Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer

Yudai Yamamoto

1 a

, Viktor Koz

´

ak

2 b

and Ikuo Mizuuchi

3 c

1

Department of Food and Energy Systems Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Naka-cho 2-24-16,

Koganei-shi 184-0012, Tokyo-to, Japan

2

Czech Institute of Informatics, Robotics, and Cybernetics, Czech Technical University in Prague, Jugosl

´

avsk

´

ych Partyz

´

an

˚

u

1580/3, 160 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic

3

Department of Mechanical Systems Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Naka-cho 2-24-16,

Koganei-shi 184-0012, Tokyo-to, Japan

Keywords:

Medial Collateral Ligament, Lateral Collateral Ligament, Outside Pass, Strategies, Reinforcement Learning.

Abstract:

We study the leg motion for an outside pass in soccer, observing four different movement strategies. The aim

of this research is to validate the presence of these four strategies by training an agent with a higher reward

for kicking a faster ball. Additionally, we aim to explore the role of the collateral ligaments’ stiffness in the

outside pass. We built two leg models: (a) a two-degree-of-freedom leg model that applies torque around the

hip joint, and (b) a three-degree-freedom leg model that applies pitch-roll-yaw torque around the hip joint and

pitch torque around the knee joint. We trained a Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) agent using

these models and analyzed the torques around the hip and knee joints, as well as the ball velocity after the leg

loses contact with the ball. We observed three strategies similar to human behavior throughout agent learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are various types of passes in soccer, and each

pass is determined based on strategies. When focus-

ing on an outside pass without curve – where the ball

is kicked with the outside of the foot – we observe

four strategies: pulling the thigh backward diagonally,

bending the knee, stopping the thigh’s acceleration,

and stretching the knee suddenly. (Fig. 1). The body

motion can be studied using a mechanism embedded

in the human body called kinetic chain. The trans-

mission of the accumulated energy through kinetic

links and radiated energy at the time of ball throw

is demonstrated in (Senoo et al., 2008). The human

body has ability to store potential energy using its

elasticity (Chiras, 2018)(Ker et al., 1987)(Woo et al.,

1993)(Levin et al., 1927), We hypothesize that liga-

ment elasticity plays a role in energy accumulation

during the backward swing of the leg. For swing mo-

tion, using a robot by stopping the base link and ac-

celerating the end link is realized (Xu et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the use of elastic joint oscillation to

throw a faster ball by increasing the mechanical en-

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0004-1961-1992

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8405-269X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4657-2613

Figure 1: Four strategies of an outside pass in soccer are as

follows:(1-1) Pulling the thigh backward diagonally rotat-

ing the hip joint around the roll-pitch-yaw axes and the knee

joint around the roll-pitch axes, (1-2) Bending the knee ro-

tating knee joint around the pitch axis, (2-1) Stopping the

thigh’s acceleration rotating the hip joint around the roll

axis , and (2-2) Stretching the knee suddenly rotating the

knee joint around the pitch axis.

ergy has been demonstrated (Hondo and Mizuuchi,

2012). We assume that ligaments facilitate the ex-

change of kinetic and potential energy between the

thigh and shin, enabling the leg movement to effi-

ciently convert into the shin’s kinetic energy. Studies

on muscle tendon utilization during kicking (Cerrah

et al., 2011) , jumping (Fukasawa, 2000), and step-

Yamamoto, Y., Kozák, V. and Mizuuchi, I.

Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer.

DOI: 10.5220/0013306700003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 495-503

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

495

ping (Wiesinger et al., 2017)(Aeles and Vanwanseele,

2019) highlight the role of elastic elements. However,

research specifically focusing on ligament in sports

activities remains limited. In the case of an outside

pass, kicking the ball with the outside of the foot

may cause knee oscillation around the roll axis. The

goal of our research is to validate the presence of four

strategies in reinforcement learning agent with kick-

ing faster ball higher reward. Furthermore, we aim to

reveal the roles of collateral ligaments located on me-

dial and lateral side of the knee in an outside pass in

soccer.

2 THE STRATEGIES

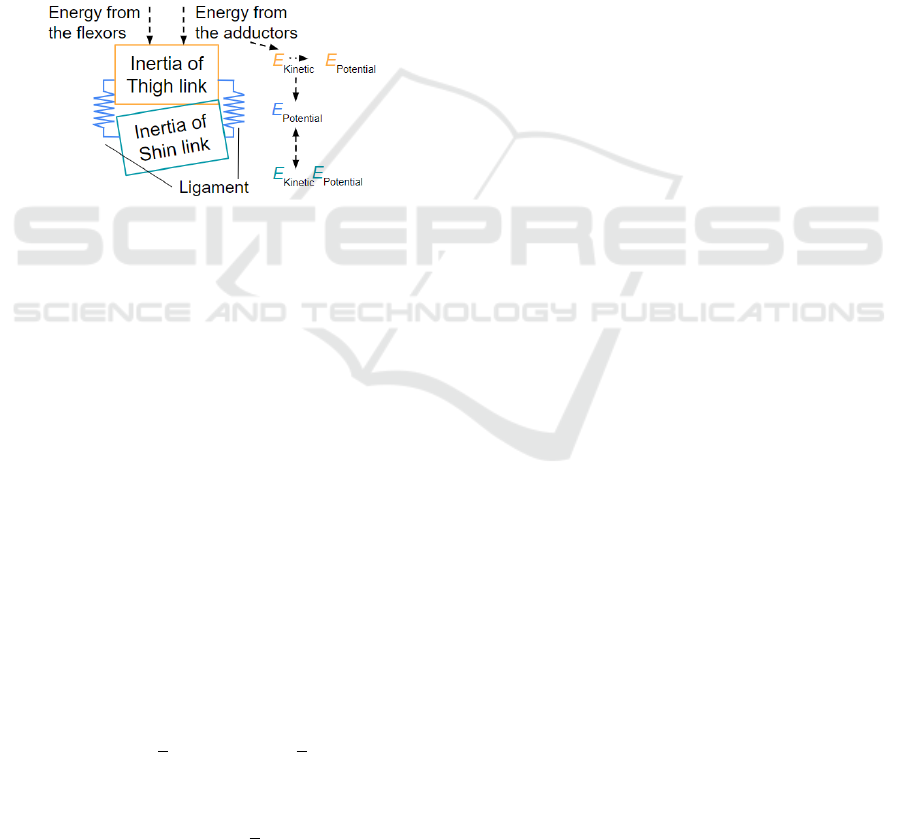

Figure 2: The four strategies collectively increase the ki-

netic energy of the shin, directing it towards the ball.

The rotational stiffness of the knee joint having two

collateral ligaments is non-linear. However for the

purpose of this research, the difference between non-

linear and linear joint stiffness is negligible. We mod-

eled the knee joint as two rigid links connected by a

torsional linear spring. The system’s equation of mo-

tion can be expressed as:

M

M

M(

(

(q

q

q)

)

)

¨

q

q

q + c

c

c(

(

(q

q

q,

,

,

˙

q

q

q)

)

) − τ

τ

τ

g

(

(

(q

q

q)

)

) = τ

τ

τ

p

(

(

(q

q

q,

,

,

˙

q

q

q)

)

) + u

u

u (1)

where q

q

q ∈ R

3

represents the generalized coordinates.

M

M

M(

(

(q

q

q)

)

) is the 3 × 3 inertia matrix, and c

c

c(

(

(q

q

q,

,

,

˙

q

q

q)

)

) ∈ R

3

is the Coriolis matrix. The terms τ

τ

τ

g

(

(

(q

q

q)

)

) and τ

τ

τ

p

(

(

(q

q

q,

,

,

˙

q

q

q)

)

)

are 3-dimensional vectors representing external joint

torques due to gravity, elasticity, and viscosity. Lastly,

u

u

u is the input torque vector. The total energy of

translational and rotational kinetic energy K(q

q

q,

˙

q

q

q), the

gravitational potential energy of the thigh and shin

U

Gravity

(q

q

q), and the ligament elastic potential energy

U

Elastic

(q

q

q) are expressed as follows:

K(q

q

q,

˙

q

q

q) =

1

2

v

v

v

T

COM

m

m

mv

v

v

COM

+

1

2

ω

ω

ω

T

I

I

Iω

ω

ω (2)

U

Gravity

(q

q

q) = −mg

g

gh

h

h (3)

U

Elastic

(q

q

q) =

1

2

kθ

θ

θ

2

(4)

where m is the mass, v

v

v

COM

is the center of mass

(COM) velocity, ω

ω

ω is the angular velocity, I

I

I is the

inertia tensor, h

h

h is the COM height, k is the knee

stiffness around roll axis, and θ

θ

θ is the knee roll an-

gle. Fig. 2 illustrates the energy flow between the

thigh and shin. Energy from the hip joint adductors

and knee joint flexors is transferred into the kinetic

and potential energy of the thigh, K

T high

and U

T high

(Pulling the thigh backward diagonally and bending

the knee). This increases the kinetic energy and ini-

tiates the kinetic chain. At the same time the hip

joint rotates around yaw axis to guide the kinetic en-

ergy toward the ball. Hip abduction and flexion are

small, with most of the energy goes to thigh’s kinetic

energy, K

T high

. This kinetic energy K

T high

then con-

verted into the potential energy of the ligaments and

muscle-tendon complex. By suddenly stopping the

motion of the hip joint along the roll, pitch, and yaw

axes, the kinetic energy is transferred to the lower

leg (Stopping the thigh’s acceleration). Consequently,

this action causes the knee joint to accelerate toward

the ball (Stretching the knee suddenly). After strik-

ing the ball, the leg does not swing through, reduc-

ing the thigh’s kinetic energy, K

T high

, and increasing

the shin’s kinetic energy, K

Shin

, and its potential en-

ergy due to gravity, U

Shin

. These four strategies col-

lectively work to increase the shin’s kinetic energy,

K

Shin

, and resulting in a faster ball. Taking the deriva-

tive of the kinetic energy in Eq. (2) with respect to

time t yields:

˙

K =

˙

v

v

v

T

COM

m

m

mv

v

v

COM

+

˙

ω

ω

ω

T

I

I

Iω

ω

ω (5)

The factors influencing the change in kinetic en-

ergy (K

Shin

) during swing motion have been studied

to explore methods for increasing the kinetic energy

of the end link (Asaoka and Mizuuchi, 2017). El-

ements such as angular acceleration, angular veloc-

ity, and the moment arm affect the energy transfer

rate within the leg. Studies on throwing (Tomohisa

et al., 1997)(Kozo and Takeo, 2006) and kicking mo-

tions (Kozo et al., 2007) have examined the energy

flow. Regardless of the scale of motion, even in out-

side pass, the acceleration and deceleration of the leg

ensure that kinetic energy flows from the thigh to the

shin.

3 METHODS

We determined the spring constant of the knee joint

around the roll axis based on the human parameters

(Table 1). Using reinforcement learning, we explic-

itly can decide a cost function for four strategies, such

as kicking a faster ball quickly. The reward function

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

496

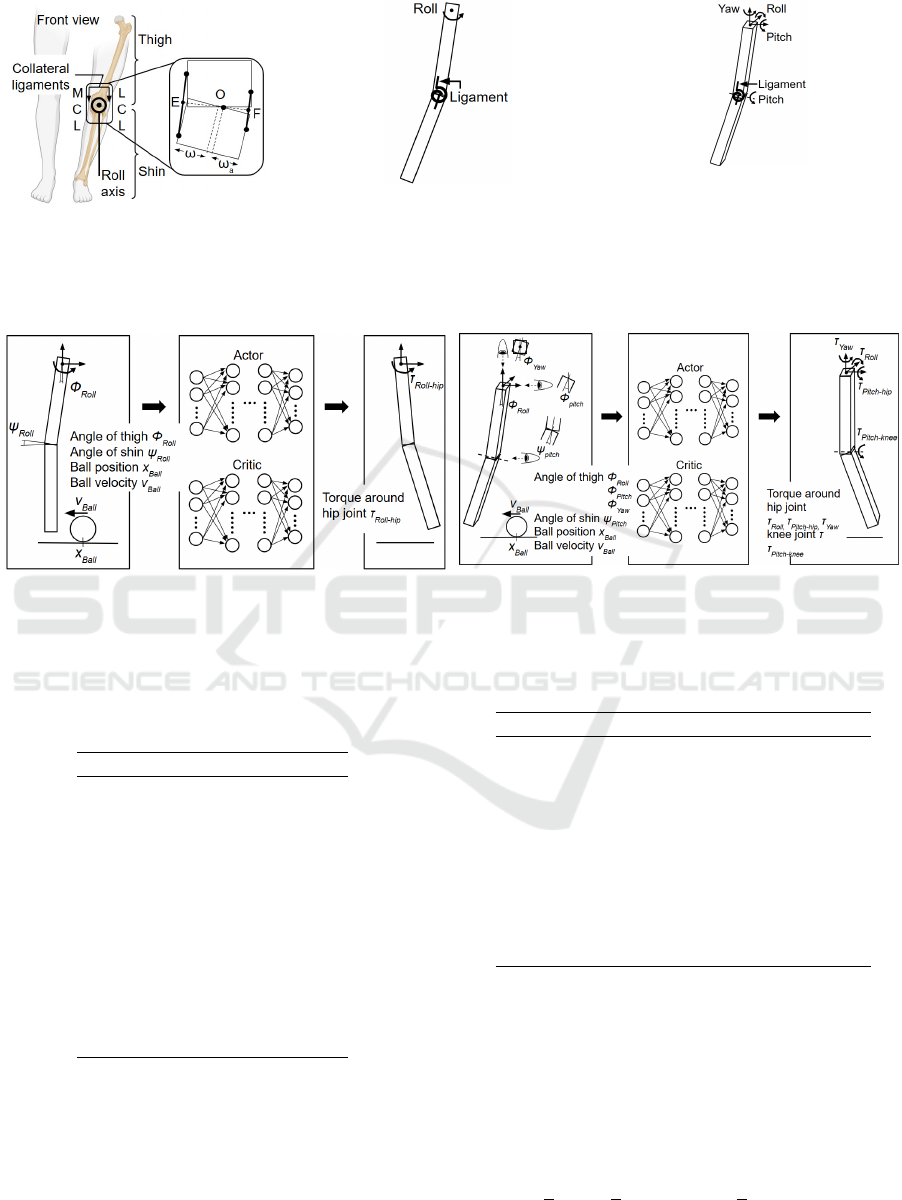

(A)

(B)

(a)Hip-Roll-Knee-Roll Leg Model

(C)

(b)Hip-RollPitchYaw-Knee-

RollPitch Leg Model

Figure 3: The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) are attached to the medial and lateral

sides of the knee joint. The stiffness of these ligaments is approximated as linear torsional stiffness for knee’s roll axis in both

(a) and (b).

(A) (B)

Figure 4: (A)The DDPG neural network model determines the torque input around the hip joint’s roll axis in knee model (a),

based on the angles of thigh and shin, the ball’s position, and its velocity. (B)The DDPG neural network model determines the

torque inputs around the hip and knee joints in knee model (b), based on the angles of the thigh and shin, the ball’s position,

and its velocity.

Table 1: Parameters of the leg and the ball (Ishii et al., 2009;

Herman, 2009; Ho-Jung and Dai-Soon, 2020; Christenson

and Casa, 2020; Nagurka et al., 2004).

Parameters Values

m

T high

7 kg

m

Shin

3.26 kg

m

Ball

0.43 kg

h

T high

0.4214 m

h

Shin

0.4231 m

w 0.0225 m

w

a

0.0147 m

l

MCL

68.99 × 10

−3

m

l

LCL

48.15 × 10

−3

m

k

MCL

71.97 × 10

3

N/m

k

LCL

69.70 × 10

3

N/m

k

Ball

10.88 × 10

3

N/m

was designed to ensure that the ball’s velocity after

impact is faster and that the range of motion of the

hip and knee joints remains within human limits (Ta-

ble 2). Under these conditions, we evaluated whether

the agent could gain a state-based action for the four

strategies.

Table 2: Human joint angle and torque limits.

Angle [deg] Torque [N · m]

Hip Joint

Flexion 132 105

Extension 15 158

Abduction 46 112

Adduction 23 76

Internal 38 84

External 46 67

Knee Joint

Flexion 154 126

Extension 0 229

3.1 Knee Joint Stiffness of Abduction

and Adduction

To simplify knee stiffness, we approximate the knee

as having a torsion spring instead of modeling it with

two ligaments. (Fig. 3(A)) Equating the potential en-

ergy of the ligaments to that of torsion spring gives

us

1

2

kθ

2

=

1

2

k

MCL

∆l

2

MCL

+

1

2

k

LCL

∆l

2

LCL

(6)

Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer

497

where k represents the torsion spring constant, and θ

is the small flexion angle around the roll axis. k

MCL

and k

LCL

are the stiffness values of the two ligaments,

while ∆l

MCL

and ∆l

LCL

represent the elongations from

natural lengths. For small angles θ, ∆l

MCL

≈ |OE|θ,

∆l

LCL

≈ |OF|θ , where |OE| and |OF| are the moment

arms illustrated in Fig. 3(A).

K = k

MCL

|OE|

2

+ k

LCL

|OF|

2

(7)

Assuming small values for θ, |OE| and |OF| can

be considered constant: |OE|

2

= 2w

2

(1 − w

a

)

2

+

(l

2

MCL

/2) and |OF| = 2w

2

w

2

a

+ (l

2

LCL

/2), where l

MCL

and l

LCL

are the natural lengths of each ligament.

Using this approximation, the knee joint stiffness is

about 137 Nm/rad.

3.2 Leg and Leg-Ball Contact Model

We used two types of leg models: (a) Hip-

Roll-Knee-Roll Leg Model (Fig. 3(B)) and (b)

Hip-PitchRollYaw-Knee-PitchRoll Leg Model (Fig.

3(C)). Both models consist of two rigid links. In leg

model (a), the hip and knee joints rotate around the

roll axis, Φ

Roll

and Ψ

Roll

, respectively (Fig. 4(A)).

In leg model (b), the hip joint moves around the pitch,

roll, and yaw axes, while the knee joint rotates around

the pitch and roll axes, Φ

ROll

, Φ

Pitch

, Φ

Yaw

, Ψ

Roll

, and

Ψ

Pitch

(Fig. 4(B)). When the knee joint flexes around

the pitch axis, the lengths of the anterior cruciate liga-

ment and posterior cruciate ligament change (Li et al.,

2004). However, in this study, we focus only on the

knee stiffness around the roll axis, which is set to 100

N/rad. The damping of both the hip and knee joints

is set to 0.1 Nm/deg/s (Herman, 2009). At around 0

degrees of shin flexion relative to the thigh, the rota-

tional point of the knee joint around the roll axis is

located about 32.6% of the distance from the lateral

to the medial epicondyle (Dhaher and Francis, 2006).

The Contact model between the leg and the ball is ex-

pressed as s(d, w) · (k · d), where s(d, w) is a function

that monotonically increases from 0 to 1 as the pene-

tration d is less than the transition region width w. We

set w to 10

−4

m and the ball stiffness k to 100 N/m.

3.3 Workflow of Reinforcement

Learning

We made a DDPG agent using the Simulink Re-

inforcement Learning Toolbox (MATLAB 2024a,

The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, United

States). We used DDPG, one of the actor-critic meth-

ods, because actor-critic methods can explore the con-

tinuous actions (Grondman et al., 2012). To further

explore the actions, we set the StandardDeviation to

1 and the StandardDeviationDecayRate to 0, increas-

ing the amount of noise in Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Ac-

tion Noise. Regarding the environment setup, the leg

initially starts in a straight position to the ground, with

no angular velocity, while the ball is situated at 0.55

m from the leg and has velocity to move horizontally

toward the leg. To let the ball hit to the leg, we applied

a pulse input of 134 force toward the ball for 3 ms us-

ing the External Force and Torque block in Simulink.

The time step for the simulation was set to 0.1 s.

3.3.1 Hip-Roll-Knee-Roll Leg Model

The DDPG agent (Lillicrap et al., 2019) outputs a

continuous action of torque around the hip joint in

the roll axis, τ

Roll−hip

, based on observations such as

the thigh angle Φ

Roll

, shin angle Ψ

Roll

, ball position

X

Ball

, and ball velocity V

Ball

(Fig. 4(A)). The reward

for action is set as follows:

R =

(

10V

Ball

−t −100 Φ

Roll

̸∈ (−23

◦

,46

◦

)

10V

Ball

−t Φ

Roll

∈ (−23

◦

,46

◦

)

(8)

where V

Ball

represents the current velocity of the ball

when it leaves the ball, and t is the current simula-

tion time. Each episode ends when the ball position

reaches a distance of 0.8250 m from the leg or when

the number of thigh swings reaches to 10 times. The

torque around the hip joint ranges between −76 N· m

and 112 N· m (Lanza et al., 2021) (Table 2). The op-

timization algorithms for optimizing the loss of both

the actor and critic were Adam (Adaptive movement

estimation).

3.3.2 Hip-RollPitchYaw-Knee-RollPitch Leg

Model

The DDPG agent outputs continuous actions of torque

around the hip joint in the pitch τ

Pitch−hip

, roll τ

Roll

,

yaw τ

Yaw

axes, as well as around the knee joint in the

pitch axis τ

Pitch−knee

based on observations such as the

thigh angle Φ

Pitch

Φ

Roll

Φ

Yaw

, the shin angle Ψ

Pitch

,

ball position X

Ball

, and ball velocity V

Ball

(Fig. 4(B)).

We assume that we do not change anything depend

on the knee ligament condition when policy is built.

Additionally, to enhance learning efficiency, we did

not employ the knee joint roll angle Ψ

Roll

for obser-

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

498

vations. The reward for the actions is set as follows:

R =

15V

Ball

−t − 200

Φ

Pitch

̸∈ (−132

◦

,15

◦

)

Φ

Roll

̸∈ (−46

◦

,23

◦

)

Φ

Yaw

̸∈ (−38

◦

,46

◦

)

Ψ

Yaw

̸∈ (0

◦

,154

◦

)

15V

Ball

−t

Φ

Pitch

∈ (−132

◦

,15

◦

)

Φ

Roll

∈ (−46

◦

,23

◦

)

Φ

Yaw

∈ (−38

◦

,46

◦

)

Ψ

Yaw

∈ (0

◦

,154

◦

)

(9)

where V

Ball

represents the current velocity of the ball

when it leaves the leg, and t is the current simula-

tion time. Each episode ends when the ball posi-

tion reaches a distance of 0.8250 m from the leg or

when the number of thigh swings reaches to 10 times.

The torque around the hip joint in the pitch, roll and

yaw axes ranges from −105 N· m to 158 N· m, from

−112 N· m to 76 N· m, and from −84 N· m to 67

N· m, respectively (Lanza et al., 2021)(Lindsay et al.,

1992)(Pontaga, 2004)(Dibrezzo et al., 1985).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

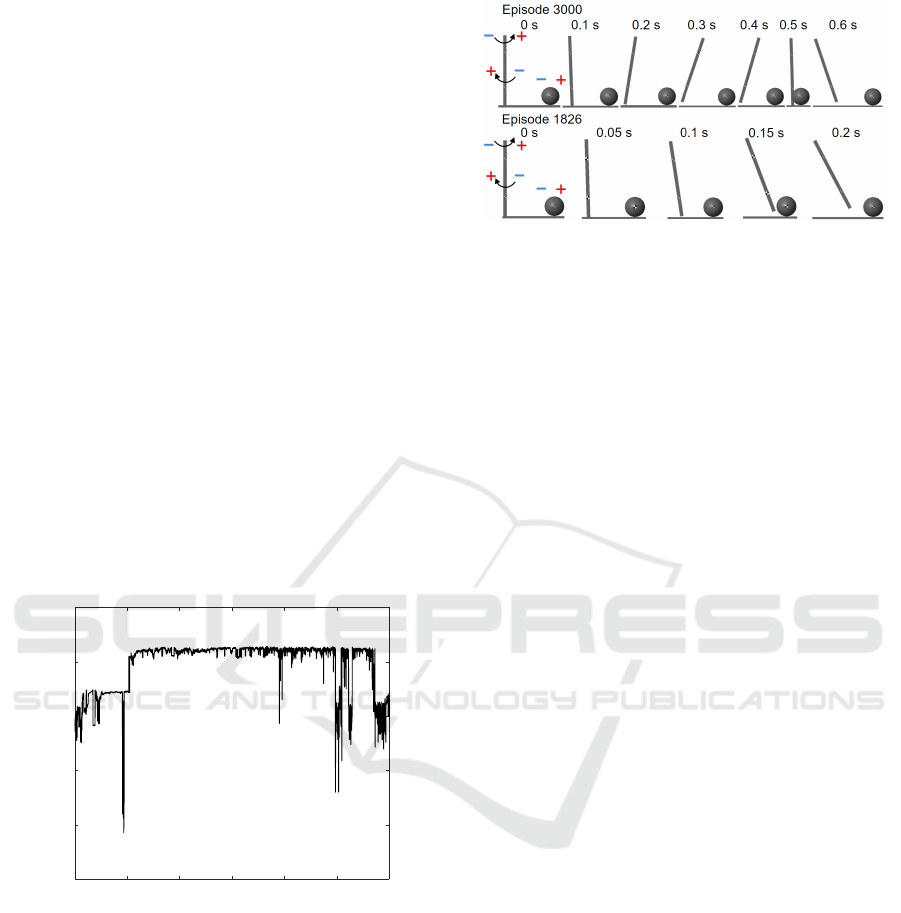

0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000

Number of Training Episodes

-150

-100

-50

0

50

100

Episode Reward Mean

Figure 5: Episode Reward Mean for (a) Hip-Roll-Knee-

Roll Leg Model.

4.1 Hip-Roll-Knee-Roll Leg Model

We trained the DDPG agent for 3000 episodes to en-

sure the reward had converged and the episode reward

mean converged around 500 episodes (Fig. 5). In

episode 3000, the agent applies a torque of 61.8 N · m

at 0 s, which reduces to −68.9 N ·m and then grad-

ually increases to 57.6 N ·m until the leg strikes the

ball at 0.49 s (Fig 7(C)). This torque sequence causes

the leg to move forward, then backward, and forward

again, which is pulling the thigh backward diagonally

Figure 6: Motion snapshots of model (a) at 3000 and 1826

episode.

(Fig. 6, Fig 7(A)). During this motion, the shin’s roll

angle oscillates due to ligament elasticity, which al-

lows the ligaments to hold potential energy until the

leg makes contact with the ball (Fig 7(B)). Pulling the

thigh backward diagonally causes this oscillation and

contributes to the onset of energy flow. After the leg

strikes the ball at 0.49 s, the hip torque around the

roll axis decreases, corresponding to the stopping the

thigh’s acceleration. This deceleration facilitates the

transfer of energy from the thigh to the shin. Addi-

tionally, it induces knee roll oscillation during con-

tact. The ball velocity reaches 6.13 m/s.

In 1826 episode, which achieved the highest

Episode Reward Mean, the agent applied a torque to

swing the leg to the ball with 110 N· m at 0.098 s.

This torque was reduced to 8.32 N· m at 0.18 s when

the leg contacts the ball (Fig. 7(F)). This reduction in

torque corresponds to stopping the thigh’s accelera-

tion (Fig 7(F)), enabling kinetic energy transfer from

the thigh to the shin and inducing oscillation of the

knee joint around roll axis (Fig 7(E)). Unlike 3000

episode, the hip joint angle increases monotonically,

and we did not observe the pulling the thigh back-

ward diagonally (Fig 7(D)). The ball’s velocity was

6.57 m/s when the leg lost contact.

4.2 Hip-RollPitchYaw-Knee-RollPitch

Leg Model

We tuned the hyperparameters (actor and critic learn-

ing rates and discount factor) using Bayesian opti-

mization in the Simulation Manager of MATLAB. We

set the actor learning rate, critic learning rate, and dis-

count factor in the range between 10

−3

and 1. We

set the metrics EpisodeReward to maximize it with a

maximum number of 30 trials. We tested two sets of

hyperparameters (Table 3). In the first set, we did not

observe the reward convergence while observe it in

the second set (Fig. 9). For the second set of tuned hy-

perparameters, We tuned the hyperparameters insert-

ing a Minibatch normalization layer between the fully

Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer

499

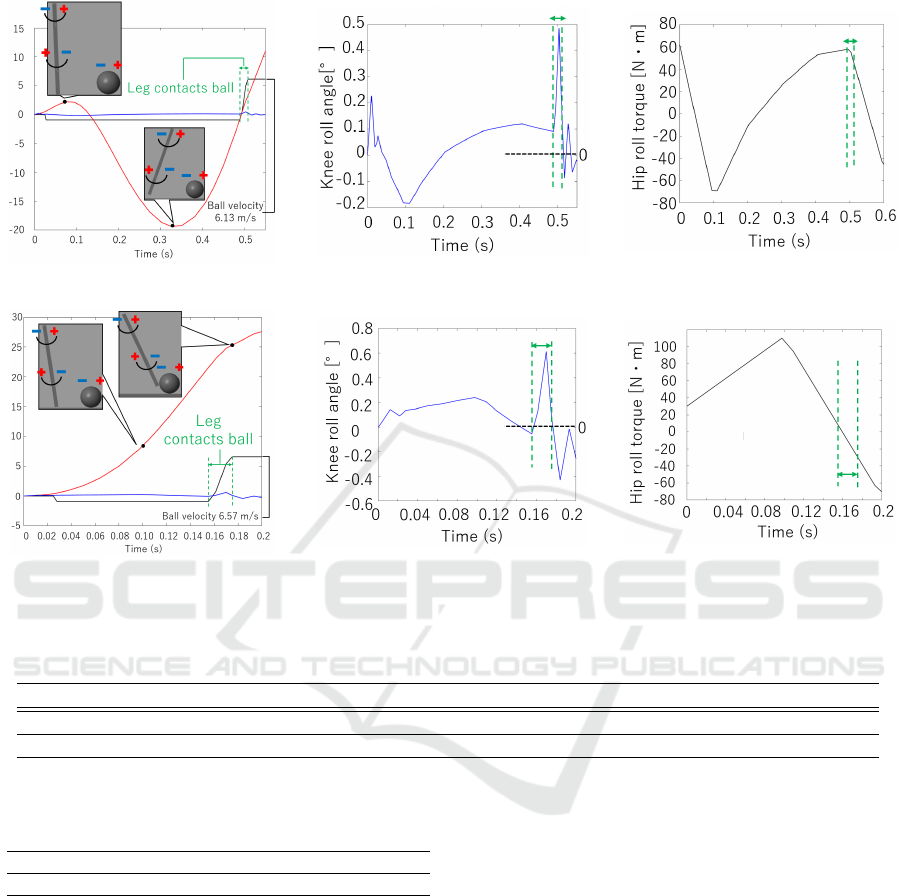

(A)

(B)

(C)

(D)

(E)

(F)

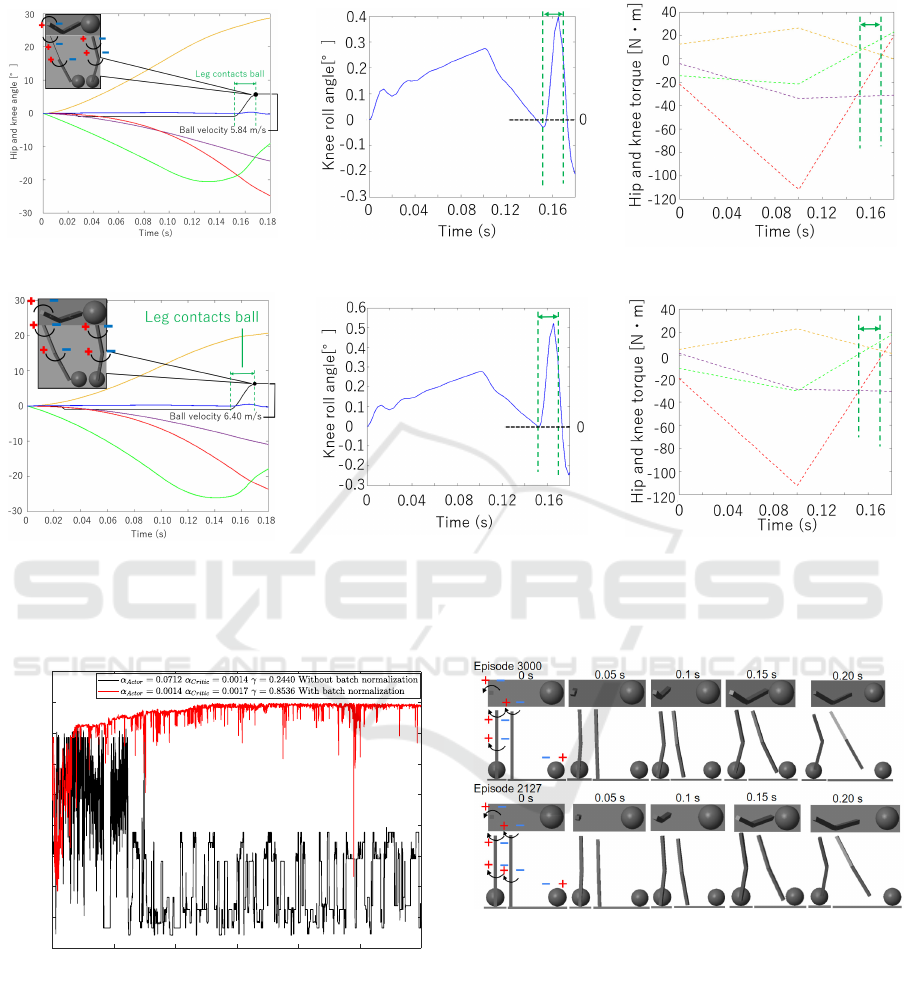

Figure 7: Ball velocity (black, (A)), thigh roll angle (red, (A)) and shin roll angle (blue, (A)(B)), along with hip roll torque

(black, (C)), at the 3000 episode. Same parameters at the 1826 episode for (D),(E), and (F) in the (a) leg model. The leg

makes contact with the ball between the green dotted lines.

Table 3: Tuned hyperparameters.

Actor learning rate Critic learning rate Discount factor Tuning with/without Batch Normalization

1 0.0712 0.0014 0.2440 Without

2 0.0014 0.0017 0.8534 With

Table 4: Ball velocity at 1826 episode of model (a) and at

2127 episode of model (b).

1826 episode (Model (a)) 2127 episode (Model (b))

6.57 m/s 6.39 m/s

connected layer and the nonlinear functions, Relu and

Tanh function.

In 3000 episode, the shin pitch torque starts at 12.7

N · m, increases to 26.1 N ·m at 0.1 s, and then de-

creases to 9.87 N · m by 0.15 s. The hip roll torque be-

gins at −22.2 N · m, decreases to −111.5 N · m at 0.1

s, and then rises to −30.2 N · m at 0.15 s (Fig. 8(I)).

This corresponds to the stopping the thigh’s acceler-

ation, causing the knee joint to rotate around the roll

axis. The leg makes contact with the ball below the

equilibrium angle of 0 deg ((Fig. 8(H))). The hip yaw

torque starts at −14.6 N · m, decreases to −21.3 N · m

at 0.1 s, and then rises to 6.08 N · m at 0.15 s. This

enables the foot to head outward as the knee joint ex-

tends (Fig. 10). We did not observe pulling the thigh

backward diagonally and the stretching the knee sud-

denly. The ball velocity reaches 5.84 m/s.

In 2127 episode, which achieved the highest

Episode Reward Mean, the shin pitch torque started at

5.21 N · m, increased to 22.8 N · m at 0.1 s, and then

decreased to 9.73 N · m by 0.15 s. The hip roll torque

began at −20.1 N · m, decreased to −111.8 N ·m at

0.1 s, and then increased to −34.6 N · m at 0.15 s.

This reduction corresponds to stopping the thigh’s ac-

celeration. (Fig. 8(L)). This action allows the kinetic

energy to transfer from the thigh to the shin, causing

the knee joint to oscillate around the roll axis (Fig.

8(K)). The leg makes contact with the ball at the equi-

librium angle of 0 deg. The hip pitch torque started at

1.75 N · m, decreasing to −31.0 N · m at 0.20 s. This

facilitates the internal rotation of the foot as the knee

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

500

(G)

(H)

(I)

(J)

(K)

(L)

Figure 8: Ball velocity (black, (G)), thigh roll angle (red, (G)), thigh pitch angle (purple, (G)), thigh yaw angle (green, (G)),

shin roll angle (blue, (G) and (H)), shin pitch angle (yellow, (G)), along with hip roll torque (red, (I)), hip pitch torque (purple,

(I)), hip yaw torque (green, (I)), and knee pitch torque (yellow, (I)) at the 3000 episode. The same parameters are presented

for the 2127 episode in (J),(K), and (L) for the (b) leg model. The leg makes contact with the ball between green dotted lines.

0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000

Number of Training Episode

-700

-600

-500

-400

-300

-200

-100

0

100

200

Episode Reward Mean

Figure 9: Episode Reward Mean for (b) Hip-RollPitchYaw-

Knee-RollPitch Leg Model.

joint extends. The hip joint angles increased mono-

tonically (Fig. 8(J)), and we did not observe pulling

the thigh backward diagonally and the stretching the

knee suddenly. The ball velocity reached 6.39 m/s.

Furthermore, we compared the ball velocity in 1826

episode of model (a) and 2127 episode of model (b),

the model (a) which leverages the stiffness of collat-

Figure 10: Motion snapshots of model (b) at 3000 and 2127

episode.

eral ligaments, produced a faster ball kick than the

model (b)(Table 4). Between the Fig. 7(E) and Fig.

8(K), the knee roll angle oscillates similarly; however,

the interaction phases differ. In the Fig. 8(K), the leg

makes contact with the ball at approximately 0 deg,

while in the Fig. 7(E), the leg exceeds 0 deg, oscil-

lating around the equilibrium angle of the knee. This

joint oscillation, driven by the ligaments, affects on

the ball velocity. These results suggest that utilizing

collateral ligaments leads to a faster ball.

Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer

501

5 CONCLUSION

We confirmed that the agent developed strategies sim-

ilar to an outside pass in soccer. For the leg model (a),

episode 1826 showed stopping the thigh’s accelera-

tion while did not show pulling the thigh backward di-

agonally. 3000 episode included both. In contrast, leg

model (b) demonstrated bending the knee and stop-

ping the thigh’s acceleration at episodes 2127 and

3000, while we did not observe the pulling the thigh

backward diagonally and stretching the knee sud-

denly. Additionally, we observed that the leg model

(a), which utilizes the collateral ligaments’ stiffness,

resulted in a faster ball compared to leg model (b),

which is capable of moving in directions that do

not engage the collateral ligaments’ stiffness. We

achieved better understanding of the joint strategies

in an outside pass where ligaments involve, which is

beneficial for developing strategies to kick faster ball

with small motion. For future work, we aim to inves-

tigate whether oscillation around the roll axis of the

knee joint occurs in human. Additionally, we plan to

further explore strategies involving muscle strength-

ening and knee joint oscillation in other sports, such

as tennis and volleyball.

REFERENCES

Aeles, J. and Vanwanseele, B. (2019). Do stretch-

shortening cycles really occur in the medial gastroc-

nemius? a detailed bilateral analysis of the muscle-

tendon interaction during jumping. Front Physiol.

Asaoka, T. and Mizuuchi, I. (2017). Generation of the

swing motion pattern of a multi-link robot for the ex-

plosive increase of the kinetic energy of the end-link

by exploiting dynamic coupling. Transactions of the

JSME (in Japanese).

Cerrah, A. O., Gungor, E. O., Soylu, A. R., Ertan, H., Lees,

A., and Bayrak, C. (2011). Muscular activation pat-

terns during the soccer in-step kick. Isokinetics and

Exercise Science.

Chiras, D. D. (2018). Human Biology. Jones Bartlett Learn-

ing.

Christenson, A. J. and Casa, D. J. (2020). Analysis on the

effect of ball pressure on head acceleration to ensure

safety in soccer. Proceedings.

Dhaher, Y. Y. and Francis, M. J. (2006). Determination

of the abduction-adduction axis of rotation at the hu-

man knee: helical axis representation. Journal of or-

thopaedic research : official publication of the Or-

thopaedic Research Society.

Dibrezzo, R., Gench, B. E., Hinson, M. M., , and King, J.

(1985). Peak torque values of the knee extensor and

flexor muscles of females. The Journal of orthopaedic

and sports physical therapy.

Fukasawa, S. (2000). Biomechanics in stretch-shortening

cycle exercise. Japanese Society of Physical Educa-

tion.

Grondman, I., Busoniu, L., Lopes, G. A. D., and Babuska,

R. (2012). A survey of actor-critic reinforcement

learning: Standard and natural policy gradients. IEEE

Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part

C (Applications and Reviews).

Herman, I. P. (2009). Physics of the Human Body Biological

and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering. NTS.

Ho-Jung, C. and Dai-Soon, K. (2020). Mechanical proper-

ties and characteristics of the anterolateral and collat-

eral ligaments of the knee. Applied Sciences.

Hondo, T. and Mizuuchi, I. (2012). Realization method

of high kinetic energy utilizing elastic joints based on

feedback excitation control and analysis of equal en-

ergy hypersurfaces. Proceedings of the 2012 JSME

Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics.

Ishii, H., Yanagiya, T., Naito, H., Katamoto, S., and

Maruyama, T. (2009). Numerical study of ball behav-

ior in side-foot soccer kick based on impact dynamic

theory. J Biomech.

Ker, R. F., Bennett, M. B., Bibby, S. R., Kester, R. C., and

Alexander, R. M. (1987). The spring in the arch of the

human foot. Nature.

Kozo, N. and Takeo, M. (2006). A 3d dynamical model

for analyzing the motion-dependent torques of upper

extremity to generate throwing arm velocity during an

overhand baseball pitch. Jpn J Biomechanics Sports

Exerc.

Kozo, N., Yosuke, F., and Takeo, M. (2007). Analysis of

mechanical energy generation, transfer and causal en-

ergy sources in soccer instep kick. The Proceedings of

Joint Symposium: Symposium on Sports Engineering,

Symposium on Human Dynamics.

Lanza, M. B., Rock, K., Marchese, V., Addison, O., and

Gray, V. L. (2021). Hip abductor and adductor rate

of torque development and muscle activation, but not

muscle size, are associated with functional perfor-

mance. Frontiers in Physiology.

Levin, A., Wyman, J., and Hill, A. V. (1927). The viscous

elastic properties of muscle. Proceedings of the Royal

Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a

Biological Character.

Li, G., DeFrate, L. E., Sun, H., and Gill, T. J. (2004). In

vivo elongation of the anterior cruciate ligament and

posterior cruciate ligament during knee flexion. The

American journal of sports medicine.

Lillicrap, T. P., Hunt, J. J., Pritzel, A., Heess, N., Erez, T.,

Tassa, Y., Silver, D., and Wierstra, D. (2019). Contin-

uous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv.

Lindsay, D. M., Maitland, M., Lowe, R. C., and Kane, T. J.

(1992). Comparison of isokinetic internal and external

hip rotation torques using different testing positions.

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

Nagurka, M., , and Huang, S. (2004). A mass-spring-

damper model of a bouncing ball. Proceedings of the

2004 American Control Conference.

Pontaga, I. (2004). Hip and knee flexors and extensors bal-

BIOINFORMATICS 2025 - 16th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms

502

ance in dependence on the velocity of movements. Bi-

ology of Sport.

Senoo, T., Namiki, A., and Ishikawa, M. (2008). High-

speed throwing motion based on kinetic chain ap-

proach. 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on

Intelligent Robots and Systems.

Tomohisa, M., Norihisa, F., Michiyoshi, A., Yasuo, K., and

Morhihiko, O. (1997). A three-dimensional analysis

on mechanical energy flows of torso and arm segments

in baseball throw. Japanese Journal of Physical Fit-

ness and Sports Medicine.

Wiesinger, H. P., Rieder, F., K

¨

osters, A., M

¨

uller, E., and

Seynnes, O. R. (2017). Sport-specific capacity to use

elastic energy in the patellar and achilles tendons of

elite athletes. Front Physiol.

Woo, S. L., Johnson, G. A., and Smith, B. A. (1993). Math-

ematical modeling of ligaments and tendons. Journal

of Biomechanical Engineering.

Xu, C., Ming, A., Maruyama, T., and Shimojo, M. (2007).

Motion generation for hyper dynamic manipulation.

Mechatronics.

Lower Leg Joint Strategies in the Outside Pass in Soccer

503