Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours

and Strategies

Burak Merdenyan

a

and Helen Petrie

b

Department of Computer Science, University of York, Heslington East, York, U.K.

Keywords: Authentication, Passwords, Older People, Young People.

Abstract: Many aspects of life are now conducted online, and many services requiring a secure account, usually

password protected. Creating and tracking many online accounts and passwords is difficult for everyone. For

older people it may be particularly problematic but vitally important as online accounts now give access to

many healthcare, financial and support services. This study used an online questionnaire to investigate the

behaviours, problems, and strategies in relation creating and using password-protected online accounts with

a sample of 75 older UK participants (aged 65 to 89) and compare them with a similar sample of young UK

participants (aged 18 to 30). The results were surprising, with unexpected differences between the groups, but

many similarities. For example, older participants had no difficulties creating passwords of the right length,

whereas young participants had difficulties in that task. Older participants had many more complex strategies

for creating and remembering passwords, while young participants relied more on re-using old passwords

with small changes which then probably caused difficulties remembering them. These results suggest we need

to rethink the approach to better supporting older people in password creation and use, taking a more universal

design approach, supporting all users with a range of options.

1 INTRODUCTION

Increasingly more and more aspects of life are

conducted online, from making an appointment with

one’s doctor to paying an electricity bill to booking a

cinema ticket to paying for groceries (and arranging

to have them delivered). Many of these services

require having a secure online account, most often

password protected. Creating and keeping track of

many online accounts and passwords is difficult for

everyone, but for older people it may be particularly

problematic. Using online systems may be something

they are not familiar and comfortable with, and they

may have more issues with creating and remembering

passwords than younger people. However, much of

the research in this area is based on a rather superficial

reading of the research literature on aging. But using

online systems is becoming increasingly important

for older people, particularly those living in the

community, to be able to access important services

such as health care, thus it is particularly important to

design password systems that meet their needs.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6268-5090

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0100-9846

Therefore, this study set out to investigate the

problems and password behaviours of older people

and whether they differ from those of younger people

by reviewing previous research and conducting a

study which compares people’s reports of their

behaviours, problems, and strategies with passwords

in two UK samples, one aged 18 to 30 years and the

other 65 years and older. The sample of older people

are those living independently in the community who

need to manage their own online accounts.

2 RELATED WORK

There is a considerable body of research on the needs

of people with different disabilities in relation to

authentication and passwords (for overviews see

Andrew et al., 2020; Furnell, Helkala & Woods,

2021; Petrie & Schmeelk, 2024). In addition, there

has been considerable work on solutions to address

the problems people with disabilities encounter,

particularly the development of auditory alternatives

78

Merdenyan, B. and Petrie, H.

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies.

DOI: 10.5220/0013299800003938

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 78-91

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

to CAPTCHAs (Completely Automated

Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans

Apart) for people with visual disabilities (e.g. Alnfiai,

2020; Fanelle et al., 2020; Holman et al., 2007, 2008;

Lazar et al., 2012; Sauer et al., 2010). Some of the

problems highlighted for disabled people may also be

experienced by older people. For example,

approximately 80% of those with visual disabilities

are 65 and older (RNIB, 2024), so some of the

problems experienced by visually disabled people

may well be experienced by older people. In addition,

some of the solutions developed for disabled groups

(e.g. alternatives to visual CAPTCHAs) may assist

older people.

However, there is only a small body of research

directly investigating the needs and problems of older

people in this area. Indeed, numerous papers

proposing solutions for older people in relation to

passwords and authentication do so only on the basis

of received knowledge about their problems or a

rather superficial reading of the research literature on

aging, and emphasise physical and cognitive decline.

But the research often fails to consider either the

timeline of these declines (which are typically not

substantial until after the age of 75) or the lived

experience of older people. For example, they may

have more time than young people to consider issues

such as how to create passwords, they may have

developed strategies for remembering information in

other areas that they can apply to remembering their

passwords and they may be more concerned about

online security and prepared to put more effort into

creating and managing passwords.

The earliest research which could be identified

which investigated older people’s use of and memory

for passwords appears to a study by Pilar et al. (2012)

in Brazil. 263 participants in three ages groups (18 –

39 years: 91 participants; 40 – 64 years: 100

participants; and 65 – 93 years: 72 participants) were

interviewed about their passwords, using a protocol

developed by Brown et al. (2004). Participants were

asked to provide the length and composition of all

their passwords, but not to reveal their actual

passwords in order to protect their security, and they

were also asked whether they ever forgot or confused

any of these passwords. Pilar et al. found that it was

the number of different circumstances in which

passwords were used rather than participants’ age

which predicted forgetting and confusing passwords.

Carter (2015, see also Carter et al., 2017)

interviewed 20 people over the age of 60 in the USA

as a preliminary to developing a graphical password

system suitable for older people, with 15 of the

participants interviewed in greater depth. The results

of both types of interviews are only briefly described,

although the researchers state that participants were

asked about password creation, management and

recall. Eleven of the 15 interviewed in depth reported

that they used a password creation strategy based on

familiar components such as a child’s name, previous

phone number, pet name, or spouse’s birthdate. It was

reported that none of the participants used strong

passwords which included upper- and lower-case

letters, numbers, and symbols, but no explanation is

given of how this was determined. Thirteen of the 15

participants reported that they normally wrote down

their passwords.

Ahmed et al. (2017) interviewed 25 people aged

between 50 and 90 (50 is a very young starting age

for older people) in the USA, again with a very brief

description of results. The questions appear to have

been oriented to a biometric authentication

system for

older people which the authors were testing. They

reported that 72.2% of the participants felt that typing

in passwords took a rather long time, but only 61.1%

of older adults preferred the idea of biometric

authentication (it is not stated whether any of the

participants had used biometric authentication before

the study or whether this attitude was a reaction to the

system in the study).

Renaud et al. (2018) present three personas of

older people (i.e. fictional descriptions which should

be based on a body of evidence and research, Nielsen,

2024) with the kinds of issues they might have with

authentication. It is good that they are all considerably

old individuals (75, 81 and 90), and the problems

presented may be those encountered by some older

people, but no evidence or research is presented to

substantiate them.

Mentis et al. (2019) conducted interviews with six

older people in the USA with mild cognitive

disabilities, for example the early stages of

neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s

disease and other forms of dementia. Each person was

interviewed with a family member who was caring

for them, as the carers often helped with online issues

such as authentication This study provides very good

insight into the needs of this particular group of older

people, but it only represents one segment of the older

population. Interestingly, the participants were all

still undertaking online activities such as gaming,

video conferencing with family members, using

social media to keep in touch with grandchildren,

purchasing products online, and viewing their online

banking statements. However, they did encounter

problems related to their developing cognitive

disabilities, such as reacting to obviously spam email,

making inappropriate online purchases (buying five

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

79

pairs of shoes when they only intended to buy one

pair), or reacting to or sharing something on social

media in an out-of-character manner. The only

problem related specifically to password use was the

need to share passwords with a trusted carer while

still able to do so, something which older people may

need to plan for.

Morrison et al. (2021) conducted another

interesting and in-depth study with older people, but

like the Mentis et al. (2019) study, one which

provides only tangentially useful information. They

used a card sort and interview process with 19 older

people in the UK, aged 62 to 78 years, about their

protective cyber-security actions and identified the

factors that impact their confidence in carrying out

those actions. They found that the participants were

keen to protect themselves in relation to online

security, but they lacked the appropriate support to do

so. The findings remain at a rather general level in

terms of cyber-security actions, although there is a

brief discussion of the older people’s concerns about

making passwords strong enough.

Ray et al. (2021) tackled the specific issue of

password managers (also discussed in Morrison et al.,

2021) and why older people use these systems or not

to help remember and manage passwords, although

the results also include some interesting observations

about their general password use. They interviewed

26 people over the age of 60 in the USA, a mixture of

those who use stand-alone password managers, those

who use features in the browser or operating system

to manage their passwords and those who use none of

these options, so no digital password memory

support. They based their work on a study by Pearson

et al. (2019) which studied the same issues with the

same groups of participants, but with participants

aged under 60. The three groups of participants

reported using different strategies to create

passwords. Non-password manager users tended to

use phrases and words of personal significance.

Participants using browser/operating system

password features tended to follow a specific pattern,

consisting of a set of characters or numbers which

they would move around to generate passwords.

Stand-alone password manager users generally used

a completely random set of numbers and letters, often

created by their password managers. Most non-

password manager users reported creating distinct

passwords, and they rarely reused passwords. The

exception was for accounts termed "casual," where

there were instances of “repurposing” or generating a

password with roots in an older password. Some

participants in both of the password manager using

groups shared this behaviour, admitting that

passwords for less important accounts shared

similarities but more important accounts passwords

were always distinct.

Juozapavičius et al. (2022) took a very different

approach to understanding older people’s problems

with passwords, not working directly with older

people, but studying a leaked database of 102,120

online accounts in Lithuania, which included

encrypted passwords and some demographic

information about the account owners. These were

accounts for an online car sharing scheme, so one

would assume

that users would want at least moderate

protection of the information in their accounts. The

leaked information allowed the researchers to analyse

the passwords for gender and age differences in their

composition. Password complexity decreased

significantly with age for both genders. Overall, very

weak passwords were used, 72% of users based their

password on a word or used a simple sequence of

digits, and passwords of over 39% of users were

found in word lists of previous leaked databases.

Petrie et al. (2022) conducted an online survey of

older people in the UK and China to compare the

problems encountered by older people in two very

different cultures. There were differences between the

two countries in older people’s problems in creating

passwords, but few differences between the two

countries in problems of managing passwords. Both

Chinese and UK participants used poor strategies for

creating passwords. Over half the Chinese

participants reported using familiar dates or numbers,

although only about a third reused passwords exactly

and fewer re-used passwords with small changes.

Whereas over half the UK participants reused

passwords with small changes but were less likely to

use other poor strategies. These results suggested that

older people need more support in creating strong

passwords. On the other hand, participants in neither

country reported major problems in remembering

their passwords.

Several studies have specifically investigated

whether people of different ages share their

passwords with others, potentially an unsafe practice,

but important for older people in some circumstances.

Both Whitty et al. (2015) in the UK and Yuan et al.

(2024) in the USA found that younger people were

more likely to share their passwords with others than

older people. However, when presented with a

hypothetical emergency situation, Yuan et al. found

that older people were more likely to be willing to

share their password than younger people.

Several studies have also taken a more

experimental approach to older people’s use of

passwords. Nicholson et al. (2013a & b) investigated

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

80

whether two different forms of graphical password

(either based on images or on faces) were more

effective for older people in the UK when compared

with a PIN (personal identification number). It is not

clear why they did not compare with the much more

widely used text/number/special symbol passwords,

but this may have been due to experimental control

issues. They found that older participants were most

effective, as measured by accuracy, with a graphical

password based on faces, particularly if age

appropriate faces were used. Vu & Hill (2013) found

similar results with older people in the USA.

As can be seen from this brief review, the research

on what problems older people have with creating and

managing passwords is rather scant, with studies

often having small numbers of participants and results

which are often tangential to the key issues.

A number of solutions have also been proposed to

make password use easier for older people. These

include using graphical passwords to reduce the

cognitive load of remembering passwords including

adapting them with age-appropriate faces, as

mentioned above. Solutions have also been proposed

involving using password based on users’ own

doodles or their handwriting (Renaud & Ramsay,

2007) and musical motifs (Gibson et al., 2015), which

may be easier for older people to remember.

However, we believe that the work on developing

solutions for older people needs to be better grounded

in more extensive research on the needs and problems

which older people actually encounter, hence the

rationale for the current study.

3 METHOD

An online questionnaire was distributed to a sample

of younger (18 – 30) and older (65 and over) people

in the UK to develop an understanding of their current

habits and challenges with password creation and

management.

3.1 Participants

150 participants were recruited via the Prolific

research participant website (prolific.com), a service

known for the quality of screening its participants and

paying them ethically (Albert & Smilek, 2023;

Douglas et al., 2023) and which allows for the

specification of an age range and other demographic

characteristics. Participants were compensated with

GBP 1.50 (approximately EUR 1.80) for completing

the survey. Inclusion criteria

were for half the sample

(N = 75) to be 65 or older and half to be 18 to 30, all

living in the UK and fluent in English. It was not

thought necessary to ask for a particular level of

technological expertise,

as the participants were all

enrolled in the Prolific online system which required

a password and a moderate level of such expertise to

use.

The demographics of the two groups of

participants are summarised in Table 1. Older

participants were asked if they had any physical or

sensory problems affecting their password use, but

only one participant responded in the affirmative to

this question. However, this may reflect a reluctance

on the part of older people to admit to a disability (the

term disability was deliberately not used in the

question for this reason). Participants were also asked

to rate their level of knowledge of computer and

online security issues (on a 7-point Likert item). Both

groups of participants rated themselves as

significantly above the midpoint of the scale and there

was no significant difference in the ratings of the two

groups (Z = -0.18, n.s.).

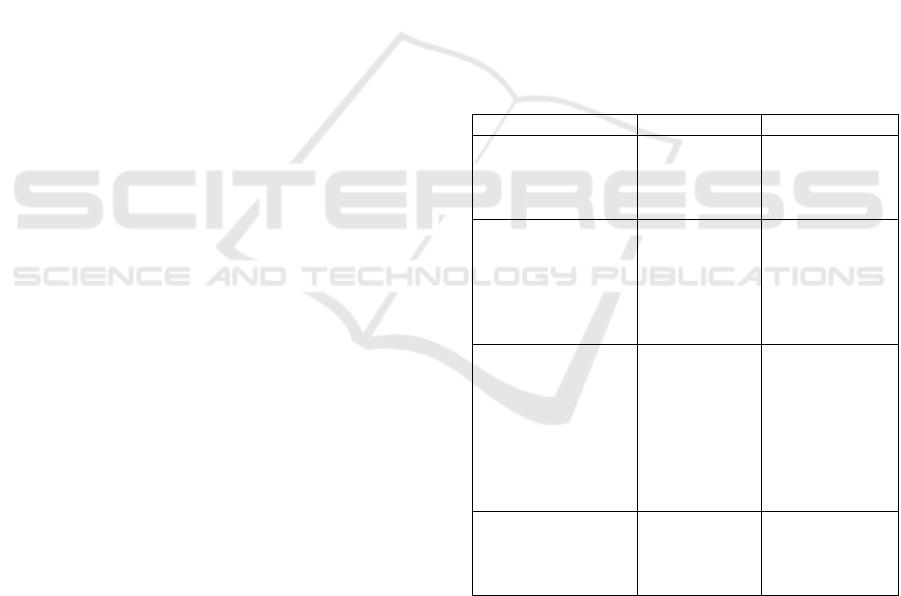

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the participants.

Youn

g

Older

Gender

Women

Men

PNS

36 (48.0%)

37 (49.3)

2

(

2.7

)

42 (56.0%)

33 (44.0)

0

Age

Range

Median

In their 60s

In their 70s

In their 80s

18 – 30

25.0

65 – 89

68.0

52 (69.3%)

19 (25.4%)

4 (5.3%)

Status

Student

Working (f/time)

Working (p/time)

Seeking work

Not working

Retired

PNS

16 (21.3)

44 (58.7)

5 (6.7)

7 (6.7)

1 (1.3)

0

3 (4.0)

0

7 (9.3)

7 (9.3)

0

0

60 (80.0)

1 (1.3)

Online computer/

security knowledge

Median (SIQR)

Z score

(p)

5.0 (0.5)

2.58,

p

= .01

5.0 (0.5)

3.37,

p

< .01

Note. PNS = Prefer not to say

3.2 Online Questionnaire

The online questionnaire comprised 41 questions,

divided into five parts. The first part asked about

general use of passwords, such as what kinds of

accounts the participants have passwords for, and

what devices they access these accounts from. The

second part asked about password creation processes

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

81

and strategies, including what aspects of password

creation participant have problems with, what kinds

of components they use in creating passwords and

what strategies if any they have for creating them.

The third part asked about password management,

including the difficulty of remembering passwords,

whether passwords are written down, shared with

others. The fourth part asked about participants

concerns about the security of their passwords and

password-protected online accounts. The final section

asked the demographic questions (see Appendix for

full text).

Questions consisted of a mixture of 7-point rating

items, usually with a follow-up open-ended question,

and some multiple-choice questions. The rating

questions and multiple-choice questions were

mandatory, but open-ended questions were optional.

The rating items were scored from 1 = least

positive to 7 = most positive, for example on

frequency of encountering problems in creating

passwords from “never” (scored as 1) to “very often”

(scored as 7). Data on the rating items was often

skewed, so non-parametric statistics were used in the

quantitative analysis. As sample sizes were greater

than 30, the Z approximation was used for the

Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test (to test whether ratings

from an individual group differed significantly from

the midpoint of the scale) and the Wilcoxon-Mann-

Whitney Test (to test whether ratings differed

significantly between the two groups) (Siegel &

Castellan, 2000). Differences between the groups in

responses to multiple choice items were analysed

using the chi-square statistic. The open-ended

questions were analysed with simple content

analyses, checked by both authors.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Level of Use of Online Accounts

with Passwords

To understand participants’ level of needing

passwords, they were asked what kinds of online

accounts they needed passwords for (Table 2) and

which devices they used to access these accounts

(Table 3). Both groups of participants use a wide

range of online accounts requiring passwords, with

over 90% of both groups having password protected

accounts for email, banking and online shopping.

There were also some differences between the

groups: perhaps not surprisingly more young

participants having social media accounts, music,

entertainment and games accounts, but fewer having

mass media accounts in comparison to older

participants. In addition to the other account types

listed, older participants included nine further account

types in “other” responses, including gambling (3

participants), wildlife, family history and medical

accounts, while young participants did not mention

any other account types.

Both groups used their mobile/smart phones and

laptops to access their accounts, although more

younger participants used both these devices more

frequently, with slightly more older participants using

tablets.

We decided not to ask participants how many

accounts they have which need passwords or how

many passwords they have, as people now have so

many that answers can be very approximate.

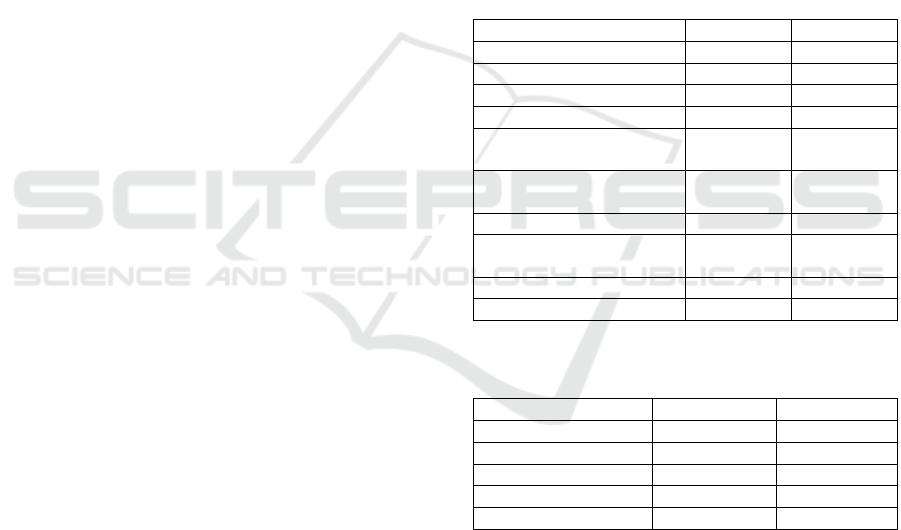

Table 2: Different types of online accounts requiring

passwords used by participants, % (number).

Account t

yp

e Older Youn

g

Email 97.3%

(

73

)

96.0%

(

72

)

Ban

k

94.7

(

71

)

100.0

(

75

)

Shopping 94.7 (71) 90.7 (68)

Social media 78.7 (59) 93.3 (70)

Mass media (e.g.

newspapers)

45.3 (34) 30.7 (23)

Tourism (e.g. hotel

b

ookin

g

, airlines

)

44.0 (33) 52.0 (39)

Music, video streamin

g

40.0

(

30

)

85.3

(

64

)

Entertainment (e.g.

cinema, theatre bookin

g

s

)

33.3 (25) 56.0 (42)

Games 14.7

(

11

)

64.0

(

48

)

Othe

r

13.3

(

10

)

0.0

Table 3: Devices used to access online accounts requiring

passwords by participants % (number).

Device Older Youn

g

Laptop compute

r

64.0% (48) 85.3% (64)

Mobile/smart

p

hone 62.7 (47) 100.0 (75)

Tablet compute

r

46.7 (35) 37.3 (28)

Deskto

p

com

p

ute

r

41.3

(

31

)

45.3

(

34

)

Public terminal 4.0

(

3

)

8.0

(

6

)

4.2 Password Creation

Participants were asked to rate how often they

encountered three possible problems with creating

passwords (“never” =1 to “very often” = 7) (Table 4).

The results were unexpected. Both groups had little

problem in understanding the steps in password

creation processes, both groups’ ratings were

significantly below the midpoint and there was no

significant difference between the ratings of the two

groups (Z = 1.06, n.s.). Both groups had some

difficulties choosing the right character combinations

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

82

for passwords, although older participants had ratings

significantly below the midpoint of the scale, whereas

younger participants had ratings not significantly

different from the midpoint. However, there was no

significant difference between the groups (Z = 1.76,

n.s.). Older participants also had no particular

difficulty with creating passwords of the right length,

with ratings significantly below the midpoint,

whereas young participants did have difficulties with

this, with ratings significantly above the midpoint. In

this case there was a significant difference between

the groups (Z = 2.21, p = 0.027).

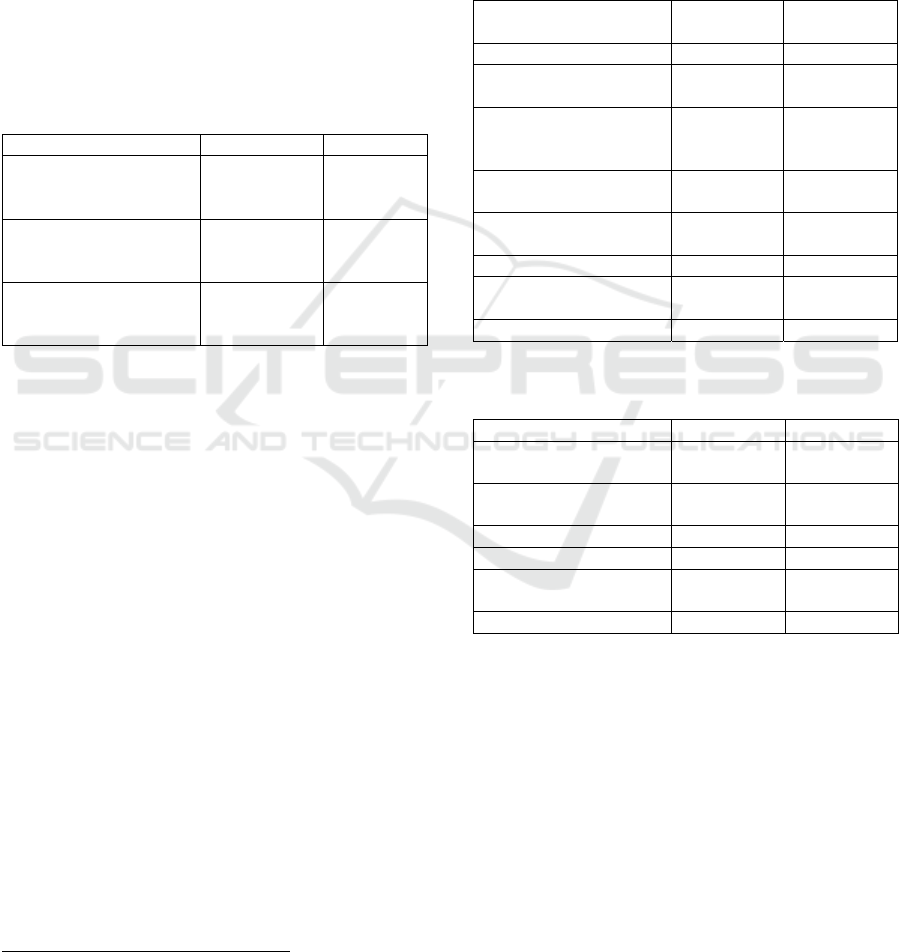

Table 4: Median (semi-interquartile range) of ratings of

password creation problems with Wilcoxon Signed Ranks

Tests on whether the ratings differed significantly from the

midpoint of the scale.

Problem Older Young

Understanding steps in

password creation

p

rocesses

2.0 (1.0)

Z = -7.26

p

< .001

2.0 (1.0)

Z = -6.04

p

< .001

Choosing the right

character combinations

for

p

asswords

3.0 (1.5)

Z = -3.08

p

< .005

4.0 (1.5)

Z = -1.96

n.s.

Creating passwords of

the right length

2.0 (1.5)

Z = -5.53

p

< .001

4.0 (1.5)

Z = -3.29

p

< .001

When participants were asked a follow up open-

ended question about any other problems they

encountered when creating passwords (Table 5),

more than a third (26, 34.7%) of the older participants

responded, more than twice as many as the young

participants (12, 16.0%). There was considerable

overlap in the problems mentioned, with both groups

concerned about creating memorable passwords. But

young participants were most concerned about re-use

of passwords, either exactly the same password or

with small changes (e.g. “Sometimes I cannot reuse

the same password when it needs updating” PY7

1

;

“Making passwords different for different

websites/accounts” PY46) whereas older participants

were most concerned with the use of special, non-

alphanumeric symbols (e.g. “Being told to include a

symbol, but the symbol I choose is not accepted.

VERY annoying!” PO6), which was only mentioned

by one young participant.

Participants were asked what strategies they use

in creating passwords, first from a list of options

(Table 6) and then to describe any other strategies in

a follow-up open-ended question (Table 7).

More than half the participants in each age group

reported re-using passwords with only small changes,

1

Quotes from participants use PY to indicate a young

participant and PO to indicate an older participant.

and nearly half the young participants reported re-

using passwords exactly, significantly more than

older participants (chi-square = 6.46, p = .011). In

addition, significantly more young participants used

familiar dates and numbers (chi-square = 4.51, p =

.034) and familiar names (chi-square = 5.51, p = .019)

in their passwords in comparison to older

participants.

Table 5: Percentage (and number) of participants reporting

other problems in password creation.

Older

N = 26

Young

N = 12

Use of s

p

ecial s

y

mbols 30.8

(

8

)

8.3

(

1

)

Problems creating

memorable passwords

23.1 (6) 25.0 (3)

Different accounts have

different password

requirements

15.4 (4) 8.3 (1)

Creating strong enough

p

asswords

11.5 (3) 0

Overly complex

re

q

uirements

11.5 (3) 0

Password re-use issues 0 41.7 (5)

Lack of requirements in

advance

0 16.7 (2)

Othe

r

26.9

(

7

)

8.3

(

1

)

Table 6: Percentage (and number) of participants using

selected password creation strategies.

Strate

gy

Older Youn

g

Re-using passwords

with small changes

65.3 (49) 63.5 (49)

Familiar dates or

numbers

41.3 (31) 58.7 (44)

Using cryptic sequences 38.7 (29) 37.3 (28)

Familiar names 29.3

(

22

)

48.0

(

36

)

Re-using passwords

exactl

y

26.7 (20) 46.7 (35)

Using common words 20.0 (15) 26.7 (20)

In the follow-up question 68.0% (51) of older

participants but only 32.0% (24) of young

participants provided further strategies (although

some repeated strategies from the list in the previous

question), significantly more older participants than

young ones (chi square = 19.44, p < .001). Strategies

were very varied and providing detailed information

about them could compromise participants

anonymity (although participants did often describe

them in a general way for that reason). Instead, a set

of abstract categories was defined. Strategies which

involved multiple components were defined as

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

83

complex, for example combining an event in the

participant’s past and the location of that event which

part of the date of the event (not an actual strategy

reported but indicative). These would be likely to lead

to strong but memorable passwords. Strategies which

involved only one component were defined as simple,

for example a single word associated with an event in

the participant’s past. In addition, if the strategy

systematically included both characters and numbers,

and sometimes special symbols, it was defined as a

combination strategy. In some instances, this

included substituting numbers in words, for example

“sassy” becomes “$a55y” (this is known as a munged

password

2

). Strategies could be both complex or

simple and combination, depending on whether this

type of strategy was mentioned. Some passwords

were based on the online account, which may make

them insecure. Finally, participants also mentioned

using system or browser generated passwords. The

frequencies of these different strategies are

summarized in Table 7.

Complex strategies were reported by half the older

participants but fewer young participants (although this

difference was not significant, due to small number of

young participants reporting additional strategies, chi

square = 3.15, n.s.). I particular, some of the simple

strategies reported did not appear to be very secure, as

did strategies related to the online account, although

this was an infrequently mentioned strategy. The

numbers of participants using system generated

strategies was also small.

Participants were asked whether they had any

particular concerns about creating passwords in an

open-ended question. Interestingly, on this topic, more

younger participants answered (57.3% of the sample,

43 participants) this question than older participants

(44.0%, 33 participants), although this difference was

not significant (chi square = 2.16, n.s.). Participants

also often raised more than one concern, but again

more instances of concerns were raised by young

participants (53) than older participants (46). Table 8

summarizes the concerns raised. There was some

overlap with the answers given to the question about

problems with creating passwords, but some

interesting different issues emerged.

The top four concerns were the same for both age

groups: remembering passwords, the security of their

passwords and the password systems in general,

making strong passwords and password requirements

being too complex. However, twice the percentage of

young participants were concerned about password

re-use issues (e.g. not making their passwords too

similar with only minor changes) as older

2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munged_password

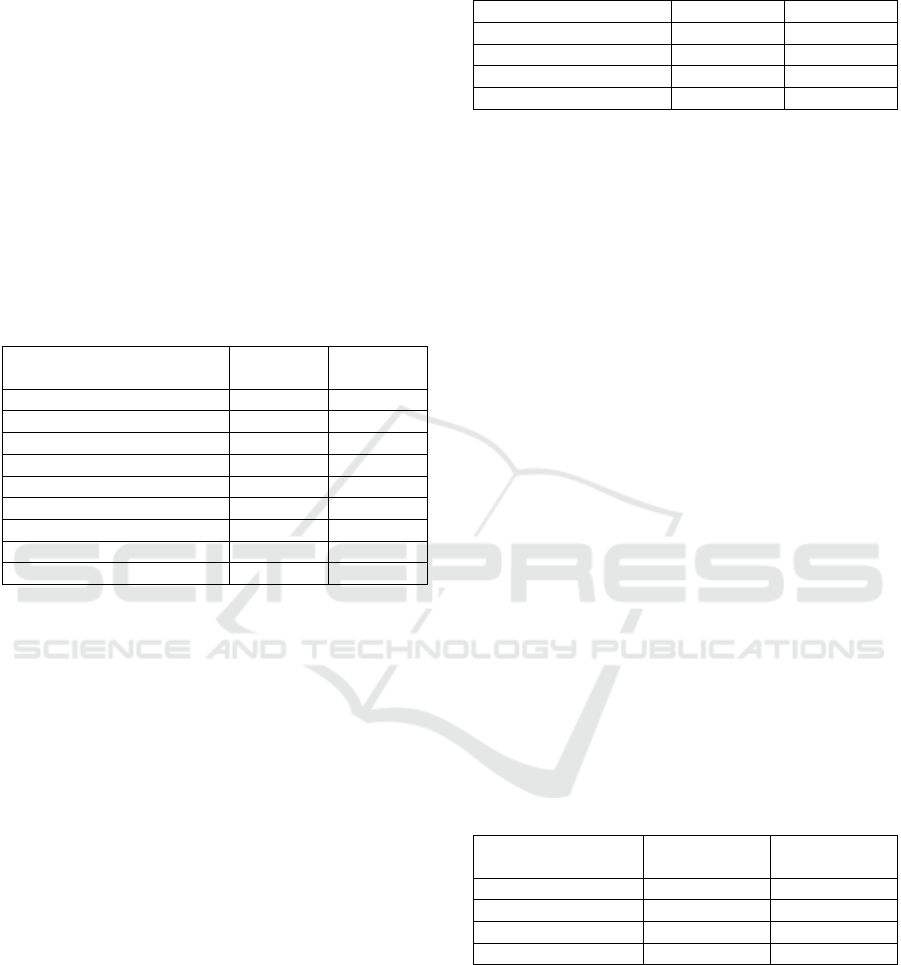

Table 7: Percentage (and number) of participants using

additional password creation strategies.

Older

N = 51

Young

N = 24

Com

p

lex 50.1

(

26

)

29.2

(

7

)

Combination 43.1

(

22

)

37.5

(

9

)

Simple 25.5 (13) 20.8 (5)

System generate

d

15.7 (8) 25.0 (6)

Related to account 7.8 (4) 4.2 (1)

Note. Number total more than 51, as strategies could be

both complex/simple and combination.

Table 8: Percentage (and number) of participants reporting

concerns about password creation.

Older

N = 33

Young

N = 43

Remembering passwords 39.4 (13) 44.2 (19)

Securit

y

24.2 (8) 23.3 (10)

Password strength 21.2 (7) 16.3 (7)

Password requirements too

complex

12.1 (4) 9.3 (4)

Too many passwords require

d

12.1 (4) 4.7 (2)

Password re-use issues 9.1 (3) 8 (18.6)

Being locked out of online

accounts

9.1 (3) 0

Different accounts /different

p

assword re

q

uirements

0 4.7 (2)

Othe

r

6.1 (2) 2.3 (1)

participants, while older participants were more

concerned about being locked out of their online

accounts, often as a consequence of forgetting the

password, or as P22 noted: “I have to write them

down in various places and then remembering where

I have placed them!”.

4.3 Password Management

The equal level of concern by the two age groups

about remembering passwords was also indicated in

the next section of the questionnaire which asked

about password management issues. Participants

were asked to rate how easy or difficult they found it

to remember their passwords (“very easy” = 1 to

“very difficult” = 7), to which both groups responded

with a median of 4.0, slightly, but not significantly

above the midpoint (young: Z = 0.28, n.s.; older: Z =

1.47, n.s.) and with no significant difference between

the groups (Z = -1.74, n.s.). However, when asked in

a follow-up open ended question about their strategies

for remembering passwords, older participants were

significantly more likely to report having strategies

than young participants (young: 31, 41.3%; older:

60.0%; chi-square = 5.23, p = .02).

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

84

In fact, the range and frequency of different

strategies did not greatly between groups. The most

common strategy for remembering passwords for both

age groups was to write them down, but participants in

both groups had additional strategies for protecting the

information such as encrypting a computer file. About

20% of each group re-used passwords with small

changes, but again there were often additional strate-

gies in their implementation, for example “

the pass-

words are similar with different endings e.g .numbers

or characters - so the main part of the password is often

the same” (PO35). A small number of participants did

not write down the actual password, but a hint which

would prompt them to remember the password.

Table 9: Percentage (and number) of participants reporting

particular strategies for remembering passwords.

Older

N = 45

Young

N = 31

Writin

g

down 40.0

(

18

)

32.3

(

10

)

Re-use/small chan

g

es 17.8

(

8

)

22.6

(

7

)

Memorable events/dates 15.6

(

7

)

12.9

(

4

)

Account relate

d

8.9 (4) 12.9 (4)

Password manager/browse

r

8.9 (4) 9.7 (3)

Hint note

d

4.4

(

3

)

9.7

(

3

)

Re-use/same 4.4

(

3

)

6.5

(

2

)

Mnemonic 4.4

(

3

)

0

Other/unclea

r

0 22.6 (7)

About 10% of each age group used a strategy

based on creating passwords which related to the

account, as mentioned above, which does not seem

very secure. Another 10% used password managers,

either stand-alone products or the browser or

operating system facility to store passwords. Two of

the older participants used mnemonics to create and

then remember passwords, for example the password

EGBDF might be remembered from the phrase

“every good boy deserves favour” (which is actually

a mnemonic for remembering the notes on the treble

clef). It is interesting that none of the young

participants mentioned mnemonics.

Participants were also asked whether they ever

share their passwords (from “never” = 1 to “always”

= 7). Both groups reported never or rarely sharing

passwords with medians of 1.0, significantly below

the midpoint (young: Z = -7.47, p < .001.; older: Z =

-7.66, p < .001). However, due to the distribution of

ratings, there was a significant difference between the

groups (Z = 2.46, p = 0.01), with young participants

more likely to share their passwords. 73.3% of older

participants said they never share their passwords,

compared to 54.7% of older participants. Young

participants were also willing to share with a wider

range of people (Table 10).

Table 10: Percentage (and number) of participants sharing

passwords with particular groups of people.

Older Young

Spouse/partne

r

20.0 (15) 24.0 (18)

Other family members 17.3 (13) 28.0 (21)

Friends 0 12.0

(

9

)

Collea

g

ues 0 5.3

(

4

)

4.4 Concerns About Password and

Online Account Security

Finally, participants were asked how worried they are

about their passwords being stolen or compromised in

some way (“not at all” = 1 to “a great deal” = 7). Both

groups gave median ratings of 4.0, not significantly

different from the midpoint of the scale (young: Z = -

0.76, n.s.; older: Z = -1.52, n.s.), indicating that they

have moderate levels of worry. Unfortunately, we

failed to include a general follow-up question about

what their worries were (a missed opportunity).

However, we did ask whether they had had any bad

experiences with their password protected online

accounts. 17.3% (13) of older participants and 24.0%

(18) young participants reported they had, not a

significant difference between the groups (chi-square

= 1.02, n.s.). Although the numbers are small, there

were interesting differences in a follow-up question

in which participants were invited to describe any

recent bad experiences. All participants who reported

having had bad experiences provided an example

(Table 11). Older participants were much more likely

to have been locked out of an online account, whereas

young participants were more likely to have been

hacked or been involved in a data breach (Gmail and

Instagram data breaches were mentioned).

Table 11: Percentage (and number) of participants who had

had a bad experience with a password protected account.

Older

N = 13

Young

N = 18

Locked out 53.8

(

7

)

22.2

(

4

)

Hacke

d

30.8

(

7

)

61.1

(

11

)

Phishe

d

15.4 (2) 5.6 (1)

Data breach 0 16.7 (3)

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the behaviours, problems, and

strategies and behaviours used with passwords for

online accounts of a sample of older people in the UK

and compared them with a similar sample of young

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

85

people. The results were surprising, showing that

there were differences between the two age groups,

but not necessarily the ones which would have been

expected, nor those predicted from a reading of the

research literature on the physical and cognitive

effects of aging.

However, before discussing the findings and their

implications, it is important to note the major

limitation of this study, the nature of the sample of

older participants. Firstly, the majority of the older

participants would be classified as “young old”, as

nearly 70% were in their late 60s (see Table 1). Only

25% of the older participants were in their 70s and

5% in their 80s. Thus, most participants are probably

not yet experiencing the major effects of aging.

However, this age group is a substantial segment of

the older population, and are the most active online,

so may need more support with passwords and

authentication than they are currently receiving. It is

also important to realise that people who are currently

part of the young old age group or soon entering it

likely have very different attitudes to and experience

of digital technologies and the online world compared

to people in the “old” (75 – 84 years) and “oldest old”

(85 and over) groups, given the major changes in

technology we have seen in the last 40 years (Petrie,

2023). But the results of this study do not address the

needs of these groups of population adequately.

Further research is needed about the password and

authentication experiences and needs of those age

groups.

Secondly, participants in both age groups were

recruited from Prolific, an online research participant

recruitment platform. That means that participants

will be familiar, and probably quite confident, in

using online accounts. This will probably affect the

sample of older participants most, meaning they are

not necessarily representative of the older population

of the UK in general. However, it is interesting that

the information they provided about their use of

devices is in agreement with current statistics for the

older population (see Table 3). The most frequently

mentioned device for accessing online accounts

mentioned by the older participants was a laptop

computer, closely followed by a mobile phone, with

other devices mentioned by less than have the

participants. These figures align well with data from

AgeUK (2024) about the devices that people 65 and

over in the UK use to access the internet (albeit a

slightly different question from those devices which

report 75% of older people using a mobile phone,

61% a laptop or desktop computer and 49% a tablet

computer.

In addition, both age groups were recruited

through Prolific and rated their online

computer/security knowledge very similarly. So one

can argue that the groups are similar to each other and

therefore the differences are valid, even if not

representative of the whole population. Certainly,

differences between the groups are unlikely to be due

to differences in familiarity with the online world or

knowledge of online security issues. One could even

argue that if this group of older participants are

having difficulties with certain aspects of password

creation and management, the wider population are

likely to have more severe problems. The open

question is would they be the same problems.

Turning to the results of the study, the key

findings on password creation were that both groups

rated the difficulty of understanding the password

creation process as low, but had moderate difficulty

with choosing the right combination of characters,

numbers, and special symbols for a password. Later

questions showed older people had particular

problems with difficulty making strong passwords

which was rarely mentioned by young participants.

The first surprising result was that on password

length, older participants reported having little

difficulty with this aspect of password creation, while

young participants had considerable difficulty.

However, on a follow-up opened ended question,

many more older people elaborated on their

difficulties, which included the use of special

symbols and difficult making strong passwords. On

the other hand, young participants most often

expressed difficulty in re-using previous passwords.

It is hard to find information in previous studies with

older people with which to compare these findings,

but they are generally in line with results from Carter

(2015) and Ray et al. (2021) that older people were

using familiar words and phrases for passwords, thus

perhaps avoiding the complexity of combinations of

characters, numbers and symbols.

However, in relation to strategies for creating

passwords, older participants provided many more

explanations and more complex strategies. These

strategies often included very smart ways of

combining at least letters or words and numbers,

although special symbols were mentioned very

infrequently (the specific strategies are not discussed

in detail to protect participants’ anonymity).

Worryingly, nearly half the young participants who

replied reported re-using passwords exactly across

online accounts, far more than young participants.

The main concerns about password creation were

the same for both groups: remembering passwords,

password and system security, password strength and

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

86

password requirements being too complex. Indeed,

when specifically asked about difficulty of

remembering passwords, both groups gave moderate

ratings of difficulty. These two results indicate that

the older participants were not experiencing any more

difficulty than young participants with remembering

their passwords, which is not what would be predicted

from the literature. The reason for this might lie in the

greater number and complexity of the strategies

reported by the older participants for creating

passwords which they also reiterated as memory

strategies.

In addition to those four main concerns, it is

noteworthy that some older participants were

concerned about being locked out of their accounts,

often as a result of forgetting their password (but also

because of complexities of the authentication

process), a concern never raised by young

participants. Whereas young participants tended to be

concerned with password re-use issues, such as the

poor security of re-using old passwords (which they

did as they could not remember so many). It is also

interesting that the range and frequency of strategies

for remembering passwords, such as writing them

down in a (hopefully) secure location, did not differ

markedly between young and older participants. We

could not identify any previous studies with older

participants which discussed what strategies they use

to create and remember passwords, so we believe this

is new information.

All these results showing that there are more

similarities than differences between young and older

people on memory issues in relation to passwords.

These findings agree with the early work by Pilar et

al. (2012) which found that age was not a significant

predictor of forgetting or confusing passwords. None

of the subsequent studies which actually involved

older and young participants identified remembering

passwords as a problem, and Petrie et al (2022) found

that neither UK nor Chinese older participants

highlighted this as a problem. Yet numerous

researchers cite this as a major problem for older

password users that needs addressing.

Indeed, the current results suggest that systems

specifically designed to support older people in

remembering their passwords are somewhat

misguided. All participants, regardless of age, have

concerns about remembering the wide variety of

passwords that are now needed to manage online

accounts. Therefore, everyone needs more support in

this area. Providing systems specifically for older

people risks placing them in a “digital ghetto”,

making them feel inferior in

capacity as users in

comparison to young people, when this is not the

case. What is needed is further research to establish

whether young and older password users need

different types of support to help them in the memory

task. But this could be offered as a range of options

for all users, rather than a special aid for all users,

following universal design (Ostroff, 2011) principles.

For example, Al-Ameen et al. (2015) proposed cued-

recognition authentication systems that provides

users with multiple cues in different modalities

(visual, verbal, and spatial) and lets them choose the

cues that best fit their preferences and needs. Such a

system would accommodate many different people,

with different cognitive styles, different disabilities,

including older people, without making them feel

peculiar. It is also the kind of system that’s more

likely to be implemented and maintained by

developers, as only one system is needed for all users,

rather than needing particular additions or variations

to accommodate the needs of particular groups, as is

currently the case with audio CAPTCHAs for visually

disabled users.

A final argument which needs addressing is

whether passwords will soon become

obsolete and

replaced by more effective and secure authentication

methods such as biometrics. Commentators having

been discussing the “death” of passwords for at least

20 years (e.g. Potter, 2005), and yet currently we

seem to have more and more passwords to deal with.

Biometrics are certainly becoming more common

with some personal devices using fingerprint and face

recognition for authentication, but these methods are

not without their problems for disabled and older

users (e.g. Petrie & Wakefield, 2020). We believe

passwords are going to be around for some

considerable time yet, so the issues of creating and

using them need to be addressed.

In conclusion, this study has thrown some new

light on the needs and problems of older people in

relation to password creation and use. The results

were surprising and interesting and may lead to some

rethinking of how best to support older people in their

use of password-protected online accounts.

REFERENCES

AgeUK. (2024). Briefing: facts and figures about digital

inclusion and older people. Available at:

https://www.ageuk.org.uk/siteassets/documents/report

s-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/active-comm

unities/internet-use-statistics-june-2024.pdf

Ahmed, E., DeLuca, B., Hirowski, E., Magee, C., Tang, I.,

& Coppola, J.F. (2017). Biometrics: Password

replacement for elderly? 2017 IEEE Long Island

Systems, Applications and Technology Conference

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

87

(LISAT), Farmingdale, NY, USA, 2017, pp. 1-6, doi:

10.1109/LISAT.2017.8001958.

Al-Ameen, M.N., Wright, M., & Scielzo, S. (2015).

Towards making random passwords memorable:

Leveraging users' cognitive ability through multiple

cues. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘15).

ACM Press.

Albert, D.A., & Smilek, D. (2023). Comparing attentional

disengagement between Prolific and MTurk samples.

Scientific Reports, Art. 20574.

Alnfiai, M. (2020). A novel design of audio CAPTCHA for

visually impaired users. International Journal of

Communication Networks and Information Security,

12(2), 168 – 179.

Andrew, S., Watson, S., Oh, T., & Tigwell, G. W. (2020).

A review of literature on accessibility and

authentication techniques. Proceedings of the 22nd

International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on

Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS 22). ACM

Press.

Brown, A.S., Bracken, E., Zoccoli, S., & Douglas, K.

(2004) Generating and remembering passwords.

Applied Cognitive Psychology 18: 641–651.

Carter, N. C. (2015). Graphical passwords for older

computer users. Adjunct Proceedings of the 28th

Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software

& Technology (UIST '15 Adjunct). ACM Press.

Carter, N.C., Li, C., Li, Q., Stevens, J.A., Novak, E., Qin,

Z., & Yu, J. (2017). Graphical passwords for older

computer users. Proceedings of HotWeb ’17. ACM.

Douglas, B.D., Ewell, P.J. & Brauer, M. (2023). Data

quality in online human-subjects research: comparisons

between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics

and SONA. PLoS ONE 18(3): e0279720.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279720

Fanelle, V., Karimi, S., Shah, A., Subramanian, B., & Das,

S. (2020). Blind and human: exploring more usable

audio CAPTCHA designs. In Sixteenth Symposium on

Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2020). USENIX

Association.

Fuglerud, K. & Dale, O. (2011). Secure and inclusive

authentication with a talking mobile one-time-password

client. IEEE Security & Privacy, 9(2), 27-34.

Furnell, S., Helkala, K., & Woods, N. (2021).

Disadvantaged by disability: Examining the

accessibility of cyber Sscurity. In M. Antona & C.

Stephanidis (Eds.), Universal Access in Human-

Computer Interaction. Design Methods and User

Experience (Proceedings of HCII 2021). Springer.

Gibson, M., Renaud, K., Conrad, M. & Maple, C. (2015).

Play that funky password!: Recent advances in

authentication with music. In M. Gupta (Ed.),

Handbook of Research on Emerging Developments in

Data Privacy. IGI Global.

Holman, J., Lazar, J., & Feng, J. (2008). Investigating the

security-related challenges of blind users on the web. In

Langdon, P., Clarkson, J., Robinson, P. (Eds.),

Designing Inclusive Futures. Springer.

Holman, J., Lazar, J., Feng, J.H., & D’Arcy, J. (2007).

Developing usable CAPTCHAs for blind users.

Proceedings of the 9th International ACM

SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and

Accessibility (ASSETS ’07). ACM Press.

Jittibumrungrak, P., & Hongwarittorrn, N. (2019). A

Preliminary Study to Evaluate Graphical Passwords for

Older Adults Proceedings of the 5th International ACM

In-Cooperation HCI and UX Conference. ACM Press.

Juozapavičius, A., Brilingaitė, A., Bukauskas, L., & Lugo,

R.G. (2022). Age and gender impact on password

hygiene. Applied Sciences, 12, 894.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ app12020894

Lazar, J., Feng, J., Brooks, T., Melamed, G., Wentz, B.,

Holman, J., Olalere, A. & Ekedebe, N. (2012). The

SoundsRight CAPTCHA: an improved approach to

audio human interaction proofs for blind users. In

Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’12). ACM Press.

Mentis, H. M., Madjaroff, G., & Massey, A.K. (2019).

Upside and downside risk in online security for older

adults with mild cognitive impairment. Proceedings of

the 2019 SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (CHI ‘19). ACM Press.

Morrison, B., Coventry, L., & Briggs, P. (2021). How do

older adults feel about engaging with cyber-security.

Human Behaviour and Emerging Technologies,

https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.291

Nicholson, J., Coventry, L., & Briggs, P. (2013a). Age-

related performance issues for PIN and face-based

authentication systems. Proceedings of the 2013

SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems (CHI ‘13). ACM Press.

Nicholson, J., Coventry, L., & Briggs, P. (2013b). Faces

and pictures: understanding age differences in two

types of graphical authentications. International Journal

of Human-Computer Studies, 71(10), 958-966.

Nielsen, L. (2024). Personas, scenarios, journey maps, and

storyboards. In C. Stephanidis & G. Salvendy (Eds.),

User experience methods and tools in human-computer

interaction. CRC Press.

Ostroff, E. (2011). Universal Design: An Evolving

Paradigm. In W.F.E. Preiser & K.H. Smith (Eds.),

Universal Design Handbook (2

nd

edition). McGraw-

Hill.

Pearman, S., Zhang, S.A., Bauer, L., Christin, N., & Cranor,

L.F. (2019). Why people (don’t) use password

managers effectively. In Fifteenth Symposium on

Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2019). USENIX

Association.

Petrie, H. (2023). Talking ‘bout my generation … or not?

The digital technology life experiences of older people.

Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ’23),

Art. 420, 1 – 9. New York: ACM Press.

Petrie, H., Merdenyan, B., & Xie, C. (2022). Password

Challenges for Older People in China and the United

Kingdom. In Miesenberger, K., Kouroupetroglou, G.,

Mavrou, K., Manduchi, R., Covarrubias Rodriguez, M.,

& Penáz, P. (Eds.), Computers Helping People with

Special Needs. ICCHP-AAATE 2022. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, vol 13342. Springer.

Petrie, H. & Schmeelk, S. (2024). Towards

recommendations for the universal design of online

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

88

authentication systems. In Proceedings of Universal

Design 2024. Oslo, Norway.

Petrie, H. & Wakefield, M. (2020). Remote moderated and

unmoderated evaluation by users with visual

disabilities of an online registration and authentication

system for health services. Proceedings of the 9th

International Conference on Software Development

and Technologies for Enhancing Accessibility and

Fighting Info-exclusion (DSAI 2020). New York:

ACM Press.

Pilar, D.R., Jaeger, A., Gomes, C.F.A. & Stein, L.M.

(2012). Passwords usage and human memory

limitations: a survey across age and educational

background. PLoS ONE, 7(12). e51067.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051067

Potter, B. (2005). Are passwords dead? Network Security,

9, 7 - 8.

Ray, H., Wolf, F., Kuber, R., & Aviv, A.J. (2021). Why

older adults (don’t) use password managers. In

Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium.

USENIX.

Renaud, K. & Ramsay, J. (2007). Now what was that

password again? a more flexible way of identifying and

authenticating our seniors. Behaviour and Information

Technology 26(4), 09-322.

Renaud, K., Scott-Brown, K.C., & Szymkowiak, A. (2018).

Designing authentication with seniors in mind. In

Proceedings of the Mobile Privacy and Security for an

Ageing Population workshop at the 20th International

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with

Mobile Devices and Services (MobileHCI 2018).

ACM.

Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) (2024).

Key information and statistics on sight loss in the UK.

https://www.rnib.org.uk/professionals/health-social-

care-education-professionals/knowledge-and-research-

hub/key-information-and-statistics-on-sight-loss-in-

the-uk/

Sauer, G. Holman, J., Lazar, J., Hochheiser, H. & Feng, J.

(2010). Accessible privacy and security: a universally

usable human-interaction proof tool. Universal Access

in the Information Society, 9, 239 – 248.

Siegel, S. & Castellan, N.J. Jr. (2000). Nonparametric

statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

Vu, KP.L. & Hills, M.M. (2013). The influence of password

restrictions and mnemonics on the memory for

passwords of older adults. In Yamamoto, S. (Ed.),

Human Interface and the Management of Information:

Information and Interaction Design. Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, vol 8016. Springer.

Whitty, M., Doodson, J., Creese, S., & Hodges, D. (2015).

Individual differences in cyber security behaviors: an

examination of who is sharing passwords.

Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking,

18(1). DOI: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0179

Yuan, L., Chen, Y, Tang, J., & Cranor, L.F. (2024).

Account password sharing in ordinary situations and

emergencies: a comparison between young and older

adults. In Proceedings on Usable Privacy and Security

(SOUPS). USENIX.

APPENDIX: QUESTIONNAIRE

Q0. Please enter your Prolific ID:

Q1. Which types of online accounts do you have

passwords for? (please select as many that apply to

you):

• Online bank accounts

• Online shopping sites

• Social media accounts (e.g. Facebook, WeChat,

Instagram, Twitter)

• Online newspapers, magazines, mass media (e.g.

BBC, CNN)

• Entertainment booking sites (e.g. theatres,

cinemas etc.)

• Game sites (e.g. Steam)

• Music and video streaming sites (e.g. YouTube,

Spotify)

• Tourism sites (e.g. hotel, airline booking sites,

TripAdvisor)

• Email accounts

• Work related accounts

• Other types of accounts, please describe briefly

Q2. From which devices do you log into these

accounts? (please select as many that apply to you):

• Mobile phone

• Tablet device (e.g. iPad)

• Laptop computer

• Desktop computer

• Public terminals (e.g. shared computers at

libraries)

• Other, please describe briefly

Q4. How often or not do you encounter these

problems when creating passwords?

(presented as a grid with options from Never to Very

often on 7-point items)

• Problems with choosing the right character

combinations (e.g. letters, numbers, special

characters)

• Understanding the steps in the password creation

process

• Problems with making the password of the

required length

Q5. Are there any other problems you would like to

mention that you have encountered when creating

passwords? If so, please describe briefly. (open-

ended)

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

89

Q6. In creating new passwords, do you use any of the

following? (Please select as many that apply to you)

• Use familiar names (e.g. family members,

famous people)

• Use familiar dates or numbers (e.g. birthdays)

• Use common words

• Use cryptic sequences (e.g. nonsense words,

random sequences of letters)

• Re-use older passwords exactly

• Re-use older passwords with small changes

• None of these

Q7. Please briefly describe any other strategies you

use to create passwords (open-ended)

Q8. Do you have any particular concerns about the

process of creating passwords? (open-ended)

Q9. How easy or difficult is it for you to remember

your passwords?

(presented as a 7-point rating item with options from

“Very easy” to “Very difficult”)

Q10. Do you have any particular strategies for

remembering your passwords?

(Yes/No)

If Yes to Q10:

Q11. What strategies do you use to remember

passwords? Please describe briefly (open-ended)

Q12. How often do you write down your passwords?

(presented as a 7-point rating item with options from

“Never to “Always”, skip to Q14 is answer is

“Never”)

Q13. Where do you write your passwords down?

(multiple-choice)

• On paper, kept somewhere at home

• On paper, in my wallet or purse

• In a computer file

• Other (please explain briefly)

Q14. How often do you share your passwords with

others?

(presented as a 7-point rating item with options from

“Never to “Always”, skip to Q16 if answer is

“Never”)

Q15. Who do you share your passwords with? (select

all that apply to you)

• Family members

• Spouse/partner

• Friends

• Colleagues

• Others (Please specify)

Q19. Do you have any particular concerns or fears

about remembering and using your passwords? If so,

please describe briefly. (open-ended)

Q20. How much do you worry about your passwords

being stolen, guessed or compromised in some way?

(presented as a 7-point rating item with options from

“Not at all” to “A great deal”)

Q21. Have you had any bad experiences with

passwords on your online accounts?

(Yes/No, Skip to D1 if answer is No).

Q22. Please describe any recent bad experiences you

have had with passwords on your online accounts

(open-ended)

D1. What gender do you identify as?

• Male

• Female

•

Non-binary / third gender

• Prefer not to say

• Prefer to self-identify (Please explain if you

wish)

D2. How old are you (to nearest year)?

D3. What is your nationality?

• British

• Other (Please specify)

D2 and D3 were included as although Prolific should

only invite participants who meet the requested

criteria, this sometimes seems to fail.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

90

D4. Are you ...

• A Student

• Working Full-Time (including self-employed)

• Working Part-Time (including self-employed)

• Looking for work

• Retired

• Prefer not to say

• Other

If Working to D4:

D5. What is your occupation? (open-ended)

If Retired to D4:

D6. What was your occupation when you worked?

(open-ended)

If Student to D4

D7. What are you studying for?

• A-levels or equivalents

• Bachelor's degree

• Higher degree (e.g. Master's, PhD)

• Professional qualification, please explain

• Other, please explain

• Not studying for a qualification at the moment

If Student to D4

D8. What is your main area of study? (open-ended)

D9. How knowledgeable or not do you feel about

computer/online security issues?

(presented as a 7-point rating item with options from

“Not at all knowledgeable to “Very Knowledgeable”)

D10. Do you work or have you ever worked in a job

related to computer/online security?

(Yes/No)

If Yes to D10

D11. Could you briefly describe your work in

computer/online security and when you worked in

this area?

Password Authentication for Older People: Problems, Behaviours and Strategies

91