Familiarity Breeds Confidence: Creating Effective Digital Literacy

Resources for Older Adults

Meredith Kellenberger, Sarah Leidich and Dharini Balasubramaniam

a

School of Computer Science, University of St Andrews, North Haugh, St Andrews, U.K.

Keywords:

Digital Literacy, Digital Divide, Older Adults, Ageing.

Abstract:

As population ageing is observed globally, and technology continues to expand into most parts of our lives,

many older adults face challenges in adapting to a world that they feel unprepared to inhabit — one filled

with increasingly intertwined and fast-evolving technologies that have become necessary to fully participate

in society. The age-related digital divide, caused by the gaps in access, motivation and skills of many older

adults to use digital technologies compared to younger people, is now a significant problem for the wellbeing

and independence of older adults and requires urgent solutions. Increasing the digital literacy and confidence

of older adults may help reduce this gap. However, effective strategies for improving digital literacy in later

life must take into account the needs and preferences of older learners. This paper reports on two pilot studies

conducted to create and evaluate prototype digital literacy resources to discover effective forms and content.

This work draws from literature, related work, and feedback on our prototypes from older adults in local

communities. Our findings indicate that older adults often prefer device and task-specific digital literacy

resources in printed form as a familiar medium before progressing to digital learning, and value community

involvement in ongoing support for the learning process. Resources that use figure-of-speech based language

and informative diagrams can also be beneficial to older adults, particularly when learning novel digital tasks.

These preliminary insights also highlight the potential for conflicting requirements from a diverse demographic

and the need for further exploration of the topic.

1 INTRODUCTION

The interconnected and rapid expansion of technolo-

gies in most sectors has the potential to increase op-

portunities, open avenues for digital exploration and

education, lead to advances in many disciplines, al-

low for global connections and make our lives more

interactive, entertaining and convenient. Many peo-

ple around the world reap these benefits. However,

this digitalisation has also created a divide. Some

marginalised groups are unable to take advantage of,

or are even actively disadvantaged by, the rapidly ex-

panding and evolving digital landscape, which be-

comes frustrating and intimidating. This is particu-

larly true for many older adults, who are now facing

a significant challenge: learn to adapt to the digital

world or be left behind.

Older adults often face significant barriers to

achieving the digital literacy required to engage with

the digital world. Many have low confidence in their

ability to understand and use technology (Berkowsky

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5093-0906

et al., 2017), a fear of making mistakes they cannot

recover from (Sandhu et al., 2013; Atkinson et al.,

2016; K

¨

ottl et al., 2021), and internalised ageism that

colours their perception of their abilities (Zhao et al.,

2023; K

¨

ottl et al., 2021). As two of the participants in

our studies commented,

”There’s always a little confidence thing

somewhere...[asking myself] ’am I getting this

right?’. Because I don’t think I’m very good at

it...I was never taught. There’s that confidence

thing always. Something missing in what I’m

doing.”

”Maybe it’s my age but I find that being

walked through something once, I don’t retain

it as well now. Whether it has become more

complex, I think there’s two sides to it. One I

think the world has become more complex and

dependent on systems and technology and the

other is obviously the personal aging thing,

where maybe I’m not as quick as I used to be”

These and other barriers, such as socioeconomic

status (Hargittai et al., 2019), may reduce older

284

Kellenberger, M., Leidich, S. and Balasubramaniam, D.

Familiarity Breeds Confidence: Creating Effective Digital Literacy Resources for Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0013299000003938

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 284-290

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

adults’ motivation for learning, and contribute to the

widening ‘digital divide’, a divide between those who

have access to and use of information and communi-

cation technologies and those who do not (Van Dijk,

2020). This knowledge and access gap means that

older adults often feel anxious and isolated as the

world digitalises around them.

An AgeUK briefing from June 2024 found that 1.7

million people in the UK aged 75 and over do not use

the internet (AgeUK, 2024). 49% of people over 75,

and 37% of people over 65 cannot complete all tasks

in the Essential Digital Skills framework

1

created by

the Department for Education, which categorises dig-

ital skills related to handling information, transact-

ing, communicating and operating online safely and

legally. 33% of those over 75 and 13% over 65 do

not have the digital skills needed to thrive in a digital

society.

These issues are not present in the United King-

dom alone, but represent a global phenomenon (UN-

HABITAT, 2021), with a larger gap between devel-

oped and developing regions of the world, and Africa

facing the largest gap. 27% percent of adults 65 and

over in the United States are still offline (Xie et al.,

2021). 94%-98% of younger adults aged 18-44 reg-

ularly use the internet in Australia, compared to just

51% of those 65 and older (Tyler et al., 2020). In

many developed countries, the demographic of people

aged 64 and over is the fastest growing group, and yet

their use of Information and Communication Tech-

nologies trails behind younger demographics (Neves

et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2021). It is projected that peo-

ple over age 60 will outnumber children under age 10

for the first time in history by 2030 (Tyler et al., 2020).

One critical way to decrease loneliness and isola-

tion in older adults related to the rapid digitalisation

of day-to-day tasks is through improving their digital

literacy. The aim of the studies reported in this pa-

per was to explore effective types and styles of digital

literacy resources to help bridge the digital divide and

help older adults become more confident in using dig-

ital technologies. As one participant noted,

”The people who need this the most are living

right now”.

Our objectives were to review the literature on

the concepts and related work on digital barriers for

older adults, develop customised prototype resources

to overcome the barriers, and evaluate their effective-

ness through user studies with older adults in the lo-

cal community. Two small scale user studies were

conducted and data from these studies were analysed.

1

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/essential-

digital-skills-framework/essential-digital-skills-framework

Findings from this evaluation suggest that accessible

and engaging digital literacy resources are helpful to

older adults. However, they also indicate that there is

much variation in learning styles and preferences of

older adults. Further research and larger studies are

required to address the challenge.

The remainder of this paper is organised as fol-

lows. Section 2 provides a brief review of related

work in the area. Section 3 outlines the methodology

adopted for the studies. Section 4 describes the proto-

type resources produced as part of the work. Section

5 explains the evaluation process and presents the re-

sults. Section 6 outlines the limitations of the work.

We offer conclusions and recommendations for future

work in Section 7.

2 RELATED WORK

The digital divide mentioned earlier can impact both

access to and effective use of technology (Riggins and

Dewan, 2005). The first level digital divide relates to

a lack of access to digital technologies due to factors

such as cost and unavailability, while the second level

divide relates to factors such as lack of motivation,

digital literacy and support, even when the first level

divide does not apply (Van Dijk, 2020).

In this paper, we adopt a broad definition of the

term digital literacy as literacy in the digital age

(Gilster, 1997) – an essential life skill that includes

the ability to understand and use digital technologies

appropriately, learn new skills, and deal with errors

without losing confidence. Digital literacy extends

beyond basic technology proficiency, encompassing

complex skills such as information literacy and real-

time thinking (Eshet-Alkalai, 2012).

Current digital literacy solutions for older adults

include one-to-one trainings (Boulton-Lewis et al.,

2007)) and peer-to-peer learning (Piercy, 2019).

However, obstacles such as anxiety, fear of online

dangers, and physical limitations (Steelman et al.,

2016; Czaja and Sharit, 2012) remain. Literature

shows that older adults prefer a combination of self-

regulated and guided learning (Schlomann et al.,

2022) and that lessons must be relevant to their

needs. Moreover, they prefer to learn in informal,

knowledge-sharing environments, which can be bene-

ficial for older adults as it can promote relaxation and

collaboration, and reduce feelings of being a burden

to family and friends who support them in learning

digital skills.

Many technology, public sector and charitable or-

ganisations produce digital guidance resources, some

of which are aimed at older adults. However, these

Familiarity Breeds Confidence: Creating Effective Digital Literacy Resources for Older Adults

285

resources are not typically customised to the specific

needs of older adults, and where in-person support is

offered, they do not scale well with demand.

While universal design principles offer guidance

on accessible resources (Centre for Excellence in Uni-

versal Design, nd), a gap remains in research on tai-

lored, community-integrated digital literacy resources

for older adults. This study aims to address this gap

by exploring, developing and evaluating prototype

customised resources.

Literature suggests that metaphors and figures-of-

speech can be beneficial in shaping our mental mod-

els when learning new material. Lakoff and Johnson

define metaphors as “understanding and experiencing

one kind of thing in terms of another” (Lajoff and

Johnson, 2003). Experts in educational theory, lin-

guistics and other related fields have suggested “mak-

ing and remaking reality with our minds” through

metaphor is one way people make sense of and learn

about their environments (Cook-Sather, 2003). The

novelty of our work is in exploring how digital tech-

nologies may be explained in terms of familiar con-

cepts and presented in familiar ways that help create

useful mental models.

3 METHODOLOGY

The work reported in this paper was conducted over a

period of around 3 months. Two sets of digital literacy

resources were created based on research on the sub-

ject content, the needs of older adults as ascertained

from literature and prior work, and general accessi-

bility guidelines. We aimed to create different kinds

of resources to illustrate a few possible options for di-

mensions such as the format of the resource and level

of detail.

Two small scale but in depth studies (A and B)

were conducted. Ethics permission for both was ob-

tained from the authors’ institution. In both cases,

participants were recruited through advertisements in

local community spaces and personal contacts. We

considered anyone 60 years or older as an older adult.

We are aware that there are differing thresholds in lit-

erature for being considered older. For the purposes

of these studies, the 60+ threshold allowed us to re-

cruit participants from a broad range. The surveys

and the activities were based on the Essential Digital

Skills framework mentioned earlier.

In Study A, a set of digital literacy resources were

designed with a focus on simplification, accessibil-

ity, device and application specificity, and universal

design principles (Centre for Excellence in Univer-

sal Design, nd). The resources included a glossary of

icons, terms and definitions, and guides for everyday

digital tasks. To evaluate the effectiveness of these re-

sources, user studies were conducted with four partic-

ipants from the local community. Their ages ranged

from early sixties to late seventies. There were three

women and one man.

The evaluation process involved pre-activity sur-

veys to ascertain initial digital literacy levels, fol-

lowed by participants reviewing the resources and

attempting a digital task. Post-activity surveys and

feedback sessions were then conducted to gauge per-

ception of improvements in digital literacy and gather

insights on the effectiveness of resources. This ap-

proach allowed for both quantitative and qualitative

assessment of the impact of the resources on older

adults’ digital literacy and confidence. However, with

the small sample, the quantitative measure is not

treated as significant.

Study B was a qualitative study comparing re-

source and language preferences of seven older adults

with ages ranging from early sixties to late eighties.

Five participants were from the local area, and two

from farther afield. There were three women and four

men.

Participants were given prototype resources in dif-

ferent formats, and asked to complete three digital

tasks on high-fidelity recreations of several websites

using the prototype resources. They were observed

as they undertook the tasks, and were then given ad-

ditional non-task related resources to review. Af-

terwards, a semi-structured interview was conducted

with each participant on their experiences in learning

to complete digital tasks, their preferences for digi-

tal literacy resources and use of figure-of-speech lan-

guage. They were also given the opportunity to pro-

vide feedback on the additional resources provided.

Thematic analyses of the two sets of responses

were conducted to identify patterns and themes in re-

sponses to arrive at findings and avenues for further

work.

4 DIGITAL LITERACY

RESOURCES

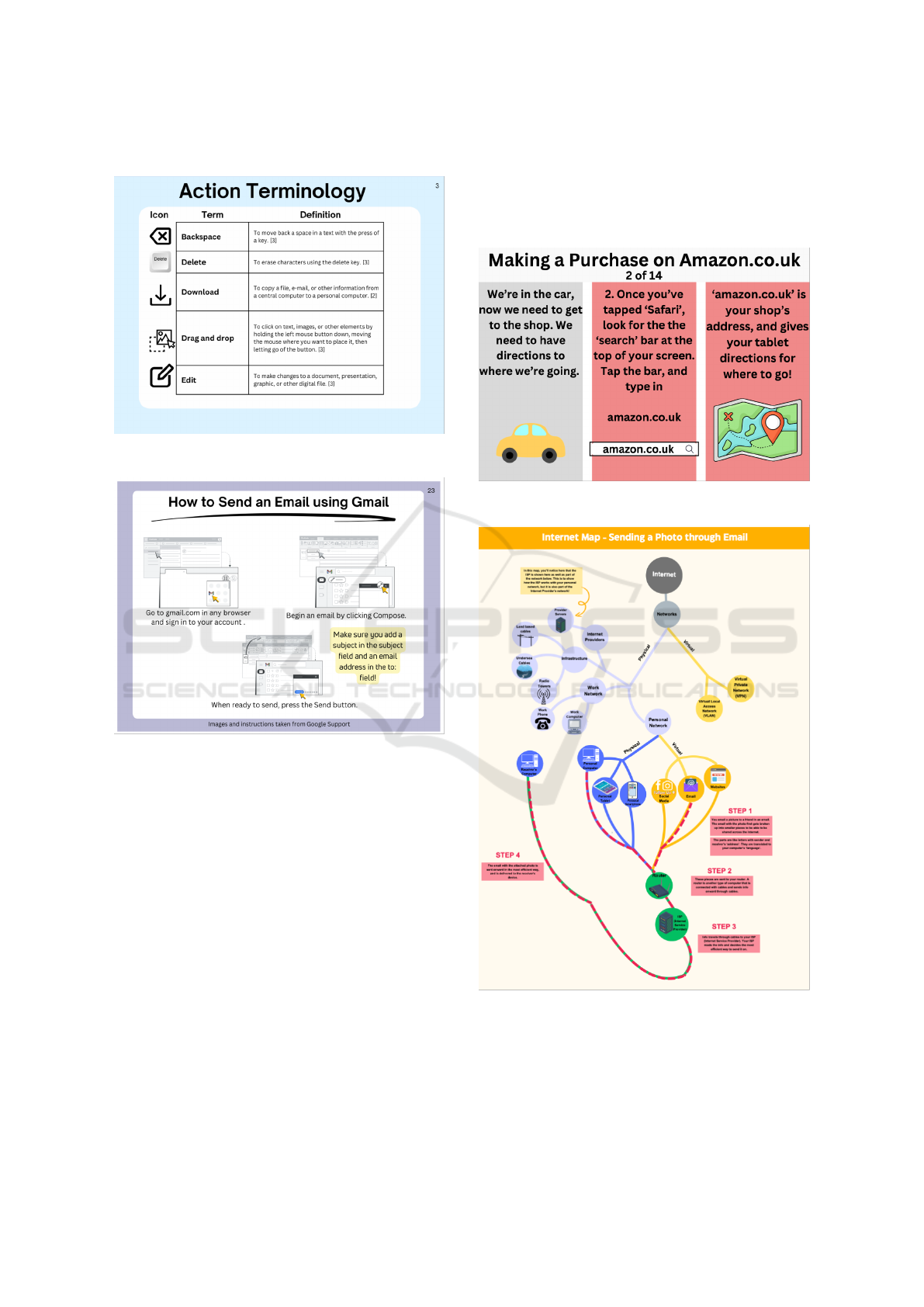

The resources developed in Study A consisted of a

glossary (a subset shown in Figure 1) and instruc-

tional guides (a high level version shown in Figure

2). The glossary provided clear definitions of digital

terms and concepts, while the guides offered step-by-

step instructions for specific tasks such as putting a

smartphone into Airplane mode and sending emails.

These were designed with large fonts and simple lay-

outs for accessibility, and were made available in both

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

286

printed and digital formats.

Figure 1: Explanation of action icons.

Figure 2: Illustrated instructions for specific software.

The resources developed for Study B comprised

one video-based and multiple printed resources with

and without figure-of-speech language, illustrations,

and demonstration. Three resources were related to

specific tasks and additional resources were created

for review unrelated to a task. The first resource was

a step-by-step resource with minimal text which in-

cluded no illustrations or figure-of speech language,

one resource used illustrations and figure-of-speech

explanations alongside step-by-step instruction (one

step shown in Figure 3), and one video resource

demonstrated the task while also instructing partic-

ipants on the task using figure-of-speech explana-

tions. The non-task related resources included a refer-

ence resource structured as a mind-map providing the

names of common platforms used for different inter-

net tasks such as streaming, social media, and search-

ing for information, a text-based “cheat sheet” chart

for online safety including information on viruses,

and website and email scams, and an internet structure

diagram (Figure 4) showing a task, namely sending a

photo attachment in an email, in the context of the

overall structure of the internet, illustrating the ‘jour-

ney’ of the email as it is sent and received.

Figure 3: Shopping analogy.

Figure 4: Mental model of email working over the internet.

Familiarity Breeds Confidence: Creating Effective Digital Literacy Resources for Older Adults

287

5 EVALUATION

All user studies were conducted in a one-to-one set-

ting.

The evaluation process for Study A involved pre-

activity surveys to assess initial digital literacy, fol-

lowed by participants reviewing the developed re-

sources and attempting a digital task. Post-activity

surveys and feedback sessions were then conducted.

The pre-activity survey gathered data on partici-

pants’ use of digital services, device ownership, con-

fidence in using digital technologies and challenges

faced when doing so. All participants owned smart-

phones, 3 owned tablets and desktops as well and 2

had laptops. All participants used their devices for

email and online shopping, while some had attempted

online banking and booking appointments. Partici-

pants were very interested in digital technologies, and

had engaged with them but also experienced chal-

lenges in using them and frustration regarding inad-

equate support and inaccessible language used.

The post-activity survey attempted to assess the

effectiveness of the resources in improving digital lit-

eracy, alignment of the resources with preferences and

learning styles of older adults and the aspects of the

resources that were most helpful and that needed im-

provements.

Results showed increased motivation among par-

ticipants to continue learning about digital tech-

nologies, with all participants rating the resources

as highly clear. Participants also provided valu-

able feedback, suggesting the need for more device-

specific guides and highlighting the importance of

community-based training sessions to complement

the resources. The importance of a support network

was a recurring theme.

The evaluation of resources in Study B were solely

qualitative. Participants were observed using and re-

viewing the resources, and all participants were inter-

viewed using a semi-structured format directly after

finishing the three tasks. The tasks involved making

a travel booking, online shopping and searching the

web using high-fidelity recreations of the real web-

sites using the resources provided. During the pro-

cess, it was noted that participants who were already

familiar with a task tended to ignore the resources un-

til confronted with a problem and that some partic-

ipants instinctively attempted to book travel to their

own destination or look for items they would nor-

mally purchase, rather than the values we specified

for the tasks. In contrast, one person watched the in-

structional video all the way through and immediately

applied the learning to the task of web search.

The interview questions addressed the challenges

participants faced when trying to learn new digital

skills, their views on potential solutions to these chal-

lenges, preferences among the types of resources pro-

vided, and suggestions for other helpful digital liter-

acy resources.

The challenges mentioned by participants in-

cluded unfamiliar terminology, the need to deal with

new devices or updates to existing software and de-

vices, lack of self confidence, memory issues and the

volume of information that had to be remembered.

Most participants stated they preferred printed,

task-orientated resources that used images and did not

have overwhelming amounts of text. Printed mate-

rials provided reassurance to participants when they

were unsure. As one participant pointed out,

”I found myself printing off the instructions

so I have them to keep. I’m maybe still of the

generation that finds some printed material is

reassuring...at any point I can refer to a page

and it’s just that page. I really don’t need the

whole thing again.”

The size of font, use of contrasting colours and vi-

sual representations, and pace and level of detail in

the instructions were factors that impacted the effec-

tiveness of resources. Participants on the younger end

of the age range preferred the video resource, but also

liked to use printed resources. Older participants ad-

ditionally preferred figure-of-speech based resources.

No participants found the internet structure diagram

resource helpful, although most mentioned it could be

useful if they were interested in learning more specif-

ically about the internet. All participants stated they

did not care to understand the mechanics of complet-

ing digital tasks as long as they could complete steps

to accomplish the task.

All participants thought the task-based resources

were helpful and clear, with younger participants be-

lieving them to be over-explained, and older partic-

ipants preferring more explanation to less. All par-

ticipants agreed that clearly and thoroughly explained

resources would be helpful regardless of age if they

were attempting a novel task.

6 LIMITATIONS

Both studies described in the paper were small scale

and mainly, but not solely, focused on one geographic

area. Most of our participants owned a smart device

and had some experience with digital technologies.

Although we attempted to recruit participants through

diverse channels, the results are not likely to be repre-

sentative of a large demographic that is increasing in

size and experiencing different levels and extents of

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

288

the digital divide. However, even with this small sam-

ple, the results are interesting in the differences they

highlight.

To minimise any anxiety related to taking part

in studies related to digital technologies, participants

were asked to provide their own assessment of their

digital literacy levels through a survey prior to review-

ing our resources and their perception of changes af-

terwards. These data may not accurately reflect their

true digital literacy, confidence and improvements as

a result of using the resources.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

Our participants were generally very interested in

learning about digital technologies and acknowledged

the inevitable move towards a digital-by-default soci-

ety. One participant said,

”It’s omnipresent. You can’t get away from it.

It’s part of our daily lives and if you want to

participate, you need to manage that informa-

tion source”

At the same time, there was frustration regarding

the inaccessibility of everyday technologies and lack

of support. One person explained,

”For instance, I couldn’t figure out how to turn

the computer back on in my car. It was say-

ing something it never said before, so I had to

take out the book to read how to fix it, but I

couldn’t go from the book to the screen. I had

to take my iPad, look up what it was telling

me, and then try to do it on the car app. I

couldn’t remember, when I closed the screen,

what to do, so I also had to use my phone. It

was very confusing, and it took me two and a

half hours”

Our current and prior studies (Vaswani et al.,

2023; Farag et al., 2024) as well as the literature out-

lined in Section 2 highlight the need for research in

improving the digital literacy and digital inclusion of

older adults. An overarching theme of our work is the

importance of consistency and the resulting familiar-

ity in facilitating the use of digital technologies and

boosting confidence.

Findings from Study A suggest that engaging re-

sources can effectively improve digital literacy among

older adults, but customisation and community inte-

gration are crucial for success. Key recommenda-

tions include developing device-specific guides, im-

plementing community-led training sessions, and of-

fering regular, ongoing support. Future work should

focus on expanding the sample size to improve un-

derstanding of additional dimensions of accessibility,

conducting long-term impact studies to assess reten-

tion of digital skills, and collaborating with local or-

ganisations to integrate these resources into existing

community programs. Additionally, exploring the po-

tential for digital platforms to complement and follow

printed materials could enhance the accessibility and

reach of these resources, while addressing the evolv-

ing needs of older adults in an increasingly digital

world.

Study B indicates that most older adults could pre-

fer printed resources that are specific to their needs,

with thorough explanations and definitions. Feed-

back shows that, when creating printed digital lit-

eracy resources, the inclusion of diagrams and im-

ages, colour-coding, increasing font size and min-

imising large blocks of text are beneficial. Figure-

of-speech based language was found to be helpful,

particularly for the oldest participants, and for novel

tasks. Resources with structures such as mind maps

were thought to be helpful in some digital literacy

contexts, but these were limited as participants felt

they did not always give enough information. Addi-

tionally, care should be taken in creating resources so

they are not over-explained, which could make older

adults feel ignorant or insulted.

Findings suggest that a mechanism to generate

custom resources based on the digital task, resource

preferences and skill level of individuals would be

beneficial for older adults who struggle to find re-

sources that work well for their needs and fully ad-

dress their questions. As Study B did not collect

any quantitative data, future work is needed to deter-

mine the actual efficacy of older adults’ preferred re-

sources, and whether the use of figure-of-speech lan-

guage decreases error rates, completion times, and in-

creases older adults’ ability to recall and complete the

task again without a resource.

Even within these small groups of participants,

differences in attitudes, needs and preferences were

observed with respect to depth of explanation, for-

mat of resources, and means of support. Our find-

ings indicate that there is need and scope for exten-

sive future work, including co-creating instructions

and other reference resources with older adults, in-

vestigating the implications of language and linguistic

features in creating accessible resources, and explor-

ing in depth the potentially conflicting needs of indi-

viduals and ways of reconciling them. Scalability and

sustainability as applied to digital literacy resources

(given the preference for printed material), their dis-

semination, coordinating support from peers and or-

ganisations, and facilitating a transition from famil-

Familiarity Breeds Confidence: Creating Effective Digital Literacy Resources for Older Adults

289

iar printed material to online resources are particular

challenges for the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contri-

butions of all the participants in our studies.

REFERENCES

AgeUK (2024). Facts and figures about digital inclusion

and older people. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/siteasset

s/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-b

riefings/active-communities/internet-use-statistics-j

une-2024.pdf. Accessed: 18 November 2024.

Atkinson, K., Barnes, J., Albee, J., Anttila, P., Haataja, J.,

Nanavati, K., Steelman, K., and Wallace, C. (2016).

Breaking barriers to digital literacy: An intergenera-

tional social-cognitive approach. In Proceedings of

the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference

on Computers and Accessibility, pages 239–244.

Berkowsky, R. W., Sharit, J., and Czaja, S. J. (2017). Fac-

tors predicting decisions about technology adoption

among older adults. Innovation in aging, 1(3):igy002.

Boulton-Lewis, G. M., Buys, L., Lovie-Kitchin, J., Barnett,

K., and David, L. N. (2007). Ageing, learning, and

computer technology in australia. Educational Geron-

tology, 33(3):253–270.

Centre for Excellence in Universal Design (n.d.). The 7

principles. https://universaldesign.ie/about-univers

al-design/the-7-principles. Accessed: 18 November

2024.

Cook-Sather, A. (2003). Movements of mind: The matrix,

metaphors, and re-imagining education. Teachers col-

lege record, 105(6):946–977.

Czaja, S. J. and Sharit, J. (2012). Designing Training and

Instructional Programs for Older Adults. CRC Press.

Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A

revised model for digital literacy. Issues in Informing

Science and Information Technology, 9:267–276.

Farag, Y., Narra, G., Balasubramaniam, D., and Boyd,

K. (2024). Improving the digital literacy and so-

cial participation of older adults: An inclusive plat-

form that fosters intergenerational learning. In Pro-

ceedings of the 10th International Conference on In-

formation and Communication Technologies for Age-

ing Well and e-Health - ICT4AWE, pages 47–58. IN-

STICC, SciTePress.

Gilster, P. (1997). Digital Literacy. John Wiley and Sons.

Hargittai, E., Piper, A. M., and Morris, M. R. (2019). From

internet access to internet skills: digital inequality

among older adults. Universal Access in the Infor-

mation Society, 18:881–890.

K

¨

ottl, H., Gallistl, V., Rohner, R., and Ayalon, L. (2021).

“but at the age of 85? forget it!”: Internalized ageism,

a barrier to technology use. Journal of Aging Studies,

59:100971.

Lajoff, G. and Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by.

The University of Chicago Press.

Neves, B. B., Amaro, F., and Fonseca, J. R. (2013). Com-

ing of (old) age in the digital age: Ict usage and non-

usage among older adults. Sociological research on-

line, 18(2):22–35.

Piercy, L. (2019). Designing digital skills interventions for

older people. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/ asset

s/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/Designin

g-digital-skills-interventions-for-older-people.pdf.

Accessed: 18 November 2024.

Riggins, F. J. and Dewan, S. (2005). The digital divide:

Current and future research directions. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 6.

Sandhu, J., Damodaran, L., and Ramondt, L. (2013). Ict

skills acquisition by older people: Motivations for

learning and barriers to progression. International

Journal of Education and Ageing, 3(1):25–42.

Schlomann, A., Even, C., and Hammann, T. (2022).

How older adults learn ict—guided and self-regulated

learning in individuals with and without disabilities.

Frontiers in Computer Science, 3:803740.

Steelman, K. S., Tislar, K. L., Ureel, L. C., and Wallace, C.

(2016). Breaking digital barriers: A social-cognitive

approach to improving digital literacy in older adults.

In Stephanidis, C., editor, HCI International 2016 –

Posters’ Extended Abstracts, pages 445–450, Cham.

Springer International Publishing.

Tyler, M., De George-Walker, L., and Simic, V. (2020). Mo-

tivation matters: Older adults and information com-

munication technologies. Studies in the Education of

Adults, 52(2):175–194.

UN-HABITAT (2021). Assessing the digital divide. https:

//unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2021/11/assessing t

he digital divide.pdf. Accessed: 18 November 2024.

Van Dijk, J. (2020). The digital divide. John Wiley & Sons.

Vaswani, M., Balasubramaniam, D., and Boyd, K. (2023).

A novel approach to improving the digital literacy of

older adults. In 2023 IEEE/ACM 45th International

Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engi-

neering in Society (ICSE-SEIS), pages 169–174.

Xie, B., Charness, N., Fingerman, K., Kaye, J., Kim, M. T.,

and Khurshid, A. (2021). When going digital becomes

a necessity: Ensuring older adults’ needs for informa-

tion, services, and social inclusion during covid-19. In

Older Adults and COVID-19, pages 181–191. Rout-

ledge.

Zhao, Y., Zhang, T., Dasgupta, R. K., and Xia, R. (2023).

Narrowing the age-based digital divide: Developing

digital capability through social activities. Informa-

tion Systems Journal, 33(2):268–298.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

290