Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical

Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the

Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in Germany

Vera Ries

1

, Reinhard Schuster

2,5

, Paul-Ulrich Menz

3

, Klaus-Peter Thiele

1

, Bernhard van Treeck

4

and

Mareike Burmester

2,5

1

Medical Advisory Service Institution of the Statutory Health Insurance in North Rhine (MD Nordrhein), 40212 D

¨

usseldorf,

Germany

2

Medical Advisory Board of Statutory Health Insurance in Northern Germany (MD Nord), 23554 L

¨

ubeck, Germany

3

Medical Advisory Board of Statutory Health Insurance in Westphalia-Lippe (MD Westfalen-Lippe), 48153 M

¨

unster,

Germany

4

Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), 10587 Berlin, Germany

5

Institute of Mathematics, University of L

¨

ubeck, 23562 L

¨

ubeck, Germany

Keywords:

Multidimensional Correlations, Medical Informatics in Quality Assurance, Statistical and Epidemiological

Evaluations, Statutory Health Insurance in Germany, Medical Advisory Board, Mathematica by Wolfram

Research.

Abstract:

In quality assurance within the Medical Advisory Board in Germany, the structures that are primarily organ-

ised by federal state are are being networked nationwide. The aim is to implement a sufficiently standardised

nationwide assessment. The differing regional starting points are simply due to the different mandates from the

health insurance funds. In up to four levels of supra-regional interaction, a standardised assessment is being

steadily improved in the implemented process. This process is being improved on a continuous basis. Statis-

tical and epidemiological evaluations with proven health economic measures and graph-theoretical methods

using the Mathematica software system from Wolfram Research.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the context of social insurance, medical reports

are prepared across all relevant insurance branches.

These include statutory health insurance, statutory

long-term care insurance, statutory pension insur-

ance, statutory accident insurance, statutory occupa-

tional illness insurance and statutory unemployment

insurance. Additionally, they are utilised in the con-

text of private health insurance, cf. (Nedopil, 2014),

(Nolting et al., 2016), (Polak et al., 2018), (Strahl

et al., 2018).

In Germany, since 2024, there has been a legal

obligation for all regional medical counselling fa-

cilities to provide public quality reporting. Conse-

quently, all medical facilities that provide both inpa-

tient and outpatient care are required to implement a

nationwide quality assurance plan (cf. (Petzold et al.,

2021)).

In the context of quality assurance, peer reviews

represent the prevailing instrument for the assessment

of the reliability of medical reports in Europe. This

also applies to the regional advisory institutes of the

Medical Advisory Boards. In contrast to the majority

of other peer reviews, the procedure employed by the

Medical Advisory Board (MD) comprises a minimum

of three stages for a randomly selected sample:

1. Internal assessment by a peer from the regional

counselling institution

2. External assessment by a second peer from an-

other medical service

3. Possible change to the internal assessment based

on the external result

In the event of a discrepancy between the internal

and external assessments following step 3, the medi-

cal report is submitted to the fourth step of the quality

assurance process, the consensus conference.

928

Ries, V., Schuster, R., Menz, P.-U., Thiele, K.-P., van Treeck, B. and Burmester, M.

Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in

Germany.

DOI: 10.5220/0013376700003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 928-935

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Table 1: Abbreviations for the individual medical fields.

Label Medical field

100 Incapacity of work

200 Hospital care

400 Methods/ pharmacy

500 Prevention and rehabilitation

700 Medical supplies

BHF Factual or putative diagnosis treatment errors

S00 Plastic/obesity surg./ transsexual / hospice care

Z00 Dentistry

4. An objective evaluation conducted by a panel of

impartial third parties who were not involved in

the assessment of the medical opinion in question

If there is no consensus at the conclusion of the

fourth step, the final quality assurance step is under-

taken:

5. Discussion among all consensus conference par-

ticipants and final vote on the result

The process described here is only applicable to a

significant random sample of the reports, as the un-

dertaking of an external review necessitates the in-

vestment of additional time. Irrespective of whether

a single or double check is conducted, the entire pro-

cess, from data collection to final quality assurance, is

carried out in a fully digital and anonymised manner

via an IT-supported procedure. The distinctive quality

assurance workflow outlined herein presents a novel,

nationwide perspective. The regular consensus con-

ferences provide a forum for exchanging views on the

quality assessment, visualising the different degrees

of rigour in the assessment of a medical report, and,

through discussion among the peers, promoting the

appropriate rigour of the assessment, see (Wirtz and

Caspar, 2002), (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994) and

(Chaffer et al., 2019).

There are a total of nine different medical fields

in which the quality assurance of the expert opinions

takes place:

The evaluation of medical reports across all med-

ical fields is based on a review of 20 essential cri-

teria, called Quality Criteria (QC). These 20 criteria

are systematically organised into four distinct subject

groups, as follows:

• Structure and completeness

• Understandability, plausibility and traceability

• Social medical guidlines

• Privacy and confidentiality

Forthermore it is possible to supplement the 20

quality criteria with subject-specific assessment cri-

teria. The peer has three options for each of these

criteria:

• green : QC isfulfilled

• yellow : QC has potential for improvement

• red : QC is not sufficiently fulfilled

If the peer chooses the colour yellow or red, they

are obliged to give reasons for their decision, see

(Ries et al., 2020), (Ries et al., 2023).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

This analysis includes an evaluation of 52,136 indi-

vidual case assessments conducted during the imple-

mentation of the nationwide quality assurance con-

cept. The total number of appraisals subjected to anal-

ysis is 42,736 internal and 9,459 external appraisals.

The period under analysis varies according to the

medical fields. The period from 2021 to 2023 was

subjected to analysis for the medical fields 100, 500,

700, BHF and Z00. The integration of medical fields

300 and S00 into the quality assurance process oc-

curred only in 2022, resulting in the analysis of only

two years’ worth of data. The latest iteration of the

medical field NUB was introduced in 2023. In subse-

quent analyses, a distinction is made between the nine

medical fields.

Ensuring quality necessitates the design of an ef-

ficient and meaningful reviews. Of particular rele-

vance is the independence of the evaluation of indi-

vidual quality criteria from one another. To this end,

a preliminary step involves the analysis of various en-

tropy scales to visualise the evaluation behaviour of

the medical expert groups. As part of this analysis,

the Shannon entropy, the descriptive parameter λ of

the Poisson distribution and the Gini coefficient are

examined.

The Shannon entropy is defined by

E(p

1

, p

2

, ..., p

n

) = −

n

∑

i=1

p

i

ln(p

i

).

Where p

i

, i = 1, ..., n denotes the probability that ex-

actly i criteria were rated as ’red’. If p

i

= 0, 0 ·

ln(0) := 0 is defined. The Shannon entropy is a mea-

sure of the disorder of the data, see (Jaynes, 2003)

and (Ostermann and Schuster, 2015). A low entropy

is therefore advantageous as it minimises disorder.

In order to test the data for a Poisson distribution

(Jaynes, 2003), it is necessary to obtain an estima-

tor for the parameter λ. The estimator for the param-

eter λ is determined using the parameter estimation

in Mathematica at Wolfram Research for the Poisson

distribution. A small value is preferable, as this re-

sults in a faster decrease in the curve. Subsequently, a

Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the

Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in Germany

929

chi-square test is conducted for all medical fields at a

significance level of 5%.

As defined in (Dorfman, 1979)the Gini coefficient

describes the extent of deviation from a uniform dis-

tribution. The Gini coefficient can be calculated as

the area between the Lorenz curve and the bisector,

which represents a uniform distribution. The Lorenz

curve illustrates the proportion of errors in relation to

the number of analyses. Accordingly, high values of

the Gini coefficient are to be preferred, as this min-

imises disorder, see (Dorfman, 1979), (Jaynes, 2003)

and (Ostermann and Schuster, 2015).

Subsequently, the correlations between the param-

eter λ and the entropy for the QCs rated ’red’ are

subjected to analysis. Furthermore, those QCs for

which potential for improvement was identified are

analysed. The aim is to analyse the differences in in-

dividual entropy scale values.

A current topic of interest is the comparison of the

regional and the nationwide double-checked evalua-

tion of the expert reports. In this context, the entropy

and the parameter λ for the number of red/green dif-

ferences between the internal and external assessment

within a medical report are compared. Finally, the

correlation between the two entropy scales is analysed

with regard to the red/green and yellow/green ratings

of the internal and external peers.

This is followed by a cluster analysis between the

quality criteria in order to determine which criteria are

often rated similarly in the individual medical fields

and could therefore possibly be summarised. In this

context, criteria that are only used in one medical area

or are mentioned in contradictory reports are not taken

into account due to limited information.

In order to achieve this, a difference counter is in-

troduced for each combination of criteria. In the event

that the discrepancy between the ratings of two crite-

ria within an expert opinion is minimal (red/yellow or

yellow/green), the difference counter is incremented

by one. In the event of a discrepancy between the

’red’ and ’green’ criteria, the difference counter is in-

creased by two. Subsequently, the total values are cal-

culated by aggregating the determined values across

all expert opinions. For each criterion, the top 1 and

the top 2 other criteria are then selected, which in

combination have the smallest difference counter. For

the purposes of visualisation, the criteria are repre-

sented as corner points on a graph, with the edges

describing the smallest evaluation differences. The

graphs are visualised using the software Mathematica,

developed by Wolfram Research. Mathematica is also

used to determine the community clusters. An opti-

misation process is employed to identify subgraphs

with minimal interconnectivity and high intrasub-

Table 2: Entropy, lambda and the Gini coefficient in med-

ical fields for the quota of regional and nationwide fulfill

assessment

Medical

entropy lambda λ

Gini

Field coefficient

100 0.3433 0.4033 0.8590

200 0.1512 0.1189 0.9419

300 0.1930 0.1959 0.9410

400 0.2042 0.1956 0.9350

500 0.3136 0.3500 0.8755

BHF 0.0925 0.0730 0.9740

S00 0.2626 0.2751 0.9040

Z00 0.2203 0.2140 0.9176

graph connectivity. For an overview of the method-

ological and logical background, please refer to the

cited studies, as follows: (Alon, 1998), (Brooks,

1991), (Buser, 1978), (Chakrabarti and Faloutsos,

2006) und (Chung, 1997).

Finally, the alterations in assessments across the

five stages of the quality assurance procedure are ex-

amined. In order to exclude potential confounding

factors such as divergent medical expertise and expe-

rience in writing medical reports, the medical fields

100 and 200 have been selected. Field 100 represents

all areas in which the reports are prepared prospec-

tively while the patients are undergoing acute med-

ical treatment. In contrast, the medical field 200

represents the retrospective reports. Both medical

fields have an identical duration and already included

a quality assurance procedure prior to the implemen-

tation of the nationwide quality assurance plan. In or-

der to ensure the comparability of the data, only those

internal ratings for which a nationwide rating is avail-

able are included in the subsequent analyses.

3 RESULTS

The three measures of disorder illustrated in Table 2

yield identical results.

The best ratings, characterised by low entropy and

a high Gini coefficient, can be observed in the medical

areas 200 and BHF. This leads to the conclusion that

these expert groups tend to choose between the poles

‘green’ and ‘red’ in their assessment. It is evident that

these medical fields show clear guidelines for medi-

cal assessment, which were well implemented in all

15 regional counselling facilities. In contrast, the spe-

cialities 100 and 500 show the highest entropy and

the smallest Gini coefficient. This demonstrates that

despite binding assessment guidelines, there is con-

siderable room for judgement.

For the given data, a Poisson distribution for all

medical areas could not be rejected with a chi-square

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

930

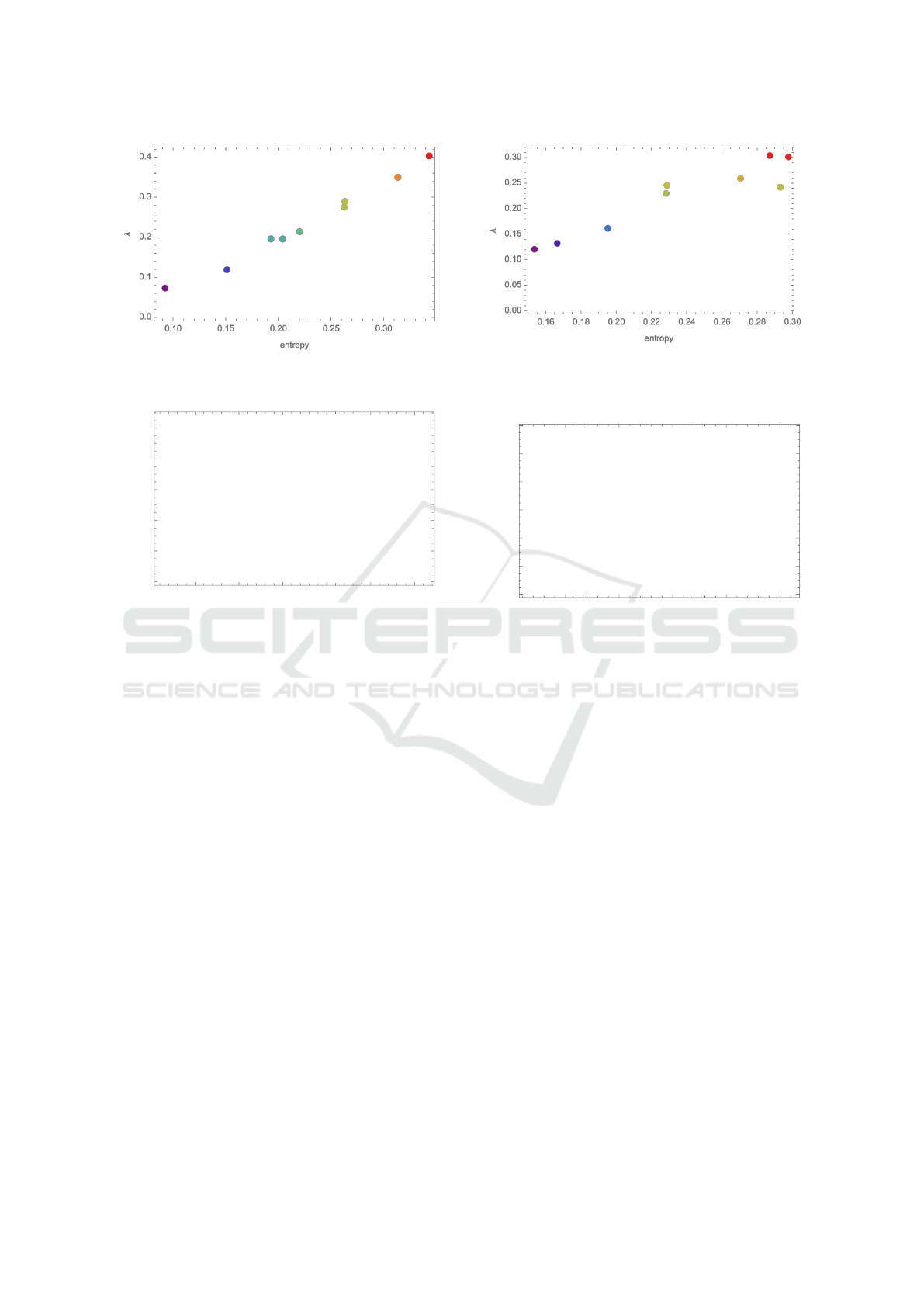

Figure 1: Laplace parameters and entropy for medical fields

under the aspect of ‘prerequisites are not fulfilled’.

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.35 0.40 0.45 0.50 0.55 0.60

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

entropy

λ

Figure 2: aplace parameters and entropy for medical fields

with regard to the ‘improvement potential’.

test at a significance level of 5%. Consequently, λ can

be interpreted as the rate of decline.

A correlation of r

2

= 0.9882 was observed be-

tween the two measures entropy and λ. Furthermore,

there is a high correlation between entropy and the

one minus Gini coefficient, with the value for the cor-

relation being almost 1 (r

2

= 0.9647). The use of the

‘one minus’ is necessary to ensure a consistent direc-

tion of change. Despite the very different definitions

of the distribution measures, there is a very high de-

gree of agreement between all of them.

Figure 1 illustrates the correlation between the

Laplace distribution and the Shannon entropy for all

nine medical specialities, with a particular focus on

cases marked in red.

Figure 2 shows the same for the ‘improvement po-

tential’ (yellow ratings). The distribution can be di-

vided into three clusters.

A comparable pattern is observed in the deviation

measures and their correlation for the differences be-

tween internal (same medical advisory institution as

the medical expert opinions) and external assessments

(different medical advisory institution). Figure 3 il-

lustrates the distribution of the number of assessments

classified as ’prerequisites are not met’ (red) and ’cor-

Figure 3: Laplace parameters and entropy for all nine med-

ical fields in relation to the differences between ‘red’ and

‘green’, internal and external assessments.

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

entropy

λ

Figure 4: Laplace parameters and entropy for all nine med-

ical fields in relation to the differences between ’green’ and

’yellow’ and between ’yellow’ and ’red’ ratings in relation

to internal and external ratings

rect’ (green) across all criteria in a medical opinion.

The two measures demonstrate a correlation coeffi-

cient of r

2

= 0.9885.

The two best matches are identified within the

medical field with the highest ratings, though with

significant differences in the ratings. In contrast to the

pattern described above, the most critical ratings in

the medical field ‘Prevention and rehabilitation (500)’

are replaced by ‘Medical supplies (700)’.

The same applies to the external assessment en-

tropy results, as the ‘Medical supplies (700)’ repre-

sents recommendations on cost coverage for highly

complex and expensive healthcare services provided

as part of case management for an individual patient.

The lesser rating discrepancies between the cate-

gories ’green’ and ’yellow’ and between ’yellow’ and

’red’ can be demonstrated through a distribution pat-

tern, as illustrated in Figure 4 with a correlation coef-

ficient of r

2

= 0.9913.

In order to enhance the efficacy of decision-

making processes, the interconnections between the

quality criteria at the neighbourhood level are sub-

Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the

Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in Germany

931

1

14

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

16

10

11

12

15

17

18

20

Figure 5: Top 1 community cluster in the assessment be-

tween the quality criteria in the medical field 100.

1

14

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

16

10

11

12

15

17

18

20

Figure 6: Top 1 community cluster in the assessment be-

tween the quality criteria in the medical field 500.

jected to analysis. In the top one cluster for the med-

ical fields 100 and 500, three quality criteria form a

cluster. The aforementioned criteria are as follows:

• QC 9: The medical report contains the informa-

tion required to assess the medical question in

question

• QC 15: The medical report takes into account the

socio-medical requirements for medical reports in

this area (e.g. assessment guidelines etc.)

• QC 16: The medical reports are plausible and

comprehensible in view of the facts presented

These quality criteria are close to each other in

terms of medical substance. Indeed, it has been

demonstrated that quality criterion 9 is a critical el-

ement in the evaluation of the quality of a medical

report. An expert opinion that does not satisfy this

criteria set forth is deemed to be of lesser substance,

and the assumption of costs for the pertinent health-

care service is not advised.

Moreover, quality criteria 1 (question about statu-

tory health insurance) and 14 (medical assessment

uses current medical knowledge) demonstrate a high

level of agreement in the evaluation, although they

show significant differences in terms of content (see

Figure 5 and Figure 6).

In the medical field 200, the content-related qual-

ity criteria 9, 15 and 16 can again be summarised

in a cluster with the two additional quality criteria

2 (the documents on which the assessment is based

1

11

2

4

3

5

7

8

9

10

12

14

15

16

17

18

20

Figure 7: Top 1 community cluster in the assessment be-

tween the quality criteria in the medical field 200.

are named) and 4 (information on the medical field

and the result of the medical specialist assessments

are correctly coded).

The second cluster comprises all criteria that are

the least distant from criterion 1, which addresses the

issue of statutory health insurance. Criterion 4 in the

first cluster is also among these. Although these differ

from criterion 1 in various ways, no other criterion

is as central to the graphs as illustrated in Figure 7.

However, this is primarily due to the particularly high

proportion of agreement in the evaluation.

A high relevance of a solid information base (QC

9) can also be derived for the medical field 200 in or-

der to achieve a convincing result (QC 16) of a medi-

cal expert opinion.

The 9/16 linkage can be observed in all medical

fields analysed so far (100, 200, 300, 500), which

are presented here, as well as in two other medi-

cal fields. This applies with the exception of factual

or alleged diagnostic treatment errors (BHF), which

show a completely different pattern. Quality criterion

15, which stipulates that the medical assessment must

take into account the socio-medical requirements of

the patient, occupies a central position and is closely

related to criterion 1, which includes the question of

statutory health insurance. This is shown in Figure 8.

If the question is formulated correctly (criterion

1), the result is optimal, taking into account all socio-

medical requirements (criterion 15). Prior to this

study, the relevant medical expert group, with ex-

tensive experience in quality assessment, had already

designed QC 1 in such a way that no abbreviations

or coding of the medical question were permitted.

Instead, the medical question in the medical expert

opinion had to be rephrased word for word. Con-

sequently, the significant dependence between QC 1

and QC 15 can be demonstrated in an objective and

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

932

1

15

2

3

4

5

7

8

9

10

11

12

14

16

17

18

20

Figure 8: Top 1 community cluster in the evaluation be-

tween the quality criteria in the medical field of ‘actual or

alleged diagnostic treatment errors (BHF)’.

scientific manner.

In a second cluster, only two criteria are included:

4 (information on the medical specialty and result of

the medical reports are correctly coded) and 8 (the

medical report is easy to read in terms of its linguistic

design: orthographic and grammatical correctness as

well as the use of abbreviations).

In general, medical reports must be sufficiently

comprehensible to be interpreted accurately by health

insurance fund personnel who possess expertise in

clinical case management. In contrast, in cases of

actual or alleged diagnostic treatment errors (BHF),

the medical reports serve as expert evidence in social

court proceedings. In such cases, the contents must

be understood by the judge without specialised medi-

cal knowledge. In this highly developed medical field,

the translation of medically sound analysis of medical

diagnosis and treatment procedures into non-medical

language represents a constant challenge.

The challenge under discussion here is identical to

the 8/4/1 cluster. The number 8 represents linguistic

abilities and perceptibility, the number 4 denotes the

coded result, and the number 1 signifies the explicitly

reformulated question(s) to be considered.

Next, the two most significant neighbourhood re-

lationships are examined. To ensure better visuali-

sation of the criteria that are adjacent to most of the

other criteria, the community clusters are not marked.

This represents a further optimisation of the presenta-

tion method by Mathematica.

In consideration of the established quality criteria,

a 9/16 link can be substantiated for the majority of

medical fields, including 100, 200, 300, and 500. In

contrast, diagnostic treatment errors (BHF) exhibit a

wholly distinct pattern.

In the context of medical area 100, criteria 1

(question about statutory health insurance) and QC 14

(medical assessment utilises the current state of med-

ical knowledge) are of central importance.

Once more, criteria 9 (the medical assessment

contains the information necessary to assess the facts

of the case) and 16 (the medical assessment is plausi-

ble and comprehensible in view of the facts presented)

1

14

3

2

4

5

7

8

9

16

12

10

20

11

15

17

18

Figure 9: Top 2 community clusters in the evaluation be-

tween the quality criteria in the medical field 100.

1

14

20

2

3

4

12

5

7

8

9

16

10

11

15

17

18

Figure 10: Top 2 clusters in the evaluation between the qual-

ity criteria in the medical field 500.

are in close proximity to one another.

It can be observed that Criterion 16 leads back to

criterion 15 (the medical expertise assessment takes

into account the socio-medical requirements). From

criterion 16, one edge of the graph leads to criterion

12 (the presentation of the medical expertise assess-

ment is coherent with the question).

In the context of the medical field 500, criteria 1

and 14 are again the focus of the graph, while criteria

9 and 16 are situated in a mutual position with a high

degree of mutual proximity in the graph. The same

group of socio-medical experts provides guidance on

the medical fields 100, 300 and 500. It is therefore of

significant interest that the assessments are similar.

In the medical field 200, criteria 1 and 11 (the

medical expertise dispenses with assumptions and

subjective assessments) are situated centrallly in the

graph, in crontrast to their positioning in medical

fields 100 and 500, where they are represended by QC

1 and QC 14, respectively. Additionaly, criteria 9 and

16 are again in the reciprocal position of great mutual

proximity in the graph. In the medical field 200, ad-

vice is provided by a different group of socio-medical

experts.

The consensus process has an impact on the re-

sults of the internal assessment already carried out.

The changes shown in Table 5 can be observed in area

100, which represents the prospectively prepared re-

Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the

Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in Germany

933

1

11

18

2

4

3

5

7

8

9

16

10

12

14

15

17

20

Figure 11: Top 2 community clusters in the rating between

the quality criteria in the medical field 200.

Table 3: Rating changes between the internal rating and the

end of the consensus procedure in a medical area 100 in %.

Internal Consens

Rating

green yellow red green yellow red

Group

Structure

94.3 2.9 2.8 92.8 4.2 3.0and

completeness

Under-

88.8 9.0 2.2 85.5 10.4 4.0

standability

plausibility

and

tracebility

Social

88.2 8.6 3.2 82.8 14.5 2.7medical

guidelines

Privacy

92.8 5.3 1.9 93.8 5.3 0.9and

confidentiality

Medical

77.6 16.0 6.4 69.6 22.6 7.9

filed

-

specific

rating

ports.

Equivalently, the changes between step 1 and step

5 of medical group 200 as a representative for the ret-

rospective expert reports in Table 4.

The pre-existing internal rating (depicted on the

left side) and its changes during the consensus con-

ference (depicted on the right side) reflect the be-

havioural pattern of the various peer groups in a re-

markably consistent way. The retrospective expert

group presents arguments against changes to its previ-

ous assessment, resulting in the green ratings remain-

ing almost unchanged, while the red ratings are either

maintained or even reduced.

The expert group for prospective assessments,

which was already required to exercise a greater de-

gree of judgement in a less homogeneous medical

field in its earlier assessments, enters the consensus

conference with a larger number of yellow ratings

than the expert group for retrospective assessments.

and in the consensus conference the medical experts

Table 4: Rating changes between the internal rating and the

end of the consensus procedure in a medical area 200 in %.

Internal Consens

Rating

green yellow red green yellow red

Group

Structure

97.5 2.0 0.6 96.6 2.3 1.0and

completeness

Under-

96.8 2.5 0.7 96.4 2.7 1.0

standability

plausibility

and

tracebility

Social

96.6 2.3 1.2 95.7 3.6 0.7medical

guidelines

Privacy

98.4 1.2 0.4 98.9 1.1 0.0and

confidentiality

Medical

98.6 0.6 0.8 99.3 0.4 0.4

filed

-

specific

rating

tend to conclude the discussions with even more yel-

low points. This indicates that the medical situations

to be assessed in prospective expert opinions may be

categorised with less clarity.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The use of the five-step procedure has proved ben-

eficial, as the peer discussion clearly identifies re-

gional differences in the handling of specific med-

ical or methodological issues. Possible questions

are assigned to the relevant committee to guide the

decision-making process on outstanding issues.

The documents are primarily provided by the

health insurance fund to which the patient has ap-

plied. For data protection reasons, only the regional

advice centre has access to the electronic patient file.

Inspection by the external medical service is not pos-

sible. This can be a potential problem because the

medical officer does not have all the necessary docu-

ments. Regular workshops are therefore held with the

nationwide Medical Adivisory borads to optimise the

flow of information. The new quality assurance sys-

tem also helps to identify organisational deficits in all

medical advice centres.

The discrepancy between the different medical

specialities can be divided into two subgroups. One

group conducts an ex-post evaluation, usually six

months after the patient has been discharged from

hospital or after the diagnostic or therapeutic inter-

vention has been completed. The second group evalu-

ates case management during the patient’s acute med-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

934

ical treatment. This allows for more flexibility in the

evaluation, as the case protocol is individualised at a

specific point in time on a still active treatment time-

line.

The new nationwide perspective of the workflow

promotes the visualisation and traceability of dis-

parate assessment patterns. The result is an improve-

ment in quality of a joint, learning expert system in

which the assessments of expert reports are increas-

ingly harmonised at federal level.

In addition, three factors were identified that could

potentially impede acceptance among the experts in-

volved.

1. Heterogeneity of the group of experts involved

2. The complexity of the medical specialty in ques-

tion, coupled with the rarity of the medical issues

it addresses

3. Familiarity of the peers with the new quality as-

surance plan and the associated procedures

REFERENCES

Alon, N. (1998). Spectral techniques in graph algorithms.

In Latin American Symposium on Theoretical Infor-

matics, pages 206–215. Springer.

Beauchamp, T. L. and Childress, J. F. (1994). Principles of

biomedical ethics. Edicoes Loyola.

Brooks, R. (1991). The spectral geometry of k-regular

graphs. J. Anal. Math, 57:120–151.

Buser, P. (1978). Cubic graphs and the first eigenvalue of a

riemann surface. Mathematische Zeitschrift, 162:87–

99.

Chaffer, D., Kline, R., and Woodward, S. (2019). Being

fair. supporting a just and learning culture for staff and

patients following incidents in the nhs.

Chakrabarti, D. and Faloutsos, C. (2006). Graph mining:

Laws, generators, and algorithms. ACM computing

surveys (CSUR), 38(1):2–es.

Chung, F. R. (1997). Spectral graph theory, regional con-

ference series in math. CBMS, Amer. Math. Soc.

Dorfman, R. (1979). A formula for the gini coefficient. The

review of economics and statistics, pages 146–149.

Jaynes, E. T. (2003). Probability theory: The logic of sci-

ence. Cambridge university press.

Nedopil, N. (2014). Qualit

¨

atssicherung bei der betreu-

ungsrechtlichen begutachtung. Forensische Psychia-

trie, Psychologie, Kriminologie, 1(8):10–16.

Nolting, H., Szczotkowski, D., and Kohlmann, T. (2016).

Qualit

¨

atssicherung im ambulanten d-arzt-verfahren.

Trauma und Berufskrankheit, 3(18):277–280.

Ostermann, T. and Schuster, R. (2015). An information-

theoretical approach to classify hospitals with respect

to their diagnostic diversity using shannon’s entropy.

In HEALTHINF, pages 325–329.

Petzold, T., Busley, A., Menz, P., Opitz, T., Ries, V.,

Rohland, D., Roth, B., Schuster, R., van Treeck,

B., Vogel, B., et al. (2021). Entwicklung eines

strukturierten qualit

¨

atssicherungsverfahrens f

¨

ur die

begutachtung von auftr

¨

agen zur gesetzlichen kranken-

versicherung in der gemeinschaft der medizinischen

dienste der krankenversicherung. Das Gesundheitswe-

sen, 83(08/09):199.

Polak, U., Wittwer, M., Szczotkowski, D., and Kohlmann,

T. (2018). Evaluation von durchgangsarztberichten

mithilfe eines peer-review-verfahrens. Trauma Beruf-

skrankh, 20(Suppl 4):S237–S240.

Ries, V., Thiele, K.-P., Schuster, M., and Schuster, R.

(2020). It-structures and algorithms for quality assur-

ance in the health insurance medical advisory service

institutions in germany. In HEALTHINF, pages 353–

360.

Ries, V., Thiele, K.-P., van Treeck, B., Schroeer, S., Witt,

C., and Schuster, R. (2023). It-structures and algo-

rithms for quality assurance in the medical advisory

service institutions in germany. step 2: To err is hu-

man. consensus-conferences. In HEALTHINF, pages

271–278.

Strahl, A., Gerlich, C., Alpers, G. W., Ehrmann, K., Gehrke,

J., M

¨

uller-Garnn, A., and Vogel, H. (2018). Devel-

opment and evaluation of a standardized peer-training

in the context of peer review for quality assurance in

work capacity evaluation. BMC medical education,

18:1–10.

Wirtz, M. A. and Caspar, F. (2002).

Beurteiler

¨

ubereinstimmung und Beurteilerrelia-

bilit

¨

at: Methoden zur Bestimmung und Verbesserung

der Zuverl

¨

assigkeit von Einsch

¨

atzungen mittels

Kategoriensystemen und Ratingskalen. Hogrefe.

Multidimensional Correlations in the Implementation in Medical Informatics and Their Statistical and Epidemiological Evaluations in the

Quality Assurance in the Medical Advisory Board in Germany

935