Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data

Visualization

Alberto Meouchi, Enrique Casillas and Sarah E. Williams

Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, U.S.A.

Keywords: Empathy, Human-Centered Computing, Data Visualization, Visualization Design and Evaluation Methods,

Migration, Interactive Games, Empathy, Knowledge Retention, Venezuelan Diaspora, Policy,

Human-Centered Computing, Interaction Design ~ Empirical Studies in Interaction Design, Applied

Computing, Education, Interactive Learning Environments.

Abstract: One of the biggest challenges in developing data visualizations used for humanitarian advocacy and policy

change, is creating empathy for the experiences of people described in the data. Summarizing their hardship

as numbers and charts does not do justice in describing the often-traumatic experiences they face. In many

cases the results of these data visualizations often further remove the subjects from their story making it more

difficult for viewers of the data visualization to empathize with their cause. Our research sought to change

this dynamic through the creation of Vida Migrante, an online interactive game and data visualization

illustrating the trade-offs migrants make every day. Rather than creating graphs or charts from the survey

data collected by our partners at the World Food Programme, our interactive visualization uses that data to

drive the interactive game experience for our audience to help them learn about the migrant experience. In

this paper we illustrate how this interactive game/visualization helped to create empathy in its viewers.

Drawing from literature on measuring empathic behavior, our research team developed a delivered a user

surveys that allowed us to measure the level of empathy the game created in users. The results showed that

while most users already had some level of empathy towards migrants, all participants of the study increased

their level of empathy as they were able to step into the migrants’ shoes and learn new facts and conditions

of the migrant experience that they were previously unaware.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past decades, the popularity of interactive

online games not only as an entertainment medium

but also as a tool for educating about humanitarian

issues (Berger, 2002). The introduction of online

games into popular culture has sparked a new way of

thinking about entertainment and education as it

provides a completely new medium. Interactive

games and the concept of “gamification” have been

known to be used to teach and increase awareness of

a broad range of topics, including humanitarian issues

(Papoutsi & Drigas, 2016). However, empathy is an

often overlooked focus when using games to retain

knowledge, particularly for humanitarian issues. This

paper seeks to broaden the studied work of interactive

games as a form of sharing knowledge of

humanitarian topics. It primarily focuses on making

the game’s audience more empathetic to the topic it is

exploring. In this paper, we explore the role of games

in creating empathy by analyzing empathy before and

after playing an existing game on migrant integration

and conducting a user study on its effectiveness to

generate empathy. In light of this, there are two

primary questions this study is trying to answer. (1) Is

empathy generated by playing an online interactive

game about humanitarian topics, and how much is

generated? (2) Do people gain more understanding of

migration through playing the game, and how much

more understanding? While this study specifically

focuses on one particular game, we hope its findings

can help guide the creation of other games, ultimately

bringing important humanitarian topics to light.

1.1 Background

The primary focus of this study is an online

simulation game called Vida Migrante, created to

teach people about the experiences of Venezuelan

migrants living in Ecuador and allow them to

Meouchi, A., Casillas, E. and Williams, S. E.

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization.

DOI: 10.5220/0013347500003912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2025) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 653-665

ISBN: 978-989-758-728-3; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

653

empathize with the subject (covered in Section 1.2.1).

Thus, to properly contextualize this work, some

background must be covered, including the

importance of empathy in technology, definitions of

empathy and interactive games, and a description of

the game itself.

1.1.1 The Importance of Empathy in

Technology

Traditionary technology is not often specifically

deployed to encourage empathy, especially in software

products such as games (Anderson et al., 2010;

Nishida, 2013). However, because of the incredible

growth technology and software have experienced in

recent decades, the importance of creating empathic

experiences has more been important to the

development of games and interactive experiences. For

example, “empathy-creating” material is quite

important for successfully teaching computer science

students about accessibility in the software products

they may create (El-Glaly et al., 2020).

Additionally, as games have become popular,

their role as an empathy-creating medium is also

being studied. Games often receive criticism for

being “anti-empathy” mediums—violent games are

often cited—yet now more than ever, games are being

used to shed light on real-world issues, as discussed

in Section 2.1 (Manney, 2008). Therefore, it is

important to look at how games can be used to

develop empathy towards any topic and how effective

they can be in developing that empathy. Another

challenge in empathy generation is that it takes time

and consistent effort to generate, which is orthogonal

to the goal of modern technology of accelerating

information gain. For example, computer scientists

and psychologists have cited decreased human

attention spans and focus over the last few decades

(Mark, 2023). Empathy creation techniques must

evolve to match this rapid evolution in learning about

new things (Subramanian, 2018).

Those not already empathetic towards certain

topics might have difficulty finding a medium that

allows them to empathize in the amount of time and

attention they are ready to give. Fortunately, the space

of games, with their connotation of being “fun,”

“engaging,” and “interactive,” may be an excellent

way to bring empathy creation into a face-paced digital

world. In our discussion in Section 5, we find that,

there are in fact several key features of online games

that can generate empathy extremely effectively.

Arthur Berger, in Video Games: A Popular

Culture Phenomenon, cites several characteristics of

games, such as being entertainment, having rules,

taking place in an environment, whether real or not,

and, most relevant for this study, being perceived as

“artificial” and not real life (Berger, 2002). From

another point of view, James Gee in Are Video Games

Good for Learning? creates a definition by broadly

categorizing them into problem-solving games,

where players need to solve a problem or tackle some

issue, and “world” games, where players interact with

a simulated world (Gee, 2006).

What makes games different from traditional

media is the high amount of player-environment

interaction, which allows players to immerse

themselves in the situations they are put into. Not

only does this quality of immersion make games fun

and engaging, but it can also be used as an empathy

generation tool, as explained in Section 1.2. Given

this class of empathy games, we hope that by

explicitly studying the effectiveness of our own

empathy game Vida Migrante, others may be inspired

to create similar games so that people around the

world can empathize with important issues and

ultimately help provide a means to alleviate such

issues.

1.2 What Is Empathy?

Empathy in the modern world has been studied in

psychology since the mid-20th century. Rosalind

Dymond defined it as the “imaginative transposing of

oneself into the thinking, feeling and acting of

another,” which today has colloquially become

known as “putting oneself in someone else’s shoes”

(Dymond, 1949). Later authors such as Ezra Stotland

critiqued this definition because it focused too much

on how “accurately” the empathetic person could

predict the other person’s thoughts and actions

(Stotland, 1969). Stotland proposed that while

empathy is the ability of a person to place themselves

into the lives of others imaginatively, it can be

defined as the “vicarious” emotional response the

person feels due to the other person’s emotions. This

looser definition allows us to explore how users

reacting to a game might gain empathy. Within our

definition of games in Section 2.1, oftentimes, there

is no “other” person that people can react to since the

players act as that person and are making the

decisions themselves.

We can explore the facets of empathy generation

to deepen the analysis of such from games. Leiberg

and Anders guide the analysis by studying how

empathy is created (Leiberg & Anders, 2006). Their

findings can be grouped into three categories: (1)

Empathy can be created by reproducing others’

mental states, a process often described as Simulation

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

654

Theory [16]. For example, if someone shows signs of

pain, empathy is created by simulating that pain in our

minds. (2) Empathy can be created through prior

representations and familiarity with situations. Using

the same pain example, empathy can be created when

seeing someone in pain by remembering a time when

we were in pain. (3) Empathy can be developed

through perspective-taking, the act of combining

information from several sources to determine

another person’s mental state.

1.2.1 Migrant Integration Background and

Vida Migrante

Over the last three decades, around seven million

Venezuelans have left their home country, with

500,000 immigrating to Ecuador (International

Migrant Stock | Population Division, n.d.). Many

migrants left Venezuela due to the political and

economic unrest, and have come to Ecuador in search

of better job opportunities, food security, and access

to healthcare and education. However, migrants

trying to integrate into Ecuadorian society and

economy often encounter many challenges, which our

partners as the World Food Programme (WFP)

wanted to explore. As such, in 2022, 920 Venezuelan

households in Ecuador were surveyed to gain

information about their current condition and uncover

their specific vulnerabilities (Lab, 2023b).

Findings from a survey showed a disparity between

the vocational skills the Venezuelan migrants already

had and attainable careers in Ecuador and insufficient

resources for migrants to improve their employment

opportunities. These factors have led to high food

insecurity amongst migrants, to the point that migrants

have been reported putting 90% of their income

towards necessities like food, rent, and health,

preventing them from being able to pursue personal

growth opportunities such as training to improve their

economic situation (Lab, 2023a).

As our research team began to develop

visualizations to illustrate these, among other

findings, we quickly realized that it was hard to

convey the numerous trade-off migrants make every

day. Therefore, our team turned to the idea of creating

a simulation game. Our game, Vida Migrante, is at its

core a data visualization project as real data is being

used to drive the outcomes of players of the game. For

example, all decisions and cards are based on real

migrant data; every decision a user makes has an

“implication text” that is driven by real data, giving

context to the player’s decision.

Vida Migrante: Venezuelan Migrants’ Inclusion

in Ecuador

itself is structured as a single-player,

round-based simulation game where users step into

the shoes of a migrant and make decisions for them.

As a brief overview, users first select their migrant

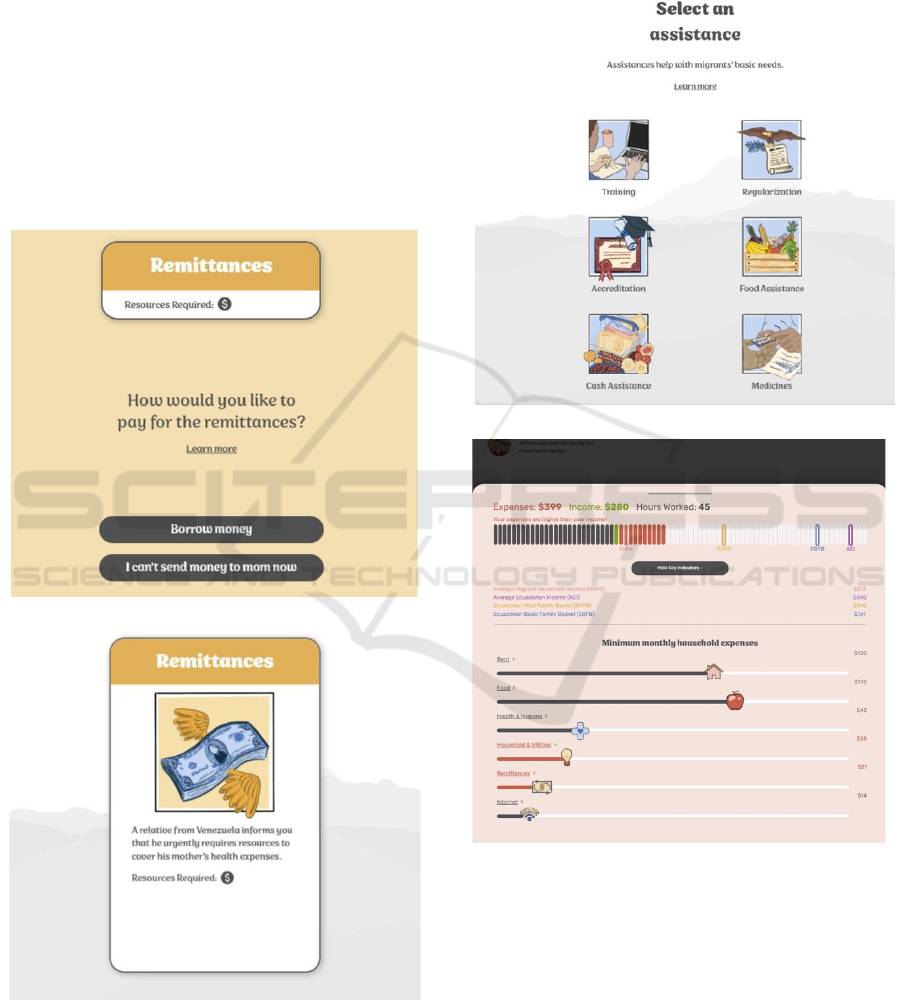

profile and occupation (Figure 1), then proceed

through a series of 4 months (rounds) where each

month they need to decide based on a card they get at

random. For example, users may get the

“Remittances” card, where they need to decide

whether to borrow money to send it back to a relative

in Venezuela or forgo sending money altogether

(Figure 2). Lastly, users can select assistances

provided by nongovernmental organizations which

may help their livelihood, which is meant to emulate

potential policy interventions (Figure 3a).

(a) Migrant Selection

(b) Occupation Selection

Figure 1: Players of Vida Migrante get to choose the

migrant they want to experience the simulation as and their

occupation.

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

655

When borrowing money, for instance, a popup

states that “48% of migrants have to ask for money

from family or friends to meet their basic needs”

(Vida Migrante - Civic Data Design Lab, n.d.).

Similarly, the migrant profiles—Luis, Génesis,

María, and Jose—are not completely imaginary

profiles; instead, they are taken directly from the data.

The profiles were found by running a K-means

clustering algorithm, a form of unsupervised machine

learning, on the migrant biographies sourced from the

WFP survey data, then by taking the average values

of a series of characteristics (such as family size and

immigration status) of four clusters (Lab, 2023b). The

“average” migrant from these four clusters was

transformed into the profiles

(a) Life Event Card

(b) Decision

Figure 2: Players of Vida Migrante receive cards, such as

the “Remittances” card, where they must decide what to do.

we see in the final website so players could empathize

with them. The goal of this game is to be interactive

and engaging yet also strike a balance between its

serious educational aspect and the real issues

migrants in Ecuador are facing today.

(a) Assistances Selection Page

(b) Dashboard

Figure 3: Players can select assistance twice a game which

helps them in their journey to integrate into Ecuador (top).

At most points in the game players can also see their current

resources in a dashboard view, such as their income,

expenses, and hours worked, as well as a breakdown of their

expenses (bottom).

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

656

2 EMPATHY

2.1 Empathy Games

Past works have surveyed the many games made to

educate and bring empathy towards a topic. While

this research does not measure the extent to which

empathy was achieved, a literature review shows how

games designers seek to deploy empathy in their

players. Papoutsi and Drigas survey a variety of

games, citing the importance of simulations in

developing empathy because of their ability to allow

users to see an issue “from the inside”(Papoutsi &

Drigas, 2016). Along those lines, in Migrant Trail,

user simulate the experience of migration. Users can

either play as border patrol agent or as a migrant

themselves, `experiencing what both groups might go

through in real life. In an analysis of Migrant Trail,

Boltz et al. cite the agency given to players as the

main driving factor for generating various feelings,

thus being a good way to create empathy (Council,

2021). This example shows how game designers

recognize the power games hold when it comes to

teaching empathy, particularly in this topic of

migration.

Empathy games are often applied to understand

health conditions. One such example of an empathy

game is That Dragon, Cancer, a game where players

play as a father raising a son with cancer, knowing

that he only has a few more years to live (‘That

Dragon, Cancer,’ n.d.). The interactive game allows

players to make an emotional, empathetic connection

with the father, experiencing the highs and lows of

such a situation. The creator, Ryan Green, even noted

that they chose the video game medium because of its

ability to “[tell] a story the viewer can be present in”

(‘That Dragon, Cancer,’ n.d.). Research on empathy

creation from these games focuses on how it helps

medical students increase their understanding of

patients and their families. For example, Chen et al.

looked at how That Dragon, Cancer can be used to

teach empathy to psychiatry students within a

clerkship curriculum, where they were able to find an

increase in empathy among students (Chen et al.,

2018). Similarly, another study by Ma et al. claims

that the game deployment in a virtual reality format

increased empathy (Ma et al., n.d.). Ma’s study

specifically targeted nursing students as well within

undergraduate nursing programs.

Another notable example of an empathy game

from popular culture is Papers Please by Lucas Pope,

a game in which players play as an immigration

inspector at a fictional border checkpoint, deciding on

who to let through and who to deny by checking the

documentation of immigrants (Papers, Please, n.d.).

The game was well received for immersing players

into this scenario, establishing empathy for the

situations the inspector encounters (Campbell, 2013).

This work demonstrates that an empathy game can be

created for the topic of migration with success, as

shown in the increase of empathy in our study, so the

importance of studying the effectiveness of these

games cannot be overstated.

2.1.1 Testing for and Quantifying Empathy

Creation

How, then, do we test for empathy creation in

interactive games? The first tests for quantifying

empathy in general began by specifically looking at

how well people can share emotions with other

people, as described in Dymond’s work (Dymond,

1949). These tests asked questions about how people

thought other people would rate themselves based on

a set of several personality traits. In these studies,

higher empathy correlated with a more accurate

score, whether or not their predictions matched how

others perceived themselves.

To address this definition of empathy and the

techniques used to quantify empathy were broadened.

Much previous work that inspires this study uses

Likert-scale or Likert-style questions (e.g., “Strongly

disagree” to “Strongly agree”), the most notable

being Mehrabian and Epstein’s Empathy Scale

devised in 1972 (Mehrabian & Epstein, 1972). For

example, Ma et al. describe how they used That

Dragon, Cancer to teach empathy to 69 nursing

students, measuring empathy with a series of Likert

questions (Ma et al., n.d.). Chen’s study on That

Dragon, Cancer explicitly cite using the Jefferson

Scales of Physician Empathy to quantify empathy,

which also uses 7-point Likert-style questions (Hojat

et al., n.d.). This scale, used in health professions

education and patient care, is inaccessible in our

context, so we needed to create our scale for human

migration. Kletenik and Adler describe a game they

used to encourage empathy towards accessibility in

computer technology, specifically colorblindness

(Kletenik & Adler, 2022). This study seeks to

replicate and expand on a similar line of work with

Vida Migrante to see if games can create empathy

toward this topic.

3 METHODOLOGY

Due to empathy's qualitative nature, the research

deployed a methodology drawing on this previous

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

657

research involving a user study that asked several

questions related to empathy before users played the

game and then asked the same questions afterward.

3.1 User Study Design

The user study had four sections. First, subjects

answered demographic questions about their prior

knowledge of the topics (Section 3.1.1). Second, they

answered “Cognition Questions” using Likert-style

scales to assess their initial empathy and

understanding of human migration topics (Section

3.1.2). Third, they played through the game and

vocalized their thoughts and decision-making to the

researcher (Section Section 3.1.2). Lastly, they

answered the exact Cognition Questions, which we

compared to their original responses (Section Section

3.1.2). The last section had questions about the game

and their feelings, allowing them to answer open-

ended questions about their experiences.

3.1.1 Demographic and Prior Knowledge

Questions

The user study first asked demographic and general

prior knowledge questions to get context for each

participant. The demographic questions include race,

gender, ethnicity, and education level. The familiarity

questions asked how familiar participants are with

migration and interactive games, even asking

questions such as if they know a migrant and how

many hours of video games they play a week.

Respondents were allowed not to respond to any of

the questions for privacy and comfort. However, in

the final discussion, these responses affect how users

interact with the game and their empathy towards the

topic.

3.1.2 Game Playthrough and Questions

The survey has eleven qualitative questions that allow

respondents to answer on a 7-point Likert-style scale

from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” for

each question (Cognition Questions in Table 3.1).

Each cognition question aims to answer either the

empathy research question or the understanding of the

issue research question (Section 1), and some

questions try to answer both. Despite the qualitative

nature of the questions, the response is quantitative

because the score is a numeric value from 1 (Strongly

Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). We added up all the

scores for the 11 questions to determine a final

“Empathy Score” (E).

The third section is where participants explored

and played through the online simulation game Vida

Migrante. This section was the focus of the study, as

not only could users learn about and empathize with

human migration, but we could also get a glimpse into

how users approached the material. During this

section, we asked subjects to explain their thought

processes throughout the game. Participants could

comment on the material they were exploring, any

issues they saw with the game, and most importantly,

their thought process as they made decisions that

actual migrants may need to make. As seen in the

discussion section, these comments by participants

reveal particularly insightful findings on how users

gain empathy and understanding as they go through

the game. Because it is important to hear these

participant comments, this study section was

conducted as a one-on-one meeting in an in-person

setting.

The fourth section asked the same cognition

questions to compare participants’ feelings before

and after the playthrough. For instance, once the

empathy score had been calculated before the

playthrough (E

before

) and after the playthrough

(E

after

), we could calculate the change in empathy and

understanding, giving us our final quantitative results.

Note that these values' percent change (∆E/E

before

) is

used in the final results for a more meaningful

measure.

The survey asked additional follow-up questions

on the users’ experience with the game listed (Table

3.2). These questions provided us with rich, open-

ended feedback that we could use to determine how

successful the game was in generating empathy and

understanding toward human migration. As discussed

in the results section, open-ended question 1 was

particularly useful for gauging changes in

understanding (Section 4.2), while question 2 was

crucial to seeing changes in empathy (Section 4.1). A

total of fifty-two respondents were surveyed and

played the online simulation game. At a high level, all

respondents were college-aged students (ages 18-29)

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This

may introduce some biases, but the study results

provide great insights.

4 RESULTS

The data from our survey reveals that our game did

increase empathy in the people we surveyed, and this

chapter discusses several key takeaways and insights

made by respondents, showing how it generates

empathy both quantitatively and qualitatively, with

insights about how empathy and understanding were

generated and the respondent demographics and their

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

658

prior familiarity with the subjects. Quotes were taken

from the respondents live during gameplay, not from

the written survey responses; some may be

paraphrased, but their intention is maintained.

4.1 Changes in Empathy

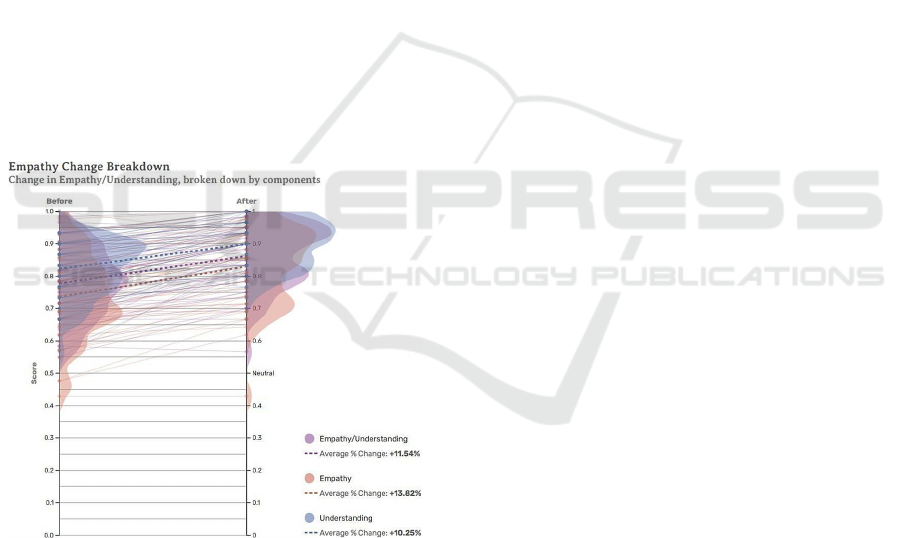

Overall, baseline empathy for the respondents was

already high, with general empathy/understanding of

the issue at 0.78, from of a 0 to 1 scale, before playing

Vida Migrante. (Figure 3)

Breaking this down into the empathy and

knowledge of the issue cognition questions, average

empathy started at 0.74 while average understanding

started at 0.82. Recall from Section 3.1.2 that 1

represents the most empathy, 0.5 represents a neutral

stance, and 0 represents the least empathy. Despite

these already high empathy scores, there were still

increases in empathy and understanding of migration

across the board. More exploration into the

“understanding” results is done in Section 4.2, along

with qualitative evidence showing how knowledge

increased. This section focuses on overall

empathy/understanding of the issue and empathy on

its own, as it is the crux of this research.

Figure 3: Summary of respondents’ empathy scores before

and after playing the online simulation game Vida

Migrante. Scores are broken down into 1) the final

combined scores of empathy and understanding (purple), 2)

the scores given just empathy questions (red), and 3) the

scores given just understanding questions (blue).

On a quantitative level, overall empathy/

understanding saw a significant increase from before

playing Vida Migrante (M = 0.78, SD = 0.11) to after

playing the game (M = 0.86, SD = 0.10), t(51) = 10.5,

p < 0.01.

As referenced throughout the rest of this section,

this corresponds to a 11.54% percent increase. On its

own, empathy increased similarly by 13.82% on

average from M = 0.74, SD = 0.13 to M = 0.83, SD =

0.12 (t(51) = 9.89, p < 0.01). As an important side

note, this distinction between increases in empathy

alone (compared to increases in empathy and

understanding) is calculated by only factoring in

questions specifically targeting empathy. To clarify

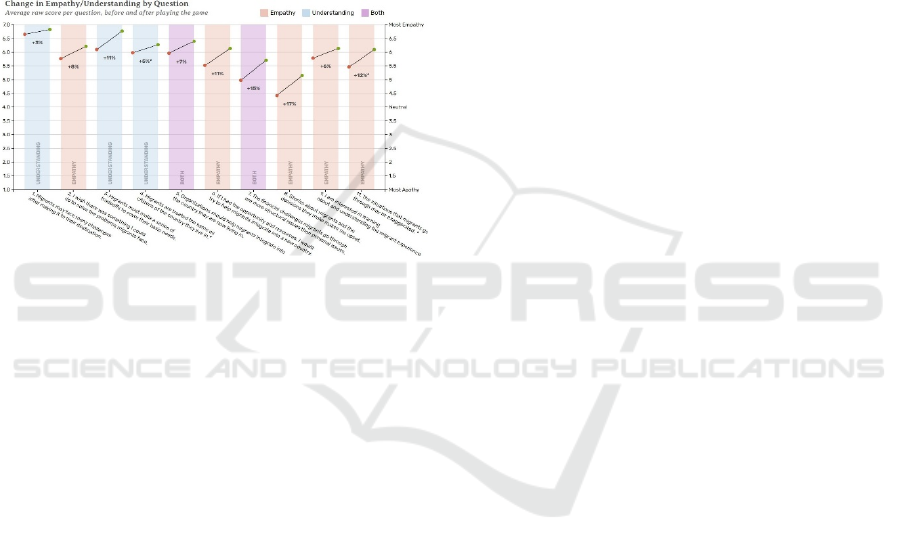

this, we broke down the change in the raw score per

question (Figure 2). Overall, empathy/understanding

factors were found in all 10 questions in the analysis,

while empathy alone factors were found in only the

questions indicated in the red and purple bars. Looking

at the distribution, most respondents showed increased

empathy after playing the game (Figure 3). Some

respondents showed rather stark increases in empathy,

showing that even respondents who previously had

high empathy still gained additional empathy towards

migration.

Additionally, the study shows an interesting trend

that appears to arise, where the lower the starting

empathy score is, the more significant the percent

change in empathy is. However, this may come

naturally partly because high-scoring respondents

probably won’t increase their empathy much because

there is not much more to increase by. Unfortunately,

while we tried to find survey respondents with a

starting empathy score below neutral (0.5) we were

unable to recruit them, so our data has some bias in

that most respondents already have some level of

empathy.

4.1.1 Familiarity with in-Game

“Characters”

The first key insight we found during the study was

that players connect to the migrant profiles in the

game. The primary example of this connection is in

the migrant selection process, where respondents

often chose to play as the character they related the

most to. This connection and relatability support the

“familiarity” facet of empathy generation, where the

more familiar they were with the characters and their

situations the more likely they were to activate certain

parts of memory that established an emotional

connection.

One of the leading examples of this during the

study we found is that many young women chose to

play as Génesis, the only young, single woman out of

the four migrant profiles they could choose from.

Statements like “She aligns more with me,” “I can

make the best decisions for her,” “[She is] more

relatable”, and “[She] feels like the closest one to me”

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

659

show that young women may feel the most

comfortable playing as someone like them, affording

greater relatability and thus creating a stronger

emotional connection to them.

While not everyone picked a migrant, they related

to the most or were familiar with it. Many

respondents simply picked a migrant based on

“vibes” or whoever caught their eye without

explicitly stating why they chose that migrant.

However, we still saw increased empathy among

those respondents after playing. This emphasizes the

relevance of highlighting features of interactive

games to create empathy; one single feature may not

establish that strong emotional connection.

Figure 4: Average raw empathy scores before and after

playing the online simulation game Vida Migrante, broken

down by cognition question. Questions with an asterisk (*)

are negative and have been normalized, as explained in

Section 2.1.2.

4.1.2 Stepping into the Shoes of the

Migrants

Many respondents not only cited a strong connection

with the migrant profiles, but with the migrant

experience itself. This subsection outlines how users

“stepped into the shoes” of the migrants as they made

the decisions presented to them in the game. These

findings demonstrate the “simulation theory” facet of

empathy generation described in Section 1.2, where it

is clear that players were able to reproduce the

thoughts and experiences the migrants would have in

real life. What is fascinating about this finding is that

there is never a time in the game where migrants are

shown making decisions; instead the player makes all

those decisions on their own. Despite this, we were

still able to find empathy generation that reflected this

simulation theory. This may suggest that the

interactivity of games can be a potent tool for

empathy creation and connection with these

experiences, even if they are unfamiliar.

Quantitatively, we look to Cognition Questions 2

and 6 to see how the respondents’ empathy increased

after playing the game due to their emotional

connection with the migrant experience. Question 2

saw an 11% increase in the average raw empathy

score towards “wishing they could help the

migrants.” Question 6 saw a similar 11% increase the

average score where respondents would “try to help

migrants integrate into their new country if they had

the resources.” While not a particularly large change,

these increases show that people may be establishing

emotional connections with the migrants by playing

this game, hoping more and more that they could help

their situation. Note also that these increases occurred

even among respondents who already had relatively

high empathy.

Respondents also provided a lot of qualitative

insights into the empathy generated from stepping

into the shoes of migrants. One of the most revealing

findings was the heavy use of first person pronouns

(I/my/me) when describing their actions. Some

examples from the respondents included statements

like “I have a lung disease”, “I have a partner”, “Let’s

help my friend”, “Cash benefits me now”, and “I need

more money”. The heavy use of these pronouns as

people walked through the game reinforces this idea

that people really feel as if they are the migrant

making these decisions, which is possible precisely

because the game format allows you to do

that.Furthermore, some respondents indicated out

loud that the simulation game made them feel as if

they were experiencing a real situation, or if they

were reliving an experience. The vocabulary and

phrases respondents used hinted at the strong

emotional, empathetic connection with the migrant

situation and the decision making they need to do.

Despite the game being a simulation, many said

phrases indicating that the experiences felt real to

them. Some showed that they shared the risk that

migrants may take in real life, saying things like “I’m

not sure that I can take that risk” and “I’ll risk it and

borrow money, it’ll cost more down the line to treat

it”. Lastly, given this finding of player engagement,

one observation during the study was that many

respondents chose to play again as a different

character to see what their experience would be like.

While unfortunately we were unable to capture a

figure for the exact percentage of respondents that did

this, the observation similarly shows how people

were engaged in the game. Cognition question 9

reinforces this finding, with a 6% increase in

sentiment that people wanted to learn more about the

migrant experience.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

660

4.1.3 Shared Feelings of Distress and

Hopelessness

As we observed during the user study, we indeed

found that many respondents had empathy towards

such struggles. Not only is this shown in the

connection to the migrant profiles and the migrants

experiences, but also, as this section explores, the

recognition that migrants go through a lot of stress.

Given that Vida Migrante provides players with a lot

of context surrounding their situation, these particular

findings support how empathy is generated through

the “Perspective Taking” approach, where players

infer the mental state of the migrants given the

information provided to them, and then imagine how

they would feel in that situation.

Respondents often verbally exclaimed how the

migrant situation and the decisions they had to make

were stressful or upsetting. For example, one

respondent reacted with “It’s kind of sad” when

realizing they could not help a relative with remittances

because they did not have enough money. Similarly,

another noted how “It hurts” when they choose not to

help the community because they have no time. Many

other respondents cited feelings of hopelessness and

being in dire situations, saying things like “There’s no

way to survive”, “Life is so hard”, “Either I borrow

[money] or I die”, and “This is horrible”. Most notably,

some respondents indicated in the open-ended follow-

up questions that they themselves started to feel

stressed or hopeless, or at least acknowledged how it

might be easy for a migrant to feel that way, showing

large amounts of empathy.

We also asked respondents in a follow-up question

how difficult it was to make the decisions presented to

them as migrants. Some respondents mentioned this

difficulty in their open-ended responses, saying, "the

choices involved are a lot more difficult than I

expected” and “migrants have a lot of difficult and

unfair decisions.” This also contributes to the

understanding people gained after playing the game,

realizing the decisions migrants have to make when

facing tough choices. Six respondents found the

decisions not as difficult as expected. However, we

believe this may be because some of the scenarios in

Vida Migrante only allowed users to select a single

option, a limitation in the game.

4.1.4 Specific Mentions of Empathy

Generation

As final evidence that Vida Migrante successfully

created empathy, many respondents cited their own

increases in empathy and emotional connection to the

migrant experience directly from playing the game.

On the emotional aspect, many people mentioned

how the situations were sad or upsetting. Sympathy

can be considered a result of empathy when someone

is going through difficult or stressful situations, as is

often the case for migrants. Many respondents wrote

in the open-ended questions about how the game

made them “feel sympathetic to the migrant

experience.”

There were also mentions of empathy generation,

not only because of the content presented but also due

to how it was presented in the form of a game. For

example, Respondent 4 wrote, “The game made me

experience and empathize with the difficulties that

migrants face more tangibly,” citing specific reasons,

such as how the game put them through “emergency

situations” that prevented them from making personal

progress.

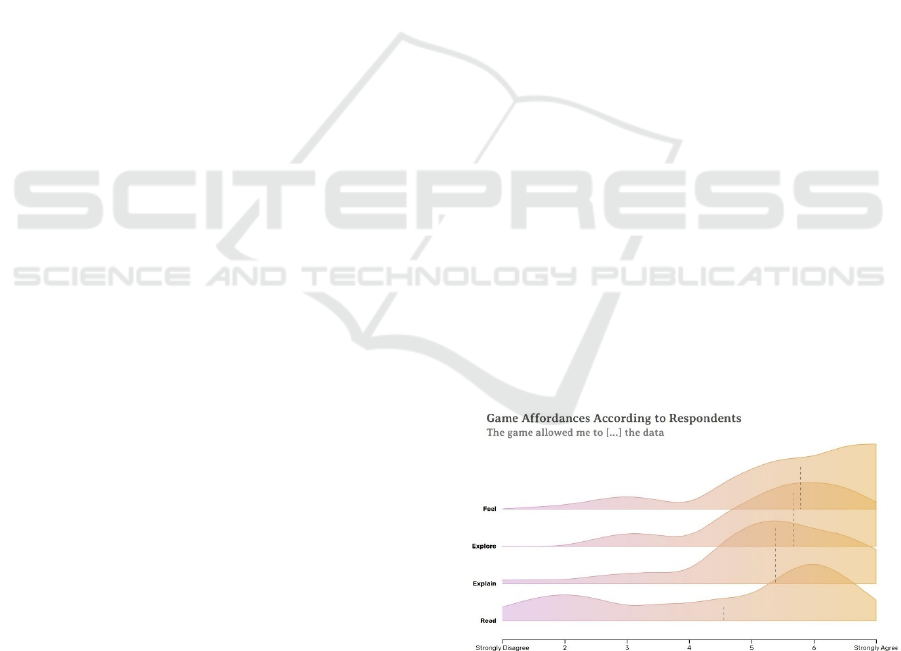

To specifically assess empathy generation, we

wanted to see how users would perceive the migrant

data, given that Vida Migrante visualizes real data

from real migrants in a game format. Inspired by

William Allen’s adaptation of Andy Kirk’s typology

of data visualization, we asked four questions in a

Likert-style format to gauge how much the game

helped players 1) feel the data, 2) explore the data, 3)

read the data, and 4) explain the data(Allen, 2021;

Kirk, 2016). While not entirely clear, results indicated

that players were more likely to explore and feel the

data than read or explain it (Figure 5). We hope future

work can expand on this type of analysis when

examining how games can be used to communicate

data. Regardless, this notion of “feeling” or emotional

connection, which inspired the game’s development

in the first place, supports the conclusion that the

game was successful in creating empathy.

Figure 5: Distribution of responses towards how the

affordances the game provided towards interacting with the

data, inspired by William Allen’s data visualization

typology. The mean response for each of the four categories

is shown as a gray dashed line.

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

661

4.2 Changes in Understanding of

Migrant Issues

Similar to the previous section, this section covers

quantitative and qualitative evidence on the game's

impact, this time diving into the increases in

understanding the respondents' issues after playing

the game.

Overall, we saw an increase in understanding

from before playing the game (M = 0.82, SD = 0.09)

to after playing the game (M = 0.90, SD = 0.07), t(51)

= 6.9, p <0.01. This corresponds with a percent

increase of 10.25%. This increase was smaller than

the increase in average empathy alone, possibly due

to the factors we noted in the respondent

demographics (Section 3.2) and the caveats (Section

3.1). As previously mentioned, initial understanding

score was already extremely high at 0.82. This may

explain the smaller increase, as there was little room

to grow in knowledge of the issue. Nevertheless, we

still found a plethora of qualitative evidence from the

respondents supporting the conclusion that

knowledge of the topic increased, with reactions from

respondents such as “migrants have no control over

their situation” and the fact that there was still a non-

trivial increase in the normalized score is notable.

Additionally, one of the questions we asked as a

follow-up after playing the game was whether or not

respondents felt like they learned something new.

Forty-eight respondents (

≈

92%) said they learned

something new. Although learning something new

does not necessarily equate to understanding, it does

Figure 6: Distribution of how difficult making decisions

was within the game.

give a glimpse into how respondents were able to

make some meaningful takeaways from playing the

game. We also asked an open-ended follow-up

question on what respondents learned (Question 1 in

Table 2), which is the source of much of our analysis

into the generated understanding. The following

subsections dive into four overarching categories in

how understanding was achieved, which we derive

from responses to this question and the overall

sentiment observed from respondents. Note that this

section is less substantive than the empathy results

because our primary focus was on empathy.

4.2.1 Difficulty of the Migrant Experience

The primary area where respondents showed

increased understanding was in seeing how difficult

the migrant experience is. Most respondents found

the decisions they had to make as migrants rather

difficult. However, this section explores the overall

difficulty and struggles in the situations conveyed to

respondents; respondents began to show signs of

understanding that being a migrant trying to integrate

into a new country is extraordinarily difficult, not

only because of the decisions you must make.

The study drew insights into how respondents

gained understanding from one of the open-ended

questions we asked, “If you felt like you learned

something new, what was it?” Note that the responses

we discuss here are related to the difficulty of the

migrant experience, though there are many other

responses related to themes described in the following

subsections. One of the ways respondents recognized

the difficulty of migrant experiences came in the form

of seeing the large families that migrants had to take

care of. One migrant profile in Vida Migrante, in

particular, Luis, was the head of a family of 6,

eliciting shock at how he could care for his family

given the conditions they lived.

4.2.2 Illusion of Choice

Another facet of the migrant experience that players

gained an understanding of was the illusion of choice.

Because of limited resources, they often can only

make one possible decision. Most notably,

respondents noticed that the challenges migrants face

are often not their fault but a structural failure of the

environment in which they live. This was

quantitatively captured by cognition question 7,

where there was a 15% increase in understanding that

challenges are due to structural issues rather than

personal issues, the second highest increase out of all

cognition questions. As always, this numeric

evidence is supported with quotes and open-ended

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

662

responses. For example, respondents noted

realizations of how “some of these choices aren’t

even an option in real life”, or “just how many things

are out of a migrant’s control”/“migrants have no

control over their situation” or “much of the time

[migrants] don’t even have a real decision.” There is

arguably no better way to understand what migrants

go through than to experience it yourself, an

experience this game hopes to provide.

4.2.3 Trade-Offs in Decision-Making

The third major insight respondents gained was an

understanding of the tradeoffs migrants must make

during decision-making. One of the game's goals was

to communicate the sacrifices migrants make to

survive in Ecuador, and the study found it was

successful in doing so. Looking at the quantitative

data, cognition question 3 asked whether respondents

believed that migrants must make tradeoffs to cover

their basic needs, and there was an 11% increase in

this sentiment. Although the raw empathy score was

already high at 6.09, this question significantly

jumped to 6.76.

The study identified three subcategories of

tradeoffs that players noticed and understood. First,

many noted tradeoffs between long and short-term

decisions, which aligned with our goal of depicting

the "assistance" from governments and NGOs.

Respondents described these choices as “Immediate

versus Long-term” or “Short-term needs versus long-

term needs.” Some, especially those with larger

families and high expenses, discussed prioritizing

short-term needs. One respondent, frustrated by

delaying long-term growth, exclaimed, “Ugh, I keep

putting this off,” referring to forgoing the training

assistance. Second, some respondents recognized the

difficult tradeoff between helping others and helping

their own families. A common scenario involved

community support cards, where players had to

choose between helping the community and taking

time off work. One respondent initially focused on

family, saying they “want the family to be healthy,”

but later acknowledged that “community is

important” when faced with the decision. Another

respondent firmly prioritized their family, stating, “I

would not” help someone “to the detriment of my

own family.” Finally, when asked what they learned

by playing the game, many respondents explicitly

mentioned tradeoffs in decision-making. One

respondent mentioned, “Going through the

simulation, my involvement in many of the difficult

financial decisions taught me more about the trade-

offs migrants have to make to put themselves in a

better situation.” Others mentioned how they learned

about “the need to balance between different options”

and “the types of tradeoffs migrants have to make

daily.”

5 CONCLUSION

5.1 Conclusion

This study shows that the empathy game Vida

Migrante effectively generates empathy and

understanding towards human migration in Ecuador.

On a quantitative and qualitative level, respondents

indicated that they were able to better empathize with

the migrant experience and understand the decisions

migrants have to go through daily to survive in their

new home. Furthermore, this research contributes

evidence to the existing literature that games can be

an extremely effective tool for empathy generation,

even for communicating real data in a highly

engaging manner. We also outline a unique method

for measuring empathy in data visualization and

games, which we hope others can build upon.

Interactive games are indispensable for putting

players into another’s shoes and simulation the

experiences that create empathy. Through the

process, users learn about other’s experiences

firsthand and have a greater connection to

information. This research helps establish how data

visualizations can create empathy, helping to develop

a critical literature framing for future developments in

the field, especially for how data visualizations can be

deployed in the humanitarian sector.

REFERENCES

Allen, W. (2021). The practice and politics of migration

data visualization. Research Handbook on

International Migration and Digital Technology, 58–

69. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839100611.00013

Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L.,

Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., Rothstein, H. R., &

Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on

aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in

eastern and western countries: A meta-analytic

review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018251

Berger, A. A. (2002). Video Games: A Popular Culture

Phenomenon. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/978

1351299961

Campbell, C. (2013, May 9). Gaming’s new frontier:

Cancer, depression, suicide. Polygon.

https://www.polygon.com/2013/5/9/4313246/gaming

s-new-frontier-cancer-depres sion-suicide

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

663

Chen, A., Hanna, J. J., Manohar, A., & Tobia, A. (2018).

Teaching Empathy: The Implementation of a Video

Game into a Psychiatry Clerkship Curriculum.

Academic Psychiatry, 42(3), 362–365.

https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40596-017-0862-6

Council, A. I. (2021). Immigrants in the United States.

American Immigration Council.

Dymond, R. F. (1949). A scale for the measurement of

empathic ability. Journal of Consulting Psychology.,

13(2), 127–133.

El-Glaly, Y., Shi, W., Malachowsky, S., Yu, Q., & Krutz,

D. E. (2020). Presenting and Evaluating the Impact of

Experiential Learning in Computing Accessibility

Education. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd

International Conference on Software Engineering:

Software Engineering Education and Training, 49–

60. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377814.3381710

Gee, J. P. (2006). Are Video Games Good for Learning?

Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 1(3), 172–183.

https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2006-03-

02

Hojat, M., DeSantis, J., Shannon, S. C., Mortensen, L. H.,

Speicher, M. R., Bragan, L., LaNoue, M., &

Calabrese, L. H. (n.d.). The Jefferson Scale of

Empathy: A nationwide study of measurement

properties, underlying components, latent variable

structure, and national norms in medical students.

Advances in Health Sciences Education., 23(5), 899–

920.

International Migrant Stock | Population Division. (n.d.).

Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.un.org/

development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-

stock

Kirk, A. (2016). Data visualisation: A handbook for data

driven design. In Data visualisation: A handbook for

data driven design. Sage Publications.

Kletenik, D., & Adler, R. F. (2022). Let’s Play: Increasing

Accessibility Awareness and Empathy Through

Games. Proceedings of the 53rd ACM Technical

Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1,

182–188.

Lab, C. D. D. (2023a). Vida Migrante Project Overview.

Lab, C. D. D. (2023b). Vida Migrante: Venezuelan

Migrants’ Inclusion in Ecuador.

Leiberg, S., & Anders, S. (2006). The multiple facets of

empathy: A survey of theory and evidence. Progress

in Brain Research, 156, 419–440.

Ma, Z., Huang, K.-T., & Yao, L. (n.d.). Feasibility of a

Computer Role-Playing Game to Promote Empathy in

Nursing Students: The Role of Immersiveness and

Perspective. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social

Networking, 24(11), 750–755.

Manney, P. (2008). Empathy in the Time of Technology:

How Storytelling is the Key to Empathy. 19.

https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:7978881

Mark, G., Ph. D. (2023). Attention Span: A

groundbreaking way to restore balance, happiness

and productivity (Unabridged.). Harlequin Audio.

Mehrabian, A., & Epstein, N. (1972). A measure of

emotional empathy.

Journal of Personality, 40(4),

525–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1972.

tb00078.x

Nishida, T. (2013). Toward mutual dependency between

empathy and technology. AI & SOCIETY, 28(3), 277–

287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-012-0403-5

Papers, Please. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2024, from

https://papersplea.se/

Papoutsi, C., & Drigas, A. (2016). Games for Empathy for

Social Impact. International Journal of Engineering

Pedagogy (iJEP), 6(4), 36–40. https://doi.org/

10.3991/ ijep.v6i4.6064

Stotland, E. (1969). Exploratory Investigations of

Empathy11The preparation of this article and all of

the initially reported studies were supported by a

grant from the National Science Foundation. (L.

Berkowitz, Ed.; Vol. 4, pp. 271–314). Academic

Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60080-

5

Subramanian, D. K. R. (2018). Myth and Mystery of

Shrinking Attention Span. 5.

‘That Dragon, Cancer’: Q&A With Developer Ryan

Green « Techtonics. (n.d.). Retrieved October 1, 2024,

from https://blogs.voanews.com/techtonics/2016/01/

22/that-dragon-cancer-qa-with-developer-ryan-green/

Vida Migrante—Civic Data Design Lab. (n.d.). Retrieved

April 11, 2024, from https://civicdatadesignlab.mit.

edu/Vida-Migrante.

APPENDIX

Table 1: Cognition Questions (Empathy and

Understanding). Questions are answered on a 7-point scale

from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (7). If the

question is “Positive,” the higher the agreement level the

more empathy the user has.

Question Details

If you felt like you learned

something new, what was

it?

Respondents first answer a

yes or no question on

whether or not they

learned something new,

then answer this optional

question.

How did this game make

you feel about the migrant

experience?

Aimed to get a qualitative

measure on whether or not

empathy and

understanding was

generated.

Feel free to include any

additional notes/follow up

questions here

Respondents could leave

any comments about the

game here, particularly on

game quality and

suggestions for

improvement.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

664

Table 2: Open-Ended Questions.

Question Posit

ive

Migrants may face many challenges after

making it to their destination.

Yes

I wish there was something I could do to solve

the problems migrants face.

Yes

Migrants must make a series of tradeoffs to

cover their basic needs.

Yes

Migrants are treated the same as citizens of the

country they live in.

No

Organizations should help migrants integrate

into the country they are now living in.

Yes

If I had the opportunity and resources, I would

try to help migrants integrate into a new

country.

Yes

The financial challenges migrants go through

are more structural issues than personal issues.

Yes

Stories about migrants and the decisions they

make makes me upset.

Yes

I am interested in learning about and

understanding the migrant experience.

Yes

It is hard to see how migrants could face

difficult experiences.

No

The situations that migrants go through may be

exaggerated.

No

Vida Migrante: Empathy and the Migrant Experiences Through Data Visualization

665