Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights

from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets

Nhung H. Hoang

1 a

and Zilu Liang

1,2 b

1

Ubiquitous and Personal Computing Lab, Kyoto University of Advanced Science (KUAS), Kyoto, Japan

2

Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

{2023md05, liang.zilu}@kuas.ac.jp

Keywords:

Sleep Apnea, AHI, Contrast Set Mining, Longitudinal Data, SHHS.

Abstract:

Sleep apnea remains a key area of sleep research, with the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) widely used to

assess its severity. This study evaluated whether AHI is truly the best indicator of sleep apnea and identified

its limitations. Using the Sleep Heart Health Study and Wisconsin Sleep Cohort datasets, which provide large,

longitudinal data, we also explored survey data on demographics, physiology, and daily behaviors—often

overlooked in polysomnography-based studies. The results indicate that AHI may be a good indicator for

mild or moderate sleep apnea, but not necessarily for normal or severe cases. We highlight some trends that

can be seen from longitudinal data. Additionally, using contrast set mining method, we identified key risk

factors for cardiovascular disease, including age, snoring, and smoking behavior. These results underscore

the importance of considering AHI’s limitations and incorporating additional factors for more accurate sleep

apnea diagnosis and risk assessment.

1 INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) typ-

ically relies on calculating the Apnea-Hypopnea In-

dex (AHI) from a single night of sleep measurement,

which quantifies the number of apneas and hypopneas

per hour of sleep. This index serves as a key metric

for assessing the severity of OSA, with higher AHI

values indicating more severe forms of the disorder.

However, current approach uses only one night of

data presents several challenges. The ”first-night ef-

fect,” where participants experience unnatural sleep

due to the study environment and measurement sen-

sors, may not accurately reflect their typical sleep pat-

terns (Byun et al., 2019). Moreover, a single night’s

data cannot capture the long-term health implications

of sleep, as fluctuations in sleep quality often mani-

fest over extended periods rather than as short-term

changes. Therefore, relying solely on a single record-

ing and summarizing it into a singular metric like

the AHI risks oversimplifying the complex and rich

data available, potentially under-representing the true

severity and nuances of OSA.

Correct labels play a very important role in super-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5805-2087

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2328-5016

vised learning model. Most publications accept AHI

as the best available tool so far. Consistent correla-

tions between the AHI and clinical outcomes have es-

tablished a strong foundation for the use of AHI in

characterizing sleep apnea. However, night-to-night

variability in AHI is seen in mild and moderate sleep

apnea subjects (Bittencourt et al., 2001), (Levy et al.,

2023). While it seems intuitive that the diagnostic

threshold should be adjusted, the values of 5 and 15

events per hour have persistently remained as stan-

dard cut-off points. (Rapoport, 2016) and (Punjabi,

2016) argued the pros and cons of AHI. Employing a

single scale to represent datasets exceeding 1 GB in-

troduces specific limitations. Although apneic events

lasting longer than 30 seconds and SpO

2

desaturation

deeper than 4% are more impactful on mortality in

sleep apnea, the AHI does not account for event du-

ration or desaturation depth, assigning equal weight

to all events (Soori et al., 2022). The distribution of

apneic events is also crucial, as it indicates whether

sleep disruption occurred consistently throughout the

night or was concentrated in a short period.

To the best of our knowledge, there is a significant

gap in understanding the longitudinal impact of OSA.

This study aims to address the following problems:

• Evaluate the reliability of the AHI as a definitive

metric for determining the severity of obstructive

976

Hoang, N. H. and Liang, Z.

Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets.

DOI: 10.5220/0013385500003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 976-983

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

sleep apnea.

• Assessing the associations between sleep apnea

severity as defined by AHI and the cardiovascu-

lar conditions

• Using contrast-set mining to identify influential

factors on long-term health, particularly concern-

ing cardiovascular diseases, in individuals with

and without sleep disorders.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Datasets

In this study, we analysed two publicly available

datasets: the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS)

(Zhang et al., 2018; Quan et al., 1997) and the Wis-

consin Sleep Cohort (WSC) (Young et al., 2009).

Both datasets provide large sample sizes, which allow

for a more comprehensive analysis.

2.1.1 Sleep Heart Health Study

The SHHS dataset is widely regarded as one of the

most influential resources in sleep apnea research.

It includes data from 5,804 participants, with 4,311

individuals (74.28%) completing a follow-up assess-

ment approximately five years after their initial visit.

The study’s comprehensive nature and longitudinal

design have facilitated in-depth analyses, leading to

significant insights into the long-term health conse-

quences of sleep apnea and related disorders.

2.1.2 Wisconsin Sleep Cohort

This ongoing longitudinal study examines the causes,

outcomes, and natural progression of sleep disorders,

particularly sleep apnea. Although smaller in scope

than the SHHS, this dataset includes 2,570 individual

sleep records. Participants typically engage in up to

four clinic visits, though two participants completed

a fifth visit. In total, 1,123 subjects participated in

the initial visit, 758 (67.50%) returned for the sec-

ond, 566 (50.40%) for the third, 121 (10.77%) for the

fourth, and two subjects for the fifth.

Each visit is separated with intervals typically

ranging from four to six years, as depicted in Figure

1. For participants with multiple visits, the majority

of the data spans eight years or more. This extended

timeline is particularly promising for monitoring the

progression and impact of sleep disorders over time.

Figure 1: The chart illustrates the distribution of time in-

tervals between the first and the last examinations of the

participants in the WSC study.

2.2 Contrast Set Mining

Contrast set mining aims to identify rules that em-

phasize significant differences between groups us-

ing metrics like support, confidence, and lift. The

STUCCO algorithm facilitates analysis by uncover-

ing statistically meaningful contrasts across subpop-

ulations (Bay and Pazzani, 2001; Gamberger and

Lavrac, 2011). The STUCCO algorithm has been

previously applied to uncover hidden correlations be-

tween sleep and glucose (Hoang and Liang, 2023).

Rules in contrast set mining consist of antecedents

(conditions) and a consequent (outcome) in the for-

mat (X

1

AND X

2

) → Y

1

.

If the dataset contains attributes like smoking

habits, BMI, and snoring frequency, the method gen-

erates rules like: (BMI > 25 AND Smokes) → High

Risk of Sleep Apnea. This rule can be interpreted as:

”Subjects who smoke and have a Body Mass Index

(BMI) greater than 25 are more likely to have a higher

risk of sleep apnea.” In general, rules generated by

this method follow the same structure: when the con-

ditions specified on the left-hand side (antecedents)

are met, the probability of the outcome specified

on the right-hand side (consequent) increases. To

maintain interpretability and reduce redundancy, rules

are limited to three antecedents. Valid contrast sets

must meet thresholds of support (≥10%), confidence

(≥75%), and lift (≥2).

2.3 Processing Questionnaires Data

This work does not center on biosignal processing

but instead prioritizes extracting insights from the

questionnaires during the first (SHHS1) and second

(SHHS2) visits. From the 1,896 variables listed in the

”shhs-data-dictionary-0.20.0-variables.csv” file, we

selected variables of interest that reflect daily routines

and well-being, which are listed in Table 1.

Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets

977

Table 1: List of questionnaire information used for contrast set mining.

Left-hand-side features Right-hand-side

features

Physiological Behavioral Medical history Treatment Cardiovascular

diseases

Education level,

marital status,

age, body mass

index, weight,

height, neck

circumference,

cholesterol,

triglycerides,

gender

Smoking status,

number of packs of

cigarettes/years,

number of cigarettes

smoke per day,

alcohol, coffee, tea,

soda, sleep pill,

napping, difficulty

falling asleep, sleep

time on weekdays and

weekends

History of heart

attack, stroke,

hypertension

(HTN), diabetes,

asthma,

loudness of

snoring,

frequency of

snoking, change

of snoring

condition over

time

Any surgery

treatment for

sleep apnea, any

surgery

treatment for

snoring, using

oxygen therapy

during sleep,

using pressure

mask or

mouthpiece

Any cardiovascular

diseae since baseline,

any coronary heart

disease since base

line, number of

angina since baseline,

vital status

2.3.1 Left-Hand-Side Factors

The left-hand-side factors in this analysis represent

potential predictors or contributing factors to the out-

comes observed on the right-hand side. This study

aims to identify specific behaviors that may exac-

erbate the complexity of cardiovascular problems.

The left-hand-side factors are categorized into four

groups: physiological, behavioral, medical history,

and treatment.

2.3.2 Right-Hand-Side Factors

For the right-hand-side, we selected factors related to

cardiovascular diseases, specifically the onset of such

conditions after the first sleep record. Focusing on the

appearance of angina episodes and vital status, which

serve as the primary target outcomes for this study.

However, analyzing and interpreting the result-

ing contrast sets proved challenging due to the large

number of extracted rules. To address this, we im-

plemented post-processing steps to filter out seman-

tically unclear contrast sets, such as those containing

ambiguous terms like ”unknown” or those with insuf-

ficient support. Based on previous research, we set

a threshold of at least 50 subjects or 10% of the sur-

veyed group for a contrast set to be considered valid.

3 RESULTS

After processing the data and retaining individuals

with complete records, we kept 1,938 subjects from

the SHHS dataset and 758 subjects from the WSC

dataset for further analysis. Specifically, SHHS was

used for contrast set mining to identify relationships

Table 2: Clinical standard for converting AHI to sleep ap-

nea severity in adults, with the number of subjects in each

dataset (first measurement).

AHI value Severity SHHS WSC

0-5 Normal 382 350

5-15 Mild 824 214

15-30 Moderate 592 115

>30 Severe 316 79

between behavioral factors and the development of

cardiovascular diseases, while both datasets were an-

alyzed to evaluate the utility of the AHI metric.

3.1 Changes in AHI over Time

While processing the data from SHHS and WSC, it is

easy to recognize the drastic change in AHI between

the first and second visits in SHHS and among visits

in WSC.

3.1.1 Sleep Heart Health Study

After analyzing AHI data from the first and second

visits of the SHHS dataset, which were conducted five

years apart, more than half of the subjects (n=1,061,

54.75%) maintained the same severity level of sleep

apnea. Among the remaining subjects, 474 individu-

als (24.48%) showed a reduction in sleep apnea sever-

ity to a milder level, while 412 individuals (21.25%)

experienced an increase in severity.

We noticed some significant changes in the AHI

values between the two measurements. We have 238

(12.38%) cases ∆AHI ≥20 in which the majority de-

veloped severe apnea. The largest difference observed

was 75.56 in subject 200187, whose AHI increased

from 9.77 in the first measurement to 85.33 in the sec-

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

978

ond measurement. This change reflects a progression

from mild to severe sleep apnea, with the AHI value

nearing three times the lower threshold of the severe

category. Specifically, the average apnea duration in-

creased from an estimated 1–2 minutes per hour (as-

suming each apnea episode lasts at least 10 seconds,

as defined by the AASM) to approximately 14 min-

utes per hour.

It is noteworthy that among all surveyed subjects,

only 22 individuals had an AHI below 1 during the

first measurement, and 38 during the second. This

raises the question: does this imply that almost ev-

eryone experiences at least one apnea event per hour,

or are these events potentially artifacts caused by sig-

nal disturbances during data collection? Addition-

ally, there are individuals with AHI values exceeding

60—38 and 56 participants for the first and second

measurements, respectively, with the highest values

surpassing 90.

Such findings cast doubt on the reliability of AHI

as an accurate metric. Among the recorded apnea

events, how many truly reflect physiological episodes

of sleep apnea, and how many result from measure-

ment noise? Disruptions in the connection between

devices and patients, caused by movement during

sleep, could introduce sudden changes, such as dips

in oxygen saturation levels and could be mistaken as

apnea events.

The instability of AHI as a metric for assessing

sleep apnea severity is even more evident in the WSC

dataset, which includes more measurement points and

a longer experimental timeline.

3.1.2 Wisconsis Sleep Cohort

In the WSC dataset, we focus on individuals whose

AHI deviates by at least 20 units from the median

value during at least one measurement. There are

81 such cases, accounting for 10.69% of the dataset.

These instances likely indicate that the AHI does not

accurately reflect the severity of sleep apnea in one or

more measurements.

For example, subject 11445’s AHI over four vis-

its was reported as 5.95, 11.82, 70.04, and 8.35. The

third visit stands out with a sudden spike to 70, con-

trasting sharply with the other measurements, which

suggest the individual generally has normal health or

mild apnea. Similar patterns are observed in other

cases, such as:

• ID 17286: 2.96 → 42.78 → 14.17

• ID 25122: 19.17 → 81.53 → 2.53

• ID 31546: 6.25 → 50.53 → 17.49

• ID 86874: 1.36 → 33.08 → 1.4 → 1.4

• ...

Subject 23154 exhibited an opposite trend com-

pared to prior examples, with AHI values fluctuat-

ing between 60.66, 23.25, and 63.5 over three vis-

its. While the second visit indicated a great improve-

ment, the third visit showed a return to the initial high

AHI, suggesting the condition remained severe over-

all. Similar trends were observed in other cases:

• ID 38751: 51.64 → 55.64 → 10.16

• ID 72224: 36.68 → 18.31 → 65.58

• ID 78382: 52.24 → 0.88 → 46.91

• ID 74274: 47.41 → 8.03 → 34.67 → 61.45

• ...

The most critical focus of our investigation is on

cases where the AHI has misjudged the severity of

sleep apnea during the first measurement. This is

particularly relevant since many studies rely on the

first AHI measurement as a foundation for develop-

ing machine learning models due to its large sample

size. For example, in the case of subject ID 89915, the

AHI was 49.66 in the first measurement, categorizing

the subject as severe, but subsequent measurements

showed AHI values of 1.29, 2.74, and 1.66, placing

the subject in the healthy range. Conversely, subject

ID 64771 had AHI values of 3.24, 26.03, and 31.54

across three visits, with the AHI increasing in subse-

quent measurements. Some other examples that we

found in the dataset:

• ID 71343: 81.76 → 3.06 → 3.3 → 3.3

• ID 43143: 34.37 → 1.92 → 1.44

• ID 42371: 0.37 → 22.59 → 20.93

• ...

These discrepancies raise a key question: is a sin-

gle AHI value sufficient to assess the severity of sleep

apnea? Moreover, when used as ground truth in ma-

chine learning models, how accurate can these models

be, given the potential inaccuracies of AHI as a met-

ric?

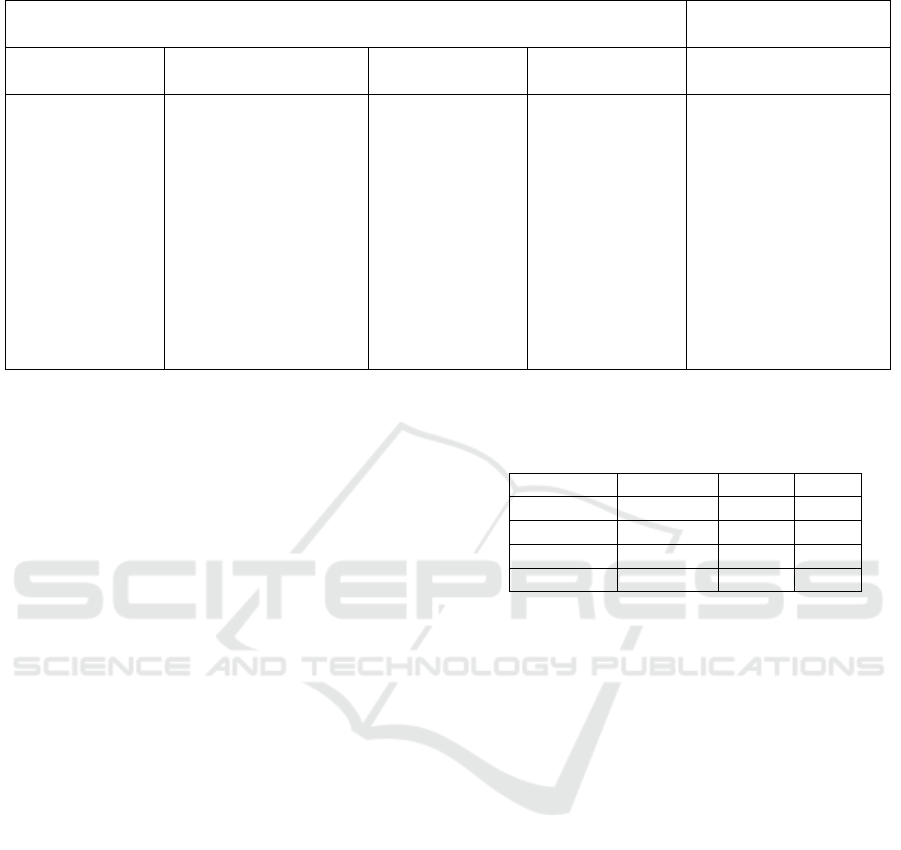

3.2 Cardiovascular Health

Consequence

Table 3 presents the occurrence of cardiovascular dis-

eases (CVDs) following the first visit of SHHS partic-

ipants. The data indicate a clear trend: the prevalence

of CVDs increases over time. At baseline, 1910 par-

ticipants were free of congestive heart failure (CHF),

while 28 had experienced at least one episode. After

baseline, the number of participants with at least one

CHF increased to 203. Similar patterns are observed

Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets

979

for myocardial infarctions (MIs), heart attack-related

procedures, and strokes.

Further analysis of the dataset based on vital sta-

tus reveals that, five years after the initial visit, 270

participants had passed away. Among these, 170 in-

dividuals experienced at least one fatal cardiovascular

event, such as coronary heart disease, heart attack, or

stroke. None of these health issues were reported in

participants who remained alive. Examining the pro-

gression of cardiovascular diseases, Figure 2, the vari-

able prev chf in the deceased group increased signif-

icantly, from 4.81% before the first visit to 38.52%.

Similarly, prev mi and mi show that the prevalence

of MIs rose from 10.37% to 21.11%, whereas no

changes were observed in the surviving group.

3.3 Relationship Between the Change of

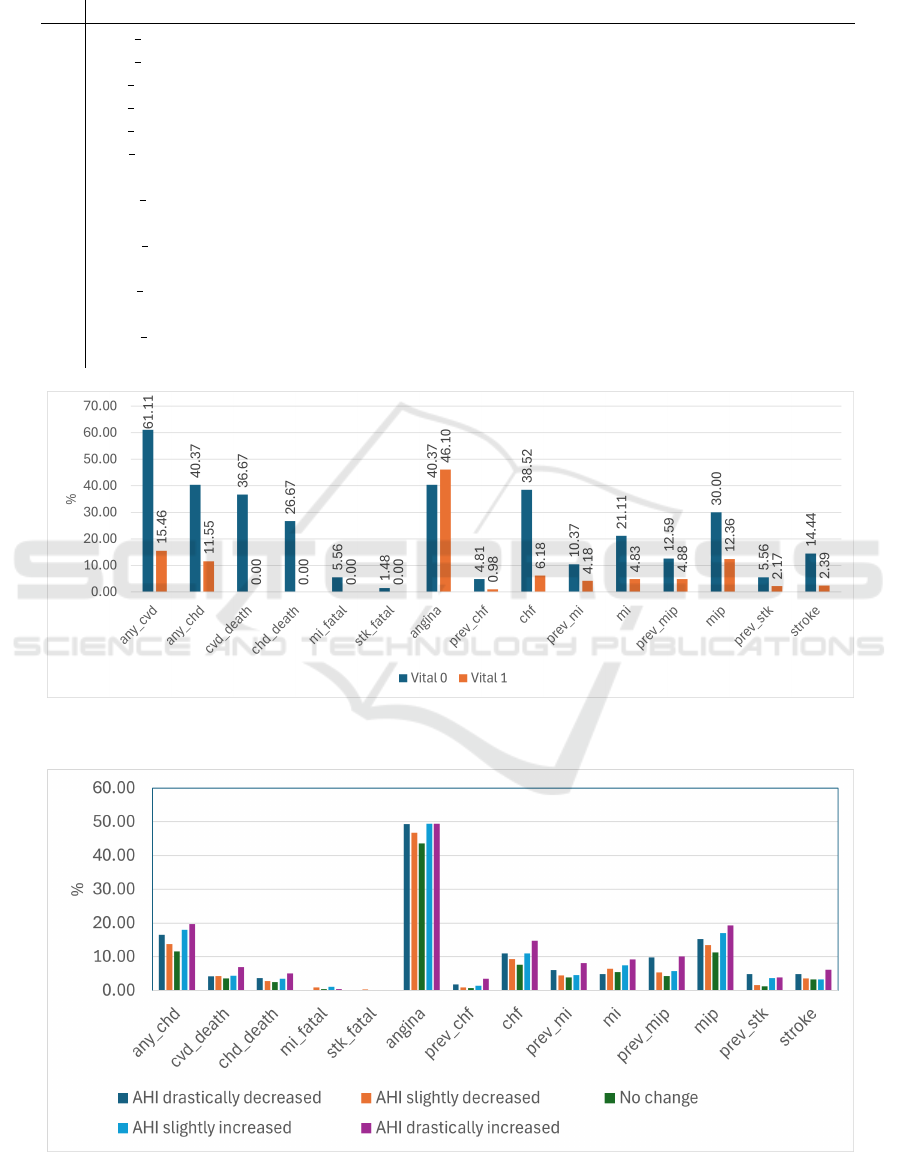

AHI and Cardiovascular Condition

To make it easy understanding, and it is also necessary

to discretize data for the contrast set mining method,

we suggest the cut-off values as follows, based on the

AHI standard and our observation:

∆AHI ∈

(∞, −15) Drastic decrease

(−15, −5) Slight decrease

(−5, 5) No change

(5, 15) Slight increase

(15, ∞) Drastic increase

It is well recognized that sleep apnea, through its

direct effects on breathing, can have significant impli-

cations for cardiovascular health. Interestingly, most

participants who experienced more than three angina

episodes over time also showed an increase in AHI

(15 out of 21). Among these individuals, all had at

least mild sleep apnea except one. Subject 202626,

despite experiencing the highest number of angina

episodes, did not have sleep apnea and maintained a

consistently low AHI over five years.

Furthermore, a reduction in AHI did not con-

sistently correlate with improved cardiovascular out-

comes. The prevalence of heart problems or the need

for heart surgeries in the group with a ”drastic AHI

decrease” was comparable to that in the group with a

”drastic AHI increase”. AHI alone can not fully cap-

ture the complex interplay between sleep apnea and

cardiovascular health.

One interesting information is a high proportion

of subjects in all groups experienced angina episodes,

with nearly half reporting at least one episode dur-

ing the five years of observation. Angina, character-

ized by chest pain or discomfort caused by insufficient

oxygen supply to the heart muscle, is plausibly linked

to the consequences of sleep apnea, where partial or

complete airway obstruction occurs. This raises the

question of whether the progression of sleep apnea

may exacerbate this condition?

3.4 Impact of Life Factors

The focus was placed on the occurrence of angina

episodes and vital status. By interpreting the con-

trast sets, we generated some hypotheses regarding

the usefulness of AHI. For better presentation, we

listed the most interesting rules in Table 4 and made

the others available to access in the following link:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/

1gUqNFhcYkVbgUXohBoYlZkdIfyV-UFpA?

usp=drive link

3.4.1 Impact on Angina Episodes

Major factors influencing the presence of angina in-

clude age, snoring, and neck circumference. Individ-

uals aged 60 and above are at a notably higher risk.

Frequent or loud snoring further increases the likeli-

hood of developing angina. Similarly, a neck circum-

ference exceeding 39 cm in males or 35 cm in females

is strongly associated with elevated risk.

Other influential factors include smoking, BMI,

difficulty maintaining sleep after interruptions, fre-

quently napping, intermediate triglyceride levels, and

cholesterol levels categorized as either optimal or

high. While these factors appeared less frequently in

the contrast sets, they are still important in identifying

angina risk.

An unexpected finding is the correlation between

educational attainment and angina risk. Specifically,

individuals with 16–20 years of education (typically

high school through university levels) appeared fre-

quently in the contrast sets. This suggests a hypothe-

sis that individuals with relatively high educational at-

tainment might engage in unhealthy lifestyle choices

that negatively impact their long-term health.

In terms of obstructive sleep apnea severity, con-

trast set mining revealed significant associations be-

tween mild and moderate apnea groups and angina.

Interestingly, neither the normal nor severe apnea

groups appeared in the contrast sets, regardless of

whether the right-hand side was defined as the pres-

ence or absence of angina. This is surprising given

the relatively even distribution of OSA severity levels

in the dataset.

The absence of the severe group as a significant

factor for predicting angina might support our hypoth-

esis. Specifically, an AHI greater than 30 may not

be a reliable indicator for the development of angina.

This could be attributed to the potential inaccuracy of

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

980

Table 3: Survey statistics on cardiovascular diseases. For rows 1-6, 0: no, 1: yes. Starting from row 7, the unit of measurement

is the number of events, where 0: does not occur, 1: occurs once, and >1: occurs more than once.

Label Description 0 1 >1

1 any cvd Any cardiovascular disease since baseline? 1515 423

2 any chd Any coronary heart disease since baseline? 1635 303

3 cvd death Fatal cardiovascular disease since baseline? 1850 88

4 chd death Fatal coronary heart disease since baseline? 1875 63

5 mi fatal Fatal heart attack since baseline? 1926 12

6 stk fatal Fatal stroke since baseline? 1934 4

7 angina Num of angina episodes since baseline 1033 868 37

8 prev chf Num of congestive heart failure episodes prior to baseline 1910 24 4

9 chf Num of congestive heart failures episodes since to baseline 1735 109 94

10 prev mi Num of myocardial infarctions prior to baseline 1844 84 10

11 mi Num of myocardial infarctions since baseline 1801 122 15

12 prev mip Num of procedures related to heart attack prior to baseline 1827 87 24

13 mip Num of procedures related to heart attack since baseline 1648 180 110

14 prev stk Num of strokes prior to baseline 1888 46 4

15 stroke Num of strokes since baseline 1867 49 22

Figure 2: The chart illustrates the percentage of individuals with at least one cardiovascular event across different vital status

groups (0: dead, 1: alive).

Figure 3: The chart illustrates the percentage of individuals with at least one cardiovascular event with groups of AHI changing

over time.

Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets

981

Table 4: Interesting rules generated by contrast set mining method.

Subgroups Target Lift Support (%) Confidence (%)

1 Napping for more than 2 days/week AND → Deceased group 2.93 10.08 82.43

Have hypertention AND

Smoke more than 5 packs/year

2 Have hypertention AND → Deceased group 2.88 10.53 85.29

Age 70-80 AND Smoking

3 Napping for more than 2 days/week AND → Deceased group 2.86 10.51 76.71

Lose weight AND

Smoke more than 5 cigaretters/day

4 Age 40-50 AND → No angina 2.03 17.65 80.77

No napping

5 Age 40-50 AND → No angina 2.02 12.35 79.73

Female AND

Not using aspirin

6 Age 60-70 AND → Have angina 2.53 11.59 86.11

Snore louder after 5 years AND

Sometimes has problem falling asleep

7 More than 20 years of education AND → Have angina 2.38 12.56 89.06

Snoring

8 Age 60-70 AND → Have angina 2.26 14.40 87.65

Snore as loud as mumbling or talking AND

Neck circumference outside window

very high AHI values, which are more likely to result

from signal disturbances. These disturbances could

be caused by the subject’s movement or device mal-

functions during the measurement process.

The method identified only three contrast sets in-

dicating the absence of angina. These sets highlight

groups defined by younger age (40–50 years), infre-

quent or no napping, non-use of aspirin, and female

subjects.

3.4.2 Impact on Vital Status

For contrast sets related to vital status, it is reasonable

that age emerges as the most dominant factor, particu-

larly in the 70–80 age group. Hypertension, observed

both at the first measurement and in follow-up after

five years, ranks as the second most significant factor.

Once again, smoking behavior plays a crucial role in

indicating deteriorating health or even mortality. Nap-

ping also appears more frequently, which is reason-

able since the effects of sleep apnea can increase day-

time sleepiness, prompting the need for naps.

A final interesting pattern is weight loss among the

deceased group, contrasting with the angina-related

contrast sets where obesity was prominent. While

weight gain contributes to cardiovascular disease pro-

gression, specifically angina, weight loss is com-

monly observed as the body weakens in later stages.

4 DISCUSSIONS

Our analysis of longitudinal data provides evidence

that AHI is not entirely accurate. This problem has

been debated in many of the existing studies (Punjabi,

2016; Kulkas et al., 2013; Soori et al., 2022). The

findings of this study further support the hypotheses

proposed in earlier research. Errors can arise due to

the natural variability of sleep and the complex nature

of related disorders, which remain poorly understood.

This issue is clearly reflected in specific cases from

both datasets, as detailed in our results section.

To enhance the accuracy of OSA diagnosis, it is

ideal to employ multiple sleep records collected over

time and consider the effect of disturbed signal. Al-

though there is a foundation for this assumption, it

remains challenging to establish that all body move-

ments are associated with errors in scoring apnea

events. Introducing a penalty index for signals with

high noise ratios may be a potential approach; how-

ever, this requires a comprehensive evaluation of sig-

nal quality through further study. Moreover, the in-

herent inaccuracies of AHI should be accounted for to

avoid developing machine learning models that over-

fit the data by focusing solely on achieving the high-

est accuracy. (Kulkas et al., 2013) questioned the

reliance on the AHI as a sole indicator of sleep apnea

severity and proposed four new parameters to better

characterize the condition. Their study, with a median

HEALTHINF 2025 - 18th International Conference on Health Informatics

982

follow-up of 183 months, examined the correlation

of these parameters with patient mortality and found

them to be more accurate in predicting mortality out-

comes. If validated, these parameters would neces-

sitate a reassessment of existing sleep apnea scor-

ing systems. However, a limitation of the study is

the wide interval between measurements; incorporat-

ing daily or weekly sleep records, achievable through

wearable technology, would enhance the robustness

of the findings.

The notable achievement of contrast set mining

in our analysis lies in its ability to condense vast

datasets and highlight dominant risk factors in rela-

tion to the selected outcomes. This methodological

strength enables researchers to identify and priori-

tize meaningful patterns that might otherwise be over-

looked, thus forming a foundation for more targeted

and hypothesis-driven investigations.

A significant limitation of contrast set mining is

the difficulty in interpreting the rules without prior

knowledge. The process of post-processing to select

important rules also depends on the researcher’s ex-

pertise. In this study, we utilized a wealth of infor-

mation from the questionnaire; however, due to the

complexity of the responses, some data were not ad-

equately captured in the contrast sets. This challenge

highlights the need for careful selection and interpre-

tation of the data to ensure meaningful insights are

derived.

5 CONCLUSION

This study highlights key insights into the limitations

of using the AHI as the ground truth for classify-

ing sleep apnea severity and its relationship to car-

diovascular health. We demonstrate that relying on a

single-night sleep record can be inaccurate, and longi-

tudinal tracking with multiple sleep records provides

greater reliability. Our findings show no clear rela-

tionship between changes in apnea severity and the

development of cardiovascular diseases. Addition-

ally, through contrast set mining, we identified key

factors linked to adverse heart health trends, including

age, snoring frequency, and smoking habits. These

discoveries provide hypotheses for future studies to

better understand cardiovascular risk factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored by Japan Society for the

Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career

Scientists (Grant Number 21K17670).

REFERENCES

Bay, S. D. and Pazzani, M. J. (2001). Detecting group

differences: Mining contrast sets. Data mining and

knowledge discovery, 5:213–246.

Bittencourt, L. R. A., Suchecki, D., Tufik, S., Peres, C.,

Togeiro, S. M., Bagnato, M. D. C., and Nery, L. E.

(2001). The variability of the apnoea–hypopnoea in-

dex. Journal of sleep research, 10(3):245–251.

Byun, J.-H., Kim, K. T., Moon, H.-j., Motamedi, G. K.,

and Cho, Y. W. (2019). The first night effect dur-

ing polysomnography, and patients’ estimates of sleep

quality. Psychiatry research, 274:27–29.

Gamberger, D. and Lavrac, N. (2011). Expert-guided sub-

group discovery: Methodology and application. arXiv

e-prints, pages arXiv–1106.

Hoang, N. and Liang, Z. (2023). Contrast set mining

for actionable insights into associations between sleep

and glucose in a normoglycemic population. In Pro-

ceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference

on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technolo-

gies (BIOSTEC 2023), pages 522–529. INSTICC,

SciTePress.

Kulkas, A., Tiihonen, P., Julkunen, P., Mervaala, E., and

T

¨

oyr

¨

as, J. (2013). Novel parameters indicate signif-

icant differences in severity of obstructive sleep ap-

nea with patients having similar apnea–hypopnea in-

dex. Medical & biological engineering & computing,

51:697–708.

Levy, J.,

´

Alvarez, D., Del Campo, F., and Behar, J. A.

(2023). Deep learning for obstructive sleep apnea

diagnosis based on single channel oximetry. Nature

Communications, 14(1):4881.

Punjabi, N. M. (2016). Counterpoint: is the apnea-

hypopnea index the best way to quantify the severity

of sleep-disordered breathing? no. Chest, 149(1):16–

19.

Quan, S. F., Howard, B. V., Iber, C., Kiley, J. P., Nieto,

F. J., O’Connor, G. T., Rapoport, D. M., Redline, S.,

Robbins, J., Samet, J. M., et al. (1997). The sleep heart

health study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep,

20(12):1077–1085.

Rapoport, D. M. (2016). Point: Is the apnea-hypopnea

index the best way to quantify the severity of sleep-

disordered breathing? yes. Chest, 149(1):14–16.

Soori, R., Baikunje, N., D’sa, I., Bhushan, N., Nagab-

hushana, B., and Hosmane, G. B. (2022). Pitfalls of

ahi system of severity grading in obstructive sleep ap-

noea. Sleep Science, 15(S 01):285–288.

Young, T., Palta, M., Dempsey, J., Peppard, P. E., Nieto,

F. J., and Hla, K. M. (2009). Burden of sleep apnea:

rationale, design, and major findings of the wisconsin

sleep cohort study. WMJ: official publication of the

State Medical Society of Wisconsin, 108(5):246.

Zhang, G.-Q., Cui, L., Mueller, R., Tao, S., Kim, M.,

Rueschman, M., Mariani, S., Mobley, D., and Red-

line, S. (2018). The national sleep research resource:

towards a sleep data commons. Journal of the Amer-

ican Medical Informatics Association, 25(10):1351–

1358.

Reconsidering AHI as an Indicator of Sleep Apnea Severity: Insights from Mining Large, Longitudinal Sleep Datasets

983