Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains:

A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

Laura Carmichael

1 a

, Steve Taylor

1 b

, Samuel M. Senior

1 c

, Mike Surridge

1 d

,

Gencer Erdogan

2 e

and Simeon Tverdal

2 f

1

IT Innovation Centre, University of Southampton, Southampton, U.K.

2

Sustainable Communication Technologies, SINTEF Digital, Oslo, Norway

Keywords:

Systematisation of Knowledge, Risk Management, Cybersecurity, Connected Medical Devices, In Vitro

Diagnostic Devices.

Abstract:

Shared terminology and understanding are vital for effective cybersecurity risk management for connected

medical and in vitro diagnostic device systems, given that such processes are collaborative and require cross-

domain expertise particularly, e.g., in the areas of patient safety, cyber-physical security, and privacy. However,

fostering effective, interdisciplinary risk communication can be challenging — especially where, e.g., different

terms are used with the same meaning, or the same risk management terms are interpreted differently across

domains. In this paper, we focus on the systematisation of security risk knowledge across different domains

related to the cybersecurity of connected medical and in vitro diagnostic device systems. This work relates

to knowledge base extensions for a specified cybersecurity risk assessment tool—Spyderisk—as part of the

NEMECYS project.

1 INTRODUCTION

A growing number of people depend on connected

medical and in vitro diagnostic devices (Quigley and

Ayihongbe, 2018) as part of wider “digital health

practices” (Busnatu et al., 2022)—e.g., to “deliver

medication, monitor body functions, or provide sup-

port to organs and tissues” (Food & Drug Ad-

ministration (FDA), 2019). Medical devices need

“connectivity” for various reasons—such as, to con-

nect “multiple sensors and actuators in body”, to

“[r]ecord data and transmit to practitioner”, to

“[m]onitor health status and treat (e.g., artificial pan-

creas, pacemaker)”, and to store “[p]ersonal data

for device operation (e.g., patient’s goal blood sugar

level)” (Badrouchi et al., 2020). For instance, some

connected medical devices contain sensors to “mea-

sure vital signals”, which are used to inform de-

cisions made by patients and clinicians that “result

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9391-1310

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9937-1762

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3428-9215

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1485-7024

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9407-5748

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1660-4127

in an action on the body” (Sliwa, 2018). Whereas

other connected medical devices contain “actuators”

that “act directly on the human body”—such as,

“pacemakers” and “insulin pumps” (Sliwa, 2018),

and a subset of these are implanted in the human

body (Tabasum et al., 2018).

While greater use of connected medical and in

vitro diagnostic devices can enhance individual care

and supported self-care practices, the increasing con-

nectivity of such devices also comes with greater

exposure to cyber threats that “can potentially lead

to increased risk of harm to patients” (Therapeu-

tic Goods Administration (TGA), 2022a). For in-

stance, cyber security threats could lead to “denial

of intended service or therapy”, “alteration of de-

vice function so that it can cause patient harm”

and “loss of privacy or alteration of personal health

data” (Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA),

2022b). In extreme cases, “the consequences of in-

adequate cybersecurity for connected medical devices

are perhaps some of the most dire, with the potential

for serious harm or even death” (Strunk, 2017).

Due to the ubiquity of ICT hardware, soft-

ware, and devices, cybersecurity concerns affect a

widespread and varied set of related domains. These

domains can be disciplines in their own right (e.g.,

Carmichael, L., Taylor, S., Senior, S. M., Surridge, M., Erdogan, G. and Tverdal, S.

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices.

DOI: 10.5220/0013306100003899

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Infor mation Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2025) - Volume 1, pages 337-348

ISBN: 978-989-758-735-1; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

337

privacy or safety), but they can also be sector-specific

(e.g., the medical sector, which is the focus of this pa-

per). Each domain has its own specialists and nomen-

clature, and there can be challenges in communica-

tion between the domains due to different naming

schemes. Further, it is often the case that cyberse-

curity is related to risk management, as this offers an

approach to assessing the likelihood and impact of the

consequences of threats, such as cyber-attacks or sys-

tem failures. Here, the threats may be in the cyberse-

curity domain, but their consequences and risks may

affect entities and actors who understand the termi-

nology of a related domain. There is thus a need to

organise (systematise) knowledge concerning cyber-

security and risk management and across multiple ar-

eas.

Shared terminology and understanding are there-

fore vital for effective cybersecurity risk management

for connected medical and in vitro diagnostic devices,

especially given that a risk governance framework

will involve multiple tools and approaches (Yaqoob

et al., 2019; Wu and Kusinitz, 2015). Yet, establishing

effective risk communication and fostering collabo-

ration between individuals and organisations can be

challenging in practice, as people from different or-

ganisations may use different cybersecurity risk man-

agement approaches and standards (Schmidt, 2023).

Even where the same standards are used there may be

different interpretations within an organisation (Wu

and Kusinitz, 2015). Further, in some cases the same

words can be used but with different meanings—for

instance, consider how the term “loss of availabil-

ity” can be interpreted differently in safety and secu-

rity contexts for connected medical devices (Piggin,

2017). It should also be emphasised that cybersecu-

rity risk management for connected medical devices

requires collaboration between people from multiple

domains with different levels of cybersecurity knowl-

edge. However, “[c]urrent definitions of cybersecu-

rity are not standardized and are often targeted to-

wards cybersecurity experts and academics” (Neil

et al., 2023).

In this paper, we focus on the systematisation of

security risk knowledge across different domains re-

lated to the cybersecurity of connected medical de-

vices as part of our work for the NEMECYS project

where we are contributing to the development of

“tools and procedures to help device manufacturers,

integrators and health care providers to ensure cyber

security by design for connected medical and diag-

nostic devices”

1

. As part of our research, we have

been developing an initial framework that aims to in-

tegrate the terminologies, risk processes, and eval-

1

https://nemecys.eu/overview/

uation methods from both cybersecurity and medi-

cal device domains (from specified sources as out-

lined in section 3 of this paper) into a unified ap-

proach. The objective being to facilitate collabora-

tion between e.g., cybersecurity professionals, device

manufacturers, integrators and health-care providers,

by fostering a shared understanding of risk concepts

and their implications for patient care related to spec-

ified cybersecurity risk assessment tools being devel-

oped as part of the NEMECYS project. Our work is

driven by four project use cases

2

.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2

describes the key steps taken to develop the initial

framework as part of the research method. Sec-

tion 3 identifies the specific standards, regulations,

and guidance that have been used to develop the

framework. Section 4, outlines an initial frame-

work to support the systematization of cross-domain

knowledge. Section 5 provides a brief summary of

related work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

Our research approach consists of the following four

steps to develop an initial framework supporting the

systematization of cross-domain knowledge in the

context of cybersecurity for connected medical and in

vitro diagnostic devices.

In Step 1, we integrated insights from litera-

ture and standards to support the validity of the

proposed framework (Section 3). This included

reviewing some existing frameworks for risk assess-

ment and management in both cybersecurity and med-

ical device domains. The review of standards served

as a backbone for the framework, ensuring that it

aligns with established protocols and can be readily

adopted by practitioners across fields.

In Step 2, which was carried out in parallel

with Step 1, we identified relevant definitions and

terminologies across the two domains: cybersecu-

rity risk management and medical device risk man-

agement (Section 3). This involved collecting con-

cepts and terminology from two international risk

management standards ISO 27005 (ISO/IEC, 2022)

and ISO 14971 (ISO, 2019), as well as aspects of the

EU regulatory framework concerning connected med-

ical and in vitro diagnostic devices. These sources

were carefully examined to capture terms that address

risk, harm, threats, and vulnerabilities. The goal was

to identify overlaps, discrepancies, and unique termi-

nologies within each domain, particularly where dif-

2

https://nemecys.eu/about-us/use-cases/

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

338

ferent terms are used for the same concept or the same

term is used with varying meanings [e.g., (Schmidt,

2023)]. This collection laid the foundation for a com-

prehensive comparative analysis between cybersecu-

rity and medical device contexts.

In Step 3, we systematically mapped risk con-

cepts to create a cross-domain understanding (Sec-

tion 4). By comparing frameworks like ISO 27005

(cybersecurity) (ISO/IEC, 2022) and ISO 14971

(medical devices) (ISO, 2019), key concepts such as

risk assessment, evaluation, and control were anal-

ysed in detail to understand their structure, process

flow, and any implicit assumptions in each domain.

This mapping aimed to bridge conceptual gaps and

provide a common basis for risk management in both

fields.

In Step 4, we developed an initial framework

to support the systematization of cross-domain

knowledge based on the mapping results (Sec-

tion 4). The initial framework integrates the ter-

minologies, risk processes, and evaluation methods

from both cybersecurity and medical device domains

into a unified approach. It aims to enable consis-

tent risk assessment by aligning the significant prop-

erties of assets (such as confidentiality, integrity, and

availability) with the unique requirements of con-

nected medical and in vitro diagnostic devices, like

patient safety and clinical efficacy. This cross-domain

framework is designed with the intention of facilitat-

ing collaboration between cybersecurity profession-

als, device manufacturers, integrators and health-care

providers—through fostering a shared understanding

of risk concepts and their implications for patient

care.

3 SCOPE

For the purposes of the NEMECYS project, we are

specifically focusing on two widely adopted interna-

tional risk management standards in the domains of

cybersecurity and medical device safety, which are:

• ISO 14971:2019 Medical Devices — Appli-

cation of Risk Management to Medical De-

vices (ISO, 2019). The ISO 14971 risk manage-

ment process applies “to all phases of the lifecy-

cle of a medical device” and the risk associated

with e.g., “biocompatibility, data and systems se-

curity, electricity, moving parts, radiation, and us-

ability”.

• ISO/IEC 27005:2022 Information Security,

Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection —

Guidance on Managing Information Security

Risks (ISO/IEC, 2022); part of the ISO/IEC

27000 family (ISO/IEC, 2018) concerning infor-

mation security management. For instance, ISO

27001 certification is commonly required in busi-

ness transactions.

The two processes for ISO 27005 and ISO 14971

are comparable, and follow similar structures—where

risk management comprises risk assessment, risk

evaluation and risk control (or treatment). For

further illustration, see e.g., guidance on cyberse-

curity provided by the Medical Device Coordina-

tion Group (MDCG, 2019), the MITRE Playbook

for Threat Modeling Medical Devices (MITRE and

MDIC, 2021) and British Standards Institution (BSI)

White Paper on Cybersecurity of Medical Devices

(Piggin, 2017) which all map a security process with

the ISO 14971 medical device safety risk process.

It is important to highlight that ISO 14971 ex-

plicitly mentions residual risk, which is the risk re-

maining after control measures have been employed

to treat the risks identified, but residual risk is also

highlighted in ISO 27005 as a determining factor to-

wards risk acceptance or iteration of the process in or-

der to identify more control measures to reduce resid-

ual risk.

It should be emphasised that “[r]isks related to

data and security are specifically mentioned in the

scope, to avoid any misunderstanding that a separate

process would be needed to manage security risks re-

lated to medical devices” (ISO, 2019, p. 18), thus

motivating the need to map cybersecurity risk assess-

ment and medical device risk assessment. A starting

point for this mapping is provided within ISO 14971,

which provides examples of where “[b]reaches of

data and system security can lead to harm, e.g.,

through loss of data, uncontrolled access to data, cor-

ruption or loss of diagnostic information, or corrup-

tion of software leading to malfunction of the medi-

cal device” (ISO, 2019, p. 19). Further, ISO 14971

is supported by guidance notes in the form of ISO

24971:2020 Medical devices — Guidance on the

application of ISO 14971 (ISO/TR, 2020). Annex

F of ISO 24971 guidance (ISO/TR, 2020, pp. 55-59)

specifically focuses on “risks related to security”. In

addition to providing a general overview, Annex F fo-

cuses on four key aspects: “terminology”, “relation

between ISO 14971 and security”, “characteristics of

security risk management”, and “prioritising confi-

dentiality, integrity, and availability”. While a brief

overview of security risk management terminology

is given by this informative guidance, more detailed

mapping between these domains is required. The next

section provides some examples of this mapping, in-

cluding concepts and definitions from both domains.

It is important to emphasise that the principal fo-

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

339

cus of the NEMECYS project is on the EU regula-

tory framework related to cybersecurity of connected

medical and in vitro diagnostic devices. In particular,

Annexes 1 of the Medical Device Regulation (EU,

2017a) and the In Vitro Diagnostic Devices Regula-

tion (EU, 2017b) contain cybersecurity requirements

for connected medical and in vitro diagnostic devices.

Further, the Medical Device Co-ordination Group

(MDCG) 2019-16 provides guidance on the cyber-

security for medical devices (MDCG, 2019). We

have therefore also used the MDR, IVDR and rele-

vant guidance issued by the MDCG as key sources

for identifying risk management concepts and defini-

tions.

4 INITIAL FRAMEWORK

In this section, we identify and describe some key

risk management concepts from various sources in

both cybersecurity and medical device domains—i.e.,

assets (section 4.1.1), significant properties (section

4.1.2), threats, hazards, events, incidents and haz-

ardous situations (section 4.1.3), consequences and

harm (section 4.1.4), and controls and corrective ac-

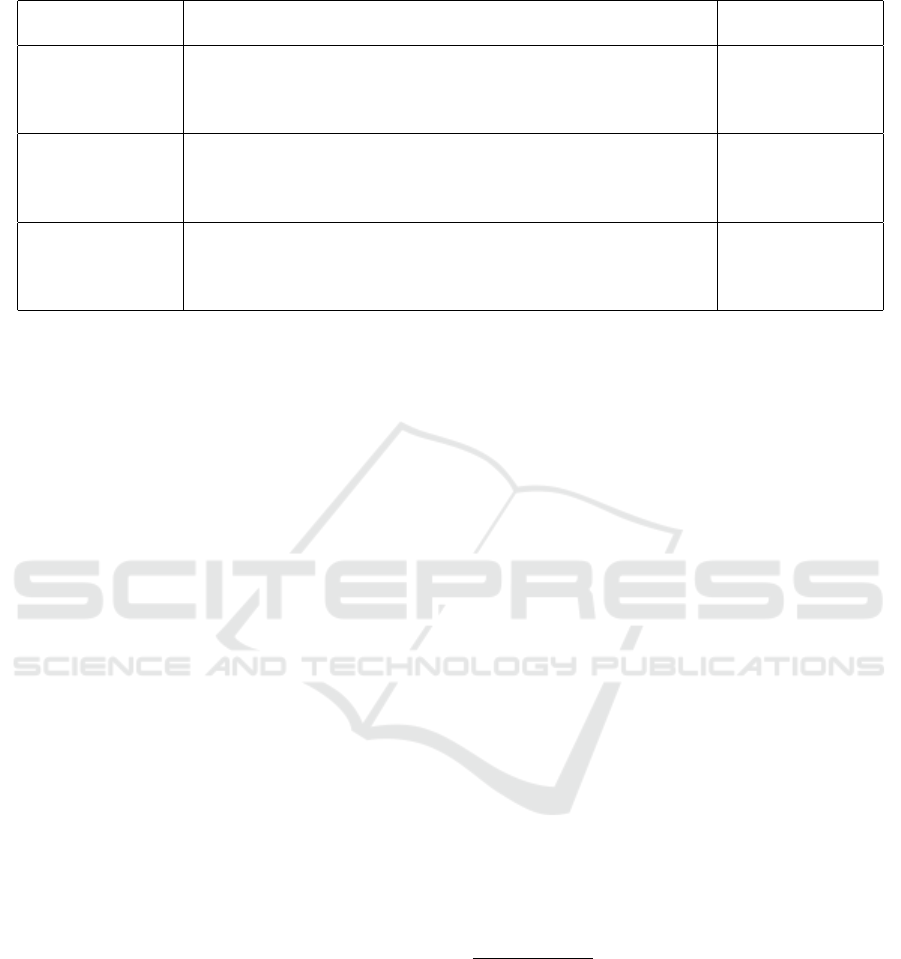

tions (section 4.1.5). Figure 1 provides a high-level

view of the relationships between these cross-domain

risk management concepts.

For purposes of illustration, we also discuss how

this cross-domain risk concepts mapping has been in-

terpreted for Spyderisk knowledge extensions in NE-

MECYS, providing examples of the different entity

types that need to be modelled. Spyderisk (Phillips

et al., 2024) is an existing knowledge-based ex-

pert system and automated risk simulator of cyber-

physical systems. Spyderisk follows ISO 27001 and

ISO 27005 (ISO/IEC, 2022), and is being extended

in NEMECYS in terms of automated risk assessment

related to the cybersecurity of connected medical and

in vitro diagnostic devices. Such knowledge exten-

sions require the systematisation of knowledge across

different domains.

4.1 Key Concepts

4.1.1 Assets

Brief Description. ISO 27005 takes an asset-based

approach to risk assessment. An asset refers to “any-

thing that has value to the organization and there-

fore requires protection” (ISO 27005). Connected

medical and in vitro diagnostic device systems con-

tain assets and the relationships between them. Asset

types for ICT derived from ISO 27005 include e.g.,

data, software processes, computer hardware, com-

puter networks. For modelling socio-technical sys-

tems involving the context in which these ICT com-

ponents operate, asset types also include e.g., people,

physical spaces and institutions, as these represent

actors who may cause threats, be affected by conse-

quences or describe the physical attributes of the en-

vironment.

Definitions. For asset see e.g., ISO 27005

(ISO/IEC, 2022), RFC 4949 (Shirey, 2007); and for

system see e.g., ISO 27000 [Information System]

(ISO/IEC, 2018), RFC 4949 (Shirey, 2007).

Spyderisk Knowledge Extensions. For con-

nected medical and in vitro diagnostic device sys-

tems, three main Asset types need extension, which

are: Human (people), Medical Device (which can be

either subclasses of Computer Hardware or Software)

and Data. Clearly, these map to Asset types described

in the cybersecurity domain, but specific subtypes are

required. Table 1 describes typical subtypes in each

of these Asset type categories. It should be noted that

there are interrelationships and dependencies between

these Asset types—e.g., different clinical workflows

may determine process chains where different medi-

cal devices, data and people interact to achieve a spec-

ified clinical objective.

4.1.2 Significant Properties

Brief Description. A significant property is viewed

as an attribute of an asset that is regarded as important

and needs to be upheld or preserved. In connected

medical and in vitro diagnostic device systems, ex-

amples of significant properties include: ensuring the

health, safety and wellbeing of patients and individ-

uals, realising expected clinical benefits

3

associated

with the use of such devices, and protecting the in-

tegrity, availability and confidentiality of data [e.g.,

(Ray, 2022b)].

Spyderisk Knowledge Extensions. As part of

NEMECYS, we have been exploring different types

of significant properties that are related to peo-

ple—e.g., clinical benefits related to effectiveness,

safety and timeliness of treatment, a person’s qual-

ity of life, and accuracy and timeliness of diagno-

sis with reference to e.g., MEDDEV 2.7/1 revision 4

(European Commission, 2016); MEDTECH 20 Ques-

3

The term “clinical benefit” is defined by Art 2(53) of

the MDR as “The positive impact of a device on the health

of an individual, expressed in terms of a meaningful, mea-

surable, patient-relevant clinical outcome(s), including out-

come(s) related to diagnosis, or a positive impact on patient

management or public health.” Of course, it should be noted

that “not all clinical benefits can be predicted” (Wilkinson

and van Boxtel, 2020).

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

340

Table 1: Examples of Asset Types.

Asset Type Asset Subtype Description

Human Patient Recipient of medical care.

Human User User of a medical device. May be Patient or other interested party

such as carer.

Human Clinician Provider of and decision maker about medical care.

Human Analytical Staff Analysts of Measurement Data and produce Test Results.

Human Medical Governance Responsible for policy and governance of hospitals.

Medical Device Sensor Device that observes Patient. Generates Measurements / Sensed

Data resulting from the observation.

Medical Device Actuator Device that administers energy (e.g., electricity for a pacemaker) or

substances (e.g., medication) to the Patient.

Medical Device Software (SaMD) Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). Software tools used in mon-

itoring / diagnosis / treatment of Patients.

Data Sensed Data / Measurements Observations resulting from Sensor monitoring / measuring specific

attributes of Patient.

Data Test Results Analysis results of Measurements. Often used as input to diagnostic

processes or to determine / adapt Treatment Plan.

Data Diagnosis Result Decision result of diagnostic process. Typically represents the iden-

tification of a disease.

Data Care Plan Documentation of process and resources for treatment of a Patient.

Typically uses diagnosis as input.

Data Actuator Configuration Control data for actuator containing parameters specifying e.g.,

dosage, timing, duration etc.

Data SaMD Configuration Any control data required for operation of SaMD

tionnaire (Les

´

en et al., 2017). Refer to Table 2 for

more information. Further, we have been examin-

ing significant properties related to data—e.g., “in-

tegrity”, “availability” and “confidentiality”, “au-

thenticity”, “possession or control” and “utility” as

presented by the “Parkerian Hexad” [see: (Andress,

2014); (Parker, 1998); (Piggin, 2017)], and “timeli-

ness”. Refer to Table 3 for more information.

We have also been looking at existing signifi-

cant properties related to connected medical and in

vitro diagnostic devices that pre-exist in the Spyderisk

Knowledge Base, known as the Spyderisk Network

Domain Model. As shown in Table 4, the signfi-

cant properties are grouped by the type of medical

device—i.e., Sensor, Software and Actuator. Sensors

are physical devices that measure quantities and gen-

erate data—and therefore incorporate the same sig-

nificant properties as data (e.g., confidentiality, in-

tegrity, availability, authenticity, timeliness). Sensors

may have software processes running within them, so

have significant properties associated with software

(e.g., availability, exploit trustworthiness, reliability

and timeliness). Sensors are also physical devices,

so have significant properties associated with devices

(e.g., control). Similarly, Software as a Medical De-

vice (SaMD) have the same set of significant proper-

ties associated with software processes. Actuators are

physical devices that are controlled by software pro-

cesses, so have the subsets of significant properties

associated with these subclasses.

4.1.3 Threats, Hazards, Events, Incidents and

Hazardous Situations

Brief Description. The term threat is used by ISO

27000 (ISO/IEC, 2018), which is defined as “poten-

tial cause of an unwanted incident, which can result

in harm to a system or organization”. Whereas, the

term hazard is utilised by ISO 14971 (ISO, 2019),

which means a “potential source of harm”. Threats

and hazards represent potential causes of unwanted

incidents, adverse events or hazardous situations that

lead to consequences. The risk management concepts

of events, incidents and hazardous situations there-

fore can be grouped together, as they denote the actual

manifestation of threats and hazards in the system un-

der evaluation.

Definitions. See e.g., ISO 14971 [Hazardous Sit-

uation]; ISO 27000 [Information Security Incident];

MDR Article 2(57) [Adverse Event]; MDR Article

2(58); [Serious Adverse Event]; MDR Article 2(64);

[Incident]; MDR Article 2(65) [Serious Incident].

Related Spyderisk knowledge extensions.

Threats and Hazards are modelled inside the Spy-

derisk Knowledge Base as specifications describing

the conditions under which the Incident or Event is

possible (determined by a configuration of Assets

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

341

Table 2: Examples of significant properties related to individuals in terms of clinical benefit.

Category of clini-

cal benefit

Sub-categories of clinical benefit and source Derived signifi-

cant properties

“positive impact on

clinical outcome”

(European Com-

mission, 2016)

“reduced probability of adverse outcomes, e.g. mortality, morbid-

ity”, “improvement of impaired body function” (European Commis-

sion, 2016)

Treatment Effec-

tiveness, Treatment

Safety, Treatment

Timeliness

“patient’s quality

of life” (European

Commission, 2016)

“simplifying care or improving the clinical management of patients”,

“improving body functions”, “providing relief from symptoms” (Eu-

ropean Commission, 2016). [Also see: MEDTECH 20 Question-

naire (Les

´

en et al., 2017).]

Patient Life Quality

”outcomes related

to diagnosis”

(European Com-

mission, 2016)

“allowing a correct diagnosis to be made”, “provide earlier diagnosis

of diseases or specifics of diseases”, “identify patients more likely to

respond to a given therapy” (European Commission, 2016)

Diagnosis Accu-

racy, Diagnosis

Timeliness

and relations that need to be present in the System

Model, known as a “matching pattern”) and the

resulting Consequence. When the user of the tool

builds a System Model, the Knowledge Base is

consulted to determine the Threats / Hazards that are

possible within the System Model, and those that are

determined possible become Incidents (or Events).

To illustrate the relationship between threats and haz-

ards, incidents, events and hazardous situations, and

consequences and harm, we consider the components

of a serious incident as defined in Article 2(65) of the

MDR. See Table 5 for a breakdown of this definition

to show these relationships.

4.1.4 Consequences and Harm

Brief Description—Consequences. The term con-

sequence is defined in ISO 27000 as “outcome of

an event affecting objectives”(ISO/IEC, 2018). Each

consequence has a risk level, which is determined by

two contributory factors. First, the likelihood of the

consequence is the chance of the consequence occur-

ring and is determined by the Spyderisk automated

risk assessment tool via examination of the likeli-

hoods of all incidents leading to a consequence. Sec-

ond, the impact (or severity) of the consequence is

how severe or intolerable a consequence is to the ob-

jectives of the key stakeholders in the system under

test. (Note: for Spyderisk, impact is usually set by

the analyst using the tool, as it is a reflection of the

preferences and tolerance of system stakeholders.)

Brief Description—Harm. When consequences

affect the preservation or maintenance of one or more

significant properties related to people—e.g. patients

and other users of medical devices—this can lead to

harm. The term harm is defined in ISO 14971 as “in-

jury or damage to the health of people, or damage to

property or the environment”. For the purposes of this

discussion, we will specifically consider harms to pa-

tients and other users, such harm may either be direct

or indirect.

Direct harm is actual injury to a person or dam-

age to a person’s health caused by the device (e.g.,

an actuator device administers an incorrect dosage

of medicine to a patient). However, in many cases

harm to people will be considered as indirect

4

—as

described by the MDCG (MDCG, 2024): “In most

cases, harm or a deterioration of health will be in-

direct if arising from an incident linked to a medi-

cal decision, actions taken, or lack thereof, which are

based on incorrect information, or results provided

by a device.” For example, MDCG Guidance classi-

fies different types of indirect harm resulting from in

vitro diagnostic device usage and information—i.e.

“a misdiagnosis”, “a delayed diagnosis”, “delayed

treatment”, “inappropriate treatment”, “absence of

treatment” and “transfusion of inappropriate materi-

als” (MDCG, 2024).

Definitions. See e.g., ISO 27000 (ISO/IEC,

2018) and ISO 27005 (ISO/IEC, 2022) [Conse-

quence, Likelihood, Risk]; ISO 14971 (ISO, 2019)

[Harm, Risk and Severity]; MDCG (MDCG, 2024)

[Indirect Harm].

Related Spyderisk Knowledge Extensions. As

part of NEMECYS, we have been focusing on mod-

4

As a further example, the UK MHRA states: “For

software as a medical device (SaMD), indirect harm is

the most probable outcome of adverse incidents and may

occur as a consequence of the medical decision, action

taken/not taken by healthcare professionals and/ or patients

and the public based on information or result(s) provided by

the SaMD” (Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory

Agency (MHRA), 2023). The MDCG 2022-2 also states:

“Due to their nature, in the majority of cases, deficiencies

of [in vitro diagnostic devices] IVDs do not directly lead to

physical injury or damage to the health of people. If any,

these devices may lead to indirect harm, rather than direct

harm” (MDCG, 2022).

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

342

Table 3: Examples of significant properties related to data.

Significant property Source

Availability means the data is accessible to authorised

parties when they need it.

See definition of Availability in: ISO/IEC 27000. Also

cited in: IEC Guide 120 (IEC, 2023) and Annex F to

ISO 24971 (ISO/TR, 2020).

Authenticity is a special subclass of integrity—the dif-

ference being that integrity is concerned with correct-

ness (freedom from errors and fit for purpose) whereas

authenticity is also concerned with freedom from delib-

erate alteration or forgery. The Parkerian Hexad defini-

tion also highlights attribution as an important aspect of

authenticity—i.e., whether the data’s author or creator

can be accurately identified.

From Parkerian Hexad: Andress (Andress, 2014);

Parker (Parker, 1998) (Also see (Piggin, 2017))

Confidentiality means the data is accessible only to au-

thorised parties (and no others).

See definition of confidentiality in ISO/IEC 24767-

1:2008, which is also cited in IEC Guide 120 (IEC,

2023) and Annex F to ISO 24971 (ISO/TR, 2020).

Also see definition of data confidentiality in RFC

4949 (Shirey, 2007)

Integrity determines if the data is free from corruption. ISO/IEC 27000:2018; and Annex F to ISO

24971 (ISO/TR, 2020)

Possession (or control) concerns access to copies of

data on physical media. This relates to the significant

property of availability—i.e., whether the only copy of

the data is lost. Possession also refers to multiple copies

of data that are present in different contexts. Each copy

must be guarded to ensure that control over its manage-

ment, which can affect its confidentiality (e.g., if one

copy is leaked) and integrity (e.g., if one copy or more

is corrupted).

From Parkerian Hexad: Andress (Andress, 2014);

Parker (Parker, 1998) (Also see (Piggin, 2017))

Timeliness means that the data is up to date, and is re-

lated to the significant property of availability.

Spyderisk Network Domain Model

Utility refers to whether the data is useful for its given

purposes. Data may be altered, which may impact its

usefulness. Typical examples of alteration that may af-

fect utility are encryption (e.g., the data is rendered use-

less if the recipient does not have the decryption key)

or redaction (e.g., removing certain parts of the data for

anonymisation purposes).

From Parkerian Hexad: Andress (Andress, 2014);

Parker (Parker, 1998) (Also see (Piggin, 2017))

elling types of indirect harms in Spyderisk concerning

use of connected medical and in vitro diagnostic de-

vices for diagnosis and treatment. For purposes of il-

lustration, Table 5 describes these indirect harms and

links them to the significant properties related to peo-

ple introduced above in Table 2.

4.1.5 Controls and Corrective Actions

Brief Description. The terms control and corrective

action are both used to describe measures or actions

taken that aim to modify risk by reducing the likeli-

hood of incidents resulting from a threat.

Definitions. See e.g., ISO 27000 [Con-

trol] (ISO/IEC, 2018); ISO 27005 [Vulnerability]

(ISO/IEC, 2022); MDR, Article 2(67), [Corrective

Action] (EU, 2017a); ISO 14971 [Risk Control] (ISO,

2019).

Examples. For instance, a “master set” of

twenty “technical cybersecurity controls” are out-

lined in (Ray, 2022a), which include: “Role-based

authorization and access control”, “Emergency ac-

cess”, “Restrict access” etc. For other examples, also

see: (Badrouchi et al., 2020) and (Sametinger et al.,

2015).

Related Spyderisk Knowledge Extensions. In

Spyderisk, Controls are applied at Assets and a Con-

trol Strategy is a collection of Controls applied to

Assets that are intended to work together. A Con-

trol Strategy also has an Effectiveness, which is the

strength of the combined Controls working on the As-

sets they are applied on to lower the likelihood of In-

cidents. The greater the effectiveness of the Control

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

343

Table 4: Examples of significant properties related to medical and in vitro diagnostic devices.

Asset Significant property Description

Sensor Authenticity The data (which may be embedded in an IoT device) is what it claims to be, i.e.

it is neither forged nor altered in a way designed to induce false behaviour in

other assets consuming the data.

Sensor Availability The asset is able to carry out its function within the system, including being

accessible by other assets that need to interact with it.

Sensor Confidentiality Signifies that data (which may be embedded in an IoT device) is only accessible

to authorised users.

Sensor Control Trustworthiness of the actor or process managing a host (including control over

access to the host) while it is connected to the system and fulfilling its system

role (i.e. in some context).

Sensor Exploit Trustworthiness Free of software vulnerabilities that are accessible to attackers.

Sensor Integrity The data (which may be embedded in an IoT device) is correct and fit for pur-

pose.

Sensor Reliability Means the asset will perform tasks correctly, with no functional errors, assum-

ing the asset is not supplied with corrupt or inaccurate information as input (in

the case of Human or Process assets).

Sensor Timeliness Represents a state in which a data asset is up to date, or a process or human has

up to date inputs.

Software Availability The asset is able to carry out its function within the system, including being

accessible by other assets that need to interact with it.

Software Exploit Trustworthiness Free of software vulnerabilities that are accessible to attackers.

Software Reliability Means the asset will perform tasks correctly, with no functional errors, assum-

ing the asset is not supplied with corrupt or inaccurate information as input (in

the case of Human or Process assets).

Software Timeliness Represents a state in which a data asset is up to date, or a process or human has

up to date inputs.

Actuator Availability The asset is able to carry out its function within the system, including being

accessible by other assets that need to interact with it.

Actuator Control Trustworthiness of the actor or process managing a host (including control over

access to the host) while it is connected to the system and fulfilling its system

role (i.e. in some context).

Actuator Exploit Trustworthiness Free of software vulnerabilities that are accessible to attackers.

Actuator Reliability Means the asset will perform tasks correctly, with no functional errors, assum-

ing the asset is not supplied with corrupt or inaccurate information as input (in

the case of Human or Process assets).

Strategy, the lower the Likelihood of the Incidents,

and the Control Strategy Effectiveness specifies an

upper limit on the Likelihood of the Incident it tar-

gets.

The Spyderisk Knowledge Base already has ex-

tensive controls and control strategies implemented

from the cybersecurity domain. These controls cover

the following areas: “Organisational Measures”,

“Physical Security”, “Service Security”, “Software

Security”, “Data Security”, “Network Security”,

“Client Security”, “Device Security”, “Resource

Management”, and “User Intervention” (Phillips

et al., 2024). For more information about these con-

trols refer to Phillips (2024). Many of these con-

trols are expected to address medical devices, as they

contain many of the components (hardware, soft-

ware, networks, spaces, etc.) already in the Spyderisk

Knowledge Base.

From the type of controls illustrated in the exam-

ples section above, it is clear that there is (unsurpris-

ingly) a strong crossover between the controls needed

for the cybersecurity of medical devices and those

needed for the cybersecurity of other application do-

mains. However, additional controls will be added as

necessary to accommodate specifics of medical and

in vitro diagnostic systems, which can work along-

side the existing cybersecurity controls. The controls

may be identified from multiple sources, such as the

above, other literature, consultation with experts or

in experiments following the use cases as part of the

NEMECYS project.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

344

Table 5: Components of ‘serious incident’ as defined by Article 2(65) of the MDR.

Legal definition for the term ‘serious incident’ is given by

Article 2(65) of the MDR as follows:

Spyderisk modelling approach

“Any incident” An instance of a Threat / Hazard occurring in the Sys-

tem under evaluation.

“That directly [. . . ] led, might have led or might lead to any of

the following”

Link from Incident to Direct Harm Consequences

“That [. . . ] indirectly led, might have led or might lead to any

of the following”

Link from Incident to Indirect Harm Consequences

“(a) the death of a patient, user or other person”, [/] (b) the

temporary or permanent serious deterioration of a patient’s,

user’s or other person’s state of health, [/] (c) a serious pub-

lic health threat”

Consequence / Harm

“(b) the temporary or permanent serious deterioration of a pa-

tient’s, user’s or other person’s state of health”

Consequence / Harm

“(c) a serious public health threat” [Not Yet Modelled]

Table 6: Indirect harm consequence types resulting from IVD usage (from MDCG 2023-3 (MDCG, 2024)).

Types of consequences that

may indirectly lead to harms

(MDCG 2023-3)

Modelling approach in Spyderisk Affected significant prop-

erties

“Misdiagnosis” Modelled as a Consequence for Humans to represent

incorrect diagnosis.

Diagnosis Accuracy

“Delayed Diagnosis” Modelled as a Consequence for Humans to represent a

diagnosis that is late.

Diagnosis Timeliness

“Delayed Treatment” Modelled as a Consequence for Humans to represent

late treatment.

Treatment Timeliness

“Inappropriate Treatment” Modelled as a Consequence for Humans to represent

incorrect treatment.

Treatment Effectiveness,

Treatment Safety

“Absence of Treatment” Modelled as a Consequence for Humans to represent

the lack of treatment.

Treatment Effectiveness,

Treatment Safety

“Transfusion of Inappropriate

Materials”

Not modelled explicitly — ‘transfusion of inappropriate

materials’ to be considered as a sub-case of ‘inappropri-

ate treatment’.

Treatment Effectiveness,

Treatment Safety

5 RELATED WORK

In terms of semantic interoperability for medical de-

vices, Sch

¨

utz et al. (Sch

¨

utz et al., 2021) have sought

to define a “core ontology for medical devices in Ger-

many”. More broadly, in terms of the “risk analysis

field”, the Society for Risk Analysis provide a Glos-

sary of terms which incorporates “different perspec-

tives and its systematic separation between overall

qualitative concepts and their measurements” (SRA,

2018). It should also be highlighted that in terms of

cybersecurity for medical devices, Ray (Ray, 2022b)

provides an introduction to “basic cybersecurity con-

cepts”. Further, the International Medical Device

Regulators Forum (IMDRF) has a working group fo-

cused on “adverse event terminology”—with one of

the aims being to “improve, harmonize and where

necessary expand the terminology and systems being

used to code information relating to medical device

adverse events” (International Medical Device Regu-

lators Forum (IMDRF), 2024).

As previously mentioned, guidance on cyberse-

curity provided by the Medical Device Coordina-

tion Group (MDCG, 2019), the MITRE Playbook

for Threat Modeling Medical Devices (MITRE and

MDIC, 2021) and British Standards Institution (BSI)

White Paper on Cybersecurity of Medical Devices

(Piggin, 2017) all map a security process with the

ISO 14971 medical device safety risk process. In re-

lation to comparing risk management concepts and

terms for information security, Schmidt (2023) re-

views well-known standards and frameworks, includ-

ing the ISO/IEC 27000 series, and examines some re-

lated work. A key concept diagram is also presented

mapping the relationships between them (Schmidt,

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

345

Figure 1: Overview of Some Key Risk Management Concepts.

2023). This comparison is centred on information se-

curity more generally, whereas our focus is on cross-

domain concept mapping for cybersecurity of con-

nected medical and in vitro diagnostic devices.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper presents an approach to systematizing

knowledge related to risk management across the do-

mains of cybersecurity and connected medical and in

vitro diagnostic devices. This work relates to knowl-

edge base extensions for a specified cybersecurity risk

assessment tool, Spyderisk, as part of the NEMECYS

project. Through a structured alignment of terminol-

ogy and risk concepts, based on the standards ISO

27005 (ISO/IEC, 2022) and ISO 14971 (ISO, 2019),

our approach aims to support a shared understanding

across diverse professional backgrounds.

The initial cross-domain framework proposed fur-

ther highlights the importance of integrated cyberse-

curity measures within connected medical and in vitro

diagnostic device systems, which are uniquely sus-

ceptible to threats that could compromise not only

device functionality but also patient safety, health,

and privacy. As future work, we intend to extend

the reported systematisation to encompass additional

healthcare-specific risks related to cybersecurity for

such systems.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

346

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been conducted as part of the NEME-

CYS project, which is co-funded by the European

Union (101094323), by UK Research and Innova-

tion (10065802, 10050933 and 10061304), and by the

Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and

Innovation.

Please note that this conference paper adapts and

extends part of a NEMECYS project deliverable re-

port: D2.1 Risk Benefit Schemes (initial).

REFERENCES

Andress, J. (2014). The basics of information security: un-

derstanding the fundamentals of InfoSec in theory and

practice. Syngress.

Badrouchi, F., Aymond, A., Haerinia, M., Badrouchi, S.,

Selvaraj, D. F., Tavakolian, K., Ranganathan, P., and

Eswaran, S. (2020). Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities in

Biomedical Devices: A Hierarchical Layered Frame-

work, pages 157–184. Springer International Publish-

ing, Cham.

Busnatu, S. S., Niculescu, A.-G., Bolocan, A., An-

dronic, O., Pantea Stoian, A. M., Scafa-Udris

,

te, A.,

St

˘

anescu, A. M. A., P

˘

aduraru, D. N., Nicolescu, M. I.,

Grumezescu, A. M., and Jinga, V. (2022). A review of

digital health and biotelemetry: Modern approaches

towards personalized medicine and remote health as-

sessment. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(10).

EU (2017a). Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the Euro-

pean Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017

on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC,

Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC)

No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives

90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC (Text with EEA rel-

evance.). http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/745/oj.

Accessed: 2024-11-13.

EU (2017b). Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the Euro-

pean Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017

on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repeal-

ing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision

2010/227/EU (Text with EEA relevance.). https:

//eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/746/oj. Accessed:

2024-11-13.

European Commission (2016). MEDDEV (MEDical

DEVices Documents) 2.7/1 revision 4 - Clini-

cal evaluation: a guide for manufacturers and

notified bodies under directives 93/42/EEC and

90/385/EEC. Guidelines on Medical Devices.

https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/17522/

attachments/1/translations/. Accessed: 2024-11-08.

Food & Drug Administration (FDA) (2019). Im-

plants and Prosthetics. https://www.fda.gov/

medical-devices/products-and-medical-procedures/

implants-and-prosthetics. Accessed: 2024-11-18.

IEC (2023). International Electrotechnical Commission,

IEC GUIDE 120:2023 - Security aspects - Guidelines

for their inclusion in publications.

International Medical Device Regulators Forum

(IMDRF) (2024). Adverse Event Terminol-

ogy. https://www.imdrf.org/working-groups/

adverse-event-terminology. Accessed: 2024-11-

20.

ISO (2019). International organization for standardization,

ISO 14971:2019 - medical devices — application of

risk management to medical devices.

ISO/IEC (2018). International organization for standardiza-

tion, ISO/IEC 27000:2018 - information technology

— security techniques — information security man-

agement systems — overview and vocabulary. https:

//www.iso.org/standard/73906.html.

ISO/IEC (2022). International organization for standard-

ization, ISO/IEC 27005:2022 - information security,

cybersecurity and privacy protection — guidance on

managing information security risks.

ISO/TR (2020). International organization for standardiza-

tion, ISO/TR 24971:2020 - medical devices — guid-

ance on the application of iso 14971.

Les

´

en, E., Bj

¨

orholt, I., Ingelg

˚

ard, A., and Olson, F. J.

(2017). Exploration and preferential ranking of pa-

tient benefits of medical devices: A new and generic

instrument for health economic assessments. Inter-

national Journal of Technology Assessment in Health

Care, 33(4):463–471.

MDCG (2019). MDCG 2019-16 rev.1 - guidance on cyber-

security for medical devices. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

MDCG (2022). MDCG 2022-2 Guidance on general princi-

ples of clinical evidence for In Vitro Diagnostic med-

ical devices (IVDs). Accessed: 2024-11-18.

MDCG (2024). MDCG 2023-3 rev. 1 - questions and an-

swers on vigilance terms and concepts as outlined

in the regulation (eu) 2017/745 and regulation (eu)

2017/746. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

(MHRA) (2023). Guidance for manufacturers on

reporting adverse incidents involving Software as a

Medical Device under the vigilance system. Ac-

cessed: 2024-11-18.

MITRE and MDIC (2021). Playbook for

Threat Modeling Medical Devices. https:

//www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/

Playbook-for-Threat-Modeling-Medical-Devices.

pdf. Accessed: 2024-11-08.

Neil, L., Haney, J. M., Buchanan, K., and Healy, C. (2023).

Analyzing cybersecurity definitions for non-experts.

In Furnell, S. and Clarke, N., editors, Human Aspects

of Information Security and Assurance, pages 391–

404, Cham. Springer Nature Switzerland.

Parker, D. B. (1998). Fighting computer crime: A new

framework for protecting information. John Wiley &

Sons, Inc.

Phillips, S. C., Taylor, S., Boniface, M., Modafferi, S., and

Surridge, M. (2024). Automated knowledge-based cy-

bersecurity risk assessment of cyber-physical systems.

IEEE Access, 12:82482–82505.

Systematisation of Security Risk Knowledge Across Different Domains: A Case Study of Security Implications of Medical Devices

347

Piggin, R. (2017). Cybersecurity of medical devices. https:

//www.bsigroup.com/meddev/LocalFiles/en-US/

Whitepapers/bsi-md-whitepaper-cybersecurity.pdf.

Accessed: 2024-11-08.

Quigley, M. and Ayihongbe, S. (2018). Everyday cyborgs:

On integrated persons and integrated goods. Medical

Law Review, 26(2):276–308.

Ray, A. (2022a). Chapter seven - cybersecurity design en-

gineering. In Cybersecurity for Connected Medical

Devices, pages 217–262. Academic Press.

Ray, A. (2022b). Chapter two - basic cybersecurity con-

cepts. In Cybersecurity for Connected Medical De-

vices, pages 29–77. Academic Press.

Sametinger, J., Rozenblit, J., Lysecky, R., and Ott, P.

(2015). Security challenges for medical devices. Com-

mun. ACM, 58(4):74–82.

Schmidt, M. (2023). Information security risk manage-

ment terminology and key concepts. Risk manage-

ment, 25(1):2.

Sch

¨

utz, A. E., Fertig, T., and Weber, K. (2021). Defin-

ing a core ontology for medical devices in germany

to ensure semantic interoperability. In Modelling and

Development of Intelligent Systems, pages 394–410,

Cham. Springer International Publishing.

Shirey, R. (2007). RFC 4949: Internet security glossary,

version 2.

Sliwa, J. (2018). Chapter 7 - security, privacy, and ethi-

cal issues in smart sensor health and well-being ap-

plications. In Wister, M., Pancardo, P., Acosta, F.,

and Hern

´

andez, J. A., editors, Intelligent Data Sens-

ing and Processing for Health and Well-Being Appli-

cations, Intelligent Data-Centric Systems, pages 121–

140. Academic Press.

SRA (2018). Society for Risk Analysis Glossary.

https://www.sra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/

SRA-Glossary-FINAL.pdf. Accessed: 2024-11-20.

Strunk, E. (2017). Momentum builds for medical device cy-

bersecurity to level up. https://www.fdli.org/2017/07/

momentum-builds-medical-device-cybersecurity-level/.

Accessed: 2024-11-13.

Tabasum, A., Safi, Z., AlKhater, W., and Shikfa, A. (2018).

Cybersecurity issues in implanted medical devices. In

2018 International Conference on Computer and Ap-

plications (ICCA), pages 1–9.

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (2022a).

Medical device cyber security guidance for in-

dustry. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/

medical-device-cyber-security-guidance-industry.

pdf. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (2022b).

Medical device cyber security information for

users. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/

medical-device-cyber-security-information-users.

pdf. Accessed: 2024-11-13.

Wilkinson, B. and van Boxtel, R. (2020). The medical de-

vice regulation of the european union intensifies focus

on clinical benefits of devices. Ther Innov Regul Sci,

54:613–617.

Wu, F. and Kusinitz, A. (2015). Best practices in ap-

plying medical device risk management terminol-

ogy. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology,

49(s1):19–24.

Yaqoob, T., Abbas, H., and Atiquzzaman, M. (2019). Se-

curity vulnerabilities, attacks, countermeasures, and

regulations of networked medical devices—a re-

view. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials,

21(4):3723–3768.

ICISSP 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

348