Analysis of Gaze Behavior for Constructing Learning Support Systems of

Pass Behavior in First Person Perspective

Norifumi Watanabe

1

and Kota Itoda

2

1

Graduate School of Data Science, Research Center for Liberal Education, Asia AI Institute, Musashino University,

3-3-3 Ariake, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan

2

Faculty of Data Science, Research Center for Liberal Education, Asia AI Institute, Musashino University,

3-3-3 Ariake, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

First Person Perspective, Gaze Behaviors, Cooperative Pattern, Learning Support System.

Abstract:

This study explores dynamic and adaptable human cooperative behavior in team sports such as soccer or

handball, emphasizing the sharing of intentions and actions among players. A key factor in this context is the

gaze direction of players, which is crucial for assessing situations and inferring teammates’ and opponents’

intentions, ultimately guiding practical actions. Recent advances in virtual reality (VR) technology have en-

abled detailed analysis of such behaviors and decision-making processes, facilitating experimental learning

scenarios in cooperative settings. In this research, we investigate human gaze behavior in soccer from a first-

person perspective, using head-mounted displays (HMDs) and virtual environments to develop supportive

learning systems. Through experiments in which subjects experience offensive scenarios from a real player’s

viewpoint within a VR environment, we analyze how their gaze behavior changes during different phases of

passing and attacking in the game.

1 INTRODUCTION

In our daily lives, we often deduce others’ intentions

from their actions and develop behavioral strategies

based on these interpretations. However, in collective

behaviors where multiple individuals must be evalu-

ated—such as in goal-oriented ball games like soccer

or handball—the complexity of the decision-making

process increases. One must discern which individu-

als to focus on and engage in a cascading estimation

of intentions, where understanding one person’s in-

tention leads to estimating another’s.

In games like soccer or handball, players choose

multiple potential teammates to whom they can pass

the ball, estimating each teammate’s intention to se-

lect the optimal passing option. By also evaluating the

positions and actions of opponents around potential

passing targets, players attempt to infer the most suc-

cessful passing choice. The ability to perform real-

time intention estimation and decision-making, under

strong temporal and spatial constraints, underscores

the necessity of inferring intentions within the group.

In addition to the importance of real-time inten-

tion estimation, the transfer of expert-level skills and

decision-making processes to novices is a critical as-

pect of sports training. Virtual reality (VR) offers a

promising platform for this expert–novice paradigm,

allowing less experienced players to observe and em-

ulate the gaze behavior and situational awareness of

professional athletes. By providing novices with im-

mersive, first-person perspectives of expert perfor-

mance, VR-based training can help bridge the gap

between theory and practice, enabling them to inter-

nalize the visual search patterns, tactical understand-

ing, and rapid decision-making that characterize ex-

pert players.

This study focuses on pass behavior, arguably the

most fundamental and important cooperative action in

ball games. We analyzed the gaze behavior of players

and conducted experiments in a virtual environment.

We developed specialized software to capture and an-

alyze the gaze of individual players using both track-

ing data and professional soccer video data. In the

experiment, we provided a first-person perspective of

professional soccer players as training data and recon-

structed their cooperative passing behavior in a virtual

environment. By repeatedly presenting specific sce-

narios through an HMD, we captured the ball holder’s

and receiver’s selection behavior during passes. We

then analyzed and evaluated changes in gaze behav-

1192

Watanabe, N. and Itoda, K.

Analysis of Gaze Behavior for Constructing Learning Support Systems of Pass Behavior in First Person Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0013306600003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 3, pages 1192-1198

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

ior before and after these passing actions. Based on

these findings, we discuss whether providing subjects

with a first-person perspective helps them shift gaze

behavior by inferring the intentions of the passer and

the receiver. We also consider the construction of a

learning support system.

2 STUDY ON HUMAN BEHAVIOR

ANALYSIS USING VIRTUAL

ENVIRONMENTS

With recent advances in information technology, it

has become possible to obtain tracking data that

record positional trajectories, gaze data, and biomet-

ric data such as heart rate or blood glucose levels from

various players, thus broadening the scope of data

analysis. Studies on recognizing group behavior us-

ing trajectory data have been conducted. These stud-

ies include coupling models of the Hidden Markov

Model (HMM) and hierarchical methods to model dy-

namic structures, thereby mining group behavior from

trajectory patterns (Blunsden et al., 2006)(Hervieu

et al., 2009)(Swears et al., 2014). While these stud-

ies share similarities with our research, our motiva-

tion differs. We aim not to predict group behavior but

rather to extract relationships among players and use

that information to interpret individual-level decision-

making.

In research on cooperative behavior in natural en-

vironments, analyzing the decision-making process

between trials is essential. This often requires repli-

cating the actions of both trained and untrained play-

ers. However, obtaining consistent behavioral sce-

narios in a real game environment can be challeng-

ing due to changing participants and varying weather

conditions. Large-scale equipment such as near-

360-degree curved displays or stadium environments

would be needed to faithfully recreate such scenarios

(Lee et al., 2010) and capture gaze behavior, but these

approaches have issues of low reproducibility or in-

sufficient realism.

To address these challenges regarding repro-

ducibility and human intent estimation, head-

mounted displays (HMDs) capable of presenting

field-of-view virtual environments from a first-person

perspective have recently become more accessible

and are widely used in cognitive training (Bideau

et al., 2010)(Miles et al., 2012). These devices have

been employed for athlete training, demonstrating

their effectiveness. Consequently, using virtual envi-

ronments in group behavior experiments and analyses

has become increasingly common.

In this study, we also employ a virtual environ-

ment to present group behavior from a first-person

perspective, facilitating repeated trials under consis-

tent conditions. This setup enables us to analyze

changes in behavior in an environment close to real

situations by providing a setting in which repeated ex-

periments are possible.

3 ANALYSIS OF GAZE

BEHAVIOR USING VIDEO AND

TRACKING DATA

This study analyzes videos presented in the virtual

environment to examine gaze behavior on a two-

dimensional plane. To analyze gaze behavior, we use

both video data and player tracking data. The data

set is from the Spain vs. Italy match in the 2013

FIFA Confederations Cup (de Football Association,

2015). The match video was recorded at 30 fps, and

the tracking data at 10 fps. The match video was cap-

tured from a fixed overhead camera at high resolution

(3840×2160), providing a comprehensive view of the

entire field. The tracking data include the coordinates

of all players on both teams and the position of the

ball on the field.

In this study, we map the gaze direction obtained

from the video data onto the tracking data to per-

form a thorough analysis. To achieve this, we devel-

oped a tool that synchronizes video data and track-

ing data. This tool enables us to view the game on

a two-dimensional plane generated from the track-

ing data, integrating gaze behavior data, manual in-

put, and video data in spite of differing frame rates.

Figure1 shows an overview of this analysis tool.

Figure 1: Overview of the Analysis Tool. An overview of

the analysis tool: [A][B] Video, [C] Plots of tracking data

and gaze data, [D] Folders and project files, [E] Debug con-

sole, [F] Main time management, and [G][H] Raw data re-

tention, with each module serving its respective role.

Analysis of Gaze Behavior for Constructing Learning Support Systems of Pass Behavior in First Person Perspective

1193

The figure indicates that after selecting a player

and then selecting another location, the tool calcu-

lates the angle relative to the initial player’s position.

This function allows us to acquire gaze direction on

the tracking data while reviewing the video, provid-

ing a seamless integration of gaze behavior analysis

with the video and tracking data.

4 EXPERIMENTAL

ENVIRONMENT USING HMD

AND VIRTUAL REALITY

We used head-mounted displays capable of presenting

a virtual environment—specifically, the Oculus Rift

DK2 from Oculus and the FOVE0 (Fov, ) from FOVE.

These HMDs have a field of view of approximately

100–110 degrees and are equipped with head track-

ing to seamlessly display the virtual environment ac-

cording to the user’s head movements. Additionally,

the FOVE0 is equipped with an eye-tracking system,

allowing us to analyze the subject’s gaze movement

while presenting the virtual environment.

In this study, we analyzed changes in gaze behav-

ior in two ways. First, we used the Oculus Rift’s

head tracking to analyze how changes in head direc-

tion shift the subject’s field of view. Second, we used

the FOVE0’s eye tracking to study how shifts in the

focus point affect behavior. The virtual environment

used in the experiment was built with Unity3D (Unity

Technologies). The virtual players were color-coded

in red and white according to their teams, and the pa-

rameters (e.g., field dimensions) were created based

on actual players and match regulations (Figure 2).

For simplicity, the players in the virtual environment

were represented by basic shapes (spheres and cylin-

ders).

Figure 2: Virtual Environment Used in the Experiment.

During the experiment, the position of players’

heads in the tracking data was aligned with the HMD,

allowing subjects to observe the gaze of one of the

real players. This method enables behavioral analy-

sis from a first-person perspective, making decisions

resemble real-life situations rather than an overhead

field view. The subject’s body in the virtual environ-

ment was rendered transparent so as not to obscure

surrounding objects. Figure 3 shows the virtual envi-

ronment and the experimental setup, and Table 1 lists

the primary parameters of the virtual environment.

Figure 3: Experimental Environment. Experimental envi-

ronment (the same screen displayed on the monitor in front

of a subject is presented on the HMD).

Table 1: Main Parameter Aetting of Virtual Environ-

ment[m].

Ball Diameter 0.2 Field Width 105.0

Player Height 1.7 Field Vertical 68.0

Player Width 0.4 Goal Width 7.3

Player Head Diameter 0.3 Goal Height 2.2

5 EXPERIMENT ON ACQUIRING

PASS BEHAVIOR USING GAZE

5.1 Scenes Used in the Experiment

Subjects were presented with a scene from the Spain

vs. Italy match in the 2013 FIFA Confederations

Cup (as described in Chapter 3), focusing on approx-

imately one minute of gaze behavior analysis dur-

ing the first half. This scene takes place mainly in

the midfield and involves passes among teammates,

culminating in a shot. The player whose viewpoint

was shared with the subjects was a midfielder (MF),

responsible for assessing the intentions of surround-

ing players and adjusting their actions accordingly.

The analysis focused on the subject’s gaze behavior

at each stage, from the beginning to the end of the

attack.

The Spanish team selected for this analysis is

renowned for its ball possession strategy and excep-

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

1194

tional passing skills. The players’ actions, believed

to be executed simultaneously based on shared inten-

tions, achieve precise passing (Ladyman, 2010).

5.2 Experimental Procedure

In the experiment, subjects repeatedly experienced

scenes created in the virtual environment to simulate

the pass-selection behavior of a midfielder. The vir-

tual players moved automatically based on tracking

data, and subjects observed this midfielder’s gaze be-

havior corresponding to the designated player in the

real match. Wearing the HMD, they could freely look

around and watch the surrounding situation in the vir-

tual environment. For safety, the experiment was per-

formed with subjects seated in a stable position.

The experiment was divided into three phases: the

“Pre-Phase,” the “Learning Phase,” and the “Post-

Phase.” In the Pre-Phase, subjects were allowed to

move their heads freely to observe the situations in

the corresponding scenes. In the Learning Phase, the

subject’s field of view was fixed, and the actual gaze

behavior of the player was shown. In the final Post-

Phase, subjects moved their heads based on the be-

havior they had observed during the Learning Phase.

Subjects were given instructions on what to focus on

during the scenes, guiding them on what to pay atten-

tion to.

Because multiple trials are needed to understand

gaze behavior while preventing VR sickness, each

phase was repeated three times. Afterward, a sim-

ple questionnaire was administered to gather informa-

tion about how the subjects experienced the ball game

and where they focused their gaze during the trials.

The subjects were university and graduate students

in their twenties, with no specialized or competitive-

level soccer experience. However, all had played

soccer to some extent in physical education classes,

providing them with basic familiarity with the sport.

Head direction was measured using the Oculus Rift

for four subjects, and eye tracking was performed us-

ing the FOVE0 for three subjects. To prevent VR sick-

ness, breaks of up to one minute were taken between

trials.

6 ANALYSIS OF GAZE

BEHAVIOR IN THE PRE- AND

POST-PHASES

6.1 Changes in Variance Across the

Overall and Different Stages of

Attack

In this scene, subjects performed four ball-passing in-

stances. To determine the extent of changes in sub-

jects’ gaze after the Learning Phase, we analyzed the

variance in gaze direction before and after this phase

across the entire scene. Since angular data, such as

gaze direction, have the unique property that an an-

gle of 360° is equivalent to 0°, the usual method of

mean and variance using sums of observations is not

directly applicable. Thus, we employ trigonometric

functions, as shown below:

(Rcos

¯

θ, Rsin

¯

θ) =

1

N

(

∑

cosθ,

∑

sinθ) (1)

V = 1 − R (2)

Here,

¯

θ represents the mean angle, V the vari-

ance, and N the number of data points. As the an-

gles become more aligned, the radial component R

approaches a unit vector, whereas lower alignment

causes R to approach 0. Therefore, as shown above,

the magnitude of the variance can range from 0 to 1.

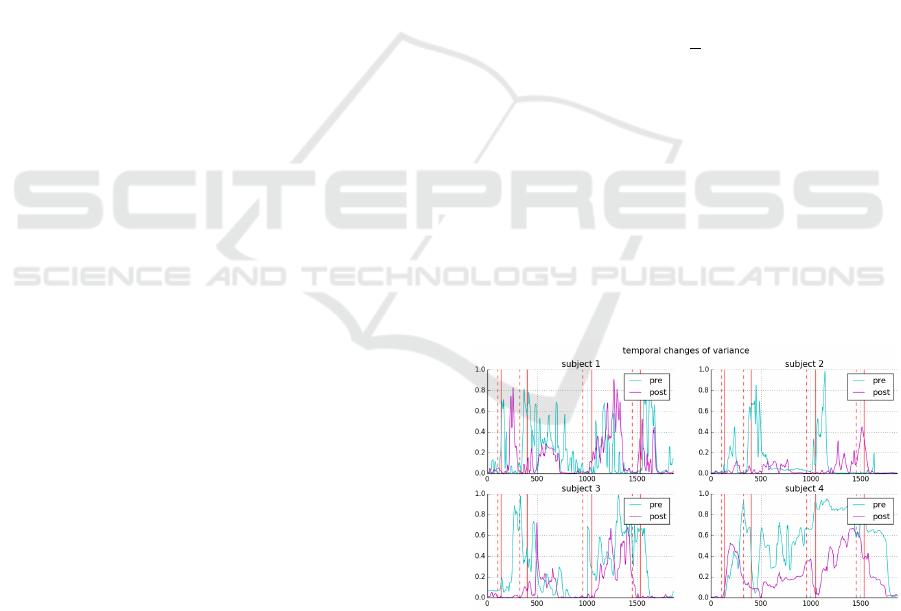

Figure 4 shows overall angular variance for each

of the three trials. Although some minor reversals are

visible, the overall variance generally decreases for

most subjects after undergoing the Learning Phase.

Figure 4: Changes in Variance of Subjects’ Gaze Behavior

in Pre- and Post-Phases.

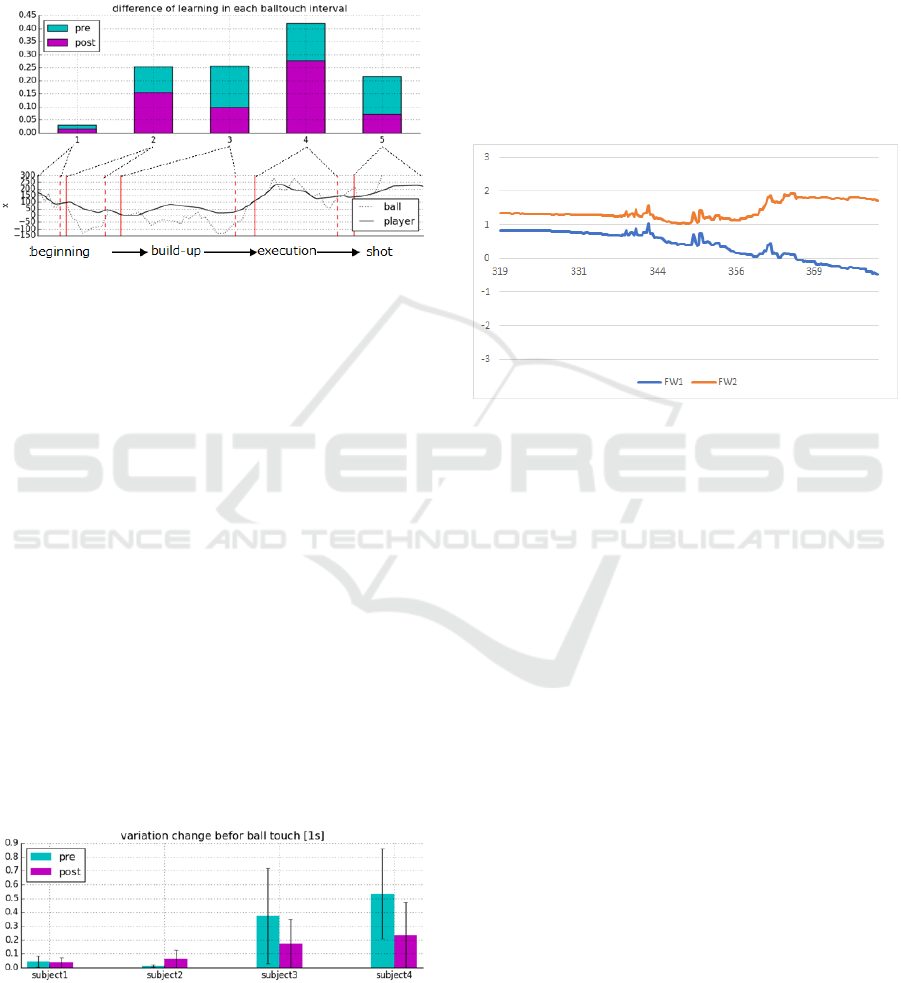

Additionally, to confirm how easily subjects learn

within a single scene, we segmented the scene by the

four instances of ball passing. We calculated the aver-

age gaze variance for all subjects (Figure 5). The up-

per part of Figure 5 shows the variance changes in the

Pre- and Post-Phases, and the lower part displays the

horizontal field positions of the ball and the players

Analysis of Gaze Behavior for Constructing Learning Support Systems of Pass Behavior in First Person Perspective

1195

corresponding to the subjects. The x-axis indicates

the field points toward the goal the subjects are attack-

ing. We categorized the stages of the attack into the

beginning, build-up, execution, and shot stages based

on the four ball-passing instances leading to the final

pass to the player who takes the shot.

Figure 5: Changes in Variance Reduction During the At-

tacking Stages (solid line represents players, dashed line

represents the ball’s position on the x-axis).

In scene 2, 3, and 5 of the Fig. 5, the variance val-

ues in the Pre-Phase were almost identical. Scene 3

and 5 showed a similar decrease in variance from the

pre- to the Post-Phase. However, in scene 4, which

represents the execution stage leading to the shot, the

decrease in variance in the Post-Phase was only com-

parable to the Pre-Phase variance of other scenes.

6.2 Changes Just Before Receiving the

Ball

To analyze gaze changes during pass behavior, Figure

6 shows the trial-averaged variance in the one second

just before receiving the ball. For subjects 1, 3, and

4, there are scenes between the third and fourth ball

touches, and for subjects 1 and 3, around 300 frames

after the second pass, where the variance values are

similarly high in both the Pre- and Post-Phases. How-

ever, in many cases, a decrease in variance is observed

in the Post-Phase.

Figure 6: Changes in Gaze Behavior Variance During the

One Second Before Receiving the Ball.

6.3 Analysis of the Players Actually

Observed

Furthermore, to investigate where the subjects were

focusing during coordination, we used the eye-

tracking function of the FOVE0 to determine which

players they were observing based on the variance

of angular data. Figure 7 shows the values extracted

from frames 319 to 379, during which the subject, af-

ter receiving the ball, passes it to another player. At

this moment, the subject is passing to a teammate for-

ward (FW).

Figure 7: Relative Angles (rad) of Other FW Players (1,2)

from Subject 1’s Gaze. Values are shown for frames 319-

379, where passes are exchanged with a teammate in the

presented video.

In the experiment, the positions of the players’

heads in the data set were aligned with the HMD,

allowing subjects to perceive the gaze of one of the

players. This setup enables behavioral analysis from

a first-person perspective, making decision-making

closer to real-life circumstances rather than a conven-

tional overhead view. By examining the relative an-

gles of the subject’s gaze towards two FW players,

it is observed that until around frame 340, FW1 and

FW2 are viewed at nearly the same angle. However,

from frame 340 onwards, the gaze shifts between the

two, and after frame 350, the relative angle towards

FW1 approaches zero, indicating a central gaze focus

on this player. This suggests that through the Learn-

ing Phase, subjects learn gaze behavior and actively

engage in exploratory actions during passing behav-

ior.

7 DISCUSSION

The reduction in time-series variance across the three

trials after the Learning Phase suggests that in the Pre-

Phase, subjects were mainly unaware of the surround-

ing situation and focused primarily on the ball. In

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

1196

contrast, the Learning Phase allowed them to grasp

the actual players’ gaze behavior, leading to a better

understanding of where to focus. Changes in gaze be-

havior just before receiving the ball, as seen in Figure

6, indicate that subjects learned the gaze pattern asso-

ciated with the player to whom they would pass the

ball.

In the attacking stage from midfield to the final

shot, as shown in Figure 5, the variance in gaze behav-

ior increased as the situation changed more rapidly

while challenging the opponent. Subjects lost track

of where to focus. After the fourth and final pass,

the variance decreased for all subjects, as they only

needed to watch their teammate take the shot. The in-

crease in variance immediately after the pass is likely

because the passes in this experiment were executed

automatically according to the actual players’ time-

series data, causing subjects to lose sight of the ball

briefly.

The post-experiment questionnaire revealed that

in the Pre-Phase, all four subjects mostly focused on

the ball or the player in possession. They occasion-

ally looked down to confirm the ball at their feet when

they had possession. This confirms that their search

for the ball, once an intended pass was executed, was

consistent with their level of awareness at that phase.

While no differences in variance due to angular

changes between trials were observed in the Pre- and

Post-Phases, the timing of gaze alignment increased,

indicating a narrower focal area. In the Pre-Phase,

subjects moved their heads significantly, leading to

large shifts in the focal area and increased variance.

In the Post-Phase, the focal area became more consis-

tent with the midfielder’s field of view, resulting in re-

duced variance. This suggests that information from

specific focus points increased, enabling better analy-

sis of other players’ actions and intent estimation.

When a teammate passed the ball to a subject, or

when the subject passed it to another player, the vari-

ance in each trial increased in the Post-Phase. In the

Pre-Phase, subjects did not focus visually and primar-

ily used peripheral vision to observe the entire spa-

tial situation. In the Post-Phase, they searched for the

teammate to whom they were passing and made de-

tailed gaze shifts to confirm the player’s actions, as

shown in Figure 7.

In this study, we primarily focused on central vi-

sion for our gaze analysis, which minimizes the im-

mediate impact of the relatively narrow field of view

(FOV) provided by current VR headsets. However,

peripheral vision is critical in real ball games, as it

allows players to perceive and respond to their sur-

roundings more comprehensively. Although center-

ing our analysis on central vision reduces the signifi-

cance of the FOV constraint in this particular context,

it remains true that standard VR devices cannot fully

replicate a player’s natural range of vision. For more

realistic simulations, especially when peripheral cues

play a larger role, employing wider-FOV headsets or

CAVE systems would be highly beneficial.

Regarding the gaze behavior analyzed in this

study, the number of subjects and the variety of scenes

were limited, primarily because each trial required a

considerable amount of time, making it difficult to re-

cruit a larger participant pool. Consequently, further

research is needed for a more comprehensive analy-

sis. In particular, to verify the learning effects on gaze

behavior, it will be important not only to present sub-

jects with new scenes similar to those analyzed in this

study but also to diversify the soccer scenarios, so as

to capture a broader range of offensive and defensive

contexts. By doing so, we can examine whether sub-

jects respond to novel situations in the same way as

they do to the learned ones. Moreover, because this

study only used visual information about the subject’s

gaze and certain players’ positions, it did not incor-

porate the gaze information of other players or addi-

tional cues commonly found in ball games. Future

work will address these limitations by increasing the

number of participants and expanding the variety of

experimental conditions, thereby enhancing the gen-

eralizability of our findings.

Nevertheless, the results of this analysis strongly

suggest differences in the ease of learning during vari-

ous stages of the attack. Future studies could compare

methods that offer more guidance to facilitate learn-

ing, for instance by providing additional information

or using cues to expedite the learning process.

8 CONCLUSION

In this study, we analyzed the gaze behavior of sub-

jects presented with a first-person perspective in a

virtual environment to build a learning support sys-

tem for cooperative pass behavior in soccer. By fo-

cusing on professional players’ gaze and decision-

making processes, we sought to establish a broader

framework in which expert skills can be transferred

to novices through immersive VR. Our experimen-

tal results showed that by sharing the gaze behavior

of professional soccer players, subjects were able to

limit their field of view to more relevant areas and

focus their gaze on specific players whose intentions

needed to be inferred. Within their constrained field

of view, subjects then attempted to infer the intentions

of multiple forwards (FWs).

These actions were effectively executed because

Analysis of Gaze Behavior for Constructing Learning Support Systems of Pass Behavior in First Person Perspective

1197

the subjects learned the gaze behavior associated with

pass actions presented during the Learning Phase.

Based on this learning, the subjects were able to per-

form exploratory gaze behaviors more actively. Al-

though this research used soccer as its primary case

study, the approach of presenting expert gaze and

decision-making in a virtual environment has the po-

tential to facilitate skill acquisition in a wide range of

domains.

Given the limited number of subjects and exper-

imental scenes, further research is needed to investi-

gate broader effects and to verify the consistency of

these findings in new, unfamiliar situations. In addi-

tion, incorporating other players’ gaze data or other

cues common in ball games may enrich the analy-

sis. As a next step, developing an agent-based VR

environment that integrates expert gaze and decision-

making models could broaden the applicability of our

framework and further facilitate skill transfer from ex-

perts to novices. By expanding both the variety of par-

ticipants and scenarios, as well as exploring applica-

tions beyond soccer, this framework can further illu-

minate how VR-based training supports skill transfer

from experts to novices.

REFERENCES

Fove 0. https://fove-inc.com/product/fove0/. Accessed:

2024-07-04.

Bideau, B., Kulpa, R., Vignais, N., Brault, S., Multon, F.,

and Craig, C. (2010). Using virtual reality to analyze

sports performance. Computer Graphics and Applica-

tions, IEEE, 30(2):14–21.

Blunsden, S., Fisher, R., and Andrade, E. (2006). Recog-

nition of coordinated multi agent activities, the indi-

vidual vs the group. In Proc. Workshop on Com-

puter Vision Based Analysis in Sport Environments

(CVBASE), pages 61–70.

de Football Association, F. I. (2015). Laws of the game.

FIFA.

Hervieu, A., Bouthemy, P., and Cadre, J.-P. L. (2009).

Trajectory-based handball video understanding. In

Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on

Image and Video Retrieval, page 43. ACM.

Ladyman, I. (2010). World cup 2010: Beat spain? it’s hard

enough to get the ball back, say defeated germany. ht

tp://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/worldcup2010/artic

le-1293239/WORLD-CUP-2010-Beat-Spain-Its-har

d-ball-say-Germany.html. Accessed: 2017-07-04.

Lee, W., Tsuzuki, T., Otake, M., and Saijo, O. (2010).

The effectiveness of training for attack in soccer from

the perspective of cognitive recognition during feed-

back of video analysis of matches. Football Science,

7(1):1–8.

Miles, H. C., Pop, S. R., Watt, S. J., Lawrence, G. P., and

John, N. W. (2012). A review of virtual environments

for training in ball sports. Computers & Graphics,

36(6):714–726.

Swears, E., Hoogs, A., Ji, Q., and Boyer, K. (2014). Com-

plex activity recognition using granger constrained

dbn (gcdbn) in sports and surveillance video. In Com-

puter Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2014

IEEE Conference on, pages 788–795. IEEE.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

1198