Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated

Signals

S. V. Bozhokin

1a

, I. B. Suslova

2b

, A. A. Riabokon

1c

and T. D. Shokhin

1d

1

Institute of Physics and Mechanics, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, 195251 St. Petersburg, Russia

2

World-Class Research Center for Advanced Digital Technologies, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University,

195251 St. Petersburg, Russia

Keywords: Heart Rate Turbulence, Continuous Wavelet Transform, Local Frequency.

Abstract: This paper presents new approaches to the analysis of non-stationary heart rate variability (HRV) taking into

account strong time variation in the duration of RR intervals, which is associated with extrasystoles. A

mathematical model of a frequency-modulated signal comprising of identical Gaussian peaks unevenly spaced

along the time axis is applied to the phenomenon of heart rate turbulence (HRT). The maxima of the Gaussian

peaks correspond to the moments of real heart contractions. A time-continuous function of local

(instantaneous) heart rate frequency is calculated by analyzing the maxima of the continuous wavelet

transform applied to such a model signal. The change in local frequency over time is proposed as a new

characteristic of extrasystoles and compensatory pauses in the heart tachogram. The proposed method, applied

in this work to study tachogram records with extrasystoles, can be used in the analysis of any other heart

rhythm disturbances.

1 INTRODUCTION

Heart rate turbulence (HRT) is of considerable

interest in cardiology for the diagnosis of life-

threatening conditions, attracting the attention of both

practicing physicians and multidisciplinary

researchers. HRT is associated with significant

disturbances in heart rhythm frequency, such as

extrasystole (Schmidt et al., 1999; Bauer et al., 2008;

Disertori et al., 2016; MA, 2004; Cygankiewicz &

Zaręba, 2006; Cygankiewicz, 2013; Germanova et

al., 2021; Huikuri et al., 2001). Extrasystole is a

premature excitation of the heart caused by the

mechanism of repeated entry of electrical excitation

(re-entry). The essence of the re-entry mechanism is

that the electrical impulse repeatedly enters a section

of the myocardium or the conduction system of the

heart, creating a circulation of the excitation wave.

The relationship between cardiovascular risk factors

and heart rate variability (HRV) in patients with heart

failure has been shown in many scientific studies

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5653-6574

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4497-1867

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-6948-6200

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3348-7603

(Zeid et al., 2024; Thayer et al., 2010; Kubota et al.,

2017; Huikuri & Stein, 2013; Turcu et al., 2023; Yan

et al., 2023; Lombardi & Stein, 2011). Many rather

complex mathematical methods have been developed

and applied for quantitative analysis of HRV based

on processing of electrical signals of the heart.

Recently, various combinations of time-frequency,

nonlinear and neural network methods have been

actively used. Comparison of various methods and

the results of their application in the study of HRT

shows the presence of classification errors and

difficulties in comparing the results obtained for

different groups of patients by different methods

(Blesius et al., 2020; Acharya et al., 2006; Sauerbier

et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2014; Koyama et al., 2002;

Tsvetnikova et al., 2008).

The problem of studying extrasystole includes

both ECG analysis in terms of PQRST complex

morphology and the analysis of variations in RR

interval duration. It should be noted that in both atrial

(APV) and ventricular (VPC) extrasystole, a

1038

Bozhokin, S. V., Suslova, I. B., Riabokon, A. A. and Shokhin, T. D.

Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated Signals.

DOI: 10.5220/0013342700003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 1038-1045

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

significant change in the RR intervals is observed

before and after the ectopic contraction.

In this paper, we present new characteristics of

non-stationary heart rate variability (NHRV)

obtained from the analysis of non-stationary rhythmic

features of the tachogram RR - intervals with

extrasystoles. When monitoring the state of the

cardiovascular system, measuring heart rate is quite

convenient and simple. As a model of NHRV we

consider the model of frequency modulated

tachogram signal. In the proposed tachogram model,

we do not exclude from the analysis the time intervals

of the extrasystoles themselves, as well as the

compensatory pauses following the extrasystoles.

The research works (Schmidt et al., 1999; Zeid et

al., 2024; Blesius et al., 2020; Sauerbier et al., 2024;

Yin et al., 2014) provide reference values for

prognostic parameters: the onset of turbulence (TO)>

0%, the slope of turbulence (TS) < 2.5 ms/RR, which

indicate the increase in the risk of heart failure. It

should be noted that these reference values may differ

for atrial and ventricular extrasystoles. The HRV

Standards (Electrophysiology, 1996) state that when

processing the ECG signal, “ectopic beats,

arrhythmic events, missing data and noise effects…

should be removed from the recording. Short-term

recordings that are free of ectopia, missing data and

noise are preferred.” However, the Standards

(Electrophysiology, 1996) allows for the influence of

ectopia on the results. In this case, it is proposed to

indicate the relative number and relative duration of

RR intervals that were missed and interpolated.

Along with this, some authors (Milaras et al., 2023)

point out the necessity of taking into account the

duration of the compensatory pause, and extrasystole

itself, since these areas provide important information

about the change in the frequency spectrum of the

signal, and, consequently, about the physiological

state of the patient. The authors of this article believe

that the phenomenon of heart rhythm turbulence HRT

occurs at the first contraction of the rhythmic interval,

expressed as a premature contraction of the heart, and

ends after the normalization of the sinus rhythm. The

approximate transition period for heart rhythm

stabilization after an extrasystole is about 20

heartbeats.

In this paper, we propose a new approach to study

the properties and new quantitative characteristics of

the heart rate tachogram signal to obtain

diagnostically important information about HRT, not

excluding the time segments of extrasystoles. Within

the framework of this approach, the tachogram model

is a frequency-modulated signal (Bozhokin &

Suslova, 2014; Bozhokin et al., 2012, 2020, 2018),

where QRS complexes are represented as Gaussian

peaks unevenly distributed on the time axis. The

uneven distribution of peaks reflects frequency

modulation of the signal. The proposed model differs

significantly from the generally accepted model of a

signal with amplitude modulation (Addison, 2005;

Cartas-Rosado et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021) and

leads to different spectral characteristics of the signal.

This is especially noticeable in long-term cardiological

tests with a strong trend in the RR-interval sequence.

The signal is processed in time-frequency domain by

means of the continuous wavelet transform CWT

(Bozhokin & Suslova, 2014; Bozhokin et al., 2012,

2020, 2018). The proposed model allows us to derive

CWT of the signal in the analytical form and to analyze

the wavelet spectrum by calculating so-called local

frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

, which corresponds to the

maximum CWT for each time point throughout the

entire period of the pulse rate registration without any

exceptions. It should be noted that in the works

(Schmidt et al., 1999; MA, 2004; Sauerbier et al., 2024;

Yin et al., 2014), extrasystoles are characterized by

only two parameters TO and TS, which do not take into

account the extrasystoles themselves and subsequent

compensatory pauses, namely 𝑅𝑅

and 𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

intervals. In the present article, the behavior of local

frequency function 𝐹

(𝑡) depends significantly on

both 𝑅𝑅

and 𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

, since it is calculated for any

moment in time.

The change in local frequency over time can be

used to solve the problem of identification and

classification of extrasystoles, since it is calculated

over the entire period of heart rate registration

without any exceptions. This approach can be applied

to study all types of arrhythmias.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Tachogram Records Used in This

Work

This article is based on the analysis of approximately

70 tachogram records that contain extrasystoles. The

records of such tachograms are provided in the book

(Shubik & Tikhonenko, 2019). This collection

includes a large set of examples of various heart

rhythm and conduction disturbances that are most

often registered when analyzing Holter monitoring

records. In this article, we take a closer look at only

two examples of HRT from (Shubik & Tikhonenko,

2019): the tachogram with one extrasystole and that

with three extrasystoles.

Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated Signals

1039

2.2 Algorithm for Calculating Local

Frequency in the Case of a

Tachogram with One Extrasystole

To analyze non-stationary heart rate record (HRV)

with extrasystoles, we consider

𝑍

(

𝑡

)

as a continuous frequency-modulated signal

(FMS), which depends on time 𝑡, instead of the

traditional HRV model as a discrete amplitude-

modulated signal (AMS). The signal 𝑍(𝑡) is a set of

identical Gaussian peaks with the centers located on

an uneven time grid and coinciding with the true

moments of heartbeats 𝑡

=𝑡

+𝑅𝑅

, where 𝑅𝑅

are the time intervals between heartbeats, 𝑛=

0,1,2,…𝑁 − 1, 𝑡

=0, and 𝑁 is the number of

heartbeats. Note that the total number of Gaussian

peaks is 𝑁+1, since the maximum of the first

Gaussian peak happens at 𝑡

=0.

𝑍

(

𝑡

)

=

∑

𝑧

(

𝑡−𝑡

)

, (1)

𝑧

(

𝑡−𝑡

)

=𝑒𝑥𝑝−

(

)

. (2)

For such a model, all Gaussian peaks, separated

by different intervals 𝑅𝑅

, have the same unit

amplitude and the same width 𝜏

= 0.02 𝑠, equal to

the average width of QRS complex.

Let us consider a sequence of 𝑁=7 heartbeats,

which is a vector 𝑅𝑅

= {996, 981, 934, 401, 1284,

891, 895}, where all 𝑅𝑅

have millisecond dimension

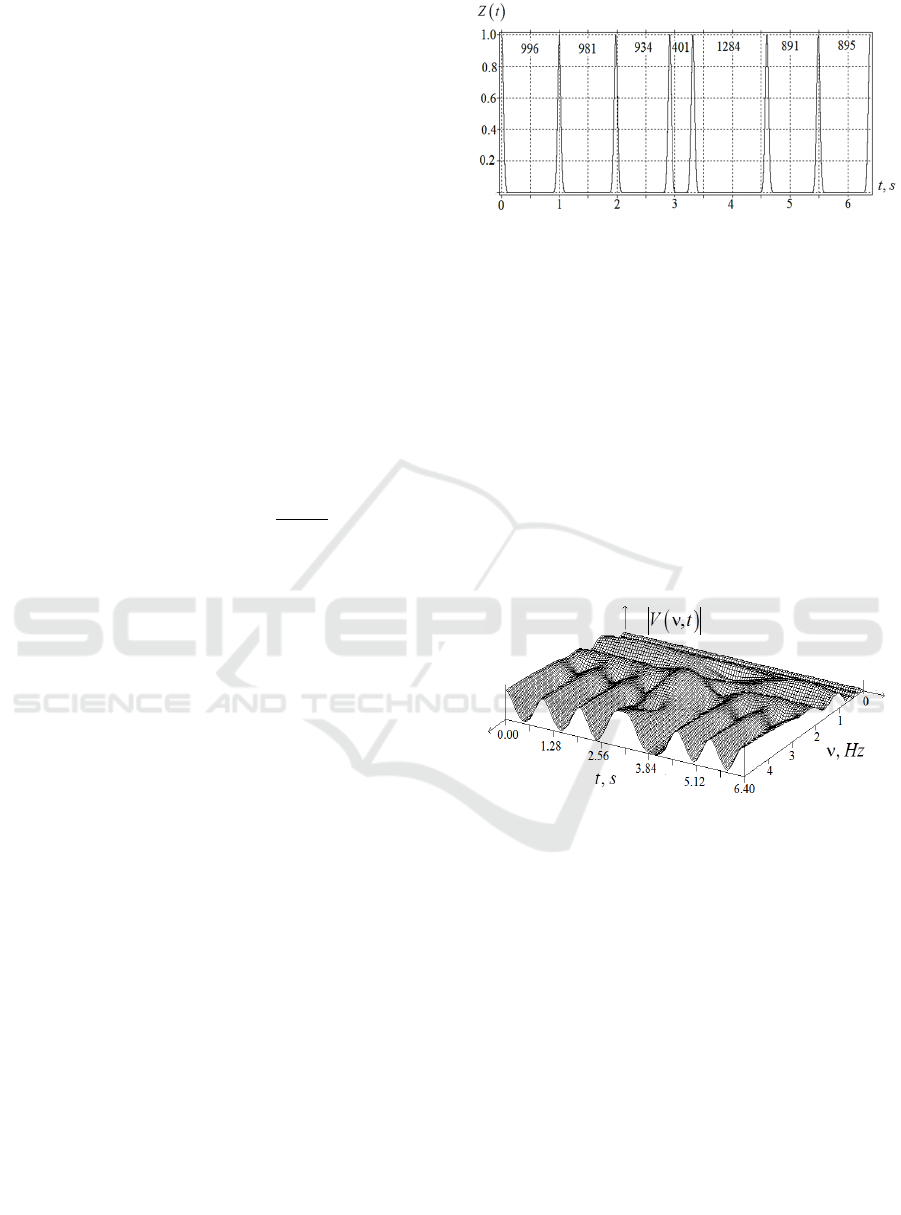

(Fig.1).

Among 𝑅𝑅

values, 𝑛 = 0,1,2,…𝑁 − 1, 𝑡

=0,

there is a premature cardiac contraction, preceded by

the interval 𝑅

= 401 𝑚𝑠. Thus, we fix the only

extrasystole with the beat number 𝑛=

4 in the series. After a strong non-stationarity

𝑅

= 401 𝑚𝑠, a long compensatory pause

𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

= 1284 𝑚𝑠 occurs, and 𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

≫𝑅𝑅

.

Note that real cardiac contractions are located on an

uneven grid of discrete times 𝑡

(Bozhokin &

Suslova, 2014; Bozhokin et al., 2012, 2020, 2018).

Fig.1 shows frequency-modulated signal

𝑍

(

𝑡

)

(FMS) related to the tachogram with a single

extrasystole 𝑅

= 401 𝑚𝑠 and the time of

premature heartbeat 𝑡

=3.31 𝑠. In this signal, the

heart contractions occur at time moments 𝑡

=

𝑡

+𝑅𝑅

, where 𝑅𝑅

are determined by 𝑅𝑅

.

Fig.1 clearly indicates the difference between

frequency modulated signal (FMS) used in this article

and amplitude modulated signal (AMS) considered in

the Standards (Electrophysiology, 1996).

Figure 1: Continuous model of FMS for the tachogram with

a single extrasystole 𝑅

=401 ms.

The analytical expression

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

of the

continuous wavelet transform with the Morlet mother

wavelet function, where 𝜈 is the frequency, measured

in Hz, and 𝑡 is the time in s, was derived for the

irregular system of Gaussian peaks in (Bozhokin &

Suslova, 2014; Bozhokin et al., 2012, 2020, 2018).

Fig.2 shows the wavelet spectrum

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

for the

continuous signal 𝑍

(

𝑡

)

(Fig.1) in time-frequency

domain. We use the Morlet mother wavelet function

in the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) because

such a wavelet gives the correct positions of the

maxima in frequency and time for simplest non-

stationary signals.

Figure 2: CWT for the system of Gaussian peaks (Fig.1),

where 𝜈 is measured in Hz, and 𝑡 in s.

The frequency corresponding to the maximum

value of

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

is found. This so-called local

(instantaneous) frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

depends on time.

Although the usual sinus rhythm contains both

spectral components of low-frequency VLF= (0.015;

0.04 Hz), mid-frequency LF= (0.04;0.15 Hz), and

high-frequency HF= (0.15; 0.4 Hz), the calculations

of 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

in this case do not lead to great

difficulties (Bozhokin & Suslova, 2014; Bozhokin et

al., 2012, 2020, 2018). However, in the case of

extrasystole (Fig.1), the behavior of

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

(Fig.2)

near the extraordinary time moment 𝑡

=3.31 𝑠 has

more complex nature. This entails difficulties in

calculating the local frequency 𝜈=𝐹

(

𝑡

)

near the

critical time moment 𝑡

= 3.31 𝑠. To calculate

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

for a signal with an ectopic Gaussian peak,

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

1040

we should formulate criteria that will determine upper

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

and lower 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

limits for local frequency

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

:

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

≤𝐹

(

𝑡

)

≤𝐹

(

𝑡

)

.

The difficulties

in determining the boundaries 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

and 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

are

due to the fact that in the model of the signal 𝑍

(

𝑡

)

as

a set of Gaussians (Fig.1), along with the first

frequency harmonic, which gives the maximum

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

, there appear senior harmonics, which also

give maxima to

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

. In addition, we have the

tachogram with extrasystoles (Fig.1), where time

intervals 𝑅𝑅

between the peaks change significantly

in time. This leads to a complex system of

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

maximal values. We are interested in the position of

the first harmonic, which determines the basic

frequency of the heart rate. Let us formulate an

algorithm for finding 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

for a signal with

ectopic heartbeats. We will consider as ectopic the

interval 𝑅𝑅

preceding the moment 𝑡

of the

heartbeat if the duration between the peaks of

neighboring Gaussians satisfies the condition

𝑅𝑅

<0.65 𝑠 (Shubik & Tikhonenko, 2019)

(Shubik & Tikhonenko, 2019). First, using the known

values of 𝑅𝑅

, we calculate the corresponding local

frequencies 𝑓

=

, where the values of 𝑓

have the

dimension Hz, and the values of 𝑅𝑅

are measured in

seconds. Our first assumption is that in the time

interval close to the ectopic Gaussian peak, the value

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

should be approximately equal to 𝑓

. This

physical principle can be formulated in a simple way.

If there is a short time interval 𝑅𝑅

between

Gaussian peaks, then the first harmonic of such a

signal (the sum of identical Gaussian peaks) cannot

be greater than

1

𝑅𝑅

.

However, if we have a case of several successive

ectopic peaks (near the ectopic peak 𝑅𝑅

=𝑅𝑅

there are other ectopic peaks with small 𝑅𝑅

values),

then the behavior of local frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

will also

depend on the subsequent compensatory pause and

neighboring ectopic intervals. Therefore, the

algorithm to determine 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

at 𝑡≈𝑡

must

depend on the neighboring cardiac intervals, that is,

on 𝑅𝑅

,𝑅𝑅

and 𝑅𝑅

,𝑅𝑅

, and,

consequently, on the adjacent moments of time 𝑡

,

𝑡

and 𝑡

,𝑡

. It becomes especially important

when a long compensatory pause followers a short

ectopic interval of extrasystole. The proposed

algorithm to calculate the local frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

should work both for a normal sine rhythm without

ectopic intervals, and for a sequence of Gaussian

peaks with several ectopic intervals 𝑅𝑅

.

Let us consider the limits 𝑓

and 𝑓

for

finding discrete local frequencies on 𝑛 - time interval.

In this case, the upper 𝑓

and lower 𝑓

boundaries of the discrete local frequencies 𝑓

=

can be determined from the relations

𝑓

=

1+𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

𝑓

, (3)

𝑓

=

(

1−𝐴

)

𝑓

. (4)

Note that the upper limit of the frequency search

corridor 𝑓

depends on 𝑅𝑅

measured in seconds.

The formula for 𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

, which is the relative excess

of 𝑓

over the value of 𝑓

, was derived while

analyzing the ectopic intervals given in (Shubik &

Tikhonenko, 2019). The lower limit 𝐴 of the search

for 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

, which characterizes the difference

between 𝑓

and 𝑓

in (4), is a constant value 𝐴=

0.25.

𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

=𝐵

+

, (5)

where 𝑅𝑅

is measured in s, 𝐵

=0.001; 𝐵

ах

=0.21;

𝑅𝑅

=0.840 s, 𝜏

=0.12 s.

The given numerical data were obtained from the

analysis of approximately 70 tachogram records with

various cardiac dysfunctions (Shubik & Tikhonenko,

2019).

For short (extrasystolic) time intervals 𝑅𝑅

≈

0.4 𝑠, the excess 𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

of the discrete 𝑓

over

𝑓

has a small value 𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

<<1. For long time

intervals 𝑅𝑅

≫1.4 𝑠, the value of 𝐵

(

𝑅𝑅

)

reaches

its asymptotic value 𝐵

ах

=0.21. Thus, at 𝑅𝑅

≤

𝑅𝑅

, the upper search limit 𝑓

for the continuous

function 𝑓

(

𝑡

)

slightly exceeds the discrete

frequency 𝑓

=

. For such intervals 𝑓

=

1.001𝑓

. For intervals with 𝑅𝑅

>1.4 𝑠, the

discrete upper search boundary tends to 𝑓

=

1.21𝑓

. Note that after the ectopic interval

𝑅𝑅

=

𝑅𝑅

= 0.401 𝑠 with number 𝑛, we observe long

compensatory pause 𝑅𝑅

= 1.284 𝑠 with number

𝑛+1. As a result, the ratio of adjacent local

frequencies will also be large

=

≈3.2.

Consequently, the constant A, which determines the

lower search limit for the local frequency, should be

increased to the value 𝐴=0.7.

Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated Signals

1041

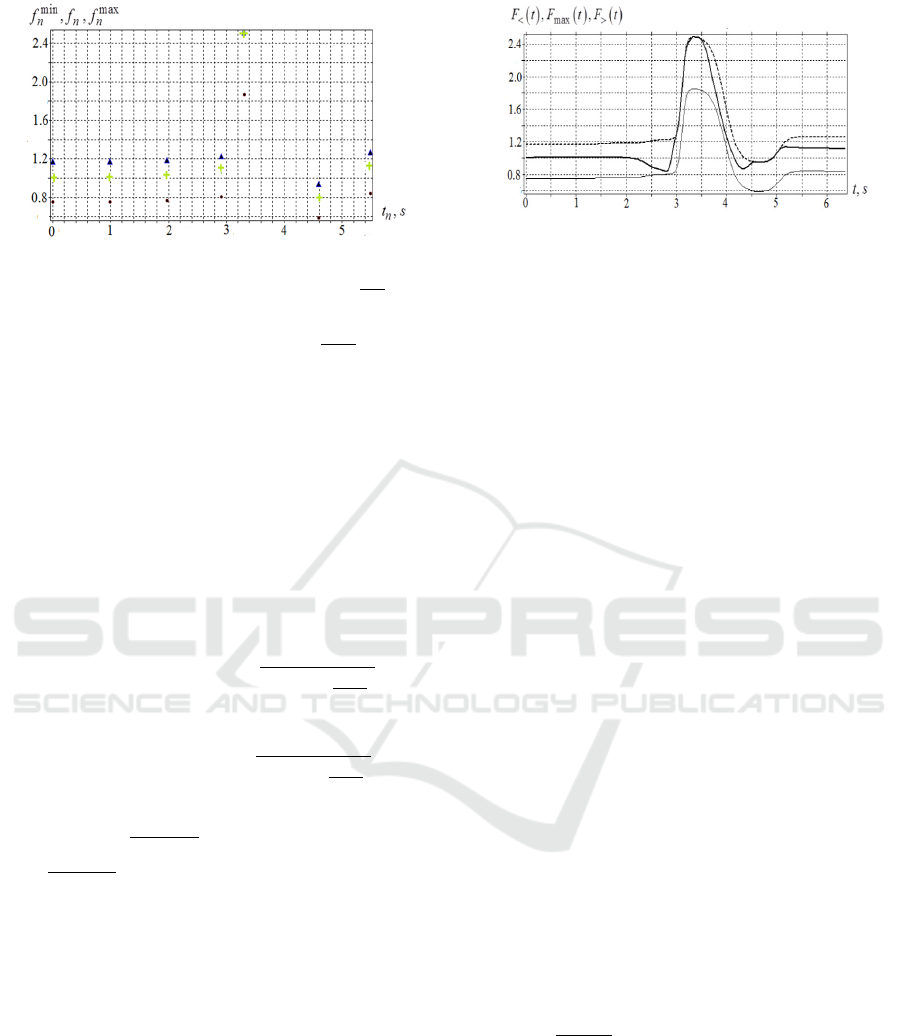

Figure 3: Time dependence of discrete local frequencies for

𝑅𝑅

tachogram: 𝑓

are indicated by dots, 𝑓

=

− by

crosses, 𝑓

− by triangles. For 𝑡=𝑡

= 3.31 𝑠 (the

moment of ectopic heartbeat) 𝑓

=𝑓

=

.

Fig.3 shows the discrete local frequencies for the

sequence of cardio intervals in the 𝑅𝑅

record.

The next task is to find new smooth boundaries

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

and 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

depending on time continuously in

the interval 0 ≤ 𝑡 ≤ 𝑇 (𝑇 is the observation period

for the signal), based on 𝑓

and 𝑓

frequencies

specified for discrete 𝑛. The required formulas for

upper 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

and lower 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

continuous boundaries

of the local frequency have the form of sigmoid

functions

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

=𝑓

+

∑

,

(6)

𝐹

(

𝑡

)

=𝑓

+

∑

, (7)

where 𝑡

=

(

)

is the center of the interval;

𝜏

=

(

)

=𝑅𝑅

/10 is the characteristic time

depending on the duration of the interval between

heartbeats. If the time interval ends with extrasystole

𝑅𝑅

= 0.401 𝑠, then the characteristic time 𝜏

will

be small 𝜏

≈ 0.04 𝑠. If the time interval ends with

compensatory pause 𝑅𝑅

= 1.284 𝑠, then the

transition region will be large 𝜏

≈0.13 𝑠.

Approximation by smooth sigmoid functions has

an advantage over approximations using splines. In

the case of strong heterogeneity in the position of

discrete points, spline approximation leads to strong

oscillation of a smooth curve for intermediate values

of the argument.

Figure 4: Dependence on time of the lower limit of

frequency search 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(thin line), the sought local

frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(thick line), and the upper limit of

frequency search 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(dashed line) for tachogram 𝑅𝑅

The final step is to determine 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

by finding

the maximum of

|

𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)|

(CWT of frequency

modulated signal 𝑍(𝑡)). Fig.4 shows the frequency

corridor 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

≤𝐹

(

𝑡

)

≤𝐹

(

𝑡

)

for local

(instantaneous) frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

in the case of a

single extrasystole 𝑅𝑅

= 0.401 𝑠 with

compensatory pause 𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

= 1284 𝑚𝑠.

2.3 Algorithm for Calculating Local

Frequency in the Case of a

Tachogram with Three

Extrasystoles

Let us apply the algorithm to determine 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

in

the case of tachograms with multiple ectopic

intervals. As an example, we consider the tachogram

record 𝑅𝑅

= {1072, 544, 1056, 552, 1124, 548,

1129} with three extrasystoles:

𝑅𝑅

(

1

)

=

544 𝑚𝑠

,

𝑅𝑅

(

2

)

= 552 𝑚𝑠,

𝑅𝑅

(

3

)

= 548 𝑚𝑠

given in (Shubik & Tikhonenko, 2019). Each of the

extrasystoles is followed by the compensatory pause.

The processing sequence of such a tachogram

𝑅𝑅

is similar to the example of the tachogram

𝑅𝑅

discussed above. The analysis of |𝑉

(

𝜈,𝑡

)

| (CWT

for the tachogram 𝑅𝑅

) shows the existence of three

vertices 𝑖=3 located at points with specific fixed

frequencies and times

𝜈

(

𝑖

)

,𝑡

(

𝑖

)

, measured in

Hz and s, respectively. These vertices relate to the

extrasystoles with the characteristic frequency

𝜈

(

𝑖

)

=

(

)

.

Here we have {𝜈

(

1

)

= 1.838 𝐻𝑧, 𝑡

(

1

)

=

1.616 𝑠}; {𝜈

(

2

)

= 1.811 𝐻𝑧, 𝑡

(

2

)

=

3.224 𝑠}; {𝜈

(

3

)

= 1.825 𝐻𝑧, 𝑡

(

3

)

=

4.896 𝑠}.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

1042

Figure 5: Dependence on time of the lower limit of

frequency search 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(thin line), the sought local

frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(thick line), and the upper limit of

frequency search 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

(dashed line) for tachogram 𝑅𝑅

.

The a

nalysis of Fig.5 reveals a sharp increase in

the sought local frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

at the moments of

extrasystoles for the 𝑅𝑅

tachogram with three

extrasystoles, and then a decrease during the

subsequent compensatory pauses. Three maxima of

the continuous function 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

exactly correspond

to the discrete values

𝜈

(

𝑖

)

,𝑡

(

𝑖

)

. Based on the

processing of the data taken from (Shubik &

Tikhonenko, 2019), we can conclude that each

individual extrasystole, characterized by its own

interval and compensatory pause, differs from

another extrasystole in the duration and the range of

oscillations of the corresponding local frequency

function. Thus, the time behavior of local frequency

near extrasystoles is closely related to the properties

of extrasystoles. This fact can serve as a basis for

classifying ectopic beats.

3 DISCUSSION

For many functional tests (bicycle ergometry,

treadmill, orthostatic, respiratory, glucose-tolerant,

pharmacological, and psychoemotional tests) the

quantitative description of non-stationary heart rate

variability (HRV) is of great importance. The non-

stationary nature of HRV is reflected in the

significant dependence of spectral and statistical

properties of the processed signals on time. It is

especially difficult to process HRV signals with

extrasystoles - premature contractions of the heart, in

which the local (instantaneous) frequency of the

signal changes by 3-4 times over a time interval of

𝑅𝑅

≈0.5 𝑠. As a basis for the analysis of HRV

with extrasystoles, this paper uses frequency-

modulated signal model (FMS) instead of the

traditional amplitude-modulated signal model

(AMS). AMS tachogram model (Electrophysiology,

1996) assumes that peaks of different heights 𝑅𝑅

are

uniformly located at a time grid, and separated by

equal time intervals ∆𝑡 = 𝑅𝑅𝑁𝑁, where the

𝑅𝑅𝑁𝑁 value is the average duration of 𝑅𝑅

intervals

over the entire observation period. Frequency

modulated signal (FMS) is a set of identical Gaussian

peaks whose centers are located on an uneven time

grid and coincide in time with the true moments of

heartbeats 𝑡

=𝑡

+𝑅𝑅

,𝑛=0,1,2,…𝑁−1,

𝑁 is the number of heartbeats. In contrast to AMS

model, FMS model used in the article makes it

possible to find the true frequencies of heart rate

oscillations. The differences between traditional

AMS model and FMS model are especially noticeable

when analyzing functional tests, in which the

tachogram trend is clearly visible over the entire

testing period

In this paper, we propose to analyze the time

behavior of local (instantaneous) frequency 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

as a new characteristic of the heart rhythm with strong

non-stationarity (arrhythmia, extrasystole). The

behavior in time of the continuous signal 𝐹

(

𝑡

)

shows both the presence of extrasystoles and their

difference from each other.

An essential advantage of this approach is in the

fact that FMS model allows us to obtain an analytical

expression for the continuous wavelet transform

(CWT) with the Morlet mother wavelet function. The

analytical expression for the wavelet spectrum allows

for the efficient calculation and analysis of the local

frequency function.

The advantage of considering local frequency as a

new characteristic of the tachogram becomes relevant

when studying various cardiac arrhythmias. In this

case the normal sinus rhythm is disrupted and the true

moments of cardiac contractions become important.

An important application of the method proposed in

this article is the study of single and repeated

extrasystoles associated with the appearance of an

ectopic focus of trigger activity, as well as with the

existence of a repeated reverse excitation entry (re-

entry mechanism). The behavior of local frequency

function over time is different for different types of

ectopic beats. Therefore, this characteristic can serve

as a basis for classifying arrhythmias.

The main

prognostic parameters for HRT are: TO - the onset of

extrasystole and TS - the extrasystole slope, which do

not take into account the extrasystoles themselves and

subsequent compensatory pauses, namely 𝑅𝑅

and

𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

intervals. We believe that the study of HRT

should include the intervals of the extrasystole and

the compensatory intervals, as they contain important

information about the characteristic features of the

rhythm disturbance.

Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated Signals

1043

4 CONCLUSIONS

The article proposes a mathematical model in which

the tachogram signal is considered as FMS

(frequency-modulated signal), which is a

superposition of identical Gaussian peaks. The

maxima of the Gaussian peaks are located at the

moments of real heart contractions. To study HRT

(heart rate turbulence), both the durations of the

ectopic intervals between the peaks 𝑅𝑅

and the

duration of the subsequent compensatory pauses

𝑅𝑅

(

0

)

are taken into account.

For quantitative analysis of HRT, we propose to

calculate the time behavior of local frequency

𝐹

(𝑡) at any time both before and after ectopic

beats. This allows us to classify the ectopic intervals

and subsequent compensatory pauses. In the change

of 𝐹

(𝑡), one can identify a trend, as well as

fluctuations relative to this trend.

The proposed method based on the analysis of

local heart rate can be applied to study non-stationary

cardiac tachograms of various patients with normal

sinus rhythm both at rest and during functional tests.

We can also propose to use the developed method for

classification of cardiac rhythm with ectopic intervals

for patients suffering from congestive heart failure

(CHF), atrial fibrillation (AF), atrial premature

contraction (APC), ventricular premature contraction

(VPC), left bundle branch block (LBBB),

ischemic/dilated cardiomyopathy (ISCH) and sick

sinus syndrome (SSS).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research is funded by the Ministry of Science and

Higher Education of the Russian Federation as part of

the World-class Research Center program: Advanced

Digital Technologies (contract No. 075-15-2022-311

dated 20.04.2022)

REFERENCES

Schmidt, G., Malik, M., Barthel, P., Schneider, R., Ulm, K.,

Rolnitzky, L., ... & Schömig, A. (1999). Heart-rate

turbulence after ventricular premature beats as a

predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction.

The Lancet, 353(9162), 1390-1396.

Bauer, A., Malik, M., Schmidt, G., Barthel, P., Bonnemeier,

H., Cygankiewicz, I., ... & Zareba, W. (2008). Heart

rate turbulence: standards of measurement,

physiological interpretation, and clinical use:

International Society for Holter and Noninvasive

Electrophysiology Consensus. Journal of the American

College of Cardiology, 52(17), 1353-1365.

Disertori, M., Masè, M., Rigoni, M., Nollo, G., & Ravelli,

F. (2016). Heart rate turbulence is a powerful predictor

of cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmias in

postmyocardial infarction and heart failure patients: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation:

Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, 9(12), e004610.

MA, W. (2004). Heart rate turbulence: a 5-year review.

Heart Rhythm, 1, 732-738.

Cygankiewicz, I., & Zaręba, W. (2006). Heart rate

turbulence-an overview of methods and applications.

Cardiology Journal, 13(5), 359-368.

Cygankiewicz, I. (2013). Heart rate turbulence. Progress in

cardiovascular diseases, 56(2), 160-171.

Germanova, O., Shchukin, Y., Germanov, V., Galati, G., &

Germanov, A. (2021). Extrasystolic arrhythmia: is it an

additional risk factor of atherosclerosis? Minerva

Cardiology and Angiology, 70(1), 32-39.

Huikuri, H. V., Castellanos, A., & Myerburg, R. J. (2001).

Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. New England

Journal of Medicine, 345(20), 1473-1482.

Zeid, S., Buch, G., Velmeden, D., Söhne, J., Schulz, A.,

Schuch, A., ... & Wild, P. S. (2024). Heart rate

variability: Reference values and role for clinical

profile and mortality in individuals with heart failure.

Clinical Research in Cardiology, 113(9), 1317-1330.

Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010).

The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate

variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors.

International journal of cardiology, 141(2), 122-131.

Kubota, Y., Chen, L. Y., Whitsel, E. A., & Folsom, A. R.

(2017). Heart rate variability and lifetime risk of

cardiovascular disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in

Communities Study. Annals of epidemiology, 27(10),

619-625.

Huikuri, H. V., & Stein, P. K. (2013). Heart rate variability

in risk stratification of cardiac patients. Progress in

cardiovascular diseases, 56(2), 153-159.

Turcu, A. M., Ilie, A. C., Ștefăniu, R., Țăranu, S. M., Sandu,

I. A., Alexa-Stratulat, T., ... & Alexa, I. D. (2023). The

impact of heart rate variability monitoring on

preventing severe cardiovascular events. Diagnostics,

13(14), 2382.

Yan, S. P., Song, X., Wei, L., Gong, Y. S., Hu, H. Y., & Li,

Y. Q. (2023). Performance of heart rate adjusted heart

rate variability for risk stratification of sudden cardiac

death. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 23(1), 144.

Lombardi, F., & Stein, P. K. (2011). Origin of heart rate

variability and turbulence: an appraisal of autonomic

modulation of cardiovascular function. Frontiers in

Physiology, 2, 95.

Blesius, V., Schölzel, C., Ernst, G., & Dominik, A. (2020).

HRT assessment reviewed: a systematic review of heart

rate turbulence methodology. Physiological

Measurement, 41(8), 08TR01.

Rajendra Acharya, U., Paul Joseph, K., Kannathal, N., Lim,

C. M., & Suri, J. S. (2006). Heart rate variability: a

review. Medical and biological engineering and

computing, 44, 1031-1051.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

1044

Sauerbier, F., Haerting, J., Sedding, D., Mikolajczyk, R.,

Werdan, K., Nuding, S., ... & Kluttig, A. (2024). Impact

of QRS misclassifications on heart-rate-variability

parameters (results from the CARLA cohort study).

PloS one, 19(6), e0304893.

Yin, D. C., Wang, Z. J., Guo, S., Xie, H. Y., Sun, L., Feng,

W., ... & Qu, X. F. (2014). Prognostic significance of

heart rate turbulence parameters in patients with chronic

heart failure. BMC cardiovascular disorders, 14, 1-8.

Koyama, J., Watanabe, J., Yamada, A., Koseki, Y., Konno,

Y., Toda, S., ... & Shirato, K. (2002). Evaluation of

heart-rate turbulence as a new prognostic marker in

patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation journal,

66(10), 902-907.

Tsvetnikova, A.A., Bernhard,t E.R., Parmon, E.V., Aseev,

A.V., Treshkur, T.V.. (2008). Turbulentnost’

serdechnogo ritma: metodicheskie aspekty (Inkart,

SPb.) (in Russian).

Electrophysiology, T. F. O. T. E. S. O. C. T. N. A. S. O. P.

(1996). Heart rate variability: standards of

measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical

use. Circulation, 93(5), 1043-1065.

Milaras, N., Dourvas, P., Doundoulakis, I., Sotiriou, Z.,

Nevras, V., Xintarakou, A., ... & Gatzoulis, K. (2023).

Noninvasive electrocardiographic risk factors for

sudden cardiac death in dilated cardiomyopathy: is

ambulatory electrocardiography still relevant? Heart

Failure Reviews, 28(4), 865-878.

Bozhokin, S. V., Suslova, I. B. (2014). Analysis of non-

stationary HRV as a frequency modulated signal by

double continuous wavelet transformation method.

Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 10, 34-40.

Bozhokin, S. V., Lesova, E. M., Samoilov, V. O.,

Tolkachev, P. I., (2012) Wavelet Analysis of

Nonstationary Heart Rate Variability in a Head-Up Tilt-

Table Test, Biophysics, 57(4), 530-543.

Bozhokin, S. V., Lesova, E. M., Samoilov, V. O., &

Barantsev, K. A. (2020). Nonstationary heart rate

variability during the head-down tilt test. Biophysics,

65, 151-158.

Bozhokin S. V., Lesova E. M., Samoilov V. O., Tarakanov

D. E. (2018) Nonstationary heart rate variability in

respiratory tests, Human Physiology, 44(1), 32-40.

Addison, P. S. (2005). Wavelet transforms and the ECG: a

review. Physiological measurement, 26(5), R155.

Cartas-Rosado, R., Becerra-Luna, B., Martínez-Memije,

R., Infante-Vazquez, O., Lerma, C., Perez-Grovas, H.,

& Rodríguez-Chagolla, J. M. (2020). Continuous

wavelet transform based processing for estimating the

power spectrum content of heart rate variability during

hemodiafiltration. Biomedical Signal Processing and

Control, 62, 102031.

Wang, T., Lu, C., Sun, Y., Yang, M., Liu, C., & Ou, C.

(2021). Automatic ECG classification using continuous

wavelet transform and convolutional neural network.

Entropy, 23(1), 119.

Shubik, Yu.V., Tikhonenko, V.M. (2019). Holter

monitoring for arrhythmia. Kholterovskoe

monitorirovanie pri aritmiyakh. OOO”Nevskij rakurs“,

Saint-Petersburg,(in Russian).

Heart Rate Turbulence: Wavelet Analysis of Frequency Modulated Signals

1045