Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders:

A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

Luigi A. Moretti

1 a

, Miles Thompson

2 b

, Paul Matthews

3 c

, Michael Loizou

4 d

and David Western

1 e

1

UWE Bristol (University of the West of England), School of Engineering, England, U.K.

2

UWE Bristol (University of the West of England), School of Social Sciences, England, U.K.

3

UWE Bristol (University of the West of England), School of Computing and Creative Technologies, England, U.K.

4

University of Plymouth, Faculty of Health, England, U.K.

Keywords: Anxiety Disorders, Affective Computing, Emotion Recognition, Emotion Detection, Social Phobia,

Panic Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD),

Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD).

Abstract: Anxiety disorders (ADs) affect roughly one in ten people in the UK, and this number is expected to increase,

intensifying the need for innovation. Digital technologies such as affective computing (AC, technology to

detect human emotions) could foster a more patient-centric approach, enhancing therapy adherence and

optimizing clinician-patient interactions. This paper reviews the literature relevant to the integration of

affective computing in clinical pathways for ADs. A search was conducted on Google Scholar and PubMed

using the keywords “affective computing” and subtypes of anxiety disorders. A total of 355 results were

filtered to focus on peer-reviewed articles that specifically addressed emotion recognition in pathological

anxiety as opposed to simply feeling anxious. Findings underscore prevalent studies focusing on post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the widespread use of valence and arousal for emotion quantification.

Various approaches for both eliciting and detecting emotions are explored, offering technical and practical

insights. Diverse applications, from monitoring treatment progression in behavioral therapies to assessing the

efficiency of deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder, highlight affective

computing's versatility and promise. A significant advantage of digital technologies is their potential to

capture longitudinal and contextualized data beyond clinical confines. Such assessments elucidate patients'

daily challenges and triggers, enabling tailored interventions. The literature suggests that AC has the potential

to support mental healthcare and improve patient outcomes. However, further evidence of its effective benefits

is required, especially for ADs beyond PTSD, and further exploration of its implementation in clinical

pathways is needed.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to

use digital technologies to support mental health and

well-being (De Witte et al., 2021) and several self-

help solutions are available on the market. However,

the integration of these technologies with clinical

pathways, a more complex yet potentially impactful

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6180-0565

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1358-1962

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1021-2683

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9575-7182

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4303-7423

application, has received relatively little attention.

1.1 Anxiety Disorders, a Clinical

Context

According to a 2007 survey in the UK, the prevalence

of any lifetime mental disorder was 45.5% (Slade et

al., 2009). Additionally, a 2014 survey indicated that

Moretti, L. A., Thompson, M., Matthews, P., Loizou, M. and Western, D.

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0013322800003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 273-284

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

273

approximately one in ten people in the UK are

affected by ADs (Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey,

2014). This situation has been worsened by the

Covid-19 pandemic, in which the necessary

restrictions and social rules introduced (e.g.

lockdowns, quarantines, social distance, etc) have

triggered disorders otherwise somehow controlled,

and sharpened the ones already manifest (Ugbolue et

al., 2020; Shevlin et al., 2020).

In psychiatry there is a continuous debate about

the taxonomy of mental disorders. For a matter of

simplicity, in this text we refer to ‘Anxiety Disorders’

(ADs) based on the definition provided by the U.S.

National Institutes of Mental Health, which includes

five major types (U.S. Department of Health &

Human Services, 2024): Generalized Anxiety

Disorder (GAD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

(OCD), Panic Disorder (PD), Post-Traumatic Stress

Disorder (PTSD), Social Phobia (or Social Anxiety

Disorder, SAD).

Anxiety disorders (ADs) remain significantly

under- and misdiagnosed, partly due to challenges in

distinguishing between subtypes and the prevalence

of co-occurring somatic complaints and

comorbidities. These challenges are particularly

widespread; for instance, comorbidities affect

approximately 90% of patients with obsessive-

compulsive disorder (OCD) (Stein et al., 2019;

Yehuda et al., 2015). Current diagnostic methods face

notable limitations. Standard self-reported

approaches rely paradoxically on patients' ability to

assess their own emotional awareness, a capability

often impaired in ADs (Berking et al., 2011; Berking

& Wupperman, 2012). Structured clinical interviews,

while widely used, frequently lack flexibility,

specificity, and cross-cultural validity. Additionally,

these interviews can fail to detect concealed or

simulated symptoms. For example, only 11% of

PTSD patients are correctly identified through

structured interviews (Yehuda et al., 2015). Beyond

these diagnostic challenges, there is a lack of

objective tools capable of differentiating between

stages of ADs and quantifying their impact on

patients’ quality of life (Stein et al., 2019; Yehuda et

al., 2015). An objective tool is also desirable to

provide data to assess the efficacy of

pharmaceuticals, psychological and alternative

treatments (Bystritsky et al., 2013; Stein et al., 2019;

Yehuda et al., 2015).

Moreover, the healthcare system is under pressure

worldwide due to a shortage of workforce compared

to the increasing demand (Michelutti & Relić, 2022).

This scenario leads to high level of stress and burnout

among the clinicians and to a reduction of time per-

patient. Therefore, more research is needed to

investigate the use of digital technologies to support

patients’ self-management and involvement, as well

as to enable more efficient patient-clinician

interactions.

1.2 Affective Computing in Mental

Health

Emotions are central to the human experience, and

play a crucial role in our lives: they influence our

learning, attention, decision making and perception

(Picard, 1997). From a neurobiological perspective,

emotions are bioregulatory reactions regulated by

chemical and neural responses regarding

‘emotionally competent stimuli’ (i.e. objects,

situations, or memories).

There are mainly two families of classifications

for emotions (Yazdani et al., 2013): 1. Discrete

Emotional Model (DEM) which is a categorical

model based on standard terms used as references,

and the selection of emotions used varies between

studies. Furthermore, there could be cultural biases in

the interpretation of the meaning of each emotion

used. Some of the most common labels used are:

‘anger’, ‘sadness’, ‘joy’, ‘disgust’, ‘surprise’, ‘fear’

(Ekman et al., 1972). 2. Affective Dimensional Model

(ADM) or Continuous Dimensional Model which,

instead, is a system of coordinates for emotions,

which is based on Valence and Arousal for the 2D

models, plus Dominance (Mehrabian, 1997) for the

3D ones (VAD model). The Valence dimension

expresses the degree of pleasantness, while Arousal

captures intensity, ranging from calm to energized;

Dominance is used to represent the level of control

and freedom to act, ranging from submissive to

empowered (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974). Moreover,

some authors (Verma & Tiwary, 2017) proposed a 3D

matrix in which VAD emotion values essentially

serve as coordinates for DEM labels clustered in 5

main groups, bridging the two emotion classification

approaches.

Some researchers emphasise the key role that

affective assessment plays in psychotherapy: both to

assist patients in their therapeutic journey and to

provide the clinician with a framework for

intervention (Greenberg & Safran, 1990). There are

also studies supporting the role of arousal in

facilitating anxiety reduction in fear-avoidance

problems (Greenberg & Safran, 1989), such as PTSD

(Hyer et al., 1991).

Affective Computing (AC) is a multidisciplinary

field which studies emotions through technology

(Calvo et al., 2015). Many studies have explored how

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

274

AC can detect common anxiety, which is the normal

and expected response to everyday challenges or

stress. However, fewer studies have focused on

pathological anxiety, an anxiety that is too intense,

lasts too long, or occurs in ways that disrupt daily life.

This work aims to explore how AC techniques have

been developed and evaluated specifically for ADs.

2 METHODOLOGY

A previous overview of affective computing solutions

in healthcare found that 28.3% of the publications

prior to 2020 were related to mental health, excluding

studies that referred to the use of wearables other than

eye tracking, which differentiates it from the present

work (Apablaza & Cano, 2020). In a 2014 review, 34

studies on digital solutions for anxiety disorders were

examined, emphasizing the Ecological Momentary

Assessment (EMA) approach's ability to provide

insights into the temporal variability of symptoms and

associations among daily affect, behaviors, and

situational cues thanks to the collection of

longitudinal data. The study also noted successful

combinations of EMA with ambulatory assessment of

physiological variables and treatment evaluations

(Walz et al., 2014). Other literature reviews focused

on specific data modalities and/or techniques in come

ADs sub-disorders (e.g. machine learning (ML) for

speech analysis in PTSD (Anitha, 2022; Suneetha &

Anitha, 2024), or fMRI in SAD (Hattingh et al.,

2013)).

The research question that this paper aims to

address can be summarised as follows: How

effectively has affective computing proven to be for

supporting clinical pathways in anxiety disorders, and

what are the technological and pragmatic challenges

that shape its implementation? Under this main

question, sub-questions can help in addressing this

aim comprehensively:

a. Technical Feasibility: What types of affective

computing technologies have shown potential in

detecting and assessing anxiety disorders symptoms?

What evidence exists regarding their accuracy,

robustness, and usability?

b. Clinical Feasibility and Integration: To what

extent have these technologies been incorporated into

clinical pathways, and what specific use cases have

shown promise?

c. Sociological and Ethical Considerations: What

cultural considerations could influence the

widespread integration of AC in ADs?

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 flow diagram adapted for this

rapid literature review.

2.1 Search Strategy and Data Sources

This literature review sets various challenges given the

use of similar terminology from different fields within

different meanings. An example of this semantic

overlap relates to the keywords "emotion detection" or

"emotion recognition": while in psychology this refers

to the capability of individuals of understanding others’

emotions, in technology this refers to AC solutions

capable of finding emotional patterns in certain data

modalities. In order to overcome these challenges, a

bivalent research approach has been proposed and

implemented. This approach comprises two distinct

methods. The first is conducted through the databases'

native interfaces, while the second exploits certain

features of the free software "Publish or Perish 8"

(https://harzing.com/). The latter method utilises the

software's “search in the references” feature. The two

approaches were carried out using two distinct

databases to provide comprehensive coverage across

all academic disciplines: Google Scholar and PubMed.

An overview of the methodology and a quantification

of the results are presented in Fig. 1.

The prompt used within the native interfaces of

the aforementioned databases was adapted to their

respective features and constraints.

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

275

- in PubMed: (("affective computing" OR "emotion

recognition" OR "emotion detection"[Title/Abstract])

AND (*disorder*[Title/Abstract]))

- in Google Scholar: for title only: allintitle: "affective

computing" OR "emotion recognition" OR "emotion

detection" "*disorder*”. Where *disorder* was

substituted with the followings in different entries:

obsessive compulsive disorder, OCD, post-traumatic

disorder, PTSD, panic disorder, panic attack, social

anxiety, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder,

GAD.

The parallel search strategy based on Publish or

Perish focused on the term "affective computing"

within the text, including references, to ensure a

thorough exploration of relevant literature. The

search strategy involved filtering articles with titles

containing specific keywords related to anxiety

disorders (i.e. the aforementioned in *disorder*).

2.2 Screening and Selection

Of the 355 reports initially found combining the two

research approaches, 152 have been discarded as

duplicates. For the subsequent selection process,

exclusion criteria were established to ensure the

relevance and quality of the chosen papers.

Excluded papers included non-peer-reviewed

sources such as books, theses, and magazine articles

(n=8), as well as works in languages other than

English (n=2). Additionally, meta-analysis or

review papers (n=7), as well as papers focused on

non-pathological anxiety or on aspects other than

emotion recognition and detection through

technology (e.g. virtual reality implementation)

were omitted (n=31).

2.3 Results Overview

38 papers met the inclusion criteria. Of these two are

purely theoretical without involving

experimentation (Hinduja et al., 2024; Howard et

al., 2014), one was a pivot study (Cohn et al., 2018)

of another (Provenza et al., 2021), and another one

(Kathan et al., 2024) an integration study of a

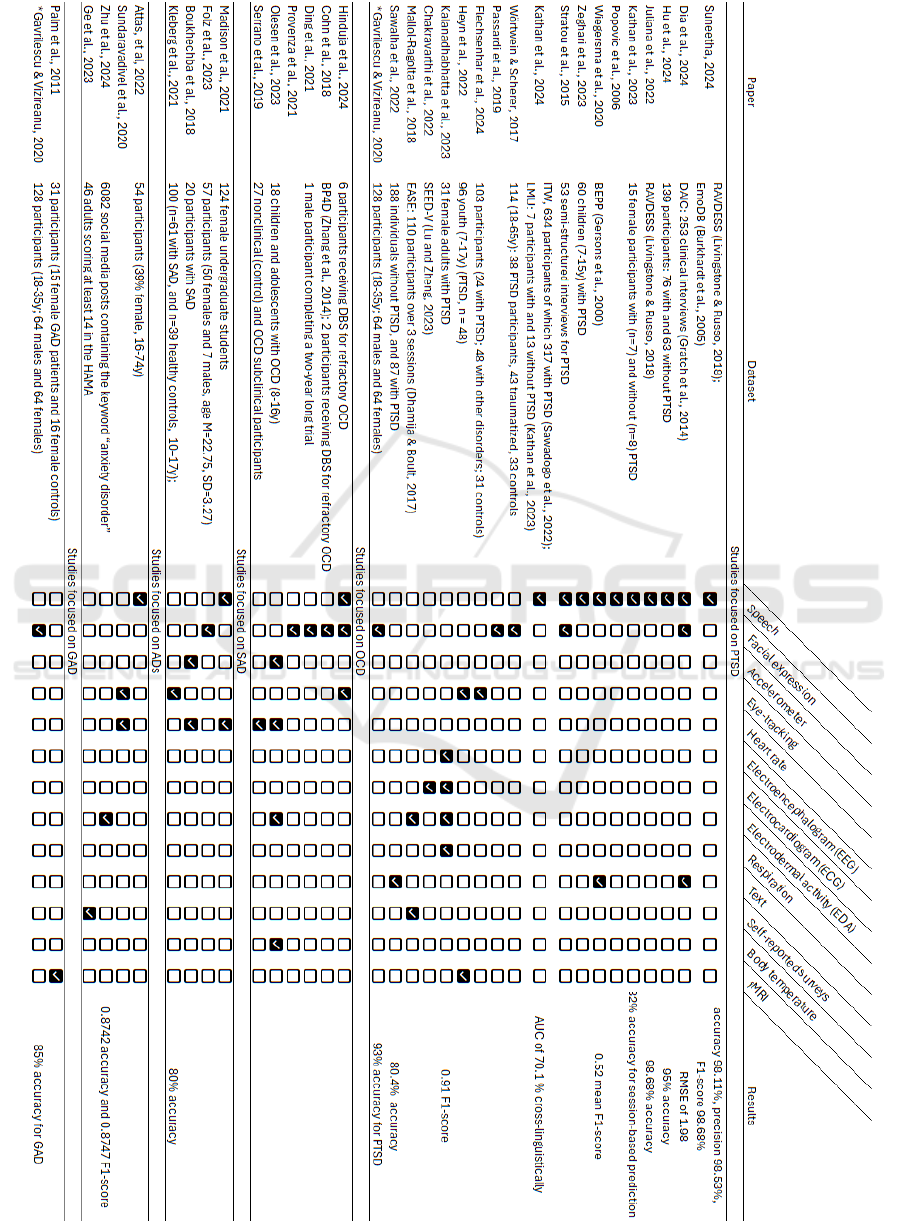

previous one (Kathan et al., 2023). In Fig. 2 has been

reported the distribution of papers over the years and

which sub-type of anxiety disorders they focus on.

The most evident insights from this stacked column

chart is that PTSD is the most studied sub-disorder

and that there is a consistent increasing research

effort in this field in the last seven years (data

updated to October 2024).

3 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

In this section the results of the literature review will

be contextualised within the three research questions

introduced in the methodology.

Figure 2: Annual distribution (up to October 2024*) and

classification by anxiety sub-disorders of the publications

included in this review.

3.1 Technical Feasibility of AC for ADs

By comparing the studies found in this review it is

important to consider the diversity among anxiety

sub-disorders, data modalities implemented, and

dataset used. These aspects are summarised in Tab. 1,

with a particular attention for the data used as this is

useful not only to evaluate the reliability of the

studies, but also to consider the mentioned datasets

for future research. Some of the studies, for instance,

utilized previous works or distinct datasets as

benchmarks (Attas et al., 2022) to assess the

generalization capabilities of ML algorithms

(Chappidi Suneetha, 2024), or to develop multimodal

approaches, which appear to outperform their

unimodal counterparts (Kalanadhabhatta et al., 2023).

Moreover, ML models (transformers above all)

require a huge quantity of data to be trained, leading

to the need of merging different datasets or taking

advantage of alternative methods, such as transfer

learning (Dia et al., 2024). However, not all the works

reviewed relied on ML, in fact a third of the studies

opted for pure statistical solutions, which, whenever

applicable, offer more straightforward and

explainable results.

The results declared by several studies, included

in Tab. 1, are promising for future in-wild or clinical

explorations. However, it is mandatory to also refer

to the dimension of the datasets used for testing them

as well as the nature of the data, given that real-case

scenario data are often noisier and more difficult to

manage. From a pragmatic perspective it’s also

important to consider the kind of implementation for

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

276

which each technology is suggested for, as different

requirements and characteristics might be prioritised.

Of the reviewed studies 43.3% referred to DEM,

56.7% to ADM emotion classifications. However, in

both cases there is not an absolute consistency in the

number or types of labels used. For example two

studies only included dominance in their ADM

emotion evaluations (Kathan et al., 2023; Serrano et

al., 2019), and one study referred to positive and

negative emotions (Zhu et al., 2024). This

heterogeneity is a further challenge for the comparison

of different ML approaches and for the implementation

of different datasets in the same work.

When studying emotions and emotional responses,

the first step faced is the need of triggering the target

emotions. Emotional elicitation methods varied, with

most studies employing clinical situations (e.g.

interviews, therapy, cognitive tasks), while some

altered environmental conditions (e.g. reproducing

natural sounds (Ge et al., 2023; Sundaravadivel et al.,

2020) or using virtual reality (VR) (Moussaoui et al.,

2007)) or utilized Ecological Momentary Assessments

(EMAs) in period of time ranging from 3 (Boukhechba

et al., 2018) to 8 weeks (Olesen et al., 2023). The next

step consists of the proper emotion detection. Emotion

labelling has been performed following three main

approaches: a) using standardized self-reported survey

to define emotion labels (e.g. Kruskal-Wallis test (Ge

et al., 2023), or "Positive and Negative Affect

Schedule" (Watson et al., 1988), combined with

"Somatic Arousal – Fear questionnaire" (NIH, 2024)

and "10-item Perceived Stress Scale" (Cohen et al.,

1983)); b) relaying on previously validated datasets

(e.g. RECOLA or RAVDESS); c) expert annotations

of subjects’ responses to stimuli (e.g. clinical

interviews); d) using already validated emotional-

related proxies ML models and/filters (e.g. General

Purpose Emotion Lexicon (GPEL) for text analysis

(Bandhakavi et al., 2017), GeMAPS from openSMILE

toolkit for speech analysis (Eyben et al., 2016)). Both

for emotion eliciting and labelling, using standardized

approaches not only reduces the workload required for

designing a new experiment, but also brings benefits in

terms of reproducibility and evaluation.

3.2 Clinical Integration and

Applications in Anxiety Pathways

Ten studies proposed innovations suitable for clinical

pathways (Cohn et al., 2018; Attas, 2022; Ding et al.,

2021; Flechsenhar et al., 2024; Hinduja et al., 2024;

Moussaoui et al., 2007; Olesen et al., 2023; Popovic

et al., 2006; Provenza et al., 2021; Wörtwein &

Scherer, 2017), while most of the works were more

oriented towards pure scientific exploration, such as

analysing alexithymia (i.e. the impairment of

recognition and description of one's own emotional

states) in ADs, or optimizing technological solutions

such as ML models in AC for ADs, or improving our

understanding of how people affected by ADs

experience emotions and which are the characteristic

differences that can help in detecting and monitoring

them. (Bakker et al., 2014) underlined the importance

of incorporating the dimension of Dominance to

achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the

emotional spectrum. Integrating Dominance poses a

challenge due to the scarcity of datasets that label this

dimension. Therefore, the development of more

datasets including the three scales would be greatly

valued for the research community (Verma & Tiwary,

2017). It is also been discussed that alterations in the

dominance motivation, dominant and subordinate

behaviour, and responsivity to perceptions of power

and subordination are linked to a broad range of

psychopathologies (Johnson et al., 2012).

Despite the consistent number of papers, there is

a lack of prior work on detecting PTSD in daily

activities, especially in non-military populations

(Kalanadhabhatta et al., 2023). It is reasonable to

assume that military organizations offer financial

support for PTSD research given its correlation with

combat experiences and provide easy environments

for participant recruitment, mitigating two major

research challenges. Hyperarousal is considered

symptomatic in PTSD during re-experiencing

traumatic memories (Fontana, 2022), and an altered

disgust perception is considered a relevant feature in

OCD (Serrano et al., 2019), hence they have been

explored for detection and monitoring using affective

computing solutions.

Moreover, not all the sub-disorders are equally

represented: PTSD accounted for 21 out of the 38

selected papers (55.26%), while other sub-types such

as OCD (n=6), SAD (n=5), generic ADs (n=4), and

GAD (n=2) were underrepresented. This underlines a

notable gap in the literature that might be filled by

transposing to different sub-disorders approaches

included in this review. 18 studies were based on data

collected ex-novo, instead of pre-built dataset (n=11).

This presented the researchers with the need to assess

the presence and eventually the gravity of the ADs in

their participants. The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(HAM-A) was used for evaluating broad ADs (Ge et

al., 2023), while specific tests were applied for the

sub-types, including versions for adult or paediatric

populations (on which 4 studies only where focused

(Heyn et al., 2022; Kleberg et al., 2021; Olesen et al.,

2023; Zeghari et al., 2023)), but also to verify the

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

277

Table 1: Data modalities used for emotion detection (the study marked with an * focuses on both PTSD and GAD).

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

278

presence of comorbidities (e.g. depression). Some

studies encountered challenges in recruiting male

participants, resulting in either female-only studies

(Kalanadhabhatta et al., 2023; Kathan et al., 2023) or

deliberate focus on females only (Madison et al.,

2021; Serrano et al., 2019).

3.3 Practical and Pragmatic Challenges

Gender and culture significantly influence our

perception and emotional responses, affecting how

mental health disorders are experienced and

manifested (Maner et al., 2008; Stratou et al., 2015).

In according to this assumption, gender-dependent

models outperformed gender-agnostic approaches in

PTSD, underscoring the importance of considering

gender in AC machine learning models for ADs

(Cohn et al., 2018). Some models trained on a

language (e.g. Zhu et al., 2024) might not generalize

that well when applied on other ones, as demonstrated

by (Kathan et al., 2024).

As we navigate the realm of emotions, one of the

most intimate aspects of human nature, it is

imperative to prioritize the privacy and security of the

frameworks proposed. However, apart from one

exception (i.e. Dia et al., 2024), none of the selected

papers gives substantial attention to the ethical

implications of detecting emotions from individuals

or the potential ramifications in future clinical

integrations. However, it is crucial to consider the

ethical dimensions surrounding emotion recognition

technologies, particularly in mental health contexts.

Cameras and microphones, commonly used for

emotion recognition, as confirmed by this review, are

perceived as non-invasive sensors. Yet, their ease of

data collection raises significant privacy concerns,

potentially infringing on individuals' privacy rights

without their consent or awareness. In contrast,

physiological approaches offer users greater control

over data acquisition and minimize the risk of

manipulation compared to facial expression analysis.

However, the deeper privacy implications of

understanding individuals' emotions highlight the

need for a cautious and ethical approach to prevent

misuse and protect individual freedoms (Bunn, 2012).

The sensitive nature of emotion understanding

underscores the importance of ethical considerations

to prevent potential misuse and safeguard privacy

rights. The EU AI Act, the first of its kind,

recognizing ethical emotion detection as a critical

task for AI, emphasizes the need for responsible

practices in this area (European Parliament, 2023).

Additionally, recognizing gender and cultural

differences in emotional expression and experience

(Butler et al., 2007), it is imperative to collect diverse

datasets to train and test AI models before

deployment, ensuring inclusivity and avoiding biases.

Moreover, studies involving individuals with

mental health conditions raise concerns about the

potential triggering of anxiety-related crises during

emotion elicitation tasks. While ethical approval is

obtained from institutional review boards, and

methodologies are often justified by their

resemblance to clinical practices such as exposure

therapy, further caution and attention to this matter

are warranted. Consulting with patients and

clinicians, ideally through a co-production approach,

would not only aid in developing more relevant

solutions but also ensure the design of more

comfortable experimental settings.

4 CHALLENGES AND FUTURE

DIRECTIONS

ML, and the Transformer architecture over all, has

demonstrated promising results in emotion detection

(Dia et al., 2024; Wagner et al., 2023), yet it demands

a substantial quantity of data, a notable limitation in

the affective computing field (Mustaqeem & Brahem,

Haddou, 2023). One potential solution, already

explored by some authors, is to apply transfer

learning, leveraging large datasets for a specific data

modality and fine-tuning the model for emotional

recognition tasks using smaller, specific datasets (e.g.

for ECG (Dentamaro et al., 2023)). Another avenue

to expand available datasets is the utilization of

synthetic data, which can train ML models before

being tested on natural data (Ive, 2022). This

approach also offers reduction of privacy concerns

related to potentially sensitive data, and the potential

to lessen bias by including rare cases that represent

realistic possibilities but may be challenging to source

from authentic data (Gonzales et al., 2023).

Most of the considered studies focus on one sub-

type of ADs exclusively: PTSD. Although this

approach effectively narrows the scope and ensures

adequate representation of subjects within the same

subtype, it may compromise differential diagnosis.

Specifically, it risks attributing certain patterns to a

subtype simply because they differ from non-

pathological cases, such as those in a control group or

data collected at different time points from the same

subject Chappidi (Kathan et al., 2023). While specific

emotion-eliciting conditions may contextualize

collected data, structuring studies to embrace a trans-

diagnostic approach could benefit pragmatic solution

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

279

development for clinical implementation. In this

regard, a review work comparing ECG-based

evaluations for different ADs sub-types, is

particularly relevant (Elgendi & Menon, 2019).

More explorative research is welcomed and

needed to fill the aforementioned gaps. However, it is

hoped that, works justifying their limited number of

recruited subjects as pilot studies, will be followed up

with extended research, as exemplified by various

works (Cohn et al., 2018; Provenza et al., 2021).

Failure to do so poses the risk of accumulating

hypothetical considerations that remain distant from

concrete integration in clinical practice.

Digital solutions in mental health are affected by a

significant usage drop-off rate (Nwosu et al., 2022).

There is a risk of developing solutions for longitudinal

data collection (e.g. in EMA) that fail due to user non-

adherence. One solution to this issue would be to

involve the public early on to incorporate their

perspectives, as well as clinicians, to understand how

to integrate patient preferences into scientifically

useful applications. Co-design, also known as co-

production, offers a valuable approach to mitigate

these issues (Esmail et al., 2015), and there are already

valuable examples of this approach for developing

mental health digital solutions (Thieme et al., 2023).

5 LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

This rapid literature review relies solely on two

datasets. Expanding the research to other datasets

(e.g. IEEE Xplore Digital Library, Prospero, Scopus,

etc.) may uncover papers not included in this analysis.

Moreover, a more systematic approach could be

adopted by following specific guidelines for literature

reviews, such as the Cochrane methods guidance

(Garritty et al., 2024; Klerings et al., 2023).

Another intriguing aspect worth considering is the

comparison between studies focused on an AC

approach (i.e. involving emotion recognition) versus

other feature extraction approaches. Is detecting

emotions genuinely valuable? Is it appreciated by

patients and clinicians as an understandable way to

report and interpret collected data, particularly in

longitudinal approaches?

From a technical standpoint, conducting a more

in-depth analysis and comparison regarding the pre-

processing techniques utilized in the reviewed studies

to prepare the data for emotional feature extraction

would be beneficial. This analysis could offer

valuable insights into optimizing the data preparation

process for future research endeavours in different

data modalities for affective computing.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The latest findings indicate that affective computing

(AC) holds significant potential to enhance current

clinical pathways in anxiety disorders (ADs). While

existing studies yield promising results, further

research is essential.

The main insights underlined by this review could

be summarised as follows:

- Some aspects are understudied, including gender

differences, paediatric populations, some sub-

disorders, and their differences.

- The most used data modalities are voice and facial

expressions, while multimodal approaches seem to

outperform unimodal ones.

- There is a lack of large, multimodal, and

standardised AC datasets for ADs to enable direct

comparisons between technical approaches and

account for the diversity of approaches in this field.

- Promising results have been demonstrated in

research and digital environments, but more in-the-

wild data collection and clinical validations are

needed.

By addressing these gaps through

interdisciplinary collaboration, AC can transition

from a promising research avenue to a valuable tool

in clinical practice for anxiety disorders.

REFERENCES

Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of Mental

Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014. (2014). NHS

England Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-

information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-

morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-

survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014

Anitha, C. S. (2022). A Survey Of Machine Learning

Techniques OnSpeech Based Emotion Recognition

And Post Traumatic Stress DisorderDetection.

NeuroQuantology, 20(14), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.

48047/nq.2022.20.14.NQ88010

Apablaza, J., & Cano, S. (2020). Affective Computing from

Digital Health: A literature review.

Attas, D., Kellett, S., & Blackmore, C. (2022). Automatic

Time-Continuous Prediction of Emotional Dimensions

During Guided Self Help for Anxiety Disorders. 35–39.

https://doi.org/10.6094/UNIFR/223814

Baker, C., & Kirk-Wade, E. (2024). Mental health statistics:

Prevalence, services and funding in England.

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-

briefings/sn06988/

Bakker, I., Van Der Voordt, T., Vink, P., & De Boon, J.

(2014). Pleasure, Arousal, Dominance: Mehrabian and

Russell revisited. Current Psychology, 33(3), 405–421.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9219-4

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

280

Bandhakavi, A., Wiratunga, N., Padmanabhan, D., &

Massie, S. (2017). Lexicon based feature extraction for

emotion text classification. Pattern Recognition Letters,

93, 133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2016.12.009

Berking, M., Poppe, C., Luhmann, M., Wupperman, P.,

Jaggi, V., & Seifritz, E. (2011). Emotion-regulation

skills and psychopathology: Is the ability to modify

emotions the pathway by which other emotion-

regulation skills affect mental health? Journal of

Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry.

Berking, M., & Wupperman, P. (2012). Emotion regulation

and mental health: Recent findings, current challenges,

and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry,

https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669

Boukhechba, M., Gong, J., Kowsari, K., Ameko, M. K.,

Fua, K., Chow, P. I., Huang, Y., Teachman, B. A., &

Barnes, L. E. (2018). Physiological changes over the

course of cognitive bias modification for social anxiety.

2018 IEEE EMBS International Conference on

Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI), 422–425.

https://doi.org/10.1109/BHI.2018.8333458

Bunn, G. C. (2012). The Truth Machine: A Social History

of the Lie Detector. JHU Press.

Butler, E. A., Lee, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion

regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of

emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7(1),

30–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.30

Bystritsky, A., Khalsa, S. S., Cameron, M. E., & Schiffman,

J. (2013). Current Diagnosis and Treatment of Anxiety

Disorders. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 38(1), 30–57.

Calvo, R. A., D’Mello, S., Gratch, J., Kappas, A., Calvo, R.

A., D’Mello, S., Gratch, J., & Kappas, A. (Eds.).

(2015). The Oxford Handbook of Affective Computing.

Oxford University Press.

Chappidi Suneetha, E. Al. (2024). Enhanced Speech

Emotion Recognition Using the Cognitive Emotion

Fusion Network for PTSD Detection with a Novel

Hybrid Approach. Journal of Electrical Systems, 19(4),

376–398. https://doi.org/10.52783/jes.644

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A

Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health

and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. https://doi.

org/10.2307/2136404

Cohn, J. F., Jeni, L. A., Onal Ertugrul, I., Malone, D., Okun,

M. S., Borton, D., & Goodman, W. K. (2018).

Automated Affect Detection in Deep Brain Stimulation

for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Pilot Study.

Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference

on Multimodal Interaction, 40–44.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3242969.3243023

De Witte, N. A. J., Joris, S., Van Assche, E., & Van Daele,

T. (2021). Technological and Digital Interventions for

Mental Health and Wellbeing: An Overview of

Systematic Reviews. Frontiers in Digital Health, 3.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2021.754337

Dentamaro, V., Impedovo, D., Moretti, L. A., & Pirlo, G.

(2023). An Approach using transformer architecture for

emotion recognition through Electrocardiogram

Signal(s).

Dia, M., Khodabandelou, G., & Othmani, A. (2024). Paying

attention to uncertainty: A stochastic multimodal

transformer for post-traumatic stress disorder detection

using video. Computer Methods and Programs in

Biomedicine, 257, 108439. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.cmpb.2024.108439

Ding, Y., Onal Ertugrul, I., Darzi, A., Provenza, N., Jeni, L.

A., Borton, D., Goodman, W., & Cohn, J. (2021).

Automated Detection of Optimal DBS Device Settings.

Companion Publication of the 2020 International

Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 354–356.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3395035.3425354

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Ellsworth, P. (1972). Emotion

in the human face: Guidelines for research and an

integration of findings (pp. xii, 191). Pergamon Press.

Elgendi, M., & Menon, C. (2019). Assessing Anxiety

Disorders Using Wearable Devices: Challenges and

Future Directions. Brain Sciences, 9(3), 50.

https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9030050

Esmail, L., Moore, E., & Rein, A. (2015). Evaluating

patient and stakeholder engagement in research:

Moving from theory to practice. Journal of

Comparative Effectiveness Research, 4(2), 133–145.

https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.14.79

European Parliament. (2023). Artificial intelligence act.

Eyben, F., Scherer, K. R., Schuller, B. W., Sundberg,

J., Andre, E., Busso, C., Devillers, L. Y., Epps, J.,

Laukka, P., Narayanan, S. S., & Truong, K. P. (2016).

The Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set

(GeMAPS) for Voice Research and Affective

Computing. IEEE Transactions on Affective

Computing, 7(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1109/

TAFFC.2015.2457417

Flechsenhar, A., Seitz, K. I., Bertsch, K., & Herpertz, S. C.

(2024). The association between psychopathology,

childhood trauma, and emotion processing.

Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and

Policy, 16(Suppl 1), S190–S203. https://doi.org/10.

1037/tra0001261

Fontana, A. (2022). A Model of Post-Traumatic Stress

Disorders and Dissociative Identity Disorder from the

perspective of Social Emotions. Medical Research

Archives, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v10i3.

2743

Garritty, C., Hamel, C., Trivella, M., Gartlehner, G.,

Nussbaumer-Streit, B., Devane, D., Kamel, C., Griebler,

U., & King, V. J. (2024). Updated recommendations for

the Cochrane rapid review methods guidance for rapid

reviews of effectiveness. BMJ, 384, e076335.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076335

Ge, Y., Xie, H., Su, M., & Gu, T. (2023). Effects of the

acoustic characteristics of natural sounds on perceived

tranquility, emotional valence and arousal in patients

with anxiety disorders. Applied Acoustics, 213, 109664.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2023.109664

Gonzales, A., Guruswamy, G., & Smith, S. R. (2023).

Synthetic data in health care: A narrative review. PLOS

Digital Health, 2(1), e0000082. https://doi.org/10.

1371/journal.pdig.0000082

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

281

Greenberg, L. S., & Safran, J. D. (1989). Emotion in

psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 44(1), 19–29.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.1.19

Greenberg, L. S., & Safran, J. D. (1990). Chapter 3-

emotional-change process in psychotherapy. In R.

Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion,

Psychopathology, and Psychotherapy (pp. 59–85).

Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-

558705-1.50009-9

Hattingh, C. J., Ipser, J., Tromp, S., Syal, S., Lochner, C.,

Brooks, S. J., & Stein, D. J. (2013). Functional

magnetic resonance imaging during emotion

recognition in social anxiety disorder: An activation

likelihood meta-analysis. Frontiers in Human

Neuroscience, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.

2012.00347

Heyn, S. A., Schmit, C., Keding, T. J., Wolf, R., &

Herringa, R. J. (2022). Neurobehavioral correlates of

impaired emotion recognition in pediatric PTSD.

Development and Psychopathology, 34(3), 946–956.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001704

Hinduja, S., Darzi, A., Ertugrul, I. O., Provenza, N., Gadot,

R., Storch, E., Sheth, S., Goodman, W., & Cohn, J.

(2024). Multimodal prediction of obsessive-

compulsive disorder, comorbid depression, and energy

of deep brain stimulation. https://doi.org/10.

36227/techrxiv.23256119.v2

Howard, N., Jehel, L., & Arnal, R. (2014). Towards a

differential diagnostic of PTSD using cognitive

computing methods. 2014 IEEE 13th International

Conference on Cognitive Informatics and Cognitive

Computing, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCI-

CC.2014.6921435

Hyer, L., Woods, M. G., & Boudewyns, P. A. (1991). PTSD

and alexithymia: Importance of emotional clarification

in treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research,

Practice, Training, 28(1), 129–139. https://doi.org/10

.1037/0033-3204.28.1.129

Ive, J. (2022). Leveraging the potential of synthetic text for

AI in mental healthcare. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4,

1010202. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.1010202

Johnson, S. L., Leedom, L. J., & Muhtadie, L. (2012). The

Dominance Behavioral System and Psychopathology:

Evidence from Self-Report, Observational, and

Biological Studies. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4),

692–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027503

Kalanadhabhatta, M., Roy, S., Grant, T., Salekin, A.,

Rahman, T., & Bergen-Cico, D. (2023). Detecting

PTSD Using Neural and Physiological Signals:

Recommendations from a Pilot Study. 2023 11th

International Conference on Affective Computing and

Intelligent Interaction (ACII), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.

1109/ACII59096.2023.10388200

Kathan, A., Bürger, M., Triantafyllopoulos, A., Milkus, S.,

Hohmann, J., Muderlak, P., Schottdorf, J., Musil, R.,

Schuller, B., & Amiriparian, S. (2024). Real-world

PTSD Recognition: A Cross-corpus and Cross-

linguistic Evaluation. Interspeech 2024, 487–491.

https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2024-493

Kathan, A., Triantafyllopoulos, A., Amiriparian, S.,

Milkus, S., Gebhard, A., Hohmann, J., Muderlak, P.,

Schottdorf, J., Schuller, B. W., & Musil, R. (2023). The

effect of clinical intervention on the speech of

individuals with PTSD: Features and recognition

performances. INTERSPEECH 2023, 4139–4143.

https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2023-1668

Kleberg, J. L., Löwenberg, E. B., Lau, J. Y. F., Serlachius,

E., & Högström, J. (2021). Restricted Visual Scanpaths

During Emotion Recognition in Childhood Social

Anxiety Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.658171

Klerings, I., Robalino, S., Booth, A., Escobar-Liquitay, C.

M., Sommer, I., Gartlehner, G., Devane, D., &

Waffenschmidt, S. (2023). Rapid reviews methods

series: Guidance on literature search. BMJ Evidence-

Based Medicine, 28(6), 412–417. https://doi.org/10.

1136/bmjebm-2022-112079

Madison, A., Vasey, M., Emery, C. F., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J.

K. (2021). Social anxiety symptoms, heart rate

variability, and vocal emotion recognition in women:

Evidence for parasympathetically-mediated positivity

bias. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(3), 243–257.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1839733

Maner, J. K., Miller, S. L., Schmidt, N. B., & Eckel, L. A.

(2008). Submitting to Defeat: Social Anxiety,

Dominance Threat, and Decrements in Testosterone.

Psychological Science, 19(8), 764–768. https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02154.x

Mehrabian, A. (1997). Comparison of the PAD and

PANAS as models for describing emotions and for

differentiating anxiety from depression. Journal of

Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 19(4),

331–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02229025

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to

environmental psychology (pp. xii, 266). The MIT

Press.

Michelutti, A. D., & D. Relić. (2022). Health workforce

shortage – doing the right things or doing things right?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9086

817/Picard, R. W. (1997). Affective computing. MIT

Press.

Moussaoui, A., Pruski, A., & Brahim, C. (2007). Emotion

regulation for social phobia treatment using virtual

reality.

Mustaqeem, A. O., & B. Brahem, Y. Haddou. (2023).

Machine-Learning-Based Approaches for Post-

Traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis Using Video and

EEG Sensors: A Review | IEEE Journals & Magazine |

IEEE Xplore. 24135–24151. https://doi.org/10.11

09/JSEN.2023.3312172

NIH. (2024). NIH Toolbox Fear/Somatic Arousal FF

Ages 18+ v3.0 [Eeg]. HealthMeasures. https://www.

healthmeasures.net/index.php

Nwosu, A., Boardman, S., Husain, M. M., & Doraiswamy,

P. M. (2022). Digital therapeutics for mental health: Is

attrition the Achilles heel? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13,

900615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.900615

Olesen, K. V., Lønfeldt, N. N., Das, S., Pagsberg, A. K., &

Clemmensen, L. K. H. (2023). Predicting Obsessive-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

282

Compulsive Disorder Events in Children and

Adolescents in the Wild Using a Wearable Biosensor

(Wrist Angel): Protocol for the Analysis Plan of a

Nonrandomized Pilot Study. JMIR Research Protocols,

12(1), e48571. https://doi.org/10.2196/48571

Popovic, S., Slamic, M., & Cosic, K. (2006). Scenario Self-

Adaptation in VR Exposure Therapy for PTSD

Provenza, N. R., Sheth, S. A., Dastin-van Rijn, E. M.,

Mathura, R. K., Ding, Y., Vogt, G. S., Avendano-

Ortega, M., Ramakrishnan, N., Peled, N., Gelin, L. F.

F., Xing, D., Jeni, L. A., Ertugrul, I. O., Barrios-

Anderson, A., Matteson, E., Wiese, A. D., Xu, J.,

Viswanathan, A., Harrison, M. T., … Borton, D. A.

(2021). Long-term ecological assessment of

intracranial electrophysiology synchronized to

behavioral markers in obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Nature Medicine, 27(12), 2154–2164. https://doi.org/

10.1038/s41591-021-01550-z

Serrano, M. Á., Rosell-Clari, V., & García-Soriano, G.

(2019). The Role of Perceived Control in the

Psychophysiological Responses to Disgust of

Subclinical OCD Women. Sensors, 19(19), Article 19.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s19194180

Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J., Miller, J. G.,

Hartman, T. K., Levita, L., Mason, L., Martinez, A. P.,

McKay, R., Stocks, T. V. A., Bennett, K. M., Hyland,

P., Karatzias, T., & Bentall, R. P. (2020). Anxiety,

depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related

anxiety in the UK general population during the

COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open, 6(6), e125.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.109

Slade, T., Johnston, A., Oakley Browne, M. A., Andrews,

G., & Whiteford, H. (2009). 2007 National Survey of

Mental Health and Wellbeing: Methods and Key

Findings. Australian & New Zealand Journal of

Psychiatry, 43(7), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00048670902970882

Stein, D. J., Costa, D. L. C., Lochner, C., Miguel, E. C.,

Reddy, Y. C. J., Shavitt, R. G., van den Heuvel, O. A.,

& Simpson, H. B. (2019). Obsessive–compulsive

disorder. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 5(1), 52.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0102-3

Stratou, G., Scherer, S., Gratch, J., & Morency, L.-P.

(2015). Automatic nonverbal behavior indicators of

depression and PTSD: The effect of gender. Journal on

Multimodal User Interfaces, 9(1), 17–29.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12193-014-0161-4

Sundaravadivel, P., Goyal, V., & Tamil, L. (2020). i-RISE:

An IoT-based Semi-Immersive Affective monitoring

framework for Anxiety Disorders. 2020 IEEE

International Conference on Consumer Electronics

(ICCE), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCE46568.2020.

9043156

Suneetha, C., & Anitha, R. (2024). Advancements in

Speech-Based Emotion Recognition and PTSD

Detection through Machine and Deep Learning

Techniques: A Comprehensive Survey. International

Journal of Electronics and Communication

Engineering, https://doi.org/10.14445/23488549/

IJECE-V11I5P121

Thieme, A., Hanratty, M., Lyons, M., Palacios, J., Marques,

R. F., Morrison, C., & Doherty, G. (2023). Designing

Human-centered AI for Mental Health: Developing

Clinically Relevant Applications for Online CBT

Treatment. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human

Interaction, 30(2), 27:1-27:50.

Ugbolue, U. C., Duclos, M., Urzeala, C., Berthon, M.,

Kulik, K., Bota, A., Thivel, D., Bagheri, R., Gu, Y.,

Baker, J. S., Andant, N., Pereira, B., Rouffiac, K.,

Clinchamps, M., Dutheil, F., & on behalf of the

COVISTRESS Network. (2020). An Assessment of the

Novel COVISTRESS Questionnaire: COVID-19

Impact on Physical Activity, Sedentary Action and

Psychological Emotion. Journal of Clinical Medicine,

9(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103352

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2024).

Anxiety Disorders. National Institute of Mental

Health https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-

disorders

Verma, G., & Tiwary, U. S. (2017). Affect Representation

and Recognition in 3D Continuous Valence-Arousal-

Dominance Space. Multimedia Tools and Applications,

76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-015-3119-y

Wagner, J., Triantafyllopoulos, A., Wierstorf, H., Schmitt,

M., Burkhardt, F., Eyben, F., & Schuller, B. W. (2023).

Dawn of the Transformer Era in Speech Emotion

Recognition: Closing the Valence Gap. IEEE

Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine

Intelligence, 45(9), 10745–10759. IEEE Transactions

on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3263585

Walz, L. C., Nauta, M. H., & aan het Rot, M. (2014).

Experience sampling and ecological momentary

assessment for studying the daily lives of patients with

anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Journal of

Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 925–937. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.022

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988).

Development and validation of brief measures of positive

and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wörtwein, T., & Scherer, S. (2017). What really matters—

An information gain analysis of questions and reactions

in automated PTSD screenings. 2017 Seventh

International Conference on Affective Computing and

Intelligent Interaction (ACII), 15–20. https://doi.

org/10.1109/ACII.2017.8273573

Yazdani, A., Skodras, E., Fakotakis, N., & Ebrahimi, T.

(2013). Multimedia content analysis for emotional

characterization of music video clips. EURASIP

Journal on Image and Video Processing, 2013(1), 26.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-5281-2013-26

Yehuda, R., Hoge, C. W., McFarlane, A. C., Vermetten, E.,

Lanius, R. A., Nievergelt, C. M., Hobfoll, S. E.,

Koenen, K. C., Neylan, T. C., & Hyman, S. E. (2015).

Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Reviews Disease

Primers, 1(1), 15057. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.

2015.57

Affective Computing in Anxiety Disorders: A Rapid Literature Review of Emotion Recognition Applications

283

Zeghari, R., Gindt, M., König, A., Nachon, O., Lindsay, H.,

Robert, P., Fernandez, A., & Askenazy, F. (2023).

Study protocol: How does parental stress measured by

clinical scales and voice acoustic stress markers predict

children’s response to PTSD trauma-focused therapies?

BMJ Open, 13(5), e068026. https://doi.org/10.1136/

bmjopen-2022-068026

Zhu, J., Zhang, Z., Guo, Z., & Li, Z. (2024). Sentiment

Classification of Anxiety-Related Texts in Social

Media via Fuzing Linguistic and Semantic Features.

IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems,

11(5), 6819–6829. IEEE Transactions on

Computational Social Systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/

TCSS.2024.3410391.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

284