A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction

Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

Sonia Slimen

1,3

, Anis Mezghani

2,3

, Monji Kherallah

3

and Faiza Charfi

3

1

National School of Engineers of Gabes, University of Gabes, Tunisia

2

Higher Institute of Industrial Management, University of Sfax, Tunisia

3

Advanced Technologies for Environment and Smart Cities (ATES Unit), Faculty of Sciences, University of Sfax, Tunisia

Keywords: Machine Learning ML, EEG, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), fMRI (Functional MRI), Deep Learning,

sMRI (Structural MRI).

Abstract: Autism, often known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is characterized by a range of neurodevelopmental

difficulties that impact behavior, social relationships, and communication. Early diagnosis is crucial to

provide timely interventions and promote the best possible developmental outcomes. Although well-

established, traditional methods such as behavioral tests, neuropsychological assessments, and clinical facial

feature analysis are often limited by societal stigma, expense, and accessibility. In recent years, artificial

intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool. AI utilizes advanced algorithms to analyze a variety

of data modalities, including speech patterns, kinematic data, facial photographs, and magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI), in order to diagnose ASD. Each modality offers unique insights: kinematic investigations

show anomalies in movement patterns, face image analysis reveals minor phenotypic indicators, speech

analysis shows aberrant prosody, and MRI records neurostructural and functional problems. By accurately

extracting information from these modalities, deep learning approaches enhance diagnostic efficiency and

precision. However, challenges remain, such as the need for diverse datasets to build robust models, potential

algorithmic biases, and ethical concerns regarding the use of private biometric data. This paper provides a

comprehensive review of feature extraction methods across various data modalities, emphasising how they

might be included into AI frameworks for the detection of ASD. It emphasizes the potential of multimodal

AI systems to revolutionize autism diagnosis and their responsible implementation in clinical practice by

analyzing the advantages, limitations, and future directions of these approaches.

1

INTRODUCTION

People with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a

complicated neurological condition, face challenges

across various domains, including communication,

social interaction, and environmental awareness.

Common symptoms exhibited by individuals with

autism include repetitive behaviors, restricted

interests, and heightened sensitivity to sensory inputs.

These traits may manifest as difficulty interpreting

facial emotions, body language, and social norms.

While autism is typically diagnosed in childhood, its

impact extends into adulthood. With the correct

support and early interventions, people with autism

can lead more fulfilling lives and achieve better

integration into society.

Traditionally, behavioral observation and

diagnostic instruments like the DSM (Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) or the Autism

Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) have been

used to identify autism through behavioral

observation. While effective, these methods are time-

consuming and require specialized expertise. New

approaches to early and accurate autism identification

have been made possible by recent developments in

artificial intelligence (AI). Techniques such as

machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have

been employed to analyze speech patterns, kinematic

behaviors, and facial expressions. Support vector

machines (SVMs) and convolutional neural networks

(CNNs) are stand out for their ability to precisely

classify and identify characteristics linked to ASD.

One of the most promising methods for detecting

ASD is facial image analysis. According to research,

Slimen, S., Mezghani, A., Kherallah, M. and Charfi, F.

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources.

DOI: 10.5220/0013379600003890

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2025) - Volume 2, pages 849-860

ISBN: 978-989-758-737-5; ISSN: 2184-433X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

849

CNNs are able to recognise subtle differences in

autistic people's emotional reactions and facial

expressions. Simultaneously, magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) has proven invaluable a useful

technique for investigating brain abnormalities and

connection patterns linked to ASD. Diffusion tensor

imaging (DTI) and functional magnetic resonance

imaging (fMRI) have enable detailed analysis of brain

networks and their abnormalities in autistic people in

great detail. By identifying abnormal patterns of gaze

and visual attention often observed in individuals

with ASD, eye-tracking technology have

significantly enhanced diagnostic capabilities.

Beyond imaging, multimodal approaches offer a

comprehensive view of autism by integrating

information from multiple sources, such as kinematic

analysis, MRI scans, and facial expressions.

Kinematic investigations, for example, have shown

motor biomarkers that are suggestive of ASD, such as

repeated motions. Distinct prosodic and intonational

features that differentiate individuals with ASD from

neurotypical populations have been identified

through speech analysis, especially with CNNs.

Enables a more robust and accurate diagnostic

framework by integrating these many data sources.

With an emphasis on developments in ML and

DL methodologies and their application to image and

video data, this paper methodically examines ASD

detection techniques. The study looks at important

indications like:

• The accuracy of biological and behavioral

biomarkers for early identification of ASD.

• The effect on diagnostic accuracy of

multimodal data integration that combines eye

tracking, MRI, and facial imaging.

• How sophisticated AI models, such as CNNs

and transformers, enhance the categorisation and

identification of symptoms of ASD in actual clinical

situations.

The articles were selected based on strict

eligibility criteria. They were (i) written in English,

(ii) focused on image or video data, (iii) related to

autism in human populations, and (iv) utilized deep

learning- based techniques for feature extraction or

classification. Using keywords like autism spectrum

disorder, ASD detection, deep learning, and federated

learning, the search method includes queries across

major databases like PubMed, Scopus, Springer Link,

IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar. This rigorous

approach ensures that the review highlights the latest

and most relevant advancements.

There are six sections in our paper. An

introduction comes first, and then a thorough

literature review. We then discuss related research,

introduce the databases we used, then a discussion,

and wrap up with a summary of findings and future

research directions.

2

LITERATURE REVIW

2.1 History and Definition

The term "autism" was initially introduced by a Swiss

psychiatrist to describe symptoms associated with

schizophrenia, characterizing it as a form of childlike

thought aimed at escaping reality through fantasies

and hallucinations (Bleuler, E., 2012). Later, the term

gained prominence through the work of

Harris, J.

(2018)

, who introduced it into psychiatric

classification, describing it as a condition marked by

social disengagement and communication

difficulties, which he termed "Autistic Affective

Contact Disorder".

Kanner's work on autism led to significant debate

regarding its classification. Initially, autism was

considered an early form of schizophrenia and was

classified as a psychosis in children in subsequent

diagnostic manuals. Over time, similarities between

autism and schizophrenia were noted, especially in

2210 cases where individuals with autism exhibited

symptoms of schizophrenia (Canitano, R., 2017).

As understanding of autism improved, research

began to differentiate it from schizophrenia based on

symptomatic variations, family histories, and

treatment responses. This evolution led to the

inclusion of autism in diagnostic classifications

(Kolvin, I., 1971).

The classification of autism continued to evolve,

with the term "Pervasive Developmental Disorders"

(PDD) being used to refer to autism-like disorders.

Specific diagnostic criteria for these disorders were

later established (Sprock, J., 2014). The DSM-IV

categorized PDD-NOS into several disorders,

including Autism, Rett syndrome, Childhood

Disintegrative Disorder, Asperger disorder, and

Unspecified PDD (PDD-NOS) (Lewis, G., 1996).

The most recent revisions consolidated various

autistic disorders under the term "Autism Spectrum

Disorder" (ASD), recognizing the continuity of

symptoms and severity observed in individuals with

autism.

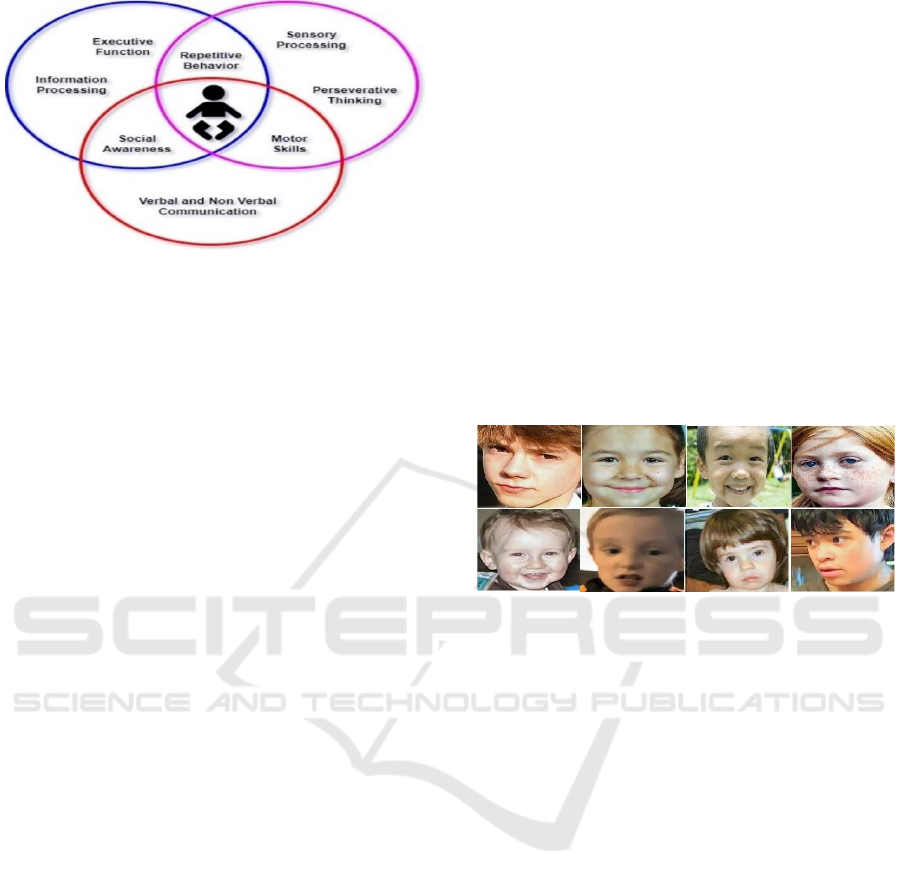

The primary behavioral and sensory markers

commonly seen in kids with autism spectrum

disorders are depicted in Figure 1.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

850

Figure 1: Typical Behavioral and Sensory Indicators of

Autism in Children.

Individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders,

such as autism and related conditions, may

experience notable deficits in their cognitive, social,

emotional, and behavioral development. Among

these conditions, Rett syndrome, formerly thought to

be a subtype of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is

now recognized as a distinct condition due to its

genetic origin, although it still shares some clinical

similarities with autism. Williams syndrome, a rare

genetic disorder, is distinguished by characteristic

facial features and mild to moderate intellectual

disability. The most common hereditary cause of

intellectual disability, fragile X syndrome, often

manifests as autism and is widely examined in

relation to ASD. Due to the wide range of ASD

symptoms, most autism research does not typically

focus on a single subtype.

Nonetheless, certain forms of autism, such as

high-functioning autism (formerly referred to as

Asperger's syndrome), are the topic of more focused

investigations, with an emphasis on those with

normal or above-average intelligence but notable

social challenges. The characteristics of the autism

spectrum are also shared by other conditions, such as

Prader-Willi syndrome, which is marked by eating

disorders and moderate to severe intellectual

handicap, and Angelman syndrome, which is

recognized for its happy demeanor and motor issues.

Additionally, some research emphasizes the

variability of autism by accounting for the range of

clinical symptoms within the spectrum. Finally,

Smith-Magenis syndrome, which is marked by

obsessive-compulsive behaviors and sleep

disturbances is frequently studied in relation to

emotion

recognition technologies, especially

in

studies on the machine learning-based identification

of autistic features.

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders

(ASD) often stand out due to significant differences

in their social interactions, particularly through facial

expressions and non-verbal behaviors. These

differences, although subtle, play a key role in

communication and the interpretation of emotions.

Indeed, individuals with autism tend to display more

neutral facial expressions, with a limited use of visual

cues to express or interpret emotions, which

complicates their identification. Thus, the observation

of facial expressions and eye movements becomes a

critical tool for understanding and diagnosing the

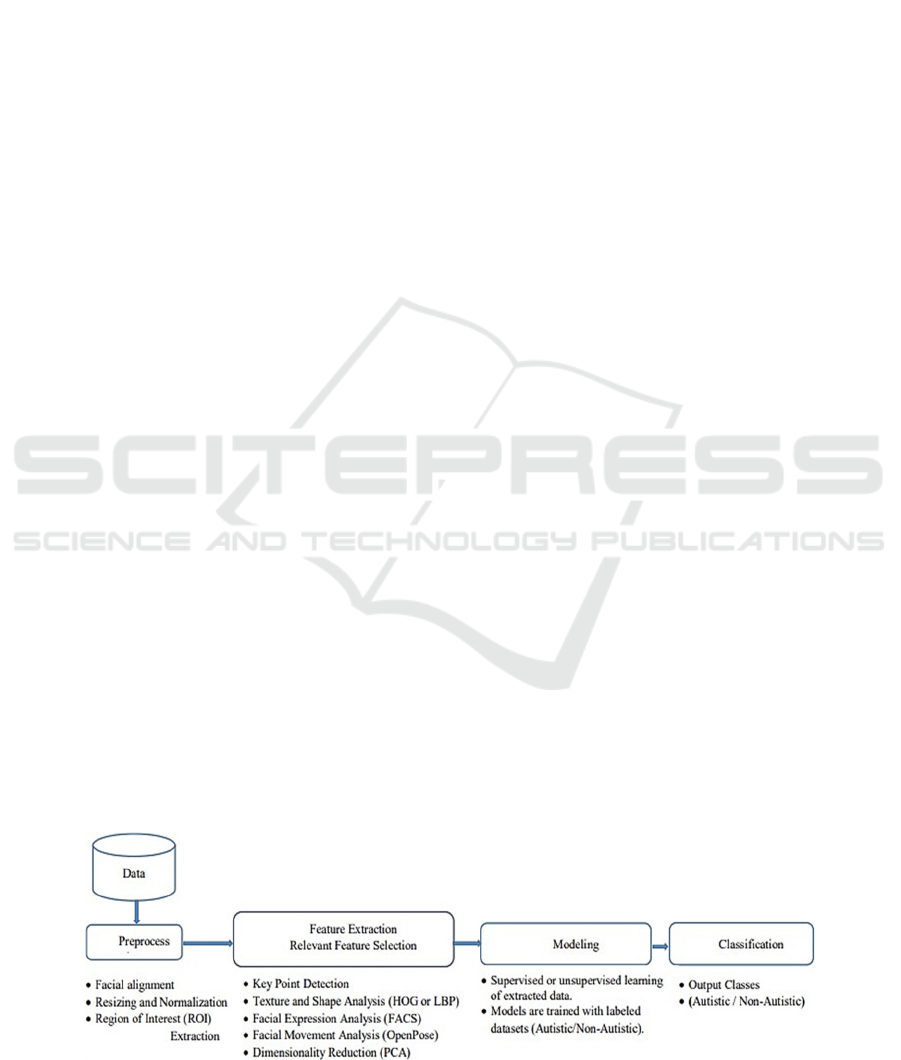

early signs of ASD. The face features of two child

groups are contrasted in Figure 2. Typical eye

movements, normal face symmetry, and

unambiguous facial expressions are characteristics

of children without autism spectrum disease (ASD).

Children with ASD, on the other hand, exhibit clear

distinctions, including less coordinated facial

expression patterns, aberrant gaze fixation, and

diminished emotional intensity.

Figure 2: The differences in facial features between

children without autism in the first row and children with

autism in the second row.

2.2 Related Work General Context of

Autism

Numerous methods including neurological,

behavioral, and physiological indicators are used in

autism screening procedures. Analysing the structure

and traits of the face is made possible by facial

features and landmarks, which are frequently used in

conjunction with the examination of facial

expressions to find subtle clues of emotional

variations. An objective and engaging way to

measure behavioral reactions is through robot-

evaluated systems. While methods like gaze analysis

and eye tracking aid in the understanding of social

interaction patterns, neurophysiological signals like

electroencephalograms (EEGs) offer information on

brain activity.

Simultaneously, standardized questionnaires and

thorough behavioral monitoring continue to be

essential components of clinical diagnostics. Action

analysis systems that interpret movements and social

interactions, as well as smartphone applications that

enable quick and easy detection, are examples of

technological developments. Last but not least,

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

851

neurological tests like brain MRIs provide a

biological perspective by detecting anatomical or

functional changes in the brain linked to autism

spectrum disorders. These methods, which are

frequently combined, improve diagnosis speed and

accuracy while opening the door to customised

solutions.

Autism detection in children has traditionally

relied on careful observation of their behavior and

comparison with established developmental reference

tools. These tools include the Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (SMD), the Autism Diagnostic

Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 2000),

the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI) (Lord et al.,

1994), the Autism Observation Scale Infant (AOSI)

(Bryson et al., 2008), the Autism Spectrum Screening

Questionnaire (ASSQ) (Ehlers et al., 1999), the

Children's Asperger Syndrome Test (CAST)

(Williams et al., 2005), and the .DSM-5 (Edition et

al., 2013). This process of comparison and

measurement requires considerable time and effort.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has

become increasingly important in various

applications, particularly in the early detection and

diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). AI

refers to the simulation of human cognition and

problem-solving through intelligent systems. At the

core of AI is ML which extracts information from

input databases using image preprocessing

techniques. The data is then classified or ranked using

either supervised or unsupervised learning methods.

Supervised learning employs classifiers such as

support vector machines (SVMs), random forests,

and traditional neural networks to categorize data

based on labeled input-output pairs.

In the medical field, deep learning (DL), a subset

of machine learning, is gaining popularity.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are the most

commonly used deep learning networks. There are

fully connected and include multiple convolutional

layers to perform tasks such as feature extraction and

classification. Conversely, unsupervised learning

does not rely on labeled input-output pairs, instead, it

classifies data based on patterns within the input data

itself.

2.3 Related Work

Recent advances in deep learning and machine

learning have transformed different fields such as

natural language processing (NLP) (Gasmi et al.,

2023, 2024), (Mezghani et al., 2024) and medical

diagnostic practice (Mezghani et al., 2024), offering

tools that are both accurate, fast and capable mainly

in autism detection. Several different techniques used

to identify autism, and each one significantly

advances the diagnosis. Techniques like Diffusion

Tensor Imaging (DTI) and structural MRI (sMRI),

which examine brain connectivity and structure, as

well as functional MRI (fMRI), which uses BOLD

methodologies to emphasize activity and functional

connectivity, have significantly advanced the use of

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging). The brain in

different cognitive states can be examined thanks to

these technologies. Finding brain biomarkers from

MRI and EEG data has been significantly enhanced

by ML and DL techniques. For instance, Pan et al.

(2021) used graph convolutional networks (GCN)

with an accuracy of 87.62%, whereas Yang et al.

(2019) used ASSDL on MRI data and obtained an

accuracy of 98.2%. The efficiency of these strategies

is demonstrated by multimodal approaches, such as

those explored by Tang et al. (2020) and cutting-edge

techniques like the Deep Belief Network (DBN)

optimised by the Adam War Strategy (AWSO) which

obtained 92.4% accuracy on the ABIDE dataset.

Furthermore, Park et al. (2023) created a model

integrating residual CNN and Bi-LSTM with self-

attention, which achieved 97.6% on ABIDE-I,

whereas Wen et al. (2022) employed multi-view

GCNs to reach an accuracy of 69.3%.

Simultaneously, the examination of emotions and

facial expressions provides a non-invasive way to

identify abnormal patterns linked to ASD. The

integration of neural networks and machine learning

techniques has been made easier by the challenges

that people with ASD have when it comes to

expressing and recognising their emotions. Wu et al.

(2021) investigated head movements and facial points

via OpenFace, while Hassouneh et al. (2020)

classified emotions with an accuracy of 87.25% using

LSTM-convolutional models. In order to enhance

emotional recognition, Cai et al., (2022) more

recently included attention techniques. Accuracy

ranges from 84% to 96% thanks to these efforts,

which combine face dynamics, gazes, and emotional

shifts with models like VGG19, MobileNet, and

Vision Transformers (ViT). Notably, the ViTASD-L

model was presented by Cao et al. (2023) and

achieved 94.5% accuracy on the Piosenka dataset.

Last but not least, privacy-preserving strategies that

use federated learning, as those by Shamseddine et al.

(2022), integrate behavioral and facial characteristics

while guaranteeing the security of personal

information.

Emerging techniques include eye tracking, which

examines gaze patterns to identify ASD early. The

accuracy of techniques developed by Atyabi et al.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

852

(2023) and Wei et al. (2021) that combine temporal

and spatial information has surpassed that of earlier

approaches. Similarly, to enhance categorisation,

Liaqat et al. (2021) and Wloka et al. (2017) employed

synthetic saccade models. Another potential

technique is kinematic analysis, which uses motor

impairments as biomarkers.

While Prakash et al. (2023) utilised R-CNN

models to study joint attention tasks and achieved

93.4% accuracy, Zhao et al. (2019) employed KNN

to analyse hand movements with an accuracy of

86.7%. YOLO-V5 and DeepSORT were coupled by

Ali et al. (2022) to track and categorise motions.

Lastly, speech and language-based detection looks at

linguistic and prosodic abnormalities that are

commonly seen in kids with ASD. With models like

CNNs (Ashwini et al., 2023) and SVMs (Nakai et al.,

2017), these studies take advantage of voice

spectrograms and linguistic data, exhibiting great

accuracy in this area because of machine learning.

3

FEATURE EXTRACTION

3.1 Feature Extraction for Facial

Recognition

Two primary types of facial features those linked to

emotion recognition and those related to eye

movement analysis are crucial in diagnosing autism.

Finding distinguishing characteristics in facial

expressions is essential in the field of emotion

recognition in order to identify emotional states like

happiness, sadness, or anger. For instance, Banire et

al. (2021) used the iMotions software to extract 34

face landmarks and utilized those cues to create

geometric features based on Euclidean distance

estimates. Conditional Local Neural Field (CLNF)

models have been utilised in several studies,

including those by Leo et al. (2018) and Del Coco et

al. (2017), to automatically analyse the facial

expressions of children with autism spectrum

disorders (ASD).In order to support the prediction of

behaviours associated with autism, sophisticated

techniques like OpenFace (Wu et al., 2021) make it

easier to extract key points, action units (AU), head

positions, and gaze orientations. Furthermore, by

extracting pertinent features, pre-trained

convolutional neural networks like AlexNet,

MobileNet, and Vision Transformers (ViT) (Slimani

et al., 2024) have demonstrated efficacy in

automatically segmenting and classifying facial

images. Furthermore, techniques like gesture analysis

and thermal imaging have been used to distinguish

children with ASD from those with typical

development (TD).

Gaze-related traits, which frequently show

abnormalities in children with ASD, offer important

hints for early identification. By combining the

temporal and spatial aspects of eye movements,

Atyabi et al. (2023) improved this method and

enhanced classification performance. The accuracy of

this study was further enhanced by Wei et al. (2021)

by integrating spatiotemporal data from gaze

trajectories.

Other cutting-edge studies, such as those by

Liaqat et al. (2021) and De Belen et al. (2021), have

either analyzed fixation sequences to find anomalies

or converted eye-tracking data into visual

representations. Additionally, recent research has

concentrated on emotional states like boredom or

dissatisfaction or on dynamic social interactions,

including head movements and eye contact (Chong et

al., 2017).

A schematic of models for autism detection that

concentrate on feature extraction from facial images

is shown in Figure 3.

3.2 Feature Extraction for Kinematic

Analysis

Certain motor biomarkers can help diagnose autism

spectrum disorders (ASD) more precisely.

Attention problems are often linked to complex motor,

Figure 3: Diagram of models for autism detection.

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

853

patterns including head motions, arm flapping, finger

trembling, and body shaking. Children with autism

may exhibit repetitive behaviors, such as shaking

their heads. Currently, motor deficits are considered

associated characteristics that lend credence to the

ASD diagnosis. According to recent studies, a better

comprehension of the motor deficits associated with

ASD could lead to for novel approaches to diagnosis

and treatment.

Patients with ASD can be differentiated from

those with typical development (TD) using kinematic

data. 20 kinematic features were derived from hand

gestures using kinematic analysis in a study with 16

participants with ASD and 14 with TD (Li et al.,

2017). Eight noteworthy characteristics were found

when these parameters were tested using the Naive

Bayes approach. Four methods were tested: Support

Vector Machine (SVM, both RBF and linear),

Random Forest, Decision Tree, and Naive Bayes.

SVM and Naive Bayes fared better than the other

algorithms, according to the results, with the linear

SVM showing the best results with 86.7% accuracy,

87.5% specificity, and 85.7% sensitivity.

Using machine learning techniques such as SVM,

LDA, Decision Tree, Random Forest, and K-Nearest

Neighbors (KNN), Zhao et al. (2019) enhanced the

diagnosis of ASD. Twenty-five children with high-

functioning autism and twenty-three typically

developing children participated in the study and

completed a variety of motor tasks. As markers of

limited kinematic properties, the researchers

computed the entropy and range of 95% of the

motion's amplitude, speed, and acceleration. With

88.37% precision, 91.3% specificity, 85% sensitivity,

and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.8815, the

KNN approach (k = 1) outperformed the other five

classifiers in terms of classification accuracy.

An important development in the assessment of

autism was the creation of the Autism Diagnostic

Observation Schedule (ADOS) by Lord et al. (2006).

This method looks for behavioral indicators of autism

by utilising unstructured observation tasks to look at

how kids react to various situations.

3.3 Feature Extraction for MRI

A key tool in the research of autism spectrum disorder

(ASD) is MRI, which provides unmatched insights

into the structure and function of the brain and enables

the identification of neurological biomarkers linked

to the disorder.

Both structural and functional neuroimaging data

have been widely used in recent studies on the

diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and

feature extraction is essential to processing and

interpreting these datasets for machine learning

applications. Structural imaging techniques, such as

diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (Travers, 2012) and

sMRI (Dekhil, O., 2020) are two structural methods

that reveal anomalies linked to ASD by shedding light

on brain connectivity and morphology. By using

blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD)

approaches to analyse brain activity and functional

connectivity, functional magnetic resonance imaging

(fMRI) enhances these investigations. Researchers

may examine how the brain functions in different

cognitive states using both task-based and resting-

state fMRI (rsfMRI).

The diagnosis of ASD has greatly improved with

the use of ML algorithms in conjunction with

neuroimaging data. For example, BOLD signals can

yield valuable information when functional MRI is

used in conjunction with methods like the General

Linear Model (GLM) and Independent Component

Analysis (ICA). Furthermore, the application of ML

and DL techniques to EEG and MRI signals makes it

easier to identify biomarkers linked to ASD,

including regional cortical thickness, grey matter

volume, and white matter (WM) volume. Studies like

Yang et al. (2019), which used ASSDL methods to

obtain a 98.2% accuracy on MRI data, and Pan et al.

(2021), which claimed an 87.62% accuracy with

graph convolutional networks (GCNs), serve as

examples of these developments.

Researchers improve the accuracy and

dependability of diagnosing ASD by customising

feature extraction methods to the unique properties of

MRI data, illustrating the interaction between cutting-

edge imaging technology and complex computational

methods.

3.4 Feature Extraction for Speech and

Language

Many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

struggle greatly with speech and language

comprehension, which frequently leads to ongoing

communication problems or no communication at all

after the age of two. These children may repeat words

or phrases without completely understanding their

meaning, and their voices may have an odd pitch or

rhythm when they do talk. A toddler may count from

one to five several times during a conversation that

has nothing to do with numbers, demonstrating how

speech can occasionally seem divorced from

conversational context. Many autistic children also

display echolalia, which is the immediate or delayed

repetition of previously heard words or phrases,

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

854

frequently accompanied by irrelevant enquiries.

Some autistic kids start conversations with cliches,

even with people they know, while others sing, talk

too much, or have a robotic voice. Another prevalent

trait is repetitive speech patterns.

These abnormal speech and language

characteristics linked to ASD have motivated

researchers to investigate machine learning (ML)

methods for assessment and classification, with

encouraging outcomes. Using 24 fundamental

frequency (F0)-based variables to measure pitch,

Nakai et al. (2017) used a Support Vector Machine

(SVM) to analyse single-syllable utterances in both

neurotypical (NT) and autistic participants,

outperforming traditional speech-language

pathologists in terms of accuracy.

In a similar vein, Hauser et al. (2019) classified

ASD in people between the ages of 18 and 50 using a

linear regression model with 123 audio features, with

a weighted accuracy of 0.83. SVMs were used by Lau

et al. (2022) to examine intonation and rhythmic

patterns in English and Cantonese speech, finding

that rhythmic features were only important in English.

Advanced approaches like Random Forests and

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have

significantly enhanced classification performance

beyond conventional machine learning techniques. A

CNN trained on spectrograms improved accuracy to

0.79. Plank et al. (2023) achieved a balanced accuracy

of 0.76 by using L2-regularized SVMs on phonetic

data that was extracted using the Praat tool. By

training SVM models on transcripts that contained a

variety of language variables from both NT and

autistic children, Ashwini et al. (2023) were able to

reach an impressive accuracy of 0.94.

Liu et al. (2022) extended this study by looking

into transformer-based models to find linguistic

patterns unique to ASD. The study used written

transcripts of adult conversations captured during

collaborative tasks and discovered that transformer

models performed noticeably worse for participants

with ASD than for those without ASD, indicating a

difficulty in representing the aberrant language of

autistic people. This disparity was ascribed to biases

in the training data, which were mostly drawn from

online and news sources and did not accurately

represent the distinct social-linguistic techniques used

by people with ASD.

These results highlight how machine learning and

deep learning techniques can be used to identify and

decipher the complex speech and language traits of

ASD, opening the door to more precise and non-

invasive diagnostic instruments.

3.5 A Multimodal Approach for

Enhanced Feature Extraction

People with ASD have abnormal gaze patterns, such

as avoiding eye contact and having different joint

attention in social situations, in addition to

neurological abnormalities. The direct measurement

of gaze behaviors and directed visual activities is

made possible by eye-tracking technology (ET),

which has been extensively employed in research on

attention allocation in individuals with ASD.

According to Nakano et al., (2010), for instance,

children with ASD spend less time observing faces

and social interactions than children who are

normally developing. Using an ET dataset, Liu et al.,

(2016) created a machine learning framework that

could classify children with ASD and TD with up to

88.51% accuracy.

In research on ASD, electroencephalogram (EEG)

and ET have been used separately to find useful

biomarkers and create diagnostic models with

cutting-edge machine learning techniques. However,

it is challenging to make a reliable diagnosis using

only unimodal data, like EEG or ET, because ASD is

complex and heterogeneous, showing up at both the

behavioral and cellular levels. Despite having

different viewpoints while ET captures behavioral

information and EEG reflects neurophysiological

activity these two modalities provide rich and

complementing data on ASD. However, it can be

difficult to directly identify the underlying

correlations and complementarities due to the

diversity of the data.

To address this challenge, multimodal fusion

emerges as a promising solution. This approach,

which has garnered increasing interest in the medical

field, has been applied not only to the diagnosis of

ASD but also to other diseases such as Parkinson's,

Alzheimer's, and depression. For example, Alexandru

et al., (2018) integrated EEG, fMRI, and DTI data to

characterize the autistic brain, while Mash et al.,

(2020) explored the relationships between fMRI and

EEG in spontaneous brain activity related to ASD.

Recent work, such as that of Vasquez-Correa et al.,

(2019), has shown that the fusion of multimodal data

can fully exploit the strengths of each modality while

compensating for their weaknesses, resulting in

improved diagnostic performance. Han et al., (2022)

combine electroencephalogram (EEG) and eye-

tracking data (ET) to present a novel multimodal

diagnostic approach for detecting autism spectrum

disorders (ASD) in children. Stacking denoising

autoencoders (SDAE) are used in this method to learn

and fuse features from both modalities.

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

855

This approach, which was tested on a dataset that

included 40 children with ASD and 50 normally

developing (TD) children, shows how

neurophysiological (EEG) and behavioral (ET)

perspectives complement each other. It achieved an

overall accuracy of 95.56%, with a sensitivity of

92.5% and a specificity of 98%. When compared to

unimodal and basic techniques, the experimental

findings demonstrate a substantial improvement, with

multimodal fusion enabling better separation of

ASD/TD groups.

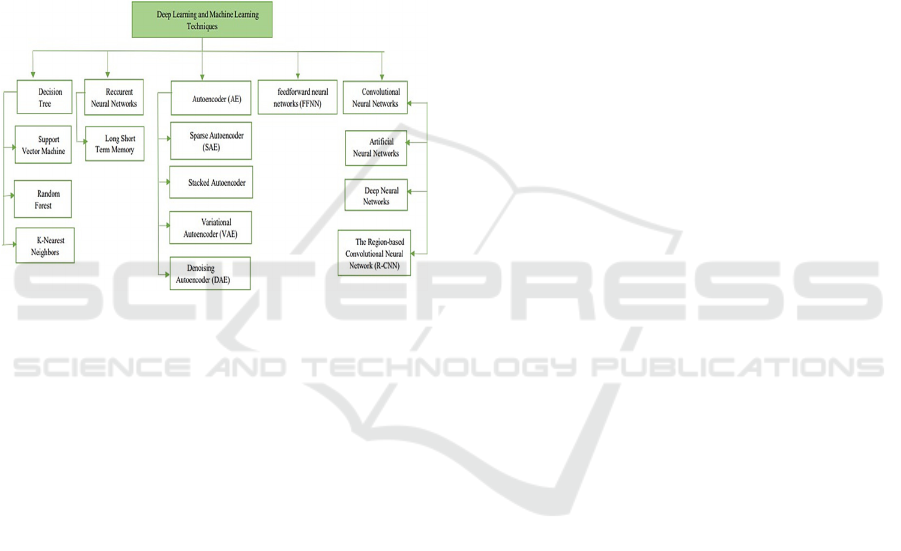

A diagram showing the various deep learning

(DL) techniques examined in this review is shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Diagram of diferents DL/ML-based approaches

considered in this review.

4

DATASETS

In this part, we examine in depth the different

databases public and private that are crucial to autism

research, emphasising their content, unique features,

and contributions to the development of autism

spectrum detection and analysis methods.

4.1 MRI Datasets

Significant disparities between people with ASD and

neurotypical participants can be identified thanks to

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a non-invasive

technique that creates three-dimensional anatomical

pictures. The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange

(ABIDE) (Di Martino et al., 2014, 2017) has collected

structural and functional brain imaging data from labs

worldwide in order to better understand the

neurological underpinnings of autism. Two

significant collections that are the outcome of this

effort are ABIDE I and ABIDE II. The initial version

of ABIDE I, which was released in 2014, combined

information from 17 different countries, comprising

1,112 resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI)

recordings with 539 participants with ASD and 573

neurotypical people between the ages of 7 and 64. A

more varied sample, consisting of 1,044 records,

including 487 participants with ASD and 593

neurotypical people, was added to the collection by

ABIDE II in 2017. Researchers can use these

databases as a useful resource to investigate the

neurological underpinnings of autism.

4.2 Visual Datasets

1Face and eye tracking datasets are essential for

identifying autism. Eye movement data from 28

children (with ASD and TD) was gathered using the

Tobii T120 eye tracker from 300 different visual

stimuli and is included in the Saliency4ASD (Duan et

al., 2019b). Chong et al. (2017) annotated 2 million

video images of 100 youngsters interacting with

adults to identify gaze, while Carette et al. (2018)

created a set of 547 photos translating dynamic eye

movements. In terms of facial data, Shukla et al.

(2017) gathered 1,126 facial images labelled by age

and gender, and Leo et al. (2018b) gathered videos of

17 kids displaying a range of emotions. Lastly, with

2,540 training images and a standardised reference

protocol, the Autism Facial Image Dataset (AFID)

(Piosenka, 2021) continues to be the only publicly

available database devoted to autism research using

facial images. These varied datasets provide a

valuable foundation for developing more precise and

reliable diagnostic tools. Once more, Rani, (2019)

gathered 25 pictures of people with ASD with four

different emotions (angry, neutral, sad, and cheerful)

from various online sources for their study.

4.3 Skeleton Datasets

The 2D/3D coordinates of the human joints make up

skeleton data. 136 participants with evenly dispersed

ASD and TD were included in a video collection of

social interaction created by Kojovic et al. (2021).

Later, they use OpenPose to extract the essential

elements from videos (Cao et al., 2017).

4.4 Multi Modal Datasets

Simple but frequently constrained by noisy data and

poor accuracy are unimodal systems, which employ a

single feature or modality to identify or assess autism

spectrum disorders (ASD) (Uddin et al., 2017). Multi-

modal data, which combines multiple sensor and

feature kinds, has been introduced to address these

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

856

issues. For instance, 128 children between the ages of

5 and 12 participated in 152 hours of multi-modal

interactions (audio, depth, and video) through robot

or adult-assisted activities in the De-Enigma dataset

(Shen et al., 2018). Similar to this, the DREAM

dataset (Billing et al., 2020) records 300 hours of

robot-assisted therapy for 61 children with autism. 3D

skeletons and metadata (such as age, gender, and

diagnosis) are extracted using RGB and RGBD

cameras. Additional datasets include those of Zunino

et al. (2018), which consists of 1,837 recordings of 40

children (autistic and neurotypical) doing gestures in

particular tasks, and Cai et al. (2022), which

examines videos of 57 children with ASD and 25

neurotypical children based on facial and movement

traits. Finally, to categorise repetitive behaviors like

spinning or flapping of the arms, the SSBD

(Rajagopalan et al., 2013) gathers 75 videos from

public platforms. The diagnosis of ASD and

behavioural analysis are made more accurate and

diverse by using multi-modal datasets.

5

DISCUSSION

The various feature extraction techniques used to

diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—

including facial recognition, kinematic analysis, MRI,

speech a n d language, multimodal data, and others—

emphasize how difficult it is to capture the complex

character of ASD. With machine learning techniques

like SVM and KNN attaining noteworthy

classification accuracies of up to 88.37% (Zhao et al.,

2019), kinematic analysis reveals motor biomarkers.

However, small sample sizes highlight the necessity

for more datasets to improve generalisation. With

sophisticated approaches like graph convolutional

networks reaching accuracies over 98%, MRI

techniques that make use of diffusion tensor imaging

(DTI) and functional MRI (fMRI) offer vital insights

into structural and functional abnormalities (Pan et

al., 2021). Similar to this, despite difficulties with

cultural heterogeneity and data biases, machine

learning methods such as CNNs can achieve up to

94% accuracy in speech and language feature

extraction, revealing linguistic patterns unique to ASD

(Ashwini et al., 2023). Although integration

complexity is still a problem, multimodal approaches

such as merging EEG and eye-tracking data have

shown greater diagnostic performance, with fusion

techniques obtaining accuracies of 95.56% (Junxia et

al., 2022). In the meantime, facial recognition

leverages sophisticated deep learning models like

Vision Transformers and tools like iMotions to

improve diagnostic accuracy by analysing eye

movements and emotions. Even though these

approaches have a lot of potential, issues with

scalability and accessibility, as well as ethical

concerns about data protection, need to be addressed.

In order to increase the precision and dependability of

ASD diagnosis, these findings collectively highlight

the necessity of interdisciplinary cooperation and the

creation of strong, affordable, and morally sound

multimodal diagnostic frameworks.

6

CONCLUSION

Our review of the literature focusses on various

feature extraction techniques and highlights

important advancements in the field of autism

identification. Among the approaches studied are

deep learning models, machine learning algorithms,

and conventional image processing techniques. The

ability of deep learning models to extract important

and complex aspects from a range of data, such as eye

movements, facial expressions, and brain signals, has

made them particularly promising.

However, problems persist in spite of these

advancements, particularly in the areas of accuracy,

model generalisation, and participant privacy

protection. Despite their significance, the size and

diversity limitations of the current datasets make it

difficult to build robust and inclusive models.

Using techniques like federated learning could be

a good solution for further study. This approach

would improve the security of sensitive data by

allowing models to be trained on decentralised data by

utilising information from several sources.

Furthermore, the use of multimodal data for example,

integrating facial, ocular, and brain signals could

significantly improve model performance by

capturing complementary information.

By paving the way for more inclusive, secure, and

reliable detection systems, these perspectives

contribute to our growing understanding and support

of autism.

REFERENCES

Alexandru Cociu, B., Das, S., Billeci, L., Jamal, W.,

Maharatna, K., Calderoni, S., ... & Muratori, F. (2018).

Multimodal Functional and Structural Brain

Connectivity Analysis in Autism: A Preliminary

Integrated Approach with EEG, fMRI and DTI. arXiv e-

prints, arXiv-1801.

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

857

Ali, A., Negin, F., Bremond, F., Thummler, S. (2022).

Video-based be- ¨ havior understanding of children for

objective diagnosis of autism, in: VISAPP 2022-

International Conference on Computer Vision Theory

and Applications.

Ashwini, B., Narayan, V., Shukla, J. (2023).Semantic and

Pragmatic Speech Features for Automatic Assessment

of Autism. In ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International

Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal

Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

Atyabi, A., Shic, F., Jiang, J., Foster, C.E., Barney, E., Kim,

M., Li, B., Ventola, P., Chen, C.H.

(2023).

Stratifcation of children with autism spectrum disorder

through fusion of temporal information in eye-gaze

scan-paths. ACM Transactions on Knowledge

Discovery from Data 17, 1–20.

Banire, B., Al Thani, D., Qaraqe, M., Mansoor, B., 2021.

Face-based attention recognition model for children

with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Healthcare

Informatics Research 5, 420–445.

Bleuler, E. (2012). Dementia praecox ou groupe des

schizophrénies. Epel Editions.

Bryson, S. E., Zwaigenbaum, L., McDermott, C.,

Rombough, V., & Brian, J. (2008). The Autism

Observation Scale for Infants: scale development

and reliability data. Journal of autism and

developmental disorders, 38, 731-738.

Canitano, R., & Pallagrosi, M. (2017). Autism spectrum

disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders:

excitation/inhibition imbalance and developmental

trajectories. Frontiers in psychiatry, 8, 69.

Cai, M., Li, M., Xiong, Z., Zhao, P., Li, E., Tang, J., 2022.

An advanced deep learning framework for video- based

diagnosis of asd, in: International Conference on

Medical Image Computing and Computer- Assisted

Intervention, Springer. pp. 434–444.

Cao, Z., Simon, T., Wei, S.E., Sheikh, Y., 2017. Realtime

multiperson 2d pose estimation using part afnity felds,

in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer

vision and pattern recognition, pp. 7291– 7299.

Cao, X., Ye, W., Sizikova, E., Bai, X., Coffee, M., Zeng,

H., & Cao, J. (2023). Vitasd: Robust vision transformer

baselines for autism spectrum disorder facial diagnosis.

In ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference

on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing(ICASSP)

(pp. 1-5). IEEE. Signal Processing (ICASSP) (pp. 1-5).

IEEE.

Carette, R., Elbattah, M., Dequen, G., Guerin, J.L., Cilia,

F., 2018. ´ Visualization of eye-tracking patterns in

autism spectrum disorder: method and dataset, in: 2018

Thirteenth International Conference on Digital

Information Management (ICDIM), IEEE. pp. 248–

253.

Chong, E., Chanda, K., Ye, Z., Southerland, A., Ruiz, N.,

Jones, R.M., Rozga, A., Rehg, J.M., 2017. Detecting

gaze towards eyes in natural social interactions and its

use in child assessment. Proceedings of the ACM on

Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous

Technologies 1, 1–20.

De Belen, R.A.J., Bednarz, T., Sowmya, A., 2021.

Eyexplain autism: interactive system for eye tracking

data analysis and deep neural network interpretation for

autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, in: Extended

Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1–7.

Dekhil, O., Ali, M., Haweel, R., Elnakib, Y., Ghazal, M.,

Hajjdiab, H., ... & El-Baz, A. (2020, July). A

comprehensive framework for differentiating autism

spectrum disorder from neurotypicals by fusing

structural MRI and resting state functional MRI. In

Seminars in pediatric neurology (Vol. 34, p. 100805).

WB Saunders

Del Coco, M., Leo, M., Carcagni, P., Spagnolo, P., Luigi

Mazzeo, P., Bernava, M., Marino, F., Pioggia, G.,

Distante, C., 2017. A computer vision based approach

for understandingemotional involvements in children

with autism spectrum disorders, in: Proceedings of the

IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision

Workshops, pp. 1401–1407.

Di Martino, A., Yan, C.G., Li, Q., Denio, E., Castellanos,

F.X., Alaerts, K., Anderson, J.S., Assaf, M.,

Bookheimer, S.Y., Dapretto, M., et al., 2014. The

autism brain imaging data exchange: towards a large-

scale evaluation of the intrinsic brain architecture in

autism. Molecular psychiatry 19, 659–667.

Di Martino, A., O’connor, D., Chen, B., Alaerts, K.,

Anderson, J.S., Assaf, M., Balsters, J.H., Baxter, L.,

Beggiato, A., Bernaerts, S., et al., 2017. Enhancing

studies of the connectome in autism using the autism

brain imaging data exchange ii. Scientific data 4, 1– 15.

Duan, H., Zhai, G., Min, X., Che, Z., Fang, Y., Yang, X.,

Gutierrez, ´ J., Callet, P.L., 2019b. A dataset of eye

movements for the children with autism spectrum

disorder, in: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Multimedia

Systems Conference, pp. 255–260.

Edition, F. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders. Am Psychiatric Assoc, 21(21), 591-

643

Ehlers, S., Gillberg, C., & Wing, L. (1999). A screening

questionnaire for Asperger syndrome and other high-

functioning autism spectrum disorders in school age

children. Journal of autism and developmental

disorders, 29, 129-141.

Gasmi, S., Mezghani, A., & Kherallah, M. (2023,

December). Arabic Hate Speech Detection on social

media using Machine Learning. In International

Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and

Applications (pp. 174-183). Cham: Springer Nature

Switzerland.

Gasmi, S., Mezghani, A., & Kherallah, M. (2024). SMOTE

for enhancing Tunisian Hate Speech detection on social

media with machine learning. International Journal of

Hybrid Intelligent Systems, 20(4), 355-368.

Han, J., Jiang, G., Ouyang, G., & Li, X. (2022). A

multimodal approach for identifying autism spectrum

disorders in children. IEEE Transactions on Neural

Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 30, 2003-

2011.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

858

Harris, J. (2018). Leo Kanner and autism: a 75-year

perspective. International review of psychiatry, 30(1),

3-17.

Hassouneh, A., Mutawa, A. M., & Murugappan, M. (2020).

Development of a real-time emotion recognition system

using facial expressions and EEG based on machine

learning and deep neural network methods.

Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 20, 100372.

Hauser, M., Sariyanidi, E., Tunc, B., Zampella, C., Brodkin,

E., Schultz, R. T., & Parish-Morris, J. (2019, June).

Using natural conversations to classify autism with

limited data: Age matters. In Proceedings of the

Sixth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical

Psychology (pp. 45-54).

Kojovic, N., Natraj, S., Mohanty, S.P., Maillart, T., Schaer,

M., 2021. Using 2d video-based pose estimation for

automated prediction of autism spectrum disorders in

young children. Scientific Reports 11, 1–10.

Kolvin, I. (1971). Studies in the childhood psychoses I.

Diagnostic criteria and classification. The British

Journal of Psychiatry, 118(545), 381-384.

Lau, J. C., Patel, S., Kang, X., Nayar, K., Martin, G. E.,

Choy, J., ... & Losh, M. (2022). Cross-linguistic

patterns of speech prosodic differences in autism: A

machine learning study. PloS one, 17(6), e0269637

Leo, M., Carcagn`ı, P., Distante, C., Spagnolo, P., Mazzeo,

P.L., Rosato, A.C., Petrocchi, S., Pellegrino, C.,

Levante, A., De Lume,` F., et al., 2018b. Computational

assessment of facial expression production in asd

children. Sensors 18, 3993.

Leo, M., Carcagn`ı, P., Del Coco, M., Spagnolo, P.,

Mazzeo, P.L., Celeste, G., Distante, C., Lecciso, F.,

Levante, A., Rosato, A.C., et al., 2018a. Towards the

automatic assessment of abilities to produce facial

expressions: The case study of children with asd, in:

20th Italian National Conference on Photonic

Technologies (Fotonica 2018), IET. pp. 1–4.

Lewis, G. (1996). DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. By the American

Psychiatric Association.(Pp. 886;£ 34.95.) APA:

Washington, DC. 1994. Psychological Medicine, 26(3),

651-652.

Li, B., Sharma, A., Meng, J., Purushwalkam, S., & Gowen,

E. (2017). Applying machine learning to identify

autistic adults using imitation: An exploratory study.

PloS one, 12(8), e0182652.

Liaqat, S., Wu, C., Duggirala, P.R., Cheung, S.c.S., Chuah,

C.N., Ozonof, S., Young, G., 2021. Predicting asd

diagnosis in children with synthetic and image-based

eye gaze data. Signal Processing: Image

Communication 94, 116198.

Liu, D., Liu, Z., Yang, Q., Huang, Y., & Prud’Hommeaux,

E. (2022, October). Evaluating the performance of

transformer-based language models for neuroatypical

language. In Proceedings of COLING. International

Conference on Computational Linguistics (Vol. 2022,

p. 3412). NIH Public Access.

Liu, W., Li, M., & Yi, L. (2016). Identifying children with

autism spectrum disorder based on their face processing

abnormality: A machine learning framework. Autism

Research, 9(8), 888-898.

Lord, C., Risi, S., DiLavore, P. S., Shulman, C., Thurm, A.,

& Pickles, A. (2006). Autism from 2 to 9 years of

age. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(6), 694-701.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E. H., Leventhal,

B. L., DiLavore, P. C., ... & Rutter, M. (2000). The

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A

standard measure of social and communication deficits

associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of

autism and developmental disorders, 30, 205-223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism

Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a

diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with

possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of

autism and developmental disorders, 24(5), 659-685.

Mash, L. E., Keehn, B., Linke, A. C., Liu, T. T., Helm, J.

L., Haist, F., ... & Müller, R. A. (2020). Atypical

relationships between spontaneous EEG and fMRI

activity in autism. Brain connectivity, 10(1), 18-28.

Mezghani, A., Slimen, S., & Kherallah, M. (2024). Skin

Lesions Diagnosis Using ML and DL Classification

Models. International Journal of Computer

Information Systems and Industrial Management

Applications, 16(2), 17-17.

Mezghani, A., Elleuch, M., Gasmi, S., & Kherallah, M.

(2024). Toward Arabic social networks unmasking

toxicity using machine learning and deep learning

models. International Journal of Intelligent Systems

Technologies and Applications, 22(3), 260-280.

Nakai, Y., Takiguchi, T., Matsui, G., Yamaoka, N., Takada,

S. (2017). Detecting abnormal word utterances in

children with autism spectrum disorders: machine-

learning-based voice analysis versus speech therapists.

Perceptual and motor skills, 124(5), 961- 973.

Nakano, T., Tanaka, K., Endo, Y., Yamane, Y., Yamamoto,

T., Nakano, Y., ... & Kitazawa, S. (2010). Atypical gaze

patterns in children and adults with autism spectrum

disorders dissociated from developmental changes in

gaze behaviour. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:

Biological Sciences, 277(1696), 2935-2943.

Pan, L., Liu, J., Shi, M., Wong, C. W., Chan, K. H. K.

(2021). Identifying autism spectrum disorder based on

individual-aware down-sampling and multimodal

learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.09129.

Park, K. W., & Cho, S. B. (2023). A residual graph

convolutional network with spatio-temporal features

for autism classification from fMRI brain images.

Applied Soft Computing, 142, 110363.

Piosenka, G., 2021. Detect autism from a facial image.

Plank, I. S., Koehler, J. C., Nelson, A. M., Koutsouleris,

N., & Falter-Wagner, C. M. (2023). Automated

extraction of speech and turn-taking parameters in

autism allows for diagnostic classification using a

multivariable prediction model. Frontiers in

Psychiatry, 14, 1257569.

Prakash, V.G., Kohli, M., Kohli, S., Prathosh, A., Wadhera,

T., Das, D., Panigrahi, D., Kommu, J.V.S. (2023).

Computer vision-based assessment of autistic children:

A Survey of Advanced Classification and Feature Extraction Techniques Across Various Autism Data Sources

859

Analyzing interactions, emotions, human pose, and life

skills. IEEE Access.

Rajagopalan, S., Dhall, A., Goecke, R., 2013. Self-

stimulatory behaviours in the wild for autism diagnosis,

in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference

on Computer Vision Workshops, pp. 755– 761.

Rani, P., 2019. Emotion detection of autistic children using

image processing, in: 2019 Fifth International

Conference on Image Information Processing (ICIIP),

IEEE. pp. 532–535.

Shamseddine, H., Otoum, S., & Mourad, A. (2022). A

Federated Learning Scheme for Neuro- developmental

Disorders: Multi-Aspect ASD Detection. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2211.00643.

. Shen, J., Ainger, E., Alcorn, A., Dimitrijevic, S.B., Baird,

A., Chevalier, P., Cummins, N., Li, J., Marchi, E.,

Marinoiu, E., et al., 2018. Autism data goes big: A

publicly-accessible multi-modal database of child

interactions for behavioural and machine learning

research, in: International Society for Autism Research

Annual Meeting.

Shukla, P., Gupta, T., Saini, A., Singh, P.,

Balasubramanian, R., 2017. A deep learning frame-

work for recognizing developmental disorders, in: 2017

IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer

Vision (WACV), IEEE. pp. 705–714.

Slimani, N., Jdey, I., & Kherallah, M. (2024). Improvement

of Satellite Image Classification Using Attention-Based

Vision Transformer. In ICAART (3) (pp. 80-87).

Sprock, J. (2014). DSM‐III and DSM‐III‐R. The

Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, 1-5.

Tang, M., Kumar, P., Chen, H., & Shrivastava, A. (2020).

Deep multimodal learning for the diagnosis of autism

spectrum disorder. Journal of Imaging, 6(6), 47.

Travers, B. G., Adluru, N., Ennis, C., Tromp, D. P.,

Destiche, D., Doran, S., ... & Alexander, A. L. (2012).

Diffusion tensor imaging in autism spectrum disorder:

a review. Autism Research, 5(5), 289-313.

Uddin, M., Muramatsu, D., Kimura, T., Makihara, Y., Yagi,

Y., et al., 2017. Multiq: single sensor-based multi-

quality multi-modal large-scale biometric score

database and its performance evaluation. IPSJ

Transactions on Computer Vision and Applications 9,

1–25.

Vásquez-Correa, J. C., Arias-Vergara, T., Orozco-

Arroyave, J. R., Eskofier, B., Klucken, J., & Nöth, E.

(2018). Multimodal assessment of Parkinson's disease:

a deep learning approach. IEEE journal of biomedical

and health informatics, 23(4), 1618-1630.

Wei, W., Liu, Z., Huang, L., Wang, Z., Chen, W., Zhang,

T., Wang, J., Xu, L. (2021). Identify autism spectrum

disorder via dynamic filter and deep spatiotemporal

feature extraction. Signal Processing: Image

Communication 94, 116195.

Wen, G., Cao, P., Bao, H., Yang, W., Zheng, T., Zaiane, O.

(2022). Mvs-gcn: A prior brain structure learning-

guided multi-view graph convolution network for

autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Computers in

Biology and Medicine 142, 105239.

Williams, J., Scott, F., Stott, C., Allison, C., Bolton, P.,

Baron-Cohen, S., & Brayne, C. (2005). The CAST

(childhood asperger syndrome test) test accuracy.

Autism, 9(1), 45-68.

Wloka, C., Kotseruba, I., Tsotsos, J.K. (2017). Saccade

sequence prediction: Beyond static saliency maps.

arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.10959 .

Wu, C., Liaqat, S., Helvaci, H., Chcung, S.c.S., Chuah,

C.N., Ozonof, S., Young, G. (2021). Machine learning

based autism spectrum disorder detectionfrom videos,

in: 2020 IEEE International Conference on E-health

Networking, Application & Services (HEALTHCOM),

IEEE. pp. 1–6.

Yang, M., Zhong, Q., Chen, L., Huang, F., Lei, B. (2019).

Attention based semi-supervised dictionary learning for

diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. In 2019 IEEE

International Conference on Multimedia & Expo

Workshops (ICMEW) (pp. 7-12).

Zhang, B., Zhou, L., Song, S., Chen, L., Jiang, Z., Zhang,

J., 2020. Image captioning in chinese and its application

for children with autism spectrum disorder, in:

Proceedings of the 2020 12th International Conference

on Machine Learning and Computing, pp. 426–432

Zhao, Z., Zhang, X., Li, W., Hu, X., Qu, X., Cao, X., ... &

Lu, J. (2019). Applying machine learning to identify

autism with restricted kinematic features. Ieee Access,

7, 157614-157622.

Zunino, A., Morerio, P., Cavallo, A., Ansuini, C., Podda, J.,

Battaglia, F., Veneselli, E., Becchio, C., Murino, V.,

2018. Video gesture analysis for autism spectrum

disorder detection, in: 2018 24th international

conference on pattern recognition (ICPR), IEEE. pp.

3421–3426.

ICAART 2025 - 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

860