STELLA

+

: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep

Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

Franz Plocksties

1 a

, Christoph Niemann

1

, Mareike Fauser

2

, Alexander Storch

2

,

Dirk Timmermann

1

and Christian Haubelt

1

1

Institute of Applied Microelectronics and Computer Engineering, University of Rostock, Germany

2

Department of Neurology, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany

Keywords:

Deep Brain Stimulation, Long-Term, Preclinical DBS Device, Adaptive DBS.

Abstract:

Rodent models are essential for our understanding of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) mechanisms. How-

ever, most existing preclinical devices lack to support the broad experimental range required for modern DBS

approaches. This paper presents the neurostimulation system STELLA

+

, which aims to enhance the scope

of long-term DBS research in rodent models. STELLA

+

upgrades the previous STELLA system that has

been successfully used in several rodent studies. It features technical and architectural enhancements to in-

crease performance and functionality for long-term DBS experiments. Initial in vitro findings demonstrate that

STELLA

+

delivers charge-balanced, current-controlled pulses with high accuracy across a range of stimula-

tion settings up to a compliance voltage of 4.3 V. With a maximum current consumption of 25.1 µA at 4.3 V

in bilateral DBS-on mode, STELLA

+

enables long-term experiments of 6.8 weeks using a 29 mAh lithium-

ion battery. Additionally, STELLA

+

includes a Bluetooth Low Energy module and the capability to acquire

and compute on-board physiological data, enabling adaptive DBS applications. All these features are housed

within a compact size of 21x14.5x4 mm, minimizing the impact on rodents. Compared to the other state-

of-the-art DBS devices, STELLA

+

demonstrates enhanced efficiency in stimulus generation and a uniquely

comprehensive feature set.

1 INTRODUCTION

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) has emerged as a re-

markable therapeutic approach for the management

of various neurological and psychiatric disorders. By

delivering electrical pulses to specific brain regions

through implanted electrodes, DBS has shown sig-

nificant results in symptom control and improving

patients’ quality of life. While the therapy is well-

established for the treatment of movement disorders,

such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and tremor, its

potential for other diseases is also being explored

(Harmsen et al., 2020). However, the precise mech-

anisms by which DBS develops its therapeutic ef-

fects are still under active investigation (Hamani and

N

´

obrega, 2010; Jakobs et al., 2019). To address the

open questions, preclinical in vivo experiments are es-

sential. Rodent models have been widely employed in

DBS research, allowing for investigations into elec-

trophysiological, neurochemical and behavioral as-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0433-7703

pects (Ruiz et al., 2022). However, the progress of

past studies has been impeded by runtime-restricted

and bulky stimulation devices mounted on the ro-

dent’s head (K

¨

olbl et al., 2016; Fluri et al., 2017;

Pinnell et al., 2015; Pinnell et al., 2018; Forni et al.,

2012; Liu et al., 2017; Ewing et al., 2013) or back

(Kouzani et al., 2017; Badstuebner et al., 2017; Heo

et al., 2015). These setups not only led to a signif-

icant strain on the animals, but also resulted in fre-

quent device failures, e.g. due to cable breaks and

mounting issues caused by the animals’ movement.

To overcome these limitations, the fully implantable

stimulation device called STELLA (software defined

implantable modular platform) was introduced, en-

abling reliable and long-term stimulation in rodents

(Plocksties et al., 2021a). Furthermore, this device

is highly suitable for sensitive behavioral studies in

DBS research as it supports the refinement aspect

of the 3R principles through the reduction of strain

for the animals (D

´

ıez-Solinska et al., 2022). How-

ever, despite promising results from rodent studies

conducted with STELLA (Plocksties et al., 2021a;

74

Plocksties, F., Niemann, C., Fauser, M., Storch, A., Timmermann, D. and Haubelt, C.

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents.

DOI: 10.5220/0013305200003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 74-87

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

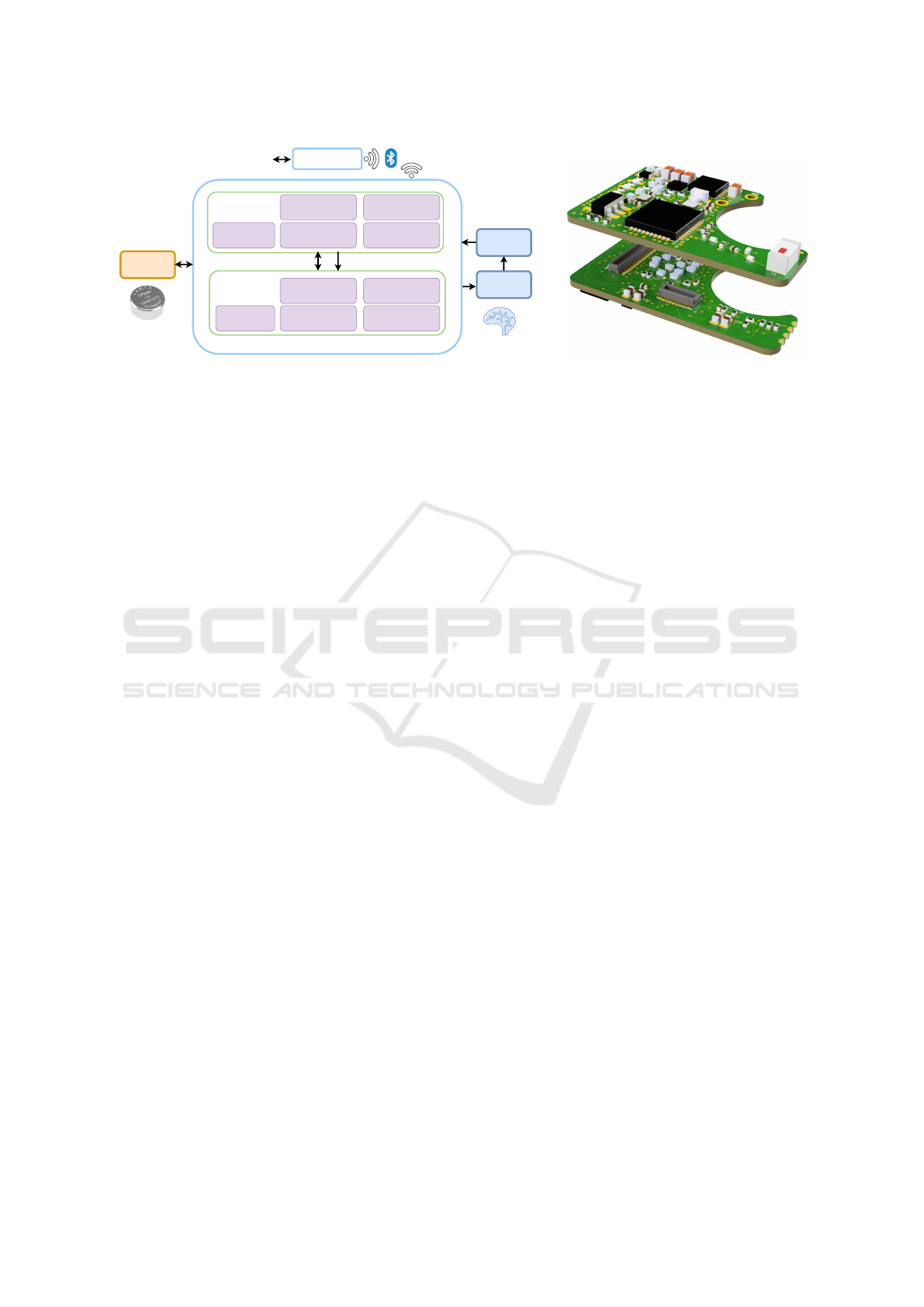

Implant Comm.

(LEDs, BLE, Magn.)

Battery &

Power Management

Temperature Sensor

Level Conversion

Upper PCB

Lower PCB

Li-ion

Battery

Deep Brain

Stimulation

SIG

PWR

I/V Generation of

DBS Pulses

3D Accelerometer

Rechargeable over

electrode leads

Impedance

Characterization

Built-in Self-test

Extracorporeal

Device

Feedback

nRF52 µ-Controller

(Processing + BLE)

MSP430 µ-Controller

(DBS Management)

Laboratory

Infrastructure

(a) (b)

Figure 1: (a) STELLA

+

system overview. (b) 3D design of the upper and lower PCB.

Plocksties et al., 2022; Koschay et al., 2022; Statz

et al., 2023a; Statz et al., 2023b), a crucial gap re-

mains. Like most other state-of-the-art preclinical

DBS devices, STELLA has limitations in support-

ing a wide range of experimental applications, includ-

ing research on adaptive DBS (aDBS). In clinical ap-

plication, aDBS aims to optimize and individualize

therapeutic outcomes by dynamically adjusting the

stimulation parameters based on feedback data (Neu-

mann et al., 2023). As research into suitable biomark-

ers and control methods is still ongoing, the transla-

tion of aDBS between clinical and laboratory settings

is essential. To address this gap, a novel DBS de-

vice named STELLA

+

has been designed that builds

on the strengths of its predecessor while providing

innovative features, which significantly increase ex-

perimental versatility. Key improvements include a

more functional stimulation unit, multiple sensors,

on-board signal processing capabilities and wireless

connectivity, enabling researchers to explore diverse

stimulation strategies in rodents.

This paper demonstrates the start-up phase of

STELLA

+

, focusing on the technical implementa-

tion and performance analysis of the stimulation unit.

Section 2 describes the technical specifications of

STELLA

+

in detail. Section 3 presents performance

metrics of STELLA

+

from in vitro experiments and a

comprehensive overview of its feature set compared

to state-of-the-art devices in this field. Finally, sec-

tion 4 summarizes the findings.

2 TECHNICAL REALIZATION

2.1 System Overview

STELLA

+

utilizes a two-stacked PCB design in or-

der to double available component area compared to

a standard single PCB configuration (see Fig. 1 (b)).

The PCBs are stacked together using miniaturized

connectors (Molex 505417-3410) allowing for the

transfer of power and signals between the two boards.

Fig. 1 (a) illustrates the system overview, highlighting

the functional distribution between the PCBs.

The upper PCB is responsible for battery and

power management, while also housing a Bluetooth

Low Energy (BLE) module for wireless communica-

tion. It also includes a magnetic sensor for triggering

basic device tasks and LEDs (red, green, IR) for sta-

tus indication. Additionally, it incorporates sensory

units, including a temperature sensor for monitoring

the animal’s temperature and a circuit for character-

izing the impedance of the electrode and tissue com-

ponent over a broad spectrum (details not provided in

this paper). On the other hand, the lower PCB focuses

on the generation of charge-balanced DBS pulses for

two channels, including an appropriate level transla-

tion to ensure compatibility between two voltage do-

mains (see Section 2.2.3, 2.3.4). It also incorporates a

built-in self-test to verify whether the electrical stim-

ulation is within a valid range. Finally, it integrates a

3-axis accelerometer sensor for motion sensing of the

animal.

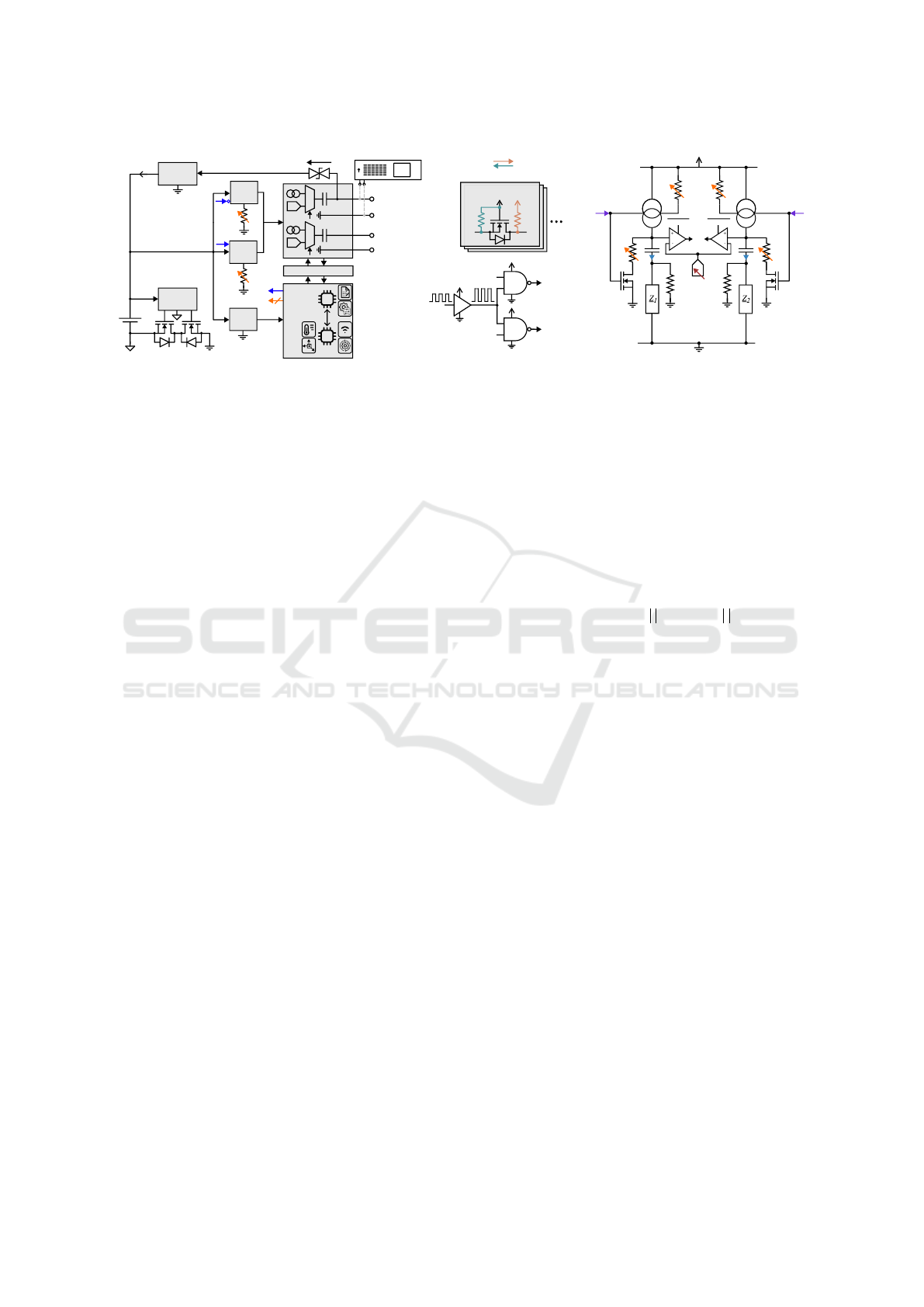

2.2 Power Management

The power management of STELLA

+

is conceptually

presented in Fig. 2(a).

2.2.1 Low-Power Approach

STELLA

+

has been designed to be highly modular,

allowing unused modules to be selectively powered

down to the nA range via dedicated EN signals or the

system bus. This approach permits the platform to

be used in an energy-efficient fashion for each spe-

cific application. Furthermore, the platform utilizes

two microcontrollers to effectively manage various

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

75

tasks. The nRF52833, which is built around a 32-

bit ARM Cortex-M4, is used for computationally in-

tensive tasks such as adaptive DBS algorithms. Ad-

ditionally, the nRF52833 includes an RF transceiver

module supporting Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) for

wireless communication with the outside world. In

contrast, the MSP430FR2355 microcontroller, which

features an ultra-low power architecture, is responsi-

ble for controlling and monitoring the stimulation sig-

nals.

2.2.2 Battery

The platform is powered by the rechargeable Li-

ion button cell CP9440 A4X from VARTA (VARTA,

2019) providing a capacity of 29 mAh. With its com-

pact dimensions of Ø9.4x4 mm, and low weight of

0.9 g, this battery is highly suitable for applications

with critical space.

2.2.3 Voltage Regulation

The previous STELLA implements a unified ap-

proach, where the control and stimulation unit share

the same supply voltage generated by a boost con-

verter. The boost converter was configured to con-

vert the 3 V battery voltage into a system voltage of

up to 3.7 V, allowing for a higher compliance volt-

age if needed. The unified approach offers the ad-

vantage of low circuit complexity, but achieves a low

compliance voltage only due to low maximum toler-

able supply voltage of the microcontroller and sen-

sors. In STELLA

+

, a Li-ion battery (A4X) operating

within a voltage range of 3 to 4.3 V is used as power

source. In order to overcome the compliance volt-

age limitations of STELLA, a dual-VDD approach

was applied, in which the control and stimulation unit

was split into separate voltage domains. The control

unit, including processors and sensors, is powered by

an LDO (Low-Dropout) regulator (TPS7A0228) that

provides a stable 2.8 V rail (V

DD1

). In contrast, the

stimulation unit is connected to a flexible buck-boost

converter topology. The boost (MAX17227A) and

buck (MAX38642A) converter are single ICs with

their outputs tied together. Each converter has an

EN pin that is used to enable or disable the outputs.

When disabled, the converter completely disconnects

the load. The enable signal (EN

DC/DC

) is driven by

the MSP430 and is routed directly to the boost con-

verter and is inverted (74LVC1G04) for the buck con-

verter. This configuration ensures that only one con-

verter is active at any given time, preventing con-

flicting voltage outputs. The output voltage of each

converter is controlled by an individual digital poten-

tiometer (AD5142A) in rheostat mode via I

2

C. This

topology enables the supply voltage for the stimula-

tion unit (V

DD2

) to be scaled either above or below the

battery voltage over a range of 2.5 V and 5.2 V. Com-

bined with the built-in self-test (BIST) that identifies

the maximum voltage at the end of the DBS pulse (see

Section 2.3.7), this method enables energy-efficient

adaptation of the supply voltage for the stimulation

unit according to the load impedance requirements.

2.3 Stimulation Unit

The stimulation unit is presented conceptually in

Fig. 2(a) and in detail in Fig. 2(c), while the level

translation design is shown in Fig. 2(b).

2.3.1 Multi-Modal Architecture

STELLA

+

features a multi-modal architecture ca-

pable of generating both charge-balanced current-

controlled and charge-balanced voltage-controlled

DBS pulses, both provided by clinical DBS de-

vices. The MSP430 controls a 2:1 analog switch

(TMUX1136) that enables the selection between the

stimulation modes for each channel. The current-

controlled mode is generally the preferred configura-

tion, as it maintains a constant current regardless of

load impedance changes (Kandadai et al., 2023; Hui

et al., 2020; Lempka et al., 2010). Therefore, this

mode is particularly optimized for energy efficiency

and is the primary focus of this section. In view of

current developments in other medical fields, such as

traumatology, the voltage-controlled mode may also

be suitable for other areas of application (Raben et al.,

2024; Nicksic et al., 2022; Klinder et al., 2024).

To this end, STELLA

+

incorporates a 10-bit DAC

(DAC6311) for each channel controlled by the SPI

(Serial Peripheral Interface) bus, enabling the genera-

tion of any required voltage-driven waveform for the

research objective. To ensure that only the AC com-

ponent of the DAC signal, which is typically required

in these application domains, contributes to the stimu-

lation, a blocking capacitor is incorporated that forms

a high-pass filter with the load. This capacitor is posi-

tioned behind the multiplexer to provide the current-

controlled mode with a safety feature for the DBS ap-

plication (see Section 2.3.7).

2.3.2 Generation of Current-Controlled DBS

Pulses

The dual-channel design for generating current-

driven DBS pulses builds on the previous STELLA

architecture, utilizing an MSP430 microcontroller to

precisely control the current amplitude, frequency and

pulse width of the DBS pulses. The dual-channel

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

76

Channel 1

L H

(I²C, SPI, EN

x

)

PWM

Ch1(H)

PWM

Ch2(H)

Protector

V

Bat

5.4 V

9.6 V

10 mA

V

DD2

V

DD1

V

DD2

Boost

Buck

LDO

Power Source

nRF

MSP

Charger

Channel 2

Level Translation

L

STIM

CTL

EN

Ch1(H)

IQ

1

I

Sel1

I

Out1

I

Out2

I

Sel2

IQ

2

EN

Ch2(H)

H

15 V

C

B1

C

B2

i

1

i

2

EN

DC/DC

PWM

(L)

PWM

(H)

I²C

PWM

Ch1(H)

PWM

Ch2(H)

V

DD2

V

DD2

V

DD2

(a) (b) (c)

DP

1

DP

3

||

DP

4

DP

5

||

DP

6

DP

2

H

L

V

DD1

V

DD2

10 MΩ

10 MΩ

SHDN

1(H)

V

C1(H)

V

Ref

V

C2(H)

SHDN

2(H)

OA

1

OA

2

Figure 2: Architecture of STELLA

+

. (a) Block diagram illustrating the concept of battery and power management. (b) Level

translation design. (c) Detailed circuitry of the stimulation unit for generating current-controlled and charge-balanced DBS

pulses (adapted from (Plocksties et al., 2021a)).

capability is enabled by a dedicated constant current

source (PSSI2021SAY) for each stimulation channel

which allows the current amplitude to be adjusted

individually. The assumption that a single current

source’s output will result in the half current am-

plitude by connecting the other microelectrode par-

allel to its output is invalid due to differing load

impedances for each channel, as is the case in (K

¨

olbl

et al., 2016). The differences in load impedance are

due to several factors, including the different conduc-

tivity values of white and grey matter (Gabriel and

Gabriel, 1996; Hasgall et al., 2022; Koessler et al.,

2017), the highly dynamic biological encapsulation

processes that surround the electrodes after insertion

(Evers et al., 2022; Lempka et al., 2009), and inherent

manufacturing variations in the electrodes themselves

(Payonk et al., 2025). Furthermore, it is not recom-

mended to achieve a current-controlled stimulation by

varying the resistor in series with a voltage source as

is the case in (de Haas et al., 2012), or by adjusting

the output voltage of a voltage source as is the case

in (Liu et al., 2017). First, these approaches require

frequent active readjustment due to the dynamic load,

which might be energy-intensive. Second, the result-

ing current amplitudes can only be considered con-

stant on a macroscopic time scale. At a microscopic

level, the system still behaves like a voltage source,

which cannot maintain a constant current during the

pulse duration due the capacitive component of the

impedance load (see (de Haas et al., 2012)), resulting

in only semi-current-controlled stimulation.

In STELLA

+

, both current sources (IQ

1

,IQ

2

) are

controlled by the MSP430’s PWM (Pulse-width mod-

ulation) signal, that carries the frequency and pulse

width information, resulting in synchronized DBS

pulses for both channels. Similar to STELLA, the

MSP430’s clock in STELLA

+

is sourced by an ex-

ternal 32,768 Hz crystal, thereby enabling the micro-

controller to operate in ultra-low power mode. Con-

sequently, the pulse width and frequency can be ad-

justed in approximately 30 µs increments. In or-

der to adjust the stimulation current of the previous

STELLA, a digital potentiometer in rheostat mode

in parallel with a fixed resistor is used to tailor the

highly non-linear output of the current source with

high resolution between 50 µA and 100 µA. However,

if higher stimulation currents with high accuracy were

required, the resistor had to be resoldered. In con-

trast, STELLA

+

employs two digital potentiometers

(AD5143) in parallel (DP

3

DP

4

, DP

5

DP

6

, all op-

erating in rheostat mode) for adjusting the stimula-

tion current of each channel, allowing high-resolution

adjustments above 100 µA without the need for hard-

ware modifications. Note that since the output current

of the used current source varies with supply voltage,

it must be calibrated across the entire supply voltage

range. The same applies to temperature, requiring the

output current to be calibrated under in vivo condi-

tions.

2.3.3 Compliance Voltage

Most existing stimulation devices for rodents are de-

signed for current-controlled stimulation, which en-

sures constant current delivery despite variations in

load impedance (see Table 1). Maintaining a constant

current requires sufficient compliance voltage to ac-

commodate the diverse range of electrode configura-

tions, stimulation parameters and electrode encapsu-

lation caused by the biological response. In the ex-

isting literature on DBS devices, it is frequently as-

sumed that the supply voltage of the current source is

equal to the maximum voltage that the current source

can provide for the load impedance. This assump-

tion is incorrect, as the internal resistance of a cur-

rent source leads to a voltage drop that reduces its

maximum output voltage. This voltage drop varies

depending on the type of current source, but is typ-

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

77

ically around 1 V. The current source’s supply volt-

age minus the internal voltage drop is called compli-

ance voltage. This consideration is especially impor-

tant for DBS devices operating with a current source’s

supply voltage in the region of 3 V (Plocksties et al.,

2021a; Fleischer et al., 2020; Grotemeyer et al., 2024;

Fluri et al., 2017; Kouzani et al., 2017). While these

devices typically feature a low current consumption,

their relatively low compliance voltage below 3 V in-

creases the risk that the constant current cannot be

maintained within the pulse width when using stan-

dard stimulation protocols and standard electrodes.

This can be especially critical when integrated mon-

itoring capabilities are lacking to check whether the

stimulation is in a valid range. In contrast, circuit de-

signs that allow for higher compliance voltages result

in significantly increased current consumption, even

reaching the mA range in some cases (Ewing et al.,

2013; Pinnell et al., 2018; Pinnell et al., 2015; K

¨

olbl

et al., 2016; Adams et al., 2019), which negatively

impacts the ratio between battery volume and run-

time. Furthermore, considering that typical rodent

stimulation protocols use stimulation currents of no

more than 100 µA for 60 µs (Reese et al., 2009; Ev-

ers et al., 2022; Leblois et al., 2010; Heerdegen et al.,

2021; Paap et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024), devices

operating at such high compliance voltages may be

regarded as oversized and consequently inefficient.

Using the bipolar microelectrode PI-SNEX-100 (Mi-

croprobes, Gaithersburg, USA), which is widely used

in rodent DBS studies, our ex vivo voltage measure-

ments in rodent brain tissue showed that the maxi-

mum voltage of the DBS pulse never exceeded 3.5 V

for a 100 µA/60 µs pulse with a frequency of 130 Hz.

STELLA

+

is designed for high energy efficiency

to facilitate long-term experiments with a low battery

volume while offering sufficient compliance voltage

up to 4.3 V to support the most common stimulation

setups in DBS research using rodent models (see Sec-

tion 3.2, 3.3).

2.3.4 Level Translation

Given the 2.8 V operating voltage of the MSP430

and the up to 5.2 V domain of the stimulation unit

in STELLA

+

, an appropriate level translation de-

sign is required that meets the requirements for ultra-

low power consumption. In order to level-shift the

low-voltage PWM signal (PWM

L

), which controls

the rectangular stimulation pulses, to the higher volt-

age rail (PWM

H

), a translation buffer (74LV1T34) is

used. Although the additional supply current in typ-

ical voltage translators increases significantly as the

input voltages diverge from the supply voltage, this

approach remains feasible due to very low duty cy-

cles encountered in DBS, such as a pulse width of

60 µs and a frequency of 130 Hz. A dedicated IC is

critical in this case as it ensures excellent signal in-

tegrity across the entire translation range required for

the sharp rise and fall time of the rectangular wave-

form.

All other signals, including the I

2

C bus, SPI bus

and EN signals, are level translated using n-channel

MOSFETs (CSD15380F3) together with pull-up re-

sistors, allowing reliable communication between the

voltage domains. For unidirectional operation, low-

to-high translation is achieved by a pull-up resistor at

the high side, while high-to-low communication uti-

lizes a pull-up at the low side. For bidirectional com-

munication, as required by the I

2

C, pull-up resistors

are implemented on both sides.

2.3.5 Charge Balancing

Any system designed for the electrical stimulation

of tissue must keep the voltage across the working

and counter electrode within the safe electrochemical

window to avoid harmful byproducts to the surround-

ing tissue. Since biological tissue is mainly composed

of water, exceeding a certain voltage threshold leads

to the electrolysis of water (Boehler et al., 2020).

This irreversible process can cause tissue damage due

to the formation of oxygen and hydrogen gases, along

with significant pH changes (Boehler et al., 2020;

Huang et al., 2001). In the scenario of DBS, each

stimulation pulse charges the double-layer capaci-

tance that is formed at the electrode-tissue interface.

It is critical to properly discharge this capacitance

between pulses to prevent charge accumulation over

time, ensuring that no sustained DC offset above the

decomposition voltage of water can develop.

To address this, STELLA

+

uses the established

passive charge balancing method by connecting the

stimulation electrode to ground through an adjustable

resistor, similar to STELLA. However, this method

has been slightly modified for STELLA

+

by using a

fast-switching n-channel MOSFET instead of an ac-

tive switching IC, resulting in negligible power con-

sumption of this method. This n-channel MOSFET is

controlled by the high-voltage PWM signal for each

channel (PWM

Ch1(H)

, PWM

Ch2(H)

). During the pulse-

off phase, the MOSFET is activated, creating a dis-

charge path for the double-layer capacitor. During

the pulse-on phase, it enters the high impedance state,

preventing interference with the stimulation pulse.

The passive charge balancing approach induces a cur-

rent reversal pulse. Without an additional resistor, the

peak value of the reversal pulse depends on the DBS

voltage and current value at the end of the pulse as

well as the value of the electrolyte resistance (access

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

78

resistance). The larger the peak value, the more it

could counteract the desired physiological effect of

the stimulation impulse (Merrill et al., 2005). There-

fore, a digital potentiometer (AD5143, 100 kΩ) in

rheostat mode is used in the discharge path of each

channel to reduce this peak value (DP

1

, DP

2

). Note

that the double-layer capacitor must be fully dis-

charged before the next pulse is generated, as other-

wise control over the electrode voltage will be lost.

The time required for full discharge should include a

sufficient safety margin to account for the various bi-

ological processes influencing the load impedance.

2.3.6 Independent Channel Control

While STELLA was developed for the simultaneous

control of two channels, the new design offers the op-

portunity to activate or deactivate each DBS chan-

nel independently. This is achieved by connecting

the high-voltage PWM signal (PWM

H

) to two NAND

gates, with the other input of each gate connected to

a level-shifted EN signal (EN

Ch1(H)

, EN

Ch2(H)

) con-

trolled by the MSP430. This feature allows for re-

duced current consumption by deactivating the un-

used channel in unilateral operation, which is of

special importance in unilateral disease models, e.g.

the 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease

(Ungerstedt, 1968). Furthermore, in the case of adap-

tive DBS (aDBS) it enables individual on-off control

for both channels simply by switching the enable sig-

nals. The effectiveness of the on-off control scheme

was demonstrated in the study by (Evers et al., 2024).

2.3.7 Safety and Reliability

The stimulation unit includes a DC blocking capaci-

tor of 20 µF placed in series with both current sources

(C

B1

, C

B2

). This capacitor acts as a safety measure for

the subject, preventing high faradaic currents if a sus-

tained, high DC voltage occurs at the electrode in the

event of a fault. However, it has been demonstrated

that even when perfectly charge-balanced stimulation

is applied, the blocking capacitor will generate an off-

set voltage at the electrode-tissue interface (van Don-

gen and Serdijn, 2016). To prevent the offset voltage

potentially exceeding the water window, a high-ohmic

resistance of 10 MΩ was placed in parallel to the load

impedance for each channel. This allows an effective

discharge path for the imbalanced charge, contribut-

ing to minimizing the offset voltage (see Section 3.2).

Furthermore, the 10 MΩ resistor has a negligible im-

pact on the stimulation current. For typical stimula-

tion currents above 50 µA that require the maximum

current source’s output voltage, this would result in a

reduction of the stimulation current of only less than

1 %.

In DBS studies including rodents, typical defects

such as shorted or open electrodes as well as an ex-

cessive load impedance are frequently encountered

(Plocksties et al., 2021a; Plocksties et al., 2022). If

these issues remain undetected, they can have a con-

siderable impact on DBS experiments, as they have

the potential to confound the experimental results and

conclusions. Particularly when using backpacks or

head-mounted DBS systems, the failure rate is con-

siderable (Plocksties et al., 2021a). Therefore, it is

crucial to integrate a method that reliably detects these

problems. Similar to STELLA, STELLA

+

incorpo-

rates a built-in self-test (BIST) that monitors and re-

ports such issues. In a nutshell, the maximum voltage

at the end of the DBS pulse is determined by gradu-

ally lowering the reference voltage at the inverting in-

put of a comparator. As a slight improvement over the

previous version, a dedicated 10-bit DAC (DAC6311)

is used for generating the reference voltage (V

Ref

) via

SPI instead of an 8-bit digital potentiometer, effec-

tively increasing the accuracy of this measurement.

2.4 Battery Management

The circuitry of STELLA

+

is designed for a recharge-

able Li-ion battery as power source, replacing CR or

SR button cells commonly used in existing rodent

stimulators. This eliminates the need for frequent

battery replacement. Additionally, the proposed

circuit design enables recharging the battery directly

via the electrode leads. This dual functionality

is particularly advantageous for fully implantable

stimulators, where the battery typically cannot be

replaced or recharged without damaging the encap-

sulation. The battery management of STELLA

+

is

conceptually presented in Fig. 2(a).

2.4.1 Battery Protection

When using Li-ion batteries, following the safety pro-

tocols is essential, especially when implanted into liv-

ing beings. Therefore, the circuit design has to con-

tain adequate safety mechanisms to safeguard Li-ion

batteries against overcharge, overdischarge, overcur-

rent and short-current. To address these safety re-

quirements, we used a battery management IC (S-

82A1ACA-I6T1U) in combination with two exter-

nal n-channel MOSFETs resulting in disconnecting

the GND potential if any value falls outside the

valid range specified in the technical handbook from

VARTA (VARTA, 2019). Falling below the overdis-

charge voltage of 3 V, this IC transitions to a power-

down mode wherein it consumes 50 nA only, thus

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

79

preventing damage to the cell through continued dis-

charge. A second layer of protection is provided

by VARTA’s vent holes integrated into the battery

(VARTA, 2019). These vents ensure that any excess

pressure is released to guarantee safety. For this, it

must be ensured that the encapsulation of the device

provides sufficient space for expansion.

2.4.2 Battery Recharge

For recharging the A4X, a battery charger IC

(BQ25100A) is used, configured with a charging limit

of 4.3 V and a charge current of 10 mA. To allow

the cable that transmits the stimulation signal to the

electrode to also serve as a path for supplying power

to the input of the charger IC, a bilateral TVS diode

(SP0201B-ELC-01UTG) with a breakdown voltage

of ±9.6 V/1 mA is used. This low-capacitance diode

prevents interference between the charger IC and the

stimulation output. As the maximum voltage that

the DBS pulse reaches is 4.3 V, this breakdown volt-

age is far below this value. Considering the volt-

age drop across the TVS diode with a charge cur-

rent of 10 mA, the power source has to output approx.

15 V to provide a sufficiently high input voltage for

the charger IC. A blocking capacitor in series to the

current source (C

B1

), already used for protecting the

brain tissue in a failure event, serves as high-voltage

protection for the current source and the circuitry for

the built-in self-test.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Device Specifications

The PCBs are designed in a six-layer configuration

with a high wiring density per unit area, enabling a

small footprint despite a high IC package area. The

manufactured boards measure 21x14.5 mm with a cir-

cular cut-out of 9.5 mm diameter to accommodate the

battery for the overall system in a space-saving man-

ner (see Fig. 3). When the PCBs are stacked, the total

height is 4 mm, matching the height of the battery.

The total PCB volume, calculated as 21x14.5x4 mm

minus the volume of the cut-out, results in 935 mm

3

.

The PCB weight is 1.2 g, while the complete device

including the battery weighs 2.1 g. When combined

with the reliable and compact encapsulation method

presented in (Plocksties et al., 2021b), for example,

the device specifications might be highly suitable for

fully subcutaneous implantation in small rodents.

Figure 3: STELLA

+

demonstrated on graph paper, featur-

ing the PCB stack and Li-ion battery.

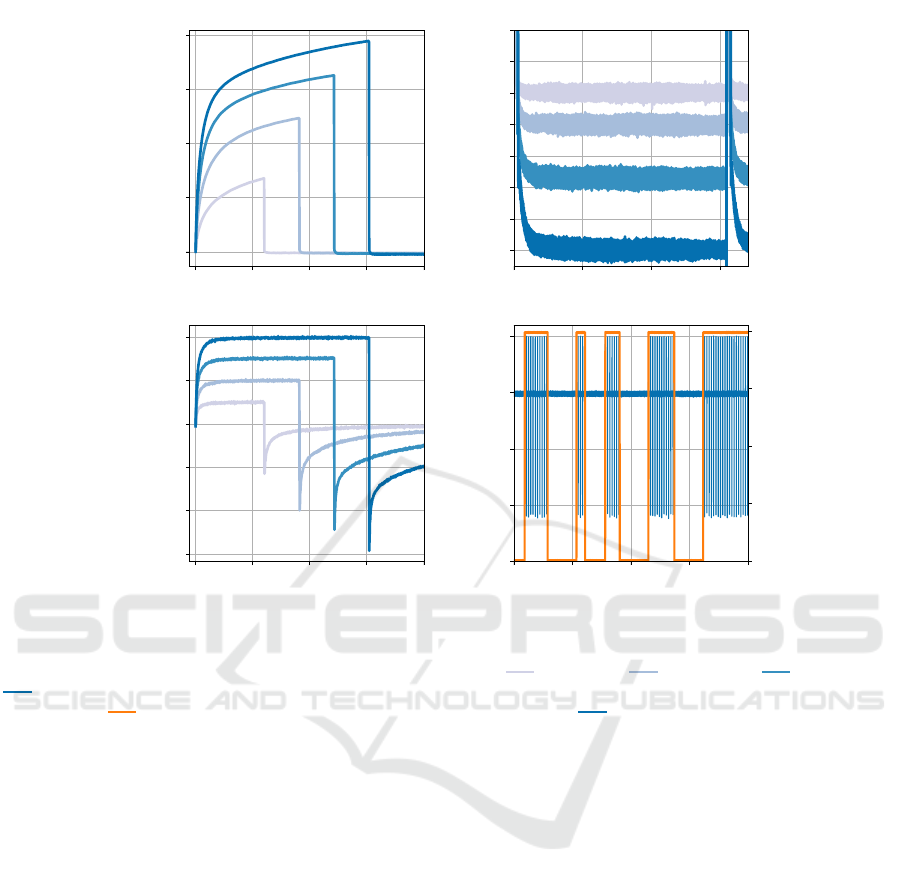

3.2 In Vitro Characterization of the

Stimulation Unit

3.2.1 Measurement Setup

The performance of the stimulation unit of STELLA

+

for current-controlled DBS was evaluated in an in

vitro setting. A PI-SNEX-100 microelectrode was

connected to one channel of STELLA

+

and im-

mersed in a NaCl conductivity standard solution of

0.199 0.002 S m

−1

at 25 °C. This conductivity was

chosen because it lies within the range of reported

conductivity values for white and grey matter (Gabriel

and Gabriel, 1996; Hasgall et al., 2022; Koessler

et al., 2017; Akhtari et al., 2006), considering the

relevant frequency range derived from the frequency

spectrum of the DBS signal (Badstuebner et al., 2017;

Gimsa et al., 2005).

For the measurements presented in Fig. 4(a)-(c),

the current amplitude was increased by 50 µA and

the pulse width was increased by 30 µs simultane-

ously, starting with 50 µA/60 µs and ending with

200 µA/150 µs. The frequency was set to 130 Hz

for all settings. For the measurement presented in

Fig. 4(d), STELLA

+

was programmed to a random

on-off sequence of current-controlled DBS pulses

with a stimulation set to 100 µA, 60 µs and 130 Hz.

For all stimulation settings, passive charge balanc-

ing is conducted with a minimal resistance in the dis-

charge path (in the lower hundreds Ω-range), which

can be neglected since the electrolyte resistance is

much higher in this case. The change in stimulation

parameters was initiated by a magnet that triggered

the magnetic sensor. Current and voltage recordings

were performed using the CX3324A waveform ana-

lyzer with a sample rate of 10 MSa/s.

The voltage measurements were conducted by

connecting the probe tip to the channel output and the

probe ground lead to ground. Current measurements

were taken by placing the current probe in series, with

the positive terminal connected to the channel output

and the negative terminal to the load. In this setup, the

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

80

stimulation pulses are recorded in the positive range,

in contrast to the negative range in which the signals

are usually presented in the literature as an indication

of the commonly used cathodic stimulation. The rep-

resentation in the positive range is only intended for

clearer visualization of the signals in an ‘upright’ for-

mat and is not related to the polarity of the electrode

contacts.

Furthermore, the voltage recordings were per-

formed using a high-speed operational amplifier with

a high input impedance (OPA810, 12 GΩ 2 pF in

common mode) in a unity-gain buffer configuration.

This setup is required especially for the offset voltage

measurements presented in Fig. 4(c) because the rela-

tively low input resistance of 1 or 10 MΩ for a typical

probe would otherwise have provided an external dis-

charge path for the accumulated charge, which would

have distorted the offset voltage results.

3.2.2 Results

The voltage recordings in Fig. 4(a) exhibited the

characteristic waveform associated with current-

controlled stimulation. The voltage increases rapidly

initially, representing the voltage drop across the

electrolyte resistance, and is followed by the volt-

age drop across the electrode-electrolyte interface

(Boehler et al., 2020). No offset voltage can be ob-

served in the volt range. Only a closer examination in

the millivolt range reveals its presence (see Fig. 4(c)).

The current recordings in Fig. 4(b) demonstrated

sharp rising and falling edges, as well as a precise

constant current throughout the pulse width across all

settings. The end of each pulse is followed by the re-

versal pulse that results from shorting the electrode

to ground. Without the use of an additional resis-

tor in the discharge path, the reversal pulses show

peak values that have slightly higher magnitudes than

the stimulation current, with a maximum of approx.

100 µA. After the peak, the current drops exponen-

tially, with the double-layer capacitor almost com-

pletely discharged after five time constants, which

are reached in less than one millisecond for all set-

tings. For typical stimulation frequencies, this short

discharge time enables the use of a resistance in the

discharge path in order to reduce the peak value of

the reversal pulse to at least the same magnitude as

the stimulation current, a value commonly used in ac-

tive charge balancing (symmetric biphasic) (Parastar-

feizabadi and Kouzani, 2017).

The voltage recordings presented in Fig. 4(c) in-

dicate the offset voltage caused by the blocking ca-

pacitor. After the start of stimulation, the offset volt-

age shifted towards more negative values over time

and the observations were continued until stabiliza-

tion, which occurred after approximately 5 minutes.

The figure shows the offset voltage in the steady state

between two DBS pulses for each stimulation param-

eter setting. This offset can be approximated as con-

sistent DC bias, as the DBS pulse is short relative to

the pulse-off phase and the offset voltage reaches its

value rapidly after the DBS pulse. Furthermore, the

figure shows that the magnitude of the offset voltage

increases with higher injected charge, which is ex-

plained in (van Dongen and Serdijn, 2016). For the

50 µA/60 µs pulse, the offset voltage is recorded as

the smallest negative value at −25 mV, whereas the

200 µA/150 µs pulse results in the most negative off-

set voltage of −70 mV. Considering the theoretical

minimum potential difference of 1.23 V needed for

water splitting (Lamy and Millet, 2020) as the critical

limit for the developed DC bias absolute value, the

measured offset voltages are significantly lower for

all settings. This high safety margin is achieved by

the integrated 10 MΩ resistor in parallel to the load,

which provides an effective discharge path for the im-

balanced charge.

The Fig. 4(d) presents a randomly timed DBS on-

off scheme. The stimulation pulses show a precise

stimulation current of 100 µA, accompanied by the

reversal pulses resulting from the charge balancing

method. The on-off pattern is achieved by toggling

the enable signal (EN

Ch1(H)

) at the input of the AND

gate of the first channel. Moreover, the enable sig-

nal switches between 0 V and 4 V, demonstrating the

proper functioning of the level translation (see Sec-

tion 2.3.4). The measurements show that STELLA

+

effectively enables the implementation of this aDBS

control option.

3.3 Current Consumption vs.

Compliance Voltage

The compliance voltage and corresponding current

consumption are important performance metrics for a

neurostimulator that delivers current-controlled stim-

ulation pulses. To investigate this relationship for

STELLA

+

, the following measurement setup was de-

signed.

3.3.1 Measurement Setup

The current waveform analyzer CX3324A was

placed in series with an external power supply and

STELLA

+

. The power supply was set to 3.7 V, which

is the nominal voltage of the A4X series. The current

consumption was then measured for the supply volt-

age at a minimum of 2.5 V and a maximum of 5.2 V

provided by the buck-boost topology. The CX3324A

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

81

0 50 100 150 200

Time (µs)

0

1

2

3

4

Voltage (V)

0.0 2.5 5.0 7.5

Time (ms)

0

-10

-20

-30

-40

-50

-60

-70

Voltage (mV)

0 50 100 150 200

Time (µs)

−300

−200

−100

0

100

200

Current (µA)

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8

Time (s)

−300

−200

−100

0

100

Current (µA)

0

1

2

3

4

Voltage (V)

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 4: Performance of STELLA

+

in delivering current-controlled stimulation pulses via a bipolar PI-SNEX-100 immersed

in a 0.199 S m

−1

saline solution. The figure illustrates recordings of (a) voltage and (b) current of the DBS pulse, as well as

(c) the offset voltage in steady state at various stimulation parameters: 50 µA/60 µs, 100 µA/90 µs, 150 µA/120 µs,

200 µA/150 µs, all at a frequency of 130 Hz. Additionally, (d) a randomly timed DBS on-off scheme controlled by the

enable signal ( ) is shown, with stimulation set to 100 µA, 60 µs and 130 Hz ( ).

sampled the current at 1 MSa/s and the final result

was calculated by averaging the measurement over

a period of 20 s. Furthermore, both measurements

were performed in DBS-on mode, using the follow-

ing stimulation parameters: bilateral stimulation with

a load of 10 kΩ respectively, 100 µA current ampli-

tude, 60 µs pulse width and 130 Hz frequency. Finally,

the compliance voltage was determined as the voltage

at which the adjusted constant current started to drop,

which was observed with an oscilloscope. This was

typically noticed when the voltage of the DBS pulse

exceeded the level that was 0.9 V lower than the cur-

rent source’s supply voltage.

3.3.2 Results

STELLA

+

achieves at its minimum compliance volt-

age of 1.6 V a current consumption of 8.9 µA and at

its maximum compliance voltage of 4.3 V a current

consumption of 25.1 µA. In comparison, the previ-

ous STELLA version achieved a maximum compli-

ance voltage of 2.8 V with 12.2 µA.

The results show that STELLA

+

provides a higher

compliance voltage than its predecessor, enabling a

wider range of stimulation setups while still main-

taining an ultra-low current consumption for long-

term studies. When the maximum compliance volt-

age is required, STELLA

+

still provides 6.8 weeks of

stimulation using the CP9440 A4X battery (29 mAh),

which is sufficient for most rodent DBS studies.

3.4 Comparison of Features with the

State-of-the-Art

To compare the results with other DBS devices de-

signed for rodent studies, a review of the relevant lit-

erature was conducted. ASIC designs were excluded

from the comparison due to their specialized and pro-

prietary nature, e.g. (Arfin et al., 2009). In contrast,

DBS devices using off-the-shelf discrete components

allow the research community to replicate the designs

and customize them to their experimental needs.

Table 1 presents the feature set of existing ro-

dent DBS devices, organized by publication year

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

82

Table 1: Comparison of key features in existing rodent DBS devices designed with off-the-shelf components.

DBS

device

PCB Volume

category

Device

control

Data output

technology

Provided device/

physiological data

Device

Mounting

Stimulation

properties

Extra

features

Radio frequency (RF)

Reed switch/Magnetic sensors

Physical switch/potentiometer

Optical

Radio frequency (RF)

Optical

High-accuracy temperature

3-axis acceleration

Local field potentials (LFPs)

Load impedance (OOR )

Battery voltage (OOR )

Stimulation on/off

Stimulation protocol

Head

Back

Implant

Dual-channel

Current-controlled

Voltage-controlled

Charge-balanced

Adaptive DBS capabilities

SW-adjustable stim. parameters

Auto-set compliance voltage

On-board battery recharge

Battery-powered

STELLA+ L - - - - -

Grotemeyer2024 VL - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - - - - -

STELLA2021 VL - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Tala2021 H - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Fleischer2020 VL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Adams2019 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Alpaugh2019 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

Schulz2019 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# -

Pinnell2018 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

Fluri2017 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Liu2017 M - - - - - - - - - - - G# - - G# - -

Kouzani2017 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

Parastarfeizabadi2016 VL - - - - - - - G# - - - - - - - - G# - -

K

¨

olbl2016 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - - - -

Pinnell2015 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Acosta2015 VL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Hentall2013 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Ewing2013 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Haas2012 L - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - - G# - -

Forni2012 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

Harnack2008 M - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

Battery-free (Wireless power transfer)

Burton2021 VL - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Heo2015 M - - - - - - - - - - G# - - - G# - -

Millard2007 L - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - G# - -

= Feature is implemented; G# = Feature is partially implemented; - = Feature is not implemented;

= Out of range indication; = Optical wireless communication provided (for STELLA2021 refer to (Koschay et al., 2022));

= Inadequate current source design (see 2.3.2); = Inadequate dual-channel design (see 2.3.2);

= Constant current adjustment manually via potentiometer; = Partial subcutaneous implant only;

VL: Very Low ( 500 mm

3

), L: Low (500 1000 mm

3

), M: Medium (1000 5000 mm

3

), H: High ( 5000 mm

3

)

and divided into two classes: battery-powered and

battery-free. Battery-powered devices operate by us-

ing batteries, while battery-free devices depend solely

on wireless power transfer (WPT) from an external

source. Note that WPT requires specialized cages that

can lead to unreliable operation if coils are misaligned

due to the animal movement, and prevent essential be-

havioral experiments like the Morris water maze (Mil-

lard and Shepherd, 2007; Burton et al., 2021; Evers

et al., 2022).

The features identified in the literature were orga-

nized into categories, which are analyzed in the fol-

lowing.

PCB Volume Category: The PCB volume is of

crucial importance as it dictates the mounting options

and overall impact on the animal. The DBS devices

were categorized based on their PCB volume into four

classes (see Table 1). In cases where the PCB volume

was not indicated, it was estimated from the photo-

graphic scale. The volume specifications are based

on earlier work and were expanded in this study by

further DBS devices (Plocksties et al., 2021a).

STELLA

+

falls into the ‘low’ category as it has

been specifically designed to allow fully subcuta-

neous implantation in small rodents.

Device Control: Radio frequency communication is

considered the most effective control method as it al-

lows to modify a wide range of device parameters

without disturbing the animal. However, the require-

ment for considerable PCB area, the need for higher

power consumption and the complexity of RF de-

sign have limited its widespread use. The most com-

monly used control method involves magnetic sen-

sors, which are mainly used to trigger specific device

functions, such as integrated self-tests. Some stim-

ulators also incorporate physical elements, including

switches and potentiometers. However, these compo-

nents are large as they have to be operated manually,

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

83

leading to a poor functionality-to-size ratio. Another

control mechanism involves transmitting light pulses

to a photodiode. However, this approach is challeng-

ing due to the movement of the animals and is cur-

rently only used in one stimulator (Heo et al., 2015).

In contrast, STELLA

+

does not include any opti-

cal or physical elements for its control. Instead, it uses

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), which enables detailed

configuration of the device parameters from a great

distance to the animal. To ensure redundancy, the

device includes a magnetic sensor for essential tasks,

like turning the stimulation on/off.

Data Output Technology: RF communication en-

ables high data rates, which are required for the wire-

less transmission of physiological data, such as local

field potentials and accelerometer data. However, due

to the aforementioned obstacles associated with RF

modules, optical data transmission is most commonly

used in DBS devices. For this, LEDs are utilized that

operate either in the visible spectrum or in the infrared

range (IR), with simple blinking patterns indicating

device information, e.g. low battery voltage alerts.

STELLA

+

employs the nRF52833 microcon-

troller, which supports BLE for efficient transmis-

sion of device and physiological data. Additionally,

STELLA

+

features two visible LEDs (red and green)

and an IR LED for convenient indication of device

information.

Provided Device/Physiological Data: Most DBS

devices provide only basic device-specific data, such

as low battery voltage alerts and the stimulation status

(on/off). However, the indication of out-of-range load

impedance is rarely provided, despite its significance

for replicable experiments. In addition, only two DBS

devices allow the transmission of the applied stimu-

lation protocol, which is important for verifying that

the stimulation parameters are set correctly, especially

when they have been changed. Moreover, only one

device is able to transmit physiological data wire-

lessly, specifically local field potentials (LFPs) (Pin-

nell et al., 2015). The other device that enables the

readout of LFPs, processes this data entirely on-board

(Parastarfeizabadi et al., 2016).

STELLA

+

is the first DBS device for rodents that

incorporates a high-accuracy temperature sensor and

a 3-axis accelerometer. The accelerometer enables the

investigation of movement profiles, which could rep-

resent a potential biomarker for adaptive DBS, while

requiring significantly less PCB area and energy com-

pared to traditional LFP recordings. Additionally,

STELLA

+

provides data on the battery voltage, the

on/off status of the stimulation, the applied stimu-

lation protocol, and whether the load impedance is

within a valid range. All device and physiological

data can be transmitted wirelessly via BLE.

Device Mounting: Most DBS devices are designed

for head or backpack mounting, which limits animal

mobility and often leads to higher failure rates. Fully

implantable stimulators overcome these problems, but

are more challenging to realize due to their high de-

gree of miniaturization and waterproof encapsulation.

STELLA

+

is characterized by a small stimulator-

battery volume, making it ideal for subcutaneous im-

plantation in small rodents. Its flat profile also sup-

ports the healing process by reducing tension on the

overlying skin.

Stimulation Properties: Most DBS devices are

primarily designed with charge-balanced current-

controlled stimulation, while voltage-controlled stim-

ulation is rarely implemented. Furthermore, the ma-

jority of DBS devices are designed for single-channel

stimulation, which limits DBS to one hemisphere. A

dual-channel design is less common, although a sec-

ond channel is essential for studying bilateral DBS.

In contrast, STELLA

+

provides the ability to se-

lect between charge-balanced current-controlled and

charge-balanced voltage-controlled stimulation for

one or two channels. Moreover, STELLA

+

features

aDBS capabilities through on-off switching of stim-

ulation based on feedback data from a 3-axis ac-

celerometer. This functionality is only supported by

two other stimulators, which differ in that they use

LFPs as feedback data (Pinnell et al., 2015; Paras-

tarfeizabadi et al., 2016). Additionally, STELLA

+

includes a powerful processing core that enables on-

board processing capabilities for complex algorithms.

Extra Features: DBS devices often provide the extra

feature of adjusting the stimulation parameters cur-

rent amplitude, frequency and pulse width via soft-

ware. In cases where this feature is only partially

available, the adjustment of the current amplitude is

typically limited to the use of an analog potentiome-

ter or the resoldering of a resistor.

With STELLA

+

, all stimulation parameters can

be configured via software and also adjusted wire-

lessly via BLE during the experiment. Additionally,

the automatic adjustment of the compliance voltage

improves energy efficiency and is exclusive to both

STELLA

+

and its predecessor. Finally, STELLA

+

supports on-board battery recharging via electrode

leads, an extra feature that is also present in only one

other DBS device via wireless power transfer.

In summary, it can be concluded from Table 1

that STELLA

+

has a wider and unique feature set

compared with other state-of-the-art DBS devices for

rodent DBS.

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

84

4 CONCLUSION

We introduce STELLA

+

, an innovative research plat-

form designed for advanced DBS studies in freely-

moving rodents. This paper serves as a starting point

for future in vivo DBS studies in rodents and primar-

ily focuses on the specifications and capabilities of

STELLA

+

. The initial results highlight STELLA

+

’s

compact design, energy-efficient architecture, inte-

grated system monitoring and accurate generation of

current-controlled and charge-balanced DBS pulses,

which together form the basis for effective preclini-

cal DBS research. Equipped with multiple sensors,

a powerful processing unit and a Bluetooth Low En-

ergy module, STELLA

+

enables research into closed-

loop stimulation. Compared to its predecessor and

other state-of-the-art DBS devices, STELLA

+

offers

unprecedented experimental flexibility (see Table 1),

rendering it an essential tool for both traditional and

adaptive DBS research in rodents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

(DFG, German Research Foundation) - SFB 1270/1,2

- 299150580. Our special thanks go to VARTA for

providing Li-ion button cells for research purposes

and to Uwe Kn

¨

upfer for his manufacturing support.

REFERENCES

Adams, S. D., Bennet, K. E., Tye, S. J., Berk, M.,

and Kouzani, A. Z. (2019). Development of a

miniature device for emerging deep brain stimulation

paradigms. PLOS ONE, 14(2):e0212554.

Akhtari, M., Salamon, N., Duncan, R., Fried, I., and Math-

ern, G. (2006). Electrical conductivities of the freshly

excised cerebral cortex in epilepsy surgery patients;

correlation with pathology, seizure duration, and dif-

fusion tensor imaging. Brain Topography, 18:281–

290.

Arfin, S. K., Long, M. A., Fee, M. S., and Sarpeshkar,

R. (2009). Wireless neural stimulation in freely be-

having small animals. Journal of neurophysiology,

102(1):598–605.

Badstuebner, K., Gimsa, U., Weber, I., Tuchscherer, A., and

Gimsa, J. (2017). Deep brain stimulation of hemi-

parkinsonian rats with unipolar and bipolar electrodes

for up to 6 weeks: Behavioral testing of freely moving

animals. Parkinson's Disease, 2017:1–18.

Boehler, C., Carli, S., Fadiga, L., Stieglitz, T., and As-

plund, M. (2020). Tutorial: guidelines for standard-

ized performance tests for electrodes intended for neu-

ral interfaces and bioelectronics. Nature protocols,

15(11):3557–3578.

Burton, A., Won, S. M., Sohrabi, A. K., Stuart, T., Amirhos-

sein, A., Kim, J. U., Park, Y., Gabros, A., Rogers,

J. A., Vitale, F., et al. (2021). Wireless, battery-free,

and fully implantable electrical neurostimulation in

freely moving rodents. Microsystems & nanoengi-

neering, 7(1):62.

de Haas, R., Struikmans, R., van der Plasse, G., van

Kerkhof, L., Brakkee, J. H., Kas, M. J., and West-

enberg, H. G. (2012). Wireless implantable micro-

stimulation device for high frequency bilateral deep

brain stimulation in freely moving mice. Journal of

neuroscience methods, 209(1):113–119.

D

´

ıez-Solinska, A., Vegas, O., and Azkona, G. (2022). Re-

finement in the european union: a systematic review.

Animals, 12(23):3263.

Evers, J., Orłowski, J., Jahns, H., and Lowery, M. M.

(2024). On-off and proportional closed-loop adaptive

deep brain stimulation reduces motor symptoms in

freely moving hemiparkinsonian rats. Neuromodula-

tion: Technology at the Neural Interface, 27(3):476–

488.

Evers, J., Sridhar, K., Liegey, J., Brady, J., Jahns, H., and

Lowery, M. (2022). Stimulation-induced changes at

the electrode–tissue interface and their influence on

deep brain stimulation. Journal of Neural Engineer-

ing, 19(4):046004.

Ewing, S. G., Lipski, W. J., Grace, A. A., and Winter,

C. (2013). An inexpensive, charge-balanced rodent

deep brain stimulation device: A step-by-step guide

to its procurement and construction. Journal of Neu-

roscience Methods, 219(2):324–330.

Fleischer, M., Endres, H., Sendtner, M., and Volkmann, J.

(2020). Development of a fully implantable stimula-

tor for deep brain stimulation in mice. Frontiers in

Neuroscience, 14.

Fluri, F., M

¨

utzel, T., Schuhmann, M. K., Krsti

´

c, M., En-

dres, H., and Volkmann, J. (2017). Development of a

head-mounted wireless microstimulator for deep brain

stimulation in rats. Journal of Neuroscience Methods,

291:249–256.

Forni, C., Mainard, O., Melon, C., Goguenheim, D., Goff,

L. K.-L., and Salin, P. (2012). Portable microstimula-

tor for chronic deep brain stimulation in freely moving

rats. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 209(1):50–57.

Gabriel, C. and Gabriel, S. (1996). Compilation of the di-

electric properties of body tissues at rf and microwave

frequencies.

Gimsa, J., Habel, B., Schreiber, U., van Rienen, U., Strauss,

U., and Gimsa, U. (2005). Choosing electrodes for

deep brain stimulation experiments–electrochemical

considerations. Journal of Neuroscience Methods,

142(2):251–265.

Grotemeyer, A., Petschner, T., Peach, R., Hoehl, D.,

Knauer, T., Thomas, U., Endres, H., Blum, R., Sendt-

ner, M., Volkmann, J., and Ip, C. W. (2024). Standard-

ized wireless deep brain stimulation system for mice.

npj Parkinson’s Disease, 10(1).

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

85

Hamani, C. and N

´

obrega, J. N. (2010). Deep brain stimula-

tion in clinical trials and animal models of depression.

European Journal of Neuroscience, 32(7):1109–1117.

Harmsen, I. E., Elias, G. J., Beyn, M. E., Boutet, A., Pan-

choli, A., Germann, J., Mansouri, A., Lozano, C. S.,

and Lozano, A. M. (2020). Clinical trials for deep

brain stimulation: Current state of affairs. Brain Stim-

ulation, 13(2):378–385.

Hasgall, P., Di Gennaro, F., Baumgartner, C., Neufeld, E.,

Lloyd, B., Gosselin, M., Payne, D., Klingenb

¨

ock, A.,

and Kuster, N. (2022). It’is database for thermal and

electromagnetic parameters of biological tissues, ver-

sion 4.1.

Heerdegen, M., Zwar, M., Franz, D., H

¨

ornschemeyer, M. F.,

Neubert, V., Plocksties, F., Niemann, C., Timmer-

mann, D., Bahls, C., van Rienen, U., et al. (2021).

Mechanisms of pallidal deep brain stimulation: Al-

teration of cortico-striatal synaptic communication in

a dystonia animal model. Neurobiology of Disease,

154:105341.

Heo, M. S., Moon, H. S., Kim, H. C., Park, H. W., Lim,

Y. H., and Paek, S. H. (2015). Fully implantable deep

brain stimulation system with wireless power trans-

mission for long-term use in rodent models of parkin-

son’s disease. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Soci-

ety, 57(3):152–158.

Huang, C. Q., Carter, P. M., and Shepherd, R. K. (2001).

Stimulus induced ph changes in cochlear implants: an

in vitro and in vivo study. Annals of biomedical engi-

neering, 29:791–802.

Hui, D., Murgai, A. A., Gilmore, G., Mohideen, S. I., Par-

rent, A. G., and Jog, M. S. (2020). Assessing the effect

of current steering on the total electrical energy deliv-

ered and ambulation in parkinson’s disease. Scientific

Reports, 10(1):8256.

Jakobs, M., Fomenko, A., Lozano, A. M., and Kiening,

K. L. (2019). Cellular, molecular, and clinical mech-

anisms of action of deep brain stimulation—a sys-

tematic review on established indications and outlook

on future developments. EMBO molecular medicine,

11(4):e9575.

Kandadai, R. M., Meka, S. S., Kola, S., Alugolu, R., and

Borgohain, R. (2023). Constant current versus con-

stant voltage dbs stimulators—changing trend. Annals

of Indian Academy of Neurology, 26(4):368–369.

Klinder, A., Moews, F., Ziebart, J., Su, Y., Gabler, C.,

Jonitz-Heincke, A., van Rienen, U., Ellenrieder, M.,

and Bader, R. (2024). Effects of electrical stim-

ulation with alternating fields on the osseointegra-

tion of titanium implants in the rabbit tibia-a pilot

study. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnol-

ogy, 12:1395715.

Koessler, L., Colnat-Coulbois, S., Cecchin, T., Hofmanis,

J., Dmochowski, J. P., Norcia, A. M., and Maillard,

L. G. (2017). In-vivo measurements of human brain

tissue conductivity using focal electrical current in-

jection through intracerebral multicontact electrodes.

Human brain mapping, 38(2):974–986.

Koschay, M., Richter, H., Statz, M., Kober, M., Puschmann,

J., Plocksties, F., Storch, A., K

¨

uhn, V., and Timmer-

mann, D. (2022). Case-study on visible light com-

munication for implant monitoring. In 2022 IEEE

Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (Bio-

CAS), pages 275–279. IEEE.

Kouzani, A. Z., Kale, R. P., Zarate-Garza, P. P., Berk,

M., Walder, K., and Tye, S. J. (2017). Validation of

a portable low-power deep brain stimulation device

through anxiolytic effects in a laboratory rat model.

IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabili-

tation Engineering, 25(9):1365–1374.

K

¨

olbl, F., N’Kaoua, G., Naudet, F., Berthier, F., Fag-

giani, E., Renaud, S., Benazzouz, A., and Lewis,

N. (2016). An embedded deep brain stimulator for

biphasic chronic experiments in freely moving ro-

dents. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and

Systems, 10(1):72–84.

Lamy, C. and Millet, P. (2020). A critical review on the def-

initions used to calculate the energy efficiency coeffi-

cients of water electrolysis cells working under near

ambient temperature conditions. Journal of power

sources, 447:227350.

Leblois, A., Reese, R., Labarre, D., Hamann, M., Richter,

A., Boraud, T., and Meissner, W. G. (2010). Deep

brain stimulation changes basal ganglia output nuclei

firing pattern in the dystonic hamster. Neurobiology of

disease, 38(2):288–298.

Lempka, S. F., Johnson, M. D., Miocinovic, S., Vitek, J. L.,

and McIntyre, C. C. (2010). Current-controlled deep

brain stimulation reduces in vivo voltage fluctuations

observed during voltage-controlled stimulation. Clin-

ical Neurophysiology, 121(12):2128–2133.

Lempka, S. F., Miocinovic, S., Johnson, M. D., Vitek, J. L.,

and McIntyre, C. C. (2009). In vivo impedance spec-

troscopy of deep brain stimulation electrodes. Journal

of neural engineering, 6(4):046001.

Liu, H., Wang, C., Zhang, F., and Jia, H. (2017). An im-

plantable device for neuropsychiatric rehabilitation by

chronic deep brain stimulation in freely moving rats.

NeuroReport, 28(3):128–133.

Merrill, D. R., Bikson, M., and Jefferys, J. G. (2005). Elec-

trical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of effi-

cacious and safe protocols. Journal of neuroscience

methods, 141(2):171–198.

Millard, R. E. and Shepherd, R. K. (2007). A fully im-

plantable stimulator for use in small laboratory ani-

mals. Journal of neuroscience methods, 166(2):168–

177.

Neumann, W.-J., Gilron, R., Little, S., and Tinkhauser, G.

(2023). Adaptive deep brain stimulation: From ex-

perimental evidence toward practical implementation.

Movement disorders, 38(6):937–948.

Nicksic, P. J., Donnelly, D. T., Verma, N., Setiz, A. J.,

Shoffstall, A. J., Ludwig, K. A., Dingle, A. M., and

Poore, S. O. (2022). Electrical stimulation of acute

fractures: A narrative review of stimulation protocols

and device specifications. Frontiers in Bioengineering

and Biotechnology, 10:879187.

Paap, M., Perl, S., L

¨

uttig, A., Plocksties, F., Niemann, C.,

Timmermann, D., Bahls, C., van Rienen, U., Franz,

D., Zwar, M., Rohde, M., K

¨

ohling, R., and Richter,

A. (2021). Deep brain stimulation by optimized stim-

ulators in a phenotypic model of dystonia: Effects

BIODEVICES 2025 - 18th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices

86

of different frequencies. Neurobiology of Disease,

147:105163.

Parastarfeizabadi, M. and Kouzani, A. Z. (2017). Advances

in closed-loop deep brain stimulation devices. Journal

of neuroengineering and rehabilitation, 14:1–20.

Parastarfeizabadi, M., Kouzani, A. Z., Gibson, I., and Tye,

S. J. (2016). A miniature closed-loop deep brain stim-

ulation device. In 2016 38th Annual International

Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and

Biology Society (EMBC), pages 1786–1789. IEEE.

Payonk, J. P., Bathel, H., Arbeiter, N., Kober, M., Fauser,

M., Storch, A., van Rienen, U., and Zimmermann,

J. (2025). Improving computational models of deep

brain stimulation through experimental calibration.

Journal of neuroscience methods, 414:110320.

Pinnell, R., Dempster, J., and Pratt, J. (2015). Miniature

wireless recording and stimulation system for rodent

behavioural testing. Journal of neural engineering,

12(6):066015.

Pinnell, R. C., de Vasconcelos, A. P., Cassel, J. C., and Hof-

mann, U. G. (2018). A miniaturized, programmable

deep-brain stimulator for group-housing and water

maze use. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12.

Plocksties, F., Kober, M., Niemann, C., Heller, J., Fauser,

M., N

¨

ussel, M., Uster, F., Franz, D., Zwar, M.,

L

¨

uttig, A., Kr

¨

oger, J., Harloff, J., Schulz, A., Richter,

A., K

¨

ohling, R., Timmermann, D., and Storch, A.

(2021a). The software defined implantable modular

platform (STELLA) for preclinical deep brain stim-

ulation research in rodents. Journal of Neural Engi-

neering, 18(5):056032.

Plocksties, F., L

¨

uttig, A., Niemann, C., Uster, F., Franz,

D., Kober, M., Koschay, M., Perl, S., Richter, A.,

K

¨

ohling, R., et al. (2022). Strategies on deep brain

stimulation devices for effective behavioral studies in

rodents. In 2022 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomed-

ical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), pages 376–

381. IEEE.

Plocksties, F., Shah, O. U., Uster, F., Ali, M., Koschay, M.,

Kober, M., Storch, A., and Timmermann, D. (2021b).

Energy-efficient modular RF interface for fully im-

plantable electrical devices in small rodents. In 2021

IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference

(BioCAS). IEEE.

Raben, H., K

¨

ammerer, P. W., and van Rienen, U. (2024).

Addressing model uncertainties in finite element sim-

ulation of electrically stimulated implants for critical-

size mandibular defects. IEEE Transactions on

Biomedical Engineering.

Reese, R., Charron, G., Nadjar, A., Aubert, I., Thiolat, M.-

L., Hamann, M., Richter, A., Bezard, E., and Meiss-

ner, W. G. (2009). High frequency stimulation of the

entopeduncular nucleus sets the cortico-basal ganglia

network to a new functional state in the dystonic ham-

ster. Neurobiology of disease, 35(3):399–405.

Ruiz, M. C. M., Guimar

˜

aes, R. P., and Mortari, M. R.

(2022). Parkinson’s disease rodent models: Are they

suitable for dbs research? Journal of Neuroscience

Methods, 380:109687.

Statz, M., Kober, M., Schleuter, F., Bathel, H., Plocksties,

F., Timmermann, D., van Rienen, U., Fauser, M., and

Storch, A. (2023a). Effects of deep brain stimulation

in the subthalamic nucleus (stn-dbs) on cellular plas-

ticity in catecholaminergic systems in a hemiparkin-

sonian rat model. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Trans-

lational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation,

16(1):313–314.

Statz, M., Schleuter, F., Weber, H., Kober, M., Plock-

sties, F., Timmermann, D., Storch, A., and Fauser, M.

(2023b). Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation

does not alter growth factor expression in a rat model

of stable dopaminergic deficiency. Neuroscience Let-

ters, 814:137459.

Ungerstedt, U. (1968). 6-hydroxy-dopamine induced de-

generation of central monoamine neurons. European

journal of pharmacology, 5(1):107–110.

van Dongen, M. N. and Serdijn, W. A. (2016). Does a

coupling capacitor enhance the charge balance during

neural stimulation? an empirical study. Medical &

biological engineering & computing, 54:93–101.

VARTA (2019). Technical Handbook CoinPower - Rechar-

gable Li-Ion Button Cells Generation A4. version 1.0.

Zhang, K. K., Matin, R., Gorodetsky, C., Ibrahim, G. M.,

and Gouveia, F. V. (2024). Systematic review of ro-

dent studies of deep brain stimulation for the treatment

of neurological, developmental and neuropsychiatric

disorders. Translational Psychiatry, 14(1):186.

STELLA+: Expanding the Research Potential for Long-Term Deep Brain Stimulation Studies in Freely-Moving Rodents

87