Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two

Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits

Zilu Liang

1,2 a

1

Ubiquitous and Personal Computing Lab, Kyoto University of Advanced Science (KUAS), Kyoto, Japan

2

Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

Protein Intake, Protein Deficiency, Dietary Assessment, Urine Test, Personalized Nutrition, Metabolomics.

Abstract:

This study aimed to compare two consumer-grade mail-in nutrition test kits, Flemi Check and VitaNote, in

measuring protein intake and identifying protein deficiencies. A total of 18 subjects (10 male, 8 female) aged

19 to 36 years participated. Descriptive statistics revealed that most subjects consumed between 60 and 80

grams of protein per day, slightly below the recommended 80 grams. The Flemi Check test identified 15 sub-

jects as protein-deficient, while the VitaNote test identified 11. A significant disparity in protein consumption

measurements was found, with the Flemi Check consistently underestimating protein consumption compared

to the VitaNote test for 16 out of the 18 subjects, with a mean difference of 17.11 grams. However, both kits

showed good agreement in estimating the recommended daily protein intake, with only a 2-gram difference.

Given the high precision of the VitaNote test, the Flemi Check may not be considered as a reliable tool for

assessing protein intake.

1 INTRODUCTION

Protein is a crucial macro-nutrient for building and

maintaining a healthy body for people across all

ages (Antonio et al., 2024; Groenendijk et al., 2019;

Wu, 2016; Paddon-Jones et al., 2015). Protein is es-

sential not only for structural components of the body,

such as muscles, bones, blood, and skin, but also

for regulating body functions, including the produc-

tion of hormones and immune function (Wu, 2016).

Studies have shown that higher protein intake can

help treat or prevent a range of diseases (Wu, 2016;

Layman, 2009; Layman et al., 2008; Madeira et al.,

2021). Conversely, protein deficiency can lead to

many health problems, including sarcopenia in the el-

derly, which is a rick factor for fractures, disability,

and frailty (Groenendijk et al., 2019; Granic et al.,

2018; Wilkinson et al., 2018; Paddon-Jones et al.,

2015).

Despite its importance, many people fail to meet

the recommended daily protein intake. Approximate

70% of people across all age groups do not reach

their protein targets, which vary based on gender, age,

and physical activity levels (Traylor et al., 2018; Wu,

2016; Bauer et al., 2013; Elango et al., 2010). Surveys

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2328-5016

indicate that many people are unsure about whether

they are consuming enough protein or feel that their

intake is insufficient.

Recently, consumer-oriented nutrition testing

kits, particularly those for protein consumption, have

emerged on the market. These services typically

involve collecting a urine sample at home and

mailing it back to the company for analysis, where

urinary metabolites are assessed using proprietary

algorithms. Nutritional studies have shown that ana-

lyzing urinary metabolites is an effective method for

monitoring dietary intake (Rafiq et al., 2021; Posma

et al., 2020; Garcia-Perez et al., 2017) and offers

potential for personalized nutrition (Ulusoy-Gezer

and Rakıcıo

˘

glu, 2024; Cuparencu et al., 2024; Bren-

nan and de Roos, 2023; Adams et al., 2020). Urine

samples provide insights into recent dietary intake,

reflecting consumption from a few hours to several

days (Rafiq et al., 2021). While challenges remain

in developing biomarkers for food intake (Beck-

mann et al., 2020), urine analysis offers several

benefits, including improve objectivity (Ottaviani

et al., 2024), scalability, and affordability com-

pared to blood tests (Ulusoy-Gezer and Rakıcıo

˘

glu,

2024; Garcia-Perez et al., 2017; Bokhof et al., 2010).

This method also provide a non-invasive and practical

906

Liang, Z.

Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits.

DOI: 10.5220/0013372600003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 906-913

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

means for individuals to monitor their nutri-

tion (Adams et al., 2020; Liang and Martell, 2015).

These consumer kits promise an easy and acces-

sible way for individuals to track their protein intake

without the need for clinical visits or expensive med-

ical testing. However, it remains unclear how reliable

the results are across different services. This study

aims to investigate the agreement between two pop-

ular protein consumption testing kits: Flemi Check

and VitaNote. Specifically, the study has two primary

objectives. First, we seek to assess the degree of con-

cordance between the two test kits. Given the impor-

tance of accuracy and precision in consumer tests, un-

derstanding their consistency is critical for users trust.

Second, this pilot study aims to estimate the average

daily protein consumption of young adults, a group

often underrepresented in protein intake research. To

the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to

directly compare these two kits and provide data on

protein consumption levels in young adults through

consumer-oriented testing services.

2 METHOD

2.1 Experiment Protocol

Subjects were recruited through the distribution of

flyers around the campus of Kyoto University of Ad-

vanced Science (KUAS). To be eligible, subjects had

to be adults, capable of understanding explanations in

English, and able to attend an in-persona briefing in

the lab. Exclusion criteria included individuals who

had been diagnosed with chronic kidney diseases or

those who weighed over 200 kg, as this exceeds the

measurement range of the body composition analyzer

used in the study. This study was approved by the

ethics review board at KUAS.

The experiment began with a one-on-one briefing

session in the lab. During the briefing, subjects were

first provided with an explanation of the study objec-

tives, data management protocols, and were asked to

sign an informed consent form. Subjects were also

instructed on how to collect and mail their urine sam-

ples. In addition, they completed the questionnaire

attached to each test kit as required by the consumer

services.

At the end of the meeting, we measured the body

composition of the subjects using a Tanita RD-800

body composition analyzer. This device employs

dual-frequency technology for accurate body com-

position measurements with a precision of 50 gram.

By utilizing an 8-electrode grip method, the analyzer

measures body fat percentage, muscle mass, and mus-

cle score for the entire body as well as for five indi-

vidual regions: left arm, right arm, left leg, right leg,

and torso.

2.2 Test Kits

Two consumer-grade mail-in nutrition test kits were

compared in this study. Both test kits analyze uri-

nary metabolites and assess them using proprietary

algorithms. Each kit includes a urine collection con-

tainer, one or two test tubes, a return envelope, and

documents outlining the testing procedures as well as

instructions for obtaining informed consent. These

testing services aim to assist users in making dietary

improvements that align with their nutritional needs.

For certain population, such as women and the el-

derly, who may face challenges in meeting their nu-

tritional requirement through food alone, these ser-

vices can be particularly beneficial. Establishing a

consistent and manageable habit of protein intake is

expected to help mitigate various health issues asso-

ciated with protein deficiency, including frailty (Wu,

2016; Layman, 2009; Layman et al., 2008; Madeira

et al., 2021).

Subjects collected urine samples using the pro-

vided container and test tubes at home, securely close

the lid, and place it in the accompanying plastic bag.

To return the sample to the testing center, subjects

simply placed the urine container in the return enve-

lope and mail it back to the companies. Details of the

two test kits are provided below.

2.2.1 VitaNote

The VitaNote mail-in test kit provides a comprehen-

sive analysis of nutrient imbalances through urine

samples, allowing users to assess the status of 19 key

biomarkers. This includes 17 essential nutrients, such

as proteins, vitamins (e.g., Vitamin D, B1, B2, Niacin,

and B6), and minerals (e.g., sodium, potassium, and

calcium), as well as two health markers: oxidative

stress (rust index) and cytokines (conditioning indi-

cator). The kit offers a detailed evaluation of nutrient

deficiencies or excesses, with accompanying advice

based on results to guide dietary adjustments.

Results are presented on a radar chart in the Vi-

taNote app, allowing users to easily visualize nutri-

ent imbalances. Tapping on each element of the chart

provides more detailed information about that specific

nutrient. A proprietary evaluation index is calculated

based on the intake levels of each nutrient. The Vi-

taNote app also includes educational content on the

role of each nutrient, the risks associated with defi-

ciencies or excesses, and food recommendations for

correcting deficiencies.

Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits

907

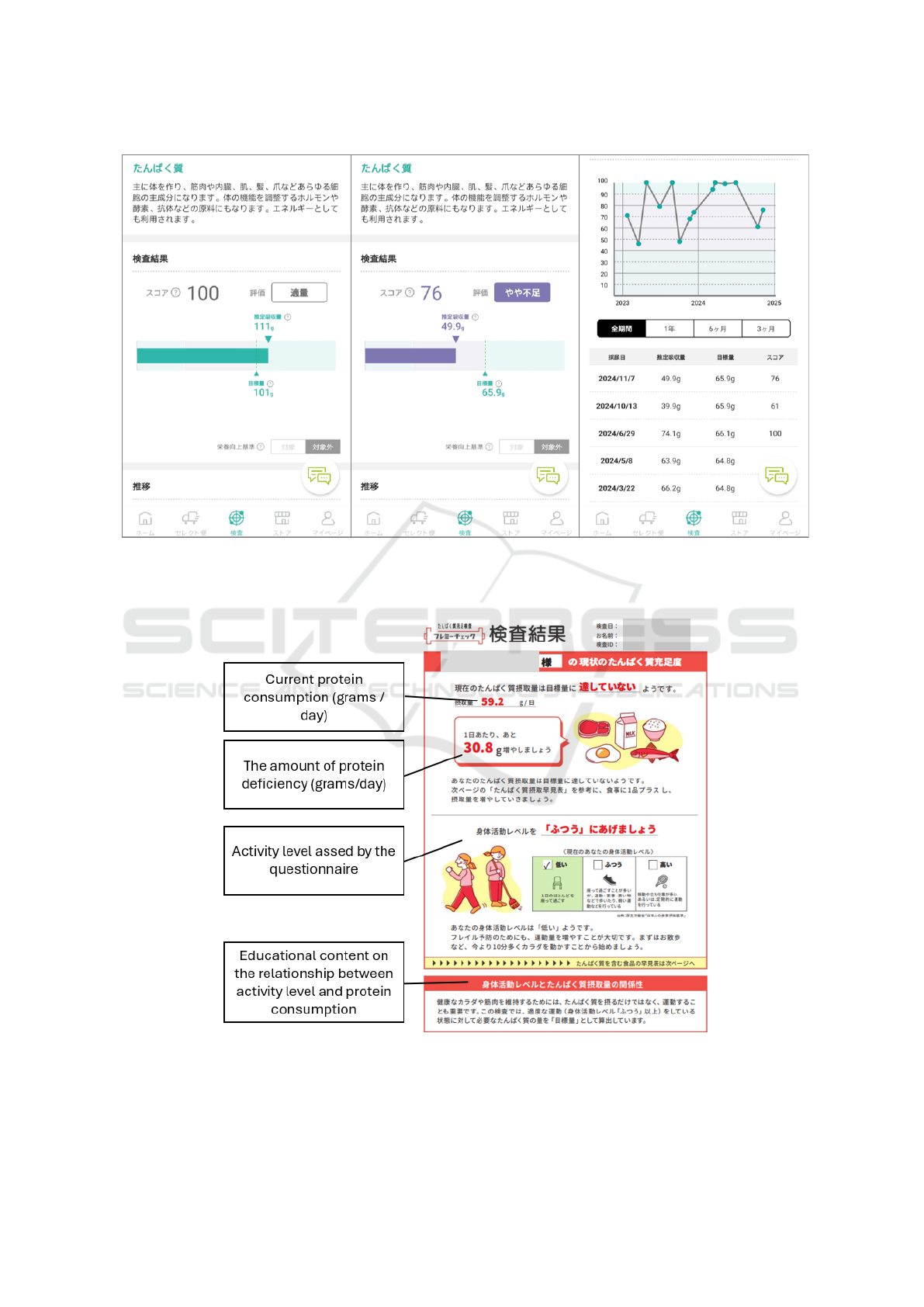

Figure 1: Screenshots of the VitaNote app: Left – an example of sufficient protein intake (111 g versus the recommended

101 g); Middle – an example of insufficient protein intake (49.9 g versus the recommended 65.9 g); Right – a time series plot

showing a user’s protein intake over time.

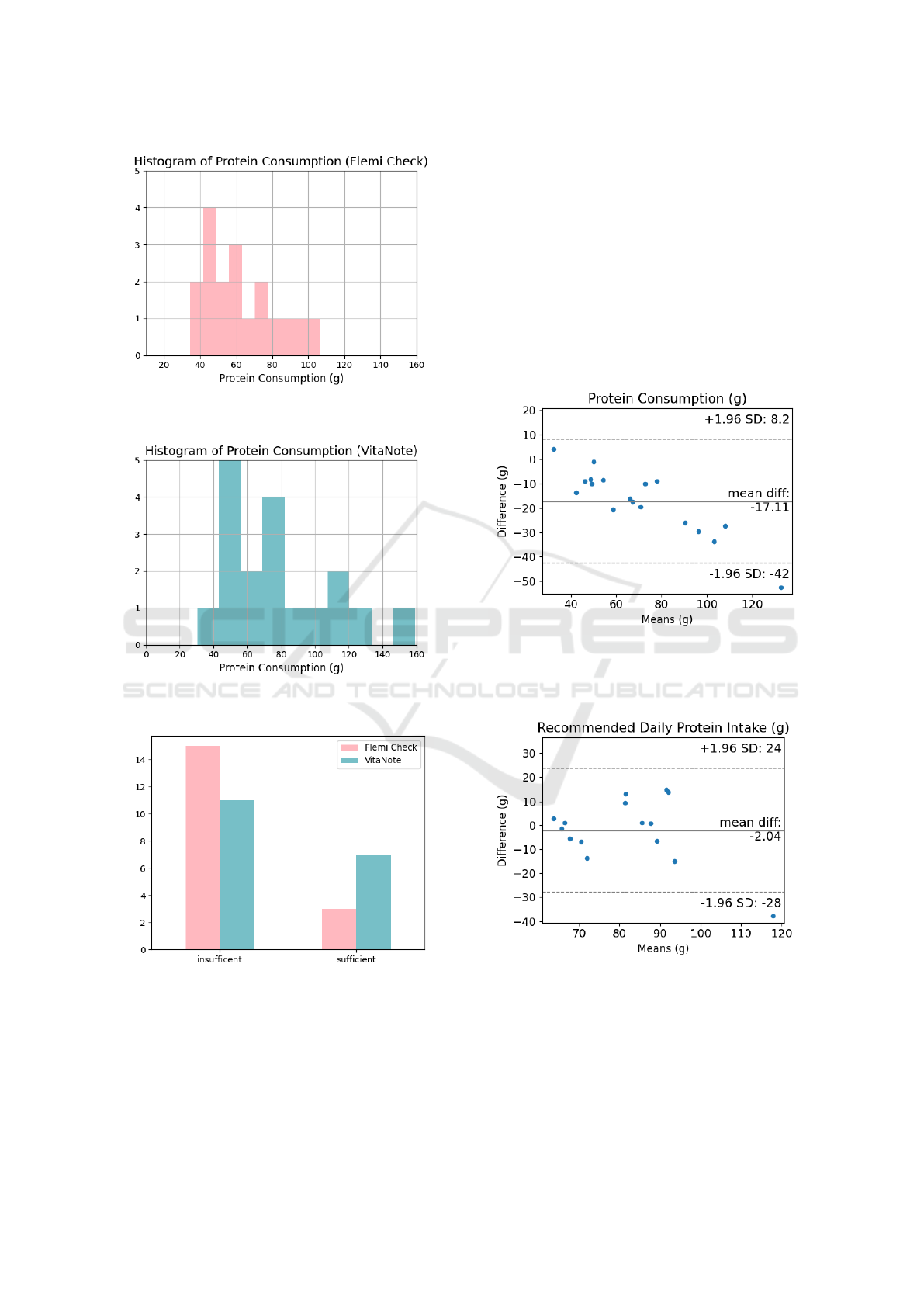

Figure 2: An example of a Flemi Check report showing the current protein consumption, the amount of deficiency, activity

level assessed by the questionnaire, and educational content on the relationship between activity level and protein consump-

tion.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

908

For the purpose of this study, we focus solely

on the measurement of dietary protein consumption.

Some screenshots of the protein measurement results

from the VitaNote app are shown in Figure 1. Accord-

ing to the official website, the precision for measuring

dietary protein consumption is 0.9% (Yukashikado

Inc., 2024). Given the common adopted criteria of 5%

allowable error margin (Maduemem and Rodriguez,

2019; Panteghini et al., 2017), the VitaNote test is

considered to have good accuracy.

2.2.2 Flemi Check

Similar to the VitaNote test, the Flemi Check mail-

in test kit measures dietary protein intake through a

urine sample. It provides insights into current pro-

tein consumption, guidance on how much additional

protein is needed to meet target levels, alongside ad-

vice on activity levels and educational content about

the importance of protein and its sources. However,

the Flemi Check only measures protein and does not

assess other nutrients.

An example of a Flemi Check report is shown in

Figure 2. The report outlines the protein intake mea-

sured from the sample. If intake is insufficient, the re-

port specifies how many additional grams of protein

are needed to reach the target. For individuals with

adequate intake, the report recommends maintaining

their current consumption. The recommended daily

protein intake is calculated by combining measured

intake and any deficiencies. However, for users who

are classified as having sufficient intake, the report

does not include information on the recommended

daily intake.

2.3 Data Analysis

Histograms were created to visualize protein con-

sumption as measured by the two test kits. This al-

lowed for a visual inspection of the distribution of

protein intake for each kit. Bar charts were used to

show the number of subjects categorized as having

sufficient or insufficient protein intake according to

each test kit.

Bland-Altman plots (Bland and Altman, 1986)

were created to assess the level of agreement between

the two test kits. The mean difference and 95% lim-

its of agreement (1.96 ± SD of difference) are also

shown. In clinical settings, if the differences within

the mean equal ± 1.96 standard deviation are not clin-

ically important, then the two test kits are equivalent

and can be used interchangeably (Higgins and Straub,

2006).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

In total 18 subjects (10 male, 8 female) were recruited

for the study. The demographic information and de-

scriptive statistics of protein consumption are sum-

marized in Table 1. The age range of subjects was

between 19 and 36 years at the time of data collec-

tion. Body weight ranged from 51 to 138.5 kg, and

BMI values spanned from 18.1 to 41.8 kg/m

2

. The

majority of subjects reported a medium level of daily

physical activity, while two rated their activity level

as high and one as low. Fourteen subjects engaged

in regular exercise, including activities such as yoga,

cycling, weight training, running, and higher intensity

interval training (HIIT). All subjects followed an om-

nivorous diet, with none adhering to a vegetarian or

vegan diet. Seven subjects were particularly mindful

of their daily protein intake, and four of these were

using protein power supplements. The average rec-

ommended daily protein intake was approximately 80

grams, while actual protein consumption ranged from

60 to 80 grams. On average, subjects were consum-

ing 10 to 20 grams less protein than the recommended

intake.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics.

Metric Average Range

Age (years) 26 [19, 36]

Body weight (kg) 73.41 [51, 138.5]

Muscle mass (kg) 52.8 [40.75, 81.15]

Fat ratio (%) 19.92 [6, 38.3]

Bone mass (kg) 3.04 [2.5, 4.5]

BMI (kg/m

2

) 25.07 [18.1, 41.8]

Protein consumption

by Flemi Check (g)

61.78 [34.4, 106.4]

Protein deficiency by

Flemi Check (g)

19.24 [0, 52.7]

Recommended Intake

by Flemi Check (g)

80.73 [65, 99]

Protein consumption

by VitaNote (g)

78.89 [30.3, 159]

Protein deficiency by

VitaNote (g)

12.33 [0, 48.5]

Recommended Intake

by VitaNote (g)

82.59 [62.3, 136.7]

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the distribution of pro-

tein consumption as measured by the two test kits.

Both distributions are skewed to the left, but the Vi-

taNote test has a longer tail on the right, indicating

a wider range of values, with an outlier at the far

right end. Both distributions peak between 40 and 60

Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits

909

Figure 3: Histogram of protein consumption as measured

by the Flemi Check test kit.

Figure 4: Histogram of protein consumption as measured

by the VitaNote test kit.

Figure 5: Number of subjects identified as protein-sufficient

and protein-insufficient by each test kit.

grams of protein. Correspondingly, 15 subjects were

identified as protein-deficient by the Flemi Check test,

while only 11 subjects were identified as deficient by

the VitaNote test, as shown in Figure 5.

3.2 Agreement between Two Test Kits

As shown in Figure 6, there is a significant disparity

between the two test kits in terms of measured pro-

tein consumption, with a mean difference of 17.11

grams. The Flemi Check kit underestimated protein

consumption for 16 out of the 18 subjects. In addi-

tion, the disparity tended to increase as protein con-

sumption levels rose. On the other hand, the two kits

agreed reasonably well in terms of the recommended

daily protein intake, with a mean difference of only 2

grams, as shown in Figure 7. No significant trend was

observed.

Figure 6: Bland-Altman plot for consumed amount of pro-

tein. The solid line show mean difference, and the dotted

lines show 95% limits of agreement (1.96 ±) SD of differ-

ence.

Figure 7: Bland-Altman plot for recommended amount of

protein. The solid line show mean difference, and the dotted

lines show 95% limits of agreement (1.96 ±) SD of differ-

ence.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

910

4 DISCUSSION

Consumer-grade metabolomics test services represent

an emerging field in personalized nutrition. As nu-

tritional research transition from population-based to

personalized approaches, and from controlled labora-

tory settings to free-living environments, it is impor-

tant to evaluate the validity of these testing methods

and their impact on consumers. However, there are

few studies investigating the validity of urine analy-

sis for measuring protein intake (Bokhof et al., 2010).

This study is the first comparative analysis of two

popular consumer mail-in test kits–the Flemi Check

and the VitaNote–for measuring protein intake and

identifying protein deficiencies. Below we discuss the

implications of the findings in this study.

Firstly, this study revealed that the overall protein

intake of the subjects was slightly below the recom-

mended daily intake of 80 grams, with an average

consumption of 60 to 80 grams per day. According to

the VitaNote results, approximately 60% of the sub-

jects were not consuming sufficient protein. This find-

ing aligns with other nutrition studies that show many

individuals fail to meet recommended protein intake

levels (Traylor et al., 2018; Wu, 2016; Bauer et al.,

2013; Elango et al., 2010). Interestingly, the Flemi

Check test identified a larger proportion of subjects

as protein-insufficient compared to the VitaNote test.

Specifically, 15 subjects were classified as deficient

by the Flemi Check test, while only 11 were iden-

tified as deficient by the VitaNote. This discrepancy

suggests that the Flemi Check may be more conserva-

tive in detecting insufficiency or may have a different

threshold for what constitutes a deficiency.

When comparing the two test kits using the Bland-

Altman plot, a significant disparity emerged in terms

of measured protein consumption. The Flemi Check

test consistently underestimated protein consumption

compared to the VitaNote test for 16 out of the 18

subjects, with a mean difference of 17.11 grams. This

raises concerns about the accuracy of the Flemi Check

in capturing actual protein intake. One possible expla-

nation for the lower readings from the Flemi Check

kit could be differences in the analysis method used to

measure protein. Furthermore, at higher consumption

levels, the Flemi Check showed a more pronounced

underestimation.

In contrast to the significant differences observed

in protein consumption measurements, the two kits

showed a much closer agreement when assessing the

recommended daily protein intake. The mean differ-

ence in recommended intake was only 2 grams, in-

dicating that both kits provide similar estimates for

the ideal protein requirements of the subjects. This

consistency suggests that both tools may be using a

similar formula for assessing general protein needs.

Indeed, there are widely accepted methods for esti-

mating protein requirements, which typically suggest

1.2-1.5 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight

per day (Wu, 2016; Deutz et al., 2014; Elango et al.,

2010), adjusted for factors such as activity level, gen-

der, and age group (Weiler et al., 2023; Vieux et al.,

2022; Wu, 2016; Paddon-Jones et al., 2015). No sig-

nificant trend was observed in this regard, supporting

the notion that the two tests are equally effective for

determining the nutritional targets rather than actual

consumption. However, it is worth noting that while

previous study emphasize the importance of factoring

in the type and quality of protein consumed (Vieux

et al., 2022; Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2012), it remains

unclear whether and how such factors are considered

in the analysis of these test kits.

several limitations should be considered. First,

the test results were not compared to a gold standard

method for measuring protein intake (e.g., validated

dietary recalls (Yuan et al., 2017) or 24-hour urinary

nitrogen analysis (Bingham, 2003)). Without such a

reference, it is challenging to assess the absolute ac-

curacy of either kit. Second, the sample size of 18

subjects is relatively small, which may limit the gen-

eralizability of our findings. Future studies should

incorporate a medical test as a benchmark for com-

parison and include a larger, more diverse sample to

further validate these results and explore the factors

that may influence the accuracy of each test kit.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, while both the Flemi Check and VitaN-

ote test kits provide valuable information on users’

protein intake needs, they differ in their ability to as-

sess actual protein consumption. The Flemi Check

may tend to underestimate protein intake, particularly

at higher levels of consumption, whereas both kits

show good agreement in estimating recommended

protein intake. Given the high precision of the Vi-

taNote test, the Flemi Check may not be considered

as a reliable tool for assessing protein intake.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the subjects for their

valuable contribution to this study.

Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits

911

REFERENCES

Adams, S. H., Anthony, J. C., Carvajal, R., Chae, L., Khoo,

C. S. H., Latulippe, M. E., Matusheski, N. V., Mc-

Clung, H. L., Rozga, M., Schmid, C. H., Wopereis,

S., and Yan, W. (2020). Perspective: Guiding princi-

ples for the implementation of personalized nutrition

approaches that benefit health and function. Advances

in Nutrition, 11(1):25–34.

Antonio, J., Evans, C., Ferrando, A., Stout, J., Antonio, B.,

Cinteo, H., Harty, P., Arent, S., Candow, D., Forbes,

S., Kerksick, C., Pereira, F., Gonzalez, D., and Krei-

der, R. (2024). Common questions and misconcep-

tions about protein supplementation: what does the

scientific evidence really show? Journal of the Inter-

national Society of Sports Nutrition, 21:2341903.

Bauer, J., Biolo, G., Cederholm, T., Cesari, M., Cruz-

Jentoft, A. J., Morley, J. E., Phillips, S., Sieber, C.,

Stehle, P., Teta, D., Visvanathan, R., Volpi, E., and

Boirie, Y. (2013). Evidence-based recommendations

for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: A

position paper from the prot-age study group. Jour-

nal of the American Medical Directors Association,

14(8):542–559.

Beckmann, M., Wilson, T., Lloyd, A. J., Torres, D. P.,

Goios, A., Willis, N. D., Lyons, L., Phillips, H. C.,

Mathers, J. C., and Draper, J. (2020). Challenges asso-

ciated with the design and deployment of food intake

urine biomarker technology for assessment of habit-

ual diet in free-living individuals and populations—a

perspective. Frontiers in Nutrition, 7.

Bingham, S. A. (2003). Urine nitrogen as a biomarker for

the validation of dietary protein intake. The Journal

of Nutrition, 133(3):921S–924S.

Bland, J. M. and Altman, D. G. (1986). Statistical methods

for assessing agreement between two methods of clin-

ical measurement. The Lancet, 327(8476):307–310.

Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 8476.

Bokhof, B., G

¨

unther, A. L. B., Berg-Beckhoff, G., Kroke,

A., and Buyken, A. E. (2010). Validation of protein

intake assessed from weighed dietary records against

protein estimated from 24 h urine samples in children,

adolescents and young adults participating in the dort-

mund nutritional and longitudinally designed (donald)

study. Public Health Nutrition, 13:826 – 834.

Brennan, L. and de Roos, B. (2023). Role of metabolomics

in the delivery of precision nutrition. Redox Biology,

65:102808.

Cuparencu, C., Bulmus¸-T

¨

uccar, T., Stanstrup, J., la barbera,

G., Roager, H. M., and Dragsted, L. (2024). Towards

nutrition with precision: unlocking biomarkers as di-

etary assessment tools. Nature Metabolism, 6.

Deutz, N. E., Bauer, J. M., Barazzoni, R., Biolo, G., Boirie,

Y., Bosy-Westphal, A., Cederholm, T., Cruz-Jentoft,

A., Krznaric¸, Z., Nair, K. S., Singer, P., Teta, D., Tip-

ton, K., and Calder, P. C. (2014). Protein intake and

exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Rec-

ommendations from the espen expert group. Clinical

Nutrition, 33(6):929–936.

Elango, R., Humayun, M. A., Ball, R. O., and Pencharz,

P. B. (2010). Evidence that protein requirements have

been significantly underestimated. Current Opinion in

Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 13:52–57.

Garcia-Perez, I., Posma, J., Gibson, R., Chambers, E.,

Hansen, T., Vestergaard, H., Hansen, T., Beckmann,

M., Pedersen, O., Elliott, P., Stamler, P., Nicholson,

J., Draper, J., Mathers, P., Holmes, E., and Frost, P.

(2017). Objective assessment of dietary patterns by

use of metabolic phenotyping: a randomised, con-

trolled, crossover trial. The Lancet Diabetes & En-

docrinology, 5.

Granic, A., Mendonc¸a, N., Sayer, A. A., Hill, T. R.,

Davies, K., Adamson, A., Siervo, M., Mathers, J. C.,

and Jagger, C. (2018). Low protein intake, muscle

strength and physical performance in the very old:

The newcastle 85+ study. Clinical Nutrition, 37(6,

Part A):2260–2270.

Groenendijk, I., Boeft, L., van Loon, L., and Groot, L.

(2019). High versus low dietary protein intake and

bone health in older adults: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Computational and Structural Biotech-

nology Journal, 17.

Higgins, P. A. and Straub, A. J. (2006). Understanding the

error of our ways: Mapping the concepts of validity

and reliability. Nursing Outlook, 54(1):23–29.

Layman, D. (2009). Dietary guidelines should reflect new

understandings about adult protein needs. Nutrition &

metabolism, 6:12.

Layman, D., Clifton, P., Gannon, M., Krauss, R., and Nut-

tall, F. (2008). Protein in optimal health: Heart disease

and type 2 diabetes. The American journal of clinical

nutrition, 87:1571S–1575S.

Liang, Z. and Martell, M. A. C. (2015). Framing self-

quantification for individual-level preventive health

care. In International Conference on Health Informat-

ics.

Madeira, T., Severo, M., Oliveira, A., Gorj

˜

ao Clara, J., and

Lopes, C. (2021). The association between dietary

patterns and nutritional status in community-dwelling

older adults-the pen-3s study. European journal of

clinical nutrition, 75.

Maduemem, K. and Rodriguez, Y. (2019). How sensitive

are dipstick urinalysis and microscopy in making di-

agnosis of urinary tract infection in children? Inter-

national journal of preventive medicine, 10:62.

Ottaviani, J. I., Sagi-Kiss, V., Schroeter, H., and Kuhnle,

G. G. (2024). Reliance on self-reports and esti-

mated food composition data in nutrition research in-

troduces significant bias that can only be addressed

with biomarkers. eLife, 13:RP92941.

Paddon-Jones, D., Campbell, W. W., Jacques, P. F.,

Kritchevsky, S. B., Moore, L. L., Rodriguez, N. R.,

and van Loon, L. J. (2015). Protein and healthy ag-

ing234. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition,

101(6):1339S–1345S.

Panteghini, M., Ceriotti, F., Jones, G., Oosterhuis, W., Ple-

bani, M., and Sandberg, S. (2017). Strategies to define

performance specifications in laboratory medicine: 3

years on from the milan strategic conference. Clinical

Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), 55.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

912

Posma, J., Garcia-Perez, I., Frost, G., Aljuraiban, G., Chan,

Q., Horn, L., Daviglus, M., Stamler, J., Holmes,

E., Elliott, P., and Nicholson, J. (2020). Nutri-

ome–metabolome relationships provide insights into

dietary intake and metabolism. Nature Food, 1.

Rafiq, T., Azab, S. M., Teo, K. K., Thabane, L., Anand,

S. S., Morrison, K. M., de Souza, R. J., and Britz-

McKibbin, P. (2021). Nutritional metabolomics and

the classification of dietary biomarker candidates: A

critical review. Advances in Nutrition, 12(6):2333–

2357.

Traylor, D., Gorissen, S., and Phillips, S. (2018). Perspec-

tive: Protein requirements and optimal intakes in ag-

ing: Are we ready to recommend more than the rec-

ommended daily allowance? Advances in Nutrition,

9:nmy003–nmy003.

Ulusoy-Gezer, H. G. and Rakıcıo

˘

glu, N. (2024). The fu-

ture of obesity management through precision nutri-

tion: Putting the individual at the center. Current Nu-

trition Reports, 13:455–477.

Vieux, F., R

´

emond, D., Peyraud, J.-L., and Darmon, N.

(2022). Approximately half of total protein in-

take by adults must be animal-based to meet non-

protein, nutrient-based recommendations, with varia-

tions due to age and sex. The Journal of Nutrition,

152(11):2514–2525.

Weiler, M., Hertzler, S. R., and Dvoretskiy, S. (2023). Is

it time to reconsider the u.s. recommendations for di-

etary protein and amino acid intake? Nutrients, 15(4).

Wilkinson, D., Piasecki, M., and Atherton, P. (2018). The

age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function:

Measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy

and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing Research

Reviews, 47:123–132.

Wu, G. (2016). Dietary protein intake and human health.

Food Funct., 7:1251–1265.

Wu, G., wu, Z., Dai, Z., Yang, Y., Wang, W., Liu, C., Wang,

B., Wang, J., and Yin, Y. (2012). Dietary require-

ments of “nutritionally non-essential amino acids” by

animals and humans. Amino acids, 44.

Yuan, C., Spiegelman, D., Rimm, E. B., Rosner, B. A.,

Stampfer, M. J., Barnett, J. B., Chavarro, J. E., Subar,

A. F., Sampson, L. K., and Willett, W. C. (2017).

Validity of a dietary questionnaire assessed by com-

parison with multiple weighed dietary records or 24-

hour recalls. American Journal of Epidemiology,

185(7):570–584.

Yukashikado Inc. (2024). Mail-in nutrition test kit vitanot.

https://vitanote.jp/service/vitanote. Accessed: 2024-

12-16.

Assessing Dietary Protein Intake: A Comparative Study of Two Consumer Mail-In Nutrition Test Kits

913