Investigation of the Relational Strength Between Suspected Atrial

Fibrillation Triggers and Detector-Based Arrhythmia Episode

Occurrence

Vilma Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e

1 a

and Andrius Petr

˙

enas

1,2 b

1

Biomedical Engineering Institute, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, Lithuania

2

Faculty of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, Lithuania

{vilma.plusciauskaite, andrius.petrenas}@ktu.lt

Keywords:

Wearables, Remote Monitoring, Relation Assessment, Electrocardiogram, Photoplethysmogram, Arrhythmia

Detection, Personalized Arrhythmia Management.

Abstract:

Atrial fibrillation (AF) treatment remains challenging, with current options often limited to anticoagulants

and antiarrhythmic medications. Growing evidence suggests that acute exposures, referred to as AF triggers,

can initiate AF in some patients. Therefore, identifying and managing personal triggers may serve as an

effective strategy to complement conventional treatment. This study explores the utility of wearable-based

biosignals to assess the relational strength between the suspected triggers and AF occurrence when episodes

are detected using electrocardiogram (ECG) and photoplethysmogram (PPG). Biosignals from 33 patients

with paroxysmal AF (mean age 61 ± 13 years), who wore an ECG patch and a wrist-worn PPG device

during a 7.0 ± 0.7 day observation period, were used in the study. Suspected triggers due to physical exertion,

psychophysiological stress, and lying on the left side were identified based on a detection parameter calculated

over successive segments of the ECG and/or acceleration signals. The relational strength between a suspected

trigger and AF episodes is quantified based on AF burden, defined as the ratio of time spent in AF to the total

analysis time interval, assuming that the post-trigger AF burden is greater than the pre-trigger AF burden. The

results indicate that the relational strength between suspected triggers and AF episode occurrence, as detected

using ECG- and PPG-based AF detectors, differs from manual annotation by an average of 0.03±0.15 and

-0.21±0.21, respectively. This study demonstrates the potential of wearable-based biosignals in providing

personalized identification of suspected AF triggers. However, challenges such as non-wear periods and poor

PPG signal quality remain to be addressed for practical applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

The management of atrial fibrillation (AF) remains

a complex challenge (Lippi et al., 2021), with treat-

ment options often limited to anticoagulants and an-

tiarrhythmic medications, carrying serious side ef-

fects (Mani and Lindhoff-Last, 2014). Since acute ex-

posures, referred to as AF triggers, may initiate AF in

some patients (Hansson et al., 2004; Groh et al., 2019;

Severino et al., 2019), an effective approach could

involve addressing lifestyle and risk factors together

with conventional treatment (Chung et al., 2020).

Identifying triggers on a patient-specific basis

could become a key component of personalized AF

management, allowing clinicians to address the root

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2949-912X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5700-7196

causes of AF episodes in individual cases. Mean-

while, patients could take an active role in managing

their AF through targeted lifestyle adjustments.

Among suspected AF triggers (Hansson et al.,

2004; Groh et al., 2019), alcohol has been the most

extensively studied, with consistent evidence link-

ing to the onset of AF episodes (Marcus et al.,

2022). Other triggers associated with the occurrence

of AF episodes include physical exertion (Abdulla

and Nielsen, 2009; Guasch and Mont, 2017), lying on

the left side (Gottlieb et al., 2021), and psychophysi-

ological stress (Leo et al., 2023).

A major limitation of previous studies is their re-

liance on self-reported AF triggers, typically gathered

through questionnaires (Hansson et al., 2004; Groh

et al., 2019; Marcus et al., 2022), which are suscep-

tible to bias. For instance, patients often identified

multiple triggers (Groh et al., 2019), suggesting con-

Pluš

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e, V. and Petr

˙

enas, A.

Investigation of the Relational Strength Between Suspected Atrial Fibrillation Triggers and Detector-Based Arrhythmia Episode Occurrence.

DOI: 10.5220/0013343000003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 805-810

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

805

firmation bias, while others may have been reluctant

to disclose certain triggers, such as those related to

unhealthy behaviors.

With advancements in technology, wearable de-

vices are now equipped with biosensors capable of

acquiring various biosignals, potentially enabling the

detection of AF triggers and self-terminating AF

episodes using the same device. In our previous work,

we introduced and examined an approach to quantify-

ing the relation between suspected triggers detected

in long-term biosignals and the occurrence of AF

episodes (Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e et al., 2024a; Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e

et al., 2024b). The previous study demonstrated the

potential of the proposed approach using clinician-

annotated AF episodes. However, applying this in

a clinical practice is particularly challenging, as an-

notating long-term signals is a time-consuming pro-

cess that requires enormous effort from cardiologists.

Therefore, the present study focuses on the utility

of wearable devices to assess the relational strength

when AF episodes are automatically detected using

electrocardiogram (ECG) and photoplethysmogram

(PPG) biosignals.

2 METHODS

2.1 Database

One hundred eighty-two patients diagnosed with

paroxysmal AF were recruited from the Cardiol-

ogy Department at Vilnius University Hospital San-

taros Klinikos. Only those who experienced at

least one AF episode during the observation period

(7.0 ± 0.7 days) were included, resulting in a sub-

set of 33 patients (19 women) with a mean age of

61 ± 13 years. The study was approved by the Vil-

nius Regional Bioethics Committee (reference num-

ber 158200-18/7-1052-557). All patients provided

written informed consent before participation in the

study and were fully informed of the research objec-

tives and procedures.

The database includes biosignals acquired dur-

ing daily activities using a Bittium OmegaSnap™

one-channel ECG patch (Bittium, Finland) and a

wrist-worn device developed at the Biomedical En-

gineering Institute of Kaunas University of Technol-

ogy (Bacevi

ˇ

cius et al., 2022). The ECG patch, po-

sitioned directly on the sternum, acquired continuous

ECG at 500 Hz and tri-axial acceleration signals at

25 Hz, while the wrist-worn device acquired contin-

uous PPG at 100 Hz. AF episodes were annotated

by cardiology residents who reviewed the long-term

ECGs and consulted an experienced cardiologist in

uncertain cases. The biosignal database can be ac-

cessed on Zenodo (Bacevi

ˇ

cius et al., 2024).

2.2 Detection of AF Episodes

Two detectors are used to detect AF episodes: one

based on the analysis of the ECG (Petr

˙

enas et al.,

2015) and the other on the PPG (Solo

ˇ

senko et al.,

2019). Both detectors rely on the irregularity of beat-

to-beat intervals and elevated heart rate during AF.

Additionally, the detectors include blocks for ectopic

beat removal and suppression of bigeminy and sinus

arrhythmia to reduce the number of false positives.

The PPG-based AF detector also incorporates sig-

nal quality assessment to ensure that detection is not

performed on low-quality pulses, whereas the ECG-

based detector does not include signal quality assess-

ment. Both detectors are configured to detect AF

episodes as short as 60 beats.

2.3 Detection of Suspected Triggers

The detection of suspected triggers in biosignals is

explained in detail in (Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e et al., 2024b).

Each type of suspected trigger, ie., physical exertion,

psychophysiological stress, and lying on the left side,

is detected based on a detection parameter calculated

over successive segments of the ECG and/or acceler-

ation signals, producing a time series that undergoes

threshold-based detection.

Poor-quality ECG segments were excluded based

on the bsqi index, which assesses the agreement of

two QRS detectors (Behar et al., 2013), with an agree-

ment threshold of 90%. Only segments free of prema-

ture atrial contractions, atrial flutter, and atrial tachy-

cardia were considered for analysis.

Physical exertion is detected using the metabolic

equivalent of task (MET), a measure of energy ex-

penditure relative to the resting metabolic rate. The

METs are estimated from acceleration and heart

rate, accounting for patient-specific variability using

a regression equation derived in (Moeyersons et al.,

2019). A suspected trigger due to physical exertion is

detected if the mean MET, computed over 1-minute

intervals with non-AF rhythm, exceeds 5 METs.

Psychophysiological stress is detected when heart

rate suddenly increases by more than 15 beats per

minute within a 1-minute interval, excluding eleva-

tions due to physical activity or arrhythmia (Brouwer

and Hogervorst, 2014). Physical activity is consid-

ered absent or negligible if the average mean absolute

deviation of the tri-axial raw acceleration signal in the

5-minute segment before and during the analyzed 1-

minute interval is below 22.5 mg (milligravity), indi-

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

806

cating sedentary behavior such as sitting or standing

still (V

¨

ah

¨

a-Ypy

¨

a et al., 2018).

Lying on the left side is detected when the medio-

lateral axis acceleration signal stays below −600 mg

for at least 1 hour. Since position changes may oc-

cur frequently during the night, only the first detected

trigger within the preceding 4 hours is considered.

2.4 Quantification of the Relational

Strength

The primary assumption for identifying a trigger is

that the actual trigger for a particular patient will in-

crease the AF burden B, defined as the ratio of time

the patient spends in AF relative to the total observa-

tion period.

The relational strength between suspected trig-

gers and AF episode occurrence in individual pa-

tients is assessed based on a cumulative princi-

ple (Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e et al., 2024a), summing the events

where the post-trigger AF burden B

1,n

is greater than

the pre-trigger AF burden B

0,n

. The reason for invok-

ing the cumulative principle is based on the fact that it

is unlikely a trigger will consistently influence B, even

if a patient is prone to that particular trigger. Instead,

triggers are more likely to contribute to the sporadic

initiation of AF due to their interaction with the ar-

rhythmogenic substrate and modulating factors (Vin-

centi et al., 2006; Nattel and Dobrev, 2016; Severino

et al., 2019). The relational strength γ is quantified as

follows (Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e et al., 2024a):

γ =

N

t

∑

n=1

B

1,n

1 + B

0,n

H(B

1,n

− B

0,n

), (1)

where N

t

represents the number of suspected triggers

during the observation period, n is the number of de-

tected suspected triggers, and H(·) is the Heaviside

step function. The analysis time interval T , used to

compute B

1,n

and B

0,n

, is set to 4 hours (Marcus et al.,

2021). The relational strength computed for anno-

tated and detector-based AF episode occurrences is

denoted as γ

a

and γ

d

, respectively.

3 RESULTS

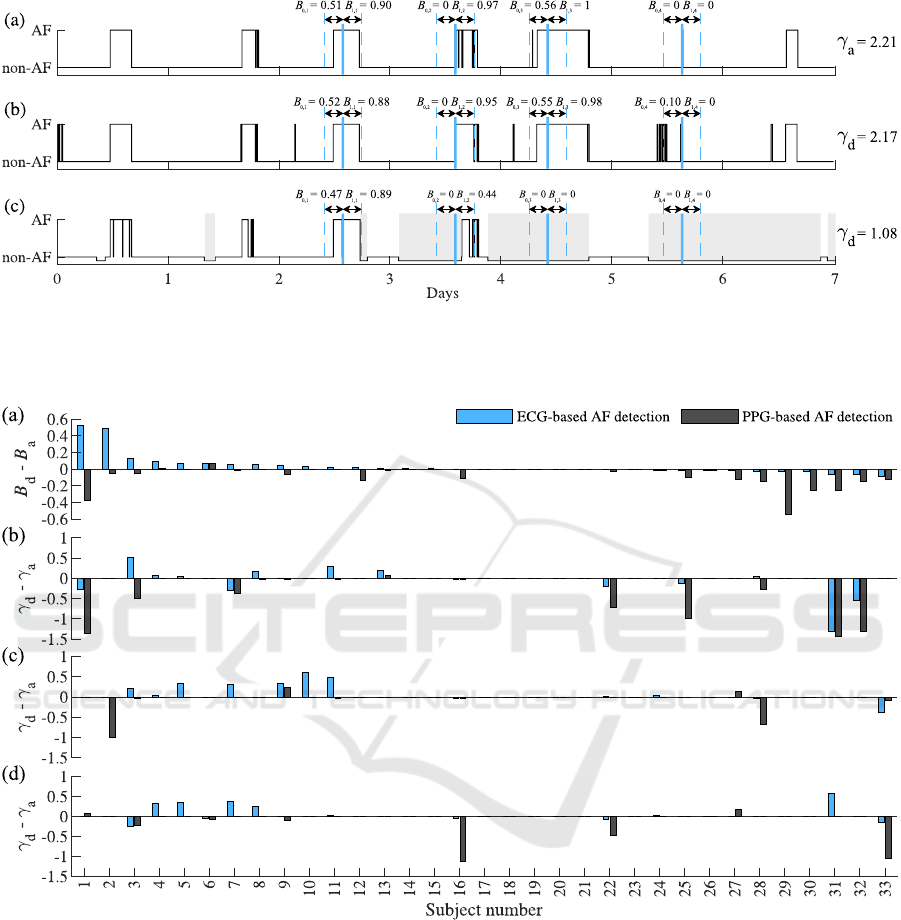

Fig. 1 illustrates the annotated occurrence of episodes

in a patient with paroxysmal AF, along with episodes

detected using ECG- and PPG-based AF detectors,

and their effect on the relational strength. For this par-

ticular example, lying on the left side is only shown,

which was detected four times over a 7-day observa-

tion period. For an annotated AF episode occurrence,

the relational strength γ is 2.21, suggesting a strong

relation between the suspected trigger and increased

post-trigger B. Short-duration false positives from

the ECG-based AF detector increase the pre-trigger

AF burden B

0

, causing a slight decrease in the re-

lational strength (γ = 2.17). Conversely, poor PPG

signal quality and non-wear time of a wrist-worn de-

vice affect both the pre-trigger B

0

and post-trigger B

1

burdens, leading to a substantial reduction in the rela-

tional strength (γ = 1.08).

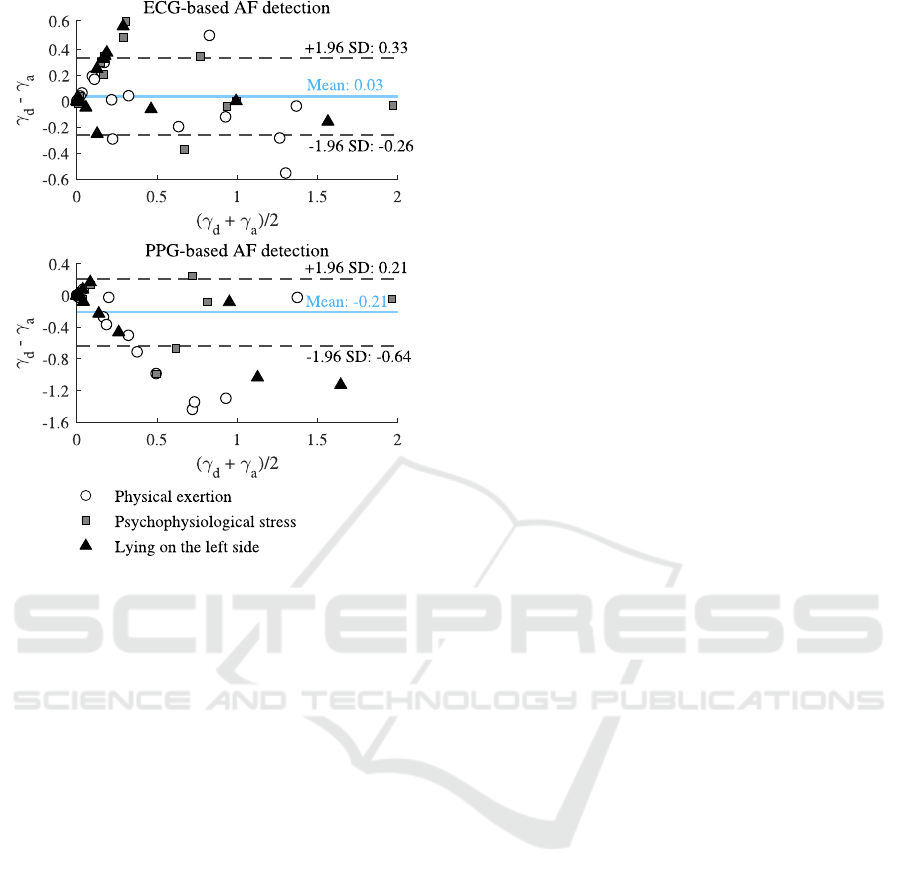

To provide further insight into the impact of AF

episode detection errors on the relational strength,

Fig. 2 shows how changes in B affect γ. The results in-

dicate that an increase in B, caused by falsely detected

AF episodes from the ECG-based detector, tends to

increase γ. This tendency is observed across all types

of suspected triggers. Conversely, due to non-wear

time, PPG-based detection almost always results in a

lower B, which leads to a decrease in γ.

Figure 3 illustrates the error in the relational

strength computed for detector-based and annotated

AF episodes. The results show that PPG-based

AF detection results in a markedly underestimated γ

(mean = -0.21), while the error for ECG-based AF

detection is low (mean = -0.03).

4 DISCUSSION

Considering the practical applicability of the pro-

posed approach for detecting AF triggers in biosig-

nals, it is unrealistic to rely on manually annotated

occurrences of AF episodes for every patient; thus,

automated AF detection becomes essential. To ad-

dress this, we examined both a chest ECG patch and

a wrist-worn device capable of acquiring PPG sig-

nals. Since reliable detection of AF episodes re-

quires long-term monitoring and robust AF detec-

tors (Butkuvien

˙

e et al., 2024), understanding how de-

tection errors affect episode occurrence – and, in turn,

relational strength – is a crucial area of investigation.

The main finding of the study is that misdetec-

tions and non-wear periods considerably reduce the

relational strength between suspected triggers and AF

episode occurrence. However, the limitations of AF

detectors do not render the proposed method imprac-

tical, due to the cumulative principle used in calcu-

lating relational strength. This principle ensures that

the relational strength increases as the number of sus-

pected triggers grows, indicating that a longer obser-

vation period is needed to achieve the same effect on

γ. While clinical studies are still needed to determine

how γ should be interpreted, we suggest using γ val-

ues greater than 1.5 as a starting point for considering

Investigation of the Relational Strength Between Suspected Atrial Fibrillation Triggers and Detector-Based Arrhythmia Episode Occurrence

807

Figure 1: Illustration of the relational strength γ for AF episodes identified by (a) annotation, (b) ECG-based detection, and (c)

PPG-based detection. The onsets of a suspected trigger, attributed to lying on the left side, are shown in blue. Grey rectangles

indicate periods of non-wear or poor PPG quality. Note that the ECG-based AF detector prioritizes sensitivity, resulting in

more false positives, while the PPG-based detector emphasizes specificity, leading to missed or truncated episodes.

Figure 2: (a) The difference in AF burden B between annotated episodes and those detected using ECG- and PPG-based AF

detection, along with its impact on the difference in relational strength γ for suspected triggers of (b) physical exertion, (c)

psychophysiological stress, and (d) lying on the left side. Subjects are arranged in descending order based on the difference

in B observed with ECG-based detection.

a suspected trigger as an actual trigger (Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e

et al., 2024a). A γ value above 1.5 can be indicative

of a strong relation, as achieving such a value requires

at least two suspected triggers for which B

1,n

is much

greater than B

0,n

.

Understanding how triggers affect AF episodes

in individual patients remains an unresolved ques-

tion. In this study, we focused on three suspected

triggers based on their relations with AF occurrence

and their feasibility for detection in biosignals. High-

intensity exercise is a known trigger for AF episodes,

both in athletes and the general population (Sham-

loo et al., 2018). Psychophysiological stress releases

stress hormones, elevating heart rate and cardiac con-

tractions, which may also trigger AF (Leo et al.,

2023). Meanwhile, the left lying position is com-

monly self-reported as an AF trigger (Groh et al.,

2019), likely due to increased pressure on the atrial

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

808

Figure 3: The error in relational strength computed for

detector-based and annotated AF episodes across different

types of suspected triggers.

walls and pulmonary veins (Gottlieb et al., 2021; Got-

tlieb et al., 2023). In our previous work, we also in-

vestigated sleep disturbances as a suspected trigger,

quantified by the standard deviation of beat-to-beat

intervals, which serves as an indicator of the domi-

nant sympathetic and vagal activity components (Ma-

lik and Camm, 2004). However, we did not include

sleep disorders in this study due to the lack of differ-

ence when compared to the control γ.

The study has several limitations. Within the ini-

tial cohort of patients diagnosed with paroxysmal AF,

only 18% experienced at least one AF episode dur-

ing the one-week observation period. Consequently,

the findings, based on this relatively small dataset,

should be interpreted with caution. Another limita-

tion lies in the lack of a reference for triggers, leav-

ing it unclear whether the detected suspected triggers

were actual triggers. While lying on the left side can

be reliably detected when a chest sensor is used, vali-

dating physical exertion or psychophysiological stress

is more challenging. These triggers are mostly sub-

jective and may not consistently align with the effects

observed in biosignals.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This paper explores the potential of long-term ECG-

and PPG-based monitoring to identify suspected trig-

gers of AF episodes in patients with paroxysmal AF.

The relational strength between suspected triggers

and AF episode occurrences, as detected by ECG- and

PPG-based AF detectors, differs from manual anno-

tation by an average of 0.03 and -0.21, respectively.

While wearable biosignals show promise for person-

alized identification of suspected AF triggers, chal-

lenges such as non-wear periods and poor PPG signal

quality must be addressed to enable clinical applica-

tion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Research Council of

Lithuania under Agreement No. S-MIP-24-73.

REFERENCES

Abdulla, J. and Nielsen, J. R. (2009). Is the risk of atrial

fibrillation higher in athletes than in the general pop-

ulation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eu-

ropace, 11(9):1156–1159.

Bacevi

ˇ

cius, J., Abramikas,

ˇ

Z., Dvinelis, E., Audzijonien

˙

e,

D., Petrylait

˙

e, M., Marinskien

˙

e, J., Staigyt

˙

e, J.,

Karu

ˇ

zas, A., Juknevi

ˇ

cius, V., Jakait

˙

e, R., Basyt

˙

e-

Bacevi

ˇ

c

˙

e, V., Bilei

ˇ

sien

˙

e, N., Solo

ˇ

senko, A., Sokas, D.,

Petr

˙

enas, A., Butkuvien

˙

e, M., Paliakait

˙

e, B., Daukan-

tas, S., Rapalis, A., Marinskas, G., Jasi

¯

unas, E.,

Darma, A., Marozas, V., and Aidietis, A. (2022). High

specificity wearable device with photoplethysmogra-

phy and six-lead electrocardiography for atrial fib-

rillation detection challenged by frequent premature

contractions: DoubleCheck-AF. Front. Cardiovasc.

Med., 9.

Bacevi

ˇ

cius, J., Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e, V., Abramikas,

ˇ

Z., Badaras,

I., Butkuvien

˙

e, M., Daukantas, S., Dvinelis, E., Gu-

dauskas, M., Jukna, E., Kiseli

¯

ut

˙

e, M., Kundelis, R.,

Marinskien

˙

e, J., Paliakait

˙

e, B., Petr

˙

enas, A., Petry-

lait

˙

e, M., Pilkien

˙

e, A., Pudinskait

˙

e, G., Radavi

ˇ

cius,

V., Rapalis, A., Sokas, D., Solo

ˇ

senko, A., Staigyt

˙

e, J.,

Stankevi

ˇ

ci

¯

ut

˙

e, G., Taparauskait

˙

e, N., Zarembait

˙

e, G.,

Aidietis, A., and Marozas, V. (2024). Long-term elec-

trocardiogram and wrist-based photoplethysmogram

recordings with annotated atrial fibrillation episodes.

Dataset on Zenodo.

Behar, J., Oster, J., Li, Q., and Clifford, G. D. (2013). ECG

signal quality during arrhythmia and its application

to false alarm reduction. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng.,

60(6):1660–1666.

Brouwer, A.-M. and Hogervorst, M. A. (2014). A new

paradigm to induce mental stress: the Sing-a-Song

Stress Test (SSST). Front. Neurosci., 8:224.

Investigation of the Relational Strength Between Suspected Atrial Fibrillation Triggers and Detector-Based Arrhythmia Episode Occurrence

809

Butkuvien

˙

e, M., Petr

˙

enas, A., Martin-Yebra, A., Marozas,

V., and S

¨

ornmo, L. (2024). Characterization of atrial

fibrillation episode patterns: A comparative study.

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 71(1):106–113.

Chung, M. K., Eckhardt, L. L., Chen, L. Y., Ahmed, H. M.,

Gopinathannair, R., Joglar, J. A., Noseworthy, P. A.,

Pack, Q. R., Sanders, P., Trulock, K. M., et al. (2020).

Lifestyle and risk factor modification for reduction

of atrial fibrillation: A scientific statement from the

American Heart Association. Circ., 141(16):e750–

e772.

Gottlieb, L. A., Coronel, R., and Dekker, L. R. (2023). Re-

duction in atrial and pulmonary vein stretch as a thera-

peutic target for prevention of atrial fibrillation. Heart

Rhythm, 20(2):291–298.

Gottlieb, L. A. et al. (2021). Self-reported onset of parox-

ysmal atrial fibrillation is related to sleeping body po-

sition. Front. Physiol., 12:708650.

Groh, C. A., Faulkner, M., Getabecha, S., Taffe, V., Nah,

G., Sigona, K., McCall, D., Hills, M. T., Sciarappa,

K., Pletcher, M. J., et al. (2019). Patient-reported trig-

gers of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm,

16(7):996–1002.

Guasch, E. and Mont, L. (2017). Diagnosis, pathophysi-

ology, and management of exercise-induced arrhyth-

mias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol., 14(2):88–101.

Hansson, A., Madsen-H

¨

ardig, B., and B. Olsson, S. (2004).

Arrhythmia-provoking factors and symptoms at the

onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a study based

on interviews with 100 patients seeking hospital as-

sistance. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord., 4(1):1–9.

Leo, D. G., Ozdemir, H., Lane, D. A., Lip, G. Y., Keller,

S. S., and Proietti, R. (2023). At the heart of the

matter: How mental stress and negative emotions

affect atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.,

10:1171647.

Lippi, G., Sanchis-Gomar, F., and Cervellin, G. (2021).

Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increas-

ing epidemic and public health challenge. Int. J.

Stroke, 16(2):217–221.

Malik, M. and Camm, A. J. (2004). Autonomic Balance,

chapter 6, pages 48–56. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Mani, H. and Lindhoff-Last, E. (2014). New oral anticoag-

ulants in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation:

a review of pharmacokinetics, safety, efficacy, quality

of life, and cost effectiveness. Drug Des. Devel. Ther.,

pages 789–798.

Marcus, G. M., Modrow, M. F., Schmid, C. H., Sigona, K.,

Nah, G., Yang, J., Chu, T.-C., Joyce, S., Gettabecha,

S., Ogomori, K., et al. (2022). Individualized stud-

ies of triggers of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the I-

STOP-AFib randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol.,

7(2):167–174.

Marcus, G. M., Vittinghoff, E., Whitman, I. R., Joyce, S.,

Yang, V., Nah, G., Gerstenfeld, E. P., Moss, J. D., Lee,

R. J., Lee, B. K., et al. (2021). Acute consumption

of alcohol and discrete atrial fibrillation events. Ann.

Intern. Med., 174(11):1503–1509.

Moeyersons, J., Amoni, M., Van Huffel, S., Willems, R.,

and Varon, C. (2019). R-DECO: An open-source Mat-

lab based graphical user interface for the detection and

correction of R-peaks. Peerj Comput. Sci., 5:e226.

Nattel, S. and Dobrev, D. (2016). Electrophysiological and

molecular mechanisms of paroxysmal atrial fibrilla-

tion. Nat. Rev. Cardiol., 13(10):575–590.

Petr

˙

enas, A., Marozas, V., and S

¨

ornmo, L. (2015). Low-

complexity detection of atrial fibrillation in contin-

uous long-term monitoring. Comput. Biol. Med.,

65:184–191.

Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e, V., Butkuvien

˙

e, M., Rapalis, A., Marozas,

V., S

¨

ornmo, L., and Petr

˙

enas, A. (2024a). An ob-

jective approach to identifying individual atrial fibril-

lation triggers: A simulation study. Biomed. Signal

Process. Control, 87:105369.

Plu

ˇ

s

ˇ

ciauskait

˙

e, V., Solo

ˇ

senko, A., Jan

ˇ

ciulevi

ˇ

ci

¯

ut

˙

e, K.,

Marozas, V., S

¨

ornmo, L., and Petr

˙

enas, A. (2024b).

Assessment of the relational strength between triggers

detected in physiological signals and the occurrence

of atrial fibrillation episodes. Physiological Measure-

ment, 45(9):095011.

Severino, P., Mariani, M. V., Maraone, A., Piro, A., Cec-

cacci, A., Tarsitani, L., Maestrini, V., Mancone, M.,

Lavalle, C., Pasquini, M., et al. (2019). Triggers for

atrial fibrillation: The role of anxiety. Cardiol. Res.

Pract., 2019.

Shamloo, A. S., Arya, A., Dagres, N., and Hindricks, G.

(2018). Exercise and atrial fibrillation: some good

news and some bad news. Galen Med. J., 7:e1401.

Solo

ˇ

senko, A., Petr

˙

enas, A., Paliakait

˙

e, B., S

¨

ornmo, L., and

Marozas, V. (2019). Detection of atrial fibrillation us-

ing a wrist-worn device. Physiol. Meas., 40:025003.

V

¨

ah

¨

a-Ypy

¨

a, H., Husu, P., Suni, J., Vasankari, T., and

Siev

¨

anen, H. (2018). Reliable recognition of lying,

sitting, and standing with a hip-worn accelerometer.

Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports, 28(3):1092–1102.

Vincenti, A., Brambilla, R., Fumagalli, M. G., Merola, R.,

and Pedretti, S. (2006). Onset mechanism of parox-

ysmal atrial fibrillation detected by ambulatory Holter

monitoring. EP Europace, 8(3):204–210.

BIOSIGNALS 2025 - 18th International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

810