LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia

Giulia Region

Maria Teresa Chiaravalloti

1 a

, Grazia Serratore

1 b

, Fabio Del Ben

2 c

and Agostino Steffan

2 d

1

Institute of Informatics and Telematics, National Research Council, Rende (CS), Italy

2

CRO Aviano National Cancer Institute IRCCS, Aviano (PN), Italy

Keywords: LOINC, Mapping, Coding System, EHR, Semantic Interoperability.

Abstract: Interoperability in healthcare requires accurate data exchange and interpretation across systems, making

standard terminologies essential for achieving semantic interoperability. This paper presents the approach

adopted by the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region in Italy to implement LOINC, the most widely used standardized

coding system for laboratory tests, into the electronic Laboratory Reports of five hospitals. Mapping was

conducted manually by physicians using RELMA, supported by training and guidance from LOINC Italy

experts. The validation process involved a dual-review procedure to ensure semantic accuracy but also to face

issues, such as implicit or incorrect information in local catalogues and the complexity of some specialties.

Collaboration among clinical staff, LOINC experts, and IT professionals proved essential in overcoming these

issues. As a result, over 7,000 local tests were mapped to LOINC, and 675 new codes for unrepresented

concepts were requested, thus creating a regional LOINC knowledge base. This experience highlights the

importance of training, support, and integrated management in adopting LOINC, as these elements are crucial

for a standardization process that enhances data traceability, minimizes errors, and supports semantic

interoperability. Additionally, this experience could be an example for other healthcare systems aiming to

standardize laboratory tests and achieve meaningful data exchange.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interoperability is defined as the ability of different

information and communications technology systems

and software applications to communicate, exchange

data consistently and reuse the information that has

been exchanged. In the clinical context,

interoperability enables the correct interpretation of

data across systems, allowing healthcare

professionals, patients, and other actors to understand

and act on health-related information and knowledge,

even across linguistic and cultural barriers (European

Commission: Directorate-General for the Information

Society and Media, 2009; Iroju et al., 2013).

Clinical data interoperability is a non-trivial issue

as it consists of technical, technological and semantic

interoperability. It is not sufficient to have an

information system or to adopt shared

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4695-2026

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9481-2213

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1880-0669

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6320-3054

communication protocols, but it is necessary that the

meaning of what is exchanged is not ambiguous so

that it can be understood and above all reused. This

translates into a single word: semantic

interoperability. To this aim, the implementation of

standardized terminologies is critical for effective

knowledge management in healthcare domain.

The use of specialized vocabularies and

terminologies addresses the challenges posed by the

lexical complexity and the high level of specificity of

the “medical jargon”(Gotlieb et al., 2022). Medical

standardized terminologies not only facilitate the

seamless sharing of information among different

healthcare institutions, but also ensure that intended

meanings are preserved throughout the entire clinical

workflow, eliminating ambiguity, controlling

synonyms or equivalents, and establishing explicit

semantic relationships. These systems serve as

Chiaravalloti, M. T., Serratore, G., Del Ben, F. and Steffan, A.

LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region.

DOI: 10.5220/0013380800003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 959-967

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

959

semantic roadmap, providing a shared framework for

both information specialists and users to navigate and

interpret data consistently (Tudhope et al., 2006). The

increasingly extensive use of Electronic Health

Record (EHR) systems requires full semantic

interoperability in order to achieve and pursue the

objective of a comprehensive and reliable record of

an individual’s health history (Aminpour et al., 2014).

In Italy, the Fascicolo Sanitario Elettronico (FSE),

which is the conceptual equivalent of the EHR, was

enacted with the Legislative Decree No. 179/2012. It

is based on a national federated and interoperable

technological infrastructure, which supports patient’s

access to healthcare services throughout the country,

by facilitating the exchange of clinical documents and

data among healthcare providers and patients.

Subsequently, the Prime Minister Decree No.

178/2015 regulated further aspects of the FSE, such

as the data structure of some types of clinical

documents. It then raised the question regarding the

use of classification and coding systems to

standardize and represent health and social-health

data in the clinical documents of the FSE, in order to

ensure, eventually recurring to transcoding, semantic

interoperability at regional, national and international

level. Specifically, the Technical Specifications

attached to the Decree No. 178/2015 indicate the

coding systems to be used within the FSE (Cardillo et

al., 2016), including LOINC (Logical Observation

Identifiers Names and Codes) for laboratory tests

encoding into the Laboratory Report document type.

LOINC is a clinical terminology and the first

universal pre-coordinated code system for laboratory

test names, measurements, and observations (Forrey et

al., 1996). LOINC has been developed by the

Regenstrief Institute (RI) as an open standard and made

available at no cost worldwide. In addition to the

LOINC database, the RI also develops and distributes

a mapping tool called the Regenstrief LOINC Mapping

Assistant (RELMA). This tool facilitates research

through the LOINC database and assists during the

mapping operations between local tests and LOINC

codes. Today LOINC is increasingly widespread all

over the world, de facto becoming the reference

standard for these medical concepts. It is currently used

in more than 196 countries and translated into 15

languages and 20 linguistic variants (consult

https://loinc.org/international/ for continuous updates

on these numbers).

To address the local peculiarities of different

countries, LOINC International has recognized a

network of national partners around the world

(Vreeman et al., 2012). As the LOINC purpose is to

be integrated with local systems and not to substitute

them, it was necessary to collaborate with local

partners responsible for the translation of the standard

and its implementation in their respective national

contexts. Over time, central coordination has revealed

essential for having a common reference point to

address questions, support users, maintain

relationships with governmental bodies and third

parties, keep updated the standard and consider

international updates and challenges in the domain.

This role in Italy is played by the Institute of

Informatics and Telematics of the National Research

Council (IIT-CNR), which established the LOINC

Italy working group, recognized as the official partner

for Italy through a Memorandum of Understanding

signed with the RI in 2014.

LOINC Italy’s activities include biannual updates

to the Italian translation of the LOINC database,

translation of the LOINC Users’ Guide into Italian,

development of tutorials, provision of training

courses, and mapping validation services.

Additionally, an online helpdesk is offered on LOINC

Italy website (www.loinc.it) for information requests

and inquiries, along with the management of new

LOINC codes submissions as needed.

This paper aims to present the approach chosen by

the Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region for the

implementation of LOINC codes into the electronic

Laboratory Reports and, specifically, the mapping

process underway in five large hospitals in the

Region, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of

this experience and drawing lessons from it to

systematize this practice.

2 LOINC MAPPING

Standardizing laboratory test requires using unique

identifiers for each concept and clinical investigation

to ensure consistent information exchange among

laboratories. For effective semantic interoperability,

each laboratory test needs to have a distinct

representation of its specificities. Mapping local

laboratory catalogues to LOINC deals with finding

semantic equivalence of the clinical meaning of each

test and assigning to it a unique code. The structure of

each LOINC code is composed of six fundamental

axes, which represent the pieces of information

needed to detail the performed test with high level of

granularity and specificity.

Nonetheless, mapping local terminologies to

LOINC presents significant challenges, because local

test names are idiosyncratic, often full of acronyms

and abbreviations, and not always explicit with all the

information necessary to uniquely identify the test.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

960

This makes them understandable within the

laboratory or hospital that created them but

ambiguous outside them. The name alone is not

sufficient to fully understand the examination

performed, as information such as the execution

method and the reporting unit of measurement are

essential to distinguish its clinical meaning from

others that may appear similar. At the same time, not

everything labeled in a different way necessarily

corresponds to substantively different tests. For

example, the concept “level of glycosylated

haemoglobin in blood” might appear as “HbA1C” in

some systems, while others might refer to it as

“Haemoglobin A1C” or “Glycohemoglobin”

(Parcero et al., 2013). Therefore, making all the

characteristics of a test explicit helps to quickly

identify the correct LOINC code to map.

Additionally, this reduce misinterpretations that can

impact also the laboratory workflow, from the pre-

analytical phase, through the analytical phase, to the

post-analytical phase (Yusof & Arifin, 2016).

Mapping local catalogues to LOINC helps to reduce

these errors because of the need to remove ambiguity

and provide a clear and consistent way to identify

laboratory tests.

Implementing a robust LOINC mapping requires

substantial planning, focused execution, and ongoing

maintenance to keep it updated with the biannual

releases of the standard. Even if it could not be easy

to introduce in realities with already consolidated

functioning, this standardization process is vital for

enabling meaningful data exchange. By adopting a

common reference terminology, hospitals can ensure

that identical tests are recognized consistently,

reducing errors and misinterpretations, and enhancing

communication among healthcare providers.

After the entry into force of the aforementioned

Prime Minister Decree No. 178/2015, there have been

several regional initiatives and those of individual

hospital structures that have chosen different

approaches to the implementation of LOINC in

Laboratory Reports, requesting or not the support of

LOINC Italy. Even if this initiative aims to facilitate

interoperability, improve patient care, and streamline

data exchange among the laboratories, the lack of

national coordination on the use of coding systems in

clinical documents has caused fragmentation in the

development and implementation of solutions that

ensure efficient management of these systems.

The Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region decided to

approach the mapping process starting from the

laboratories of five large hospitals: CRO Aviano

National Cancer Institute IRCCS of Aviano (PN), the

Burlo children’s hospital of Trieste, and the three-city

hospital of Pordenone (ASFO), Udine (ASUFC) and

Trieste (ASUGI). The work was coordinated by the

in-house company, named Insiel, which manages all

the health informatics process of the Region. The

“mapping team” was composed by informaticians,

MDs from CRO, and LOINC Italia experts. This has

allowed different professionals gathered around the

same table, who have contributed their expertise and

their point of view to achieving a complex objective,

in which the cooperation of IT, medical and specialist

skills on the standard is essential to achieve an

effective and efficient result. Preliminary meetings

were held to analyze the situation and plan the work

phases, as well as numerous meetings to monitor the

progress of the activities.

Despite laboratories working with the same

Laboratory Information System (LIS), they don’t

share the same tests catalogue. This means that

laboratories could perform the same test but call it

differently. Since carrying out a preliminary

reconciliation of the local catalogues was deemed

inconvenient for several reasons, the consequent

decision was to map each hospital’s catalogue to

LOINC, although aware that this would have

necessarily implied the duplication of mapping

efforts on some tests. On the other hand, as a long-

term objective, this approach would have allowed us

to align hospitals’ catalogues by reconciling multiple

names for the same test and allowing to differentiate

identical names that actually conceal clinically

different tests in practice.

Considering the tests catalogues of the five

mentioned hospitals, the total amount of tests to map to

LOINC was 10,619. In accordance with Insiel, we

decided to consider single tests only, and to postpone

the panel’s mapping. In LOINC a panel is a common

name for groups of single tests that are usually ordered

and/or reported together. In Italy it is also called

multiple or battery. It could be more challenging

because mapping a panel code means there must be

matching in their respective child elements.

3 METHODS

The methodology defined for the mapping process

involved several structured phases aimed at ensuring

full semantic correspondence between local tests and

LOINC codes and an effective validation process.

In January 2023, LOINC Italy experts delivered a

comprehensive six-hour webinar to the MDs from the

five involved laboratories, focusing on LOINC,

RELMA and the mapping process. The education

session was followed by a training session aimed to

LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region

961

familiarize laboratory staff with the LOINC coding

system. After that, from February to June 2023,

LOINC Italy experts provided dedicated mapping

assistance on-site at each laboratory. This phase was

crucial in facilitating hands-on support as laboratory

MDs began to implement the mapping process.

Throughout the training process, experts from

LOINC Italy collaborated with laboratory teams to

address any challenges and provide guidance tailored

to their specific contexts and needs. The local

laboratory catalogues were divided according to the

different clinical specialties so the mapping could

have been performed by the MD competent for the

specific sector. This is a very important aspect, as

local test catalogues contain a lot of implicit

information, and sometimes even the information

present is not always correct. This makes it clear that

mapping is not purely an IT matter, as specific

domain expertise is required. RELMA was used as a

tool to support the mapping of local laboratory

catalogues to LOINC.

Starting from July 2023, the laboratories have sent

their locally mapped test catalogues to LOINC Italy,

and the experts have started the third phase of the

activity, which is the validation of the mappings. This

phase includes a dual review process: at first, LOINC

Italy experts verify the mappings based on the

information in the local catalogues. When there are

questionable mappings, they highlight the test in red

and indicate the reason for not validating it. If there

are tests that cannot be mapped because there is no

LOINC code that represents them in a semantically

equivalent way, they submit a request for the creation

of a new LOINC code to LOINC International;

subsequently, mapping MDs are involved for a direct

discussion on questionable mapping cases in order to

find together the right LOINC code or to model a new

code submission. The involvement of clinical domain

experts ensures that the terminology used aligns with

medical practices and ensure that the test performed

is correctly and semantically identified. On the other

hand, LOINC Italy experts are responsible for

verifying that there is conceptual correspondence

between source and target codes and that the

modelling of requests for new codes should be done

according to the formalisms of the standard.

Once the mappings have been validated, it was

then possible to compare them through the chosen

LOINC code to detect any inconsistencies.

At the conclusion of this experience, it was

considered essential to gather feedback from the

clinical users involved in the mapping process. To this

end, one of the participating physicians was asked to

evaluate the experience with the RELMA software and

to provide his insights into the application of the

LOINC standard. This included identifying any

challenges encountered, suggesting areas for

improvement, and highlighting potential benefits.

Additionally, the physician was invited to offer his

perspective as a clinical expert on the

representativeness of LOINC codes across different

laboratory specialties, as well as his thoughts on

potential future applications of the standard and how

the results achieved in this work could be expanded

and reused.

4 RESULTS

The total amount of tests mapped to LOINC is

10,619: 1,013 are from CRO; 2,615 are from ASFO;

3,670 are from ASUFC; 1,693 are from ASUGI, and

1,628 are from Burlo children hospital. The first three

have already completed mapping the tests from their

local catalogues to LOINC, while for the remaining

two, the work is still in progress. Below the results of

the mappings realized by CRO, ASFO, and ASUFC

are presented, in particular describing percentages of

correct mappings, submissions to LOINC for

requesting new codes, and tests identified as non-

mappable because they are either obsolete or only

used for internal calculations and therefore not

reportable into the Laboratory Reports.

CRO mapped 1,013 test codes, belonging to

clinical pathology, clinical biochemistry and clinical

and experimental oncohematology. The mapping was

performed by 1 MD, who collected the necessary

information from his colleagues. For 865 of the tests, it

was possible to identify an existing LOINC code, even

after several clarification meetings between LOINC

Italia experts and the MD. The tests for which it was

not possible to identify an existing LOINC code

amounted to 94. LOINC Italy started the submission

process to request the creation of new LOINC codes to

semantically represent them. This process has a median

processing time of approximately 45 days. The created

terms are then published in the subsequent LOINC

release; however, once developed, they can be viewed

on the pre-release term webpage

(https://loinc.org/prerelease/). Furthermore, the

mapping process enabled the MD to identify

inconsistencies in the catalogue, consisting of 5 tests

non-mappable because they are either not

representative of unique results or used for internal

calculations that do not generate reportable outcomes,

and 54 tests that are no longer performed. So mapping

was also the chance to clean up the local catalogue.

Figure 1 shows the percentage distribution of

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

962

mappings completed by CRO across the described

categories.

Figure 1: The percentage distribution of mappings

completed by CRO according to the described categories.

In the ASFO hospital the mapping process

covered a total of 2,615 test codes. The local

catalogue was divided among 4 MDs, according to

the laboratory specialties of their specific expertise.

The tests belong to the following sectors: allergy,

autoimmunity, bacteriology, biochemistry,

hematology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, HLA,

injury markers, nephrology, POCT, serology,

toxicology, and virology. Overall, the tests mapped to

a LOINC code amount to 2,113; those for which a

submission process has been initiated to request the

creation of a specific LOINC code are 228; 3 have

been classified as non-mappable for the same reasons

stated for the CRO; while 43 refers to tests no longer

performed. Figure 2 shows the percentage

distribution of mappings completed by ASFO across

the categories described.

Figure 2: The percentage distribution of mappings

completed by ASFO according to the described categories.

ASUFC mapped a total of 3,670 codes from

multiple laboratory sectors, such as allergy,

chemistry, autoimmunity, molecular biology,

coagulation, electrophoresis, hematology,

toxicology, gastroenterology, inhibition,

cerebrospinal fluid, cardiac markers, injury markers,

microbiology, hormones, POCT, urine,

uroporphyrins, and virology. The mapping was

performed by 2 MDs, who gathered necessary

information from other laboratory specialties’ MDs.

Of them, 3,347 tests were mapped to an existing

LOINC code; 283 were formally modeled to request

a new LOINC code; 9 are non-mappable codes and

31 no longer realized. Figure 3 shows the percentage

distribution of mappings completed by ASUFC

across the categories described.

Figure 3: The percentage distribution of mappings

completed by ASUFC according to the described

categories.

4.1 Mapping Peculiarities

In this paragraph, we would like to present some

peculiarities observed during the validation of

mappings. First and foremost, it is important to

specify that the effort required to verify the

correctness of the semantic association between the

source code and the target code is not uniform across

all laboratory specialties. There are, in fact, highly

structured and consolidated sectors, either because

they consist of common and recently defined tests,

such as clinical chemistry, or because they are

internally standardized, such as allergology. On the

other hand, there are specialties characterized by

continuous and rapid evolution, where new tests are

frequently formalized, such as genetics, as well as

sectors with recognized intrinsic complexity, such as

microbiology.

Mapped

90%

Submissions

8%

No more realized

2%

ASFO

Total number of tests performed: 2,653

Mapped

87%

Submissions

12%

No more realized

1%

ASUFC

Total number of tests performed: 3,670

Mapped

87%

Submissions

8%

Issues

0%

No more realized

5%

CRO OF AVIANO (PN)

Total number of tests performed: 1,013

LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region

963

In Allergology, the use of Allergen International

Codes as synonyms for the Latin name of the allergen

reported in the LOINC component helps quickly

identify the correct code to map. Nonetheless, even if

international codes are used to identify allergens, it

was necessary to pay close attention to the test

description. For example, the sole label "sunflower"

in the tests “w204 sunflower serum” and “k84

sunflower serum” is not sufficient to distinguish

between tests on pollen or seeds. However, thanks to

the presence of the international codes w204 and k84,

it was possible to assign the correct LOINC code to

each test. Always verifying the correct semantic

interpretation of the test remains crucial to identifying

the most accurate LOINC code. For instance, in the

case of the local test “t45 North American elm serum”

the international code was misleading because it

corresponds to another species of elm, namely Ulmus

Crassifolia. In this case, it was necessary to consult

the competent physician to clarify whether the

international code or the allergen name had been

incorrectly indicated.

In multiple cases we found idiosyncratic local test

names to describe substantially the same test. For

example, the LOINC code 1756-6 Albumin in

CSF/Albumin in Serum or Plasma was assigned to

both the tests named “Barrier Permeability of CSF”

and “Albumin Quotient of CSF”. This is actually the

reason why going to international standards such as

LOINC is so crucial, and it shows how the correct

interpretation of the test semantics is the only way to

identify the most accurate LOINC code. In other

cases, the level of granularity required by LOINC in

the test description, compared to the lack of

descriptive detail in local test catalogues, makes the

mapping validation difficult, as much of the

information is implicit. This often leads also the

physician to map to a more general LOINC code,

even though a more specific one would exist.

Representativeness and granularity issues emerged

mainly for the System axis of virology and

bacteriology tests. For example, the tendency is to use

LOINC codes with System Respiratory system

specimen.lower even if specifying it in Bronchial or

BAL would be possible. In the case of the ASFO

hospital, 41 new LOINC codes with BAL in the

System axis were requested. It was necessary to

ensure an accurate representation of the test

performed. The guiding principle is to always request

new codes if they need to disambiguate and uniquely

identify a test with a greater level of detail.

4.2 New LOINC Codes Submissions

The validation of the mappings realized by the five

hospitals inevitably required requesting the LOINC

Committee to create new LOINC codes for concepts

that were not represented by the existing ones. These

are not always tests recently introduced in the

scientific reference domain; sometimes, they are

requests to narrow the scope of an existing code,

while other times, they are tests specific to a context

different from the North American operational

setting. New LOINC code submissions require a

thorough understanding of the standard's formalism,

as the local test must be "translated" into the six

fundamental LOINC axes, potentially providing

supporting documentation necessary to better

understand what is effectively tested. For this reason,

the submission process is always carried out by

LOINC Italy.

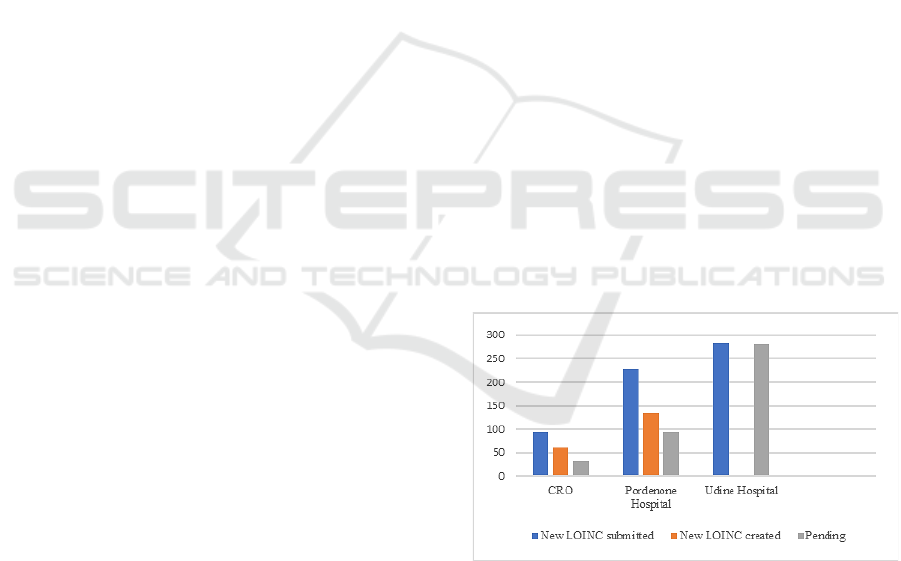

The chart in Figure 4 shows the distribution of

submissions across the CRO, ASFO, and ASUFC

hospitals, for a total of 605 submissions, specifying

those that have already led to the creation of new

LOINC codes (194 out of 605) and those that are still

under review of the LOINC content developers (411

out of 605). The process of creating a new LOINC

code does not stop at the submission, as interactions

with LOINC content developers are often necessary

to precisely identify the clinical meaning of the test

and the semantics to be conveyed through the six

LOINC axes.

Figure 4: New LOINC codes submissions in the CRO,

ASFO and ASUFC hospitals.

Regarding the laboratory specialties for which the

highest number of new codes have been requested,

also considering the observations presented in the

previous paragraph, it is not surprising that the

highest number of new LOINC codes submissions

came from virology and bacteriology, respectively

with 83 and 137 submissions.

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

964

4.3 User Experience

Since we believe that user experience is not a

marginal aspect in the implementation of the LOINC

standard, we asked one of the doctors who actively

participated in the mappings to share his impressions

regarding this activity. He started considering the

challenges posed by the complex and often non-

intuitive structure of the LOINC lexicon but

recognizing that before engaging in any meaningful

mapping task, it is firstly necessary that users

familiarize themselves with the six fundamental

LOINC axes, which serve as the foundation for

understanding the LOINC coding structure. Without

this knowledge, navigating the code system becomes

significantly more difficult, making the mapping

process less effective and efficient. About RELMA

he highlights that it has its own complexity because

of its relatively unfamiliar user interface, although

acknowledging that uploading local databases,

mapping, and exporting results is relatively

straightforward. Challenges lie in mastering the

technical language, understanding the user interface,

and filtering algorithms used by the software.

According to his mapping experience, finding the

semantically correspondent LOINC code depends

heavily on the precision of the search queries. If user

does not get any result, criteria used to filter results in

the “search limits” should be considered as they can

drastically alter the outcomes. This highlights the

importance of a deeper understanding of search

algorithms, a skill set not typically possessed by

medical professionals. As a result, non-technical

users may struggle to achieve the most accurate

mappings without additional training or support. The

high level of granularity in the description of tests

often multiplies the descriptive strings, and therefore,

even when the user performs a search using a single

term and expects a direct result, he/she has to deal

with multiple strings. In these cases, users have to

consider factors such as the ranking of results or the

number of institutions that have chosen a particular

code, opting for what appears to be the most

commonly accepted option. This, however, does not

eliminate the need for LOINC expert validation,

particularly in areas where there is a high degree of

ambiguity. Furthermore, users operating in

unfamiliar domains are often required to consult with

domain experts. This adds both time and complexity

to the task, increasing the potential for human error.

However, he is keen to point out that there are not

only negative aspects and that in fact once users have

mastered these technical aspects, the mapping process

tends to progress smoothly and efficiently. As

familiarity with the LOINC terminology and the

RELMA software grows, the system reveals its

strengths, particularly in its ability to filter results

effectively based on well-constructed queries.

Additionally, the use of standard units of

measurement significantly aids in narrowing down

the search results, ensuring greater and faster

accuracy in the mapping process. This functionality

proves particularly valuable in more established

domains, where consistency in test specifications

allows for quicker and more reliable mappings.

About representativeness, he noticed that LOINC

offers a robust and well-structured framework for

mature fields such as clinical chemistry, while newer

areas like molecular diagnostics are not yet as well-

represented. In these fields, LOINC codes may be

missing or lack the granularity required for detailed

mapping, indicating that the code system has not fully

caught up with advancements in these scientific areas

yet.

In conclusion, he thinks that LOINC holds

considerable promises for facilitating cross-national

interpretation of laboratory results, especially as the

number of mapped local catalogues increases. In the

recently launched European Health Data Space

LOINC could be instrumental in harmonizing inter-

laboratory data across borders, enhancing the

interoperability of health data. Moreover, LOINC

codes can contribute to the development of artificial

intelligence (AI) and machine learning models by

providing a standardized framework for similar tests,

thus bypassing the need for manual annotation and

transcoding. This still relies on the availability of tests

correctly mapped to LOINC through human effort or

at least validated by a human expert. However, the

main critical challenge he foresees might stem from

the lack of specificity regarding the method, as it is

the only axis with optional specification. This, in fact,

could make tests based on different methodologies

appear equivalent. This could introduce significant

variability, potentially skewing AI models.

5 DISCUSSIONS

Programming and implementing the mapping of

laboratory tests from three hospitals in the Friuli

Venezia Giulia region to the LOINC standard codes

enabled the analyses described in the previous

paragraph but also allowed for some reflections on

the mapping work in general. The mapping of local

laboratory catalogues to LOINC is an onerous but

essential process for achieving standardization.

Despite its complexity, efficient planning and

LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region

965

programming can significantly reduce the workload,

ensuring that resources are utilized effectively. It is

crucial to place the right competencies in the right

place at the right time, relying on both domain experts

and LOINC specialists to ensure accurate mappings.

Anticipating the most frequently asked question

from doctors, we always recommend paying attention

to “false friend mappings”, that is the risk of relying

on mappings performed by other laboratories without

carefully reviewing all the descriptive parameters of

the tests before fully adopting their mappings. Tests

that may appear similar in name can differ in context

or clinical specificity and should therefore be mapped

differently. Conversely, not everything labeled

differently necessarily represents fundamentally

different tests. Explicitly stating the values

corresponding to the six fundamental LOINC axes is

the only way to uniquely identify a test.

As a result of what has been explained so far

emerges that it is not feasible to adopt a systematic

method for mapping the local catalogues of different

hospitals to LOINC. A deep understanding of the

information being represented at a semantic level is

essential and, even when two tests appear similar,

careful consideration is needed to distinguish

between them. Additionally, it is not only the naming

of the tests that matters, but also the way the results

are reported. This includes whether the findings are

presented as a laboratory report in natural language or

as evidence based on a specific scale. The way the

tests are documented significantly influences the

choice of the correct LOINC code. Therefore, it is not

possible to apply a uniform method across all

hospitals, as factors such as the form of reporting and

the specific context of each test must be taken into

account when selecting the appropriate LOINC code.

Additionally, if the search for a LOINC code to

map does not yield any results, one should not

immediately resort to requesting the creation of a new

code through submission, especially when dealing

with well-known tests. Often, the appropriate LOINC

code already exists and simply needs careful

identification, for example trying to search with

synonyms or to better focus on the core of the analyte.

Finally, conducting a reverse check of the

mappings at the end of the work is essential. This step

helps in identifying potential errors, such as incorrect

mappings, overlaps between local codes, and

duplications. By implementing this review, the

overall accuracy and consistency of the mapping are

greatly improved. The Friuli Venezia Giulia’s in-

house company was thus able to achieve a general

reorganization of the catalogues of the hospitals

involved, ensuring consistency, particularly in the

two (CRO and ASFO) that share the same test

catalogue. Additionally, it was possible to identify

codes that appeared to represent single tests but

produced in the Laboratory report a series of results

corresponding to multiple observable values, thus

effectively functioning as panel codes.

Finally, it was possible to draft a sort of ranking

of mapping based on difficulty, identifying the

specialties from which it would be advisable to start,

as they are simpler, e.g. allergology because of the

use of Allergen international codes to quickly identify

the right LOINC component to map to; clinical

chemistry is also among the sectors that can be easily

mapped, as the tests have been consolidated for a long

time and are well-structured in the values of the six

fundamental LOINC axes.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper describes the approach chosen by the

Friuli Venezia Giulia Region in Italy to map

laboratory catalogues of five big hospitals to LOINC.

The mapping was manually performed by medical

doctors using RELMA. Overall, over 7,000 local tests

have been mapped to LOINC and the creation of 675

new LOINC codes was requested to represent

concepts not included in the standard. Of these, 194

have already been created and are part of the official

LOINC releases. Thus, a sort of regional LOINC

knowledge base has been created.

Mapping local terms to a standardized vocabulary

is not only a matter of interoperable informative

systems, but it requires a deep knowledge of both the

source and target terminology structures, i.e. the

organization of tests in the local catalogue, which

usually reflects not only a scientific criterion but also

a functional one, and the structuring of a coding

standard such as LOINC. It is a demanding task the

first time, but it becomes easy to maintain afterward,

and the advantages it offers in terms of data

traceability and semantic interoperability are

countless. In our work, it was necessary to find

solutions to the multiple issues encountered during

the mapping and it was possible to address them

through a continuous collaboration among the clinical

staff, the LOINC experts and the informaticians

involved in the activity. The high percentages of

correct mappings and the low percentages of not

identified matches demonstrate that training activities

and mapping support play a fundamental role in

understanding the right way to approach this

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

966

standard. An integrated management of a medical

terminology cannot be able to leave all those aspects

out of consideration, as they all contribute to make

effective and efficient the use of a standardized

system.

All the experiences and specific cases

encountered so far will serve in the future as a

valuable knowledge base for improvements and

efficiencies of the mapping process, potentially

streamlining and accelerating the mapping process

itself and enabling work in an AI-driven environment.

Future work prospects include the need to

complete the validation of mappings carried out by

the two remaining hospitals out of the five (ASUGI

and Burlo Children’s Hospital), covering a total of

3,321 local tests; finalize all pending submissions of

new LOINC terms; and, most importantly, in

collaboration with all stakeholders define

maintenance policy for the mappings performed and

establish procedures for mapping new tests that will

be introduced in the catalogues of the five hospitals

involved.

REFERENCES

Aminpour, F., Sadoughi, F., & Ahamdi, M. (2014).

Utilization of open source electronic health record

around the world: A systematic review. Journal of

Research in Medical Sciences: The Official Journal of

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 19(1), 57–64.

Cardillo, E., Chiaravalloti, M. T., & Pasceri, E. (2016).

Healthcare Terminology Management and Integration

in Italy: Where we are and What we need for Semantic

Interoperability. European Journal for Biomedical

Informatics, 12(01).

https://doi.org/10.24105/ejbi.2016.12.1.14

European Commission: Directorate-General for the

Information Society and Media. (2009). Semantic

interoperability for better health and safer healthcare:

Deployment and research roadmap for Europe.

Publications Office of the European Union.

https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2759/38514

Forrey, A. W., McDonald, C. J., DeMoor, G., Huff, S. M.,

Leavelle, D., Leland, D., Fiers, T., Charles, L., Griffin,

B., Stalling, F., Tullis, A., Hutchins, K., & Baenziger,

J. (1996). Logical observation identifier names and

codes (LOINC) database: A public use set of codes and

names for electronic reporting of clinical laboratory test

results. Clinical Chemistry, 42(1), 81–90.

https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/42.1.81

Gotlieb, R., Praska, C., Hendrickson, M. A., Marmet, J.,

Charpentier, V., Hause, E., Allen, K. A., Lunos, S., &

Pitt, M. B. (2022). Accuracy in Patient Understanding

of Common Medical Phrases. JAMA Network Open,

5(11).

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.42972

Iroju, O., Soriyan, A., Gambo, I., & Olaleke, J. (2013).

Interoperability in Healthcare: Benefits, Challenges

and Resolutions. 3(1).

Parcero, E., Maldonado, J. A., Marco, L., Robles, M.,

Bérez, V., Más, T., & Rodríguez, M. (2013). Automatic

Mapping tool of local laboratory terminologies to

LOINC. Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International

Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems, 409–

412. https://doi.org/10.1109/CBMS.2013.6627828

Tudhope, D., Koch, T., & Heery, R. (2006). Terminology

Services and Technology.

Vreeman, D. J., Chiaravalloti, M. T., Hook, J., &

McDonald, C. J. (2012). Enabling international

adoption of LOINC through translation. Journal of

Biomedical Informatics, 45(4), 667–673.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2012.01.005

Yusof, M. M., & Arifin, A. (2016). Towards an evaluation

framework for Laboratory Information Systems.

Journal of Infection and Public Health, 9(6), 766–773.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2016.08.014

LOINC Mapping Experiences in Italy: The Case of Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region

967