Stratum Corneum Light Confinement: Monte Carlo Verification

Leah DeVos

1

, Gennadi Saiko

2a

and Alexandre Douplik

2,3 b

1

Department of Engineering, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

2

Department of Physics, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada

3

iBest, Keenan Research Centre of the LKS Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Canada

Keywords: Refractive Index, Turbid Tissues, Light Propagation.

Abstract: Significance: The epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin, plays a crucial role in protecting the body from

UV radiation, chemical substances, and physical trauma. Its top layer, the stratum corneum (SC), consists of

dead skin cells with low water content (~20%), creating a refractive index gradient between the SC and

underlying tissue. This gradient traps light within the SC layer, but its impact on light propagation in tissues

remains largely unexplored. Aim: The study investigates how refractive index variations in the skin influence

light propagation in tissues. Approach: Monte Carlo (MC) light transport simulations were performed in

media with and without refractive index mismatches. Results: Light confinement in the SC increases the

fluence rate by 12-35% compared to underlying tissue, particularly when the underlying tissue has low diffuse

reflectance. This effect is most pronounced when the SC thickness exceeds the reduced scattering length

(~150-600 μm for visible light). Such thicknesses occur in glabrous skin (palms, soles) and thickened areas

like calluses and corns. Conclusions: By comparing MC simulations, we attribute this light confinement to

the SC's high refractive index due to its low water content. This stratum corneum light confinement (SCLC)

phenomenon may lead to an inaccurate estimation of light distribution, resulting in errors in some skin

diagnostic parameters measured via diffuse reflection, such as water and total hemoglobin content, and blood

oxygenation.

1 INTRODUCTION

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, and

it plays a crucial role in protecting the body from

external insults such as UV radiation, chemical

substances, and physical trauma. The epidermis can

be subdivided into two sublayers: non-living and

living epidermis. The non-living epidermis (~20 μm

thick) consists of only dead squamous cells, which are

highly keratinized with a high lipid (~20%) and

protein (60%) content and a relatively low (~20%)

water content (Bashkatov, 2011). In terms of water

content, the stratum corneum radically differs from

the underlying skin layers, which have much higher

water content—the typical water content in these live

skin layers is 70%.

Due to the significant difference in refractive

index between proteins/lipids and water, skin tissues

can be stratified into two layers: stratum corneum

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5697-7609

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9948-9472

with the higher refractive index (n = 1.467) and all

other underlying tissue with lower refractive index

(n = 1.383).

The low water content of stratum corneum has

significant implications on water content imaging

(Saiko, 2023a), particularly for thickened areas (corns

and calluses). While the light propagation in

multilayer skin models has been studied analytically

(Sergeeva, 2024; Phillips, 2009; Liemert, 2017),

numerically (Chang, 2023; Sadeghi, 2022;

Yudovsky, 2011; Grossweiner, 1992, Dehghani,

2003), and experimentally (Farrell, 2001), the effect

of refractive index gradient on skin optics has not

been adequately explored so far, which may have

certain implications for actively developing optical

medical devices and consumer health fields. In a

recent development, Saiko (Saiko, 2023b) developed

an analytical approach to account for the refractive

index gradient and predicted the light confinement in

the stratum corneum.

DeVos, L., Saiko, G. and Douplik, A.

Stratum Corneum Light Confinement: Monte Carlo Verification.

DOI: 10.5220/0013369700003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 397-402

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

397

The current work aims to elucidate the impact of

a significant gradient of water content and,

consequently, the gradient of the refractive index of

the skin layers in tissues, which can help more

accurately describe the light propagation in tissues. In

this study, we validate the model predictions (Saiko,

2023b) with established Monte Carlo simulations of

light propagation (specifically the gpumcml program

(Alerstamet, 2010)).

2 METHODS

2.1 Tissue Model

We have performed Monte Carlo simulations of light

transport in a two-layer model (the stratum corneum

and underlying tissue) to elucidate the peculiarities of

light propagation in the proposed model.

2.1.1 Index of Refraction

The refractive indexes of tissue structure elements,

such as the fibrils, the interstitial medium, nuclei,

cytoplasm, organelles, and the tissue itself, can be

derived using the law of Gladstone and Dale, which

states that the resulting value represents an average of

the refractive indices of the components related to

their volume fractions. Water content varies in

different skin layers. To account for the impact of

water content on the refraction index, a simple

approach was proposed by (Troy, 2001), which

assumes that the tissue consists of protein and water.

If proteins have a refractive index of 1.5, we get the

following expression, which is a generalized version

of (Troy, 2001), which used water content, c

w

=0.7,

𝑛

=

(

1−𝑐

)

1.5 + 𝑐

𝑛

(1)

Water's refractive index in the spectrum's visible

range (380 - 700 nm) can be estimated as 1.333 (Hale,

1973). However, its wavelength-dependent

approximations can be used to account for the

dependence on the light wavelength if necessary. Due

to the significant difference in refractive index

between proteins and water, tissues can be stratified

into two layers: stratum corneum with a higher

refractive index and all other underlying tissue with a

lower refractive index. They will be denoted by

subindexes 1 and 2, respectively. Subindex 0 will

correspond to the surrounding medium (air). Note

that while stratum corneum has a high lipid content,

it does not change our assumptions, as lipids also

have a high refractive index. We have calculated the

refractive index for tissue layers using Eq.1. We

considered two scenarios: c

w

=0.7 (n=1.383) and c

w

=0.2 (n=1.467).

2.1.2 Underlying Tissue Optical Parameters

As we are interested primarily in the effect of

refractive index gradient, we have selected three sets

of underlying tissue parameters to emulate the low,

medium, and high reflectance R (approximately 0.1,

0.3, and 0.5, respectively). The (μ

a

, μ

s

) values were

set to (17cm

-1

, 80cm

-1

), (9cm

-1

, 180cm

-1

), and (5cm

1

,

275cm

-1

), respectively. The anisotropy factor, g, was

set to 0.7.

2.1.3 Stratum Corneum Layer Thickness

We selected seven stratum corneum (SC) layer

thickness values to emulate a broad range of

physiological conditions: d= 20, 50, 100, 200, 500,

1000, and 2000μm.

2.1.4 Stratum Corneum Optical Parameters

We have selected one scenario for the absorption

coefficient in stratum corneum: μ

a

= 5cm

1

, which

corresponds approximately to flesh absorption at

400nm. We selected three values for the reduced

coefficient of scattering: 60, 30, and 15 cm

-1

. To

emulate the effect of different wavelengths (their

relative size compared with the scatterer size), we

have considered three values for scattering

anisotropy: g = 0, 0.4, and 0.8. Thus, we generated

three values of (μ

s

, g) for each respective μ'

s

. As we

expect that the observed phenomena will depend on

the SC layer thickness in comparison with the

scattering transport length and reduced scattering

transport length, we selected parameters d, μs, and g

to cover all possible relationships between SC layer

thickness and the scattering transport length and

reduced scattering transport length.

2.2 Monte Carlo Simulations

Using the GPU MCML Monte Carlo software

(Alerstamet, 2010), we simulated light propagation in

a two-layer model to validate the results of the

analytical prediction. The primary model is the semi-

infinite tissue (d

2

=6mm, n

2

=1.383) covered with the

stratum corneum layer (n

1

=1.467) with thicknesses

described in the 2.1.3 section. In total, 3x3x3x7=189

scenarios were simulated.

To elucidate the impact of the refractive index

gradient, we have also simulated a scenario without a

water content gradient (matched SC/underlying tissue

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

398

boundary). Namely, we set n

1

=n

2

=1.383 (matched

SC/underlying tissue boundary) for the same value of

the SC absorption coefficient (μ

a

= 5cm

-

1). In total,

3x3x3x7=189 scenarios were simulated and were

used as a baseline.

Overall, we simulated 2x3x3x3x7=378 scenarios.

From the Monte Carlo simulations, we obtained

diffuse reflectance R

d

and the dependence of flux

intensity on the depth Φ(z). We used 10

8

photons for

each simulation. Resolutions in vertical and lateral

directions were set to 10μm and 100μm, respectively.

3 RESULTS

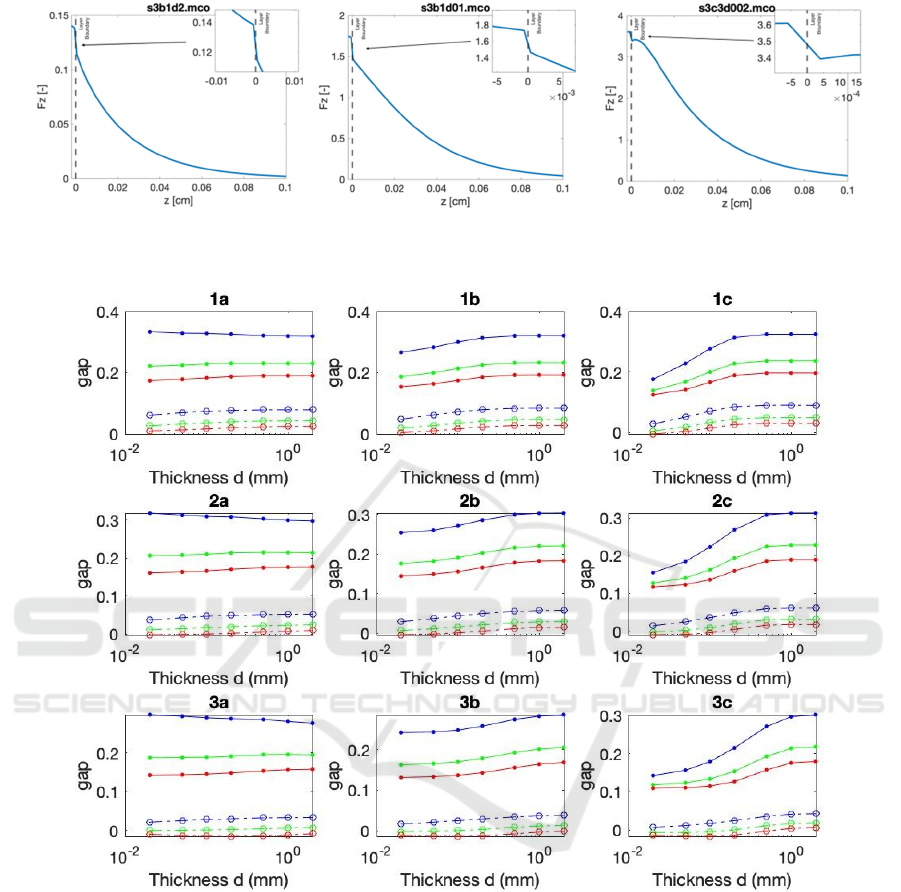

We have calculated the fluence rate around the

SC/underlying tissue interface (20μm above and

1mm in the underlying tissue). Examples of the light

distributions are depicted in Fig. 1.

To characterize the fluence rate behavior at the

interface and below the interface in the underlying

tissue, we have calculated the jump in the light

intensity over the SC/underlying tissue interface and

the slope of the fluence rate in the underlying tissue

just below the interface (termed as "gap"). The gap

was defined as,

𝑔𝑎𝑝 = (𝐼

−𝐼

)/𝐼

(2)

Here, I

+

and I

-

are light flux just above (I

+

) and

just below (I-) the SC/underlying tissue interface.

In Fig. 2, one can see the dependence of the gap

on the SC thickness for all (μs', g) scenarios for

matched (dashed lines) and mismatched (solid lines)

boundaries for μ

a

=5cm

-1

. Panels are arranged with

increasing g (horizontally) and μ

s

' (vertically).

As predicted by the analytical model, mismatched

boundaries demonstrate a very significant effect on

the gap. From Fig. 2, one can see that the gap is

approximately 5x larger in the case of the mismatched

boundary where n

1

= 1.467 for the stratum corneum

and n

2

= 1.383 for the underlying tissue (see, for

example, panel 3c, where for R=0.1, the gap is on the

scale 0.02 vs. 0.15 for 20μm thickness).

One can see that the gap dependences on R and g

are quite significant. As expected, lower reflectance

of the underlying tissue, R, translates into more

significant gaps. Also, for realistic anisotropy factors

(g is around 0.7 in biological tissues), the gap

increases with an increase in g. Conversely, the gap

decreases as μ

s

' increases.

4 DISCUSSIONS

Our analysis shows we can expect several noticeable

effects caused by the mismatched boundary between

the stratum corneum and underlying tissues.

In particular, it is known that the light intensity is

amplified under the surface, which can be described

by the ratio of under-the-surface light intensity to the

external light intensity. In the case of a matched

boundary, the ratio will be close to 1+R (forward and

backward fluxes). However, the ratio typically has

higher values (amplification) than predicted by 1+R

for mismatched boundaries. In the proposed two-

layer model, we have an additional amplification. The

light intensity in the SC layer is noticeably higher

than just below the interface with underlying tissues,

as demonstrated by Fig. 1 and 2. This phenomenon

can be attributed to several factors. The first factor is

the higher value of the refractive index of the stratum

corneum. It increases the overall light intensity under

the air/SC interface. However, the light intensity in

the stratum corneum layer is noticeably (10-30%)

higher than in the underlying tissue layer (see Fig. 2).

We have conducted the baseline MC calculations to

investigate this phenomenon for the matched

boundary between SC and underlying tissues. In this

case, the change (gap) is significantly smaller (see

Fig. 2). Thus, we can attribute the effect primarily to

the mismatched boundary between SC and the

underlying tissue and refer to it as the confinement of

light in the stratum corneum layer.

The light confinement in the SC layer is similar

to fiber optics. Total internal reflections of the light

on the interfaces with air and underlying tissues cause

it. In particular, the critical angles on these interfaces

are φ

c,a=

arcsin(1/n

10

) and φ

c,ut

=arcsin(1/n

12

),

respectively. The core differences with fiber optics

are that a) instead of highly transparent media (fiber

optics), we have a highly scattering media, b) instead

of a 1D case (light propagation along an axis in the

optical fiber), we have a 2D case (light propagation in

the x-y plane), and c) critical angles on both surfaces

are not identical. However, a broad range of similar

phenomena should likely be observed. For example,

it should result in a broadening of the point spread

function (PSF), which is caused by the fact that the

SC acts as a light guide in the x-y plane. Also,

similarly to light leakage due to fiber bending, the

same phenomena can be expected to be observed on

curved surfaces like heel skin.

As one can see from Fig. 2, the confinement effect

is more noticeable for low values of the diffuse

reflectance R. It does make sense, as in this case, the

underlying tissue is a less significant source of

Stratum Corneum Light Confinement: Monte Carlo Verification

399

Figure 1: Examples of the fluence rate depth dependence at the SC/underlying tissue interface. (a) with a stratum corneum

thickness of 2000 μm, (b) 100 μm, and (c) 20 μm.

Figure 2: Dependence of the gap on SC thickness d in all (μ

s

', g) scenarios for no mismatch (dashed lines) vs. mismatch (solid

lines) boundary conditions for various underlying tissue reflectance R. R = 0.1 (blue lines), 0.3 (green lines). 0.5 (red lines).

Panels are arranged with increasing g (horizontally) and μ

s

' (vertically).

recycled photons for the stratum corneum layer. Thus,

most recycled photons come from the total internal

reflection on the interfaces between stratum

corneum/air and stratum corneum/underlying tissues.

For high diffuse reflectance, the underlying tissue is

the primary source of recycled photons compared

with relatively weak total internal reflectance on the

stratum corneum/underlying tissues interface. Thus,

the confinement effects (e.g., the additional

amplification) are masked by stronger mechanisms

(photon injection from the underlying tissues).

Also, the effect depends significantly on the

thickness of the stratum corneum layer. In particular,

for small (compared with the distance between

consecutive scatterings) thicknesses, the photons that

enter the stratum corneum from the air pass through

the SC layer without experiencing total internal

reflection. The same applies to the significant part of

photons entering the SC layer from the underlying

tissues. As there is no total internal reflection for

photons entering from the underlying tissue, all

photons from the underlying tissue (other than a

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

400

minute fraction of specularly reflected ones) will

enter the SC layer; however, just photons with an

angle of incidence φ>arcsin(1/n

2

) will experience

total internal reflection on the SC/air interface (the

critical angle is 46.3° for n

2

=1.383). All others escape

the SC through the SC/air interface immediately.

However, even a small fraction of photons that

experienced total internal reflection on the air/SC

interface will immediately exit the SC layer on the

SC/underlying tissue interface. Thus, the light

confinement will be minimal. In this case, photons

within the tissue almost do not feel the presence of the

SC layer.

As the SC layer thickness increases, the entering

photons start experiencing scattering events. In this

case, the light becomes homogenized across various

directions in the SC layer. If the thickness is larger

than the reduced scattering length, the photon that

enters the SC layer from any direction will be

homogenized in the SC layer. Thus, the share of

oblique photons, which experience total internal

reflection in the SC layer, will increase. As a result,

the confinement will increase to its maximum value,

as confirmed by Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 2).

As the reduced scattering coefficient for the SC is

on the scale 15-70 cm

-1

in the visible range of the

spectrum1, the light confinement phenomenon is

maximal in stratum corneum layers with a thickness

of at least 150μm and 600μm in blue and red ranges

of the spectrum, respectively. These values are typical

for the glabrous skin of palms and soles and thickened

epidermis like calluses and corns. These estimations

were confirmed by Monte Carlo simulations (Fig. 2).

However, the effect is almost absent for isotropic

(Rayleigh) scattering, which can be strong for shorter

wavelengths (<500nm).

The predicted phenomena (the stratum corneum

light confinement or SCLC) may have implications

for applications in biospectroscopy and bioimaging.

There are several possible mechanisms. Firstly, it

may impact the sampling/interrogating depth. For

example, one can see that for the small diffuse

reflectance, the contribution of the SC may dominate

in the total reflectance, which may skew certain

measurements. Secondly, it may impact the point

spread function, which, in turn, may impact the

dependence of the reflected light as a function of

source-detector distance in spatially resolved

spectroscopy. For example, current consumer-grade

tissue oxygenation sensors (like Oura ring) can often

be interchangeably deployed on non-glabrous and

glabrous skin, characterized by a much thicker

stratum corneum layer. These phenomena will be

explored in future work, where we plan to use Monte

Carlo simulations of light propagation in tissues to

identify other possible effects of light confinement in

stratum corneum on measurements of water and total

hemoglobin content and blood oxygenation.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Monte Carlo simulations confirmed light

confinement in the stratum corneum layer. The light

in the stratum corneum is confined between two

interfaces: air and underlying tissues. The effect can

be attributed to the high refractive index of the

stratum corneum caused by low water content,

compared with underlying tissues and scattering in

the stratum corneum layer. Light confinement in the

stratum corneum is maximal in cases where the

thickness of the stratum corneum layer is more than

the reduced scattering length. In the visible range of

the spectrum, the light confinement phenomenon is

maximal in stratum corneum layers with a thickness

of at least 150μm (the blue range) and 600 m (the red

range). In addition, the relative effect of light

confinement increases with the decrease of the

underlying tissue reflectance. If unaccounted for, the

stratum corneum light confinement (SCLC)

phenomenon may potentially lead to an inaccurate

estimation of the light distribution, resulting in errors

in some skin diagnostic parameters measured via the

diffuse reflection, such as water and total hemoglobin

content and blood oxygenation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge funding from NSERC

Alliance (A.D), NSERC Personal Discovery an I2I

(A.D. and G. S.), NSERC RTI (A.D.), Toronto

Metropolitan University Health Fund (A.D.), and

Toronto Metropolitan University Faculty of Science

Discovery Accelerator program (G.S.).

REFERENCES

Alerstamet, E. al., (2010) Next-generation acceleration and

code optimization for light transport in turbid media

using GPUs, Biomed. Opt. Express 1, 658-675.

Bashkatov, A.N., Genina, E.A., Tuchin, V.V., (2011)

Optical Properties of Skin, Subcutaneous, and Muscle

Tissues: a Review, J. Inn. Opt. Health Sci, 4(1) 9-38.

Chang, Y., & Gao, W. (2023). Mueller matrix model of

polarized light propagation in layered human skin in

Stratum Corneum Light Confinement: Monte Carlo Verification

401

backscattering configuration. Journal of Applied

Physics, 134(22). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0171926

Dehghani, H., Brooksby, B., Vishwanath, K., Pogue, B.W.,

and Paulsen, K.D., (2003) The effects of internal

refractive index variation in nearinfrared optical

tomography: a finite element modelling approach,

Physics in Medicine & Biology, 48(16): 2713.

Farrell, T.J. and Patterson, M.S., (2001) Experimental

verification of the effect of refractive index mismatch

on the light fluence in a turbid medium, J Biomed Opt,

6(4): 468-473.

Grossweiner, LI, Karagiannes, JL, Jones, LR, Johnson, PW.

(1992) Reflection and transmission coefficients in

plane-parallel layers with refractive-index mismatch,

Applied optics.; 31(1):106-109.

Hale, G. M., Querry, M. R. (1973) Optical constants of

water in the 200 nm to 200 µm wavelength region,

Appl. Opt., 12, 555-563.

Liemert, A., Reitzle, D. and Kienle, A., (2017) Analytical

solutions of the radiative transport equation for turbid

and fluorescent layered media, Scie Rep, 7(1): 3819.

Phillips, K.G. and Jacques, S.L., (2009) Solution of

transport equations in layered media with refractive

index mismatch using the P Nmethod, JOSA A, 26(10):

2147-2162.

Sadeghi, B., Siahpoush, V., & Nikniazi, A. (2022). A basic

estimation on the light distribution and thermal

behavior of the human skin through transfer matrix

method coupled with Pennes’ bio-heat equation. Waves

in Random and Complex Media, 32(4), 1803–1819.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2020.1838666

Saiko, G. (2023) Feasibility of Skin Water Content Imaging

Using CMOS Sensors, Sensors, 23, 919.

Saiko, G. (2023) Light confinement in stratum corneum,

arXiv:2309.13146.

Sergeeva, E., Kurakina, D., Turchin, I., & Kirillin, M.

(2024). A refined analytical model for reconstruction

problems in diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Journal of

Innovative Optical Health Sciences, 17(05), 2342002.

https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793545823420026

Troy, T. L., Thennadil, S. N., (2001) Optical properties of

human skin in the near-infrared wavelength range of

1000 to 2200 nm, J. Biomed. Opt. 6, 167-176

Yudovsky, D. and Durkin, A.J., (2011) Hybrid diffusion

and two-flux approximation for multilayered tissue

light propagation modeling, Applied optics, 50(21):

4237-4245.

BIOIMAGING 2025 - 12th International Conference on Bioimaging

402