Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of

EEG Signals Among Sexes

Shujauddin Syed

a

, Sifat Redwan Wahid

b

, Ted Pedersen

c

, Jack Quigley

d

and Arshia Khan

e

Department of Computer Science, University of Minnesota Duluth, 1114 Kirby Drive, Duluth, MN, U.S.A.

Keywords: Project-Based Learning, Protocol Design, Pedagogy, Cognitive Performance, Signal Processing,

ElectroenCephalogram.

Abstract: This paper focuses on the development of a structured protocol to support undergraduate students in conduct-

ing in-class projects. Project-Based Learning (PBL) has gained recognition as an effective educational ap-

proach, offering students practical, hands-on experience and fostering a deeper understanding of the applica-

tion of theoretical concepts. Despite its advantages, undergraduate students often face challenges in success-

fully completing in-class projects due to the lack of well-defined protocols to guide their efforts. To address

this gap, we, a team of graduate students serving as teaching assistants (TAs), designed this protocol based

on their close interaction with undergraduates and an understanding of the challenges they face. This protocol

aims to enhance the ability of undergraduate students to complete their project in a systematic and structured

way. To demonstrate the implementation, we provide a step-by-step guide based on an in-class project

conducted as part of the “Sensors and IoT” course (CS4432/5432) at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

1 INTRODUCTION

PBL is an educational approach where students en-

gage in an extended learning process by investigat-

ing and solving real-world problems or challenges

(Brundiers and Wiek, 2013; Krajcik, 2006). PBL is

one of the modern technologies that universities in

many parts of the world are adopting to develop en-

gineering graduates capable of being the practical ap-

plication oriented engineers needed in industry. This

pedagogical approach is well established and has

been reviewed extensively (Bell, 2010; Helle et al.,

2006; Thomas, 2010).

In PBL, students collaborate in teams over an ex-

tended period, applying critical thinking, problem-

solving, and research skills to produce tangible out-

comes or products.

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1162-1849

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8327-1698

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0417-4123

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0550-6848

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8779-9617

2 PROBLEM/ SOLUTION

DESCRIPTION

Our research was motivated by the critical need to de-

velop a comprehensive, adaptable methodology for

undergraduate research that addresses the persistent

challenges in experiential learning. Traditional ed-

ucational approaches have increasingly struggled to

prepare students for the complex, interdisciplinary

de-mands of modern professional environments. By

uti-lizing neurological assessment techniques, we

aimed to create a robust protocol that not only

facilitates effective project-based learning but also

pro- vides insights into cognitive engagement across

different tasks and potential sex-based cognitive

variations.

Teaching assistants (TAs) work closely with un-

dergraduates and maintain a deep understanding of

the specific challenges they face while working on

projects. This close involvement allows TAs to de-

velop solutions that effectively address these needs.

898

Syed, S., Wahid, S. R., Pedersen, T., Quigley, J. and Khan, A.

Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of EEG Signals Among Sexes.

DOI: 10.5220/0013369100003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 898-905

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Therefore, the protocol we have developed is de-

signed to be highly effective for undergraduate stu-

dents.

2.1 Neurological Foundations

The human brain’s remarkable plasticity allows for

diverse cognitive responses across different neural re-

gions. Our study specifically focused on four key

brain wave channels that correspond to distinct cog-

nitive states:

• Alpha Waves: Associated with relaxation and

mental coordination, primarily observed in the

oc-cipital and parietal regions

• Beta Waves: Linked to active thinking,

problem-solving, and focused mental activity,

predomi-nantly observed in the frontal and

temporal lobes

• Theta Waves: Connected to creativity,

emotional processing, and memory formation,

primarily ac-tive in the limbic system

• Delta Waves: Characteristic of deep sleep and

unconscious processing, typically associated

with the default mode network

2.1.1 Sex-Based Neurological Variations

Emerging research has increasingly highlighted po-

tential differences in neural signal activity between

males and females. A seminal study by Ingalhalikar et

al. (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013) demonstrated signifi-cant

structural and functional connectivity differences in

male and female brains. Specifically, their research

revealed that male brains tend to show more intra-

hemispheric connectivity, while female brains exhibit

greater inter-hemispheric connectivity, suggesting nu-

anced differences in cognitive processing.

3 PROJECT HYPOTHESIS

We hypothesized that females might demonstrate

heightened neural responses in certain cognitive tasks,

particularly those involving:

• Complex social cognition

• Multi-tasking scenarios

• Emotional intelligence-related activities

• Fine motor skill coordination

This hypothesis builds upon previous research by

Cahill (Cahill, 2006), which suggested that hormonal

and structural differences can lead to varied cog-nitive

processing strategies between males and fe-males.

However, we approached this hypothesis with

methodological rigor, acknowledging the potential for

individual variability and the dangers of overgeneral-

ization.

In the context of the current academic and pro-

fessional landscape, traditional teaching methods of-

ten fall short in equipping students with the practi-cal

skills and hands-on experience that are required in the

current job market or graduate school. PBL has

emerged as an effective pedagogical approach to

bridge this gap, offering students valuable opportuni-

ties for experiential learning.

While graduate students commonly participate in

projects, undergraduate students often face

difficulties due to limited time, resource constraints,

unclear ex-pectations, and inadequate support.

Further, under-graduate students often lack the

experience required to effectively collaborate in

teams, leading to chal-lenges in communication,

coordination, and delega-tion of tasks. To address

these limitations, we de-signed a simplified yet

effective protocol for under-graduate students that

can help them in producing a successful project.

To address these limitations we design a

simplified yet effective protocol for undergraduate

students that can help them in producing a successful

project.

4 RELATED WORKS

Philip et al. (Sanger and Ziyatdinova, 2014) outlined

three common approaches for integrating projects

into Project-Based Learning (PBL) curricula. These

include:

• Demonstration-Type Competitive Projects:

These projects are designed primarily for

pedagogical purposes and are not typically

industry-based. Their objective is to teach and

practice project-related skills through

competitive yet instructional activities.

• Focused Single-Discipline Projects: These are

embedded within specific courses and

concentrate on a particular academic discipline.

• Multidisciplinary Capstone Projects: These are

typically senior-year projects that involve

tackling complex, open-ended problems, often

in collabo-ration with industry.

Zhang et al. (Zhang and Ma, 2023) conducted a

meta-analysis of 66 studies spanning two decades,

demonstrating that project-based learning signifi-

cantly enhances students’ academic performance, af-

fective attitudes, and critical thinking skills when

compared to traditional teaching methods.

Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of EEG Signals Among Sexes

899

Vogler et al. (Vogler et al., 2018) conducted a

two-year qualitative study examining the learning

pro-cesses and outcomes of an interdisciplinary

project-based learning (PjBL) task involving

undergraduate students from three courses. The

findings highlighted the development of soft skills

(e.g., communication, collaboration) and hard skills

(e.g., programming, de-sign, market research) while

emphasizing the impor-tance of course design

improvements to fully achieve interdisciplinary

objectives.

Cujba et al. (Cujba and Pifarre,´ 2024) per-formed

a quasi-experimental study involving 174 sec-ondary

students to examine the impact of innovative,

technology-enhanced, collaborative, and data-driven

project-based learning on attitudes toward statistics.

The experimental group showed reduced anxiety, in-

creased affect, and more positive attitudes toward us-

ing technology for learning statistics, while the con-

trol group exhibited no positive changes. The findings

highlight the potential of this instructional approach

to improve both statistical problem-solving skills and

students’ attitudes, emphasizing its educational sig-

nificance.

Wurdinger et al. (Wurdinger and Rudolph, 2009)

conducted a study at a student-centered charter school

in Minnesota to explore definitions of success and the

teaching of life skills by surveying 147 alumni,

students, teachers, and parents. The results showed

that life skills such as creativity (94%) and the abil-

ity to find information (92%) were highly valued,

while academic skills like test taking (33%) and note

taking (39%) ranked lower. Despite this, 50% of

alumni graduated from college, above the national av-

erage. The study suggests that project-based learning

schools should integrate academic skill development

to better prepare students for college.

Rehman et al. (Rehman, 2023) highlight that PBL

enhances critical thinking, engagement, and practical

skills in computer science and engineering but faces

barriers like faculty resistance, resource constraints,

and assessment challenges. They propose addressing

these issues with training, resources, and evaluation

improvements.

5 METHODOLOGY

This study adopts a mixed-methods exploratory re-

search design within the Project-Based Learning

(PBL) paradigm, integrating both procedural inno-

vation and empirical investigation. We propose a

comprehensive protocol that goes beyond traditional

project management approaches by emphasizing sys-

tematic rigor, methodological transparency, and scal-

able educational intervention strategies.

5.1 Protocol Architecture

1. Preparatory Phase: Conceptualization and Design

Problem Identification:

• Critical survey of research domain: Comprehen-

sive examination of existing literature, identifying

key theories, methodological approaches, and cur-

rent research gaps in neurocognitive performance

assessment.

• Identification of knowledge gaps:

Systematically analyzing unexplored intersections

between cog-nitive task performance, neural signal

variations, and interdisciplinary research

methodologies.

• Articulating precise research questions: Devel-

oping focused, measurable inquiries that address

specific cognitive engagement and neural signal

correlations across diverse experimental tasks.

• Comprehensive literature review: Conducting

an exhaustive review of peer-reviewed sources, syn-

thesizing theoretical frameworks, and establishing a

robust conceptual foundation for the study.

Methodological Calibration:

• Systematic research design assessment: Critically

evaluating potential research methodologies, en-suring

alignment with research objectives and maximizing

scientific rigor and reproducibility.

• Instrument selection and validation:

Meticulously selecting measurement tools and

validation pro-tocols to ensure precise, reliable data

collection across multiple cognitive engagement

scenarios.

• Preliminary feasibility analysis: Conducting a

comprehensive assessment of resource require-

ments, technological capabilities, and potential

methodological constraints.

• Epistemological alignment verification:

Ensuring theoretical consistency and methodological

coher-ence across experimental design, data

collection, and analytical frameworks.

2. Operational Framework Sampling Methodology:

• Purposive, stratified sampling approach: Imple-

menting a carefully designed sampling strategy that

ensures representative participant selection based on

predefined cognitive and demographic criteria.

• Demographic representativeness: Ensuring par-

ticipant diversity and balanced representation across

gender, age, and potential cognitive vari-ation

parameters.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

900

• Minimization of selection bias: Developing

rigor-ous recruitment protocols that mitigate potential

systemic biases in participant selection and data

interpretation.

5.2 Sensor Setup Design

Our approach utilizes advanced sensor fusion tech-

niques, strategically integrating multiple physiologi-

cal measurement modalities to enhance data compre-

hensiveness and interpretative depth. The BIOPAC

MP36 multi-modal sensor suite provided sophis-

ticated capabilities for high-resolution Electroen-

cephalographic (EEG) signal acquisition. Figure 2

represents the BIOPAC MP36 that we used for data

acquisition.

Figure 1: BIOPAC MP36 Data Acquisition Unit.

Figure 2: Eilik Robot for Sensor Fusion.

Analytical Strategy

• Paired t-test statistical inference: Employing

comparative statistical techniques to assess sig-

nificant differences in neural signal characteristics

across experimental conditions.

• 95% confidence interval framework: Establish-

ing robust statistical confidence boundaries to val-

idate research findings and minimize Type I error

probability.

• Degrees of freedom: Implementing a three-

parameter model specifically calibrated to the four-

channel EEG signal acquisition system, en-suring

precise statistical modeling.

Dimensional Analysis Approach

Our analysis diverge from traditional univariate

approaches by:

• Examining multiple neuro-physiological dimen-

sions: Simultaneously investigating intercon-nected

neural signal characteristics to provide comprehensive

cognitive performance insights.

• Investigating variations in signals from different

individuals: Analyzing inter-individual neural re-

sponse variability to understand cognitive pro-

cessing heterogeneity.

• Mapping neural activity across specialized brain

regions: Developing detailed neural activation maps

to correlate specific cognitive tasks with lo-calized

brain function.

• Correlating task-specific cognitive engagement:

Establishing nuanced relationships between ex-

perimental tasks and corresponding neural signal

patterns.

5.3 Experimental Parameters

Sample Characteristics:

The research cohort consisted of four carefully se-

lected individuals, ensuring a controlled and focused

study. The group maintained a balanced gender repre-

sentation, with two male and two female participants,

to mitigate potential biases arising from gender-based

cognitive variations.

Experimental Tasks:

• Strategic cognitive engagement (chess): Assess-

ing complex decision-making processes, strate-gic

planning, and cognitive resource allocation through

chess-based challenges.

• Interactive robotic interface interaction with

Eilik: Exploring human-machine interaction

dynamics and adaptive cognitive responses in

technological engagement scenarios.

• Physical motor performance tasks, pushups,

squats: Investigating neural signal variations dur-ing

structured physical exertion and motor skill

execution.

• Memory and cognitive processing challenges:

Evaluating working memory capacity, informa-tion

processing speed, and cognitive flexibility by making

participants play a memory game.

• Fine motor skill coordination assessment:

Ex-amining precise neuromuscular control, and

cognitive-motor integration by balancing a pencil.

This methodology is a conceptual blueprint for

optimizing educational research practices, by closing

the gap between theoretical understanding and practi-

cal implementation.

Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of EEG Signals Among Sexes

901

Figure 3: Sample image from our data collection sessions.

6 PRACTICAL

CONSIDERATIONS AND

METHODOLOGICAL

CHALLENGES

Project Implementation Strategies.

6.1 Simplified Project Setup

The simplest way to establish an in-class project in-

volves:

• Defining clear, measurable learning objectives:

Articulating specific, quantifiable goals that align

with course learning outcomes and provide a con-

crete framework for student research engagement.

• Selecting a focused, achievable research

question: Identifying a narrow, manageable research

inquiry that balances academic rigor with practical

con-straints of in-class project limitations.

• Establishing minimal viable technological

infras-tructure: Selecting cost-effective, accessible

tech-nological tools that support research objectives

without overwhelming student resources.

• Creating a flexible yet structured project time-

line: Developing a comprehensive project sched-ule

that allows for iterative progress while main-taining

clear milestone achievements.

• Providing clear guidelines for collaborative

work: Establishing transparent expectations,

communi-cation protocols, and collaborative

framework to maximize team productivity and

individual ac-countability.

6.2 Dealing with Small Sample Sizes

Handling small sample sizes requires careful strate-

gies to ensure reliable and meaningful results. One

approach is to use statistical techniques like boot-

strapping, which involves creating multiple simulated

datasets from the original data to estimate patterns

and variability. Another method is to focus on clear

and transparent reporting, explicitly outlining the lim-

itations of the study so that conclusions are inter-

preted with caution. Small studies can also be framed

as exploratory, aiming to generate ideas or

hypotheses for future research. Finally, researchers

can minimize bias by carefully designing the study,

controlling for key variables like age, gender, or other

relevant fac-tors to reduce noise in the results.

6.3 Navigating Inconclusive Research

Outcomes

Handling inconclusive results in academic projects

re-quires:

• Recognizing negative results as scientifically

valuable: Repositioning inconclusive findings as

critical contributions to methodological under-

standing and future research design.

• Documenting methodological insights:

Compre-hensively cataloging research challenges,

limita-tions, and unexpected outcomes to enhance

future investigative approaches.

• Articulating limitations transparently: Providing

detailed, honest assessments of research constraints to

maintain academic credibility and re-search integrity.

• Proposing future research directions:

Developing constructive recommendations for

subsequent in-vestigations based on current study’s

limitations and insights.

• Maintaining academic integrity in reporting:

En-suring honest, comprehensive reporting of re-

search outcomes regardless of initial hypothetical

expectations.

6.4 Data Collection Without Formal

IRB

Ethical strategies for preliminary human-subject data

collection:

• Obtaining verbal or written informed consent:

Developing comprehensive participant informa-tion

protocols that prioritize individual autonomy and

voluntary participation.

• Anonymizing participant data: Implementing

ro-bust data anonymization techniques to protect in-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

902

dividual privacy and research participant confi-

dentiality.

• Minimizing potential participant risks:

Conducting thorough risk assessments and

implementing protective measures to prevent

physical or psychological harm.

• Limiting data collection to non-invasive

methods: Restricting research methodologies to

minimally intrusive data collection techniques that

prioritize participant well-being.

• Providing clear opt-out mechanisms:

Establishing transparent participant withdrawal

protocols that respect individual autonomy

throughout the research process.

• Maintaining strict confidentiality protocols:

Developing comprehensive data management

strategies that protect participant privacy and adhere

to ethical research standards.

6.5 Rapid Data Analysis Techniques

Efficient data processing involves utilizing pre-

configured data analysis scripts, using automated

cleaning protocols, and using machine learning pre-

processing techniques to streamline workflows and

improve accuracy. Modular frameworks enhance

flexibility and scalability, while advanced visualiza-

tion techniques enable rapid pattern recognition and

intuitive analysis. Together, these strategies ensure

re-liable, adaptable, and efficient data handling.

6.6 Neurological Task-Region

Correlation Rationale

Our activity selection for specific brain regions was

predicated on:

• Established neuroscientific literature: Grounding

experimental design in comprehensive review of peer-

reviewed neurological research and established

cognitive mapping methodologies.

• Neuroplasticity and cognitive engagement

principles: Incorporating contemporary understanding

of brain adaptability and task-specific neural net-work

activation.

• Maximizing signal-to-noise ratio in neural

recordings: Strategically selecting experimental tasks

to optimize neural signal clarity and minimize po-

tential measurement artifacts.

• Targeting regions with known functional

specialization: Focusing on brain regions with well-

documented correlations to specific cognitive pro-

cesses and performance metrics.

By integrating these practical considerations, we

enhance the methodological robustness and pedagog-

ical value of our research approach, transforming po-

tential challenges into opportunities for methodologi-

cal innovation.

7 RESULTS AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

7.1 EEG Signal Analysis Methodology

Our protocol for analyzing EEG signals involved a

comprehensive multi-channel approach using the

Biopac MP36 sensor system. We focused on four

distinct brain wave channels (Channels 40-43) cor-

responding to different neural activity states: Al-pha

(relaxation), Beta (active thinking), Delta (deep

sleep/unconscious), and Theta (creativity/emotional

processing) waves.

7.2 Data Analysis Mechanism

To ensure robust statistical analysis, we employed a

systematic data processing methodology:

• Recorded EEG signals across five distinct

cognitive and physical tasks: chess, interaction with

Eilik robot, physical exercise, memory games, and

pencil balancing.

• Calculated average frequency values for each

wave channel separately for male and female

participants.

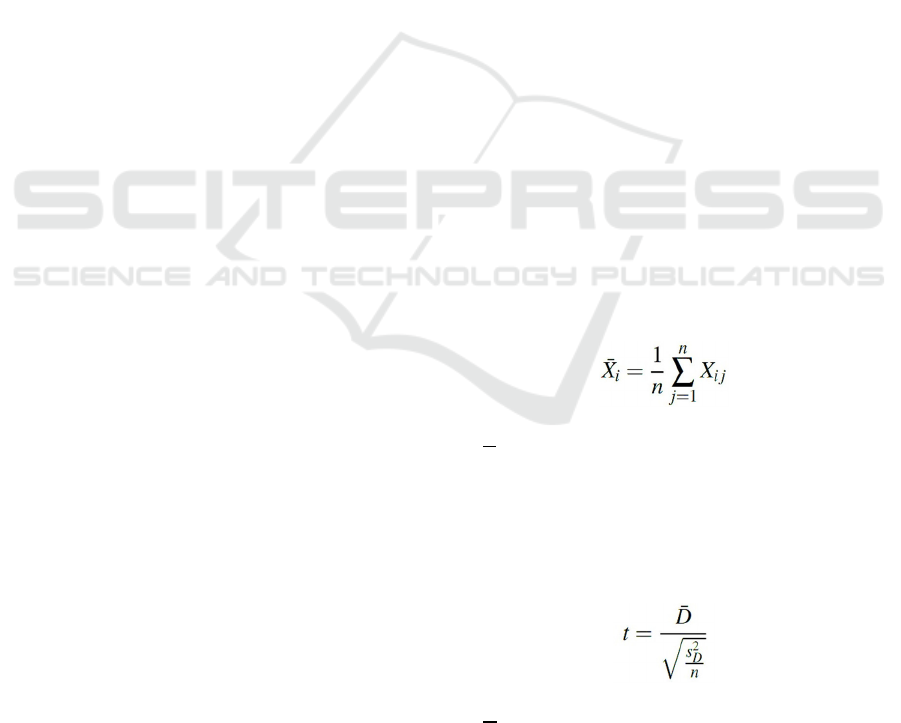

(1)

Where:

–𝑋

represents the mean frequency for channel 𝑖

–𝑛 is the number of measurements

–𝑋

represents the j-th measurement in channel 𝑖

• Utilized a paired t-test at a 95% confidence

interval with three degrees of freedom to validate

potential gender-based neurological differences.

(2)

Where:

–𝐷

is the mean difference between paired observations

–𝑠

is the standard deviation of the differences

– 𝑛 is the sample size

Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of EEG Signals Among Sexes

903

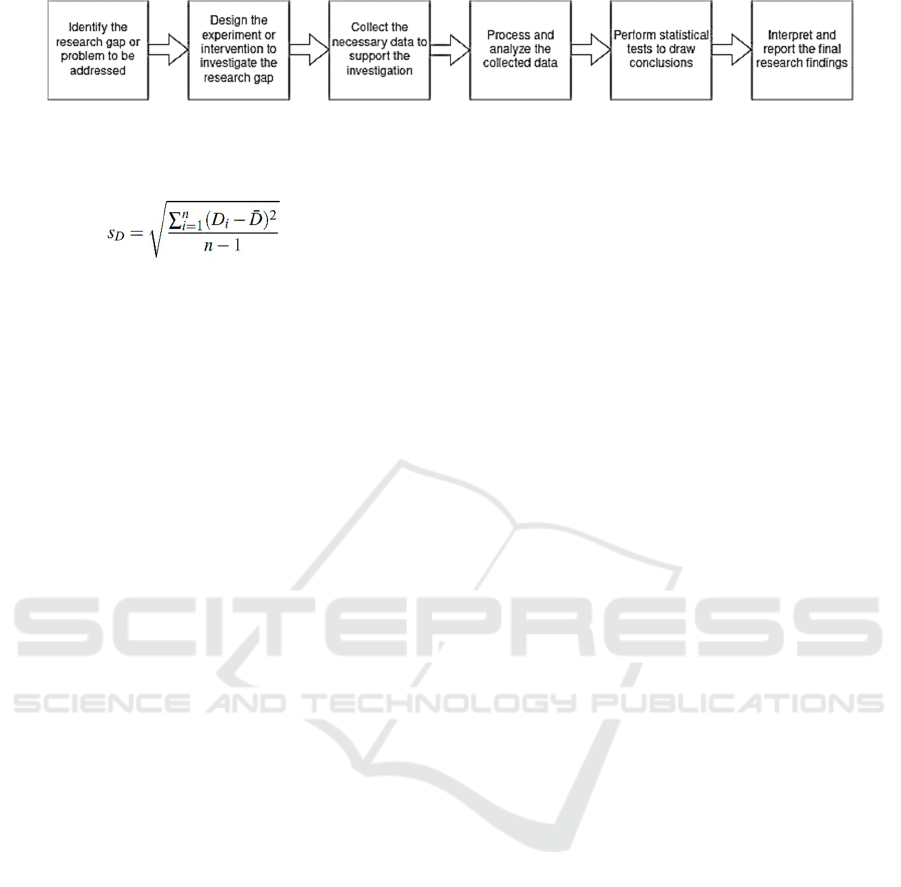

Figure 4: Our designed protocol for in-class projects of undergraduate students.

The paired t-test formula expanded:

(3)

7.3 Statistical Interpretation

Critically, our paired t-test results demonstrated that

the observed variations did not constitute statistically

significant differences. This finding is mathematically

represented by:

|𝑡

| 𝑡

(4)

Where:

• 𝑡

represents the computed t-statistic

from our experimental data.

• 𝑡

represents the threshold value at the

95% confidence interval.

• Degrees of freedom (n = four channels):

𝑑𝑓 𝑛 1 3

Significance criteria:

𝑝 0.05

This suggests that while individual task

performances exhibited unique neurological

signatures, aggregate brain wave patterns remained

remarkably consistent across genders, with no

statistically significant neurological differentiation

detected.

7.4 Ethical Component

Throughout the research, we maintained stringent

ethical standards. We obtained formal consent from

the participants before conducting the experiments.

We ensured inclusivity and equal treatment of all

participants. We were attentive to minimizing

participant discomfort and remained sensitive to

gender-related considerations.

8 DISCUSSION

In this study, we have determined that the best way to

start and finish an in-class project within a span of a

short time is to implement a structured, yet flexible

project-based learning (PBL) approach that balances

systematic rigor with adaptive methodological

strategies.

8.1 Key Findings and Insights

Our research yielded several critical insights into

undergraduate project management and cognitive

performance assessment:

The proposed protocol shows significant potential

for standardizing undergraduate research method-

ologies across disciplinary contexts.

Sensor fusion techniques provide a nuanced ap-

proach to understanding cognitive performance,

revealing subtle variations in neural signal pat-terns

that traditional methods might overlook.

8.2 Limitations and Future Research

Directions

While our study provides valuable insights, several

limitations warrant acknowledgment. The number of

small sample size (4 participants) really limits the

generalizability of the experiment. Increasing the

sample size and including participants from a diverse

age group can improve the effectiveness of the

results. But as our experiment was limited to the

classroom and we did not have IRB training to

experiment with human subjects we could not include

more training samples. Expanding this experiment

outside of the classroom can be a future-work for this

experiment. Furthermore, our experiments focused

on a specific set of cognitive tasks. Including a

diverse set of cog-nitive tasks can capture the brain

parts better.

9 CONCLUSION

Our research represents a significant step towards

developing a more systematic, technologically inte-

grated approach to undergraduate project-based

learn-ing. By combining rigorous methodological

frame-works with innovative technological tools, we

demon-strate the potential to transform traditional

educa-tional practices.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

904

The proposed protocol is not just a procedural

guideline but a conceptual blueprint for optimizing

educational research practices. It bridges the critical

gap between theoretical understanding and practical

implementation, offering a scalable model for inter-

disciplinary project management.

REFERENCES

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century:

Skills for the future. The clearing house, 83(2):39–43.

Brundiers, K. and Wiek, A. (2013). Do we teach what we

preach? an international comparison of problem-and

project-based learning courses in sustainability.

Sustainability, 5(4):1725–1746.

Cahill, L. (2006). Why sex matters for neuroscience. Nature

Reviews Neuroscience, 7(6):477–484.

Cujba, A. and Pifarre,´ M. (2024). Enhancing stu-dents’ at-

titudes towards statistics through innovative technol-

ogy-enhanced, collaborative, and data-driven project-

based learning. Humanities and Social Sci-ences Com-

munications, 11(1):1–14.

Helle, L., Tynjal¨a,¨ P., and Olkinuora, E. (2006). Project-

based learning in post-secondary education–theory,

practice and rubber sling shots. Higher education,

51:287–314.

Ingalhalikar, M., Smith, A., Parker, D., Satterthwaite, T. D.,

Elliott, M. A., Ruparel, K., Hakonarson, H., Gur, R. E.,

Gur, R. C., and Verma, R. (2013). Sex dif-ferences in

the structural connectome of the human brain. Proceed-

ings of the National Academy of Sci-ences,

111(2):823–828.

Krajcik, J. (2006). Project-based learning. Rehman, S. U.

(2023). Trends and challenges of project-based learning

in computer science and engineering education. In Pro-

ceedings of the 15th International Conference on Edu-

cation Technology and Computers, pages 397–403.

Sanger, P. A. and Ziyatdinova, J. (2014). Project based

learning: Real world experiential projects creating the

21st century engineer. In 2014 International Con-fer-

ence on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL),

pages 541–544.

Thomas, J. W. (2010). A review of research on project-

based learning. 2000. The Autodesk Foundation: San

Rafael.

Vogler, J. S., Thompson, P., Davis, D. W., Mayfield, B. E.,

Finley, P. M., and Yasseri, D. (2018). The hard work of

soft skills: augmenting the project-based learning ex-

perience with interdisciplinary teamwork. Instr. Sci.,

46(3):457–488.

Wurdinger, S. and Rudolph, J. (2009). A different type of

success: Teaching important life skills through project

based learning. Improving Schools, 12(2):115–129.

Zhang, L. and Ma, Y. (2023). A study of the impact of pro-

ject-based learning on student learning effects: A meta-

analysis study. Frontiers in psychology, 14:1202728.

Protocol Design for in-Class Projects: Comparative Analysis of EEG Signals Among Sexes

905