Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis

Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

Sunny K. O. Miranda

a

, Maria José Marcelino

b

and Paula Alexandra Silva

c

University of Coimbra, CISUC/LASI, DEI, Coimbra, Portugal

Keywords: IT Course Choice, IT Major, Career, Social Cognitive Career Theory, Gender Differences.

Abstract: This study investigates what influences students to choose IT-related courses, focusing on gender differences

within the Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) framework. Gender disparities in IT are a significant

problem in most European countries despite the growing demand for qualified professionals. In 2023, only

20% of employed ICT specialists in Portugal were women. Attracting and retaining female students in IT

programs remains a challenge. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors motivate students to pursue IT courses.

SCCT identifies prior experience, social support, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations as critical influences

on higher education and career selection. This study surveyed how these factors affect IT course choices,

considering gender differences. It involved 56 Portuguese IT-related students from two higher education

institutions in 2023. Using thematic analysis, we examined twenty open-ended questions to identify the

reasons behind choosing IT. The results showed that previous programming experience, exposure to

IT/computer, personal interest and positive job prospects significantly influenced decisions, while support

from parents, friends and teachers was less impactful. The study suggests that educators and policymakers

should intensify computing activities for school students, especially girls, to foster interest and attract them

to IT careers, enriching the sector with diverse perspectives and talents.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information Technology (IT) degrees are a gateway

to countless career opportunities and innovations

today. Fields such as Informatics Engineering,

Electrotechnical and Computer Engineering, Data

Science, and Design and Multimedia are essential to

advancing technological frontiers and addressing

global challenges. However, despite the growing

demand for skilled professionals in these fields, there

is still a significant gender gap (Spieler et al., 2020;

Babeş-Vroman, 2021; Chen et al., 2023; Eurostat,

2024) that limits the potential for diverse perspectives

and innovations.

Like most European countries, Portugal ICT

workforce is predominantly male, with only 20% of

employed ICT specialists were women in 2023

(Eurostat, 2024). This lack of diversity hinders a more

innovative environment and makes the field less

attractive to women. This percentage reflects the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4916-5618

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1989-5559

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1573-7446

entry of new students into higher education in ICT at

Portuguese universities, where only 18% of students

were women in Portugal's 2022/2023 academic year.

This begs the question: why do so few Portuguese

women choose to pursue an IT degree?

Promoting diversity in IT becomes crucial to

fostering an inclusive culture that values different

perspectives and ideas (Spieler et al., 2020; Babeş-

Vroman, 2021). A diverse workforce can drive

innovation by bringing varied experiences and

viewpoints to problem-solving processes.

Furthermore, as technology increasingly influences

all aspects of society, its creators must reflect the

diversity of its users.

Considering the Social Cognitive Career Theory

(Lent & Brown, 2019), several variables, including

personal (emotional state, gender role attitudes),

contextual (perceived social supports and barriers),

and cognitive (self-efficacy beliefs, outcome

expectations), interests, and goals, influence the

Miranda, S. K. O., Marcelino, M. J. and Silva, P. A.

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory.

DOI: 10.5220/0013292900003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 881-892

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

881

decision to pursue a specific field of study. For IT

majors, these decisions are further complicated by

biases, stereotypes and cultural norms (Master et al.,

2020; Kube et al., 2024) that often discourage

underrepresented groups, particularly women (Chen

et al., 2023), from entering these fields.

In this context, the current study is motivated by

the need to understand better the factors that influence

Portuguese students' decisions to choose IT-related

courses based on the Social Cognitive Career Theory

framework.

Our findings will provide a more comprehensive

understanding of fostering diversity and inclusion

across IT disciplines. They will help educators and

policymakers better understand how to create

supportive environments that encourage all students

to consider careers in IT, ultimately contributing to a

more inclusive, innovative, and competitive

technology future.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

2.1 SCCT Framework

Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT), introduced

by Lent, Brown, and Hackett in 1994, builds on

Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory to explain and

predict academic and career development. Initially,

SCCT focused on how individuals develop

educational and vocational interests, make career

choices, and function in academic and work

environments. Over time, it has been refined to

include well-being, job satisfaction, and educational

and career self-management, resulting in five

comprehensive models (Brown & Lent, 2023).

Each model incorporates personal, behavioural,

and environmental variables. Key personal variables

include self-efficacy beliefs and outcome

expectations that guide career-related efforts.

Self-efficacy beliefs are domain-specific

cognitive representations of personal competencies

that reflect an individual’s confidence in succeeding

in various activities (Bandura, 1986). These beliefs

motivate behaviour by influencing choices, effort,

persistence, and overall performance. They are

developed through observing similar role models,

experiencing success, receiving encouragement, and

managing anxiety.

Outcome expectations are the perceived

consequences of engaging in activities within

different domains (Bandura, 1986). They are also

domain-specific, motivational, and adaptive, and can

be positive or negative and categorized into extrinsic,

intrinsic, social, or self-evaluative outcomes and

motivate engagement and persistence. A combination

of self-efficacy beliefs and positive outcome

expectations significantly motivate decisions, such as

selecting a STEM major (Brown & Lent, 2023).

Environmental variables, such as social supports

and barriers, affect career choices and help shape self-

efficacy and outcome expectations (Brown & Lent,

2023).

Learning experiences, another SCCT element,

involve engaging with and acquiring skills through

formal or informal education, practical application,

and personal exploration. These experiences

influence an individual's self-efficacy and

expectations of outcomes in various domains (Brown

& Lent, 2023).

In the SCCT interest and choice models (Lent et

al., 1994; Lent & Brown, 2019), self-efficacy is

crucial for shaping outcome expectations, as

competent individuals tend to foresee favourable

outcomes. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations,

individually or combined, predict interests by

promoting sustained engagement in activities

anticipated to yield positive results, such as personal

fulfilment and social recognition. These factors help

individuals set goals for future endeavours, like

selecting a college major or career aligned with their

interests. Furthermore, environmental supports and

barriers significantly affect these goals, as career-

related achievements often depend on the social,

material, and financial resources or obstacles present

in the environment.

2.2 Related Work

Researchers have investigated several factors that

could explain gender disparities in occupational

engagement in STEM/IT fields. These factors include

low self-efficacy, negative outcome expectations, and

distal and proximal contextual influences on

academic/career choices. SCCT has been

instrumental in investigating interests, choices, and

persistence in STEM/IT fields for underrepresented

groups such as women and racial/ethnic minorities

(Fouad & Santana, 2017; Lent et al., 2018).

Researchers found that self-efficacy had a slightly

more potent influence on outcome expectations

among men, whereas the impact of supports and

barriers was more pronounced for women (Lent et al.,

2011). This suggests that female computing students'

outcome expectations are more affected by

perceptions of environmental conditions and work-

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

882

family balance, with social support playing a crucial

role in overcoming barriers in their pursuit of

computing degrees.

Five environmental supports and barriers were

identified (Fouad et al., 2010): parental, school,

financial/environmental, social, and individual.

Barriers negatively impacted self-efficacy more in

men than in women, while supports were more

positively linked to outcome expectations and goals

in most samples (Lent et al., 2018). Parental support

and learning experiences are essential for self-

efficacy in mathematics and science (Fouad &

Santana, 2017). This self-efficacy is also connected to

outcome expectations, influencing interest and

intentions to pursue STEM careers. Research

suggests that increasing parental involvement in

interventions can increase interest in STEM (Fouad &

Santana, 2017). Initiatives to improve women’s self-

efficacy in STEM can focus on providing social

support that helps mitigate the impact of barriers

while strengthening outcome expectations, interests,

and career choices (Lent et al., 2018).

Research has found that outcome expectations

were more closely linked to interests in majority

groups but more strongly linked to goals in minority

samples (Lent et al., 2018). As an example of

outcome expectations, perceived job availability

influenced personal utility more than expected salary

or job security (McKenzie and Bennett, 2022).

Alshahrani et al. (2018) explored why students

choose to study Computer Science (CS) using SCCT

constructs by interviewing 17 mixed-gender students

at Scottish universities. They found that social

support from family, teachers, friends, and mentors is

crucial for women to pursue CS. These findings are

like those of Tsakissiris and Grant-Smith (2021) but

contrary to those of McKenzie and Bennett (2022),

who found that social influences such as family and

friends were not significant motivators in studying IT.

Furthermore, the career opportunities provided by a

CS degree, including job prospects and the potential

to make significant social contributions, were

significant motivators. Prior experiences such as

problem-solving, programming, online self-study,

and internships positively influenced their decision,

while school education had a limited impact.

McKenzie and Bennett (2022) conducted a two-

year study of undergraduate IT students' course

selection and career aspirations at an Australian

university. The findings revealed that students’

motivation to study IT is primarily driven by an

intrinsic interest and enjoyment of the field rather

than external factors such as salary or job security.

This focus on personal factors aligns with previous

research (e.g., Tsakissiris & Grant-Smith, 2021).

Smit et al. (2024) examined how enjoyment

predicts students’ self-efficacy in programming.

Students with lower initial enjoyment scores

experienced more significant increases in enjoyment

during the final tasks than those with higher initial

scores. While girls’ enjoyment scores increased more

than boys’, girls’ overall enjoyment scores remained

lower. Both genders saw an increase in self-efficacy

beliefs over the course, with some variation in these

beliefs attributable to enjoyment of the course. Atiq

and Loui (2022) found that the predominant emotions

during the programming task were frustration,

anxiety, confusion, neutrality, and relief.

Tsakissiris and Grant-Smith (2021) conducted in-

depth semi-structured interviews with 52 ICT

students from four Australian higher education

institutions. The findings reveal that emerging

professional identity factors (such as mastery, sense

of belonging and status, and esteem) and self-interest

factors (such as anticipated income, perceived

opportunities, and work-life balance) collectively

exert significant influence, pushing students away

from or pulling them towards pursuing an ICT career

after graduation.

Despite extensive study of SCCT models of

interest and choice, further research is required to

evaluate their applicability in diverse demographic

and cultural contexts. It is also necessary to explore

new intersections between variables such as learning

experiences, social support, self-efficacy beliefs, and

outcome expectations, particularly regarding IT-

related course selection and gender differences.

3 METHODS

3.1 Goals and Research Questions

This exploratory research investigates how learning

experiences, social support, self-efficacy beliefs, and

outcome expectations affected Portugal university

students' choice of higher education courses in IT

areas. To achieve this objective, the following

research questions were formulated:

RQ1: How do prior experiences shape students'

decisions to choose IT-related courses, and

what gender-specific differences affect this

impact?

RQ2: How does social support from family,

peers, and educators influence students' choices

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

883

to pursue IT courses, and how does this impact

vary by gender?

RQ3: How do self-efficacy beliefs influence

students' decisions to pursue IT courses, and

what factors impact these beliefs, particularly

regarding gender differences?

RQ4: How do outcome expectations shape

students' decisions to choose IT courses, and

what gender-specific differences exist in

perceptions of career opportunities in these

fields?

RQ5: How do students’ perceptions of IT culture

and stereotypes affect their course choices,

especially for underrepresented genders?

RQ6: What suggestions do students have for

parents, schools, and universities to support

and recruit more underrepresented groups into

IT courses?

3.2 Recruitment and Participants

After authorization from the ethics committee and

approval from the data protection office of the

authors' institution, we recruited participants.

The participants invited to this study were all

students at all university levels (undergraduate to

doctorate) and over 18 years old enrolled in IT-related

courses, including Informatics Engineering,

Electrotechnics and Computer Engineering, Data

Science, and Design and Multimedia from two higher

education institutions in Portugal.

Participants were recruited through outreach

efforts, including posters and flyers delivered directly

by the researcher and emails sent by the student's

department secretary or director. Participants were

assured of their anonymity and informed that their

participation was voluntary. Informed consent was

required from all study participants. No financial

incentives or other benefits were offered, relying

solely on the participants' willingness to contribute to

scientific research.

There were 56 participants, identified as follows:

man (M) - 35, woman (W) - 19, non-binary or

preferably not specifying gender (NI) – 2. All

participants were Portuguese students who were

actively enrolled and reported being studying or

having studied the following undergraduate courses:

Informatics Engineering (M-18, W-7, NI-1),

Electrotechnical and Computer Engineering (M-10,

W- 4, NI-1), Design and Multimedia (M-3, W-2),

Data Science and Engineering (W-3) and Others (M-

4, W-3) (see details in Table 1). The participant pool

consisted of 33.3% female and 63.2% male students,

along with 3.6% who identified as non-binary or

preferred not specifying gender. This distribution

reflects the study’s focus on exploring gender

differences in IT major choices. Participants ranged

in age from 18 to 43, with the majority falling within

the typical 18-23 age range for undergraduate

students. The study included students from a variety

of academic levels, including undergraduate (53.6%),

master’s (30.4%), and doctoral (16.1%) degrees.

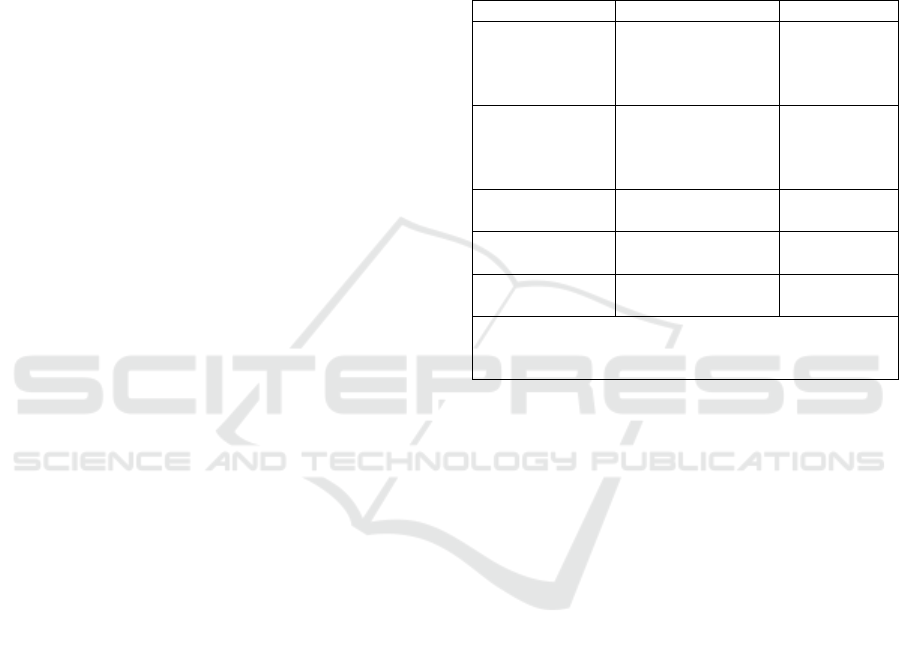

Table 1: Participant demographics.

Course N Age*

Informatics

Engineering

26

(M-18, W-7, NI-1)

18 to 23

(53.84 %)

24 to 28

(30.76

%)

Electrotechnical

and Computer

Engineering

15

(M-10, W-4, NI-1)

18 to 23

(73.33 %)

24 to 28

(

13.33%

)

Design and

Multimedia

5

(M-3, W-2)

18 to 23

(100%)

Data Science

and Engineering

3

(W-3)

18 to 23

(100%)

Others 7

(

M - 4, W - 3

)

18 to 23

(

71.42%

)

N = 56; M (men) = 62.5 %; W (women) = 33.9 %.

NI (not binary or not specified) = 3.6%

* Other age ranges omitted due to space constraints

3.3 Data Collection and Instruments

Data was collected through an online survey with an

extensive questionnaire that will be used for a broader

study in the future. However, this article will focus on

analysing a specific block of 20 open-ended questions

in addition to demographic data.

The block of 20 open-ended questions was

adapted from Alshahrani et al. (2018) and translated

from English to the Portuguese context. Bilingual

experts (Portuguese - English) reviewed and

validated the questions. The questionnaire was then

pilot tested with a sample of the target audience.

This block of questions explores the SCCT

constructs that influenced the decision to pursue an IT

course through questions about prior experiences in

school and with IT before entering university, social

influences and support, self-efficacy beliefs and

outcome expectations, as well as questions to collect

participants' perceptions and suggestions about the IT

field and society's view on gender disparity in this

area. This approach allowed participants to express

themselves, providing rich qualitative insights into

their experiences and perspectives.

The survey was conducted using the Lime Survey

platform. It was available to students at all

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

884

educational levels in the departments involved, from

undergraduate to doctoral, over the course of two

months, from November to December 2023.

3.4 Data Analysis

This qualitative study analyses open-ended questions

related to SCCT constructs and gender differences.

Demographic data were analysed using

descriptive statistics to count, calculate the

percentage and summary of responses.

Data from open-ended questions were analysed

using a mix of deductive and inductive thematic

analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) that guided this

study. The steps for thematic analysis are explained

as follows.

Familiarization with the Data: Participant

responses were exported from Lime Survey to an

Excel spreadsheet. The Excel spreadsheet was

adjusted to include only participant demographics

and the block of 20 open-ended questions. In

addition, any missing data or respondents who were

not part of this research's target audience were

removed. After that, fifty-six documents

corresponding to the responses of the 56 participants

were imported into Atlas.ti. Then, the data were

prepared to be read, analysed and coded.

Generating Codes and Categorization: Most of

the coding emerged from the data, but its construction

was influenced by previous research (Alshahrani et

al., 2018; Lent & Brown, 2019). Coding was aided by

Atlas.ti and attempted to capture the most meaningful

terms and organize them into groups. The coding

process was based on the responses to each question

in the questionnaire, previously associated with a

general theme, such as prior experiences, social

support, selfie-efficacy, outcome expectations,

perceptions and suggestions. As results, 370 codes

were generated and assigned in 984 citations.

Defining and Reviewing Themes: The codes were

grouped into potential themes (or subcategories) by

combining all relevant data for each theme and

identifying patterns and insights related to the research

questions in this study. In addition to the themes

previously defined by the questionnaire, new themes

emerged from the analysis and were considered. As a

result, twenty-two relevant themes were identified, and

excerpts were associated with them.

Producing the Report: Finally, a coherent

narrative was constructed considering the defined

themes and subthemes and supported by selected

quotes to provide a compelling account of the

findings, as seen in the results section of this paper.

4 RESULTS

This section presents the results to our research

questions according to four SCCT constructs: prior

experience, social support, self-efficacy, and outcome

expectations, along with additional categories of

perceptions and suggestions.

Data are presented using example quotations from

students who responded to the questions. The

following codes were defined to maintain

respondents' anonymity: PM#0 indicates a male

participant, PF#0 indicates a female participant, and

P

NI#0 indicates a non-binary participant or

participant who did not wish to provide their gender,

followed by an identification number. It is essential to

clarify that the questions were not mandatory, leaving

the research participants free to answer what they

wanted; therefore, not all participants answered all

the questions. The students' statements presented here

were freely translated from Portuguese to English.

4.1 Prior Experiences

In response to RQ1: How do prior experiences shape

students' decisions to choose IT-related courses, and

what gender-specific differences affect this impact,

participants’ responses were categorised into the

following six themes: IT Classroom Environment;

Types of Activities with IT Resources; Specific

Programming Course Before Higher Education;

Decision-Making Moment of Choosing The Course;

The importance of Prior Experiences in Influencing

Their Decision; and Reasons and Most Significant

Influencing Factors.

Twenty-one respondents associated the IT

Classroom Environment during their school years

with a negative evaluation, describing an unpleasant

atmosphere, unmotivating lessons and teaching of

basic computer use and software applications. Ten

highlighted the lack of preparation of teachers for

teaching IT and the use of only basic computer

resources: "There was still a lot of immaturity

regarding the use of IT in classes at school, even

though I studied in an environment with a lot of

exposure to it from an early age. The teachers also

did not yet have the training or competence to know

how to manage these dynamics, nor the appropriate

tools (computers not managed by the school, etc.) to

keep students focused on the activities in question.”

(PM#16). Eight participants evaluated the IT

Classroom Environment positively and noted that it

influenced their connection with IT: "I learned the

basic concepts of IT, used programs considered for

daily use, and superficially developed a website and

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

885

a simple robot. These activities were, in a way,

important for my initial connection with IT.”

(PM#32) Five students took programming classes at

school: "In high school, with the subject Informatic

Applications B, I developed a Media Player for video

and audio files using C#. This was indeed very useful

for the course I am currently studying.” (PF#9).

Only nine of the 56 participants said they had

taken specific programming courses before entering

higher education, and only two were women.

Fourteen respondents said they decided to pursue an

IT degree during high school. In contrast, others

indicated it was during elementary school (6) and

others (4) at the time of applying to higher education.

Twenty-nine said they had or were interested in

another course/field of study, while nine stated that

the chosen course was their first choice.

Twenty-nine respondents commented on the

importance of previous experiences in influencing the

decision to choose a course and highlighted contact

and experience with IT and equipment (9) as the main

factors: "I always grew up with computers, and by

primary school, I had already started programming

some basic games, so the decision was almost a

given."(PM#16); "I did some electronics projects in

high school that solidified my choice of

course."(PF#6); "The experience that most

influenced me to choose informatics engineering was

having the informatics applications subject in the

12th grade, as I learned to program in Python, make

simple animations with Pivot Animator, and edit

vector images, among other things, but these were the

activities I enjoyed the most."(PNI#2) However,

seven students (M=4, W=3) responded that previous

experiences did not influence their decision to pursue

an IT course. “I didn't have any experience that

influenced me. It was purely by process of

elimination."(PF#11); “It wasn't because of the past,

but because of the work opportunities in this area."

(PM#22); They did not influence me at all. I wasn't

influenced by experiences, only by people and

facts."(PF#12)

Participants responded that personal interest (17)

and good job prospects (14) were the most significant

factors influencing their choice of higher education

courses: "Personal interest, curiosity, a liking for the

sciences and exact areas, a liking for technology and

everything associated with it." (PF#9); "The biggest

influence on my choice of this degree was the fact that

it is a growing field, with above-average salaries and

many job opportunities." (PM#29); "Passion. The

combination of art with technology (design and

multimedia)." (PM#4); "The job opportunities and

their remuneration are good, and I had a great

interest in learning more about this area." (PM#13)

4.2 Social Support

In response to RQ2: How does social support from

family, peers, and educators influence students'

choices to pursue IT courses, and how does this

impact vary by gender, participants’ responses were

categorised into the following three themes: Influence

of Parents, Influence of Close People or Friends, and

Influence of Teacher.

Eight participants (M=4, W=3, NI=1) mentioned

the influence of others on their course choice. Of

these, 4 mentioned the influence of family: "In part, I

was influenced by my father's experience, who is an

electrical engineer, and from an early age, he talked

to me about his field and his course." (PM#13); "the

experience of family members as computer engineers

also helped" (PNI#2); "Seeing my mother working in

the field." (PM#10); “My father, who earned a degree

in Electrotechnical and Computer Engineering,

which is more or less in the field, also influenced my

choice, reinforcing my professor's opinion.”

(PF#12). Three mentioned the influence of close

people or friends: "obviously, I took the second path

and later entered Informatics Engineering, largely

due to the influence of those close to me and the job

prospects." (PM#17); "Encouragement from a

friend/colleague." (PM#30). Only one mentioned the

influence of a teacher: "My teacher, whom I hold in

high regard and esteem, not only recommended this

course to me but also spoke very highly of it."

(PF#12) However, one cited the discouragement from

teachers: "I was always encouraged to go into the

health field and not technology, mainly by my

teachers."(PF#2)

4.3 Self-Efficacy

In response to RQ3: How do self-efficacy beliefs

influence students' decisions to pursue IT courses,

and what factors impact these beliefs, particularly

regarding gender differences, participants’ responses

were categorized into the following four themes:

Confidence in the Ability to Study the IT Course;

Beliefs about the IT field; Programming Skills; and

Feelings about Being an IT Student.

Twenty-eight of those respondents said they were

very confident: “Very confident because I really

enjoy everything I learn and work on in this area.”

(PM#6); “Very much. I don’t see much reason why I

couldn’t do it if I wanted to.” (PF#6) Others said they

were confident (6) or relatively confident (3):

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

886

“Confident when it comes to programming and

problem-solving, not so confident when it comes to

more theoretical things.” (PM#34); “Confident

enough to continue achieving my personal and

professional goals.” (PF#9). Another said he wasn't

very confident. Although some women and men rated

themselves highly, only three women rated

themselves with the lowest degree of confidence:

“Very little, honestly.” (PF#12); “Not at all

confidence.” (PF#10). “Trust 0.” (PF#11)

Regarding student's beliefs about the IT field,

responses were sub-categorized into the following

themes. The importance of IT: "The importance of

studying in this area and its relevance to the future of

technology has become increasingly clear."

(PM#13); "I think it's an important area that has a

significant impact on various parts of society."

(PF#3); Interesting area: "It's interesting, there's still

much to discover/create." (PM#20); Area that

requires dedication: "It's demanding but not difficult

if we are consistent." (PF#16) "Nothing is impossible,

it just requires dedication and time." (PF#19)

Participants were asked about their programming

skills, whether they enjoyed programming and

whether this could influence their choice to enter the

IT field. Twenty-one responded that they have good

skills and enjoy programming. However, a lack of

skills does not prevent them from choosing a course,

although it helps. "I feel that my skills are good. I had

several classmates with zero experience in

programming, and with help and study, they easily

reached the level I had acquired before entering

higher education." (PM#26); "Programming was

something I had never 'done.' I entered the first year

with no experience, but with effort, I succeeded, and

it is one of the things I like the most." (PF#14); "I

think I have good logical reasoning and that I will be

a good programmer." (PF#18) Two respondents

mentioned that they had basic skills: "Very basic

skills, I have a lot of interest and enjoyment, but it's

complicated since there's a lot of material and it's

taught very quickly." (PM#30); "I know the basics,

but I'm ready to learn MORE." (PM#36). Meanwhile,

three boys claimed to have advanced skill: "My

programming skills are advanced." (PM#7); "At this

point, I am already competent at programming."

(PM#27); "I am a quite capable programmer."

(PM#16) Two responded that they don't like it and are

not good at it: "I'm not good, I don't like studying

Programming, but I hope it's just the initial impact

and that it will get better over time." (PF#12); "It's

not the most pleasant, but it's one of the most

important." (PM#22)

Participants were asked how they felt about

studying a course related to IT. The subthemes

identified were as follows. Happy (3): "I feel

somewhat happy to be doing something I like."

(PM#8); "I feel proud and happy to be challenged."

(PM#13) Good (7): "Currently, studying Informatics

Engineering makes me feel very good, as I'm always

discovering new applications of various concepts,

and it doesn't seem like this will change anytime

soon." (PM#17); Fulfilled (4): "Fulfilled by achieving

my goals in courses and in life." (PM#10); "I feel

fulfilled with what I am learning, unlike all the

education before higher education." (PF#9)

Frustrated (2), Tired (2), but Satisfied: "I couldn't be

studying anything better; each day I may get tired, but

it's worth it." (PF#17); "Frustrating, rewarding,

tiring, inspiring." (PF#7); “Sometimes there are

some frustrations since there are errors that are not

perceptible. On the other hand, there is enormous

satisfaction when things go well. In terms of self-

esteem, I feel good about myself and motivated to be

studying to become a future informatic engineer."

(PM#35) Confident about the future (4): "Confident

that this path will open many doors for me." (PF#15);

"I feel that I am studying an area that will help me

improve the world and people's lives in the future."

(PNI#2); "I feel somewhat relieved regarding

employability in this area." (PF#19); Normal (2) or

nothing special (2): “I feel normal, neither more nor

less happy; it's a good area with very interesting

moments and others that are more boring." (PM#5);

"Neutral. It doesn't make me feel anything special."

(PM#25)

4.4 Outcome Expectations

In response to RQ4: How do outcome expectations

shape students' decisions to choose IT courses, and

what gender-specific differences exist in perceptions

of career opportunities in these fields, participants’

responses were categorised into the following three

themes: Outcome Expectations (Employment and

Salaries, Contributing to society, and Personal and

Professional Success); Influence of Outcome

Expectations on the Choice of Higher Education

Course; and Attractive IT Careers for Women.

Participants referred to Employment and Salaries

(23) as the most impactful expected outcome they

hope to achieve by pursuing an IT course: "Obtaining

a higher-paying job, more opportunities for growth,

and personal development." (PM#28); "A good job,

new challenges, and new opportunities. I hope to

become a competent professional and fulfilled with

what I do in my day-to-day life." (PF#9); The second

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

887

theme was Personal and professional success (7):

"Personal and professional success and a good living

condition for me and my family." (PM#6); "Success

on all levels." (PM#36). Contributing to society (4):

"A contribution to society." (PF#7); "I hope to be able

to do things to help people and have a stable job that

gives me security. I also hope to meet more people

like me who see this area as a way to create incredible

things and help others." (PNI#2).

Twenty-nine participants agreed when asked

whether the outcome expectations they mentioned

could influence students to study IT. "Yes, it seems to

me that the pleasure in acquiring and disseminating

knowledge in the area is what contributed to getting

here." (PM#17); "Yes, it's always important to

consider expectations regarding job availability in

the field." (PF#9); "Yes, I think if someone has

expectations of good results, they will want to study

in this area." (PNI#2); "Of course, good expectations

lead to the creation of dreams." (PM#15). Two said

it depended on the student: "It depends a lot on the

student's goals. For many people, academia is not the

right path and a career in programming can be

daunting." (PF#3); "It depends on the student's

willingness and interest in the area." (PM#35).

Students were asked what they knew about

careers with a degree in IT and whether they were

attractive careers for women. Twenty-two said the

careers were equally attractive to both sexes: "They

are equally attractive for women as for men. I don't

notice, for example, a salary difference. Companies,

when hiring, don't ask for a 'man' or a 'woman.' They

ask for someone qualified."(PM#2); "They allow for

a motivating and dignified career with access to good

living conditions. I think so, both for men and women.

Because the field itself doesn't make that gender

separation at any point."(PM#6); "I know they are

promising, and I think they are attractive to anyone

who knows them."(PM#13); "It's possible that they

are attractive, yes. There are many IT jobs that are

done remotely, I imagine that is very useful for a

mother, for example."(PM#15); "Yes, but it is still an

area controlled by men."(PF#1); "Yes, there are

quotas to fill."(PF#2); "I don't see a difference in

attractiveness between sexes; they are generally

attractive careers."(PF#15); "I know it's a well-paid

area and that, because there is a quota of women that

companies have to fill, it's easier for a girl to be

hired."(PF#18) Three responded regarding the

environment: "As a woman, I think it's a 'double-

edged sword' situation. By that, I mean the salary can

be attractive, but the toxicity associated with these

environments can be demotivating."(PF#19); "No,

due to possible social environments, negative for

women, but if they have enough interest, I don't think

it's enough to deter the decision."(PM#21) "No. It's

still a very male-dominated world. Many men who

work in the area are and usually have power."(PF#6)

Six participants said they had no idea about this topic.

4.5 Perceptions

In response to RQ5: How do students’ perceptions of

IT culture and stereotypes affect their course choices,

especially for underrepresented genders, participants'

answers were captured regarding the following four

themes: The Importance of IT at School and Early

Exposure; How IT students are Seen by Society;

Reasons Why IT Courses don't Attract Women;

Differences between Being a Boy and Being a Girl in

Receiving Support from Family or Society to Study

IT.

Participants emphasized the importance of IT

education in schools, particularly the need for Digital

Literacy (26). They highlighted the benefits of early

exposure to IT (8) and advocated for including

Computer in the curriculum (7): "Yes. In my opinion,

with the great evolution in the field of computing, I

think it's important to learn a bit about programming,

robotics, and artificial intelligence to be prepared to

interpret the future problems of the world and to

understand what is happening around us and behind

the devices we use."(PM#35). Conversely, three

respondents (M=2, W=1) suggested that IT should be

taught only to those who show interest.

Regarding the society view of IT students,

participants positively point out that IT students are

seen as intelligent (4), well-regarded (2), capable (2):

"In my circle of acquaintances, they are seen as

students dedicated to learning a bit of everything they

can." (PM#10); "Technology students are considered

very intelligent because they use knowledge of

mathematics and science to solve problems."(PF#33)

Negatively, IT students are often stereotyped as nerds

(11), in addition to other negative characteristics:

"Nerds, antisocial, and strange people. I understand

because after spending so much time on a project, I

also feel strange and antisocial (not a nerd)."(PM#3);

"I don't agree because I think there's still a strong

notion that it's a field more suitable for males, and

there's also that typical stereotype associated with

programmers—basically a (male) person without

social skills, who is a 'nerd,' has poor

hygiene/appearance, and does nothing but

program."(PF#19)

Respondents attribute gender disparity in IT field

to several factors. The male-dominated environment

(4) in IT courses can make women feel isolated or

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

888

unwelcome: I think what doesn't attract women to this

course is the number of men; they might feel like they

don't belong or don't feel safe, I'm not sure."(PM#34)

Perpetuated stereotypes suggest that women are

better suited for social interaction-oriented fields,

while IT is seen as a logical domain more suited to

men: "Yes, because for women, it's not as attractive;

women are emotional beings, men are

rational/logical, and IT is mostly logical."(PM#36)

Programs like Design and Multimedia show balanced

gender representation, but engineering-focused IT

courses remain male-dominated.

Twenty-three participants believe that there is no

gender difference in receiving support from parents

or society to study IT: "Nowadays, despite the male

presence being dominant, there is, in my view, no

difference between these two genders in terms of

family and/or societal support."(PM#32); "I think

that more and more families don't care about that,

mainly because it's an area considered important

with practically guaranteed employment."(PF#5)

Conversely, seventeen said there is a difference: "Yes,

the IT field is dominated by boys, so it's more likely

for girls to be discouraged from entering these

courses."(PM#9)

4.6 Suggestions

In response to RQ6: What suggestions do students

have for parents, schools, and universities to support

and recruit more underrepresented groups into IT

courses, participants' answers were captured

regarding the following three themes:

Encouragement and Support from Parents, Support

from Schools and Teachers to Help Students Decide

on IT, and Support from Higher Education

Institutions to Attract More Women to IT-related

courses.

Participants suggested ways parents could

encourage their children to pursue IT courses, with

most agreeing on the value of encouragement, though

six believed parents should focus on supporting their

children's decisions instead. Suggestions included

presenting the IT field (15) by demonstrating its

possibilities and facilitating access to technology,

providing early experiences (14) through

extracurricular activities and exposure to technology,

and discussing prospects (8) by emphasizing IT's

career opportunities and importance.

Respondents agreed that schools and teachers

should support students in making decisions about IT

and offered suggestions on how to do

this: "Information sessions about various areas. At

my school, they brought in higher education IT

professors who presented interesting projects

developed."(PF#9); "Show the applicability of IT

areas. Conduct activities in collaboration with

universities. Create boot camps, workshops, and

lectures to allow exploration and contact with these

areas."(PF#19); "Show the applicability of

integrating certain problems into algorithms, etc.,

and show how it can be fun."(PM#9); "Showing what

is possible to do with the knowledge obtained, even

just the basics. Like basic robotics and problems that

can be solved with programming."(PM#21)

Students suggested actions to how higher

education institutions could attract more women to

IT-related courses, such as aligning IT with interests

of young women, conducting awareness campaigns,

and integrating artistic elements with IT to foster

early interest: "Show and relate it to what a girl aged

14-18 likes." (PM#5); "Engage more closely with

young women and explain the reality of working in

this great field and the opportunities it can offer them

for a good living condition in the future."(PM#6);

"Awareness campaigns in high schools."(PF#18)

However, three female participants argued that

efforts should target both genders, promoting IT

generally without focusing exclusively on women, to

avoid seeming condescending. Five male participants

felt that institutions should remain neutral, suggesting

that the choice to pursue IT should be a personal one

and not influenced by gender-focused initiatives.

They believed that social change rather than

institutional action would have a more significant

impact.

5 DISCUSSION

This section discusses and relates the findings to

previous works and their implications. The SCCT

constructs section will highlight key findings

considering the general themes: Prior Experiences,

Social Support, Self-efficacy, and Outcome

Expectations. The Perceptions & Suggestions section

summarises the participants' prominent opinions on

the IT area.

5.1 SCCT Constructs

Analysing the responses on Prior Experiences, the

results indicate that most subjects needed better

experiences with IT classes in school, describing a

less engaging environment focused only on basic use

of computers and office software. The non-mandatory

IT curriculum led to a lack of emphasis on the subject,

with unprepared teachers further decreasing student

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

889

interest. Therefore, for most participants in this study,

previous experiences in school were not the relevant

factor in their decision to take the course. This is like

the findings of Alshahrani et al. (2018), where four

individuals pursued a degree in computer science

even though they had not studied CS in school.

Only nine students were exposed to specific

programming activities before entering higher

education. However, those who were exposed to these

activities said they influenced their decision to choose

an IT course. Similarly, Alshahrani et al. (2018)

demonstrated that some students decided to pursue an

IT-related course after having had experiences with

robotics or programming.

The students elected personal interest, job

prospects and contact and experience with IT and

equipment as the most significant factors influencing

their choice of higher education courses. These

findings are in part in line with McKenzie and

Bennett’s (2022) conclusions that students’

motivation to study IT is driven primarily by intrinsic

interest rather than external factors such as job

prospects; however, in our study, job prospects (14)

were cited almost equally as highly as personal

interest (17).

Regarding Social Support, the results showed that

only eight participants of this study cited the

influence of parents, friends, close people, or teachers

in determining higher education course choices. No

significant differences were observed among sexes.

This corroborates the work of McKenzie and Bennett

(2022), who revealed that social influences from

family and friends did not significantly influence the

choice of study. In contrast, our results differ from the

previous studies (Alshahrani et al., 2018; Tsakissiris

& Grant-Smith, 2021) that found that support from

parents and family members was critical.

One student specifically cited discouragement

from teachers who encouraged her to pursue

healthcare rather than technology. This corroborates

the work of Varma (2010), who found that teachers

rarely encouraged female students to pursue a

computer science course, unlike their male

counterparts, who received implications of

encouragement.

Regarding Self-efficacy beliefs, most students

(male and female) demonstrated confidence in their

ability to complete the higher course; however, only

female students scored the lowest level of confidence.

Likewise, most (male and female) students stated

they had good skills and enjoyed programming,

highlighting their logical reasoning and problem-

solving abilities. However, only male students

indicated having advanced programming skills, again

demonstrating a greater degree of self-confidence

among men. These findings corroborate previous

studies (e.g. Kallia & Sentence, 2018) that indicate

women rated themselves with less confidence than

men.

Most students expressed positive feelings about

being an IT student, such as being happy, well-

rounded, fulfilled, and confident about the future.

They were also satisfied with their choice of higher

education course. Meanwhile, others said they felt

nothing special, ordinary, or sometimes frustrated and

tired.

Regarding Outcome Expectations, most students

gave answers related to employment and salaries,

contribution to society, and personal and professional

success, which can be achieved by pursuing a course

in IT. They mentioned that these expectations of

outcomes may influence students to study IT,

although some said that it depends on the student's

interests or goals.

Most respondents know about IT careers and

think they are equally attractive to both sexes. There

was no response discrepancy between respondents of

different sexes on this point. However, some pointed

out that it depends on the environment, which can be

toxic and harmful for women. Men also raised this

point. Only one female participant disagreed that IT

careers are attractive to women, justifying that men

still dominate this area.

5.2 Perceptions & Suggestions

Respondents emphasized the importance of IT

education in schools, advocating for Digital Literacy,

Information Security, and the teaching of Logic,

Programming, and Robotics. Early exposure to IT is

crucial to demonstrate its integrative utility across all

fields and expand future career possibilities,

potentially directing students towards IT. However,

some believe that IT should be reserved for interested

individuals only. Respondents noted society’s

perception of IT students, highlighting positive traits

such as intelligence and dedication alongside

negative stereotypes such as being antisocial or

having a superiority complex. They discussed the

causes of the gender gap, citing a hostile and

masculine environment, cultural stereotypes, limited

exposure to technology for girls, and stereotypes

about women’s roles. Opinions on support for the IT

study were divided, with half seeing no gender

difference in the family or social support. In contrast,

others noted that girls are often discouraged from IT

and directed towards fields such as healthcare.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

890

The subjects suggested several ways to enhance

and promote the IT field, with a focus on

encouragement and support from parents, schools,

teachers, and higher education institutions. Parents

can encourage their children by introducing them to

IT, providing them with experiences, and discussing

prospects. Many respondents advocated for schools

and teachers to support students’ IT decisions by

demonstrating the applicability of IT and

incorporating IT into pre-university curricula. In

addition, there was support for higher education

institutions to attract more women to IT courses by

promoting initiatives for young women, raising

awareness, creating role models, and implementing

actions that target both genders.

5.3 Implications and Future Research

Despite the significant contributions of this study, it

is crucial to acknowledge its limitations. Using

instruments such as questionnaires may introduce

bias, as they reflect students’ perceptions rather than

their actual behaviours. Furthermore, variability in

participants’ interpretation of questions may further

contribute to data bias. The integrity of self-reported

information cannot be guaranteed, as some responses

were superficial, thus restricting the full

understanding of complex phenomena.

Furthermore, the study's limited sample size

prevents representation of the broader target

population, thus restricting the generalizability of the

results. To increase the robustness and diversity of

responses, subsequent research should involve a

larger cohort of Portuguese students, including those

from various higher education institutions in

Portugal. Employing alternative data collection

methods, such as focus groups and interviews with

participants from specific disciplines, may obtain

more nuanced and direct insights from research

participants.

In future research, we plan to expand the scope of

this study to include a broader audience,

encompassing students from various regions of

Portugal. We plan to incorporate closed-ended

questions to capture better the factors that influence

students’ decisions to pursue IT.

6 CONCLUSION

This study drew constructs from the Social Cognitive

Career Theory, including prior experience, self-

efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support, to

identify factors influencing IT-related course

selections, focusing on gender analysis.

The findings indicate that prior programming

experience, IT/computer exposure, personal interest,

and positive job prospects significantly impact course

selection. In contrast, parents, friends, and teachers'

support appears less influential. School education was

perceived as having a limited role in shaping

participants' decisions to pursue IT careers, with

computer classes often deemed too essential and

uninspiring.

Participants noted that the stereotypical image of

IT students as "nerds" persists within societal views,

but they regard this characterization as outdated

instead of seeing themselves as intelligent and

capable. The gender disparity in the IT field was

attributed to factors such as a male-dominated

atmosphere, which can lead to feelings of isolation or

lack of belonging for women. Nevertheless, students

reported no perceived gender differences in the

parental or societal support received for pursuing IT

studies.

Participants proposed several strategies to

enhance and promote IT to school-aged audiences.

These include increasing encouragement and support

from parents, schools, teachers, and higher education

institutions. Parents can foster interest by introducing

their children to IT, providing practical experiences,

and discussing potential career paths. Many

advocated for schools and teachers to bolster students'

IT inclinations by illustrating its practical

applications and integrating IT into pre-university

curricula. Furthermore, there was a call for higher

education institutions to attract more women to IT

courses by promoting initiatives for young women,

raising awareness, creating role models, and

implementing gender-inclusive actions.

Finally, this study suggests that educators and

policymakers should enhance computing activities

for students, especially girls, to foster interest and

draw them into IT careers. This would thereby enrich

the sector with diverse perspectives and talents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the students who participated in this

study for sharing their insights and time, as well as

the DEI and DEEC of the University of Coimbra and

the ISEC of the Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra.

This work is financed through national funds by FCT

- Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., in the

framework of the Project UIDB/00326/2025 and

UIDP/00326/2025.

Influences on IT-Related Courses Choices: A Gendered Analysis Based on Social Cognitive Career Theory

891

REFERENCES

Alshahrani, A., Ross, I., & Wood, M. I. (2018, August).

Using social cognitive career theory to understand why

students choose to study computer science. In

Proceedings of the 2018 ACM conference on

international computing education research (pp. 205-

214). https://doi.org/10.1145/3230977.3230994

Atiq, Z., & Loui, M. C. (2022). A qualitative study of

emotions experienced by first-year engineering

students during programming tasks. ACM Transactions

on Computing Education (TOCE), 22(3), 1-26.

Atlas.ti. (2024). ATLAS.ti (Version 24) [Computer

software]. Scientific Software Development GmbH.

https://atlasti.com

Babeş-Vroman, M., Nguyen, T. N., & Nguyen, T. D.

(2021). Gender Diversity in Computer Science at a

Large Public R1 Research University: Reporting on a

Self-study. ACM Transactions on Computing

Education (TOCE), 22(2), 1-31.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2),

77-101, DOI: 10.1191/1478088706q p063oa

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2023). Social cognitive career

theory.

DGEEC - República Portuguesa. Estatísticas da Educação.

https://www.dgeec.medu.pt/art/ensino-superior/undefi

ned/undefined/65520ab1455255473193d29b#artigo-6

70e2bb57ef0cadc601a5ea6

Eurostat – Statistics Explained. https://ec.europa.eu/euro

stat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=ICT_specialis

ts_in_employment#ICT_specialists_by_attainment_le

vel_of_education (Access in nov.2024)

Fouad, N. A., Hackett, G., Smith, P. L., Kantamneni, N.,

Fitzpatrick, M., Haag, S., & Spencer, D. (2010).

Barriers and supports for continuing in mathematics

and science: Gender and educational level differences.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 361–373.

Fouad, N. A., & Santana, M. C. (2017). SCCT and

underrepresented populations in STEM fields: Moving

the needle. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(1), 24–39.

https:// doi.org/10.1177/1069072716658324

Kallia, M., & Sentance, S. (2018). Are boys more confident

than girls? The role of calibration and students’ self-

efficacy in programming tasks and computer science. In

Proceedings of the 13th Workshop in Primary and

Secondary Computing Education: WIPSCE '18,

https://doi.org/10.1145/3265757.3265773

Kube, D., Weidlich, J., Kreijns, K., Drachsler, H., 2024.

Addressing gender in stem classrooms: The impact of

gender bias on women scientists’ experiences in higher

education careers in Germany. Educ. Inf. Technol. 1–

28.

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a

unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic

interest, choice, and performance. Journal of

Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/

10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2019). Social cognitive career

theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and

performance models. Journal of Vocational Behavior,

115, Article 103316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.201

9.06.004

Lent, R. W., Lopez, F. G., Sheu, H., & Lopez, A. M. (2011).

Social cognitive predictors of the interests and choices

of computing majors: Applicability to underrepresented

students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 78, 184–192.

Lent, R. W., Sheu, H. B., Miller, M. J., Cusick, M. E., Penn,

L. T., & Truong, N. N. (2018). Predictors of science,

technology, engineering, and mathematics choice

options: A meta-analytic path analysis of the social-

cognitive choice model by gender and race/ethnicity.

Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(1), 17–35.

https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000243

Master, A. H., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2020). Cultural

stereotypes and sense of belonging contribute to gender

gaps in STEM. International Journal of Gender,

Science and Technology, 12, 152-198.

McKenzie, S., & Bennett, D. (2022). Understanding the

career interests of Information Technology (IT)

students: a focus on choice of major and career

aspirations. Education and Information Technologies,

27(9), 12839-12853

Smit, R., Schmid, R., & Robin, N. (2024). Experiencing

enjoyment in visual programming tasks promotes self‐

efficacy and reduces the gender gap. British Journal of

Educational Technology.

Spieler, B., Oates-Indruchovà, L., & Slany, W. (2020).

Female students in computer science education:

Understanding stereotypes, negative impacts, and

positive motivation. Journal of Women and Minorities

in Science and Engineering, 26(5).

The jamovi project (2022). jamovi. (Version 2.3)

[Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.

jamovi.org.

Tsakissiris, J., & Grant-Smith, D. (2021). The influence of

professional identity and self-interest in shaping career

choices in the emerging ICT workforce. International

Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 22(1), 1–15

Varma, R. (2010). Why so few women enroll in computing?

Gender and ethnic differences in students' perception.

Computer Science Education, 20(4), 301-316.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

892