Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children:

HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC)

Aleenah Khan

a

and Hassan Foroosh

Department of Computer Science, University of Central Florida, Orlando, U.S.A.

{al450857, hassan.foroosh}@ucf.edu

Keywords:

Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD, Self-Stimulatory Behaviors, Stimming, Self-Injurious Behaviors,

Stereotypical Behaviors, Self-Harm.

Abstract:

Self-Stimulatory behaviors, or stimming is quite common in Autism and can begin as early as infancy. Autistic

infants may show early signs of stimming through repetitive movements such as hand flapping, rocking, or

head banging. These stereotypical behaviors help self-regulation and are generally not harmful unless they

pose a safety risk (e.g., head banging) or significantly interfere with daily activities. In such cases, the parent

or caregiver must immediately intervene to ensure the safety of the child. To foster a safe environment for

autistic children, we introduce a novel problem of identifying potentially harmful self-stimulatory behaviors

to alert the parent / caregiver. To pave the way for research, we consolidated a video-based dataset “Har-

mAlert4AutisticChildren” which categorizes autism-related stimming behaviors into two categories: helpful

and harmful. We utilize existing publicly available video datasets that focus on a different problem of self-

stimulatory behavior classification in autism. The curation process is based on a systematic review of the

literature of clinical research studies that analyze the impacts of various self-stimulatory behaviors in autistic

children. In addition to introducing a new research problem and a new dataset, we also provide baseline re-

sults using the Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP) model. The dataset and code are available on

GitHub: https://github.com/AleenahK/HarmAlert4AutisticChildren-HA4AC.

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the National Institute of Mental Health,

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neu-

rological and developmental disorder that can cause

significant social and behavioral challenges. Diagnos-

tic criteria for ASD involve the evaluation of social-

communication skills, including poor eye contact, dif-

ficulty maintaining conversations, and lack of devel-

opmentally appropriate peer relationships, in addi-

tion to the presence of restricted or repetitive behav-

iors such as stereotyped motor movements, hypo- or

hyper-sensitivities, and unusual interests (American

Psychiatric Association et al., 2013). It is known as

a spectrum disorder because there is a wide variation

in the type and severity of symptoms people experi-

ence.

Restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs) are

a core characteristic of ASD and are also referred

to as ’stereotyped behaviors’, ’stereotypy’, ’self-

stimulatory behaviors’ or ’stimming’ in clinical lit-

erature. We will use these terms interchangeably

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2807-1551

throughout the remainder of the article. These be-

haviors include a range of actions including but not

limited to hand flapping, head banging, finger tap-

ping, spinning, scratching, clapping, rocking back

and forth, and lining up and flapping objects. It

also includes producing auditory stimuli, such as

whistling, humming, or idiosyncratic speech.

Early research studies declared these stereotypi-

cal behaviors redundant and discussed how these can

negatively impact autistic people by causing myriad

difficulties such as hindrance in learning capabilities

(Koegel and Covert, 1972), and social interactions

(Koegel et al., 1974). It is important to note that

these initial studies were based on very small groups

of autistic children.

Recently, there has been an increase in research

that attempts to shift the focus towards exploring the

experiences of autistic adults. Based on thematic

analysis of qualitative data obtained through question-

naires, interviews, and focus groups of autistic adults,

the researchers aim to understand their experiences

and perceptions of self-stimulatory behaviors. As a

result, it is revealed that self-stimulatory behaviors

986

Khan, A. and Foroosh, H.

Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children: HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC).

DOI: 10.5220/0013389700003912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2025) - Volume 2: VISAPP, pages

986-994

ISBN: 978-989-758-728-3; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

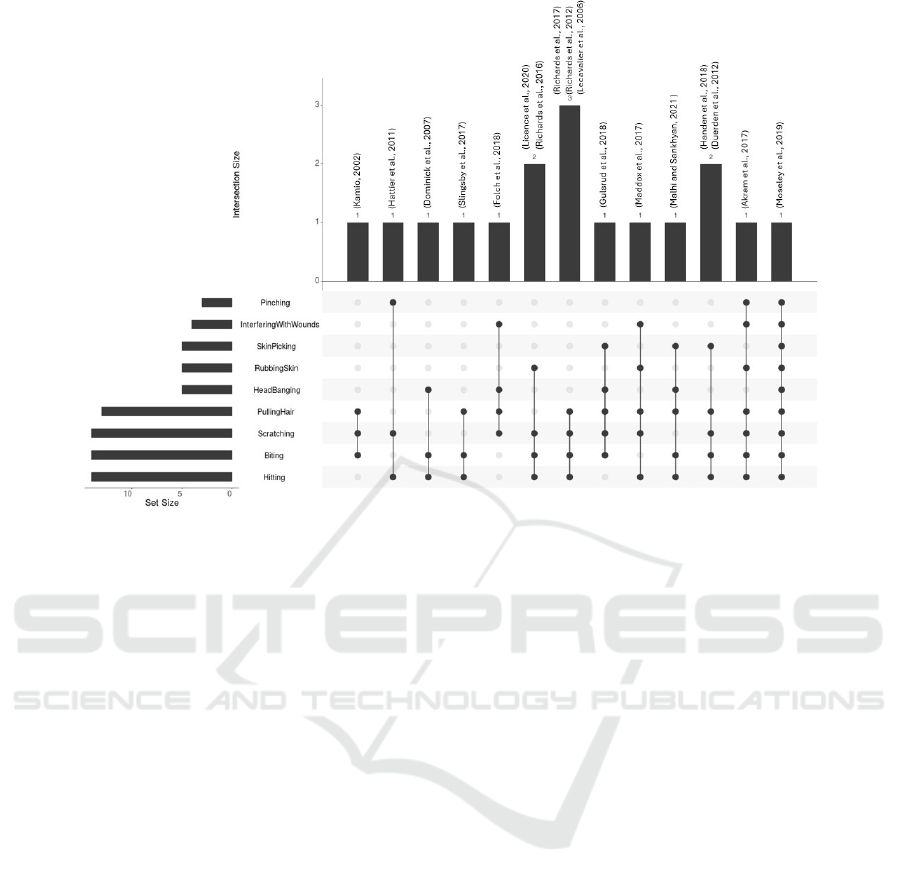

Figure 1: Summarizing Clinical Studies on ASD-related Self-Injurious Self-Stimulatory Behaviors.

help regulate intense emotions, dissipate anxiety, and

manage sensory sensitivities, while suppressing these

leads to further stress (Kapp et al., 2019), (Charlton

et al., 2021).

According to the National Autistic Society, self-

stimulatory behaviors are often very helpful and en-

joyable; however, some of these can be self-injurious,

for example, head-banging, scratching, biting, skin

picking, hair pulling, etc.

According to a 2017 study (Guan and Li, 2017)

published in the American Journal of Public Health,

individuals with a diagnosis of autism are at a sub-

stantially heightened risk of death due to injury. Dur-

ing the 16-year study period, about 27.9 % of the

deaths in autistic individuals were attributed to injury

mortality. In addition, deaths due to unintentional

injury in autistic individuals were nearly 3 times as

likely as in the general population especially for chil-

dren under 15 years.

Hence, we conclude that self-stimulatory behav-

iors can be either helpful or harmful. It is crucial

for the parent / caregiver to analyze the situation and

act accordingly. It is very important to provide a

supportive environment to allow autistic people to

freely engage in stimming without having to suppress

it. On the contrary, if the behavior is causing any

kind of harm like self-injurious behaviors, the par-

ent/caregiver should address it with appropriate inter-

ventions.

We realize that ASD not only has significant neg-

ative impacts on a child’s development, but it also af-

fects their family’s social, emotional, and economic

well-being. Providing care and support for autistic

people requires a significant investment of time and

effort. Parents and caregivers frequently report ex-

periencing stress and anxiety related to caring for an

autistic child. (Estes et al., 2013), (Lecavalier et al.,

2006).

In an effort to help autistic people and their fam-

ilies, we propose a new computer vision task with

the objective of developing models that can distin-

guish between helpful and harmful self-stimulatory

behaviors to send alerts for intervention. The very

initial step towards building such an automated sys-

tem is to provide a standard, publicly available, video-

based dataset representing both helpful and poten-

tially harmful behaviors. This research paper focuses

on utilizing existing ASD-related video datasets, orig-

inally formulated for other tasks, to curate a new

dataset.

2 DATASET CURATION

A high-quality video dataset aligned with helpful

and harmful self-stimulatory behaviors is crucial for

building robust automated systems that are capable

of identifying self-injurious behaviors and alerting the

parent or caregiver to intervene and ensure the safety

of autistic children.

Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children: HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC)

987

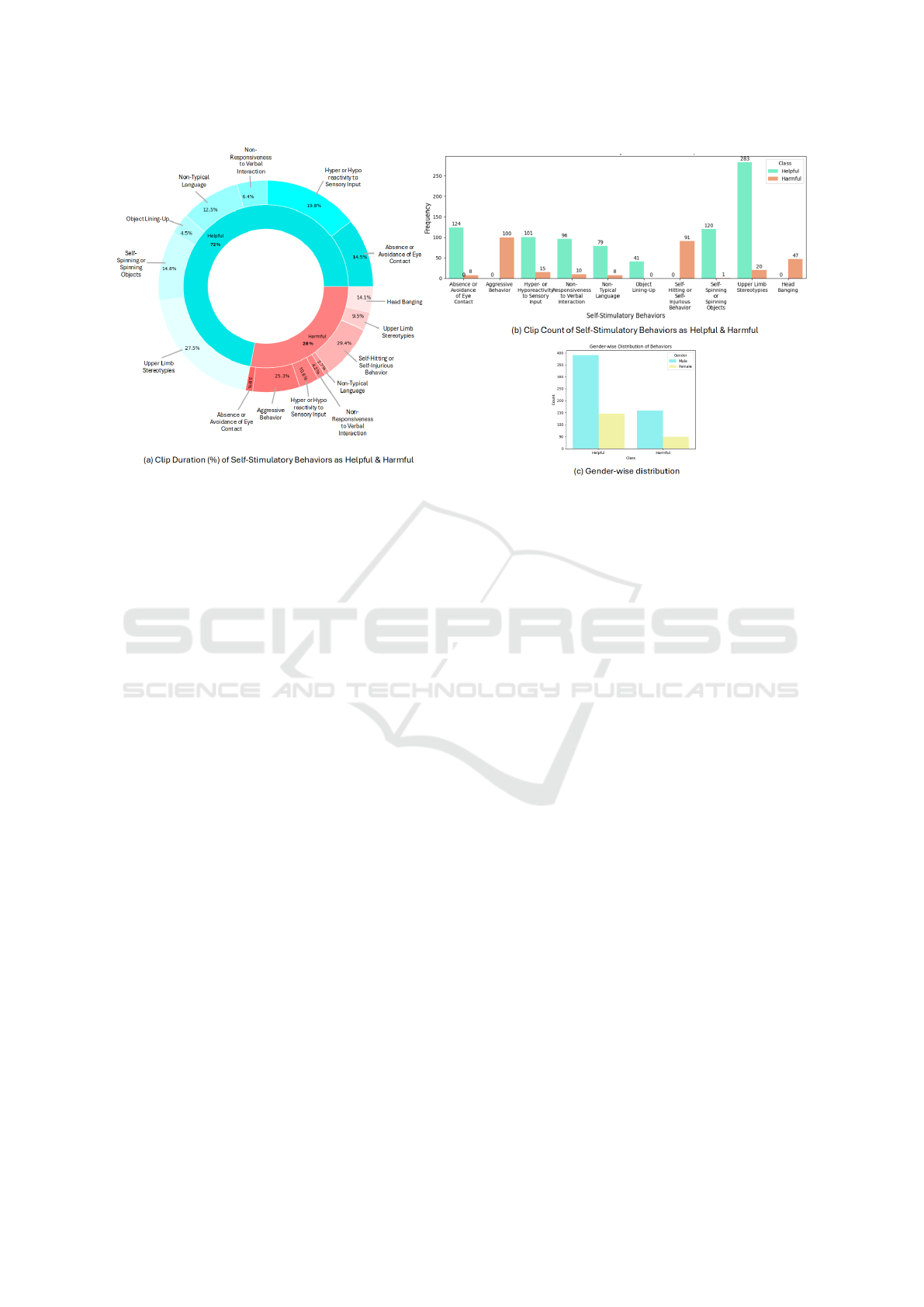

Figure 2: Harm Alert 4 Autistic Children - HA4AC Dataset.

Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, such

a dataset does not exist, and due to ethical concerns,

like identity protection, creating it from scratch is

also challenging. However, the computer vision re-

search community has been working towards building

datasets that represent self-stimulatory behaviors with

the aim of developing diagnostic systems to iden-

tify early signs of autism. Early diagnosis and in-

tervention can significantly improve verbal and non-

verbal communication, learning capabilities, social

reciprocity, and overall well-being of autistic chil-

dren. These datasets have been collected from pub-

licly available videos of autistic people filmed by their

parents or caregivers and shared on social media plat-

forms such as YouTube.

These ASD-related datasets have representations

of different self-stimulatory behaviors, such as, head

banging and hand flapping, however they don’t clas-

sify the nature of the behavior as positive or negative.

We aim to leverage these publicly available datasets

to curate a new dataset by categorizing the available

action classes as either HELPFUL or HARMFUL.

To avoid any kind of personal bias, instead of re-

lying on our instincts, we perform a systematic liter-

ature review of behavioral studies conducted by clin-

ical researchers to analyze both positive and negative

impacts of various self-stimulatory behaviors.

Based on this analysis, we then bifurcate the

self-stimulatory behaviors present in the existing

ASD-related datasets and propose the new ”Har-

mAlert4AutisticChildren” dataset to identify poten-

tially problematic stimming behaviors in autistic chil-

dren.

In the following section, we present a system-

atic review of clinical research studies focused on

autism-related self-stimulatory behaviors to analyze

their positive and negative impact on autistic people

to classify them as helpful or harmful.

2.1 Clinical Studies

To understand the impacts of different self-

stimulatory behaviors, such as, their functions

(e.g. self-regulation, sensory stimulation) or their

consequences (e.g. self-harm), we conduct a sys-

tematic study of existing clinical literature. We

aim to distinguish between helpful or harmless

self-stimulatory behaviors, especially those that can

potentially cause harm by identifying the overlap

between self-stimulatory and self-injurious behaviors

in autistic people.

2.1.1 Search Keywords

We identify four sets of keywords to search for rel-

evant behavioral studies related to autism, namely:

Context, Neutral, Positive, and Negative. Each of

these sets represents field-specific jargon and is listed

as follows.

• Context: self-stimulation, self-stimulatory be-

haviors, stereotypical behaviors, stereotypy, stim-

ming, autism, ASD, fidgeting

• Neutral: statistics, impacts, affects, analysis, in-

sights, prevalence, frequency

• Positive: helpful, benefits, positive, self-soothing,

emotional regulation, healthy, de-stress

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

988

• Negative: risk factors, issues, difficulties, nega-

tive, harm, injury, self-injurious, self-harm, dan-

gerous, aggressive

2.1.2 Search Queries

We formulate search queries using the appropriate

combinations of search keywords mentioned in Sec-

tion 2.1.1. To retrieve relevant articles, we use both

generic and action-specific queries. Action-specific

queries include additional keywords that represent

self-stimulatory behaviors such as ”head banging”

and ”hand flapping”. We provide one example of each

of these categories in neutral, positive, and negative

contexts, respectively.

• Generic Queries

– Impacts of self-stimulatory behaviors in

Autism

– Autistic self-stimulation and emotional regula-

tion

– Self-injurious stereotypical behaviors

• Action-Specific Queries

– Hyper-sensitivities in autistic individuals

– Helpful vocal stims

– Head-banging injuries in autism

2.1.3 Search Results & Analysis

In this section, we discuss the results of our search

and provide analysis that helped us categorize self-

stimulatory behaviors as helpful and harmful. We first

share insights about the helpful stimming behaviors

followed by those that are potentially harmful accord-

ing to evidences from clinical studies.

Studies that highlight the benefits of self-

stimulatory behaviors and advocate for them are

based on first-person accounts of autistic adults.

Autistic children often struggle to communicate and

express their feelings due to the prevalence of non-

verbality and minimum verbality. Due to this reason,

they are also not able to explain the significance of

self-stimulatory behaviors in their life. With the help

of early intervention therapies, autistic children man-

age to gain language abilities later in their life.

Research studies based on first-person accounts of

autistic adults advocate in favor of self-stimulatory

behaviors and describe stimming using words with

deeply positive connotations such as ’calming’, ’com-

forting’, ’soothing’, ’joyful’ and ’enjoyable’. Stim-

ming helps autistic people overcome feelings of ner-

vousness, anxiety, and anger, or express happiness

and excitement (Kapp et al., 2019). It also helps autis-

tic people organize their thoughts, improve focus, and

get rid of excessive energy (Joyce et al., 2017).

We present a summarized list of different motor,

vocal, and visual stereotypes that often help autistic

people based on personal experiences shared through

questionnaires, focus groups, and questionnaires con-

ducted in these behavioral studies.

• Motor Stereotypes: hand flapping, body rock-

ing, pacing back and forth, finger tapping, spin-

ning, twirling pen or jewelry, doodling, jumping

or bouncing

• Vocal Stereotypes: humming, whistling,

echolalia, use of atypical language

• Visual Inspection: aligning objects, spinning ob-

jects

We also share some personal accounts of autis-

tic individuals in their own words which convey their

sentiments in a persuasive way.

• ”People should be allowed to do what they like” -

(Kapp et al., 2019)

• ”Stim your heart out” & ”Syndrome rebel” -

(Stevenson, 2020)

• “It feels like holding back something you need to

say” - (Charlton et al., 2021)

• ”If I don’t Do It, I’m Out of Rhythm and I Can’t

Focus As Well” - (McCormack et al., 2023)

• ”I Wish They’d Just Let Us Be” - (Sagar et al.,

2023)

• ”It Helps Make the Fuzzy Go Away” - (Friedman

et al., 2024)

Next, we discuss clinical studies that report the

prevalence of negative or harmful stereotypical be-

haviors related to autism. Self-harm or self-injurious

behavior (SIB) is a major concern for autistic chil-

dren and adolescents. These behaviors are defined

as non-accidental, non-suicidal, self-inflicted actions

that result in physical injury (Yates, 2004). Examples

of such behaviors include self-biting, self-hitting, hair

pulling, skin picking, scratching, etc. (Furniss and

Biswas, 2012), (Guan and Li, 2017), (Maddox et al.,

2017). We summarize the results of our search for

harmful self-stimulatory behaviors in Figure 1. With

the help of an Upset Plot (Lex et al., 2014), we visu-

alize the intersection of different stereotypical actions

studied in these research studies. The latter half of

the figure represents the occurrences of these behav-

iors in clinical literature (left) and the different combi-

nations studied together (right), while the former half

provides references of these studies. Self-hitting, self-

biting, self-scratching, and pulling hair are the most

reported stimming behaviors with respect to Autism

Spectrum Disorder.

Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children: HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC)

989

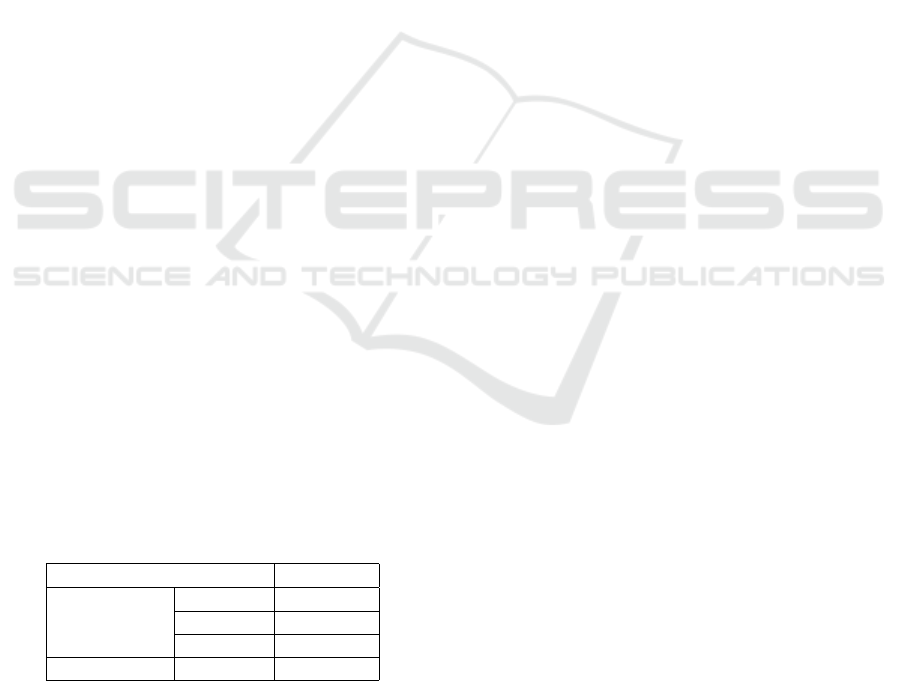

Figure 3: Examples of Helpful & Harmful Self-Stimulatory Behaviors.

Table 1: Comparison of Existing ASD-related Datasets used in the “HarmAlert4Autistic” Dataset.

SSBD ESBD SSBD+ ASBD AV-ASD

Original Size 75 141 61 165 928

Categories 3 4 3 4 10

Self- ArmFlapping ArmFlapping ArmFlapping ArmFlapping AbsenceOrAvoidanceOfEyeContact

Stimulatory HeadBanging HandAction HeadBanging HandAction AggressiveBehavior

Behaviors Spinning HeadBanging Spinning HeadBanging Background

Spinning Spinning HyperOrHyporeactivityToSensoryInput

Non-ResponsivenessToVerbalInteraction

Non-TypicalLanguage

ObjectLining-Up

Self-HittingOrSelf-InjuriousBehavior

Self-SpinningOrSpinningObjects

UpperLimbStereotypies

Annotated Yes No Yes Yes Yes

Source YouTube YouTube YouTube YouTube YouTube

Vimeo Facebook

DailyMotion

Release Year 2013 2021 2023 2023 2024

2.2 Self-Stimulatory Datasets

In this section, we study existing ASD-related video

datasets that have been the focus of the computer vi-

sion research community in the past decade. We dis-

cuss these datasets in chronological order of their ex-

istence. A summarized comparison of these datasets

is presented in Table 1.

2.2.1 Self-Stimulatory Behavior Dataset (SSBD)

The first attempt to create a video dataset for model-

ing self-stimulatory behaviors related to Autism Spec-

trum Disorder was made by (Rajagopalan et al., 2013)

in 2013. The Self-Stimulatory Behavior Dataset

(SSBD) consisted of 75 distinct videos distributed

into three categories: Arm Flapping, Head Banging,

and Spinning. These videos were recorded in natu-

ral settings by parents or caregivers of autistic chil-

dren and were collected from the popular social media

website YouTube.

2.2.2 Expanded Stereotype Behavior Dataset

(ESBD)

In 2021, (Negin et al., 2021) proposed a larger dataset

called the Expanded Stereotype Behavior Dataset

(ESBD). The new dataset consisted of a total of 141

videos, approximately twice the size of the SSBD

dataset. They also added a new class label referred

as ”Hand Action” together with the existing classes,

Arm Flapping, Head Banging, and Spinning. The

problem with the ESBD dataset is that it was not prop-

erly annotated with start time and end time of the

stimming behaviors. We provide proper annotations

for all videos in the ESBD dataset to include them in

our new dataset.

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

990

2.2.3 Updated Self-Stimulatory Behavior

Dataset (SSBD+)

(Wei et al., 2023) made an effort to expand the ex-

isting SSBD dataset by including 12 new videos and

removing 11 noisy videos. Like the SSBD dataset, the

new videos were also added from YouTube. The final

dataset consisted of 61 unique and noise-free videos

spanning the same three categories: Arm Flapping,

Head Banging, and Spinning.

2.2.4 Autism Stimming Behavior Dataset

(ASBD)

Recently, (Ribeiro et al., 2023) combined all the

aforementioned datasets: SSBD, ESBD and Updated

SSBD to create a new consolidated dataset called

the Autism Stimming Behavior Dataset (ASBD). The

final dataset consisted of 165 distinct videos that

spanned four classes. They also provide annotations

for start time and duration of the stimming actions.

2.2.5 Audio-Visual Autism Spectrum Dataset

(AV-ASD)

(Deng et al., 2024) recently introduced a more ex-

tensive audio-visual dataset to stimulate further re-

search for the diagnosis of autism-related behaviors.

Unlike preceding datasets, AV-ASD includes both so-

cial interaction challenges, and restricted and repeti-

tive behaviors (RRBs). The AV-ASD dataset is also

richer in terms of both quality and quantity, having

a much greater number of both categories and sam-

ples. This dataset comprises 928 clips extracted from

569 unique videos distributed in 10 categories. These

video clips include diverse behaviors and environ-

ment settings and are collected from popular social

media platforms YouTube and Facebook. The dataset

provides multiple labels for each video clip consider-

ing the fact that an autistic individual can exhibit mul-

tiple autistic behaviors at the same time. The dataset

also provides precise time-stamp annotations for the

start and end of each autistic behavior.

3 HarmAlert4AutisticChildren

The HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC) dataset is

our effort to consolidate a new dataset using videos

from the five existing datasets discussed in the previ-

ous section. It is the first dataset designed to enable

research towards the development of automated sys-

tems that should be capable to distinguish between

helpful/harmless and harmful self-stimulatory behav-

iors. The proposed dataset consists of a total of

731 video clips extracted from 368 distinct videos

downloaded from various social media apps, such as

YouTube, Facebook, Vimeo and DailyMotion. These

videos are captured in realistic, unbounded scenes and

include diverse behaviors which fall in one of the two

categories: Helpful (527 clips; 10761 s) or Harmful

(204 clips; 3437 s). The shortest clip has a duration

of 2 seconds, while the longest clip is 14 minutes and

48 seconds long. All video clips have carefully as-

signed time stamp annotations representing start time

and end time of the self-stimulatory behavior exhib-

ited in the clip.

Based on the analysis presented in Section 2.1.3

and Figure 1 of this article, we are able to identify

the following self-stimulatory behaviors from exist-

ing datasets as ’Harmful’: Head Banging, Aggres-

sive Behaviors, and Self-Hitting Or Self-Injurious

Behaviors. The rest of the self-stimulatory behav-

iors are considered as ’Helpful’ as they seem to be

harmless considering the literature. However, these

stimming behaviors do not always occur in isolation

and often overlap with each other. Figures 2 (a) and

2 (b) represent the percentage of time duration and

frequency of occurrence of these stereotypical behav-

iors that show their contribution to both Helpful and

Harmful classes, respectively. Figure 2 (c) represents

the gender-wise distribution of the data indicating the

dominance of male autistic children in the dataset.

This disparity aligns with research studies that claim

autism spectrum disorder is more commonly diag-

nosed in males than females. The male-to-female ra-

tio in autism diagnoses is often cited as around 4:1.

According to another research study (Schuck et al.,

2019), females camouflage the symptoms of ASD

more than males potentially contributing to the dif-

ference in prevalence.

Figure 3 presents a set of five samples for each of

the two class categories.

4 EXPERIMENTS

For benchmarking purposes, we evaluate the perfor-

mance of CLIP-based models in zero-shot settings for

our newly curated HA4AL dataset. Below are the ex-

perimental details of the baseline models.

4.1 Contrastive Language-Image

Pretraining (CLIP)

The Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP)

model (Radford et al., 2021) is a multi-modal vi-

sion and language model which maps image and text

pairs to a shared embedding space. CLIP is widely

Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children: HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC)

991

known for its ability to generalize and perform zero-

shot learning effectively. Despite originally being

designed for images, CLIP can be easily adapted to

work with videos. We use the following two strate-

gies to evaluate the CLIP model on our downstream

task.

4.1.1 Vanilla CLIP

The most straightforward approach to adapting the

CLIP model (Radford et al., 2021) for video classifi-

cation is to apply temporal pooling to the embeddings

of individual frames, thus generating a unified repre-

sentation. In our experiments, we used the ViT-B/16,

ViT-B/32, and ViT-L/14 models in zero-shot settings.

4.1.2 Video Fine-Tuned CLIP

The ViFi-CLIP model (Rasheed et al., 2023) em-

ploys video-based fine-tuning of the image-based

CLIP model to bridge the domain gap between im-

ages and videos. The input video frames are first pro-

cessed using the CLIP image encoder to obtain fea-

ture embeddings. These embeddings are then inte-

grated through feature pooling, followed by similar-

ity matching with the corresponding text embeddings.

The ViFi-CLIP ViT-B/32 model used in our experi-

ments is fine-tuned on the Kinetics-400 dataset (Kay

et al., 2017). Kinetics-400 is a human action dataset

with 400 classes and at least 400 video clips per

class covering a wide range of both human-action and

human-human interactions. The fine-tuning process

is performed for 10 epochs, and the resulting model

is evaluated on the downstream HA4AL dataset un-

der zero-shot settings.

4.2 Evaluation Metric

To evaluate the performance of the CLIP-based mod-

els in our downstream task using the HA4AL dataset,

we use accuracy as the evaluation metric.

Table 2: Experimental Results.

Model Accuracy

Vanilla CLIP

ViT-B/16 37.2 %

ViT-B/32 41.9 %

ViT-L/14 56.1 %

ViFi-CLIP ViT-B/32 50.7 %

4.3 Results & Analysis

The zero-shot evaluations of both vanilla CLIP and

ViFi-CLIP on our downstream task show impressive

generalization capability of the CLIP model in Table

2. In case of Vanilla CLIP, the ViT-L/14 model per-

forms better than the other variants ViT-B/16 and ViT-

B/32 with a 56.1 % accuracy. The reason being that

the ViT-L14 model has a larger configuration with

more transformer layers and, therefore, more learn-

able parameters. The ViT-L/14 has a 14x14 patch

size which enables it to capture finer details and in-

creases it’s capacity to learn complex relationships

in the data. To compare Vanilla CLIP with ViFi-

CLIP, we use the same ViT-B/32 configuration. As

expected, ViFi-CLIP outperforms Vanilla CLIP with

an 8.8 % improvement due to the fine-tuning advan-

tage. It is unsurprising that the model with the largest

configuration, ViT-L/14 outperforms the rest.

5 CONCLUSION

In this research paper, we introduce a new computer

vision-based recognition task to identify potentially

harmful and harmless stereotypical behaviors in autis-

tic population. We took the first step towards solv-

ing this problem by proposing a new dataset, the Har-

mAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC) dataset. We per-

form a systematic review of the existing clinical lit-

erature to understand the topography, functions, and

consequences of self-stimulatory behaviors to catego-

rize them as helpful and harmful. By evaluating exist-

ing datasets for self-stimulatory behavior recognition,

we filter positive and negative examples of exhibiting

self-harm and aggression. We also present baseline

results using CLIP-based video classification models

to benchmark future research efforts.

6 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The proposed HA4AC dataset suffers from a class

imbalance problem, with helpful stimming behaviors

constituting 74 % and harmful behaviors compris-

ing only 26 %, at a ratio of 3.55:1. Furthermore,

the HA4AC dataset exhibits gender imbalance, with

the male population comprising 74 % of the data

points and autistic female children underrepresented.

In our future work, we plan to work on this class

imbalance problem and employ state-of-work large-

language models to improve the accuracy on the video

classification task.

REFERENCES

Akram, B., Batool, M., Rafi, Z., and Akram, A. (2017).

Prevalence and predictors of non-suicidal self-injury

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

992

among children with autism spectrum disorder. Pak-

istan Journal of Medical Sciences, 33(5):1225.

American Psychiatric Association, D., American Psychi-

atric Association, D., et al. (2013). Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5, vol-

ume 5. American psychiatric association Washington,

DC.

Charlton, R. A., Entecott, T., Belova, E., and Nwaordu,

G. (2021). “it feels like holding back something you

need to say”: Autistic and non-autistic adults accounts

of sensory experiences and stimming. Research in

Autism Spectrum Disorders, 89:101864.

Deng, S., Kosloski, E. E., Patel, S., Barnett, Z. A., Nan, Y.,

Kaplan, A., Aarukapalli, S., Doan, W. T., Wang, M.,

Singh, H., et al. (2024). Hear me, see me, understand

me: Audio-visual autism behavior recognition. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2406.02554.

Dominick, K. C., Davis, N. O., Lainhart, J., Tager-Flusberg,

H., and Folstein, S. (2007). Atypical behaviors in

children with autism and children with a history of

language impairment. Research in developmental dis-

abilities, 28(2):145–162.

Duerden, E. G., Oatley, H. K., Mak-Fan, K. M., McGrath,

P. A., Taylor, M. J., Szatmari, P., and Roberts, S. W.

(2012). Risk factors associated with self-injurious be-

haviors in children and adolescents with autism spec-

trum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental

disorders, 42:2460–2470.

Estes, A., Olson, E., Sullivan, K., Greenson, J., Winter,

J., Dawson, G., and Munson, J. (2013). Parenting-

related stress and psychological distress in mothers of

toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Brain and

Development, 35(2):133–138.

Folch, A., Cort

´

es, M., Salvador-Carulla, L., Vicens, P.,

Iraz

´

abal, M., Mu

˜

noz, S., Rovira, L., Orejuela, C.,

Haro, J., Vilella, E., et al. (2018). Risk factors and to-

pographies for self-injurious behaviour in a sample of

adults with intellectual developmental disorders. Jour-

nal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(12):1018–

1029.

Friedman, S., Noble, R., Archer, S., Gibson, J., and Hughes,

C. (2024). “it helps make the fuzzy go away”: Autistic

adults’ perspectives on nature’s relationship with well-

being through the life course. Autism in Adulthood,

6(2):192–204.

Furniss, F. and Biswas, A. (2012). Recent research on

aetiology, development and phenomenology of self-

injurious behaviour in people with intellectual disabil-

ities: a systematic review and implications for treat-

ment. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research,

56(5):453–475.

Guan, J. and Li, G. (2017). Injury mortality in individu-

als with autism. American journal of public health,

107(5):791–793.

Gulsrud, A., Lin, C., Park, M., Hellemann, G., and Mc-

Cracken, J. (2018). Self-injurious behaviours in

children and adults with autism spectrum disorder

(asd). Journal of intellectual disability research,

62(12):1030–1042.

Handen, B. L., Mazefsky, C. A., Gabriels, R. L., Peder-

sen, K. A., Wallace, M., and Siegel, M. (2018). Risk

factors for self-injurious behavior in an inpatient psy-

chiatric sample of children with autism spectrum dis-

order: A naturalistic observation study. Journal of

autism and developmental disorders, 48:3678–3688.

Hattier, M. A., Matson, J. L., Belva, B. C., and Horovitz,

M. (2011). The occurrence of challenging behaviours

in children with autism spectrum disorders and atypi-

cal development. Developmental Neurorehabilitation,

14(4):221–229.

Joyce, C., Honey, E., Leekam, S. R., Barrett, S. L., and

Rodgers, J. (2017). Anxiety, intolerance of uncer-

tainty and restricted and repetitive behaviour: Insights

directly from young people with asd. Journal of

Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47:3789–3802.

Kamio, Y. (2002). Self-injurious and aggressive behavior

in adolescents with intellectual disabilities: A com-

parison of adolescents with and without autism. The

Japanese Journal of Special Education, 39(6):143–

154.

Kapp, S. K., Steward, R., Crane, L., Elliott, D., Elph-

ick, C., Pellicano, E., and Russell, G. (2019). ‘peo-

ple should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic

adults’ views and experiences of stimming. Autism,

23(7):1782–1792.

Kay, W., Carreira, J., Simonyan, K., Zhang, B., Hillier, C.,

Vijayanarasimhan, S., Viola, F., Green, T., Back, T.,

Natsev, P., et al. (2017). The kinetics human action

video dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.06950.

Koegel, R. L. and Covert, A. (1972). The relationship

of self-stimulation to learning in autistic children 1.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 5(4):381–387.

Koegel, R. L., Firestone, P. B., Kramme, K. W., and Dunlap,

G. (1974). Increasing spontaneous play by suppress-

ing self-stimulation in autistic children 1. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 7(4):521–528.

Lecavalier, L. (2006). Behavioral and emotional problems

in young people with pervasive developmental disor-

ders: Relative prevalence, effects of subject character-

istics, and empirical classification. Journal of autism

and developmental disorders, 36:1101–1114.

Lecavalier, L., Leone, S., and Wiltz, J. (2006). The impact

of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young

people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of in-

tellectual disability research, 50(3):172–183.

Lex, A., Gehlenborg, N., Strobelt, H., Vuillemot, R., and

Pfister, H. (2014). Upset: visualization of intersecting

sets. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer

graphics, 20(12):1983–1992.

Licence, L., Oliver, C., Moss, J., and Richards, C. (2020).

Prevalence and risk-markers of self-harm in autistic

children and adults. Journal of autism and develop-

mental disorders, 50(10):3561–3574.

Maddox, B. B., Trubanova, A., and White, S. W. (2017).

Untended wounds: Non-suicidal self-injury in adults

with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(4):412–

422.

Malhi, P. and Sankhyan, N. (2021). Intentional self harm

in children with autism. The Indian Journal of Pedi-

atrics, 88:158–160.

Towards Safe Self-Stimulatory Behaviors in Autistic Children: HarmAlert4AutisticChildren (HA4AC)

993

McCormack, L., Wong, S. W., and Campbell, L. E. (2023).

‘if i don’t do it, i’m out of rhythm and i can’t focus

as well’: Positive and negative adult interpretations of

therapies aimed at ‘fixing’their restricted and repeti-

tive behaviours in childhood. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 53(9):3435–3448.

Moseley, R., Gregory, N. J., Smith, P., Allison, C., and

Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). A ‘choice’, an ‘addiction’,

a way ‘out of the lost’: exploring self-injury in autis-

tic people without intellectual disability. Molecular

autism, 10:1–23.

Negin, F., Ozyer, B., Agahian, S., Kacdioglu, S., and Ozyer,

G. T. (2021). Vision-assisted recognition of stereotype

behaviors for early diagnosis of autism spectrum dis-

orders. Neurocomputing, 446:145–155.

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G.,

Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark,

J., et al. (2021). Learning transferable visual models

from natural language supervision. In International

conference on machine learning, pages 8748–8763.

PMLR.

Rajagopalan, S., Dhall, A., and Goecke, R. (2013). Self-

stimulatory behaviours in the wild for autism diagno-

sis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Confer-

ence on Computer Vision Workshops, pages 755–761.

Rasheed, H., Khattak, M. U., Maaz, M., Khan, S., and

Khan, F. S. (2023). Fine-tuned clip models are effi-

cient video learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF

Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recogni-

tion, pages 6545–6554.

Ribeiro, G. O., Grellert, M., and Carvalho, J. T. (2023).

Stimming behavior dataset-unifying stereotype be-

havior dataset in the wild. In 2023 IEEE 36th In-

ternational Symposium on Computer-Based Medical

Systems (CBMS), pages 225–230. IEEE.

Richards, C., Davies, L., and Oliver, C. (2017). Predictors

of self-injurious behavior and self-restraint in autism

spectrum disorder: Towards a hypothesis of impaired

behavioral control. Journal of Autism and Develop-

mental Disorders, 47:701–713.

Richards, C., Moss, J., Nelson, L., and Oliver, C. (2016).

Persistence of self-injurious behaviour in autism spec-

trum disorder over 3 years: a prospective cohort study

of risk markers. Journal of neurodevelopmental dis-

orders, 8:1–12.

Richards, C., Oliver, C., Nelson, L., and Moss, J. (2012).

Self-injurious behaviour in individuals with autism

spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal

of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(5):476–489.

Sagar, E., Khera, S. N., and Garg, N. (2023). “i wish

they’d just let us be.” experiences of indian autistic

individuals around stimming behaviors at the work-

place. Autism in Adulthood.

Schuck, R. K., Flores, R. E., and Fung, L. K. (2019). Brief

report: Sex/gender differences in symptomology and

camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum disor-

der. Journal of autism and developmental disorders,

49:2597–2604.

Slingsby, B., Yatchmink, Y., and Goldberg, A. (2017). Typ-

ical skin injuries in children with autism spectrum dis-

order. Clinical pediatrics, 56(10):942–946.

Stevenson, P. (2020). ’stim your heart out’and’syndrome

rebel’(performance artworks, autism advocacy and

mental health). idea journal, 17(2).

Wei, P., Ahmedt-Aristizabal, D., Gammulle, H., Denman,

S., and Armin, M. A. (2023). Vision-based activity

recognition in children with autism-related behaviors.

Heliyon, 9(6).

Yates, T. M. (2004). The developmental psychopathology

of self-injurious behavior: Compensatory regulation

in posttraumatic adaptation. Clinical psychology re-

view, 24(1):35–74.

VISAPP 2025 - 20th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications

994