Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation

to Ensure Narrative Interest

Gonzalo M

´

endez

a

and Pablo Gerv

´

as

b

Facultad de Inform

´

atica, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid 28040, Spain

Keywords:

Agent-Based Simulation, Affinity Driven, Narrative Generation, Story Sifting, Romantic Interest.

Abstract:

Multi-agent systems have become important sources of inspiration for narrative generation systems, with

significant growth in solutions based on story sifting: identifying the subset of events generated by such

a system that is worthy of being told as a story. Existing systems simulate the romantic behaviour of agents

based on simple rules that consider models of social norms and relations, and the evolution of affinities between

agents. The present paper describes an extension to one such simulation that inserts several sources of conflict

between characters to induce more interesting situations that allows the creation of more engaging stories. The

system is empirically shown to give rise with much higher scores on metrics for narrative interest.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the challenges of Artificial Intelligence during

the last decades has focused on the generation of qual-

ity narrative texts. With the development of LLMs,

the appearance of the generated texts has improved

dramatically, but the quality of the stories created by

these models still has much room for improvement.

One possible approach to generate interesting stories

is to run agent-based simulations to model human be-

haviour and then pick out of the resulting set of events

a subset that constitutes an interesting story. This

would be equivalent to simply observing how peo-

ple behave around us and identifying the particular

situations that make for an interesting story. How-

ever, in real life the percentage of events that happen

around us that is valuable as material for stories is

considerably low. If the simulation chosen as object

of our study models real human behaviour closely, we

may be faced with a similar situation. Human au-

thors more often apply different strategies, either ex-

agerating or extrapolating beyond the behaviours they

do observe in real life, or merging together remark-

able fragments of ordinary lives into fictional lifes that

pack more interest than real humans usually observe.

The present paper explores measures for enriching

or tuning an agent-based simulation to ensure that the

logs of events that result contain material that may be

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7659-1482

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4906-9837

valuable to inspire an interesting story. As a relevant

case study, the simulation on which we operate fol-

lows a set of characters that interact, focusing on the

evolution of affinities and romantic relations between

them.

2 RELATED WORK

Two topics need to be reviewed to inform the work

in this paper: existing simulations that contemplate

affinities and relations between characters, and efforts

to sift through the logs of simulations in search of in-

teresting stories.

2.1 Simulations Involving Romance

There have been several computational systems that

model situations of affective engagement between

characters. Some of them have been developed as in-

teractive fiction applications (Mateas and Stern, 2005;

Szilas, 2003), some as models of social interaction

(McCoy et al., 2014) to support games (McCoy et al.,

2010) or narratives (Porteous et al., 2013a), some as

models of emotional response to support training en-

vironments (Gratch, 2000), some directly aimed to

support the generation of narratives, whether based on

evolving affinities between characters (P

´

erez y P

´

erez,

1999; Theune et al., 2003; M

´

endez et al., 2014) or

conflict (Ware et al., 2014; Fendt and Young, 2017).

Méndez, G. and Gervás, P.

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest.

DOI: 10.5220/0013308800003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 2, pages 693-703

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

693

The Fac¸ade system (Mateas and Stern, 2005;

Strong and Mateas, 2008) was an interactive narra-

tive in which the participates in a dinner party at a

couple’s home, gets to participate in the conversa-

tions, and partly experiences and partly determines

the evolution of tensions between the couple. Fac¸ade

was a very realistic system based on a pre-determined

scripts structured as a set of beats, with the system

choosing among them based on the typed contribu-

tions by the user. The system modelled the affinities

between the characters and relied on elaborate models

of how dialogue contributions influenced them.

The IDTENSION system (Szilas, 2003) was also

an interactive narrative engine designed to construct

interesting behaviour for a set of characters, relying

on a model that accounted for character goals, obsta-

cles on their path, and the moral values that sustained

them. To attain interest, the system faced characters

with potential actions that conflicted with their moral

values.

The Comme il Faut (CiF) (McCoy et al., 2014)

system was a knowledge-based model of social in-

teractions that attempted to account for the complex

interplay between social norms, character desires and

cultural background. It considered a micro-theory of

friendship and it proposed a set of rules to capture the

possible behaviours of characters faced with partic-

ular social situations. The Comme il faut system has

been used to build the game PromWeek (McCoy et al.,

2010; McCoy et al., 2013a; McCoy et al., 2013b), in

which players live out the week before the prom and

have to achieve a particular set of goals in that time.

The game evolved from an initial version focused on

the pyschological needs of individuals within the so-

cial context to a later version that focused on the logic

of social statuses and relationships between charac-

ters.

The NetworkING (social Network for Interactive

Narrative Generation) system (Porteous et al., 2013a;

Porteous et al., 2013b; Porteous et al., 2015) was a

system for interactive narrative for a medical drama

with a cast of doctors, nurses and patients. It relies

on a representation of the social relationships between

characters as a network, and it has the story evolve as

these relations change dramatically over time. The

relationships considered are affective (six graded cat-

egories: friend, close-friend, long-term-close-friend,

antagonist, extreme-antagonist, long-term-extreme-

antagonist, professional-rival), romantic (five cate-

gories with subtle differences: long-term-partner,

dating, secretly-dating, attracted-to, romantic-rival)

and a default relationship that covers indifference. A

planner is used to determine the actions each char-

acter takes, based on and affecting the relationships

between them.

The

´

Emile system (Gratch, 2000) was also an in-

teractive system that relied on a model of affective re-

sponse to situations, in this case applied to simulation

for military training and pedagogical agents. Agents

in the system monitor the environment and periodi-

cally update a model of their emotional state, which is

taken into account when determining their behaviour.

The model for Emile considers significant psycholog-

ical theories of emotional appraisal. However, it stops

short of considering issues of romantic attachment be-

tween characters.

The MEXICA system (P

´

erez y P

´

erez, 1999) gen-

erated short sequential narratives about the Mexicas,

ancient inhabitants of Mexico City. To do this it re-

lied on a representation of the affinities and tensions

between characters, which are used to drive the con-

struction of the story based on knowledge structures

that capture examples of evolution of affinities and

tensions over existing prior stories.

The Virtual Storyteller system (Theune et al.,

2003) was a multi-agent system designed to gener-

ate short fairy tales. It has an underlying storyworld

in which agents interact to achieve goals. In so doing

they experience emotions, which affect their subse-

quent actions. To ensure the resulting storyworld in-

cludes material useful for telling stories about it, two

different mechanisms are overlaid on agent simula-

tion: (1) the actions of agents are constrained by a

model of plot (to ensure that stories are consistent)

and (2) a special director agent is added to guide the

actions of the other agents towards a well-structured

plot. The director agent can intervene in the simula-

tion in one of three ways: by inserting new characters

or objects into the story world, by infusing charac-

ters with new goals, by blocking actions that a char-

acter intends to do. The Virtual Storyteller was built

as a multi-agent framework running on JADE (Java

Agent Development Environment (Bellifemine et al.,

2005)).

Further systems that rely on elaborate models of

agent behaviour rely on conflict between agents, mod-

elled as clashes between agents plans modelled ex-

plicitly by means of planners. One such system was

the Glaive system (Ware et al., 2014), which informed

an interactive game where the user would come up

with a plan to carry out a simple task and then the sys-

tem would attempt to find ways of thwarting that plan.

A similar mechanism was employed by the IRIS sys-

tem (Fendt and Young, 2017) which constructed plots

featuring conflict by iterating over a cycle in an orig-

inal plan for the protagonist was built, then come up

with countermeasures that would thwart the plan so

that the protagonist would need to replan. The IRIS

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

694

system relied on a belief desire intention (BDI) model

of the protagonist. However, none of these systems

based on planning considers situations of romantic in-

terest.

Charade (M

´

endez et al., 2016) is a multi-agent

simulation (also based on JADE (Bellifemine et al.,

2005)) driven by a model of interpersonal affinities

between characters and how they evolve over time.

The system represents affinities on a scale of foe, in-

different, friend and mate. The system explicitly con-

siders situations of romantic interest between pairs of

characters, and models how affinities between them

evolve based on how they respond to proposals for

joint activities. A set of rules governs how agents be-

have based on their standing set of affinities and how

these affinities change based on character behaviour.

A simulation is run with 15 agents who do not all

know each other. Each agent may or may not have

a partner, a small set of friends (between 2 and 4) and

may or may not have any enemies (1 or 2 at the start).

Interactions are driven by affinities between charac-

ters, and also act upon them. Probability of interac-

tion is highest for partners, lower for friends, and low-

est for enemies. Acceptance of proposals raises affin-

ity between the characters, rejections and inactivity

lower it. The result is a log of interactions and evo-

lutions of affinity levels which are subsequently used

to generate episodes within a narrative (Concepci

´

on

et al., 2018).

Affinities between two agents A and B are di-

rected, so what A feels for B may differ from what

B feels for A. They are represented on a scale be-

tween 0 and 100, with 0 representing strong dislike

and 100 representing passionate love. The Charade

system considers a classification of relations between

agents in terms of the affinities between them: foe

affinity between 0 and 40, neutral affinity between 40

and 60, friend affinity between 60 and 80 and mate

affinity between 80 and 100.

The type of relation that holds between two agents

determines the subset of activities that they may con-

sider together.

Each agent contributes to the general evolution of

the simulation by: (a) proactively proposing inter-

actions to other agents or reacting to proposals re-

ceived, and (b) by registering changes in affinity to-

wards other agents in response to proposals or reac-

tions. The behaviour of agents is informed by the

affinities between them, and it also has the potential

to alter the affinities between them.

2.2 Story Sifting

The idea of generating narrative by telling about se-

lected subsets of events arising from an agent-based

simulation evolved over time into a research line

specifically focused on modelling this process of se-

lection of interesting events to tell. This research line

has come to be known as story sifting. The term was

proposed in James Ryan’s PhD thesis (Ryan, 2018)

as the task of curating interesting narratives out of the

logs for simulations, usually agent-based. Many of

the early approaches to this task relied on procedures

for trawling through the available events in search for

subsequences that satisfy patterns of plot known to be

interesting (Kreminski et al., 2019; Kreminski et al.,

2021).

The application of evolutionary solutions for sift-

ing interesting stories about romantic entanglements

(Gerv

´

as and M

´

endez, 2023) from the Charade agent-

based simulation (M

´

endez et al., 2016) operated by

developing a set of metric on relative narrative in-

terest from the point of view of romance to a se-

lection of events made over a log of a system run.

The described algorithm was shown to achieve rela-

tively good scores on those metrics, but the overall

values were seen to be restricted by the level of inter-

est achieved by the simulation. Runs of the system

were shown to have a relative variation of affinities

between agents at the start but eventually converge to

rather low values of affinity between all couples tak-

ing part in the simulation. Although this may appear

to be realistic in terms of modelling personal experi-

ence of individuals (Alsawalqa, 2019), it leads to sto-

ries that are not as interesting as we could have hoped.

We therefore consider that the agent-based sim-

ulation might produce more interesting material for

subsequent selection aimed at obtaining interesting

narratives if the behaviour of agents could somehow

be tweaked towards situation more interesting from

the point of view of narrative. To inform such a

task, we consider candidate theories that might pro-

vide clues as to what situations among romantic part-

ners may lead to interesting narratives.

3 UPGRADING THE NARRATIVE

INTEREST OF A SIMULATION

The starting point for the work described in this paper

is the Charade system reported in section 2.1 (M

´

endez

et al., 2016). The simulation is made up of 3 types of

agents that allow the development of the interactions

necessary to simulate an environment of romantic re-

lationships between the characters: The Logger Agent

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest

695

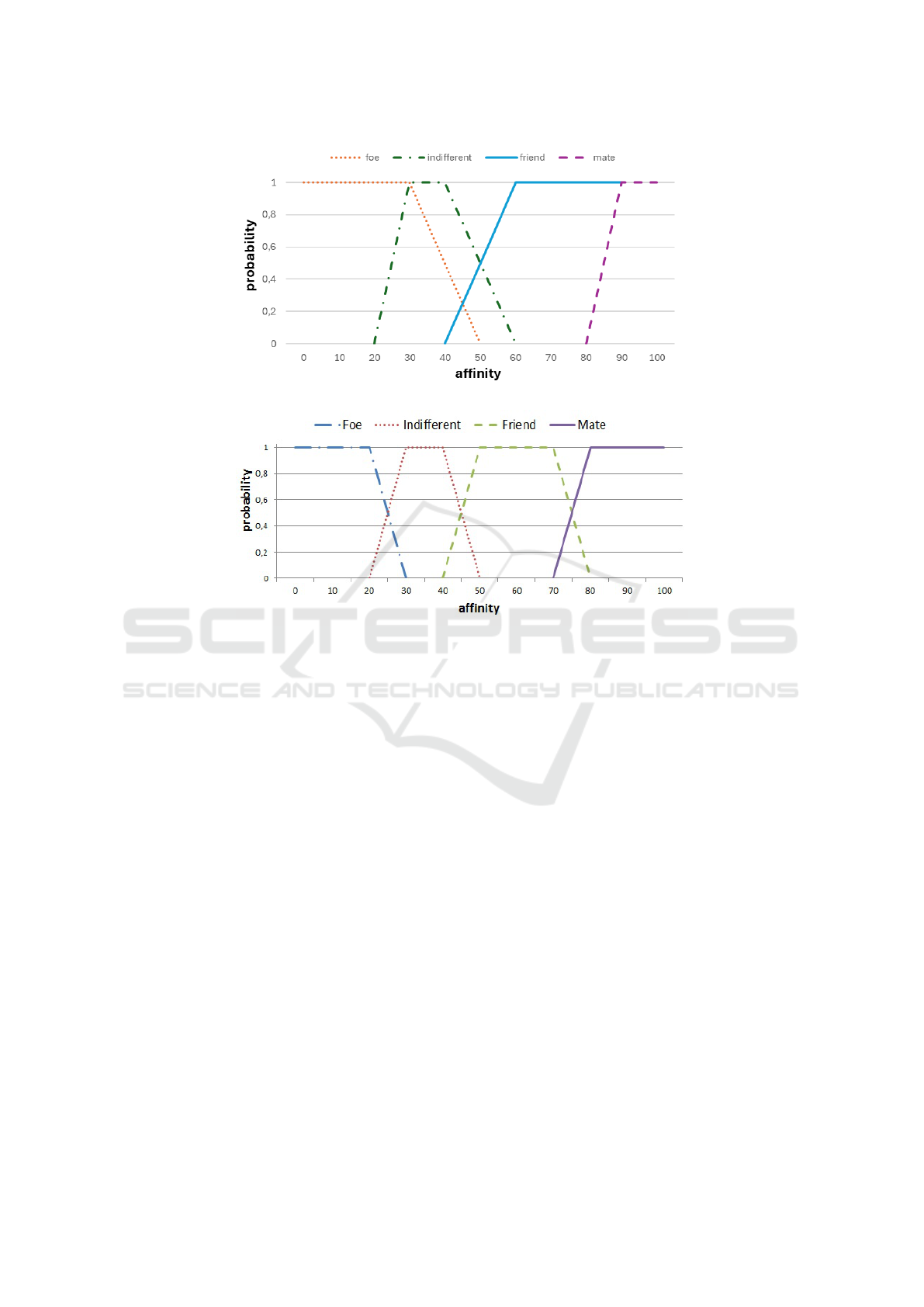

Figure 1: Transition of affinities between characters.

Figure 2: Original transition of affinities between characters.

allows collecting all the events triggered by the rest of

the agents and filtering and formatting those that are

of interest to build the simulation log that is used to

generate the stories; the Director Agent is in charge

of loading the initial situation of the simulation and

creating all the characters that will intervene in it; and

the Character Agents, one for each character in the

plot, whose responsibility is to interpret the state of

the relationships with the other characters and decide

how to interact with them in order to develop the plot

of the story. In turn, these characters are endowed

with a series of behaviors that are executed in a cycli-

cal manner that allow them to send messages to each

other and react to the messages they receive depend-

ing on the relationship they have with the character

sending the message.

A preliminary analysis of the logs generated by

the original simulation shows that of the 23 bidirec-

tional relationships between the 15 characters exist-

ing in the initial situation of the simulation, most

of them decay into a relationship of indifference be-

tween them, which leaves the state of the simula-

tion in a fairly stable situation but which, in narrative

terms, quickly ends up being of no interest. This anal-

ysis is confirmed by the subsequent results described

in (Gerv

´

as and M

´

endez, 2023) where it can be seen

that the story sifting process on the simulation logs

manages to obtain a few interesting events that allow

to extract an attractive narrative from the simulation

logs.

From this starting point, four sources of conflict

have been introduced into the simulation to make it

more dynamic and increase the likelihood of creating

situations that make the narrative more interesting.

3.1 Customising Reaction Thresholds to

Maximize Interest

The first step in achieving greater dynamics in the

relationships between characters has been to empir-

ically modify the thresholds for switching from one

type of affinity to another. The values that have shown

to be most promising, as shown in Figure 1, substan-

tially modify those of the original simulation (see Fig-

ure 2), introducing a greater overlap and a more grad-

ual transition between them, making it possible for

changes between affinities to occur more frequently.

As can be seen by comparing both figures, an at-

tempt has been made to have a greater overlap be-

tween the different affinities, so that the change from

one to the other is not so predictable and there is even

the possibility on occasions of skipping intermediate

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

696

states, such as the possible change from foe to friend

or vice versa. Mate-type relationships used to be too

stable and took away interest from the stories, so their

amplitude has been reduced and, as will be explained

later, the range of actions that make it possible for

a couple to break up and change their status to one

of the other affinities has been widened. This causes

that, with the change of affinity, the actions performed

by the characters have a greater variety and that these,

in turn, cause a greater impact on the variation of the

affinities.

3.2 Adapting Criteria to Prioritize

Reactions to Other Characters

The second change that has been introduced over the

initial simulation is the criterion used by each charac-

ter to decide whether to make a proposal to another

character or to accept or reject one of these proposals

from another character. In the initial simulation, this

decision was made by setting a probability threshold

and generating a random number. If the generated

number exceeds the threshold, then the proposal is

launched or the received proposal is accepted; oth-

erwise, the proposal is not made or the received pro-

posal is rejected, with consequent modifications be-

tween the affinities of the characters.

As a new source for conflict, the thresholds for

deciding to react have been slightly modified to allow

for more interactions between characters. The most

relevant changes that have been made are:

• In the original simulation, the interactions be-

tween friend characters outnumbered by far the

rest of the interactions (about 90% of the inter-

actions took place between friends). The proba-

bility to initiate or accept friend interactions has

been lowered from 0.7 to 0.4, so that less inter-

actions among friends take place and there is a

higher chance that other kinds of interactions take

place.

• The probability of accepting a mate proposal has

been increased from 0.4 to 0.7, so that more pro-

posals are accepted and, as a consequence, more

break-ups with previous mates take place and

more transitions from mate to foe can occur, giv-

ing rise to more dramatic events to take place.

• The probability of getting angry after a break-up

has increased from 0.4 to 0.6. This, together with

the previous change, make it possible for more

couples (but not too many) to dissolve in an un-

friendly manner, which in turn provides a higher

number of dramatic changes that may create more

engaging situations.

• In the first version of the simulation, interactions

with friends and mates were prioritized, so in-

teractions with indifferent characters were almost

nonexistent. The probability to interact with these

characters has increased from 0.4 to 0.7, so that

the chance to meet new characters or interact with

a wider range of them is now higher, therefore

making it possible to interfere in other character’s

lives.

• The probability to interact with a foe has been de-

creased from 0.4 to 0.2. Previously, it was less

probable to relax the affinities between two foes,

so once two characters started being foes, their

affinity state rarely changed. This, in some oc-

casions, made the relationships between charac-

ters to get stuck and turned the simulation into an

uninteresting succession of foe events. With this

change, foe relations tend to evolve towards an in-

different state that make it possible for foe charac-

ters to turn into friends or, eventually, form a new

couple.

In addition, the probability on which the decision

of whether to interact with another character is based

in the enhanced version is now computed as the prod-

uct between the value of the random number gener-

ated and the affinity with the character with which one

interacts, so that the probability of interacting with

characters with which one has a higher affinity in-

creases, while the probability of interacting with those

with which one has a lower affinity decreases.

3.3 Monitoring and Intervention to

Avoid Stabilization

The third source of conflict that has been introduced

in the simulation, and the main one, is the intentional-

ity of the characters when deciding with which other

characters they interact and with what objective this

interaction is carried out. For this purpose, the Direc-

tor Agent of the simulation has been provided with

the capacity to supervise the evolution of the affini-

ties between the different characters in the simulation.

This allows, on the one hand, to detect when the ac-

tions taking place in the simulation begin to lose inter-

est because they remain in too stable values. At that

moment, the Director Agent selects a character and

instructs it to increase the probability of interacting

with another character in order to modify its degree

of affinity with that character.

The monitoring and intervention of the Director

Agent is carried out in three steps in order to avoid the

stabilization of the relationships between characters:

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest

697

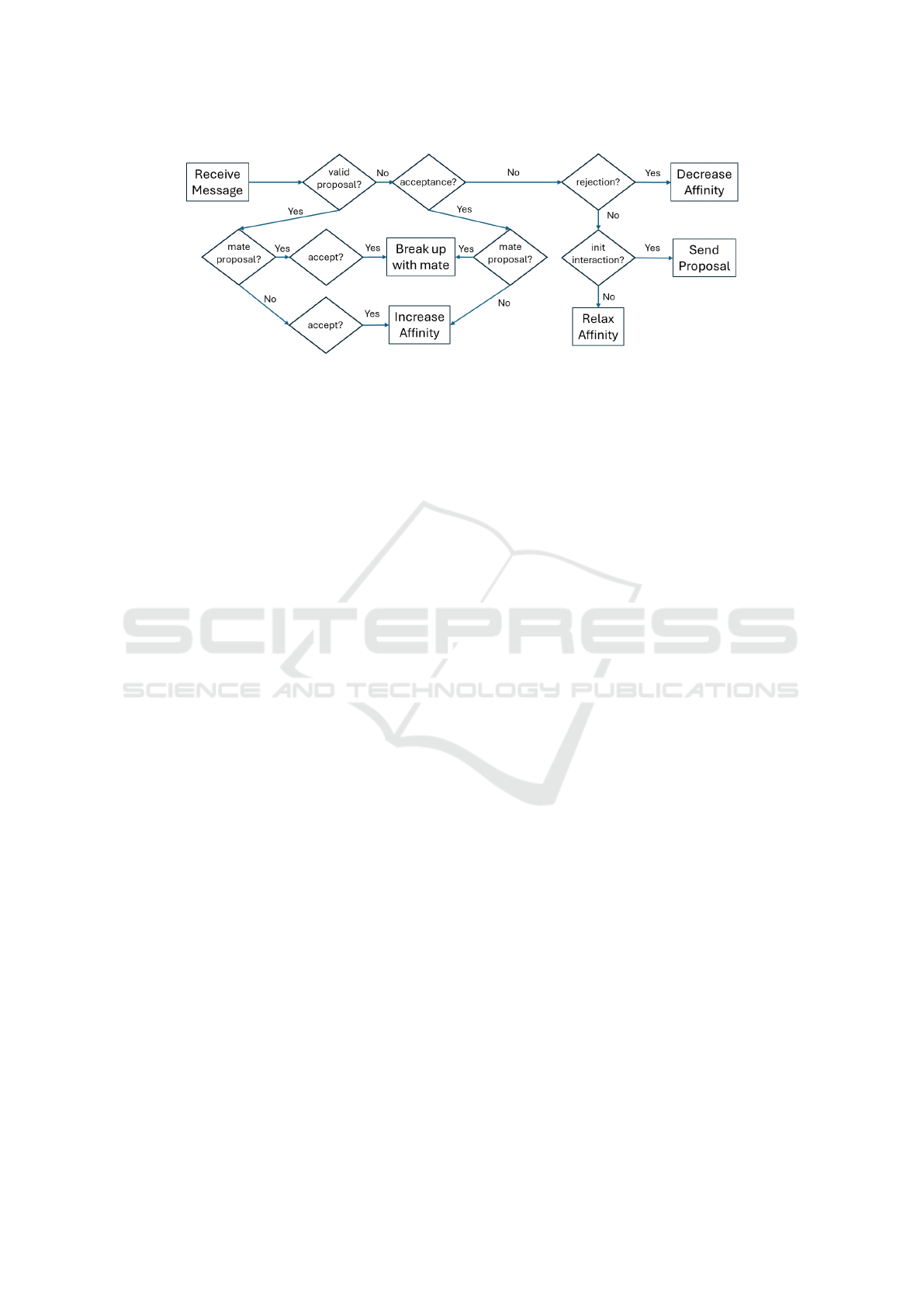

Figure 3: Flow diagram of the Friend Protocol in the enhanced simulation, showing the new possibility of switching from the

preceding partners to a friend with which affinity has reached a sufficiently high value.

1. Supervision: the Director Agent is informed about

all the interactions between each existing pair of

characters - initially, not all characters know each

other, so the number of monitored relationships

depends on the initial configuration of the simu-

lation and the number of new characters that are

met while the simulation runs - and takes note of

all the changes in the affinities. Since affinities in-

crease with interactions and slowly decrease with

the lack of them (or the other way in the case of

foes), it is usually the case that the affinity val-

ues fluctuate between the limits of an affinity level

(e.g. friends) for a long period without anything

exciting happening. To avoid this, the Director

Agent identifies long series of events or periods

of time where the affinity level does not change.

Currently, experimental values are set to 20 inter-

actions or 30 seconds of execution time.

2. Selection: once the described situations are de-

tected, the Director Agent has to select what pair

of characters to act on and where to drive their re-

lationship. In order to do this, the Director Agent

checks the state of the simulation in order to know

how many affinity relations of each kind currently

exist in the simulation and selects the largest one.

Then, among all the relationships that have been

identified as candidates to be modified, it selects

the most stable one in order to act on it.

3. Action: once the pair of characters have been

identified, the Director Agent informs both of

them that they have to modify their interaction cri-

teria until their affinity changes in the following

way:

• they have to stop to select randomly what char-

acter to interact with and they have to focus on

the specific character they have to change the

affinity level

• the probability value to interact with that char-

acter or to accept interactions with that charac-

ter is decreased to 0.1, so that possible interac-

tions are almost nonexistent

• alternatively, if the two characters were close

friends and there are no other restrictions (such

as gender or sexual preferences, which are

taken into account for each character), then the

characters are driven towards trying to become

mates and break up with their current couples,

which automatically generates the possibly in-

teresting sources of conflict (i.e. two break-ups

and a new couple)

• if the existing relation was of indifference, the

characters are driven to change it to friends or

foes, depending on how many relationships of

each kind there are in the simulation

3.4 Increased Affinity with Others

Leading to Couple Break up

The interaction protocol of two characters that are

friends has been modified so that, once a sufficiently

high affinity value is reached between two friends, the

simulation now allows a change of partner between

the characters to occur. To this end, when one char-

acter decides that the level of affinity with another is

sufficiently high, he sends him a proposal to become

his partner. If the other character accepts, each of the

two informs their previous partner that they are break-

ing off their relationship, lowering their affinity level

with them and forming a new partner. In turn, each of

the previous partners decide how much they decrease

their affinity with the partner who has broken the re-

lationship, and can change this affinity to the level of

friend, indifferent or foe. Figure 3 shows the flow di-

agram for the enhanced behaviour.

An example of such an interaction extracted from

the log of one of the simulations can be seen below:

Clark PROPOSE friend_visit_botanical_garden Mary

Mary ACCEPT-PROPOSAL friend_visit_botanical_garden Clark

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

698

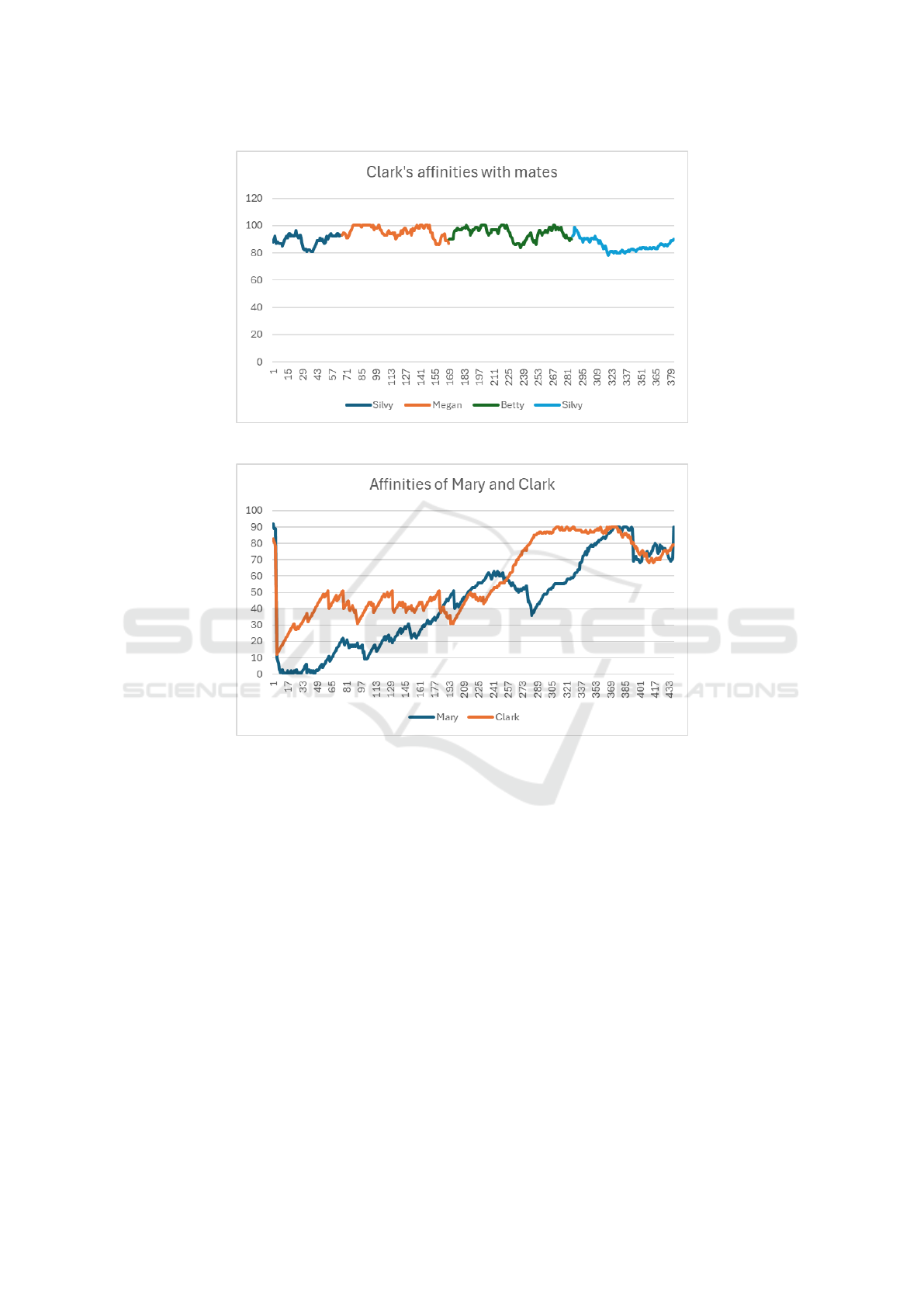

Figure 4: Evolution of the affinities between Clark and his mates.

Figure 5: Evolution of the affinities between characters Mary and Clark.

Mary CHANGE affinity_with Clark 70-->71

Clark CHANGE affinity_with Mary 88-->90

[...]

Clark PROPOSE mate_proposal Mary

Mary ACCEPT-PROPOSAL mate_proposal Clark

Mary CHANGE affinity_with Clark 71-->90

Clark CHANGE affinity_with Mary 90-->90

Clark INFORM mate_break_up Betty

Mary INFORM mate_break_up John

Betty CHANGE affinity_with Clark 92-->15

John CHANGE affinity_with Mary 87-->62

As shown in Figure 4, this new behavior makes

it possible for various changes between existing cou-

ples to occur throughout the simulation, which was

not previously possible. This, in turn, results in that

the relationship between two characters can vary dras-

tically, as can be seen in Figure 5, where, as a conse-

quence of a change of partner of one of the characters,

both change the value of their affinity to be considered

enemies. The relationship between these two charac-

ters evolves in a parallel, but asymmetrical manner,

until eventually they both become friends again.

3.5 Neural Rendering of Selected

Behaviour

The ultimate goal is the ability to create stories from

what happens in the simulation. As we have seen with

the recent development of Large Language Models

(LLMs), these models are capable of generating high

quality text, but it is more complex to be able to con-

trol what these systems generate. This has become

especially apparent in the case of story generation,

where narrative richness and consistency in generat-

ing stories of a certain size has not yet produced the

results that can be seen in other areas. On the other

hand, in the area of story generation, as shown in sec-

tion 2.1, significant progress has been made in gen-

erating stories with great narrative richness, although

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest

699

the quality of the final text, in most cases, was quite

poor.

In the case at hand, we have combined the out-

put generated by our simulation with an LLM, namely

ChatGPT-4o

1

, to generate a story whose development

can be driven in a way by the simulation output and

simultaneously presented in text format with a rich

narrative. A sample prompt we have used for this gen-

eration is

I am going to provide you with the log of a simulation and I need

you to transform it into a short story. The requirements for the

story are:

* Write a brief introduction to the story

* Set the story in some scenario extracted from the log

* Use only the characters and events from the log

This is the log:

<log>

An example with the log shown above is as fol-

lows:

In the heart of the bustling city, nestled amidst towering

skyscrapers, lay the serene Riverside Botanical Garden. A peace-

ful oasis where vibrant blossoms and the soothing rustle of leaves

created a haven away from the urban noise. It was here, on a

warm spring afternoon, that Clark found himself standing by the

entrance, his heart racing with a mix of anticipation and hope.

”Mary,” Clark began, his voice steady but soft, ”would you

like to visit the Botanical Garden with me today?”

Mary’s eyes lit up at the suggestion, and she responded with a

warm smile. “Of course, Clark. I’d love to,” she replied, accept-

ing his invitation. The two friends strolled down the meandering

paths, surrounded by bursts of color from the blooming flowers.

As they wandered through the fragrant air, their bond deepened.

For Mary, her affection for Clark grew just a little stronger, her

feelings blooming like the roses around them. Clark, too, felt the

pull of a stronger connection, and his heart swelled with affection.

Suddenly, a quiet moment by the koi pond turned into some-

thing much more meaningful. Clark took a deep breath and turned

to Mary. “Mary,” he said earnestly, “will you be more than just my

friend?” His voice was sincere, hopeful, and full of vulnerability.

Mary paused, her gaze meeting his, and her heart swirled with

emotions as she gave a gentle nod. “Yes, Clark. I will,” she whis-

pered, sealing their newfound commitment. The garden around

them seemed to glow even brighter as their love blossomed in uni-

son. Their connection was no longer just a friendship but some-

thing richer and deeper. In that magical moment, Mary’s affection

surged, reaching the same height as Clark’s. Their hearts were

fully in sync.

Yet, every new beginning brings change. Knowing what they

had to do, Clark and Mary exchanged difficult messages to their

former partners. Clark informed Betty of their separation, while

Mary had a similar conversation with John. As the news traveled,

old affinities shifted like autumn leaves falling from branches:

Betty’s bond with Clark crumbled, and John’s connection to Mary

dimmed, leaving behind memories of what once was.

And so, amidst the blossoms and the whispering leaves of the

Riverside Botanical Garden, a new chapter began for Clark and

Mary, a story of love born from friendship, growing ever stronger

beneath the open sky.

1

https://openai.com/index/hello-gpt-4o/

The example presented above shows how the text

rendering recounts the basic changes between the af-

fections of the characters that result from the simu-

lation model, while adding a significant amount of

detail on the particular scenes that lead to the differ-

ent changes in affinity. This is considered a valuable

combination of the advantages of the technologies for

agent-based simulation and neural text generation.

4 DISCUSSION

The enhanced simulation proposed in this paper can

be discussed in terms of the advantages it introduces

and in terms of how it compares with previous work

on related topics.

4.1 Advantages of the Enhanced

Simulation

The enhanced simulation, by construction, now

avoids important shortcomings of the original simu-

lation.

Of the modifications introduced in the enhanced

simulation, not all respond to the same motivation.

Some of the changes may be considered as im-

provements that make the simulation more realistic.

The preference for interacting with characters towards

which one has stronger affinity, or the possibility of

dissolving an ongoing romantic relationship when the

affinity with a third party increases beyond a given

threshold, both fall under this category.

Other changes can be considered departures from

real behaviour as observed in human couples, and

they would correspond more to the type of interven-

tion that an author inspired by real life events but de-

siring richer situations might apply in powering up

the situations in her story. The adaptation of reaction

thresholds to obtain richer interactions, or the moni-

toring by the Director Agent of stable situations that

may lead to direct interventions on the probability of

characters interacting would correspond to this sec-

ond category.

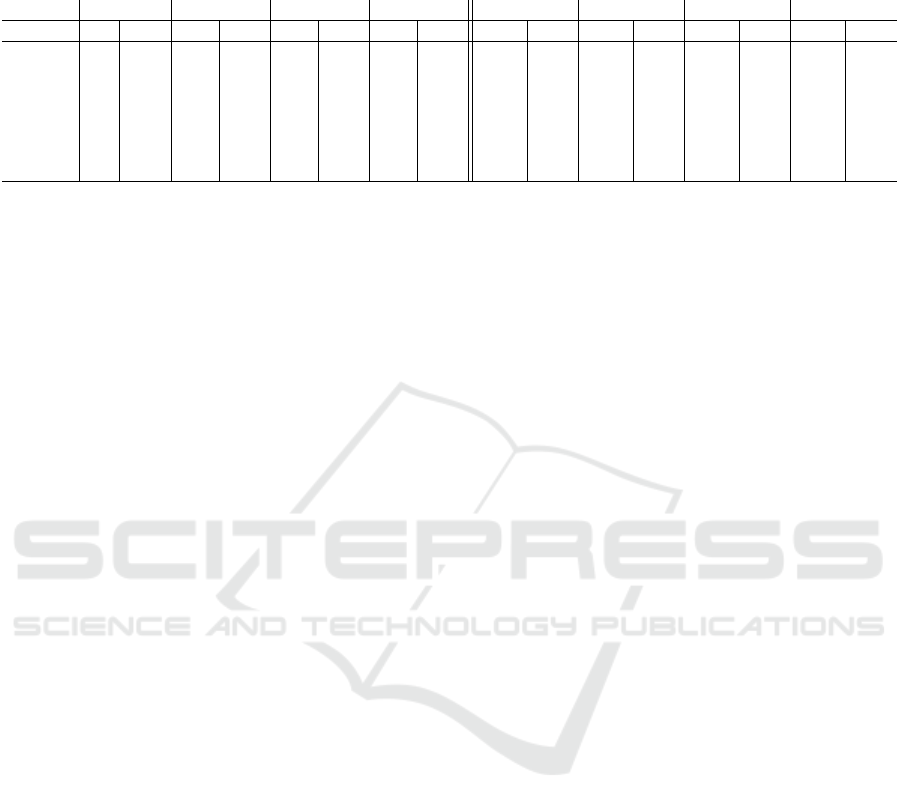

Table 1 shows data from different runs of the

simulations grouped by the version of the simula-

tion used (the first four stories were generated with

the original simulation, while the last four were gen-

erated with the version described in this paper) and

sorted by simulation length. The PROPOSE, AC-

CEPT and REJECT rows refer to interactions be-

tween mates, friends and indifferents, while the IN-

FORM row shows interactions between foes. The

break-ups row shows the number of break-ups that oc-

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

700

Table 1: Simulation data sorted by simulation length. The first 4 stories have been generated using the original simulation,

while the last 4 stories include the modifications described in this paper. Column n shows the number of interactions of each

kind, while column % shows the percentage that each type of interaction represents out of the total number of interactions.

story0 story1 story2 story3 story4 story5 story6 story7

n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n %

PROPOSE 317 46,14 667 49,44 1011 24,71 1074 13,78 7976 64,57 8988 48,37 9545 58,36 10585 54,97

ACCEPT 151 21,98 375 27,80 420 10,27 448 5,75 2230 18,05 4064 21,87 3356 20,52 3641 18,91

REJECT 125 18,20 245 18,16 282 6,89 282 3,62 1733 14,03 3346 18,01 2730 16,69 2770 14,39

INFORM 94 13,68 62 4,60 2378 58,13 5992 76,86 414 3,35 2184 11,75 725 4,43 2260 11,74

break-ups 6 7 7 6 7 11 14 17

affinity

changes

652 1,59 1309 1,80 3789 1,12 7458 1,06 11117 1,33 14162 1,27 17546 1,71 24093 1,88

cur, and the affinity changes row shows the number of

affinity changes over the total number of interactions.

As shown in the table, using the original simula-

tion, as the simulation time increases the percentage

of interactions between mates, friends and indiffer-

ent characters tends to decrease, while the number of

interactions between foes increases notably. On the

contrary, in the stories generated with the simulation

described in this contribution, it can be observed how

the interactions between couples, friends and indif-

ferent people are more numerous and remain more

stable, fluctuating around 60%, while the interactions

between foes fluctuate around 8%.

This has an effect on the number of affinity

changes, which in the case of the original simulation

tends to decrease as the length of the simulation in-

creases while in the case of the new simulation it tends

to double the number of interactions. The latter data

points to a greater tendency to meet new characters

over the course of the simulation and to relax affini-

ties with those characters with whom one character

interacts less. In the case of the initial simulation, this

effect did not occur because the break-ups between

characters led to an increase in interactions between

enemies, which can be appreciated in the increase in

INFORM-type interactions.

Finally, the row relating to break-ups shows how

in the original simulation all or almost all the exist-

ing couples (initially 7) break up due to lack of inter-

est between the members of the couple, while no new

couples are created. In the case of the new simulation,

although the number of break-ups is not very high, the

creation of new couples is a fact that, in due course,

gives rise to new break-ups, so that in the subsequent

story sifting process it is possible to select events that

provide greater interest to the final story.

4.2 Comparison with Prior Work

The Fac¸ade system (Mateas and Stern, 2005; Strong

and Mateas, 2008) differs from the solution presented

in this paper in that it relied on pre-determined scripts.

The Virtual Storyteller system (Theune et al.,

2003) uses a model of plot to constrain the actions of

characters. The system described in this paper differs

from these in that it contemplates a basic set of ac-

tions that can be combined freely to develop complex

behaviours.

The

´

Emile system (Gratch, 2000) operates at a

lower level of representation of relationships, more

concerned with emotional appraisal. The Glaive

(Ware et al., 2014) and IRIS (Fendt and Young, 2017)

systems focus on conflict at the level of the actions

that character want to undertake, but these actions in

general do not involve romantic attachments between

the characters. The system described in this paper op-

erates at a higher level of abstraction, considering ro-

mantic attachments between characters and the social

interactions that may lead to such attachments.

The IDTENSION system (Szilas, 2003) focused

on conflict between actions desired by the charac-

ters and the moral values they aspire to uphold. The

Comme il Faut (CiF) (McCoy et al., 2014) system

evolved from an earlier focus on the psychological

needs of individuals onto the logic of social statuses

and relationships between characters. The simulation

described focuses on romantic relations and it does

not consider conflicting plans, moral values, psycho-

logical needs or social status.

The MEXICA system (P

´

erez y P

´

erez, 1999) relies

on a system for representing affinities between char-

acters, and it drives the construction of its stories by

a set of tensions computed over these affinities. Ten-

sions arise when characters have conflicting values of

affinity to other characters (one character hates and

loves another, or two characters love the same charac-

ter). The system described in this work does not yet

allow us to reflect that type of conflict, although what

it does allow us to reproduce with the new sources of

conflict are situations in which, when a couple breaks

up through the intermediation of a third person, the

characters who have been abandoned have the pos-

sibility of reacting to the breakup in three different

ways: by downgrading their affinity to the level of

friendship and trying to win back their former part-

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest

701

ner, as can be seen in Figure 4; by adopting a position

of indifference; or by displaying a hostile and hateful

attitude and executing actions that reflect this.

The NetworkING (social Network for Interactive

Narrative Generation) system does include romantic

relationships between characters as well as a num-

ber of other possible relations between them, such as

friendship, antagonism or professional rivalry. The

actions of the characters are determined by a plan-

ner that takes into account the network of relations in

which the characters participates. In contrast, the ac-

tions of the characters in the simulation described in

this paper are determined by stochastic process that

operate on the values of affinities between them. This

has been an explicit decision made because, as can

be seen in the analyzed literature (e.g. (Laclaustra

et al., 2014)) and in our own experience developing

story-generating systems (e.g. (Gerv

´

as et al., 2019)),

the use of systems based on rules or planners gen-

erally leads to solutions that tend to always generate

the same story or a very reduced set of them, since

the variability introduced by these solutions is usually

small. In our case, it has been decided to use pseudo-

random decisions to ensure that the variety of situa-

tions that can arise is as wide as possible, since the

subsequent story-sifting process on the log generated

allows us, from among all of them, to select those that

are most interesting depending on the parameters that

are set at any given time. In addition, although appar-

ently the representation of the types of relationships

possible in our system is poorer than the one used in

NetworkING, it seems that the categories used in that

system are closed categories. In our case the affinity

values, although discrete, simulate to be continuous

in comparison, the transitions between categories are

more diffuse and smooth and, above all, the represen-

tation of the affinities used in our system is designed

to make the affinities efficient to calculate, since our

simulation, not being interactive, unlike Networking,

performs many more interactions between characters

per second and needs the calculations of the new val-

ues of the affinities to be performed efficiently.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has shown how four mechanisms have

been successfully introduced to inject conflict into an

agent-based simulation used to create romantic sto-

ries based on the affinity variations that occur between

characters when they interact with each other. These

four mechanisms have been the modification of the

interaction thresholds between characters to achieve

more affinity variations between them; the introduc-

tion of intentionality in the characters when deciding

which character to interact with and what type of in-

teraction to initiate with them; the possibility of hav-

ing the Director Agent directly modify the probability

of interaction between characters to avoid stagnation

into uninteresting situations; and an extension in the

agents’ behavior that allows them to search for a new

partner even at the cost of breaking up with their own

partner and having their new partner break up with

their previous partner as well.

There is still room for improvement in the story

generation system described in this work. As lines

of future work, the following courses of action are

proposed. First, we intend to enrich the representa-

tion of the relationships between characters, introduc-

ing relationships and interactions between more than

two characters and representing the affinities between

them so that contradictory interests may arise (having

a partner with whom one has a low affinity or that a ro-

mantic interest arises with a character one hates). Sec-

ondly, it is proposed to introduce the possibility of the

characters interpreting the existing relationships be-

tween other characters, giving the possibility of mis-

understandings or misinterpretations based on what

one character tells another. Finally, it is also intended

to provide the characters with a more complex model

of personality and emotions, so that each character

can react differently from another to the same situa-

tion, and that this does not depend solely on the gen-

eration of a random value as in the current system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper has been partially funded by the projects

CANTOR: Automated Composition of Personal Nar-

ratives as an aid for Occupational Therapy based on

Reminescence, Grant. No. PID2019-108927RB-

I00 (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation),

project DARK NITE: Dialogue Agents Relying on

Knowledge-Neural hybrids for Interactive Training

Environments, Grant No. PID2023-146308OB-I00

(Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation) and

the ADARVE (An

´

alisis de Datos de Realidad Vir-

tual para Emergencias Radiol

´

ogicas) Project funded

by the Spanish Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear (CSN).

REFERENCES

Alsawalqa, R. O. (2019). Marriage burnout: When the emo-

tions exhausted quietly quantitative research. Iranian

Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 13(2).

Bellifemine, F., Bergenti, F., Caire, G., and Poggi, A.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

702

(2005). Jade—a java agent development framework.

Multi-agent programming: Languages, platforms and

applications, pages 125–147.

Concepci

´

on, E., Gerv

´

as, P., and M

´

endez, G. (2018). Ines:

A reconstruction of the Charade storytelling system

using the Afanasyev framework. In Proceedings of

the Ninth International Conference on Computational

Creativity, Salamanca, Spain, pages 48–55.

Fendt, M. W. and Young, R. M. (2017). Leveraging inten-

tion revision in narrative planning to create suspense-

ful stories. IEEE Transactions on Computational In-

telligence and AI in Games, 9:381–392.

Gerv

´

as, P., Concepci

´

on, E., Le

´

on, C., M

´

endez, G., and De-

latorre, P. (2019). The long path to narrative gener-

ation. IBM Journal of Research and Development,

63(1):8–1.

Gerv

´

as, P. and M

´

endez, G. (2023). Evolutionary story sift-

ing over the log of a social simulation. In Italian Work-

shop on Artificial Life and Evolutionary Computation,

pages 381–393. Springer.

Gratch, J. (2000).

´

Emile: Marshalling passions in training

and education. In Proceedings of the Fourth Interna-

tional Conference on Autonomous Agents, AGENTS

’00, pages 325–332, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Kreminski, M., Dickinson, M., and Mateas, M. (2021).

Winnow: A domain-specific language for incremen-

tal story sifting. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference

on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital En-

tertainment, 17(1):156–163.

Kreminski, M., Dickinson, M., and Wardrip-Fruin, N.

(2019). Felt: A simple story sifter. In Interac-

tive Storytelling: 12th International Conference on

Interactive Digital Storytelling, ICIDS 2019, Little

Cottonwood Canyon, UT, USA, November 19–22,

2019, Proceedings, page 267–281, Berlin, Heidel-

berg. Springer-Verlag.

Laclaustra, I. M., Ledesma, J. L., M

´

endez, G., and Gerv

´

as,

P. (2014). Kill the dragon and rescue the princess: De-

signing a plan-based multi-agent story generator. In

5th International Conference on Computational Cre-

ativity, ICCC 2014, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Mateas, M. and Stern, A. (2005). The interactive drama

fac¸ade. In AIIDE, pages 153–154. AAAI Press.

McCoy, J., Treanor, M., Samuel, B., Reed, A. A., Mateas,

M., and Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2013a). Prom week. In

AIIDE. AAAI.

McCoy, J., Treanor, M., Samuel, B., Reed, A. A., Mateas,

M., and Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2013b). Prom week: De-

signing past the game/story dilemma. In FDG, pages

94–101. Society for the Advancement of the Science

of Digital Games.

McCoy, J., Treanor, M., Samuel, B., Reed, A. A., Mateas,

M., and Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2014). Social story worlds

with comme il faut. IEEE Transactions on Computa-

tional Intelligence and AI in Games, 6(2):97–112.

McCoy, J., Treanor, M., Samuel, B., Tearse, B., Mateas, M.,

and Wardrip-Fruin, N. (2010). Authoring game-based

interactive narrative using social games and comme il

faut. In Proceedings of the 4th International Confer-

ence & Festival of the Electronic Literature Organi-

zation: Archive & Innovate (ELO 2010), Providence,

Rhode Island, USA.

M

´

endez, G., Gerv

´

as, P., and Le

´

on, C. (2014). A model

of character affinity for agent-based story generation.

In 9th International Conference on Knowledge, In-

formation and Creativity Support Systems, Limassol,

Cyprus. Springer-Verlag, Springer-Verlag.

M

´

endez, G., Gerv

´

as, P., and Le

´

on, C. (2016). On the Use

of Character Affinities for Story Plot Generation, vol-

ume 416 of Advances in Intelligent Systems and Com-

puting, chapter 15, pages 211–225. Springer.

P

´

erez y P

´

erez, R. (1999). MEXICA: A Computer Model of

Creativity in Writing. PhD thesis, The University of

Sussex.

Porteous, J., Charles, F., and Cavazza, M. (2013a).

Networking: Using character relationships for in-

teractive narrative generation. In Proceedings of

the 2013 International Conference on Autonomous

Agents and Multi-agent Systems, AAMAS ’13, pages

595–602, Richland, SC. International Foundation for

Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems.

Porteous, J., Charles, F., and Cavazza, M. (2013b). A social

network interface to an interactive narrative. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Au-

tonomous Agents and Multi-agent Systems, AAMAS

’13, pages 1399–1400, Richland, SC. International

Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent

Systems.

Porteous, J., Charles, F., and Cavazza, M. (2015). Using

social relationships to control narrative generation. In

Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth AAAI Conference on

Artificial Intelligence, January 25-30, 2015, Austin,

Texas, USA., pages 4311–4312.

Ryan, J. (2018). Curating Simulated Storyworlds. PhD the-

sis, University of California Santa Cruz, CA, USa.

Strong, C. R. and Mateas, M. (2008). Talking with npcs:

Towards dynamic generation of discourse structures.

In AIIDE. The AAAI Press.

Szilas, N. (2003). Idtension: a narrative engine for inter-

active drama. In Technologies for Interactive Digital

Storytelling and Entertainment. TIDSE 2003 Proceed-

ings, pages 187–203.

Theune, M., Faas, E., Nijholt, A., and Heylen, D. (2003).

The virtual storyteller: Story creation by intelligent

agents. In Proceedings of the Technologies for Inter-

active Digital Storytelling and Entertainment (TIDSE)

Conference, pages 204–215.

Ware, S. G., Young, R. M., Harrison, B., and Roberts,

D. L. (2014). A computational model of narrative con-

flict at the fabula level. IEEE Transactions on Com-

putational Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence in

Games, 6(3):271–288.

Heating up Interactions in an Agent-Based Simulation to Ensure Narrative Interest

703