Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection

Using the Reflective Play Framework

Julian Marvin Joers

a

and Ernesto William De Luca

b

Human-Centred Design, University Magdeburg, Universit

¨

atsplatz 2, Magdeburg, Germany

Keywords:

Virtual Philosophy Education, Learning of Reasoning, Eudaimonic Learning Environment, Slow Technology.

Abstract:

Since introducing “slow technology” and “reflective informatics” in human-computer interaction (HCI) re-

search, developing prototypes for eudaimonic activities (such as learning and critical thinking) has gained

attention. With ’eudaily’, students are encouraged to reflect on philosophical ideas playfully. Using the frame-

work of reflective play, a database of 22,216 perspectives across 1,507 philosophical ideas, and a measure for

reflective activities in interaction with technology, this prototype was designed and evaluated by 21 students in

an initial use case. Five practical implications to support reflection in HCI can be derived: (1) creating positive

disruption is a design template for disruptions and (2) diversity of perspectives can serve as a design blueprint

for positive disruption. Furthermore, (3) the importance of enabling the customization of the reflective process

and (4) creating a balance between instruction and exploration have been identified. Finally, (5) users demand

a variety of self-expression mechanisms during the interaction.

1 INTRODUCTION

Beyond the doctrine of simplicity or usability in HCI

(Sarkar, 2023), we can create spaces for humans to

engage with profound questions and activities, to fos-

ter deeper self-exploration, and to ’dwell more in this

world’. “Slow Technology” (Halln

¨

as and Redstr

¨

om,

2001) was the first call for an alternative develop-

ment doctrine for technology that does not focus on

task accomplishment but on the creation of space for

reflection and thinking. Perceiving “slow technol-

ogy” remaining “somewhat vague as to what consti-

tutes reflection” (Baumer, 2015, p. 587), Baumer in-

troduced the term “reflective informatics” (Baumer,

2015), i.e. a conceptual formulation of designing for

reflection in HCI. Several applications of these con-

cepts can be found today in a large number of proto-

types that have been published in the last two years

alone (Li et al., 2023; Behzad, 2023; Pasumarthy

et al., 2024; Cremaschi et al., 2024; Sathya and Naka-

gaki, 2024; Kwon et al., 2024; Liedgren et al., 2023).

Betran et al. state: “[...] we argue that, in a world

where technology is increasingly present, functional

and productive; it is equally important to also support

the socio-emotional value of play” (Altarriba Bertran

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8943-6307

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3621-4118

et al., 2020, p. 3). In 2024, Miller et al. developed

the “Design Framework for Reflective Play” (Miller

et al., 2024) presenting a procedural design guideline

for reflective activities in interaction with games. The

ideas of abstract thinking and perspective-taking are

often referred to as eudaimonic habits (Huta, 2016).

Consequently, contributions in HCI often refer to eu-

daimonic perspectives when addressing these activi-

ties (Schrier, 2024; Joers and De Luca, 2024; Mekler

and Hornbæk, 2016). For example, Cole & Gillies

describe the eudaimonic (play) experience as one that

aims to encourage reflection and self-development

of the activity afterward (Cole and Gillies, 2022).

Strengthening these critical thinking skills is an im-

portant component for the development of students

in the 21st century (Soffel, 2016). This use case ap-

plies the new framework for reflective play to foster

the reflective processes of students within a playful

environment. In this context, the prototype ’eudaily’

was developed using a wordplay of eudaimonia and

daily. This use case is the first application of this

novel framework, thus no state of practice does yet

exist. Furthermore, it contains practical implications

for the development of reflection-enhancing interac-

tive systems. ’Eudaily’ is also a contribution to the ex-

isting challenge of fostering eudaimonic activities and

enhancing eudaimonic well-being in HCI (Stephani-

dis et al., 2019). Thus, beyond the mere application

484

Joers, J. M. and William De Luca, E.

Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection Using the Reflective Play Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0013347000003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 484-491

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

of this model, important practical implications can be

deduced in the specific context of technology design

for eudaimonic reflection and eudaimonic well-being.

2 BUILDING EUDAILY

For the conception of ’eudaily’

1

we used a novel

framework for reflective play (Miller et al., 2024),

the design guidelines for slow serious games (Marsh,

2016), and the eudaimonic interaction design princi-

ples (Joers and De Luca, 2024). The design frame-

work for reflective play has five sequential phases:

disruptions, slowdowns, questioning, revisiting, and

enhancers. Design templates are available to the de-

veloper in all process-related design steps to enable

a reflective experience in a game. The aim of this

framework application is not only a reflection during

the interaction (endo-transformation) but also a real

behavior change (exo-transformation). For the devel-

opment of the interaction during the slowdown, the

guidelines for slow serious games were considered.

Marsh defined eleven design guidelines for slow seri-

ous gaming, e.g. avoiding narration and further infor-

mation but creating a space for de-accelerated reflec-

tion (Marsh, 2016). Finally, the eudaimonic interac-

tion design principles call for the reduction of quan-

tification within the interaction, the promotion of the

user flow, and the reduction of informal feedback in-

stead of the gamification of the activity per se (Joers

and De Luca, 2024). These principles were also taken

into account during the development.

The core idea of ’eudaily’ is encouraging students

to reflect on philosophical ideas (e.g. laws of na-

ture, subjective truth, free will, infinity, or love) tak-

ing existing perspectives of philosophers into account.

Accordingly, a database of philosophical perspectives

on topics was used for the development of ’eudaily’.

Through years of preliminary work by Gibson and

Berry, who together maintain the website “Philosophy

Ideas”

2

, we were able to access 22,126 perspectives

on 1,507 topics such as freedom of lifestyle, nature,

and virtue of courage. The students interact playfully

with the existing perspectives on the randomly cho-

sen topic and are supported in his or her eudaimonic

process of reflection. The topic is selected at random

via a web interface and the perspectives are loaded

into ’eudaily’ accordingly. In the following, the exact

course of the interaction is illustrated in detail in the

subsections.

1

http://eudaily.joersi.com/

2

http://www.philosophyideas.com/

2.1 Disruptions

At the beginning of the interaction, the student is

confronted with a random topic and its perspectives

serving as a disruptive moment within ’eudaily’. A

screenshot of the disruptive moment is shown in Fig-

ure 1. In the moment of disruption, we specifi-

cally aim for an uncomfortable, possibly contradic-

tory encounter with perspectives on a philosophical

object, causing a general moment of friction. During

Figure 1: The ’Eudai-Bot’ takes a walk in the rain and re-

flects on the philosophical positions of a construct (phase of

disruption).

the disruptive phase, one “creates an opportunity for

the player to question their own assumptions and re-

evaluate their own systems of thought” (Miller et al.,

2024, p. 5). Thus, the direct confrontation “with the

player in relation to their beliefs and actions” (Miller

et al., 2024, p. 7) has been chosen as a design ap-

proach to create discomfort in the interaction. The

students can change the topic at any time using the re-

fresh button. The perspectives are shown overlapping,

forcing the student to ’solve’ the thought by clicking

on the perspectives and moving on to another state-

ment. Only after all possible thoughts have been re-

solved the student can access the next page by an ac-

tivated next button and thus enter the phase of slow-

down.

2.2 Slowdown

Based on the reflective play framework, it is intended

to implement a speed bump as “attention as a me-

chanic” (Miller et al., 2024, p. 8). (De-)acceleration

through input devices can be a significant mediator

of interaction, such as writing a tweet using an old-

fashioned typewriter (Cremaschi et al., 2024). The

user receives an overview of past statements in order

to leave the chosen cognitive and perceptual load (in-

tended disruption, the ’eudai-bot’ running in an end-

less loop, statements moving up and down) and thus

enter a merely ’calmer’ phase of interaction. An ex-

ample can be seen in Figure 2. Based on the game

Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection Using the Reflective Play Framework

485

Figure 2: The text statements are displayed again with addi-

tional questions to guide the students (phase of slowdown).

principles of slow serious games (Marsh, 2016, p. 50),

this situation aims to open up opportunities for think-

ing and reflection. In addition, according to number

10 of the design guidelines for slow serious games

(Marsh, 2016, p. 50), the user can use a button to call

up random reflection questions to address the con-

cepts. These are displayed via a random generator

in the respective text boxes.

2.3 Questioning

In the sense of “demanding self-explanation”, a

“refection-in-action” is enabled in the questioning

section (Marsh, 2016, p. 10-11), i.e. the student

should translate the confrontation with the perspec-

tives into their own explanations. This process is di-

vided into two parts in the interaction: (1) The stu-

dents formulate their own quotation of the topic so

that their own interpretation and thus a reflection pro-

cess and perspective-taking are initiated. This first

step of questioning can be seen in Figure 3. (2)

Figure 3: The student must become active by providing

their quotation (phase of questioning).

Then, along the design principle of “ambiguous in-

structions” (Miller et al., 2024, p. 11), the students

should express themselves creatively and visually on

a small HTML5 canvas, which they associate with

their interpretation of the topic. This second step can

be seen in Figure 4. We have used a simple edi-

tor (color selection and brush thickness), which, after

saving the artwork, redirects to the page that enables

the revisiting of the experience.

Figure 4: A minimalist painting surface designed to inspire

artistic activities (phase of questioning).

2.4 Revisiting

In the revisting phase, we have chosen a form of re-

flective revisiting, i.e. the user receives a simple vi-

sualization of his or her painting, his or her quote,

and a dwell time within the system. Actively inform-

ing users about their time spent on video platforms

initiates reflection processes (Sathya and Nakagaki,

2024). The times are not stored user-specifically, as

a shift in extrinsic motivation should be prevented

(focus shift to high dwell times in the system, in-

stead of serious engagement with topics). Thus, from

our perspective, there should be no direct reward for

long dwell times in the system. Forms of evaluation

may cause decreases in creativity (Amabile, 1982),

complex problem solving (McGraw and McCullers,

1979), and deep conceptual processing of informa-

tion (Grolnick and Ryan, 1987). However, at the end

of the phase, a small fireworks simulation is played

in the background to acknowledge the time spent in

the system by the student (an example can be seen in

Figure 5). The actual moment of the enhancer takes

place in the last interaction.

Figure 5: The image is displayed with slight transparency in

the background, and the user’s quote definition is displayed

next to the concepts. The user is simply informed positively

about the dwell time in the system (phase of revisiting).

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

486

2.5 Enhancer

A random generator chooses a slogan from a list of

ready-made motivational statements at the top of the

last page. It is intended to motivate reflection prac-

tices outside of this environment and has been pre-

selected by the author. It is a combination of the

design template, explicit encouragement of reflection

and breaking the fourth wall (Miller et al., 2024), as

the student should be motivated to engage in out-of-

system reflection processes. Furthermore, for the ex-

ploration of multiple perspectives of the game experi-

ence, all user artworks are displayed on the last page

of the interaction - no likes, just text, acronym, and

the artwork, arranged from last to newest timestamp.

It can be seen in Figure 6. We want to emphasize

Figure 6: At the end of the interaction, the user sees the

works of the other users in their variety. A random quota is

intended to reinforce the effectiveness of reflective activities

(phase of enhancer).

this feature of the prototype, as social reflection is

mentioned as an important research object in reflec-

tive play: “Lastly, refective revisiting features can be

made into social learning activities. Instead of re-

viewing your own processes and playbacks, review-

ing your friends’ gameplay can provide opportunities

for comparison, mentorship, and other forms of so-

cial learning.” (Miller et al., 2024, p. 16). However, it

is not only friends with whom one interacts but each

student of the platform and their visual and textual

ideas. In the course of the user study, we are par-

ticularly interested in whether this would contribute

to a more collective enjoyment of the interaction or

whether it would lead to an uncomfortable and thus

unwanted sharing of personal artworks. In the fol-

lowing, we want to discuss the initial results of the

experience with ’eudaily’ and highlight both positive

and negative aspects, as well as further ideas, so that

multiple implications for the development of reflec-

tive play emerge.

3 CASE STUDY

We recruited 21 participants on Prolific who explic-

itly indicate a student status in their profiles. They

had to declare an interest in philosophical activities

and provide a 100% acceptance rate on this platform,

i.e. a submission was never rejected due to suspi-

cious participation. This interest in philosophy was

a prerequisite for authentically analyzing the effec-

tiveness of the prototype. The age range was be-

tween 18 and 46. Eleven men (52.38%), nine women

(42.86%), and one trans man (4.76%) took part in

the study. The participants also shared their nation-

ality (anonymized): Eleven European students, seven

African students, and three students from America.

We collected information consent that allowed the

use of their statements for sharing in a research ar-

ticle. Furthermore, we paid £5 for each participation.

On average, the test participants spent 36.03 minutes

on ’eudaily’ and taking part in the subsequent sur-

vey. Participants were required to write a statement

of at least 50 words detailing the negative and positive

points of use. In addition, participants had to answer

all items of the three subscales (reflection, rumination,

and self-focused thinking) of the “Reflection, Rumi-

nation and Thought in Technology (R2T2)” scale (Lo-

erakker et al., 2024). With the items for reflection, the

consciousness of one’s behavior as well as the sup-

port of reflective activities are measured in interaction

with a technology. The items of the rumination sub-

scale are developed for assessing the amount of creat-

ing negative thought cycles and reflecting on past sit-

uations in interaction with technology. The items of

the self-focused thinking scale measure the influence

of technology on the analysis of one’s feelings and

the origin of thoughts. The subscales should be used

to measure the extent of these aspects in interaction

with ’eudaily’ to determine whether all forms of the

scale-related aspects are addressed in the interaction.

We intended to analyze whether all forms of reflec-

tion are addressed in the interaction. The Cronbach’s

alpha of the subscales were at least satisfactorily con-

sistent (Taber, 2018), so that implications could be de-

veloped on this basis (reflection: α=0.81, rumination:

α=0.66, self-focused thinking: α=0.88).

4 FINDINGS & PRACTICAL

IMPLICATIONS

In general, there are five specific practical implica-

tions based on this use case. However, some general

statements can be derived regarding the overall pleas-

antness of ’eudaily’: The most frequently mentioned

Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection Using the Reflective Play Framework

487

was the variety of perspectives to be evaluated in the

disruptive phase together with the ’Eudai-Bot’ (n =

5). Four participants share the positive feedback of

an artistic expression on the canvas (19.05%). One

participant (no. 14) positively emphasizes the lack of

pressure for perfection described in the painting pro-

cess. Another participant (no. 2) highlighted the pos-

sibility of being able to focus on the reading process,

which has been evaluated positively. To summarize

and structure each of the five practical implications of

this use case, we will address them in the respective

subsections.

4.1 Positive Disruption

The use case showed that, as assumed by the authors

of the framework (Miller et al., 2024), alternative

mixed-affect experiences can also serve as a design

template during the disruptive phase. The students’

statements showed that engaging with philosophical

perspectives was sufficient for a positive reflective ex-

perience. This is also shown by the quantitative anal-

ysis of the R2T2 subscales that we could not measure

any negative reflection experiences, but significantly

more self-focused thinking and reflection pointing to

reflection based on positive disruption. Low values

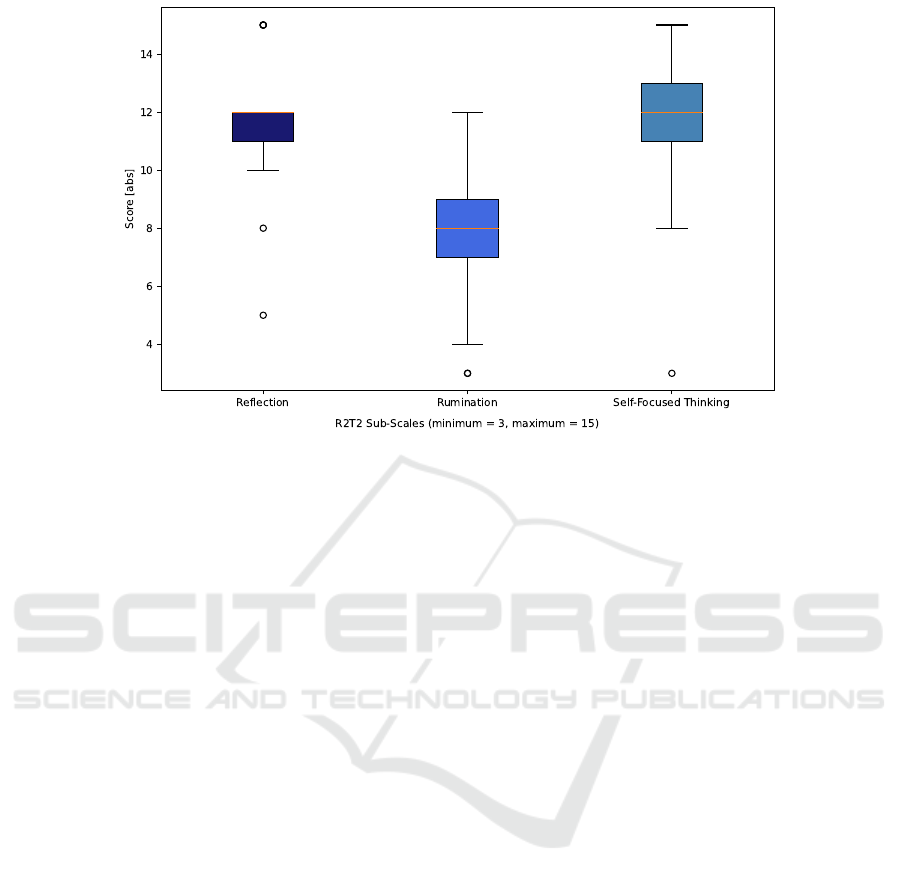

were found for rumination, i.e. a t-test for reflection

and rumination shows a significant difference in the

mean values (t=4.939, p¡.000***). This also applies

to the mean values of the subscales of self-focused

thinking and rumination (t=4.546, p¡.000***). The

items for rumination are scored lower in comparison

to each case (the results are illustrated in Figure 7).

This seems logical, as rumination “is considered to

be a negative cognitive process, as it can involve a

focus on loss and failures” (Loerakker et al., 2024,

p. 2). Thus, the use case discovered an additional

form of disruption as previously stated: positive or

morally-elevated dissonance. According to the quan-

titative analyses, confrontation with new, inspiring

perspectives that challenge one’s patterns of thought

also leads to reflection processes and promotes self-

focused thinking. It may be close to feelings such

as awe and moral elevation, which can be assigned

to the eudaimonic emotional field (Landmann, 2021).

Based on the results, these forms of positive eudai-

monic emotions in connection with reflection pro-

cesses are equally design principles of disruptions. In

other words, it may be sufficient to create spaces of

disruption that are not always negative or concern vi-

olation of user expectations, but also to create disrup-

tions with positive eudaimonic emotions.

4.2 Variety During Disruption

The most frequently mentioned positive aspect among

the participants was the variety of perspectives (n =

5, 23.81%), e.g. participant no. 4 wrote: “I really

appreciated the variety of sentences selected and the

possibility of giving my point of view too. I think it’s

something that makes you think”. An alternative in-

terpretation is given by the 21st participant: “I really

liked that many quotes were presented, so we could

tune in to the topic and learn from those who figured it

out in their way”. Other participants also commented

positively on the variety of perspectives, e.g. Partici-

pant No. 17: “I found it interesting to read all of the

different ideas that where being put forward”. Partic-

ipant no. 6 adds: “I really enjoyed the simplicity of

the visuals and how the screen was organized to pro-

vide all different perspectives while not being visually

overwhelming”. Lastly, Participant No. 3 manifests:

“I really appreciated the variety of sentences selected

and the possibility of giving my point of view too”.

Thus, the second practical implication of this use case

is that a variety of perspectives during the disruptive

phase may enhance the reflection process instead of a

single event such as a narrative twist. From this, we

conclude that confronting a variety of perspectives,

opinions or interpretations can be sufficient as a dis-

ruptive momentum.

4.3 Customizing the Disruption

A fourth practical implication was drawn from the use

case, namely that the customization of the ambience

and interaction spaces was noticeably demanded. For

example, participant no. 18 stated that he or she “felt

that the overall ‘atmosphere’ was a little too unse-

rious and overly ‘spiritualistic’ for my tastes, which

mainly regards the particular way the content was

presented (e.g. floaty animated UI, walking android

in the backdrop), and not the content itself ”. Par-

ticipant no. 13 mentions the customization of the

theme as a specific point for improvement: “I found

the theme (the color mostly) set a particular mood,

about which I wasn’t sure how to feel. It made me

a little pensive, but in a “gloomy” sense (similar to

how rainy weather may trigger a particular kind of

atmosphere). Overall, I found it a bit distracting and

would prefer the option to choose a theme”. In two

cases there was an explicit wish to add ambient music.

Participant no. 12 writes: “ambient music should be

used to enhance the aspect of focus”. Participant no.

15 adds: “For improvements, I think having some fit-

ting ambience music in the background would further

enhance the experience”. Finally, participant no. 13

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

488

Figure 7: The evaluation of the subscales of the R2T2 scale. The Rumination subscale showed significantly lower scores on

average.

mentioned the capacity to choose the topic in the in-

terface instead of using a randomizer: “At the outset, I

would have preferred an option that listed how many

topics there were from which to choose - I did want

to explore others, [...]”. The supposedly subjective

aspects of interaction design have the practical impli-

cation of wide modification of the disruption such as

the ambience or even the topic. It may indicate that an

overly prefabricated reflection procedure does not al-

low for the desired degree of reflection in the system

for each student. For two students, the ’Eudai-Bot’

was irritating or even annoying in the first step. This

results in the potential importance of influencing the

design of disruptive events and following steps of the

reflective play experience.

4.4 Instructive Reflection While

Questioning & Slowdowns

There is another important practical implication for

the subsequent steps of slowdowns and questioning.

The principles of slow serious games explicitly de-

mand the avoidance of instructions in two points

(“7. No commentary/narration used/permitted” and

“8. No extra information or text boxes displayed dur-

ing gameplay” (Marsh, 2016, p. 50)). The participants

were sometimes unable to understand the phases and

the corresponding task. Participant no. 19 writes:

“And as for the project itself in general I would add

a bit of an introduction, a really easy task to get me

comfortable or something like that”. Participant no.

4 mentions the importance of additional questions: “I

think It could be improved by adding questions. What

I mean is, instead of just having the quotes, also hav-

ing questions that make people reflect and think by

themselves about the topic”. Participant no. 1 clearly

demands: “I would probably add further explanation

if I where you”. It seems to be not clear from the expe-

riences of the students what exactly needs to be done,

what the next steps are, and what is aimed for within

the interaction. The participants were informed in ad-

vance in the introduction to the study that they would

encounter such a prototype. However, there is still a

certain need for guidance in the process itself. The use

case has shown that this guidance cannot be always

implicitly derived from the events and that textual in-

formation can be useful. Even though they should be

avoided during phases of questioning and slowdowns,

a minimum introduction and help options are recom-

mended.

4.5 Variety of Self-Expressiveness

In the questioning phase, the need for a variety of per-

sonal expressiveness is particularly evident. Two par-

ticipants stated that the reflection is only expressed

by their quotation and minimal painting should be ex-

panded by including other forms of expression. Par-

ticipant no. 10 mentions writing a description and

documenting expressions of feelings: “maybe you

should find a way for the user to be able to ‘paint’

the concept without actually having to draw,- maybe

write a description? explain their feelings regarding

the concept? [...]”. Participant no. 21 states: “How-

Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection Using the Reflective Play Framework

489

ever, I missed having to write more on the topic in my

own words. Making a quote makes you want to think

philosophically and therefore you miss the important

part of self-reflection. Furthermore the artistic part is

very controversial in my opinion because it’s the kind

of thing that only works for some people”. On the

other hand, participant no. 14 writes: “[...] the art-

work wasn’t perfect but I enjoyed the process”. The

necessity of different forms of expression of reflection

can be derived from these perspectives. In the diver-

sity of statements, some may want to express them-

selves artistically, others may want to avoid it. In the

systems of reflection, a wide range of forms of ex-

pression must be made possible, which also enables

reflection in the final phase of enhancement.

Finally, one statement regarding the presentation of

other artworks and quotes by other students should be

addressed. A participant (no. 20: “It was interest-

ing to see the user(?) generated quotes at the end,

[...]”) briefly commented positively on the viewing

of other participants. However, all other participants

did not mention any concerns or further positive com-

ments. It may therefore not have been perceived as

having any explicit significance in the interaction, but

merely as an ’extra’ to one’s interaction. It may make

sense to anchor these social aspects of reflection in

the interaction at an earlier stage (e.g. questioning).

This research question, which arises from the implicit

derivation of non-mentioning, needs to be analyzed in

an alternative system design.

5 LIMITATIONS

The first limitation of the practical implications is the

reference to only one use case and a limited number

of students participating from three nationalities (Eu-

rope, Africa, and America). In its novelty, however,

it may serve as a useful foundation for future imple-

mentations of the reflective play framework, as it rep-

resents the first application of this framework. The

second limitation is the lack of analysis of the long-

term effect. With the scales, we have only measured

a short-term perception of reflective activities. In the

next step, we aim to analyze the long-term effect by

using well-being metrics, e.g. with the Question-

naire for Eudaimonic Well-Being (QWEB) (Water-

man et al., 2010). The final limitation is the inclusion

of students who are explicitly interested in philoso-

phy (using the profile information on Prolific). For

further research, transfer effects and development of

interest are important for students who are not neces-

sarily enthusiastic about these eudaimonic activities,

but who may be inspired by the interaction. For ex-

ample, one participant (no. 10) comments as follows:

“[...] liked it a lot, and would possibly use it in my

down time, but I must say I have an interest in these

subjects (although not an intense one or anything) so

I don’t know if people that hadn’t taken a class on the

matter would feel the same”. We want to address this

question in further studies.

6 CONCLUSION

To summarize, there are five practical implications for

technologies to enhance reflective practices: (1) Pos-

itive disruption can be a design element, i.e. being

confronted with fragments (even if only textual) can

already generate positive forms of disruption that ini-

tiate reflective processes. (2) Diversity of perspec-

tives can serve as a design concept for positive dis-

ruption. (3) The technology should be customizable

regarding ambience and interaction space for reflec-

tion. (4) Instructions can be helpful during phases of

slowdowns, even if the user’s free exploration has a

higher priority in reflective activities. (5) The user

must be able to develop his or her reflections play-

fully through a variety of self-expressive mechanisms.

To conclude, these five initial implications expand the

development spectrum around the question of eudai-

monic and reflection-enhancing technology and are

more closely analyzed concerning the aforementioned

limitations.

REFERENCES

Altarriba Bertran, F., M

´

arquez Segura, E., and Isbister, K.

(2020). Technology for situated and emergent play:

A bridging concept and design agenda. In Proceed-

ings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, CHI ’20, page 1–14, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A

consensual assessment technique. Journal of Person-

ality and Social Psychology, 43(5):997–1013.

Baumer, E. P. (2015). Reflective informatics: Conceptual

dimensions for designing technologies of reflection.

In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’15,

page 585–594, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Behzad, A. (2023). Co-shaping temporality: Mediating

time through an interactive hourglass. In Compan-

ion Publication of the 2023 ACM Designing Interac-

tive Systems Conference, DIS ’23 Companion, page

241–245, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

490

Cole, T. and Gillies, M. (2022). Emotional exploration and

the eudaimonic gameplay experience: A grounded

theory. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference

on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’22,

New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Ma-

chinery.

Cremaschi, M., Dorfmann, M., and De Angeli, A. (2024).

A steampunk critique of machine learning accelera-

tion. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Designing In-

teractive Systems Conference, DIS ’24, page 246–257,

New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Ma-

chinery.

Grolnick, W. S. and Ryan, R. M. (1987). Autonomy in

children’s learning: An experimental and individual

difference investigation. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 52(5):890–898.

Halln

¨

as, L. and Redstr

¨

om, J. (2001). Slow technology – de-

signing for reflection. Personal Ubiquitous Comput.,

5(3):201–212.

Huta, V. (2016). Eudaimonic and hedonic orienta-

tions: Theoretical considerations and research find-

ings. Handbook of eudaimonic well-being, pages 215–

231.

Joers, J. M. and De Luca, E. W. (2024). Perfect eudai-

monic user experience design that aristotle would have

wanted. In Companion Publication of the 2024 ACM

Designing Interactive Systems Conference, DIS ’24

Companion, page 96–101, New York, NY, USA. As-

sociation for Computing Machinery.

Kwon, S., Yoo, D. W., and Kang, Y. (2024). Spiritual ai:

Exploring the possibilities of a human-ai interaction

beyond productive goals. In Extended Abstracts of the

2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, CHI EA ’24, New York, NY, USA. As-

sociation for Computing Machinery.

Landmann, H. (2021). The bright and dark side of eudai-

monic emotions: A conceptual framework. Media and

Communication, 9(2):191–201.

Li, J., Kwon, N., Pham, H., Shim, R., and Leshed, G.

(2023). Co-designing magic machines for everyday

mindfulness with practitioners. In Proceedings of the

2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference,

DIS ’23, page 1630–1647, New York, NY, USA. As-

sociation for Computing Machinery.

Liedgren, J., Desmet, P. M. A., and Gaggioli, A. (2023).

Liminal design: A conceptual framework and three-

step approach for developing technology that delivers

transcendence and deeper experiences. Frontiers in

Psychology, 14.

Loerakker, M. B., Niess, J., and Wo

´

zniak, P. W. (2024).

Technology which makes you think: The reflection,

rumination and thought in technology scale. Proceed-

ings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and

Ubiquitous Technologies, 8(2).

Marsh, T. (2016). Slow serious games, interactions and

play: Designing for positive and serious experience

and reflection. Entertainment Computing, 14:45–53.

McGraw, K. O. and McCullers, J. C. (1979). Evidence of a

detrimental effect of extrinsic incentives on breaking

a mental set. Journal of Experimental Social Psychol-

ogy, 15(3):285–294.

Mekler, E. D. and Hornbæk, K. (2016). Momentary plea-

sure or lasting meaning? distinguishing eudaimonic

and hedonic user experiences. In Proceedings of the

2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, CHI ’16, page 4509–4520, New York,

NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Miller, J. A., Gandhi, K., Whitby, M. A., Kosa, M., Cooper,

S., Mekler, E. D., and Iacovides, I. (2024). A design

framework for reflective play. In Proceedings of the

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Sys-

tems, CHI ’24, New York, NY, USA. Association for

Computing Machinery.

Pasumarthy, N., Nisal, S., Danaher, J., van den Hoven, E.,

and Khot, R. A. (2024). Go-go biome: Evaluation of a

casual game for gut health engagement and reflection.

In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Fac-

tors in Computing Systems, CHI ’24, New York, NY,

USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Sarkar, A. (2023). Should computers be easy to use? ques-

tioning the doctrine of simplicity in user interface de-

sign. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Confer-

ence on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI

EA ’23, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Sathya, A. and Nakagaki, K. (2024). Attention receipts:

Utilizing the materiality of receipts to improve screen-

time reflection on youtube. In Proceedings of the CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

CHI ’24, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

Schrier, K. K. (2024). How do we teach eudaimonia through

games? In Proceedings of the 19th International Con-

ference on the Foundations of Digital Games, FDG

’24, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing

Machinery.

Soffel, J. (2016). Ten 21st-century skills every student

needs. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/03/

21st-century-skills-future-jobs-students/. Accessed:

2024-09-01.

Stephanidis, C., Salvendy, G., Antona, M., Chen, J. Y. C.,

Dong, J., Duffy, V. G., Fang, X., Fidopiastis, C.,

Fragomeni, G., Fu, L. P., Guo, Y., Harris, D., Ioannou,

A., ah (Kate) Jeong, K., Konomi, S., Kr

¨

omker, H.,

Kurosu, M., Lewis, J. R., Marcus, A., Meiselwitz, G.,

Moallem, A., Mori, H., Nah, F. F.-H., Ntoa, S., Rau,

P.-L. P., Schmorrow, D., Siau, K., Streitz, N., Wang,

W., Yamamoto, S., Zaphiris, P., and Zhou, J. (2019).

Seven hci grand challenges. International Journal of

Human–Computer Interaction, 35(14):1229–1269.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of cronbach’s alpha when de-

veloping and reporting research instruments in science

education. Research in science education, 48:1273–

1296.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert,

R. D., Williams, M. K., Agocha, V. B., Kim, S. Y.,

and Donnellan, M. B. (2010). The questionnaire for

eudaimonic well-being: Psychometric properties, de-

mographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The

journal of positive psychology, 5(1):41–61.

Eudaily: Supporting University Students in Daily Eudaimonic Reflection Using the Reflective Play Framework

491