MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research

Development with a Focus on Health

José Eurico de Vasconcelos Filho

1a

, Joel Sotero da Cunha Neto

2

and José Fernando Ferreira

2

1

Diretoria de cidadania e Cultura Digital, Fundação de Ciência Tecnologia e Inovação de Fortaleza, Fortaleza, Brazil

2

Vice-Reitoira de Pesquisa, Universidade de Fortaleza, Fortaleza, Brazil

Keywords: Interdisciplinary Research, User-Centered Design, Technological Development, eHealth.

Abstract: This study introduces MIDTs, an interdisciplinary method for technological research aimed at healthcare

applications. MIDTs integrates Design Science and User-Centered Design principles, structured into six

phases to ensure both scientific rigor and practical applicability. Over the last decade, it has been applied to

more than 70 projects, generating academic theses, patents, and clinical solutions. Empirical evidence

indicates that MIDTs fosters innovative and user-centered outcomes, effectively addressing complex societal

demands within healthcare. The method’s adaptability is further demonstrated through its potential

application in other sectors. By providing a clear framework for interdisciplinary collaboration and solution

development, MIDTs offers a robust approach to bridge research, practice, and user needs in technology-

driven health initiatives.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interdisciplinarity is considered of great

relevance for

the development of science, technology, and

innovation. Contemporary challenges, with their

inherent complexity, demand a diversified and

integrated perspective of knowledge.

Interdisciplinary studies are processes developed

to answer a question, solve a problem, or address a

broad or complex topic that cannot be adequately

handled by a single discipline. These studies rely on

disciplinary perspectives, which integrate their

knowledge and experience to produce a more

comprehensive understanding or cognitive

advancement (Repko, 2008).

The expansion of interdisciplinarity as a research

and teaching practice gained greater visibility as

disciplinary knowledge created dissatisfaction among

scientists, as it seemed insufficient to address the new

phenomena in society.

Thus, interdisciplinarity stands out in innovative

projects, where Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) play an important role in the

implementation of interdisciplinary projects. The

major needs of society, such as in health, housing,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6881-0814

transportation, financial services, entertainment, and

more, are being and will continue to be reinvented by

technology, increasingly accessible to all (Khosla,

2018). Interdisciplinary collaboration has been

identified as a critical driver for innovation,

particularly in addressing societal challenges that

demand integrated perspectives (Gorman & Groves,

2020).

Scientific knowledge (and research) aims to

develop theories with broad applications, whereas

technological knowledge is responsible for

developing theories with limited applications, aimed

at solving specific and often isolated problems,

primarily focused on technological innovation. In this

way, technological research is characterized as a

systematic and scientific process in search of

knowledge and solutions to technology-related

problems. It involves applying scientific principles

and methods to develop artifacts or products, often

specific, that respond to the demands, opportunities,

or problems of people or businesses. Technological

research can involve different fields of knowledge,

such as engineering, computer science, health,

biology, among others, and can be carried out both in

universities and research institutions as well as in

874

Filho, J. E. V., Neto, J. S. C. and Ferreira, J. F.

MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research Development with a Focus on Health.

DOI: 10.5220/0013336300003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 874-881

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

companies and industries. (Lebedev, 2018; Veugelers

& Wang, 2019)

The operation of systematizing and integrating

knowledge from distinct areas, to improve the

effectiveness of interventions, products, and services

offered to the community, requires an appropriate

method that directs efforts and competencies toward

optimizing results. (Fredericks, 2021)

In the academic context, one of the ways to

encourage and make interdisciplinary projects

feasible is the creation of methods and tools that

enable and systematize, with due rigor, the production

of technological artifacts that respond to specific

problems. In this perspective, the Coordination of

Training and Technological Innovation, in

partnership with the research group on Health

Technologies and Innovations, based at the Vortex

Laboratory of the Vice-Rectorate for Research at the

University of Fortaleza (UNIFOR), is responsible for

carrying out interdisciplinary projects, promoting the

integration of applied research with computational

resources in different areas, but with a strong focus

on health.

The Coordination began in 2012, fostering, over

time, the integration of interdisciplinary teams in

projects involving undergraduate and graduate

students (both Lato and Stricto Sensu - Master's and

Doctorate), as well as researchers from the areas of

Computer Science, Computer Engineering,

Marketing and Communication, Psychology,

Nursing, Medicine, Physiotherapy, Public Health,

Nutrition, Dentistry, and Speech Therapy. Based on

these diverse experiences and aiming to support

scientific and academic demands, the MIDTs -

Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research

Development with a Focus on Health - was conceived

to accommodate the nature and specificities of the

projects developed.

However, after the maturation of this method, its

adaptation became necessary. Its proven applicability

in multiple areas beyond health, as well as the

production of artifacts and results beyond those

initially highlighted, demanded evolutions in the

method. Thus, the scope of this method is expanded,

which, due to these changes, is now called MIDTs -

Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research

Development with a focus on health.

Given the above, this chapter aims to present

MIDTs, covering its conception, development, and

results. It is believed that the experience presented

here can inspire and support other researchers and

professionals in developing interdisciplinary projects

in a systematic and effective way.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

It can be stated that scientific research is aimed at

advancing scientific knowledge and understanding

reality and is closely tied to scientific theories, which

are subject to change. Technological research, on the

other hand, is focused on developing artifacts,

understood here not only as physical, tangible

products but also as intellectual ones, aimed at

controlling reality. This type of research is guided by

the task it aims to address and is thus considered by

some authors to be more precise than scientific

research. The product of technological research is

invariably the development of a new technology

(Freitas Junior et al., 2014).

In a similar view, Van Aken (2004) presents

Design Science as a research methodology focused on

developing artifacts or technological solutions to

practical problems, based on a rigorous scientific

methodology. The primary idea behind Design

Science is that science can be applied to create

solutions that address practical problems across

various fields, such as business, healthcare,

engineering, and more. The Design Science process

involves defining a problem, proposing a solution,

implementing and evaluating the proposed solution,

and disseminating the results obtained. This approach

is widely used in areas like software engineering,

information systems, project management, and

entrepreneurship.

The knowledge generated from the foundations of

Design Science also contributes to advancing

research based on applied knowledge and solutions

that respond to problems and demands from the

market and society. This is multidisciplinary

knowledge, where research focused on this type of

knowledge aims to solve relevant complex problems,

considering the context in which their results will be

applied. Consequently, the knowledge developed by

Design Science Research is not descriptive-

explanatory; it is prescriptive.

In this sense, Design Science Research constitutes

a rigorous process of designing artifacts to solve

problems, assessing what has been designed or what

is functioning, and communicating the results

obtained (Çağdaş & Stubkjær, 2011). Design science

research bridges the gap between theory and practice,

providing a systematic approach for developing

artifacts that address practical problems while

contributing to academic knowledge (Hevner &

Gregor, 2020).

Despite their similarities, technological research

and design science are different approaches to solving

technology-related problems. While technological

MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research Development with a Focus on Health

875

research is broader and involves the application of

scientific principles and methods for developing new

products, processes, and services, design science is

more specific, focusing on solving practical problems

through the creation of technological solutions based

on a rigorous scientific methodology.

These approaches have much to contribute to

proposing methods and tools that foster

interdisciplinarity and the construction of sometimes

innovative artifacts that improve the lives of

individuals, institutions, and businesses.

2.1 User-Centered Design

Design Science and User-Centered Design (UCD) are

complementary approaches that underpin the

development of innovative and practical solutions in

interdisciplinary research. Design Science, as defined

by Van Aken (2004), emphasizes the creation of

artifacts or technological solutions to address

practical problems using rigorous scientific methods.

This process involves defining a problem, designing

a solution, evaluating its effectiveness, and

disseminating findings, aiming to produce

prescriptive knowledge applicable across fields such

as healthcare, business, and engineering.

Similarly, UCD prioritizes the needs and

experiences of end users throughout the design

process. Coined by Norman and Drape (1986), it is a

philosophy and framework that emphasizes iterative

development, interdisciplinary collaboration, and

continuous user feedback. While Design Science

provides a structured methodology for artifact

creation, UCD ensures that these artifacts are user-

centered and contextually relevant, bridging the gap

between technical solutions and human-centric

design. Together, these approaches from the

theoretical foundation of the MIDTs methodology,

enabling the development of effective, innovative,

and user-friendly solutions. The term UCD was

coined by Donald Norman in his research lab at the

University of California (Norman and Drape, 1986).

Notably, UCD underpins Interaction Design

strategies (Preece, Rogers and Sharp, 2015), such as

the Interaction Design Lifecycle Model and Design

Thinking (Kimbell, 2011; Tschimmel, 2012).

UCD can be characterized as a multi-stage

problem-solving process where usability goals, user

characteristics, environment, tasks, and workflow of

a product, service, or process receive thorough

attention at each stage of the design process.

The main difference from other design

philosophies is that UCD attempts to optimize the

product around how users can, want to, or need to use

it, rather than forcing them to change their behaviors

(as long as they are correct) to accommodate the

product.

Some principles indicate that a design proposal is

user-centered, such as:

● The design is based on an explicit

understanding of users, tasks, and

environments;

● Users are involved throughout the design and

development process;

● The design is directed and refined by user-

centered evaluation;

● The process is iterative;

● The design addresses the entire user

experience; and

● The design team includes multidisciplinary

skills and perspectives.

These principles are essential for projects aimed

at quality user satisfaction. It is also inherent to

UCD's philosophy to accommodate different

perspectives and knowledge, promoting the

participation not only of the user in the process but of

the entire, interdisciplinary design team. Thus, UCD

conceptually supports the process presented here. The

application of UCD principles in healthcare has been

shown to improve usability and adoption by actively

involving end users throughout the development

process (Bazzano et al., 2021).

3 INTERDISCIPLINARY

METHOD FOR THE

DEVELOPMENT OF HEALTH-

FOCUSED TECHNOLOGIES

The Health Technologies Research Group, affiliated

with the Technology Directorate of the University of

Fortaleza, where the process presented herein

originates and develops, was established in 2012 with

the aim of supporting applied research projects in the

ICT field (or involving ICTs) on the University

campus.

Initially, it consisted only of students and

researchers from the fields of Computer Science and

Engineering. However, during the first year of

activity, it was observed that the development of

interactive systems in the academic context was an

interdisciplinary process. This realization opened

space for students, professionals, and researchers

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

876

from the areas of Marketing, Communication, and

Administration, who joined to contribute knowledge

and experience.

Over time, the laboratory began receiving project

demands, mostly academic, from various fields,

predominantly health (e.g., Psychology, Medicine,

Public Health, Physiotherapy, Speech Therapy,

Nursing, and Dentistry). This interdisciplinary

demand required specific tools to accommodate the

specific needs of the involved areas and the academic

environment.

In this context, in 2015, the Academic Integration

Program was created, leading to the conception of

MIDTs – Interdisciplinary Method for the

Development of Health-Focused Technologies. The

focus on health stemmed from the proliferation of

cases in the area.

3.1 Scientific Framework of the

Methodology

The scientific framework of the proposed

multimethod methodology is significant, given its

adherence to academic research and technological

development processes, which is one of its

distinguishing features. Regarding the approach, the

methodology accommodates both quantitative and

qualitative research, as the data obtained can be

analyzed numerically using statistics—click counts,

interaction time, errors (Sampieri, Collado and

Lucio, 2013)—or through a study involving a

statistically valid sample population and/or data

revealing user perceptions and experience quality,

which are not entirely quantifiable (Minayo, 2014).

Its nature is applied, as it generates hypotheses

and specific solutions (artifacts) for concrete

problems, producing multidisciplinary and

prescriptive knowledge.

Regarding its objectives, MIDTs proposes

technological research, focusing on the development

of multidisciplinary, applied knowledge aimed at

artifact-based solutions for complex problems and

specific societal demands. Validation and/or

evaluation of tools and research strategies aim at

creating reliable instruments (in this case, the

technological artifact) that are accurate and usable,

which can be employed by other researchers and

users (Polit; Beck, 2018; Wazlawick, 2014). (Freitas

Junior et al., 2014; Van Aken, 2004).

As for procedures, the method proposes

bibliographic research in its phases, positioning the

researcher in relation to the investigated problem

through information not previously available. It also

considers itself experimental, given the perspective of

introducing technology controlled by the researcher

into the context under investigation (Wazlawick,

2014).

3.2 Proposed Process

MIDTs is inspired by academically inclined

approaches such as Interaction Design (Preece,

Rogers, Sharp, 2015), Design Science Research, and

market-oriented methods such as Design Thinking

(Kimbel, 2011; Tschimmel, 2012), conceptually

anchored in User-Centered Design. The method

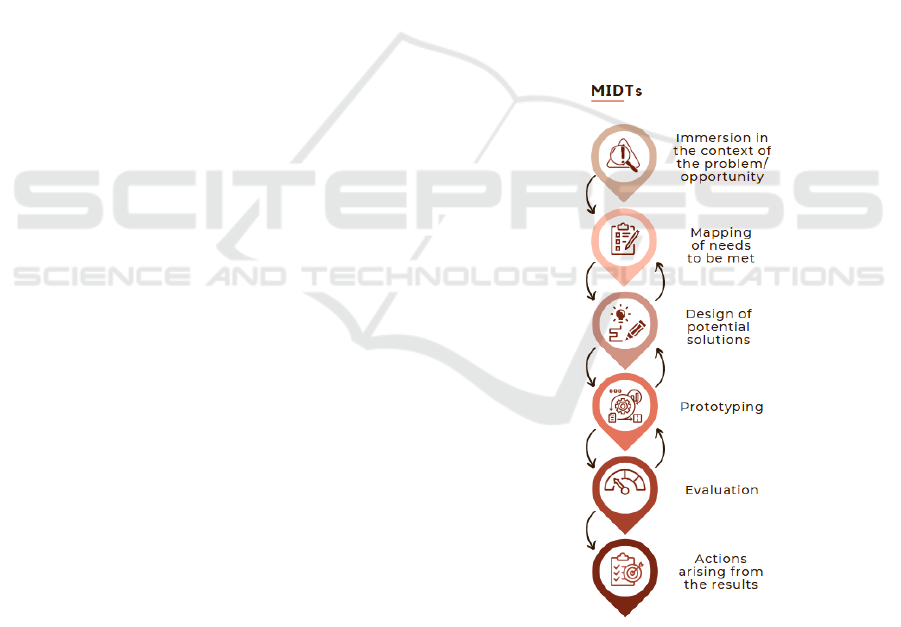

proposes six phases (Figure 3), each with specific

inputs and outputs that feed into subsequent phases or

contribute to revising the output of the preceding

phase. The ultimate goal of the process is to develop

a functional prototype to test a research hypothesis.

Delivering a market-ready product is not the initial

scope of the methodology, though the process can be

adapted for such purposes, adhering to necessary

legal and regulatory aspects.

Figure 1: Framework of method activities.

The First Phase consists of understanding the

context of the problem at hand, based on scientific

evidence and market data. It is common at the

beginning to lack clarity about the problem and

potential solutions, only a superficial perception of a

need. Therefore, meetings are held with an

MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research Development with a Focus on Health

877

interdisciplinary team of specialists to clearly identify

the problem and its possible causes, as well as align

this understanding among the team. Based on this, a

hypothesis is established that emerging technologies

such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of

Things (IoT) have shown great potential in driving

innovation in interdisciplinary methods, enabling

scalable and adaptive solutions to complex problems

(Sarker et al., 2022).

Based on preliminary discussions, the hypothesis

is used as a guiding question for a systematic review

(Staples; Niazi, 2007) or integrative review (Torraco,

2005) of the literature, using scientific databases and

portals to deepen the theoretical understanding of the

topic and identify existing similar solutions. As a

result, the scientific validation of the problem and

potential solution alternatives are expected.

Consider the following example of a problem:

injuries caused by falls in elderly individuals in home

care settings, observed by a master's student in

nursing working for a health cooperative. In the first

phase, the student conducted a root cause analysis to

identify the motivations behind the falls. With data

from the cooperative and interdisciplinary team

support, it was identified that the falls occurred due to

multiple causes, including the lack of a dedicated

caregiver, who had to step away for other domestic

duties such as meal preparation. Consequently,

specialists proposed a monitoring system using IoT

(Internet of Things) for fall detection and prevention.

Using this hypothesis, the student searched scientific

databases such as Google Scholar, Elsevier, and

others specific to health to identify similar research

and solutions that could support her work. She found

technologies aiding fall detection but none for

prevention. With this result, she moved on to the

second phase.

The Second Phase involves identifying user needs

(target audience) and establishing requirements to

solve the identified problem. Methods to identify

these needs include: 1) interviews and focus groups

with potential users (aligned with designed profiles),

2) creation of personas and usage scenarios (Barbosa

and Silva, 2011) by the interdisciplinary team (Carrol,

2006), and 3) market data research. Based on these

needs, specialists analyze and define the

technological requirements (functional and non-

functional) of the solution. These requirements are

used to structure a matrix, comparing solutions found

in the market and academia, indicating full, partial, or

unmet requirements.

Continuing the example, the nursing student

conducted a needs assessment through interviews

with cooperative clients. These interviews revealed

that families did not adopt existing preventive

techniques like physical bed restraints, as they were

deemed invasive and uncomfortable, compromising

the elderly's quality of life. Additionally, the routine

of the elderly included natural activities like hygiene

and meals. Based on these reports and other needs,

the team mapped functional and non-functional

requirements for the system. For instance, a non-

functional requirement was non-invasive monitoring

that preserves the patient's privacy and quality of life,

while a functional requirement was the ability to

temporarily pause and resume monitoring to

accommodate caregiving routines. With these

requirements, the student revisited her research and

confirmed that existing technologies did not meet all

mapped requirements, justifying the development of

new technology, and proceeding to the next phase.

The Third Phase encompasses the ideation

process to design the initial solution. Based on the

requirements and alternative technologies identified

in earlier phases, the interdisciplinary team meets to

conduct brainstorming sessions (Godoy, 2001) to

devise a solution. Initial drafts are created according

to the technology (e.g., low-fidelity app screen

prototypes (Barbosa and Silva, 2011), schematic

drawings of small hardware devices, etc.). The group

validates these drafts with potential users and refines

them as needed to ensure the solution makes sense.

When a viable theoretical solution is achieved, a

more refined version is produced. The team specifies

components such as electronic hardware, visual

identity (if applicable), color palette, and other details

to enhance fidelity to the final product.

In the fall prevention system case, the last phase

concluded with mapped requirements. In the third

phase, the team produced a general architecture of the

solution, listing necessary components to satisfy the

requirements. Low-fidelity drafts were conceptually

validated, followed by high-fidelity versions closer to

the final output. Using the same approach, low- and

high-fidelity versions were created for each

component of the architecture, such as information

panel screens. With the designs completed, the team

proceeded to the next phase.

The Fourth Phase proposes the development of an

interactive or functional prototype, which may also

take the form of a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

(Ries, 2011), based on a selected design proposal. At

this stage, the technological architecture of the

solution is defined, including the development

environment and platform, tools, programming

languages, software components (libraries, database

management systems, frameworks), hardware design

and components, or other technical artifacts

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

878

associated with the product. The resulting

deliverables typically include software

documentation, hardware schematics, source code, or

other technical materials detailing the proposed

technological artifact.

In some cases, the project does not advance to the

physical development or coding of the artifact but

instead creates an interactive simulation of the

artifact's behavior using specific software (e.g.,

Figma). This strategy reduces project costs and time

but may negatively impact the ability to conduct

evaluations or tests requiring functional technology.

In the nursing master's student example, the team

developed each technological component defined in

Phase 3. The application's backend logic was created,

high-fidelity screens were implemented (frontend),

and hardware components were integrated and

housed in custom 3D-printed enclosures.

The Fifth Phase involves evaluating the produced

artifact using specific tools and methods, such as

usability evaluation (Barbosa and Silva, 2011),

content evaluation by judges, utility/acceptation

evaluation (Saravanos, 2022), and clinical validation

through a pilot study. These evaluations aim to

comprehensively assess the artifact, determining

whether it is easy, understandable, and pleasant to use

for its target audience, whether the content and

processes it proposes are scientifically correct and

appropriate from the perspective of experts, and

whether it is useful for the intended activity.

The proposed methods are complementary, each

offering a distinct perspective on the technology. A

careful assessment of what needs to be measured and

the available time is essential. However, all methods

share common steps, typical of any evaluation

process: selecting participants, ensuring a sufficient

and representative sample of project personas,

avoiding selection biases, and considering factors like

age range, familiarity with technology, or the project

itself. Additionally, obtaining appropriate consent

and assent forms is crucial. Some methods also

include standard scales, such as the System Usability

Scale (SUS), which have specific calculation

methods for results.

For the fall prevention project, acceptance model

(Saravanos et al., 2022) was used as a reference. Eight

health professionals (nurses, physicians, and

physiotherapists) participated in the evaluation. The

test was conducted in a controlled laboratory

environment to capture interaction nuances with the

technology. The results showed 88% total agreement

among evaluators, with suggestions for

improvements such as mobile device connectivity,

battery use in case of power outages, and the

generation of reports.

The Sixth Phase involves compiling and

presenting the results obtained, typically in the form

of course completion works, master's dissertations,

doctoral theses, or scientific articles. As a result of

this methodology, some executed projects present

prototype solutions to real problems, extending

beyond hypothesis testing. This sometimes enables

software, trademark, or patent registrations and

product market placement. Activities conducted in

this phase are not limited to the project's end but can

be performed at the conclusion of other phases,

depending on the publication locus and format.

In the same fall prevention project example, the

results of a proof of concept conducted before the

fourth phase were used to write an article for a

scientific initiation event. After training the neural

network with real human data to parameterize the

system, a second article was produced for a national-

scale event. At the project's end, the student

completed and presented her dissertation to an

examining committee, which awarded her a master's

degree. Although no specific brand was developed, a

patent application was submitted through the

University with consent from all involved, given the

perceived applicability of the concept to other

contexts, such as baby fall prevention.

3.3 Ethical Aspects

Regarding ethical and legal aspects, all research

supported by the method proposed herein adheres to

the ethical and legal standards for research involving

human subjects. In Brazil, these must comply with the

guidelines and regulatory norms outlined in

Resolution No. 466, of December 12, 2012, by the

National Health Council, which provides Guidelines

and Regulatory Norms for Research Involving

Human Beings (Brasil, 2013).

4 RESULTS

The MIDTs has been refined and utilized by the

research group of the Vice-Rectorate for Research at

the University of Fortaleza for approximately ten

years. The outcomes achieved with MIDTs

throughout its application are significant and span

various areas.

The results achieved through the application of

MIDTs are noteworthy, encompassing over 70

applied research projects. These have led to nine

trademark registrations, 86 academic publications,

MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research Development with a Focus on Health

879

and practical technological artifacts currently in use

in hospitals, clinics, and public health programs. For

example, IoT-based systems for fall prevention and

monitoring have demonstrated tangible benefits for

healthcare providers and patients.

In 2020, with the aim of sharing experiences in the

development and use of eHealth technologies with the

scientific community—most of them supported by

the method presented here—the book "eHealth

Technologies in the Context of Health Promotion"

(Silva, Brasil and Vasconcelos Filho, 2020) was

published.

Furthermore, the method has contributed to the

direct and indirect training of students from diverse

fields, promoting interdisciplinarity and innovation.

These results highlight MIDTs’ potential to transform

academic research into real-world solutions that

address concrete societal demands.

Currently, several other projects are at different

stages of development within the Program, utilizing

the method presented here.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate that the MIDTs

methodology effectively integrates interdisciplinary

approaches and develops innovative technological

solutions, particularly in the healthcare sector.

However, analyzing its impact over a decade of

application reveals gaps and opportunities that

warrant critical reflection.

Firstly, the predominant application in the

healthcare field highlights a lack of exploration in

other domains, such as education, public

administration, and sustainability. This limitation

may stem from the method's initial framework, which

prioritized challenges and solutions tailored to

healthcare needs. Methodological adaptations are

necessary to broaden its scope, incorporating tools

like blockchain to enhance data security and

emerging technologies like generative AI for solution

scalability.

Another critical aspect is the ethical

considerations in technological development. It was

observed that aspects such as privacy, inclusion, and

sustainability were not consistently addressed in the

early phases of the method. Integrating these

concerns from the problem-identification stage can

mitigate risks and ensure solutions are more

responsible and aligned with societal demands.

Furthermore, despite the success in generating

technological artifacts and academic publications, the

absence of consistent metrics to measure social and

economic impacts limits a comprehensive assessment

of its outcomes. To advance, it is suggested to

implement indicators such as operational cost

reductions, improvements in health indicators, and

usability perceptions from end-users.

These analyses reinforce the relevance and

capability of MIDTs in addressing complex

challenges while highlighting areas for evolution to

ensure its effectiveness and sustainability in diverse

contexts.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study presented the MIDTs methodology as an

interdisciplinary and user-centered framework

designed for the development of technologies in the

healthcare sector. Evidence collected over a decade

indicates that the method has significantly

contributed to advancing technological solutions,

resulting in academic publications, patent

registrations, and practical applications. Additionally,

it has fostered interdisciplinary training for students

and researchers, promoting collaboration across

diverse knowledge areas.

It is concluded that to ensure the method's

evolution, it is crucial to address identified

limitations, including its expansion to other sectors,

the integration of emerging technologies, and the

inclusion of metrics for social and economic impact.

These improvements will contribute to consolidating

MIDTs as a robust and adaptable tool for

interdisciplinary technological development, aligned

with contemporary demands.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the researchers and

students who participated, either directly or

indirectly, in the design and practical application of

the method, contributing to its evolution.

REFERENCES

Barbosa, S., & Silva, B. (2010). Interação humano-

computador. Elsevier Brasil.

Bazzano, A. N., et al. (2021). User-centered design in

global health: Innovative methods to engage end users

in the development of digital health tools. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 23(3), e18974.

https://doi.org/10.2196/18974.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

880

Beck, K., et al. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software

Development. Disponível em:

http://agilemanifesto.org/. Acesso em: 17 nov. 2023.

Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde.

(2013). Resolução nº 466/2012 que trata de pesquisas e

testes em seres humanos. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde.

Çağdaş, V., & Stubkjær, E. (2011). Design research for

cadastral systems. Computers, Environment and Urban

Systems, 35, 77–87.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2010.07.003

Carroll, J. M. (2006). Dimensions of participation in

Simon's design. Design Issues, 22(2), 3–18.

Fredericks, Suzanne. "Using knowledge translation as a

framework for the design of a research protocol.".,

2021. https://doi.org/10.32920/ryerson.14668878.v1

Freitas Júnior, V., et al. (2014). A pesquisa científica e

tecnológica. Espacios, 35(9), 12.

Godoy, M. (2001). Brainstorming. Editora de

Desenvolvimento Gerencial.

Gorman, M. E., & Groves, J. F. (2020). Innovation through

interdisciplinarity: Developing sustainable solutions for

societal challenges. Research Policy, 49(7), 104079.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104079.

Hevner, A., & Gregor, S. (2020). Design science research

contributions: Finding a balance between artifact and

theory. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 21(5), 1018–1038.

https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00659.

Khosla, V. (2020). Reinventing societal infrastructure with

technology. Medium.

Kimbell, L. (2011). Rethinking design thinking: Part I.

Design and Culture, 3(3), 285–306.

Lebedev, С. А., et al. "Levels of organization of scientific

knowledge". Proceedings of the International

Conference on Contemporary Education, Social

Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2018), 2018.

https://doi.org/10.2991/cesses-18.2018.186

Minayo, M. C. (2014). Apresentação. In R. Gomes,

Pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. São Paulo: Instituto

Sírio Libanês.

Norman, D. & Draper, S. (1986) (Eds.). User centered

system design; new perspectives on human-computer

interaction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates Inc.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2018). Fundamentos de

pesquisa em enfermagem: Avaliação de evidências

para a prática da enfermagem (9ª ed.). Porto Alegre:

Artmed.

Preece, J., Sharp, H., & Rogers, Y. (2015). Interaction

design: Beyond human-computer interaction. John

Wiley & Sons.

Repko, A. F. (2008). Interdisciplinary research: Process

and theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Ries, Eric (2011). The Lean Startup. United States of

America: Crown Business. p. 77. 2011

Sampieri, R. H., Collado, C. F., & Lucio, M. P. B. (2013).

Metodologia de pesquisa (5ª ed.). Porto Alegre: Penso.

Saravanos, A., Zervoudakis, S., & Zheng, D. (2022).

Extending the Technology Acceptance Model 3 to

Incorporate the Phenomenon of Warm-Glow.

Information, 13(9), 421.

Sarker, I. H., et al. (2022). Machine learning and AI in IoT:

Current state and future directions. Internet of Things

Journal, 9, 1458–1475.

https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3083576

Silva, R. M., Praça, C., & Vasconcelos Filho, J. E. (2020).

eHealth technologies in the context of health

promotion. Fortaleza: edUECE.

Silva, J. R., Brasil, C. C. P., Brasil, B. P., Paiva, L. B.,

Oliveira, V. F., Vasconcelos Filho, J. E., & Santos, F.

W. R. (2018). Avaliação do aplicativo Doe sangue por

especialistas. In 7º Congresso Ibero-Americano em

Investigação Qualitativa - CIAQ 2018, Fortaleza, CE.

Staples, M., & Niazi, M. (2007). Experiences using

systematic review guidelines. Journal of Systems and

Software, 80(9), 1425–1437.

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews:

Guidelines and examples. Human Resource

Development Review, 4(3).

Tschimmel, K. (2012). Design thinking as an effective

toolkit for innovation. In Proceedings of the XXIII

ISPIM Conference: Action for Innovation: Innovating

from Experience, Barcelona.

Van Aken, J. E. (2004). Management research based on the

paradigm of the design sciences: The quest for field-

tested and grounded technological rules. Journal of

Management Studies, 41(2), 219–246.

Veugelers, R. and Wang, J. "Scientific novelty and

technological impact". Research Policy, vol. 48, no. 6,

2019, p. 1362-1372.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.01.019

Wazlawick, R. (2014). Metodologia de pesquisa para

ciência da computação (2ª ed.).

MIDTs: Interdisciplinary Method for Technological Research Development with a Focus on Health

881