Deep Learning-Based Classification of Stress in Sows Using Facial Images

Syed U. Yunas

1

, Ajmal Shahbaz

1

, Emma M. Baxter

2

, Marianne Farish

2

, Kenneth M. D. Rutherford

2

,

Mark F. Hansen

1

, Melvyn L. Smith

1

and Lyndon N. Smith

1

1

Centre for Machine Vision, University of the West of England (UWE), Bristol, U.K.

2

Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC), Edinburgh, U.K.

{syed.yunas, ajmal.shahbaz}@uwe.ac.uk, {emma.baxter, marianne.farish, kenny.rutherford}@sruc.ac.uk,

Keywords:

Sow Stress Classification, YOLO Model, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Deep Learning in

Agriculture, Animal Welfare Monitoring, Stress Detection from Facial Images.

Abstract:

Stress in pigs is a significant factor contributing to poor health, increased antimicrobial usage, and the sub-

sequent risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which poses a major challenge for the global pig farming

industry. In this paper, we propose using deep learning (DL) methods to classify stress levels in sows based on

facial features captured from images. Early identification of stress can enable targeted interventions, poten-

tially reducing health risks and mitigating AMR concerns. Our approach utilizes convolutional neural network

(CNN) models, specifically YOLO8l-cls, to classify the stress levels of sows (pregnant pigs) into low-stressed

and high-stressed categories. Experimental results demonstrate that YOLO8l-cls outperforms other classifi-

cation methods, with an overall F1-score of 0.74, Cohen’s Kappa of 0.63, and MCC of 0.60. This highlights

the model’s effectiveness in accurately identifying stress levels and its potential as a practical tool for stress

management in pig farming, with benefits for animal welfare, the farming industry, and broader efforts to

minimize AMR risk.

1 INTRODUCTION

Modern livestock production demands a keen focus

on animal well-being, driven not only by ethical con-

siderations but also by its significant impact on fac-

tors such as animal health, productivity, and product

quality (Manteca and Alonso, 2000). Stress in pigs is

a major concern as chronic stress weakens their im-

mune system, making them more susceptible to in-

fections (Bartolom

´

e et al., 2004). This, in turn, fu-

els the overuse of antibiotics for treatment and pre-

vention, a significant contributor to the global threat

of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) (Arjun et al.,

2020). There is also potential for transgenerational

harm when mothers experience stress during preg-

nancy that can affect perinatal programming via epi-

genetic mechanisms, thus having significant impli-

cations for offspring development (Weinstock, 2008;

Ruijven and Oliehoek, 2017).

Early detection of stress in pigs is therefore

paramount for effective intervention. Traditional

methods, such as manual behavioural observation or

invasive physiological sampling, offer limited solu-

tions. They are time-consuming, expensive, and, in

the case of invasive physiological sampling, could

cause further distress to the animals (Wechsler, 2000),

(Broom, 2011). The development of a non-invasive

automated approach for objectively identifying ani-

mals susceptible to stress might ultimately allow se-

lection of pigs better equipped to cope with health and

environmental challenges.

Advancements in image and video analysis pow-

ered by deep learning, particularly the use of Convo-

lutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for extracting ro-

bust visual features, have revolutionized the study of

animal behaviour (Alpaydin et al., 2020). CNNs have

shown promising results in detecting stress among

different livestock species, including pigs, cows,

poultry, and fish, through the identification of facial

expressions or body language cues exhibited by these

animals (Wang et al., 2020b; Yang et al., 2020; Liu

et al., 2020; Arriaga et al., 2021).

Our study builds upon the prior work by re-

searchers (Hansen et al., 2021), which developed a

CNN-based model to detect stress in young female

pigs (gilts) within a controlled social defeat experi-

mental setup, achieving over 90% accuracy in classi-

fying gilts as stressed or not stressed. In contrast, the

390

Yunas, S. U., Shahbaz, A., Baxter, E. M., Farish, M., Rutherford, K. M. D., Hansen, M. F., Smith, M. L. and Smith, L. N.

Deep Learning-Based Classification of Stress in Sows Using Facial Images.

DOI: 10.5220/0013327900003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 390-396

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

(a) Recording sows: Four of the six

pregnant sows.

(b) Image cropping to exclude occlu-

sions from metal pen bars.

(c) Sow segmentation performed using

Mask-RCNN.

Figure 1: Experimental setup and data pre-processing of sow images.

current study extends this application to real-world,

routine farming conditions, specifically within dry

sow houses where pregnant sows are monitored un-

der standard farming practices. Unlike the model

developed by Hansen et al., which performed a bi-

nary classification of stressed versus non-stressed an-

imals, our study offers a more nuanced approach by

categorizing stress levels into Low-Stressed (LS) and

High-Stressed (HS) groups. This distinction pro-

vides a deeper understanding of stress levels in sows,

enabling a more detailed assessment of their well-

being in typical farming environments. We employed

and evaluated two advanced deep learning models—a

fine-tuned (FT) version of the original model used

by Hansen et al. and the YOLO8l-cls model (Ultra-

lytics, 2024)—to enhance classification performance

and ensure robustness across diverse stress indicators

and scenarios encountered in routine farming. These

modifications aim to not only demonstrate the scala-

bility of deep learning-based stress detection but also

adapt the methodology to better align with the practi-

cal needs of commercial pig farming, thereby advanc-

ing the utility and applicability of automated stress

monitoring systems in real-world settings.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section II

discusses the experimental setup, including the hard-

ware, dataset, and training process. Section III pro-

vides an overview of the original, FT, and YOLO8

models, including performance metrics used to evalu-

ate these models. Section IV presents the results and

discusses their implications. Finally, Section V con-

cludes the paper.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

2.1 Hardware

Video footage was captured on-farm at SRUC’s Pig

Research Centre, with all experiments reviewed and

approved by SRUC’s Ethical Review Board (AE14-

2022). The setup placed cameras within the dry sow

house, where sows are housed in individual straw

pens with feed stalls. To optimize video recording ef-

ficiency, each camera employed motion detection, au-

tomatically activating to capture high-resolution im-

ages (1920x1080 pixels) at 30 frames per second

when sows entered the feeding areas. Preventative

measures, such as mounting camera brackets outside

pen stalls, minimized the risk of animal interference

with equipment, ensuring both safety and ideal condi-

tions for the subjects.

Stress indicators in sows are often visible through

subtle changes in facial cues—such as the ears, eyes,

cheeks, and snout (Wang et al., 2020a). To reliably

capture these features, the cameras were positioned

at the end of each feed stall as shown in figure 1a,

ensuring the complete face, including eyes and nose,

were visible in each image. During pre-processing,

images were refined to focus primarily on the face,

although sometimes the sow’s body or legs were also

captured due to their proximity to the camera. This

approach was intended to enhance consistency in an-

alyzing facial stress markers while minimizing inter-

ference from other body parts.

2.2 Dataset

A dataset of 900 images was captured from six sows

on day 70 of their gestation. Modifications and fine-

tuning were applied to this dataset as described be-

low. Stress susceptibility, provided by SRUC as

ground truth data, was determined based on each

sow’s social rank and vulnerability to stress during

food competition, following the methodology out-

lined by (Dwyer et al., 2000). This was further

validated through behavioral observations (Janssens

et al., 1995) and cortisol measurements from saliva

samples (Jong et al., 1998), which classified the ani-

mals into low-stress (LS) and high-stress (HS) groups.

Deep Learning-Based Classification of Stress in Sows Using Facial Images

391

Figure 2: Architecture of the Fine-tuned (FT) model.

To ensure consistency in stress susceptibility cate-

gories, the ground truth data was verified through

multiple behavioral observations and controlled mea-

surements. This expert-labeled data served as the

foundation for training and validating our model, en-

suring that its classifications accurately reflected gen-

uine stress markers rather than individual differences

between animals.

Prior to model testing and training, all images

were cropped to exclude any occlusions from metal

pen bars, and a Mask-RCNN (He et al., 2017) was

employed for background segmentation, as shown in

figure 1b and 1c respectively. This approach ensured

that each image contained only the essential facial

features for analysis, improving the model’s focus on

relevant stress indicators.

2.3 Training Process

The dataset images were trained against ground truth

labels using a Windows 11 PC with a Core i9 proces-

sor running at 3 GHz, 32 GB of RAM, and an Nvidia

RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. The DL

models were implemented using the PyTorch library,

version 2.1.1 (Paszke et al., 2019). The training pro-

cess involved 1,000 epochs with a batch size of 32, a

learning rate of 0.0001, and utilizing the Adam opti-

mizer.

3 MODEL OVERVIEW

In this section, we outline the architectures of the

models employed in this study:

3.1 Original and Fine-Tuned (FT)

Models

The original model (Hansen et al., 2021) consists of

six ReLU-activated convolutional layers, five dropout

layers, three max-pooling layers, and two fully con-

nected layers. A sigmoid function is applied to deter-

mine the probability of a sow being stressed, with a

threshold (typically above 0.8) used to classify stress

presence.

In our study, the original model was fine-tuned on

the new dataset to better represent stress features as

observed on the farm as either low-stressed (LS) or

high-stressed (HS). While the original model was de-

signed to classify stressed (positive class) vs. non-

stressed (negative class), this study focuses on quan-

tifying stress levels into LS and HS categories. To

accommodate this, the final layer of the network was

modified to produce two output values, as illustrated

in figure 2. This adjustment removes the need for

thresholding the output, enabling direct classification

of stress levels.

3.2 YOLO8 Model

YOLO (You Only Look Once) is a versatile deep

learning framework widely used for various computer

vision tasks such as detection, segmentation, classifi-

cation, and pose estimation. Its architecture processes

an image by dividing it into a grid, predicting bound-

ing boxes, object confidence scores, and class proba-

bilities simultaneously. By applying Non-Maximum

Suppression (NMS) to eliminate overlapping detec-

tions, YOLO efficiently delivers accurate predictions

in real-time.

In this study, we utilize YOLO8l-cls (Ultralytics,

2024), a classification-specific variant of YOLO8, to

predict stress levels in sows from facial images. This

model was chosen for its strong performance in image

classification, making it well-suited for use as a stress

classifier. It was also selected to compare its stress

classification capabilities against both the original and

fine-tuned (FT) models.

3.3 Performance Metrics

Precision, Recall, and F1-Score are essential metrics

in classification tasks, crucial for assessing DL mod-

els’ performance. Precision, representing the ratio of

true positive predictions to the total positive predic-

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

392

Table 1: Cross-validation Results for Sow Stress Classification with Original, Fine-tuned (FT), and YOLO8l-cls Models.

Class Original Model FT Model YOLO8l-cls Model

(Train: 0 fold, Test: 3-fold) (Train: 2-fold, Test: 1-fold) (Train: 2-fold, Test: 1-fold)

Precision Recall F1-Score MCC Kappa Precision Recall F1-Score MCC Kappa Precision Recall F1-Score MCC Kappa

All 0.36 0.44 0.40 -0.12 -0.05 0.71 0.70 0.71 0.50 0.52 0.74 0.74 0.74 0.60 0.63

Low-Stressed (LS) 0.26 0.07 0.11 -0.20 -0.10 0.66 0.83 0.74 0.52 0.54 0.73 0.78 0.75 0.63 0.65

High-Stressed (HS) 0.46 0.81 0.59 0.02 0.00 0.77 0.57 0.66 0.48 0.50 0.76 0.51 0.61 0.55 0.56

tions made by the model, is expressed mathematically

as:

Precision =

True Positives

True Positives + False Positives

(1)

It indicates the proportion of correctly predicted

positive instances out of all instances predicted as

positive. Higher precision values suggest fewer false

positive predictions, reflecting the model’s ability to

avoid misclassification. Recall, also known as sen-

sitivity or true positive rate, measures the proportion

of actual positive instances correctly identified by the

model, calculated as:

Recall =

True Positives

True Positives + False Negatives

(2)

Higher recall values indicate the model’s effec-

tiveness in capturing most positive instances while

minimizing false negative predictions. The F1-score,

which is the harmonic mean of precision and recall,

provides a single metric that balances both concerns,

calculated as:

F1-Score = 2 ·

Precision · Recall

Precision + Recall

(3)

A higher F1-score indicates a good balance be-

tween precision and recall, offering a more compre-

hensive measure of the model’s performance.

In addition to precision, recall, and F1-score, we

also calculate the Matthews Correlation Coefficient

(MCC) and Cohen’s Kappa to provide a more com-

prehensive evaluation of the models’ performance.

These metrics help account for class imbalance and

offer insights into the models’ classification reliabil-

ity.

The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC)

is a robust metric for binary classification, especially

with imbalanced datasets. It is defined as:

MCC =

T P · T N − FP · FN

p

(T P + FP)(T P + FN)(T N + FP)(T N + FN)

(4)

where T P, T N, FP, and FN represent true pos-

itives, true negatives, false positives, and false nega-

tives, respectively. MCC values range from -1 (total

disagreement) to +1 (perfect prediction), with 0 indi-

cating no better performance than random chance.

The Cohen’s Kappa (κ) statistic measures the

agreement between predicted and actual classifica-

tions, adjusting for chance agreement:

κ =

p

o

− p

e

1 − p

e

(5)

where p

o

is the observed agreement, and p

e

is

the expected agreement by chance. Cohen’s Kappa

ranges from -1 (no agreement) to +1 (perfect agree-

ment).

These metrics are computed for each

model—Original, Fine-Tuned (FT), and YOLO8l-

cls—on both Low-Stressed (LS) and High-Stressed

(HS) classes. Results are detailed in Table 1 for

comparative evaluation.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 provides an overview of the performance met-

rics obtained from the cross-validation experiments

for sow stress classification. It details these met-

rics for each model—Original, Fine-tuned (FT), and

YOLO8l-cls—across the stress classes: Low-Stressed

(LS) and High-Stressed (HS). The table includes ad-

ditional metrics such as Matthews Correlation Coef-

ficient (MCC) and Cohen’s Kappa, providing a more

comprehensive evaluation of model performance.

Our dataset consists of 900 images from six sows

(three LS and three HS). These images are divided

into three folds, with 150 carefully selected images

from each sow, ensuring that each fold contains data

from one LS and one HS sow. The original model,

pretrained on the dataset used in (Hansen et al., 2021),

was tested on all three folds to evaluate its generaliza-

tion capabilities across the entire dataset. In contrast,

the fine-tuned (FT) and YOLO8l models were fine-

tuned on two folds and tested on the remaining fold

to assess their performance after transfer learning on

a subset of the data. This approach allows for a more

targeted evaluation of the models’ ability to adapt and

improve performance on specific stress indicators in

the dry sow house environment.

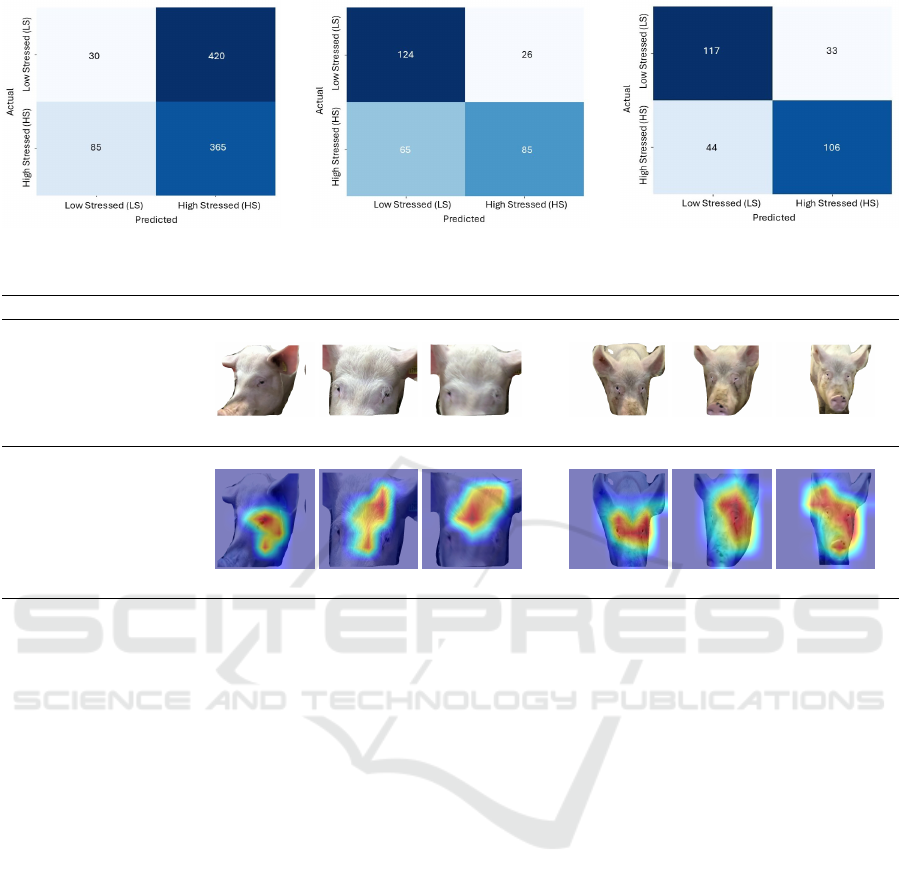

Figure 3 presents the confusion matrices for the

three models. The original model, shown in Figure

3a, struggles to classify LS sows accurately, misclas-

sifying 420 out of 450 LS sows as HS. This poor per-

Deep Learning-Based Classification of Stress in Sows Using Facial Images

393

(a) Original model. (b) FT model. (c) YOLO8l-cls model.

Figure 3: Results for Sow Stress Classification with Original, Fine-tuned (FT), and YOLO8l-cls Models.

Low-stressed (LS) High-stressed (HS)

Segmented Images

Grad-CAM Images

Figure 4: Grad-CAM visualizations of Low-Stressed (LS) and High-Stressed (HS) category sows using YOLO8l-cls model

with segmented input images.

formance is reflected in Table 1, where LS class met-

rics are low (Precision: 0.26, Recall: 0.07, F1-Score:

0.11). The Cohen’s Kappa of -0.10 and MCC of -0.20

further indicate weak agreement between predictions

and ground truth, suggesting a significant bias toward

the HS class.

The FT model, shown in Figure 3b, improves sig-

nificantly, classifying 124 out of 150 LS sows cor-

rectly. This improvement is reflected in the increased

precision (0.66), recall (0.83), and F1-Score (0.74) for

the LS class. The MCC and Kappa values of 0.52 and

0.54, respectively, also indicate a more balanced clas-

sification performance.

The YOLO8l-cls model, shown in Figure 3c,

demonstrates the best overall performance, achieving

a balanced classification across stress classes. It cor-

rectly identifies 117 out of 150 LS sows and 106 out

of 150 HS sows. The performance metrics are the

highest among the models tested, with LS precision,

recall, and F1-score of 0.73, 0.78, and 0.75, respec-

tively, and HS values of 0.76, 0.51, and 0.61. MCC

and Kappa values of 0.60 and 0.63 further support the

model’s reliability in predicting both stress categories

more accurately.

The inclusion of MCC and Cohen’s Kappa pro-

vides deeper insights into the models’ abilities to bal-

ance precision and recall across classes. MCC val-

ues near zero or negative indicate poor agreement

with ground truth, as seen in the original model’s per-

formance. The FT and YOLO8l-cls models, how-

ever, show positive MCC and Kappa values, reflecting

better agreement and a reduced bias between stress

classes.

Overall, the YOLO8l-cls model outperforms both

the original and FT models, achieving the highest F1-

Score (0.74) and the strongest Kappa (0.63). The

Grad-CAM visualizations in Figure 4 further confirm

the model’s effectiveness in identifying stress-related

regions in sow faces, highlighting key regions around

the eyes and forehead. This comprehensive analysis

emphasizes the importance of incorporating metrics

like MCC and Cohen’s Kappa in model evaluations

for more accurate and balanced performance assess-

ments.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the use of deep learning (DL)

models, particularly the YOLO8l-cls model, to clas-

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

394

sify stress levels in sows based on facial features in

a realistic farming environment, aiming to improve

animal welfare and reduce antimicrobial resistance

(AMR) risks in pig farming. The results showed

that the original pretrained model struggled to identify

low-stressed (LS) sows in a real-world scenario due to

its inability to capture subtle stress indicators, while

fine-tuning improved performance. The YOLO8l-cls

model exhibited the highest overall performance, with

an F1-score of 0.74, Cohen’s Kappa of 0.63, and

MCC of 0.60, indicating stronger agreement and bet-

ter generalization across both LS and high-stressed

(HS) categories. Its ability to balance precision and

recall and accurately identify subtle stress markers in

the facial regions underscores its potential.

These findings highlight YOLO8l-cls as a practi-

cal tool for real-time monitoring of sow stress, en-

abling early intervention and improving health man-

agement in farming environments. The model’s abil-

ity to detect stress markers, particularly in facial re-

gions, demonstrates its relevance for enhancing an-

imal welfare and addressing AMR concerns. How-

ever, the relatively small number of sows in this study

limits the model’s generalizability. Future work will

focus on expanding the dataset, incorporating more

diverse stress conditions, and testing the model on

cross-generational data, including both parents and

offspring, to explore the potential heritability of stress

markers. Further research will also assess the model’s

scalability in larger farming environments to validate

its reliability and applicability across different setups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the finan-

cial support provided by the Joint Programming Ini-

tiative on Antimi-crobial Resistance (JPIAMR) for

the FARM-CARE project, ‘FARM interventions to

Control Antimicrobial ResistancE - Full Stage’ (ID:

7429446), and the Medical Research Council (MRC)

for funding the UK part of the project (MRC re-

search grant number: MR/W031264/1). This project

is part of a collaboration between the University of

the West of England, Scotland’s Rural College, Uni-

versity of Copenhagen, Teagasc, University Hospital

Bonn, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), and Porkcolombia

Association.

REFERENCES

Alpaydin, K., Ucar, Y. S., and Devrim, M. E. (2020). Deep

learning-based approaches for animal behavior analy-

sis: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agricul-

ture, 170.

Arjun, G. S. R. D. D., Mary, S. A., and Daniel, M. K. S. A.

(2020). Antibiotic use in agriculture and its impact on

antimicrobial resistance. Environmental Science and

Pollution Research, 27(6):6021–6031.

Arriaga, S. D. R. M., Doe, J., and Smith, A. (2021). Ma-

chine learning techniques for fish behavior analysis.

Aquaculture Reports, 20.

Bartolom

´

e, E., Puigdueta, I., Gu

`

ardia, M., Estevez, M., and

Gomis, J. (2004). Effect of chronic transportation

stress on welfare and meat quality of weaned piglets.

Meat Science, 67(2):337–342.

Broom, D. (2011). Assessing welfare based on biological

principles. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental

Ethics, 24(1):215–227.

Dwyer, D. M. M., Ison, S. C., and Lawrence, S. A. (2000).

The use of a food competition test to assess social

rank in pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science,

66(4):297–308.

Hansen, M. F., Baxter, E. M., Rutherford, K. M. D., Futro,

A., Smith, M. L., and Smith, L. N. (2021). Towards

facial expression recognition for on-farm welfare as-

sessment in pigs. Agriculture, 11(9):847.

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Doll

´

ar, P., and Girshick, R. (2017).

Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International

Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pages 2961–

2969. IEEE.

Janssens, C. J., Helmond, F. A., and Wiegant, V. M. (1995).

The effect of chronic stress on plasma cortisol concen-

trations in cyclic female pigs depends on the time of

day. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol., 12(2):167–177.

Jong, I. C. D., Ekkel, E. D., Burgwal, J. A. V. D., Lambooij,

E., Korte, S. M., Ruis, M. A., Koolhaas, J. M., and

Blokhuis, H. J. (1998). Effects of strawbedding on

physiological responses to stressors and behavior in

growing pigs. Physiol. Behav., 64(3):303–310.

Liu, X., Wu, H., Chen, S., and Li, H. (2020). Automatic

recognition of stress in broiler chickens based on deep

learning. Sensors, 20(15):4251.

Manteca, X. and Alonso, D. (2000). Stress and meat quality

of pigs. Livestock Production Science, 65(2-3):239–

248.

Paszke, A., Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J.,

Chanan, G., Killeen, T., Lin, Z., Gimelshein, N.,

Antiga, L., Desmaison, A., K

¨

op, A., Yang, E. Z., De-

Vito, Z., Raison, M., Tejani, A., Chilamkurthy, S.,

Steiner, B., Fang, L., Bai, J., and Chintala, S. (2019).

Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep

learning library. CoRR, abs/1912.01703. [Online].

Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1912.01703.

Ruijven, T. and Oliehoek, K. (2017). Prenatal stress and

(neuro)epigenetic programming: Consequences for

behavior and social development. Neuroscience &

Biobehavioral Reviews, 80:604–616.

Ultralytics (2024). YOLOv8 Classification. [Online]. Avail-

able: https://docs.ultralytics.com/tasks/classify/.

Wang, H., Wu, S., and Zhang, Y. (2020a). Facial expres-

sion recognition for pig welfare assessment: A deep

learning approach. Animals, 10(12):2261.

Deep Learning-Based Classification of Stress in Sows Using Facial Images

395

Wang, H., Zhang, S., and Li, T. (2020b). Facial expression

recognition for pig welfare assessment: A deep learn-

ing approach. Animals, 10(12):2261.

Wechsler, B. (2000). The use of physiological measure-

ments in the assessment of animal welfare. Animal

Welfare, 9(2):203–210.

Weinstock, M. (2008). The long-term effects of prenatal

stress on offspring. Current Directions in Psycholog-

ical Science, 17(5):308–313.

Yang, J., Chen, X., and Zhao, F. (2020). Deep learning for

identifying cattle behavior in dairy farms. Computers

and Electronics in Agriculture, 173:105453.

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

396