Diagnosing BPM Governance: A Case Study of Facilitators, Barriers,

and Governance Elements in a Hierarchical Public Instituition

Giovanni Correa

1 a

, J

´

essyka Vilela

1 b

and Mariana Peixoto

2 c

1

Centro de Inform

´

atica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE), Brazil

2

Universidade de Pernambuco (UPE), Garanhuns, Brazil

{gecj, jffv}@cin.ufpe.br, mariana.peixoto@upe.br

Keywords:

BPM Governance, Public Institution, Case Study, Governance Elements, Facilitators, Barriers.

Abstract:

Context: BPM initiatives improve processes and adaptability, with governance as a key factor. Problem: BPM

governance in hierarchical public organizations faces structural challenges. Objective: This study examines

BPM governance in a Brazilian public institution. Method: A case study evaluated objectives, roles, decision-

making, facilitators, and barriers. Results: We identified 8 facilitators and 8 barriers. Core areas showed

more process maturity, while key challenges included lacking prioritization methodology and inconsistent

performance indicators. Conclusions: This research expands BPM knowledge by analyzing governance in

hierarchical institutions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business Process Management (BPM) initiatives aim

to identify and improve organizational work proce-

dures (Beerepoot et al., 2023). These interventions

vary in complexity, sometimes requiring significant

procedural changes that reshape an organization’s op-

erations and value chain (Harmon and Trends, 2010).

However, BPM implementation in public organi-

zations presents challenges, with many projects fail-

ing or remaining incomplete (Syed et al., 2018).

These institutions often exhibit hierarchical structures

(Santos et al., 2024), rigid processes (Syed et al.,

2018), and low BPM maturity (Dutra et al., 2022).

Additional obstacles include cultural rigidity, bureau-

cratic resistance (Santos et al., 2024), and misalign-

ment between strategic goals and BPM initiatives

(Santana et al., 2011)(Valenca et al., 2013). Limited

resources and skills further hinder the advancement of

BPM efforts (Jurczuk, 2021).

Effective BPM governance is crucial for success

(Hernaus et al., 2016)(Jurczuk, 2021), ensuring align-

ment between organizational objectives, roles, and re-

sponsibilities while fostering accountability and con-

tinuous improvement (Santana et al., 2011). Public

organizations, in particular, require robust governance

mechanisms to navigate hierarchical barriers and pro-

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6206-2740

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5541-5188

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5399-4155

mote collaboration (Jurczuk, 2021). Governance also

aids in managing cross-functional activities, enhanc-

ing process integration, and transitioning from un-

structured to structured BPM (Hernaus et al., 2016).

This article argues that before initiating a BPM in-

tervention, it is essential to assess the specific organi-

zational context, especially in terms of governance.

We present a case study investigating BPM gover-

nance competencies in key sectors of a hierarchical

Brazilian public institution. Conducted by a Busi-

ness Process Management Office (BPMO) within a

research and development project, the study examines

governance elements proposed by Valenc¸a et al. (Va-

lenca et al., 2013), including objectives, roles, respon-

sibilities, methodological standards, decision-making

processes, and evaluation mechanisms.

By linking these governance elements to facilita-

tors and barriers, this study contributes to the under-

standing of BPM governance in hierarchical public

institutions. The findings offer practical insights for

implementing structured and effective BPM practices.

In addition to this introductory section, this pa-

per is divided into the following sections: Section

2 presents the theoretical background and related

works; Section 3 presents the research method; Sec-

tion 4 highlights the general results; Sections 5 and 6

present the details of the results according to the Re-

search Questions based on the BPM governance el-

ements; Section 7 discusses the main findings; and,

finally, Section 8 concludes the paper.

Correa, G., Vilela, J. and Peixoto, M.

Diagnosing BPM Governance: A Case Study of Facilitators, Barriers, and Governance Elements in a Hierarchical Public Instituition.

DOI: 10.5220/0013347900003929

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 851-858

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

851

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

2.1 BPM Governance

BPM governance establishes frameworks to ensure

effective BPM implementation aligned with organi-

zational objectives (Jurczuk, 2021). It defines guide-

lines, structures, and resources to facilitate collabo-

ration in BPM initiatives (Kirchmer, 2009). Gover-

nance also involves setting metrics, roles, and respon-

sibilities for managing business processes (Jurczuk,

2021).

Since BPM governance lacks a universal approach

(Jurczuk, 2021), we adopt the elements proposed

by Valenc¸a et al. (Valenca et al., 2013): objec-

tives, organizational structure, roles and responsibil-

ities, activities, infrastructure, methodological stan-

dards, decision-making, and control and evaluation

mechanisms.

2.2 Related Work

Several studies explore BPM governance challenges

and elements. (Jurczuk, 2021) and (Mbengo and

Lumka, 2024) highlight barriers in state-owned en-

terprises, such as cultural rigidity and governance de-

ficiencies. (Doebeli et al., 2011) and (Doyle and

Seymour, 2020) examine governance integration in

corporations, focusing on roles and decision-making.

(Hernaus et al., 2016) and (de Boer et al., 2015) em-

phasize structured governance as key to BPM matu-

rity.

In Brazil, (Santana et al., 2011) and (Valenca

et al., 2013) analyze BPM governance in public insti-

tutions, identifying cultural and organizational chal-

lenges. Our study builds on these findings by apply-

ing governance frameworks to hierarchical public or-

ganizations, offering insights into overcoming BPM

barriers in this context.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

Research Design and Case Selection. This qualita-

tive research uses a case study to examine BPM gov-

ernance elements, facilitators, and barriers in a Brazil-

ian hierarchical public institution.

At the time of the study, the institution had low

BPM maturity and was beginning BPMO activities.

It operates in human resources and processes within

a Brazilian federative state, serving the general pop-

ulation. The workforce exceeded 8,000 employees,

with over 6,000 in core areas (direct public service)

and around 2,000 in administrative roles (supporting

internal sectors).

This study is guided by the following Research

Questions (RQs): RQ1: What elements of BPM gov-

ernance are implemented within the public organiza-

tion? RQ2: What are the key facilitators and barri-

ers to BPM governance in the institution, and what

actions can be suggested to ensure successful imple-

mentation

Research Steps. The BPM governance diagnosis fol-

lowed eight stages: Literature review, Organizational

analysis, Data collection planning, Sample selection,

Questionnaire development, Data collection, Analy-

sis, and Results dissemination.

Managers and technical teams were selected based

on organizational charts and consultations, identify-

ing 24 potential managers. The BPMO manager in-

vited them to a one-hour workshop on Process Man-

agement, with 13 attending. The workshop was cho-

sen due to institutional constraints and BPMO discus-

sions.

The study focused on a public institution with

unique BPM challenges. Given the BPMO’s early-

stage development, quick data collection was crucial.

A questionnaire, detailed in our supplementary mate-

rial

1

, was completed during the workshop. It covered

BPM Governance elements (e.g., roles, responsibili-

ties, control, evaluation) (Rosemann and vom Brocke,

2014) (Jurczuk, 2021), along with inputs on the de-

partment’s value chain, training needs, BPMO scope,

and participant feedback.

The Organizational Structure element was not as-

sessed since the institution already had a process of-

fice.

Before the research, two pilot workshops were

conducted to test question clarity and timing. Partici-

pants were selected based on availability, tenure, and

commitment to BPM. Their responses were excluded

from the final analysis, and they did not join the offi-

cial workshop.

To accommodate availability, the workshop was

held on two dates, following this structure: 1. Open-

ing by the BPMO manager. 2. Presentation of ob-

jectives and agenda. 3. Questionnaire completion by

participants. 4. Final discussion on BPM. 5. Conclu-

sion and acknowledgments.

The analysis of the closed-ended questions was

conducted using statistical methods to provide a

descriptive analysis of frequencies and percentages

based on the total number of respondents.

For the open-ended questions, a qualitative anal-

ysis was conducted following the principles of the-

1

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14858817

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

852

matic analysis. To this end, a separate file was created

for each of the seven open-ended questions, where all

responses were listed and the coding process was ap-

plied. After the coding phase, a table was created in

each file to associate the identified codes with the cor-

responding themes. The results are presented in Sec-

tion 4.

Threats to Validity. We identified potential threats to

validity and implemented strategies to mitigate them.

Internal Validity: To minimize response bias, we en-

sured anonymity and confidentiality, emphasizing the

importance of honest answers. External Validity: As

the study focused on a single institution, we avoided

broad generalizations and suggested future research

with multiple case studies. Construct Validity: We

based our instruments on established literature and

conducted a pilot test to ensure clarity. Reliability: A

strict data collection protocol and double coding im-

proved consistency. Ethical Considerations: We ad-

hered to ethical principles, ensuring informed consent

and data privacy.

These measures collectively strengthened the va-

lidity and reliability of our research outcomes.

4 OVERVIEW OF WORKSHOP

RESULTS

This section presents the results of each of the 19

questions from the questionnaire applied to thirteen

workshop participants.

Participants’ Work Areas (Question 1). Seven par-

ticipants (53.8%) reported belonging to the adminis-

trative area, while six (46.2%) were part of the core

area.

Generation of Sector Demands. Participants were

asked who generates the service demands delivered

by their sector (Question 2). The highest number of

responses indicated that internal sectors of the insti-

tution generate demands (11 responses), followed by

society (9 responses), regulatory bodies (8 responses),

and other entities (6 responses).

Relationship Between Sector Objectives and the

Strategic Plan. Another aspect analyzed was how

the results delivered align with the objectives of the

institution’s Strategic Plan (Question 3). Eight par-

ticipants (61.5%) stated that the results directly con-

tribute to achieving the goals outlined in the strategic

plan, followed by four (30.8%) who responded that

they contribute indirectly but do not feed the indica-

tors for the established goals, and one (7.7%) who re-

sponded that the results contribute both directly and

indirectly.

Management Activities Performed. The assignment

of individuals responsible for managing the services

provided by the respondents’ sectors was also inves-

tigated (Question 4). If affirmative, participants were

asked to provide examples of the main management

activities performed by these managers.

Decision-Making for Service Prioritization. Partic-

ipants were questioned about methods of prioritizing

the services provided by their unit (Question 5). If

affirmative, they were asked to indicate which orga-

nizational needs are considered for decision-making.

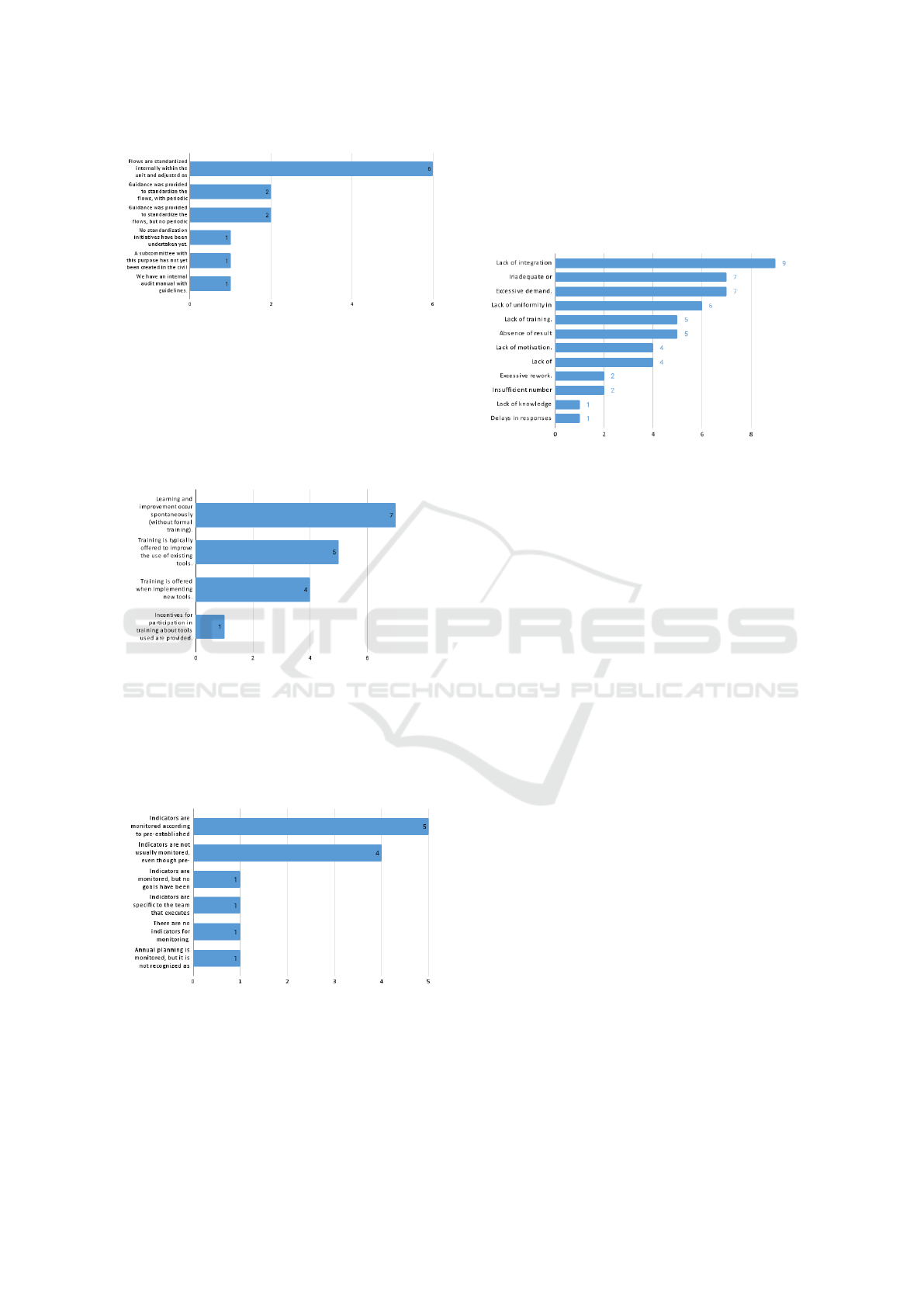

Figure 1 presents the main organizational needs for

decision-making, with the highest number of re-

sponses pointing to the urgency of the demand, cited

by 12 participants.

Figure 1: Decision-making for service prioritization.

Sequence of Activity Execution. The most selected

response to Question 6 was ”There are defined and

documented sequences (in physical or digital for-

mat),” as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Sequence of Activity Execution.

Initiative for Process Flow Standardization. The

most selected response to Question 7 was ”The flows

are standardized internally within the unit and ad-

justed as needed,” as shown in Figure 3.

Main Tools and Systems Used. The tools and sys-

tems were classified into four themes identified during

the coding process: - Internal Tool: Tools developed,

acquired for corporate use, or customized by the in-

stitution. - External Tool: Free tools available to the

general public. - Document: Artifacts generated by

the institution’s work processes. - Not Specified: In-

ternal or external tools.

Diagnosing BPM Governance: A Case Study of Facilitators, Barriers, and Governance Elements in a Hierarchical Public Instituition

853

Figure 3: Initiatives for Flow Standardization.

As a result, 55.0% reported using internal tools,

25.0% external tools, 15.0% documents, and 5.0% of

respondents did not specify.

Training in Tool Usage. Most participants (7) in-

dicated that learning and improvement occur sponta-

neously, while 5 reported that training is usually pro-

vided to enhance tool usage, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Training in Tool Usage.

Indicators for Monitoring Results. Most partici-

pants (38.5%) indicated that indicators are monitored

based on pre-established goals, while 30.8% noted

that indicators are not usually monitored despite the

existence of goals, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Indicators for Monitoring Results.

Measurement of Unit Results in the Institution.

Participants reported varying frequencies for measur-

ing unit results, with the most common being monthly

(5 participants), followed by annually (4 participants),

as shown in Question 11.

Main Challenges in Service Delivery. The primary

challenge identified in Question 12 was the ”Lack

of integration with other areas involved in the ser-

vices provided,” reported by 69.2% of participants, as

shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Main Challenges in Service Delivery.

Improvements to Be Introduced in the Institu-

tion’s Units. The most suggested improvements in

Question 13 were Standardization (9 participants)

and Training (6 participants), followed by recom-

mendations for New tools, Recognition, and Redis-

tribution, among others.

Understanding of the Term ”Business Process

Management.” Most participants (11) defined BPM

as Definitions of flows and standards, while oth-

ers highlighted Improvement in outcomes, Bottleneck

identification, and Sector efficiency.

Means of Acquiring BPM Knowledge. The primary

sources of BPM knowledge reported in Question 15

were Practical experience (9 participants) and Digi-

tal media content (7 participants), followed by Pro-

fessional training and other less frequent methods.

The level of experience and details of practical knowl-

edge were not assessed.

Business Process Management Initiatives in the In-

stitution. In response to Question 16, most partici-

pants reported being Unaware or having Defined an

internal tool (4 each), while fewer cited First con-

tact through BPMO or Having knowledge (2 each).

Dissemination of the Business Process Manage-

ment Culture in the Institution. The main strate-

gies suggested in Question 17 were Training and

events, Communication, Sponsorship and partner-

ships, Awareness, New tools, and Practical demon-

strations in departments.

Benefits of Business Process Management. The

key benefits highlighted in Question 18 were Activ-

ity standardization (13 participants), Process flow

definition (10 participants), Process automation (11

participants), and Support for assigning responsibil-

ities (6 participants).

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

854

Additional Suggestions and Comments. In Ques-

tion 19, participants offered suggestions grouped into

three themes: Praise for the initiative, Awareness

and training, and Careful selection of initial de-

partments.

5 ELEMENTS OF BPM

GOVERNANCE

In the following, conclusions from the initial diagnos-

tic results are presented for each BPM Governance el-

ement.

Objectives. The governance element ”Objectives”

refers to the intentions and goals established by the or-

ganization regarding BPM initiatives. It was observed

that some participants confused business processes

with the organization’s internal processes. How-

ever, it is believed that there is a notion of busi-

ness processes in the form of procedures and work-

flows. Overall, it was concluded that most responses

align with the objectives anticipated for a BPM ini-

tiative and that the units recognize the need for Pro-

cess Management to bring efficiency and control to

their activities. The main conclusions are presented

as follows: Provide Continuous Improvement; En-

sure transparency and clarity; Facilitate management

for procedural efficiency; Identify bottlenecks; In-

crease process efficiency; Define and monitor indi-

cators; Prioritize process modeling; Create process

flow standards; Propose tools to support workflows

and activity execution; In the administrative area, re-

sponses highlighted activity and demand monitoring,

while the core area emphasized top-down determina-

tion.

Regarding sector demands (Question 2), re-

sponses from the core area primarily indicated that

they contribute directly to achieving the stipulated

goals, with 5 out of 13 responses. In the administra-

tive area, responses were divided between contribut-

ing directly to achieving the stipulated goals and con-

tributing indirectly without feeding the indicators for

the stipulated goals, each with two responses.

Roles and Responsibilities and Activities. The

”Roles and Responsibilities” element relates to the

functions and duties focused on executing BPM ini-

tiatives, while the ”Activities” element corresponds

to tasks and routines associated with the roles in-

volved in BPM initiatives. Based on these definitions,

it was observed that the organization does not have

clearly defined roles for Business Process Manage-

ment. However, individuals responsible for service

management were identified in the core sectors.

Additionally, evidence suggests that the core area

is more mature in defining and monitoring workflows

compared to the administrative area. Actions in the

core area aimed at documenting and standardizing

work procedures to ensure knowledge management

were identified. These conclusions and evidence were

drawn from responses to Question 4, with some listed

as follows: Conclusions for the Elements: 1- Roles

and Responsibilities and 2- Activities- Managers di-

rect how service management should be conducted;

Internal sector managers, general coordination, and

technical advisory roles have well-defined responsi-

bilities; The Head of the Secretariat is responsible

for unit management; The type of service or process

class determines responsibility and workflow; Defin-

ing and verifying adherence to workflows is a spe-

cific role; Workflow definitions exist in the core area;

Core area staff have well-defined responsibilities; De-

mands originate both internally and externally; There

is auditing of staff actions and expense monitoring;

Staff can be reallocated to support units based on in-

dicators; Some sectors face high demand, while some

administrative sectors lack formal assignments.

As expected, of the 6 respondents from the core

area, 5 mentioned society as the source of demands,

characterized as external demands. In the adminis-

trative area, although society was mentioned (5 re-

sponses), the majority of responses concentrated on

internal institutional sectors, with 7 responses (inter-

nal demands).

Methodological Standards and Infrastructure.

The ”Methodological Standards” element pertains to

the use of theoretical models, techniques, notations,

reference models, and standardized descriptions of

activities. Meanwhile, the ”Infrastructure” element

encompasses the technical and non-technical founda-

tions required for BPM practices, including physical

structure, software tools, staff, and other resources

used in BPM initiatives.

The conclusions regarding these two elements are

listed as follows: Conclusions for the Methodologi-

cal Standards and Infrastructure Element- Adoption

of new tools; Training on existing tools; Some areas

have procedure manuals; Use of systems as a stan-

dard work practice; Core area staff receive guidance

on procedure workflows; There is training and formal

artifacts in the core area.

Another aspect investigated in the process man-

agement diagnosis concerned the assessment of IT

support in core processes. For this purpose, an inven-

tory of systems used by the institution was conducted.

These systems were classified as either critical or sup-

porting tools/systems. To avoid identifying the insti-

tution based on the systems used, their names will not

be mentioned in this study.

Diagnosing BPM Governance: A Case Study of Facilitators, Barriers, and Governance Elements in a Hierarchical Public Instituition

855

Decision-Making Process. The ”Decision-Making

Process” element encompasses the criteria and deci-

sion boundaries for prioritizing and defining goals.

The conclusions and evidence related to this element

are listed as follows: Conclusions for the Decision-

Making Process Element - Imbalance between work-

force and operational volume. Monitoring of the sta-

tus and criticality of processes in the core area exists.

Demands are analyzed and prioritized.

There are indications of an imbalance between the

number of staff and operational capacity, suggesting

the need for a reallocation of staff based on demand.

Other criteria used for prioritization include criticality

(processes stalled for more than 100 days) and the ur-

gency of the demand, where services delivering core

outcomes are prioritized, even if they are more com-

plex.

Control and Evaluation. The ”Control and Eval-

uation” element addresses indicators, metrics, and

additional forms of monitoring for BPM initiatives.

The conclusions and evidence related to this element

are listed as follows: Conclusions for the Control

and Evaluation Element-The supervisor must be con-

tacted whenever there are issues with processes to be

completed; Monitoring of the status and criticality of

processes in the core area exists; Processes in the core

area are monitored, and full compliance is tracked;

Well-defined and monitored indicators are in place.

It was observed that participants from the core

area expressed concern about monitoring work proce-

dures. This conclusion may be related to the fact that

the core area is obligated to meet the goals established

by superior bodies. One participant mentioned: “We

are conducting meetings aimed at achieving the estab-

lished goals, striving for efficiency and transparency

in management.”

A BI tool was specifically mentioned by one par-

ticipant as an improvement to be introduced in their

area to deliver better results, as indicated in Ques-

tion 13. It is important to highlight that there are

indications that the institution’s administrative area

lacks well-defined indicators. This is evident from

responses by participants in the administrative area

emphasizing the need for standardization and clear

goals, such as: ”Definition of goals, follow-up meet-

ings to monitor results, management support.” Addi-

tionally, one participant responded ”never” to Ques-

tion 11 (”How often are the results delivered by this

unit measured?”). Regarding monitoring frequency, it

was concluded that the majority of the core area mea-

sures their results on a monthly basis.

Scope. The ”Scope” element was an additional as-

pect evaluated, encompassing knowledge of BPM ini-

tiatives within the public organization, as well as

strategies for disseminating BPM within the institu-

tion. The conclusions and evidence related to this ele-

ment are listed as follows: Conclusions for the Scope

Element- Four departments were identified with pro-

cess management initiatives;

Both administrative and core areas linked BPM to

existing tools, with some departments using BPM ini-

tiatives, yet responses also revealed a lack of aware-

ness about them; Regarding dissemination strategies:

- Training and events; - Sponsorship and partner-

ships; - New tools; - Communication; - Awareness;

- Demonstrating the practical application of BPM in

departments. Both areas provided similar responses,

such as training, better dissemination, and events to

help spread the BPM culture; The administrative area

emphasized the careful selection of the area to receive

BPM activities, while the core area stressed spreading

the BPM culture in specific locations.

It was observed that most participants lack knowl-

edge of BPM initiatives in the institution. The re-

sults demonstrate that responses included: Unaware

(4 participants), Defined an internal tool (4 partici-

pants), First contact through BPMO (2 participants),

and Have knowledge (2 participants). Additionally,

the strategies for dissemination most frequently sug-

gested by participants included: Training and events

and Communication.

6 KEY FACILITATORS AND

BARRIERS TO BPM

GOVERNANCE

As a result of the interviews with participants from

the organization, a list of facilitators and barriers was

developed, comprising 18 variables: 9 facilitators and

9 barriers.

Facilitators. The facilitators of a BPM initiative are

factors that reflect the organization’s strengths and

should be leveraged to ensure the initiative’s success.

These factors can be used to consolidate the Business

Process Management initiative and, in some cases, to

eliminate obstacles. In the context of the institution

investigated in this study, 9 facilitators were identified

and are listed as follows: Facilitators of BPM gover-

nance at the studied institution - (F1) Focus on results;

(F2) Knowledge sharing among the institution’s sec-

tors; (F3) Cooperation exists between the court’s sec-

tors and occasional training actions; (F4) Openness

to listening to people; (F5) Presence of a department

dedicated to disseminating process management; (F6)

Maturity in the core area regarding the standardiza-

tion and monitoring of workflows; (F7) Activities, de-

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

856

mands, processes in the core area and their compli-

ance are monitored, including auditing of staff actions

and expense control; (F8) People management in the

institution is guided by indicators; (F9) No significant

differences were observed between the administrative

and core areas regarding the definition of BPM.

Barriers. The barriers to a BPM initiative are factors

that reflect weaknesses or challenges to be addressed

by the organization. In the context of the institution, 9

barriers were identified, as listed as follows: Barriers

to BPM governance at the studied institution - (B1)

High operational workload; (B2) Need for improve-

ments in staff redistribution; (B3) Isolated initiatives

for workflow standardization; (B4) Redundancy of as-

signments; (B5) Lack of training and unfamiliarity

with system usage; (B6) Some sectors face high de-

mands, while others in the administrative area lack

formal assignments; (B7) Concentration of workflow

monitoring on magistrates, creating potential bottle-

necks; (B8) Need for recognition policies, team inte-

gration, and result tracking; (B9) In the administrative

area, there is a highlighted need for greater staff inte-

gration.

Based on the results, it is therefore necessary to

standardize activities, introduce new tools, train em-

ployees, and, above all, ensure that the work is guided

by producing clear and objective communication of

the measures adopted by the institution.

Suggested Actions. Based on the collected data and

team insights, a set of actions has been proposed to

enhance BPM governance by addressing barriers (B)

and leveraging facilitators (F). Each action connects

to multiple elements, reflecting key institutional dy-

namics.

Key actions include: Institutionalizing tools used

(B5, F7); Optimizing task distribution based on com-

petencies and training (B2, B4, B6, F8); Diversify-

ing and mandating relevant training (B5, F3, F8);

Expanding access to online courses and offering in-

centives for instructors (B5, F2, F3, F4); Encour-

aging recognition and competence management (B8,

F8, F9); Defining knowledge management mecha-

nisms and multipliers (B3, B5, F2, F5); Establishing

a methodology for prioritizing internal and external

demands (B3, B7, F6, F7); Encouraging staff sugges-

tions for projects (B8, F4); Improving BPMO com-

munication and dissemination (B9, F5); Organizing

BPM events and training sessions (B5, B8, F3, F5).

An analysis of these actions shows they address

most barriers, particularly operational workload (B1),

lack of training (B5), and task redistribution (B2, B6).

However, some barriers, such as workflow monitoring

concentration on magistrates (B7), require further ex-

ploration.

7 DISCUSSION

Comparison of Facilitators Across Studies. The

findings align with and extend BPM governance

literature in public organizations (Santana et al.,

2011)(Alves et al., 2014)(Jurczuk, 2021)(Doyle and

Seymour, 2020), emphasizing the interconnected

roles of facilitators and barriers.

Analyzing Facilitators reveals shared and

context-specific factors. Universal elements like

top management support and team motivation

highlight leadership’s role, while unique facilitators

reflect organizational culture.

For instance, cooperation with process clients

is specific to Santana et al. (Santana et al., 2011),

whereas Alves et al. stress financial resources and

payment schedule adherence (Alves et al., 2014).

Our study adds workflow standardization maturity

and knowledge sharing as key operational facilita-

tors, reinforcing the need for tailored BPM strategies

in public institutions.

Comparison of Barriers Across Studies. The com-

parison of barriers to BPM governance reveals both

common and context-specific challenges. While re-

sistance to change and lack of methodology are

widespread issues, other barriers stem from unique

organizational constraints.

A key barrier is resistance to change (Santana

et al., 2011; Alves et al., 2014; Doyle and Seymour,

2020; Jurczuk, 2021), linked to cultural norms and

disruption fears. Another is the lack of formalized

methodologies (Alves et al., 2014; Jurczuk, 2021),

stressing the need for standardized BPM frameworks.

Additional barriers include insufficient BPM

training (Santana et al., 2011; Doyle and Sey-

mour, 2020), bureaucracy (Santana et al., 2011), and

competition with non-BPM activities (Alves et al.,

2014). Our study adds high operational workload

and workflow monitoring on magistrates, reflecting

judicial system constraints.

The alignment of these barriers highlights the

need for tailored solutions, such as automation for

workload challenges and governance adjustments to

integrate BPM into strategic planning.

8 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

This document presented the workshop results on

BPM practices and competencies within the institu-

tion, conducted with 13 staff members from core and

administrative areas.

Diagnosing BPM Governance: A Case Study of Facilitators, Barriers, and Governance Elements in a Hierarchical Public Instituition

857

The following points were observed: Training

was highly requested by participants: Greater dis-

semination of BPM concepts, improved use of ex-

isting tools, and better result delivery. Need for

adopting new tools: It remains unclear whether new

tools are needed or if better training on current tools

would suffice. Institutionalizing internal communica-

tion tools is also necessary. Contributions of BPMO

to the institution: Standardizing process flows to

prevent task duplication and introducing workflow

support tools. Core areas appear more mature than

administrative areas: Core areas show greater stan-

dardization and workflow monitoring. Establishing

a methodology for prioritizing service execution:

Developing a priority-setting methodology and ensur-

ing accessibility of the prioritization table. Interest

in recognition policies and integration of staff: De-

mand for recognition policies, team integration, re-

sults tracking, and staff reallocation improvements.

Future work includes analyzing organizational

culture to assess its influence on BPM adoption and

identify ways to enhance integration.

REFERENCES

Alves, C., Valenc¸a, G., and Santana, A. F. (2014). Un-

derstanding the factors that influence the adoption of

bpm in two brazilian public organizations. In Interna-

tional Workshop on Business Process Modeling, De-

velopment and Support, pages 272–286. Springer.

Beerepoot, I., Di Ciccio, C., Reijers, H. A., Rinderle-Ma,

S., Bandara, W., Burattin, A., Calvanese, D., Chen,

T., Cohen, I., Depaire, B., et al. (2023). The biggest

business process management problems to solve be-

fore we die. Computers in Industry, 146:103837.

de Boer, F. G., M

¨

uller, C. J., and ten Caten, C. S. (2015).

Assessment model for organizational business process

maturity with a focus on bpm governance practices.

Business Process Management Journal, 21(4):908–

927.

Doebeli, G., Fisher, R., Gapp, R., and Sanzogni, L. (2011).

Using bpm governance to align systems and practice.

Business Process Management Journal, 17(2):184–

202.

Doyle, C. and Seymour, L. F. (2020). Governance chal-

lenges constraining business process management:

The case of a large south african financial services

corporate. In Responsible Design, Implementation

and Use of Information and Communication Technol-

ogy: 19th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business,

e-Services, and e-Society, I3E 2020, Skukuza, South

Africa, April 6–8, 2020, Proceedings, Part I 19, pages

325–336. Springer.

Dutra, D. L., dos Santos, S. C., and Santoro, F. M.

(2022). Erp projects in organizations with low matu-

rity in bpm: A collaborative approach to understand-

ing changes to come. In Proceedings of the 24th Inter-

national Conference on Enterprise Information Sys-

tems - Volume 2: ICEIS, pages 385–396. INSTICC,

SciTePress.

Harmon, P. and Trends, B. P. (2010). Business process

change: A guide for business managers and BPM and

Six Sigma professionals. Elsevier.

Hernaus, T., Bosilj Vuksic, V., and Indihar

ˇ

Stemberger,

M. (2016). How to go from strategy to results? in-

stitutionalising bpm governance within organisations.

Business Process Management Journal, 22(1):173–

195.

Jurczuk, A. (2021). Barriers to implementation of business

process governance mechanisms. Engineering Man-

agement in Production and Services, 13(4):22–38.

Kirchmer, M. (2009). Business process governance for

mpe. High Performance Through Process Excellence:

From Strategy to Operations, pages 69–84.

Mbengo, L. and Lumka, T. P. S. (2024). Towards un-

derstanding the hindering factors of business process

management adoption in state-owned enterprises: A

scoping review. In 2024 Conference on Informa-

tion Communications Technology and Society (IC-

TAS), pages 161–167. IEEE.

Rosemann, M. and vom Brocke, J. (2014). The six core

elements of business process management. In Hand-

book on business process management 1: introduc-

tion, methods, and information systems, pages 105–

122. Springer.

Santana, A. F. L., Alves, C. F., Santos, H. R. M., and

de Lima Cavalcanti Felix, A. (2011). Bpm gov-

ernance: an exploratory study in public organiza-

tions. In International Workshop on Business Pro-

cess Modeling, Development and Support, pages 46–

60. Springer.

Santos, S., Xavier, M., and Ribeiro, C. (2024). Business

process improvements in hierarchical organizations:

A case study focusing on collaboration and creativ-

ity. In Proceedings of the 26th International Confer-

ence on Enterprise Information Systems - Volume 2:

ICEIS, pages 721–732. INSTICC, SciTePress.

Syed, R., Bandara, W., French, E., and Stewart, G. (2018).

Getting it right! critical success factors of bpm in the

public sector: A systematic literature review. Aus-

tralasian Journal of Information Systems, 22:1–39.

Valenca, G., Alves, C. F., Santana, A. F. L., de Oliveira, J.

A. P., and Santos, H. R. M. (2013). Understanding the

adoption of bpm governance in brazilian public sector.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

858