Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR)

Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping

Bethany K. Bracken

1

, Phillip C. Desrochers

1

, Ian McAbee

1

, Nicolette M. McGeorge

1

, Susan Latiff

1

,

Bradly T. Stone

1

, Dan T. Duggan

1

, Corinne Cather

2

and A. Eden Evins

2

1

Charles River Analytics, Inc., Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.

2

Center for Addiction Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, U.S.A.

Keywords: Virtual Reality (VR), Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Vaping Cessation, Usability Study, Human

Factors, Patient Safety, Digital Therapeutics (DTx).

Abstract: Nicotine vaping is a global problem. Limited vaping cessation interventions are available; and current

treatments have limited accessibility due to systemic barriers to care (e.g., scarcity of treaters). Digital

therapeutics (DTx) can reduce these barriers. We have embedded standard cognitive behavioral therapy

(CBT) content into virtual reality (VR) to create a VR-based app focused on vaping cessation: Novel, On-

demand VR for Accessible, Practical, and Engaging therapy (NO VAPE). NO VAPE allows users to practice

CBT skills gained in traditional therapy through an accessible, immersive, and engaging platform. Our

ultimate goal is to conduct a full clinical trial to test whether NO VAPE motivates greater intervention

adherence and satisfaction. To prepare, we conducted a usability study with N = 6 young adults who currently

vape, aiming to evaluate safety, usability, and overall enjoyment of NO VAPE. We categorized errors into

categories in ascending severity from minor usability errors to safety violations. There were no safety

violations by any participants providing evidence that the app is low-risk and safe (from a software use

perspective, not a substance use perspective). Participant reported high levels of enjoyment, said they would

like to use NO VAPE again, and did not experience symptoms of simulator sickness. We also identified

multiple software bugs we are now addressing.

1 INTRODUCTION

Vaping is an increasing problem around the world. In

2017-2018, the prevalence of vaping was 2.4% across

Europe. The highest prevalences were 7.2% in

England, 4.3% in France, and 4.1% in Greece (Gallus

et al., 2023). In 2019 in Asia, the highest prevalence

was 32.2% in Indonesia (Ko et al., 2024). In 2022, in

the US, an estimated 2.5M youths reported vaping.

Vaping is increasingly being used to assist in smoking

cessation (McNeill et al., 2021); however, vaping—

although likely less harmful than smoking (Abafalvi

et al., 2019; Levy et al., 2021)—is associated with

multiple adverse reactions, such as oral health

problems, cardiac disorders, lung injury, respiratory

disorders, and gastrointestinal disorders (Hammond,

2019; Irusa et al., 2020; McNeill et al., 2021;

Traboulsi et al., 2020). To help individuals attempt to

quit or maintain abstinence from vaping, in addition

to drug therapy, multiple psychological therapies

exist. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), teaches

individuals to recognize the events that trigger

craving; their mental, physical, and behavioral

reactions to the events; and provides training on

strategies to resist cues and handle stressful situations

without vaping.

Traditional vaping cessation interventions have

limited accessibility due to systemic barriers to care,

including scarcity of treaters and personal factors

(e.g., lack of transportation). There are several

potential routes to maximize reach and efficacy of

current therapies. Growing evidence suggests that

digital and technology-based therapies improve

various mental health and substance use disorder

outcomes, as a standalone treatment or augmentation

strategy for in-person treatment (Graham et al., 2021,

2024). VR technology in particular may allow

individuals to practice CBT techniques to cope with

symptoms (e.g., cravings) and situations (e.g., stress

at work) in an immersive environment that may be

more evocative and effective than standard CBT for a

wide range of mental health and substance use

882

Bracken, B. K., Desrochers, P. C., McAbee, I., McGeorge, N. M., Latiff, S., Stone, B. T., Duggan, D. T., Cather, C. and Evins, A. E.

Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR) Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping.

DOI: 10.5220/0013350000003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 882-889

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

disorders (Gao et al., 2013). VR-delivered substance

use disorder treatments have been developed to

address multiple substances (e.g., nicotine, alcohol,

and marijuana (Loria, 2016)). People who

successfully develop relapse-avoidance strategies in

VR do translate those strategies to the real world

(Bellum, 2014). Presentation of smoking cues in VR

(García-Rodríguez et al., 2012) or smoking a virtual

cigarette (García-Rodríguez et al., 2013) increases

craving and heart rate similar to real-world stimuli

(Ferrer-Garcia et al., 2012). The use of VR may also

make interventions more engaging (Gao et al., 2013);

participants in one study reported enjoying a VR

game designed for quitting vaping and said they

would recommend it to friends (Weser & Hieftje,

2020), demonstrating its feasibility, satisfaction, and

salience. Technological interventions to aid quitting

can embed therapeutic content into VR (Lee et al.,

2004; Lee et al., 2003), thereby allowing participants

to practice resisting cues to use substances in a safe

environment (Metcalf et al., 2018).

Even though this research is encouraging,

currently, no engaging, immersive intervention exists

for vaping cessation therapy, and there are no

published controlled clinical trials to our knowledge

testing the efficacy of embedding CBT content into

VR to increase success at achieving vaping

abstinence. To address this need, we built Novel, On-

demand VR for Accessible, Practical, and Engaging

therapy (NO VAPE). In the next Phase of the project

we will conduct a pilot controlled clinical trial of its

efficacy for vaping abstinence outcomes. The project

presented here is thus a usability study, NOT an

efficacy study or clinical trial. In preparation for this

clinical trial, we conducted a preliminary human

factors usability study to assess its ease of use,

engagement, and safety, including not inducing

simulator sickness (FDA, 2016). The usability

study’s goals were to:

1 Determine if there are usability issues that could

increase risks to users (e.g., walking into a wall)

to unacceptable levels, and test whether the NO

VAPE system can be used by representative

users under simulated conditions without

producing patterns of failure that could result in

negative impact to the user.

2 Evaluate effectiveness of instructional materials.

3 Determine if the potential for critical errors that

would or could result in high-severity outcomes

to the user (from a software-use perspective, not

a substance use perspective) have been

mitigated.

4 Provide recommendations for the device,

instructional materials, and labeling that may

mitigate the probability of use errors (usability-

and safety-related).

5 Assess the navigation of the interface and

identify areas for improvement.

2 METHODS

Participants evaluated NO VAPE during one-on-one

sessions lasting up to three hours. Participants were

paid $25 per hour in gift cards (e.g., Amazon, Visa)

to encourage participants not to rush and to take their

time in the VR environments. Each participant

completed 11 scenarios (a tutorial and all 10

simulated vaping scenarios). First, they completed the

tutorial, which provided instruction on how to move

around the VR environment and interact with items

around them. Then they completed the 10 vaping

scenarios in randomized order, including scripted

activities and CBT content. The environments

included: (1) a bedroom in the morning where they

decide whether to take their vape with them when

they leave, (2) a kitchen where they get ready for the

day, (3) a coffee shop where someone asks them to

watch their bag then the person goes into the

bathroom and vapes, (4) a classroom where friends

ask them to go to lunch (where they will be vaping),

(5) a work or school bathroom where someone in the

next stall is vaping, (6) a car ride with a friend who is

vaping, (7) a stressful day at work in an office

environment, (8) a party where people are vaping and

they must navigate an awkward conversation, (9) a

corner store where they previously bought vapes, and

(10) a living room at home alone at night. See Figure

1 for a screenshot of one of the scenarios (the

classroom scenario). Participants were encouraged to

“think aloud” during their interactions in each

environment to express what they were thinking,

doing, had questions about, etc.

Figure 1: Screenshot from the classroom scenario.

As participants completed tasks within the VR

environment, we mirrored the screen in the VR

Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR) Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping

883

headset onto a laptop to allow experimenters to view

and record (screen capture recording) what the

participant was seeing in the VR environment. The

video recording allowed review and coding of user

interactions and activities in the VR environment (e.g.,

what task they were struggling to complete and why),

and enabled coders to hear participants’ comments in

context. Two “raters” recorded completion of each task

in real time as the participant progressed through tasks

in the environment. In the case of a mismatch in ratings

between the two experimenters, a third rater reviewed

the video of the experimental session and served as the

“tie breaker.” Task performance was assessed based on

task completion success and the number and type of

use-based errors.

Table 1: Task Hierarchy for the bathroom scenario (a

breakdown of the tasks required to complete the scenario).

Task Task X Task X.X Task X.X.X

1

Read “Reach for

Va

p

e”

Respond

2 Read “Plan” Respon

d

3 Read “Sit Down”

Navigate to

Toilet

4

Read “Check

Phone”

Respond

5 Read “Res

p

onse” Res

p

on

d

6 Read “Thin

k

” Click Next

7

Read “How to

Rewar

d

”

Respond

7.1

Deep

Breathing

Respond

7.2 Meditation

Listen to

exercise

7.3

Muscle

Relaxation

Respond

8 Read “Check In” Res

p

on

d

9

Read “Deal with

Boredom”

Respond

10

Read “Wash

Hands”

Navigate to

Sin

k

10.1

Place Hands

Under Sin

k

Participants who had previously expressed

interest in studies about reducing or quitting vaping

were contacted to determine whether they were

interested in learning more about this study.

Interested individuals were screened by phone for

eligibility. Inclusion criteria were: age 18 years or

older, reported vaping nicotine daily or near daily in

the prior ≥ 3 months, nicotine dependence

operationalized by a score of ≥4 (at least mild

dependence) on the 10-item E-cigarette Dependence

Inventory (ECDI) (Piper et al., 2020; Vogel et al.,

2020), self-reported interest in quitting vaping, at

least one prior experience with using a VR program,

ability to understand study procedures and read and

write in English, and vision corrected to within

20/500 bilaterally.

To identify critical tasks, we conducted a

Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA), a task

decomposition method that produces a hierarchy of

activities users must do within NO VAPE and the

associated necessary conditions (i.e., required

subtasks to meet goals) (Diaper & Stanton, 2003).

HTA establishes conditions when sub-tasks should be

carried out to meet goals. See Table 1 for an example

Task Hierarchy required to complete the bathroom

scenario. We used the result of this HTA to identify

errors (e., inability to complete a task).

For each scenario, we categorized errors into the

following categories: (1) Slips: occur as the result of

minor errors of execution, but the participant was able

to recover without help from the experimenter, (2)

Lapses: occur when a person could not complete a

task without a hint by the experimenter (we let them

fail 3 times before providing a hint), (3) Mistakes:

occur when participants did not complete the task

even with the help of the experimenter (note that these

were mostly software errors when we had to restart

the software), and (4) Violations: occur when actions

deviate from safe procedures, standards, or rules,

whether deliberate or erroneous. Importantly, there

were not Violations by any participants in any

scenario providing evidence that the app is low-risk

and safe to use.

Average prevalence of each error was calculated

as a percentage of all tasks and averaged across

participants. We counted errors for top-level tasks.

For example, if there are multiple steps to complete a

task, we count the entire procedure as a single task.

As a specific example, in the bathroom scenario, to

fully complete Task 8, the participant had to complete

the top-level task (8) as well as at least one of the

second level tasks (8.1, 8.2, or 8.3) (see Table 1).

Participants completed the following

questionnaires: Demographics, E-cigarette

Dependence Inventory (ECDI)) (Piper et al., 2020;

Vogel et al., 2020), Vaping History, Presence (Witmer

& Singer, 1998), Simulator Sickness (Lin et al., 2002),

Engagement, Enjoyment, Interactivity, and Immersion

(E

2

I) (Lin et al., 2002), Post Experience (adapted from

(Usoh et al., 2000)), Post Evaluation Interview.

3 RESULTS

Participants included 6 adults (3 female; we did not

collect race/ethnicity information) aged 20-31

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

884

(average age = 24). All reported having some

experience with VR (i.e., previously used VR at least

five times for five minutes). 50% of participants (3/6)

reported also currently smoking tobacco.

Table 2 shows prevalence of each error type in

each scenario. For example, of the 8 tasks in the

tutorial, participants slipped an average of 10% of the

time, ranging from 0 slips to 2 slips per participant

across the full tutorial level. Participants committed

lapses 8% of the time, ranging from 0-1 lapse per

participant. There were no mistakes in the Tutorial.

Table 2: For each scenario, we calculated the percentage of

each type of error for each participant, then averaged across

participants. We show the number of tasks as a reference as

each scenario had differing numbers of major tasks to

complete (see Table 1 for an example of a task hierarchy).

Scenario

#

Tasks

% Slips

(Range)

% Lapses

(Range)

%

Mistakes

(Range)

Tutorial 8 10%

(

0-2

)

8%

(

0-1

)

0%

Bathroo

m

17 2%

(

0-1

)

0% 0%

Bedroo

m

22 7%

(

0-3

)

0% 0%

Café 21 2% (0-2) 0% 1% (0-1)

Ca

r

19 5% (0-1) 0% 5% (0-1)

Classroom 21 5%

(

0-1

)

0% 0%

Kitchen 16 6%

(

0-2

)

0% 1%

(

0-1

)

Living

Room

32 4% (0-3) 1% (0-1) 2% (0-1)

Part

y

26 3%

(

0-2

)

0% 1%

(

0-1

)

Store 29 5%

(

0-2

)

3%

(

0-2

)

0%

Wor

k

36 2%

(

0-2

)

0% 1%

(

0-1

)

E-Cigarette Dependence Index scores ranged

from 8 to 16 (mean = 11.8) consistent with moderate

dependence (Foulds et al., 2015). Daily use varied

from 0 to 5-9 times (50-90 mins). All participants

reported vaping within 60 minutes of waking when

able to vape freely. Half of participants reported

awakening at night to vape at least twice a week. All

participants reported finding it very hard to quit and

finding it hard to keep from vaping in places they are

not supposed to. With all participants having strong

cravings to vape, all noted that they become more

irritable when they are unable to use an electronic

cigarette and 4/6 felt nervous, restless or anxious

when they could not use an electronic cigarette.

Average age to begin vaping was 20.1 years. Most

common reasons for initiation was peer pressure and

having family/friends who vape. Participants had

vaped 3.5 years on average, between 0.14 and 1

cartridge per day. The Crave brand was used by 4/6

participants. The most common reason for wanting to

quit were concerns about future health problems

followed by financial reasons. All participants had

tried to quit vaping within the past year; half had quit

vaping for at least 24 hours with an average cessation

period of 27.1 days. Two participants reported having

used nicotine gum, 1 participant reported use of

bupropion, and 1 participant reported using

medication other than bupropion or nicotine and/or

herbal treatments.

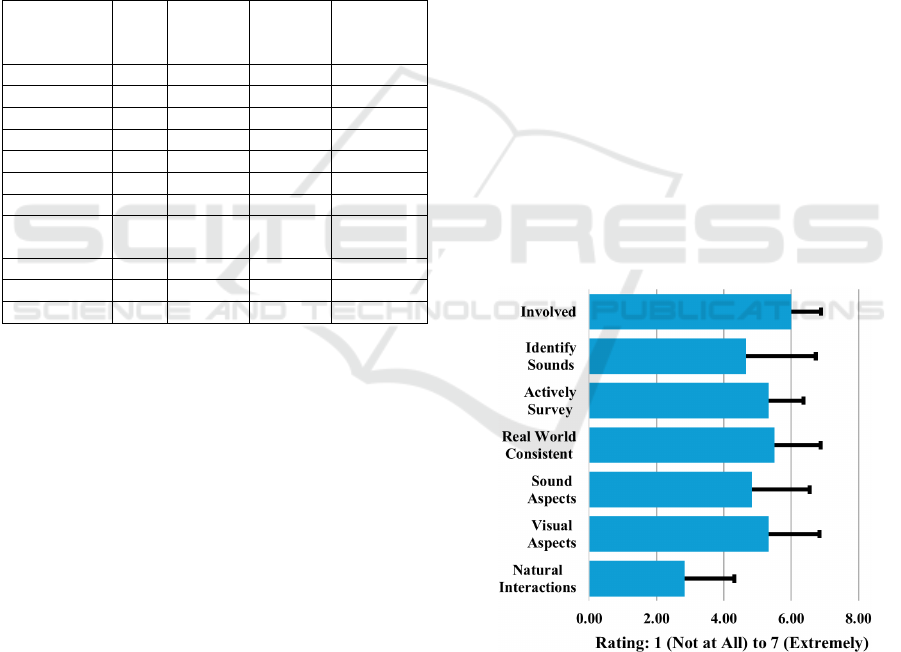

In the Presence Questionnaire, participants

characterized their experience in the virtual

environment, rating their experience on a scale of 1-

7, from 1 (bounds related to low presence) to 7

(bounds related to high presence), across seven

questions (see Figure 2). Participants noted their

interactions in the environment felt less natural (see

discussion), with a mean of 2.83 (1 – “Completely

artificial” to 7 – “Completely natural”). However,

they felt somewhat involved in the visual

(mean=5.33) and auditory (mean=4.83) aspects of the

environment on a scale of 1 being “Not at all” to 7

being “Completely”. Experiences in the simulation

were consistent with those in the real world (mean =

5.5 (1 – “Not at all” to 7 – “Completely”)).

Completeness of the ability to visually survey the

environment was good (mean=5.33) (1 – “Not at all”

to 7 – “Completely”). Participants were somewhat

able to successfully identify sounds (mean = 4.67 (1

– “Not at all” to 7 – “Completely”)). Participants felt

involved in the virtual experience with a mean of 6 (1

– “Not involved” to 7 – “Completely engrossed”).

Figure 2: Presence questionnaire results.

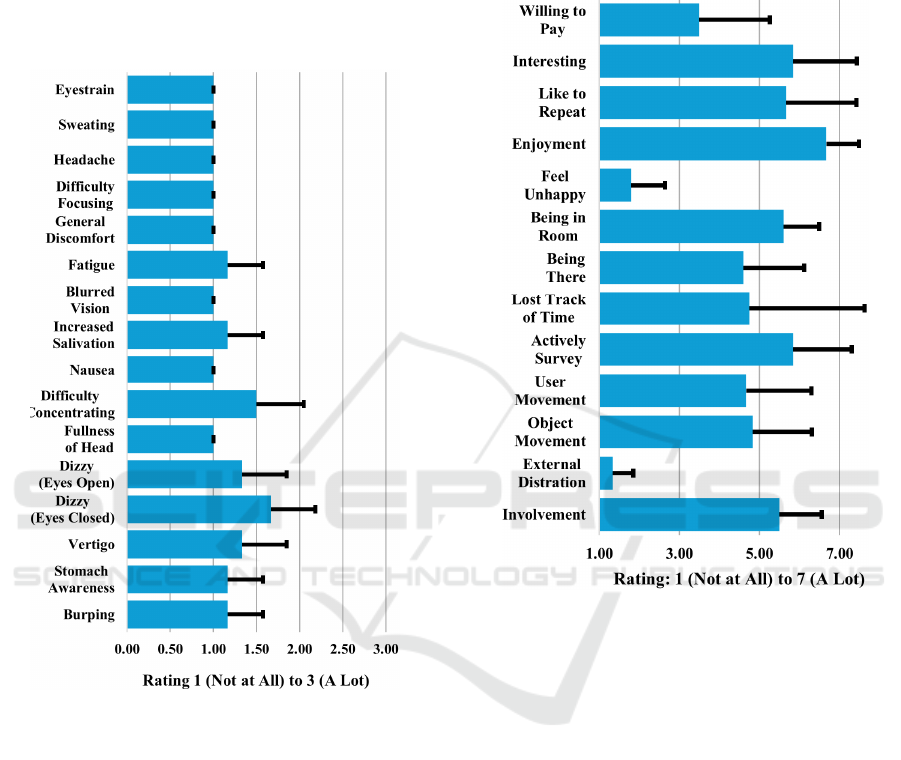

For the Simulator Sickness questionnaire,

participants were asked to rate on a scale of 1-3 (1-

“Not at all” to 3 – “a lot”) the degree to which they

experienced sixteen conditions: general discomfort,

fatigue, headache, eyestrain, difficulty focusing,

increased salivation, sweating, nausea, difficulty

Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR) Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping

885

concentrating, fullness of head, dizzy (eyes open),

dizzy (eyes closed), vertigo, stomach awareness, and

burping. The mean across all conditions was 1.15.

The only negative symptom that participants

experienced from the simulation was increased

eyestrain (mean=1.7). Sweating (mean=1.5),

headaches (mean=1.33) and difficulty focusing

(mean=1.33) were felt but not strongly. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Simulator Sickness questionnaire results.

For the Engagement, enjoyment, interactivity,

and immersion questionnaire, participants were asked

to respond to 12 questions on a scale of 1-7 (1- “Not

at all” to 7 – “A lot”). Most participants were attracted

to the visual scenes within the application with a

mean of 5.5 and noise outside the simulation was not

an issue for most (mean=1.33). Feelings were mixed

about the matching of the real world to the virtual

environment with participants feeling an average of

somewhat "being there" in the virtual environment

(mean=4.6). Overall, moving objects within the

virtual space was somewhat compelling (mean=4.83)

as was moving oneself through the space

(mean=4.67). Time tracking varied across

participants with two participants losing track of time

entirely, and one not at all (mean=4.75). All

participants were not unhappy when the simulation

was over (mean=1.8). They would likely repeat the

experience (mean=5.6) and found it interesting

(mean=5.83), however they would not be likely to

pay for it. Results are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Engagement, enjoyment, interactivity, and

immersion questionnaire (E2I) results.

Participants answered a Post Experience

Questionnaire to probe for additional factors related

to VR presence and physiological effects on a scale

of 1 (seemingly artificial) to 7 (like being in the real

world) For presence-related questions, participants

felt mixed about the simulation accurately

representing their normal experiences of being in a

place (mean=5). The virtual environment did not feel

completely like a "reality" to most (mean=4.17) and

their sense of being fully immersed was average.

Participants recalled simulated images both as images

they saw and places they visited (mean of 4.17 on a

scale of 1 - “Simulated images” to 7 - “Somewhere

that I visited”). Their sense of being in the simulated

environment was slightly greater than being

elsewhere with a mean of 5.17 (1 – “Being

elsewhere” to 7 – “Being in the simulated

environment”). Participant memory of the virtual

space was somewhat vivid as it related to places they

had visited that day (mean of 4 on a scale of 1 – “Not

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

886

at all” to 7 – “Very much so”). Most participants did

not pay attention to events in the real world during

their time in the simulation (mean=2.33) and most

were completely focused on the tasks (mean=6.33).

Participants also rated the degree to which they

experienced physiological effects during NO VAPE

use, on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“almost all

the time”). None of the participants experienced

strong feelings of nausea (mean=1.2), dizziness

(mean=1.2) or headaches (mean=1.3). However,

there was some degree of mild eye strain noted

(mean=2.2).

After the session, we asked open-ended questions

to understand the opinions of participants.

Participants did note several areas of improvement in

the simulation. The meditation room was not well-

received by several participants who noted it needed

visual and audio improvements (“Immersion breaks

for meditation”, “More detail in meditation room

would be nice.”). The placement of text messages in

the space were difficult for some users to view, with

the text being too close or running into the walls

during some scenarios. Some of the interactions

proved challenging for participants and they would

have liked to become more familiar with the controls

before they began the scenarios (“was looking at

hands for feedback on what each control did”,

“teleportation was sometimes hard”). Some of the

options were difficult to select and there was

confusion about which objects could be interacted

with. Inconsistent interaction mechanics pulled some

of the participants out of the experience and specific

issues with object interaction broke the immersion

(“immersion stronger in some parts than others”).

However, overall, feedback was positive.

Participants felt that scenarios were generally

accurate, immersive, relatable and valuable

(“Scenario content was accurate”, “Felt real/actual

situations that happen”). They really enjoyed the

interaction-based approach once they got used to the

controls and how to navigate the space. They noted

that the activities in the scenarios reinforced good

habits. The highlighting was a very effective means

of guiding users through tasks and when not present,

participants faltered. Participants liked the options

they were given for where they could place objects

(“multiple options to hide the vape was good”).

Participants felt that the system would be safe for use

at home, and some viewed it as an empowering

therapeutic tool for quitting (“more empowered to

quit”). They “could see it as a therapeutic tool.”, felt

"more empowered to quit", and “didn't think of it as

therapy until after.”

4 CONCLUSIONS

This preliminary study addressed all the initial goals

outlined in Section 1. First, we determined that there

are no usability issues that could increase risks to

users to unacceptable levels (from a software use

perspective, not a substance use perspective), and that

the NO VAPE System can be used by representative

users under simulated conditions without producing

patterns of failure that could result in negative impact

or injury to the user. Across all of our participants,

and in all of our scenarios, there were zero deviations

from safe procedures (i.e., Violations).

Second, we evaluated the effectiveness of the

instructional materials for teaching users how to

interact with the system without frustration. The

Tutorial scenario was always the first scenario that

participants completed, and the goal of this scenario

was to teach participants how to interact with the

application (e.g., how to navigate from one place to

another, open cupboards or drawers, pick up items

and put them into a bag, interact with non-player

characters (NPCs), eat and drink, etc.). As expected,

participants committed more errors in the tutorial

(slips an average of 10% of major tasks and lapses an

average of 8% of major tasks) than the later scenarios

as they were not yet familiar with how to navigate the

software. However, one weakness was that

participants had difficulty interacting with the

environment (found interactions to be unnatural).

This information allowed us to review videos and task

completion information to identify where interactions

were difficult for participants (e.g., interacting with

the phone), allowing us to fix these issues.

Third, we determined that the potential for

critical errors that would or could result in high-

severity outcomes to the user have been mitigated to

the extent reasonable or possible through the design

of the device and instructional materials. We

previously completed a related VR application

focused on smoking cessation (called Constructed

Environments for Successfully Sustaining

Abstinence Through Immersive and On-Demand

Treatment; CESSATION), and conducted a full set of

human factors studies on that app. During that work,

we discovered that the errors with high severity

outcomes were related to using the VR itself. These

included potentially walking physically throughout

the environment rather than virtual teleporting,

resulting in a potential to walk into a wall or other

furniture, and “forgetting” that they were in VR and

potentially trying to physically sit on a chair that was

not present outside of the VR world. That study

resulted in the production of a similar Tutorial

Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR) Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping

887

environment in CESSATION. We used those lessons

when building NO VAPE. The results of the current

usability evaluation indicate that we were successful

in mitigating any potential high-severity outcomes

through this Tutorial material.

Fourth, by analyzing the errors that were made

whenever a participant had trouble with or could not

complete a task, we were able to collate information

about each error, and provide recommendations for

VR app refinement, including to improve

instructional materials (e.g., participants wanted to

receive additional information about the trivia

question content), and labeling to mitigate the

probability of use errors (usability- and safety-related

content). Most of the Mistakes were actually a result

of software errors that would not allow the participant

to play further through the level. For example in the

living room scenario, sometimes the participant

accidentally dropped the TV remote onto the couch

before they turned on the TV. The remote disappeared

and they could not retrieve it again. This prevented

them from turning on the TV, preventing them from

completing any task further into the scenario. As

planned, this usability study has allowed us to fix

these identified software errors.

Fifth, we assessed the navigation of the interface

and identify areas for improvement. During the study,

participants were encouraged to use the “think aloud”

method to talk about what they were doing in the

environment (the experimenter could also view

participant interactions on a mirrored screen). This

allowed us to collect subjective comments from

participants (e.g., “ooh, I like the nature sounds” and

“this room feels really sterile” during the meditation

practice in a separate meditation room). We collated

all of the participant comments that occurred

naturally during the experiment as well as the

responses to the post-evaluation interview, and

compiled a list of recommendations that will inform

refinement of the NO VAPE app prior to conduct of

the planned clinical study.

One limitation to this work is the number of

participants, and the fact that all participants were

over 18 years old, even though we plan to use it with

participants 16+. We are now working to enroll

additional participants for a target of N=15 who are

18+ and N=15 who are 16-17.

We believe that the results of this preliminary

usability evaluation indicate that once we implement

the recommended software and scenario content

improvements, we will have a safe and user-friendly

VR application to use in our clinical study. The only

controlled trial to date of an intervention for cessation

of vaped nicotine is a parallel, two-group, double-

blind, individually randomized clinical trial of “This

is Quitting (TIQ)”, a free, anonymous texting app,

that incorporates messages from people who have

attempted to or successfully quit e-cigarettes. This

study included 2588 young adults aged 18-24.

Participants were significantly more likely to quit

vaping when receiving TIQ than without intervention

(24.1% versus 18.6%; p<0.001) (Graham et al., 2021,

2024). However, text messaging is not immersive,

provides no opportunity for ecologically valid

practice of resisting cravings, and may not be

engaging across continuous use. Therefore, in the

next phase of this work, we will conduct a single-

blind, parallel group, randomized clinical trial in 90

non-smoking, nicotine-dependent people, age 16+,

who want to quit vaping. We hypothesize that those

assigned to NO VAPE combined with a 12-session

vaping cessation CBT program (experimental group)

will have a higher rate of 4-week continuous

abstinence at the end of 12 weeks treatment than those

assigned to CBT alone (control group). If successful,

this will provide clinical evidence of real-world

outcomes and efficacy of NO VAPE.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants in the trial for their time and

input. Research reported in this publication was

supported by the National Institute On Drug Abuse of

the National Institutes of Health under Award

Number R44DA059018. The content is solely the

responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily

represent the official views of the National Institutes

of Health.

REFERENCES

Abafalvi, L., Pénzes, M., Urbán, R., Foley, K. L., Kaán, R.,

Kispélyi, B., & Hermann, P. (2019). Perceived health

effects of vaping among Hungarian adult e-cigarette-

only and dual users: A cross-sectional internet survey.

BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–10.

Bellum, S. (2014). Virtual Reality and Drug Abuse

Treatment. NIDA for Teens. https://teens.drugabuse.

gov/blog/post/virtual-reality-and-drug-abuse-treatment

Diaper, D., & Stanton, N. (2003). The handbook of

task analysis for human-computer interaction.

https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Eudd

OAMeI5sC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=the+handbook+for

+task+analysis&ots=7M0qGFaefd&sig=HGOX2pLK

hUVXRFYBGsyZdhwKNWI

Ferrer-Garcia, M., Garcia-Rodriguez, O., Pericot-Valverde,

I., Yoon, J. H., Secades-Villa, R., & Gutierrez-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

888

Maldonado, J. (2012). Predictors of smoking craving

during virtual reality exposure. Presence: Teleoperators

and Virtual Environments, 21(4), 423–434.

Food and Drug Administration. (2016). Applying Human

Factors and Usability Engineering to Medical

Devices [Guidance]. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-

information/search-fda-guidance-documents

Foulds, J., Veldheer, S., Yingst, J., Hrabovsky, S., Wilson,

S. J., Nichols, T. T., & Eissenberg, T. (2015).

Development of a questionnaire for assessing

dependence on electronic cigarettes among a large

sample of ex-smoking E-cigarette users. Nicotine &

Tobacco Research, 17(2), 186–192.

Gallus, S., Lugo, A., Stival, C., Cerrai, S., Clancy, L.,

Filippidis, F. T., Gorini, G., Lopez, M. J., López-Nicolás,

Á., & Molinaro, S. (2023). Electronic cigarette use in 12

European countries: Results from the TackSHS survey.

Journal of Epidemiology, 33(6), 276–284.

Gao, K., Wiederhold, M. D., Kong, L., & Wiederhold, B.

K. (2013). Clinical experiment to assess effectiveness of

virtual reality teen smoking cessation program.

García-Rodríguez, O., Pericot-Valverde, I., Gutiérrez-

Maldonado, J., Ferrer-García, M., & Secades-Villa, R.

(2012). Validation of smoking-related virtual

environments for cue exposure therapy. Addictive

Behaviors, 37(6), 703–708.

García-Rodríguez, O., Weidberg, S., Gutiérrez-Maldonado,

J., & Secades-Villa, R. (2013). Smoking a virtual

cigarette increases craving among smokers. Addictive

Behaviors, 38(10), 2551–2554.

Graham, A. L., Amato, M. S., Cha, S., Jacobs, M. A.,

Bottcher, M. M., & Papandonatos, G. D. (2021).

Effectiveness of a Vaping Cessation Text Message

Program Among Young Adult e-Cigarette Users:

A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal

Medicine, 181(7), 923–930. https://doi.org/10.1001/

jamainternmed.2021.1793

Graham, A. L., Cha, S., Jacobs, M. A., Amato, M. S.,

Funsten, A. L., Edwards, G., & Papandonatos, G. D.

(2024). A vaping cessation text message program for

adolescent e-cigarette users: A randomized clinical

trial. Jama, 332(9), 713–721.

Hammond, D. (2019). Outbreak of pulmonary diseases

linked to vaping. In Bmj (Vol. 366). British Medical

Journal Publishing Group.

Irusa, K. F., Vence, B., & Donovan, T. (2020). Potential

oral health effects of e-cigarettes and vaping: A review

and case reports. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative

Dentistry, 32(3), 260–264.

Ko, K., Ting Wai Chu, J., & Bullen, C. (2024). A Scoping

Review of Vaping Among the Asian Adolescent

Population. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health,

36(8), 664–675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539524

1275226

Lee, J. H., Ku, J., Kim, K., Kim, B., Kim, I. Y., Yang, B.-H.,

Kim, S. H., Wiederhold, B. K., Wiederhold, M. D., &

Park, D.-W. (2003). Experimental application of virtual

reality for nicotine craving through cue exposure.

CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(3), 275–280.

Lee, J., Lim, Y., Graham, S. J., Kim, G., Wiederhold, B. K.,

Wiederhold, M. D., Kim, I. Y., & Kim, S. I. (2004).

Nicotine craving and cue exposure therapy by using

virtual environments. CyberPsychology & Behavior,

7(6), 705–713.

Levy, D. T., Tam, J., Sanchez-Romero, L. M., Li, Y., Yuan,

Z., Jeon, J., & Meza, R. (2021). Public health

implications of vaping in the USA: The smoking and

vaping simulation model. Population Health Metrics,

19(1), 1–18.

Lin, J.-W., Duh, H. B.-L., Parker, D. E., Abi-Rached, H., &

Furness, T. A. (2002). Effects of field of view on

presence, enjoyment, memory, and simulator sickness

in a virtual environment. Virtual Reality, 2002.

Proceedings. IEEE, 164–171.

Loria, K. (2016). Therapists have created a virtual reality

heroin cave in an attempt to help addicts. Tech Insider.

McNeill, A., Brose, L., Calder, R., Simonavicius, E., &

Robson, D. (2021). Vaping in England: An evidence

update including vaping for smoking cessation,

February 2021. Public Health England: London, UK,

1–247.

Metcalf, M., Rossie, K., Stokes, K., Tallman, C., & Tanner,

B. (2018). Virtual Reality Cue Refusal Video Game for

Alcohol and Cigarette Recovery Support: Summative

Study. JMIR Serious Games, 6(2), e7.

Piper, M. E., Baker, T. B., Benowitz, N. L., Smith, S. S., &

Jorenby, D. E. (2020). E-Cigarette dependence

measures in dual users: Reliability and relations with

dependence criteria and e-cigarette cessation. Nicotine

and Tobacco Research, 22(5), 756–763.

Traboulsi, H., Cherian, M., Abou Rjeili, M., Preteroti, M.,

Bourbeau, J., Smith, B. M., Eidelman, D. H., &

Baglole, C. J. (2020). Inhalation toxicology of vaping

products and implications for pulmonary health.

International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(10),

3495.

Usoh, M., Catena, E., Arman, S., & Slater, M. (2000). Using

presence questionnaires in reality. Presence:

Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 9(5), 497–503.

Vogel, E. A., Prochaska, J. J., & Rubinstein, M. L. (2020).

Measuring e-cigarette addiction among adolescents.

Tobacco Control, 29(3), 258–262.

Weser, V. U., & Hieftje, K. D. (2020). Invite Only VR: A

Vaping Prevention Game: An Evidence-Based VR

Game for Health and Behavior Change. Special Interest

Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive

Techniques Conference Talks, 1–2.

Witmer, B. G., & Singer, M. J. (1998). Measuring presence

in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire.

Presence, 7(3), 225–240.

Preliminary Usability Evaluation of a Virtual Reality (VR) Application for Quitting Nicotine Vaping

889