Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications

João Ferreira

1

, Vânia Pinto

1,2 a

, Tiago Matos

1,2 b

, Susana O. Catarino

1,2 c

, Graça Minas

1,2 d

and Paulo Sousa

1,2,* e

1

Center for Micro Electromechanical Systems (CMEMS), Universiy of Minho, Guimarães, 4800-058, Portugal

2

LABBELS — Associate Laboratory in Biotechnology and Bioengineering and Microelectromechanical Systems,

University o 7, Portugal

psousa@dei.uminho.pt

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Photoacoustics, Scanning System.

Abstract: Recently, the field of photoacoustic (PA) imaging has garnered significant attention due to its ability to

provide high-resolution images and real-time monitoring of biological tissues. However, PA systems have

relied on expensive and complex laser sources and detection mechanisms, limiting their accessibility for

widespread use in both clinical and research settings. So, this work aims to address these limitations by

presenting the development of an alternative low-cost photoacoustic system, with an estimated cost of less

than 700€, based on a Q-switched solid-state Nd:Ce:YAG nanosecond laser and a highly sensitive system for

acoustic detection. PA data acquisition and image reconstruction were implemented and validated with pencil

lead phantoms. The developed system shows a high potential to provide a low-cost tool that can be used in

several biomedical applications.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, photoacoustic (PA) has emerged as a

new sensing technology that has been applied in the

biomedical imaging field to obtain structural and

functional information of cells and tissues non-

invasively, providing highly specific molecular

images. Furthermore, this imaging technology offers

excellent spatial resolution, large imaging depth and

high optical contrast (Beard, 2011; Erfanzadeh &

Zhu, 2019; Zhu et al., 2024). It has been studied for

tumour detection, epidermal melanin measurements,

blood oxygenation monitoring, quantitative blood

flow estimation, among others (Attia et al., 2019;

John et al., 2023). Although its huge potential, the

high cost of traditional PA systems and challenges in

the miniaturization of the imaging components have

limited their accessibility and widespread use in

various fields, particularly in smaller laboratories and

developing regions.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3395-1251

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3826-6413

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8962-0710

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2460-0556

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2290-808X

*

Corresponding author.

Typically, most of the commercial and research

lab-made PA systems for biomedical applications use

solid-state lasers to irradiate their targets, however

these systems have been difficult to translate to

clinical applications, due to their high cost and bulky

size (Zhu et al., 2020). In recent years, low-cost solid-

state laser, Laser Diodes (LDs) and light emitting

diodes (LEDs) have emerged as alternative

illumination sources, for the development of less

expensive, compact and portable sensing and imaging

systems (Zhong et al., 2018). Even though LEDs and

LDs possess some disadvantages, such as low output

energy, lack of spectral tuning capability, and long

pulse widths, they are portable, affordable, and

energy-efficient light sources (Singh & Xia, 2020).

In addition, the PA systems require ultrasonic

detection methods that include piezoelectric

transducers, micromachined ultrasound transducers

(MUTs) (which can be divided into piezoelectric

micromachined ultrasound transducer (pMUT),

1092

Ferreira, J., Pinto, V., Matos, T., Catarino, S. O., Minas, G. and Sousa, P.

Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications.

DOI: 10.5220/0013399500003911

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 1092-1099

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducer

(cMUT)) and optical transducers (Manwar et al.,

2020). However, piezoelectric transducers are the

most used transducers because of their well-

established fabrication technology, reduced cost and

dimensions and scalable sensitivity.

This work addresses this challenge by presenting

the development of a novel and low-cost

photoacoustic system that utilizes an affordable

nanosecond tattoo removal laser as its light source

with a unit price of ∼€500 (compared with $20–30 k

for a regular system for PA testing and measurement)

(Zhu et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2023), significantly

reducing the typical investment required for such

technology. Complementing the laser, a commercial

lead zirconate titanate (PZT) transducer works as the

acoustic receptor, while a low-cost logarithmic

amplifier enhances the signal detection capabilities.

To validate the performance of the developed system,

experiments were conducted using pencil lead

phantoms, enabling the assessment of the

photoacoustic signal through a cost-effective

electronic circuit. In addition, a scanning system and

an image reconstruction system from the PA signals

were developed. This innovative approach not only

demonstrates the feasibility of creating an economical

PA system but also opens new avenues for research

and clinical applications that require high-quality

imaging without prohibitive costs

2 PA SYSTEM’S DESIGN AND

OPERATION

The PA effect is initiated when an pulsed

electromagnetic wave targets the sample surface.

Depending on the wavelength, the light penetrates to

some depth in the target. Photon absorption and

subsequent relaxation induce a rapid temperature rise,

leading to the thermoelastic expansion of the

absorbing target. This sudden pressure rise propagates

as a sound wave, which then can be detected using an

acoustic transducer. By detecting the pressure wave,

one can localize their sources (i.e., where the light was

absorbed) and obtain important functional and

molecular information about the studied sample. More

details about the theory and operational principles of

PA detection are described in our previous work

(Pinheiro et al., 2023; Pinheiro et al., 2024).

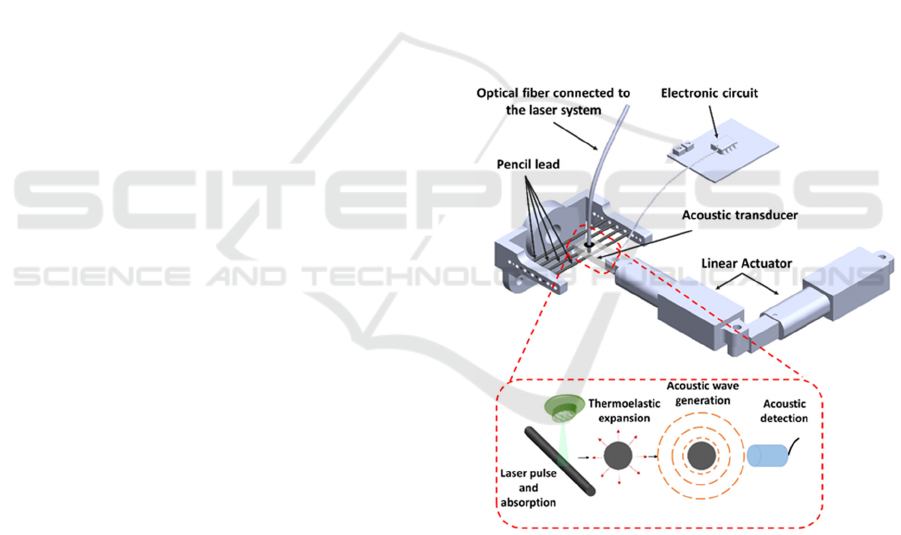

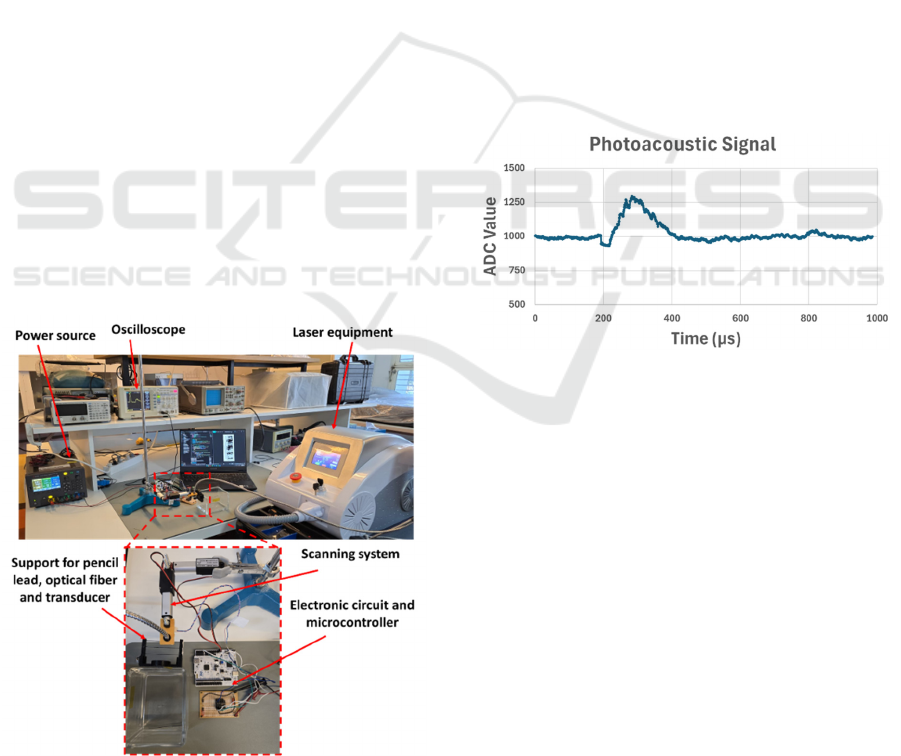

The developed PA system and the main operation

principle are presented in Figure 1. An Q-switched

solid-state Nd:Ce:YAG nanosecond laser (Ulat,

B08G8S5YHF, China), commonly used for tattoo

removal, was used as light source. This equipment

outputs 532 nm laser pulses with a pulse width of 8 ns

and 40 mJ energy at a repetition rate of 10 Hz. An

optical fiber was used to guide the light from the laser

to the sample. A packaging assembly specifically

engineered to support and align all the components,

namely the excitation light and the acoustic transducer

(PRYY+0398, PiMicos) was fabricated by 3D

printing. For the scanning measurement system, two

linear actuators (6V Push Rod, 30mm-128N, LA-T8-

6-7-3085-128) connected in a 90-degree configuration

were used to move in a controlled way the excitation

light and the acoustic transducer together. The

generated PA signals were detected by the acoustic

transducer and amplified by the electronic circuit

(AD8307 from Analog Devices). A STM

microcontroller was used to control, store and acquire

the PA signals which are sent to a PC where a phyton

program was implemented to reconstruct the image. In

the following sections, the main components of the

developed PA system are described with more detail.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the main components

of the PA detection system.

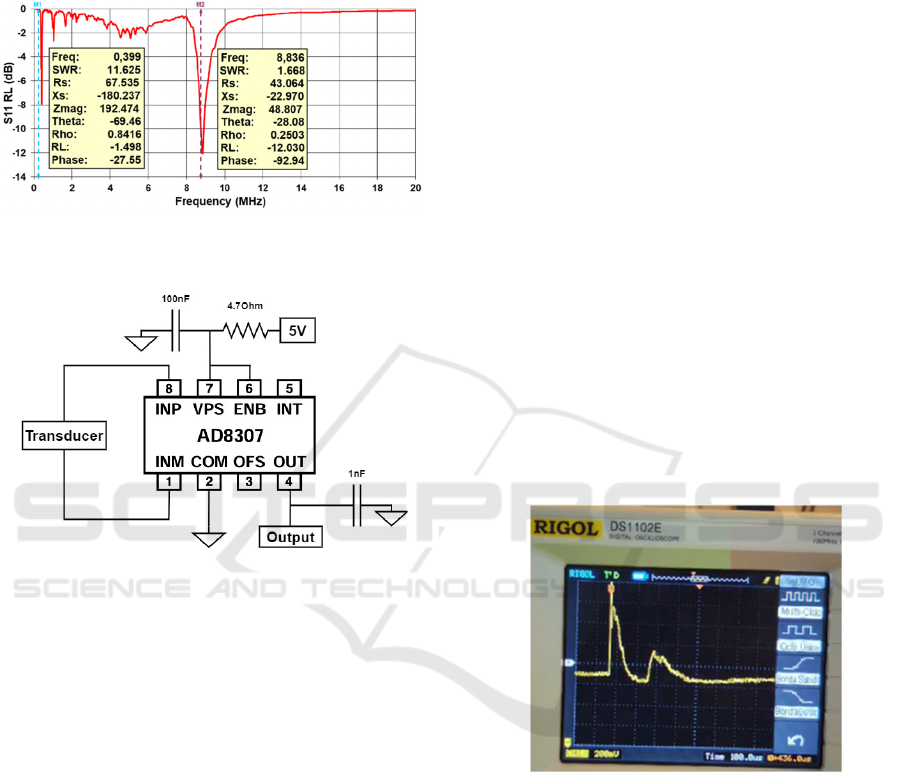

2.1 Acoustic Transducer

The detection module of the PA system uses a PZT

piezoelectric transducer with a 5 mm diameter and

250 μm thickness (PRYY+0398, PiMicos). The

transducer electrical characterization was performed

by measuring the S-parameters from 10 kHz to 20

MHz (without an impedance matching circuit), to

determine the return loss (RL), which indicates the

Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications

1093

reflected electrical power. The transducer shows RL

peaks at 400 kHz and 8.8 MHz, corresponding to the

radial and thickness resonance frequencies,

respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Return loss variation according to frequency for

the transducer from 10 kHz to 20 MHz.

Figure 3: Electrical diagram of the circuit implemented in

the amplifier.

2.2 AD8307 Amplifier

Typically, the PA signal induced by the nanosecond

pulse laser has very low intensity, requiring an

amplification circuit. For this purpose, the AD8307

integrated circuit was chosen. It is a complete 500

MHz monolithic demodulating logarithmic amplifier

based on the progressive compression (successive

detection) technique, providing a dynamic range of

92 dB to ±3 dB law conformance and 88 dB to a tight

±1 dB error bound at all frequencies up to 100 MHz.

This logarithmic amplifier is widely used in radio

frequency applications thanks to its vast list of

advantages. The AD8307 operates in a wide

frequency range, from DC up to 500 MHz, making it

suitable for both low and high-frequency

applications, and presents a wide dynamic range (-75

dBm to +15 dBm). It outputs a log-scale voltage

directly proportional to the signal power, eliminating

the need for extra circuits like rectifiers, filters, or log

converters. Compared to traditional coupling circuits

using standard operational amplifiers, the AD8307

provides an analogue output proportional to the input

energy and frequency without needing multiple

stages of amplification, attenuation, and additional

components to handle radiofrequency (RF) signals

and measure power over a wide range. In addition, it

requires minimal adjacent electronic components,

making it easy to integrate in pre-existent circuits.

The electrical diagram of the implemented circuit

is presented in Figure 3. A low-pass filter (12.7 kHz

cutoff frequency) was added to the amplifier output

to reduce high-frequency noise.

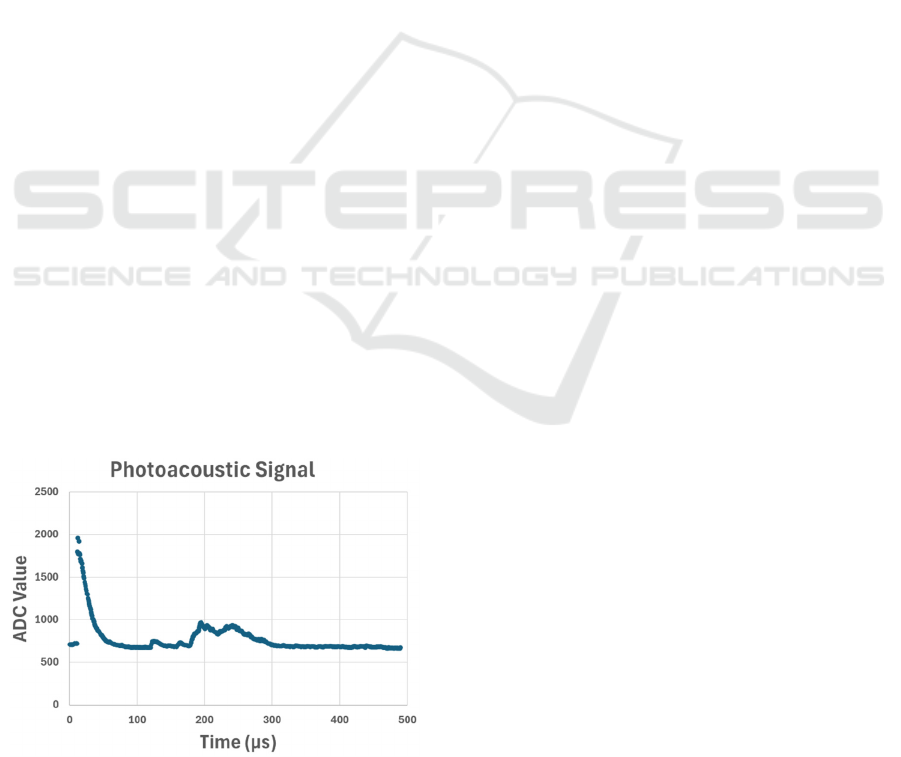

2.3 Signal Acquisition

The PA signal acquired by the amplification circuit

was initially displayed in an oscilloscope. After

validation, a signal acquisition system was

implemented using an algorithm to process the data.

For this purpose, an STM32H503RB development

board was used. This board was chosen due to its high

clock frequency, 250 MHz, which enables a very high

rate of data acquisition, thus providing a more

detailed data acquisition. This is essential for the

developed PA system since the duration of the

obtained signal is approximately 200 μs, as it can be

seen in the Figure 4.

Figure 4: Photoacoustic signal recorded by an oscilloscope.

After connecting the board to the amplification

circuit so that its output is connected to the boards’

analog to digital converter (ADC), and ensuring a

common ground between the two, the signal can be

acquired. It should be noted that the ADC has a

maximum resolution of 12 bits, meaning the highest

value it can return is 2

12

= 4095. Furthermore, given

that the maximum supported voltage by the ADC is

3.3 V, using a simple proportion, any value

transmitted by the ADC can be converted into a

voltage value using the following equation:

Voltage = (ADC value × 3.3) / 4095 (1)

EM4Health 2025 - Special Session on Electromagnetic waves for healthcare

1094

Regarding the implementation of the data

acquisition, firstly an array was created with its size

corresponding to the number of samples to be

acquired. After this, the board’s ADC is initialized

and waits to receive a value greater than 2000 to start

the acquisition. This condition was implemented to

ensure that only signals of interest are acquired;

without it, any interference, could trigger the

beginning of the process. The electromagnetic noise

caused by the laser firing is used as a trigger signal to

synchronize the STM with the photoacoustic system.

Once this condition is met, the acquisition begins, and

the array is filled. Once full, its values are transmitted

via the serial port and the array is restarted with its

values set to 0, thus allowing to restart the process,

according to the following commands:

#define array_size 2000

Void read_adc_array(){

…

HAL_ADC_Start(&hadc1);

while(val[0]<2000){

…

}

for(int i=0; i<array_size; i++){

val[i] =

(int16_t)HAL_ADC_GetValue(&hadc1);

}

HAL_ADC_Stop(&hadc1);

for (int i=0; i<array_size;i++){

…

HAL_UART_Transmit(&huart3,

uint8_t*)tx, strlen(tx), 200);

val[i]=0;

}

}

Since the data is being transmitted via serial port,

the next step is saving it to the computer. In a first

stage, the PUTTY software (v0.82) was used to

receive and store the received values, enabling the

creation of the Figure 5 plot.

Figure 5: ADC values (a.u.), related to the generated

photoacoustic signal, acquired by the microcontroller over

time (µs).

2.4 Motor Control

Having confirmed the viability of the data acquisition

using the microcontroller, it was also chosen for

another critical task: to enable the imaging of a pre-

selected region of interest (ROI). To meet this

requirement, two motors were employed, each

responsible for moving the scanning system across an

(X,Y) plane. The selected motors are linear actuators

with a maximum boom of 3 cm, operating at a voltage

of 3.3 V. This allows for the coverage of a 9 cm

2

total

area, enough to analyse the entire ROI. Moreover,

their power can be directly supplied by the

microcontroller, as well as its control algorithm, thus

simplifying the project by not having to rely on an

external motor driver.

To control the actuators, it was first necessary to

determine their velocity, to calculate how long they

need to be activated to extend a given distance.

Through multiple tests, it was found that the actuators

take approximately 14.2 seconds to reach their

maximum length. Thus, it was calculated that to move

1 mm, the active time required is 473.3 ms.

Finally, each motor is connected to two General

Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins capable of

providing voltage values between 0-3.3 V. By

toggling these pins, the direction of the movement can

be changed, as well as stopping their motion:

Void move_x_axis(){

uint32_t startTime= HAL_GetTick();

uint32_t elapsedTime = 0;

while (elapsedTime < 473){

HAL_GPIO_WritePin(GPIOC,

GPIO_PIN10, GPIO_PIN_RESET);

HAL_GPIO_WritePin(GPIOC,

GPIO_PIN_12, GPIO_PIN_SET);

elapsedTime = HAL_GetTick() –

startTime;

}

}

The last step is to ensure that the motors are

moving in a pattern that allows them to cover a

predetermined area. For this, a loop was implemented

to control their movement in a grid-like motion:

Void grid_movement(){

for(int i=0;i<10;i++){

for(int j=0;j<10;j++){

move_y();

read_adc_array();

}

home_y();

move_x();

}

home_x();

home_y();

}

Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications

1095

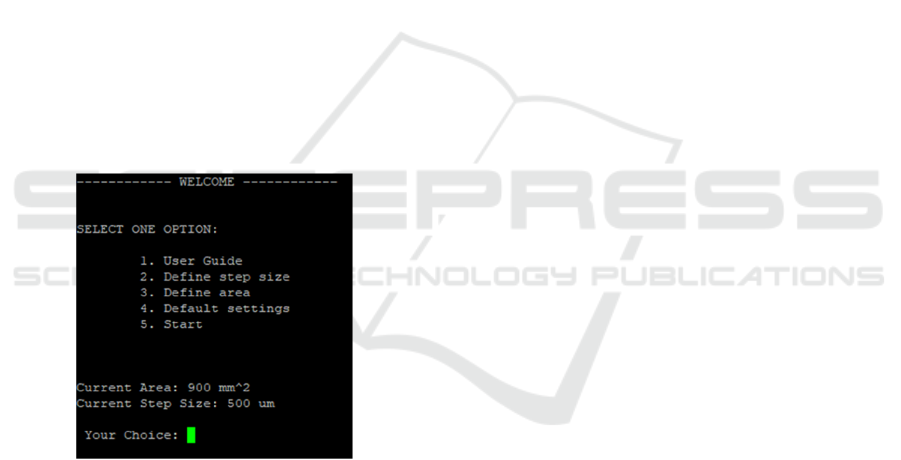

2.5 User Interface

A command-line user interface has been developed to

facilitate an efficient and intuitive interaction with the

system. By default, the system is configured to

analyse the maximum area with a resolution of

500 μm per step. However, the interface provides

several configurable options to better align the

system's operation with specific application

requirements.

The available features include: a user guide to

explain how the system works, Step Size Adjustment

that enables modification of the resolution of the step

size and analysis area configuration that allows

customization of the area to be analysed, optimizing

the process for various applications (Figure 6).

Due to the resource limitations of the STM32

platform, all interactions are conducted through the

command-line interface, as implementing a graphical

user interface (GUI) would be impractical.

Parameters defined by the user via this interface are

automatically transferred to the accompanying

Python script running on a connected computer. This

ensures that the generated graphical output adheres to

the specified parameters.

Figure 6: Example of the User Interface.

2.6 Data Analysis

Having successfully acquired the required data using

the microcontroller and established a method for

controlling the system's position, the final step

involves implementing an algorithm to analyse the

data and present it in a clear and user-friendly

interface. To achieve that, a Python script was

developed to read the serial port of the computer, save

the received data locally on the machine and do the

necessary processing. Firstly, some parameters

needed to be set, namely the port being used, its baud

rate and the amount of data points being received. The

next step is to initialize the connection and read the

data:

try:

ser = serial.Serial(COM_PORT, BAUD_RATE)

print(f"Connected to {COM_PORT} at

{BAUD_RATE} baud.")

except serial.SerialException as e:

print(f"Error connecting to

{COM_PORT}: {e}")

exit()

After a successful connection, the data is stored in

an array which, when filled with the total points, is

saved in a .txt file.

while len(data) < TOTAL_POINTS:

line = ser.readline().decode('utf-8',

errors='ignore').strip()

file.write(line + "\n") # Save the line

to the file

Now that all the data has been received, some

conditioning needs to be done so that it reflects real-

world conditions. For now, the array is storing all the

values in the order they were transmitted but, since

every measurement consists of 2000 data points, the

main array needs to be subdivided into smaller ones

with 2000 entries each. After this subdivision has

taken place, the next step is to focus on the entries

which contain the photoacoustic signal. As seen on

Figure 5, the signal starts roughly 150 μs after the

electromagnetic discharge produced by the laser and

has a duration of 150-200 μs. To only interpret the

data points stored in those positions, the maximum

value of the array needs to be found:

def find_max_per_chunk(data,

chunk_size):

max_values = []

for i in range(0, len(data),

chunk_size):

chunk = data[i:i +

chunk_size]

max_values.append(max(chunk))

return max_values

Knowing in which position the electromagnetic spike

occurs, the next step is to trim the initial array that

contains 2000 entries into smaller ones that only

contain the values present from 150 μs to 300 μs.

Since we know that each entry occurs at intervals of

0.7 μs, we know that is going to be roughly taking

place around sample number 200-400.

EM4Health 2025 - Special Session on Electromagnetic waves for healthcare

1096

def extract_values_after_max(data,

chunk_size, offset_start, offset_end):

extracted_values = []

for i in range(0, len(data),

chunk_size):

chunk = data[i:i +

chunk_size]

max_idx = chunk.index(max(chunk

start_idx = max_idx +

offset_start

end_idx = max_idx + offset_end

if start_idx < len(chunk):

extracted_values.append(chu

nk[start_idx:min(end_idx, len(chunk))])

return extracted_values

offset_start = 200

offset_end = 400

values_after_max =

extract_values_after_max(data,

chunk_size, offset_start, offset_end)

The last step is to find the maximum value inside

these new chunks of data, which will tell us if there is

any PA response and represent it in a cartesian graph

that will allow the data visualization. The values are

presented in a grayscale where the minimum value is

represented by the color black and the maximum by

the color white.

3 EXPERIMENTAL SETUP FOR

THE PA SYSTEM TEST

Figure 7: Setup for the experimental tests.

The experimental tests were conducted with the setup

shown in Figure 7, which comprises the power source

used to supply the amplifier circuit and the

microcontroller; the amplification circuit and the

STM32 H503RB; the support for sample, optical

fiber and transducer and the laser equipment,

responsible for the light excitation.

To validate the PA system, several pencil lead

phantoms were employed. A matrix of pencil lead

(Graphite HB 0.7 mm), arranged in 4 rows with a

spacing of about 5 mm, was fabricated using 3D

printed plastic holders. Using this solution allows us

to keep the low cost of the tests and ensure

reproducibility. In addition, the high content of

carbon in the pencil lead allows obtaining strong

photoacoustic signals (Zou et al., 2023).

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A first test with a single pencil lead was performed to

observe the maximum peak output and evaluate the

PA signal (Figure 8).

Figure 8: ADC values (a.u.), related to the generated

photoacoustic signal, after processing, as a function of time

(µs).

As can be seen, a constant signal was received by

the ADC with an approximate value of 1000, which

equates to 0.805 V (-57.8 dB). When the PA response

is triggered, a spike can be seen, reaching the value of

1300, which represents 1.05 V (-48 dB), an increase

of 0.245 V over the constant value generated by the

circuit. After the previous validation, a test with all

the modules was performed. A scanning area of 200

mm

2

was defined for the test, corresponding to an X

distance of 5 mm and an Y distance of 40 mm,

allowing measuring the PA response of four pencil

lead lines. One acquisition was made at each

coordinate, which was then processed to PA image

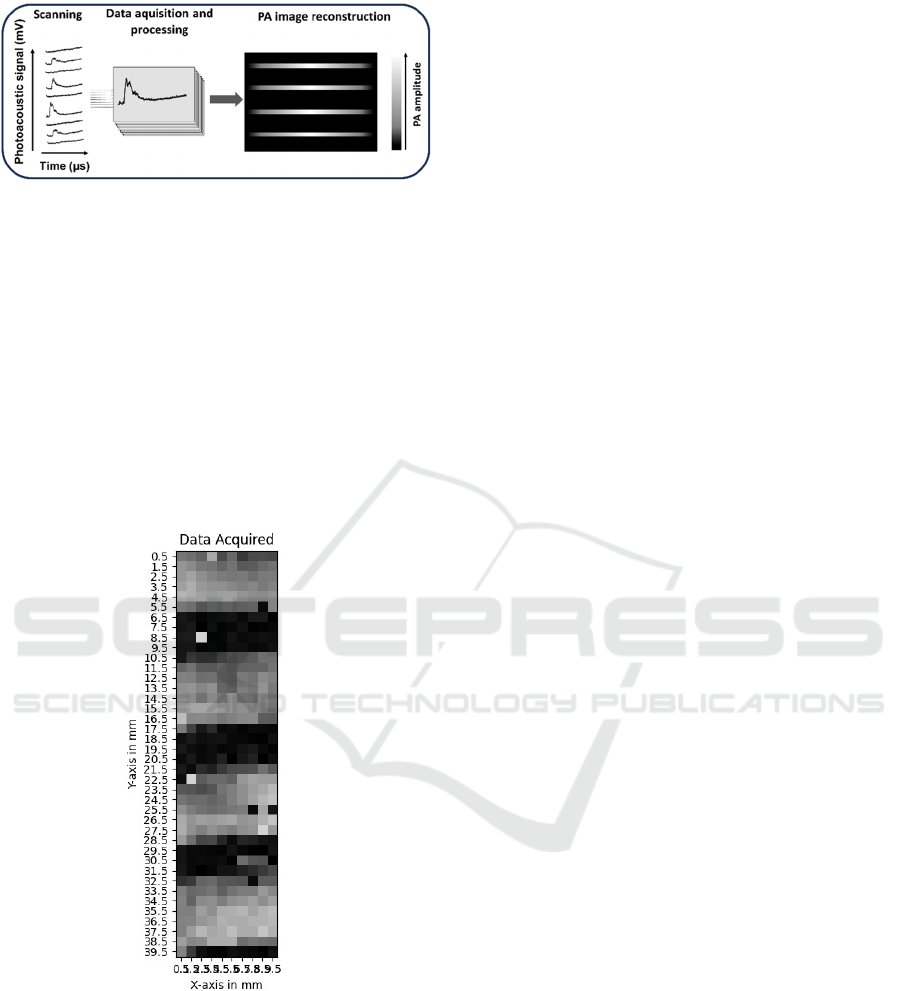

reconstruction. The schematic representation of the

main steps for data acquisition, processing and

reconstruction are presented in Figure 9.

Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications

1097

Figure 9: Schematic representation of the main steps of PA

image reconstruction.

The reconstructed final image, in Figure 10,

shows the capability of the developed system to map

the spatial distribution of all four targets (pencil lead),

where the color shifts from black to white. Although

it is possible to identify four distinct regions,

coinciding with the position of the graphite, the lateral

resolution presents some limitations in accurately

discriminating the separation between them. This

limitation can be improved by reducing the laser focal

point to decrease the irradiation area and increase the

potential of the developed system.

Figure 10: 2D Image reconstructed from the PA signals of

the four pencil leads.

5 BIOMEDICAL APPLICATIONS

OF PHOTOACOUSTIC

SYSTEMS

The developed PA imaging system can be used in

several biomedical applications, namely in

microfluidic lab-on-a-chip devices to monitor

haemoglobin quantities (Pinheiro et al., 2024), or in

organ-on-a-chip devices to provide, for example, a

mapping of the spatial distribution of drugs (such as

the antitumor drug doxorubicin) within cells or

tissues, in a continuous way. The real-time

monitoring of the cell’s response to new compounds

allows has potential to accelerate the clinical

translation of new vaccines and drugs. In addition, it

can have a significant impact on the understanding of

the efficiency of new drugs, which potential to lower

the amount of drugs needed for the treatment of

diseases, decreasing their side effects and ensuring

better population ageing conditions.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents a detailed characterization of the

development and validation of a low-cost

photoacoustic system, with high potential for future

application in biomedical devices.

Using pencil lead phantoms, the developed

system was able to detect the PA signals and

reconstruct the corresponding image with good

accuracy.

Future improvements are needed to increase the

lateral resolution of the system, namely with the use

of optical lenses to reduce the area of the incident

light.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by the project

DrugSENS (2022.02165.PTDC) (https://doi.org/10.

54499/2022.02165.PTDC), through national funds

(OE), within the scope of the Scientific Research and

Technological Development Projects (IC&DT)

program in all scientific domains (PTDC), through

the Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P.

(FCT, I.P). The authors also acknowledge the partial

financial support within the R&D Unit Project Scope:

UIDB/04436/2020. Susana Catarino, Paulo Sousa

and Vânia Pinto thank FCT for their contracts funding

provided through 2020.00215.CEECIND

(DOI: https://doi.org/10.54499/2020.00215.CEECIN

D/CP1600/CT0009), 2021.01086.CEECIND

(https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.01086.CEECIND/CP

1664/CT0008) and 2021.01087.CEECIND

(https://doi.org/10.54499/2021.01087.CEECIND/CP

1664/CT0020), respectively.

EM4Health 2025 - Special Session on Electromagnetic waves for healthcare

1098

REFERENCES

Attia, A. B. E., Balasundaram, G., Moothanchery, M.,

Dinish, U. S., Bi, R., Ntziachristos, V., & Olivo, M.

(2019). A review of clinical photoacoustic imaging:

Current and future trends. Photoacoustics, 16, 100144.

Beard, P. (2011). Biomedical photoacoustic

imaging. Interface focus, 1(4), 602-631.

Erfanzadeh, M., & Zhu, Q. (2019). Photoacoustic imaging

with low-cost sources; a review. Photoacoustics, 14, 1.

John, S., Hester, S., Basij, M., Paul, A., Xavierselvan, M.,

Mehrmohammadi, M., & Mallidi, S. (2023). Niche

preclinical and clinical applications of photoacoustic

imaging with endogenous contrast. Photoacoustics,

100533.

Singh, M. K. A., & Xia, W. (2020). Portable and affordable

light source-based photoacoustic tomography. Sensors

20(21), 6173.

Manwar, R., Kratkiewicz, K., & Avanaki, K. (2020).

Overview of ultrasound detection technologies for

photoacoustic imaging. Micromachines, 11(7), 692.

Pinheiro, B. R, Dinis, H. D., Catarino, S. O., Pinto, V. C.,

Sousa, P. J., & Minas, G. (2023, June). Experimental

Characterization of a Piezoelectric Transducer for

Integration into a Photoacoustic System. In 2023 IEEE

7th Portuguese Meeting on Bioengineering

(ENBENG) (pp. 84-87). IEEE.

Pinheiro, B., Pinto, V., Dinis, H., Belsley, M., Catarino, S.,

Minas, G., & Sousa, P. (2024). Development of a

Photoacoustic Acquisition System and their Proof-of-

Concept for Hemoglobin Detection. Heliyon.

Zhong, H., Duan, T., Lan, H., Zhou, M., & Gao, F. (2018).

Review of low-cost photoacoustic sensing and imaging

based on laser diode and light-emitting

diode. Sensors, 18(7), 2264.

Zhu, X., Menozzi, L., Cho, S. W., & Yao, J. (2024). High

speed innovations in photoacoustic microscopy. npj

Imaging, 2(1), 46.

Zhu, Y., Feng, T., Cheng, Q., Wang, X., Du, S., Sato, N., ...

& Kuniyil Ajith Singh, M. (2020). Towards clinical

translation of LED-based photoacoustic imaging: a

review. Sensors, 20(9), 2484.

Zou, E., Fang, C., & Song, D. (2023). A Low-Cost

Handheld Photoacoustic (PA) Probe for Rapid and

Non-Destructive Detection of Watermelon

Ripeness. IEEE Sensors Journal.

Low-Cost Photoacoustic System for Biomedical Applications

1099