaped professionals can benefit from an interdisci-

plinary approach, where integrating knowledge from

various fields can lead to groundbreaking discoveries

and innovative solutions. This approach allows aca-

demic researchers to collaborate effectively and ad-

dress complex problems from multiple perspectives.

On the other hand, in the business context, T-shaped

professionals may need to adopt a more multidisci-

plinary approach to remain flexible and adaptable.

Businesses often require professionals who can col-

laborate across different functions and domains with-

out necessarily integrating their methodologies. This

flexibility allows businesses to respond quickly to

changing market demands and maintain a competitive

edge. However, this hypothesis requires further in-

vestigation to determine the optimal balance between

interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches in

different contexts.

The presented case studies are an initial step in re-

searching T-shape competencies across IT-based aca-

demic and professional domains. Ongoing and future

case studies in various industries and universities will

provide insights into the roles, challenges, and bene-

fits of developing T-shaped professionals.

7 CONCLUSION

Integrating diverse expertise and collaborating across

disciplines is essential for addressing the complex

challenges of the 21st century. This paper highlights

that T-shaped competencies are crucial in fostering in-

novation and driving value co-creation.

In conclusion, interdisciplinary or multidisci-

plinary education and knowledge skills are fundamen-

tal sources of competitive advantage in both academic

and business contexts. Interdisciplinary approaches

are more typical for academia, where the integration

of knowledge from various fields can lead to inno-

vative solutions. In contrast, multidisciplinary ap-

proaches are more typical for business, where flex-

ibility and adaptability are crucial for responding to

changing market demands. To fully leverage the

benefits of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary ap-

proaches, it is imperative to investigate the specific

knowledge and skills required for success in various

business domains. This investigation will help iden-

tify the key competencies needed to thrive in a rapidly

evolving landscape.

Furthermore, a more intensive collaboration be-

tween academia and business is necessary to spec-

ify and continuously update the required knowledge

and skills. The dynamic nature of the modern world

means that the specific set of competencies will

change over time, necessitating a clear mechanism

for adaptation. This ongoing collaboration will en-

sure that both academic curricula and business prac-

tices remain relevant and effective. It is evident that

no single domain, whether academia or business, can

address the entirety of complex problems alone. The

synergy between these domains is essential for holis-

tic problem-solving and innovation. By working to-

gether, academia and business can better understand

the challenges and develop more effective solutions.

Finally, the advent of AI tools, particularly large

language models (LLMs), presents both opportuni-

T-Shaped Competencies in Academic and IT Service Synergies

735

ties and challenges for multidisciplinary skills. While

these tools can enhance productivity and provide

valuable insights, they also necessitate reevaluating

the skills required for success. Understanding how AI

will impact multidisciplinary competencies is a criti-

cal area for future research and adaptation.

In summary, fostering multidisciplinary and in-

terdisciplinary education and collaboration between

academia and business is vital for addressing the com-

plex challenges of the modern world. We can create a

more innovative and resilient future by continuously

updating the required knowledge and skills and lever-

aging the potential of AI tools.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have used AI language tools to check the

grammar and enhance the formulation of the text.

REFERENCES

Amber, D. (2000). Researchers seek basics of nano scale.

The Scientist.

Barile, S., Saviano, M., and Simone, C. (2014). Service

economy, knowledge, and the need for t-shaped inno-

vators. World Wide Web, 18:1–21.

Bierema, L. (2019). Enhancing employability through de-

veloping t-shaped professionals. New Directions for

Adult and Continuing Education, 2019:67–81.

Boehm, B. and Mobasser, S. (2015). System thinking: Ed-

ucating t-shaped software engineers. pages 333–342.

Brown, T. (2010). T-shaped stars: The backbone of ideo’s

collaborative culture. Chief Executive (U.S.).

Conley, S., Foley, R., Gorman, M., Denham, J., and Cole-

man, K. (2017). Acquisition of t-shaped expertise: an

exploratory study. Social Epistemology, 31(2):165–

183.

Demirkan, H. and Spohrer, J. (2015). T-shaped innovators:

Identifying the right talent to support service innova-

tion. Research-Technology Management, 58(5):12–

15.

Demirkan, H. and Spohrer, J. C. (2018). Commen-

tary—cultivating t-shaped professionals in the era of

digital transformation. Service science, 10:88–109.

Freund, L., Spohrer, J., Savva, P., and Gandhi, Y. (2024). T-

shaped professionals: The past, present, and future of

myt-me development. In Leitner, C., N

¨

agele, R., Bas-

sano, C., and Satterfield, D., editors, The Human Side

of Service Engineering, volume 143 of AHFE Open

Access, USA. AHFE International.

Gardner, P. (2017). Flourishing in the face of constant dis-

ruption: Cultivating the t-professional or adaptive in-

novator through wil. In Work-Integrated Learning in

the 21st Century, volume 32 of International Perspec-

tives on Education and Society, pages 69–81. Emerald

Publishing Limited, Leeds.

Guest, D. (1991). The hunt is on for the renaissance man of

computing. The Independent.

Joly, M. P., Teixeira, J. G., Patr

´

ıcio, L., and Sangiorgi, D.

(2019). Leveraging service design as a multidisci-

plinary approach to service innovation. Journal of

Service Management, 30(6):681–715.

Kruusmaa, M. (2017). On Informatics, Diamonds and T,

pages 27–36.

Kunze, T., Stadler, M., and Greiff, S. (2023). A look at

complex problem solving in the 21st century. NSW

Department of Education.

Mirafzal, M., Wadhera, P., and Stal-Le Cardinal, J. (2023).

An exploration of knowledge management activities

in multidisciplinary service design organizations. Pro-

ceedings of the Design Society, 3:525–534.

Ninan, J., Hertogh, M., and Liu, Y. (2022). Educating en-

gineers of the future: T-shaped professionals for man-

aging infrastructure projects. Project Leadership and

Society, 3:100071.

Robam, K., Hand, T., and Karu, V. (2023). Why t-shaped

engineers in the mining sector are vital for progress.

ENVIRONMENT. TECHNOLOGIES. RESOURCES.

Proceedings of the International Scientific and Prac-

tical Conference, 2:193–195.

Sanchez, C. A., Ruddell, B., Schiesser, R., and Merwade,

V. (2016). Enhancing the t-shaped learning profile

when teaching hydrology using data, modeling, and

visualization activities. Hydrology and Earth System

Sciences, 20:1289–1299.

Saukkonen, J. and Kreus, P. (2022). T-shaped capabilities

of the next generation: Prospecting for an improved

model. European Conference on Knowledge Manage-

ment.

Saviano, M. and Barile, S. (2013). Dynamic Capabili-

ties and T-Shaped Knowledge: A Viable Systems Ap-

proach, pages 39–59.

Saviano, M., Polese, F., Caputo, F., and Walletzk

´

y, L.

(2016). A t-shaped model for rethinking higher ed-

ucation programs.

Spohrer, J., Maglio, P. P., Bailey, J., and Gruhl, D. (2007).

Steps toward a science of service systems. Computer,

40(1):71–77.

Tranquillo, J. (2017). The t-shaped engineer. Journal of

Engineering Education Transformations, 30:12–24.

Uhlenbrook, S. and Jong, E. (2012). T-shaped competency

profile for water professionals of the future. Hydrol-

ogy and Earth System Sciences Discussions, 9:22.

Walletzk

´

y, L., Schwarzov

´

a, Z., Marschalkov

´

a, J., and

Kub

´

ı

ˇ

ckov

´

a, K. (2024). Role of t-shape in it academic

research. In Leitner, C., N

¨

agele, R., Bassano, C., and

Satterfield, D., editors, The Human Side of Service En-

gineering, volume 143 of AHFE Open Access, USA.

AHFE International.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

736