Comparative Analysis of Mechanically Induced Long Period

Gratings Using Different 3D Printed Grooved Structure Shapes

Sidrish Zahra

a

, Elena De Vita

b

, Flavio Esposito

c

, Agostino Iadicicco

d

and

Stefania Campopiano

e

Department of Engineering, University of Naples “Parthenope”, 80143 Naples, Italy

Keywords: 3D Printing, Long Period Gratings, Mechanically Induced Long Period Gratings, Double Cladding Fibers,

Photonic Crystal Fibers.

Abstract: This study deals with mechanically induced long period fiber gratings (MILPGs). First, an in-depth analysis

of the most effective grating configuration of a grooved structure featuring a duty cycle of 40:60 using SMF-

28 is provided. Subsequently, a comparative analysis of MILPGs developed in various multi-layered optical

fibers, including double cladding fibers with doped and pure-silica core as well as solid core photonic crystal

fiber is presented. The demonstrated fabrication method highlights its adaptability for various types of fibers,

eliminating the need for supplementary equipment or modifications, and operates independently of

photosensitive fibers which marks the novelty of this work.

1 INTRODUCTION

Optical fiber sensing has attracted much attention due

to its high sensitivity, immunity to electromagnetic

interference, corrosion resistance, long-distance

telemetry, multiplexing, embedding in engineering

structures, and distributed measurement (Addanki et

al., 2018) and therefore can be used as sensing

elements to detect several parameters such as

mechanical measurements (Drake et al., 2018),

chemical and biological properties (Wolfbeis, 2006;

Yin et al., 2018), temperature (Schena et al., 2016), and

biomedical parameters (Leal-Junior et al., 2019).

Moreover, devices utilizing fiber gratings and

especially long period gratings (LPGs) are among the

most extensively studied, owing to their diverse

applications in optical communication and sensing

systems.

The LPG period is large generally tens to

hundreds of microns. It can couple the core mode to

the cladding modes propagating along the same

direction, causing transmission loss of a specific

wavelength.

LPG has the advantages of extremely

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0000-4237-7650

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4975-2775

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1187-5825

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3540-7316

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2987-9122

low back reflection, full compatibility with optical

fiber and low insertion loss. In the field of optical

fiber communication, it can be used as a band-stop

filter (Vengsarkar et al., 1996), mode converter or

grating coupler (Liu et al., 2007); and in the field of

optical fiber sensing, it can be used for single

parameter or multi-parameter sensing such as

temperature, refractive index and bending (Bhatia et

al., 1999).

Over the past few decades, LPG

preparation methods have emerged in an endless

stream, rich and diverse. In addition to the very

mature UV exposure method (Kalachev et al., 2005),

there are also ion beam irradiation method (von Bibra

et al., 2001), arc discharge method (Esposito et al.,

2019) and so on.

The formation mechanisms of these

preparation methods are different, which makes the

application fields of written LPG also very different.

Every fabrication technique presents unique

benefits, yet it is important to acknowledge the

inherent limitations as well. For instance, permanent

grating can be established using several of the

previously mentioned methods. The UV laser

technique is limited to photosensitive fiber, and in the

Zahra, S., De Vita, E., Esposito, F., Iadicicco, A. and Campopiano, S.

Comparative Analysis of Mechanically Induced Long Period Gratings Using Different 3D Printed Grooved Structure Shapes.

DOI: 10.5220/0013400600003902

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Photonics, Optics and Laser Technology (PHOTOPTICS 2025), pages 163-167

ISBN: 978-989-758-736-8; ISSN: 2184-4364

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

163

case of the arc discharge method, fiber bending

during fabrication could impact real-time monitoring.

An alternative technique known as mechanically

induced long period grating (MILPGs) exists. Due to

the photo-elastic effect, a periodic refractive index

modulation is generated at a pressure point on the

optical fiber to form a mechanically induced LPG.

This method has a simple structure. Since then,

MILPG has attracted widespread attention from

scholars at home and abroad, and different structures

of force-applying devices have been continuously

proposed and are widely used in the fields of optical

fiber communication and sensing (Lee et al., 2020;

Savin et al., 2000), (Rego et al., 2003), (Yokouchi et

al., 2005), (Oliveira et al., 2021).

Recently, there has been a growing interest in

additive manufacturing technologies for the creation

of 3D objects tailored for optical fiber devices (Iezzi

et al., 2016). This technology has emerged as the

favoured option among the diverse array of available

solutions, owing to several appealing characteristics,

including affordability, rapid design and production

capabilities, on-demand printing, the ability to

process polymer materials and, crucially, printing of

complex geometries with high resolution (Di Palma

et al., 2022).

In this context, this study employed

Stereolithography (SLA) 3D printing for the

fabrication of mechanically induced long period

gratings in different unconventional optical fibers for

a specific period of 630 μm. This printing technique

not only delivers exceptional detail and surface

quality but also enhances material efficiency, as only

the resin directly exposed to the light undergoes

solidification. The MILPGs are fabricated mainly due

to the combined influence of cyclic mechanical strain

applied to the fiber generated by the interdigitated 3D

printed structure.

2 3D – PRINTING BASED

FABRICATION OF MILPG

The fabrication of mechanically induced long-period

gratings using 3D printing techniques has become a

highly regarded approach in recent years (Oliveira et

al., 2021). The creation of MILPGs usually requires

the utilization of a 3D-printed structure to generate

periodic deformations along the optical fiber,

resulting in the formation of the grating pattern. The

process starts by creating and printing a unique

structure that will be utilized to manipulate the shape

of the optical fiber. As the fundamental component of

the fabrication process, which causes alteration in the

physical or geometrical characteristics of the fiber, is

the periodically grooved structure. The process starts

by carefully designing 3D CAD (Computer-Aided

Design) files. Once the CAD files for 3D model are

completed, they are printed using a commercial 3D

Anycubic printer. The designing and optimization of

grating parameters and their effects have been

explained and presented in (Zahra et al., 2023).

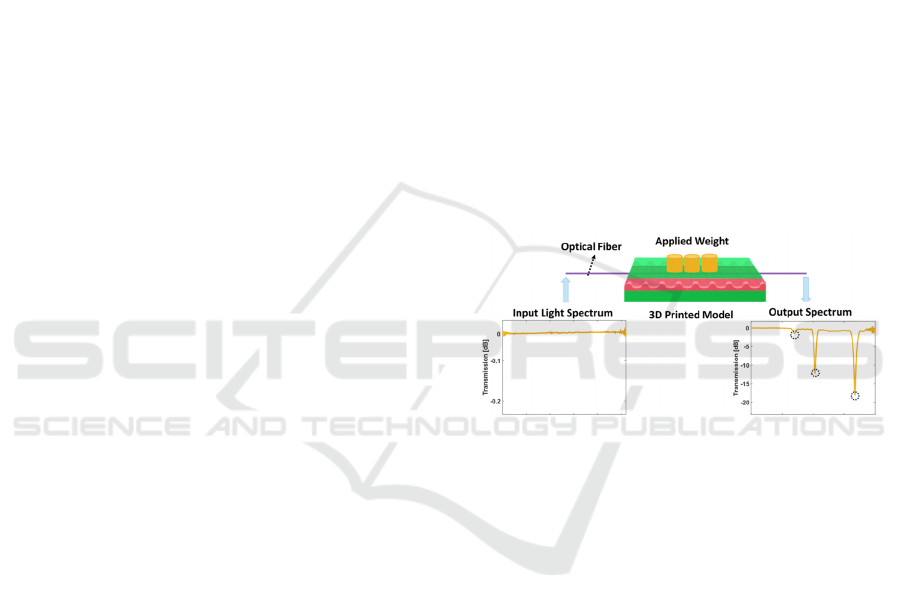

The evaluation of the performance of our

proposed technique to produce the MILPGs was

conducted utilizing the configuration illustrated in

Figure 1. The experimental configuration is basic and

easy to implement, incorporating a broadband light

source alongside an Optical Spectrum Analyzer

(OSA) to assess the spectral characteristics of the

gratings. To realize the MILPGs, an optical fiber is

strategically placed on the base structure (which has

a grooved structure in the centre) and subsequently

shielded by a cover (has same grooved structure as of

base) produced from a 3D printer.

Figure 1: Schematic of Experimental setup for MILPGs.

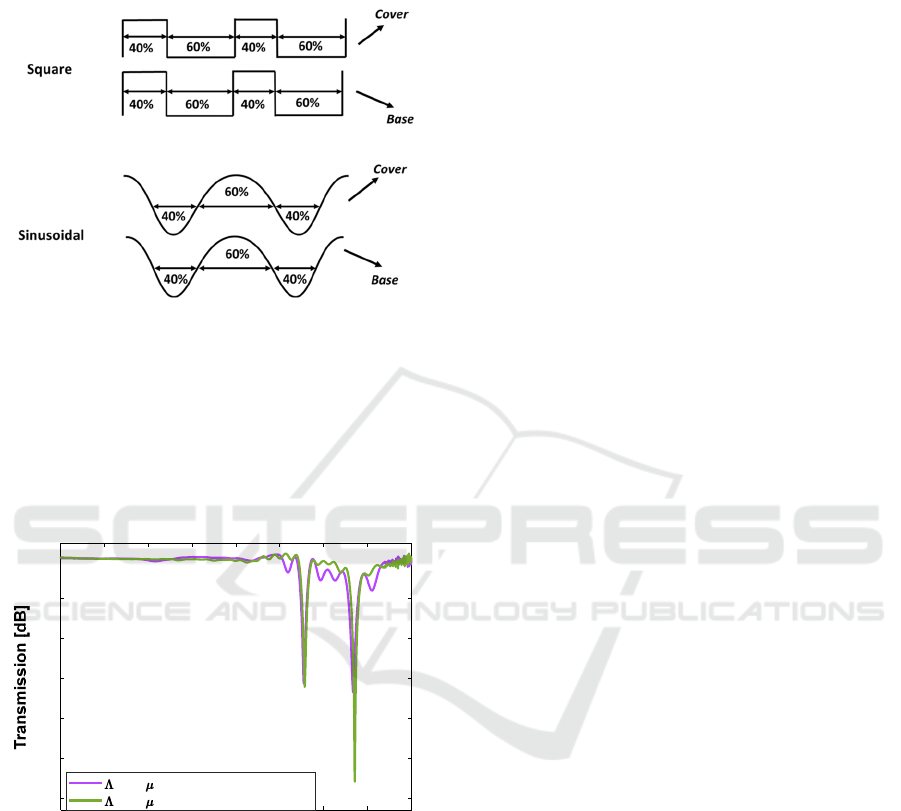

2.1 Effect of Grating Shape

This study examined the attenuation bands of the

MILPGs for two different grating shapes: 1)

sinusoidal interdigitated and 2) square shape as

depicted in Figure 2. The analysis did not involve

removing the external coating of the optical fiber. For

this experiment, a sample of externally removed

coated standard single mode fiber (SMF-28) was used

and tested for a period of 660 μm (as an example)

with an optimized grating length of 39.5 mm.

For our initial approach, we utilized a square

interdigitated grating style with a duty cycle of 40:60.

This design involved creating grooved structures on

both the base and cover of a 3D object for MILPG.

During the design and testing process, a square shape

with interdigitated features was observed to exhibit

two attenuation bands at specific wavelengths as can

be seen in Figure 3. These bands, referred to as λ

1

and

λ

2

, were located at 1577.4 nm and 1633.6 nm,

respectively. The depth of attenuation for λ

1

was

AOMatDev 2025 - Special Session on Advanced Optical Materials and Devices

164

measured at 15.7 dB, while λ

2

had a depth of 16.7 dB.

These results were obtained using an applied weight of

1614 g.

Figure 2: Schematic of interdigitated sinusoidal and square

geometry for our MILPFGs using SMF-28 (660 μm).

In the next attempt, a sinusoidal interdigitated

grating shape was designed and tested. The results

revealed the presence of two attenuation bands, one

at 1635.6 nm and another at 1578.4 nm. These bands

exhibited depths of 27.9 dB and 16 dB respectively,

when an applied weight of 1735 g was used.

Figure 3: Comparison of interdigitated sinusoidal and

square geometry for our MILPFGs using SMF-28 (660

μm).

When comparing these two distinct shapes, it is

interesting to note that both produced attenuation

bands located at similar wavelengths, but the

sinusoidal interdigitated grating style showed a

remarkably high depth of attenuation bands.

Additionally, the sinusoidal interdigitated shape had

narrower attenuation bands with fewer ripples

compared to the square interdigitated shape, as

presented in Figure 3. This feature makes it the

perfect option for creating MILPGs in optical fiber

for future applications.

2.2 MILPGs in Unconventional Fibers

Starting from the results reported in the previous

section about the shape of grooved structure, we

evaluate the versatility of fabricating MILPGs by

selecting a period of 630 μm (and optimized grating

length of 37.4 mm), for different types of multi-

layered unconventional optical fibers including i)

Thorlabs DCF-13 progressively three-layered double

cladding fiber (DCF); ii) pure-silica core Nufern

S1310 DCF with W-type structure; iii) NKT ESM-

12-01 solid core pure-silica photonic crystal fiber

(PCF). The DCF-13 represents a commercially

available double cladding fiber meticulously

developed to facilitate both single-mode and multi-

mode operation via its core and the very first

cladding. It has core diameter D

co

equal to 9 μm and

an inner cladding with diameter D

cl,in

equal to 105 μm

while the outer cladding has a diameter of D

cl,out

equal

to 125 μm. Like DCF-13, the Nufern S1310 has three

concentric layers: core, inner cladding, and outer

cladding. The fibre has a 9 μm diameter core made of

pure silica. The inner cladding, doped with fluorine,

has a diameter of 95 μm, while the outside cladding,

constructed of pure silica, has a diameter of 125 μm.

Moreover, a PCF was considered with a solid core

region with a diameter of 12 µm, while the cladding

region with a diameter of 60 µm is micro-structured

with periodic air holes.

The test used the identical experimental setup

presented in Figure 1. The preliminary evaluation of

the mechanically induced long period grating focused

on assessing its compatibility with unconventional

fibers. This investigation provides a concise overview

of the fabrication process of MILPGs implemented

for the 630 μm period, specifically for DCF-13 fiber.

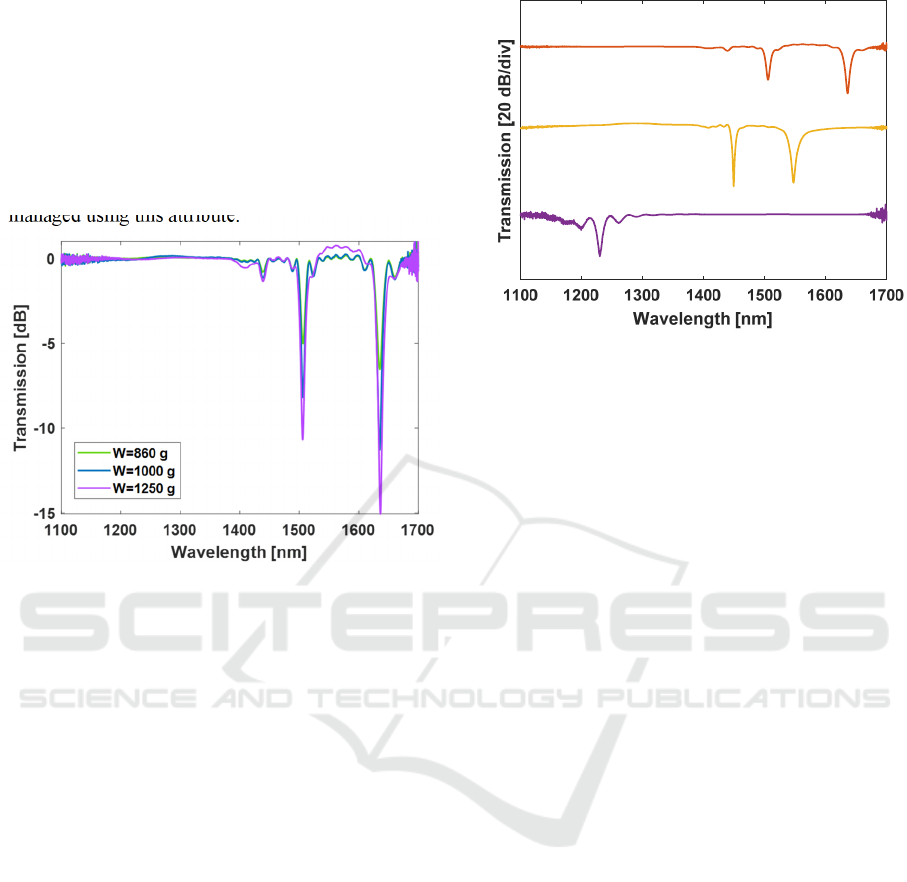

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of the

transmission spectra as the applied weight was

systematically increased from 860 g to 1250 g. As it

can be seen from the Figure 4 that weights below 860

g created insignificant transmission spectra

attenuation regions. As weight reached a specific

value, attenuation bands got more noticeable,

reaching up to 7 dB. Additional weight increased

depth to 15 dB at 1250 g. Even though not indicated

here, over-coupling reduces attenuation band depth as

the applied weight exceeds 1250 g. According to LPG

operating concept, the depth of the attenuation band

grows with modulation intensity (in this case applied

weight) until it reaches a maximum value, then drops.

The results showed three attenuation bands at 1636,

1300 1350 1400 1450 1500 1550 1600 1650

Wavelen

g

th [nm

]

-30

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

=660 m , Square geometry

=660 m , Sinusoidal geometry

Comparative Analysis of Mechanically Induced Long Period Gratings Using Different 3D Printed Grooved Structure Shapes

165

1506, and 1439 nm. The bands had maximum depths

of 15 dB, 11 dB, and 1 dB, respectively, due to the

interaction between the core mode and the 3rd, 2nd,

and 1st order cladding modes (λ

3

, λ

2

, and λ

1

). It can

be noticed that the intensity of mode coupling

increases with weight, resulting in a stronger

resonance (Figure 4). Weight affects attenuation band

intensification, but resonant wavelengths remain

fixed and ultimately peak progression is precisely

managed using this attribute.

Figure 4: Transmission spectra of DCF-13 for 630

μm with

an optimized grating length of 37.8 mm

.

The same procedure was followed for the rest of

the reported optical fibers and their measured spectra

are presented in Figure 5, where it can be seen that

when Nufern S1310 fiber was tested, two attenuation

bands were found at 1547 nm (λ

3

) and 1449 nm (λ

2

),

with maximum depths of 19 dB and 20 dB,

respectively, with 1614 g of weight applied. It can be

concluded that the utilization of DCF-13 allows for

the generation of attenuation bands with maximum

depth while requiring a reduced amount of applied

weight. Nufern fiber exhibits a slightly greater depth

for the attenuation band compared to DCF-13,

however with an increased weight relative to DCF-

13.

The same LPG period of 630 μm used in DCF-13

and Nufern S1310 was used to study grating

generation in photonic crystal fibre. As the

experimental setup shows that weight on the 3D

printed structure symmetrically distributes

mechanical stress. This microbending of the fiber in

the grooved structure deforms the air hole structure of

the PCF which ultimately changes the refractive

index and helps core-cladding coupling. The acquired

MILPG transmission spectra in PCF is illustrated in

Figure 5. The attenuation band is clearly observed at

a wavelength of 1230 nm, exhibiting a depth of 14 dB

Figure 5: Transmission spectra of different fibers for

630

μm period with an optimized grating length of 37.8

mm.

when an applied weight of only 790 g was utilized.

For photonic crystal fibres, the potential to achieve

attenuation bands with significant depth is realised,

although these bands may be broader compared to

those found in DCF-13 and Nufern S1310. In

conclusion, it is observed that for DCF-13 and Nufern

S1310, coupling was successfully achieved up to the

third order cladding mode. In contrast, for PCF,

coupling was limited to the first order over a distance

of 630 μm, which may influence aspects such as

sensing performance, explained in detail in (Zahra et

al., 2024)

3 CONCLUSION

The present study details the innovative fabrication of

mechanically induced long period gratings within

diverse multi-layered silica fibers, including two

varieties of double cladding fibers (featuring

progressively three-layered and W-type structures)

and solid core photonic crystal fiber, utilizing a 3D

printing technique for the first time in accordance

with the latest advancements in the field. A concise

examination of the fabrication of MILPGs was

performed for the aforementioned fibers, and their

transmitted spectra were evaluated within the

wavelength range of 1100-1700 nm. The devices

demonstrate remarkable spectral properties, featuring

low power losses, precise depth, and narrow

attenuation bands, achieved through an easy and

economical approach. The findings highlight the

adaptability of our proposed technology, which works

irrespective of photosensitive fibers. This capability

enables its application to various types of fibers

λ

1

λ

2

λ

3

λ

2

λ

1

λ

3

DCF-13

Nufern

PCF

AOMatDev 2025 - Special Session on Advanced Optical Materials and Devices

166

without the need for supplementary equipment or

modifications.

REFERENCES

Addanki, S., Amiri, I. S., & Yupapin, P. (2018). Review of

optical fibers-introduction and applications in fiber

lasers. Results in Physics, 10, 743–750.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2018.07.028

Bhatia, V., Glenn, W. H., Farina, J. D., Leonberger, F. J.,

Vengsarkar, A. M., Lemaire, P. J., Judkins, J. B., Bhatia,

V., Sipe, J. E., & Ergodan, T. E. (1999). Applications of

long-period gratings to single and multi-parameter

sensing. OPTICS EXPRESS, 4, 225.

https://doi.org/10.1364/OA_License_v1#VOR

Di Palma, P., De Vita, E., Iadicicco, A., & Campopiano, S.

(2022). 3D Shape Sensing With FBG-Based Patch:

From the Idea to the Device. IEEE Sensors Journal, 22,

1338–1345.

https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3133704

Drake, D. A., Sullivan, R. W., & Wilson, J. C. (2018).

Distributed strain sensing from different optical fiber

configurations. Inventions, 3(4).

https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3040067

Esposito, F., Srivastava, A., Campopiano, S., & Iadicicco,

A. (2019). Sensing Features of Arc-induced Long Period

Gratings. 29.

https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019015029

Iezzi, V. L., Boisvert, J.-S., Loranger, S., & Kashyap, R.

(2016). 3D printed long period gratings for optical

fibers. Optics Letters, 41(8), 1865.

https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.41.001865

Kalachev, A. I., Pureur, V., & Nikogosyan, D. N. (2005).

Long-period fiber grating inscription by high-intensity

femtosecond UV laser pulses. Quantum Electronics and

Laser Science Conference (QELS), 2, 951–953.

https://doi.org/10.1109/qels.2005.1548993

Leal-Junior, A. G., Diaz, C. A. R., Avellar, L. M., Pontes,

M. J., Marques, C., & Frizera, A. (2019). Polymer

optical fiber sensors in healthcare applications: A

comprehensive review. In Sensors (Switzerland) (Vol.

19, Issue 14). MDPI AG.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s19143156

Lee, J., Kim, Y., & Lee, J. H. (2020). A 3-D-printed,

temperature sensor based on mechanically-induced long

period fibre gratings. Journal of Modern Optics, 67(5),

469–474.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09500340.2020.1737741

Liu, Y., Chiang, K. S., Rao, Y. J., Ran, Z. L., & Zhu, T.

(2007). Light coupling between two parallel CO2-laser

written long-period fiber gratings. Opt. Express, 15(26),

17645–17651. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.15.017645

Oliveira, R., Sousa, L. M., Rocha, A. M., Nogueira, R., &

Bilro, L. (2021). Uv inscription and pressure induced

long-period gratings through 3d printed amplitude

masks. Sensors, 21(6), 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.3390/s21061977

Rego, G., Fernandes, J. R. A., Santos, J. L., Salgado, H. M.,

& Marques, P. V. S. (2003). New technique to

mechanically induce long-period fibre gratings. Optics

Communications, 220(1–3), 111–118.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0030-4018(03)01374-9

Savin, S., Digonnet, M. J. F., Kino, G. S., & Shaw, H. J.

(2000). Tunable mechanically induced long-period fiber

gratings. Optics Letters, 25(10), 710.

https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.25.000710

Schena, E., Tosi, D., Saccomandi, P., Lewis, E., & Kim, T.

(2016). Fiber Optic Sensors for Temperature Monitoring

during Thermal Treatments: An Overview. Sensors

(Basel, Switzerland), 16.

https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:4964243

Vengsarkar, A. M., Lemaire, P. J., Judkins, J. B., Bhatia, V.,

Erdogan, T., & Sipe, J. E. (1996). Long-period fiber

gratings as band-rejection filters. Journal of Lightwave

Technology, 14(1), 58–64.

https://doi.org/10.1109/50.476137

von Bibra, M. L., Roberts, A., & Canning, J. (2001).

Fabrication of long-period fiber gratings by use of

focused ion-beam irradiation. Opt. Lett., 26(11), 765–

767. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.26.000765

Wolfbeis, O. S. (2006). Fiber-Optic Chemical Sensors and

Biosensors. Analytical Chemistry, 78(12), 3859–3874.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ac060490z

Yin, M., Gu, B., An, Q.-F., Yang, C., Guan, Y. L., & Yong,

K.-T. (2018). Recent development of fiber-optic

chemical sensors and biosensors: Mechanisms,

materials, micro/nano-fabrications and applications.

Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 376, 348–392.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2018.08.001

Yokouchi, T., Suzaki, Y., Nakagawa, K., Yamauchi, M.,

Kimura, M., Mizutani, Y., Kimura, S., & Ejima, S.

(2005). Thermal tuning of mechanically induced long-

period fiber grating. Applied Optics, 44(24), 5024.

https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.44.005024

Zahra, S., De Vita, E., Esposito, F., Iadicicco, A., &

Campopiano, S. (2024). Mechanically induced long

period gratings in different silica multi-layered optical

fibers. Optical Fiber Technology, 85.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yofte.2024.103814

Zahra, S., Di Palma, P., De Vita, E., Esposito, F., Iadicicco,

A., & Campopiano, S. (2023). Investigation of

mechanically induced long period grating by 3-D

printed periodic grooved plates. Optics and Laser

Technology, 167.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109752

Comparative Analysis of Mechanically Induced Long Period Gratings Using Different 3D Printed Grooved Structure Shapes

167