Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept

Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care

Process Simulations

Fanny Apelgren

a

, Mattias Seth

b

, Hoor Jalo

c

, Bengt Arne Sjöqvist

d

and

Stefan Candefjord

e

Department of Electrical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden

Keywords: Synthetic Health Data, Digital Health Sandbox, Simulations, Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Fall

Accidents, Stroke, Trauma, Motor Vehicle Crashes, Virtuality, Virtual Care Process Simulator.

Abstract: To design effective and safe IT systems for healthcare is a significant technical and societal challenge, and it

is of highest importance to confirm safety of patients when implementing new innovations. It would be

beneficial if new innovations could be verified and validated in a realistic and safe digital environment using

data that preserve patient integrity and safety, before going into real clinical trials and market release. In this

article we introduce and describe Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator, a concept for realistic simulation

of healthcare scenarios in a digital sandbox environment using synthetic health data. The concept represents

a safe environment to develop, test and prepare systems and digital tools for usage in healthcare.

1 INTRODUCTION

To design effective and safe IT systems for healthcare

is a major challenge, and there is plenty of examples

of systems that have not fulfilled the goal of

facilitating provision of high-quality care (Campion-

Awwad et al., 2014; Hertzum et al., 2022). For

example, The National Programme for IT in the NHS

(NPfIT) in the UK, a large IT programme for the

public sector, was cancelled after delays, stakeholder

opposition and implementation issues (Campion-

Awwad et al., 2014). Some of the highlighted

problems with NPfIT was confidentiality and security

of patients, unreliable software and lack of

engagement with end-users (Campion-

Awwad et al., 2014). In Sweden, IT system

functionality deficiencies and lack of a standardized

infrastructure are reported to cause technostress

leading to critical incidents (Stadin et al., 2020), and

to be a barrier to innovation such as precision

medicine and developing Clinical Decision Support

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-6138-0619

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3737-3316

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6975-8520

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6564-737X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7942-2190

Systems (CDSS) (Fioretos et al., 2022;

Frisinger & Papachristou, 2023). These are all issues

that urge the importance to prepare systems for

implementation, through sufficient testing and

thought-through requirement specifications.

In the healthcare industry, safety of patients is of

highest importance. Regulations put high demands on

devices, digital tools and systems being safe to use

and free of bugs. One important step for new

innovations before entering the market is passing

clinical trials, which requires confirmed effectiveness

and safety for the patients and users. This necessitates

extensive verification and validation and access to

high quality data. There is a need to boost innovation

and speed up the development process of new

technologies and systems for healthcare, enabling

promising research to reach the market earlier, while

ensuring regulatory compliance. A new

complementary method to traditional product

development is virtual tests with simulated healthcare

processes and synthetic data. Early research shows

Apelgren, F., Seth, M., Jalo, H., Sjöqvist, B. A. and Candefjord, S.

Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care Process Simulations.

DOI: 10.5220/0013401300003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 1, pages 1127-1135

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1127

high potential for usage of synthetic data

(Chan et al., 2022; Dahmen & Cook, 2019;

Walonoski et al., 2018) and digital sandboxes

(Leckenby et al., 2021) for simulations in healthcare.

These technologies are suggested as important

building blocks for virtual testing environments.

In the Care@Distance group at Chalmers

University of Technology in Sweden, a concept and

solution for simulation and testing of digital tools for

healthcare is under development. The concept, called

Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator, has been a

stepwise process over the past 10 years, as a result of

insights from several projects and practical experiences

(Andersson Hagiwara et al., 2019; Bakidou et al.,

2023; Candefjord et al., 2024; Fhager et al., 2018; Lee

et al., 2023; Maurin Söderholm et al., 2019). It consists

of several different parts that together build a virtual

simulation environment: synthetic health data, Digital

Health Sandbox (DHS) and third-party applications.

Through Virtuality, digital systems and tools can be

tested in a safe environment, before going into real

clinical trials, implementing systems and entering the

market.

The Care@Distance group performs research on

digital solutions for healthcare, with focus on

improving the care process by introducing new CDSS

based on innovative methods and Artificial

Intelligence (AI).

By using virtual care process simulations, we

could prepare systems and tools for the clinical

environment and avoid iterating clinical trials again

when potential problems and bugs in the systems

arise. An important part of virtual care process

simulations is usage of digital health sandbox

environments, i.e. environments in which developers

can test and modify innovations in collaboration with

clinicians, adding and removing features or

combining them with other related innovations

(Ribiere & Tuggle, 2010). DHS acts as a safe-space

in which algorithms and tools for healthcare can be

tested and further developed iteratively, before tested

in the real-world clinical settings

(Leckenby et al., 2021).

For Virtuality to be useful in performing realistic

simulations, it needs to have access to relevant and

high-quality data. The demand of high-quality data

for medical and healthcare research are increasing

and the challenges with accessing those data are

highlighted by many (Kokosi & Harron, 2022;

Moniz et al., 2009; Tsao et al., 2023;

Walonoski et al., 2018). The information kept in

Electronic Health Records (EHR) is highly sensitive

and usage of real data should respect integrity,

confidentiality and security for the patients.

To avoid unnecessary use of sensitive data,

simulations on artificially generated versions of

patient health data, so-called synthetic health data, is

a suggested solution (Kokosi & Harron, 2022).

Synthetic data mimics the statistical properties of

real-world data and leaves minimal traces to the real

data (Gonzales et al., 2023). Thereby, the possibility

to link the data to individuals is low and the integrity

and safety of individuals is kept.

By connecting synthetic data with DHS and

running simulations enabled by a scenario engine

used for mimicking selected care processes,

Virtuality is a promising concept to solve above

mentioned challenges and needs. Our vision with

Virtuality is to get as close to reality as possible

without involving real patients in testing, and to

validate and simulate new IT-tools improving care

processes. In this article, we will present Virtuality,

describe its parts and motivate the usage of it by

exemplifying two different scenarios of healthcare

processes simulated in the virtual environment. Our

initial target scenarios are for time-critical patient

conditions, i.e. trauma represented by fall at home

and motor vehicle crash, and stroke, which are

important societal problems representing significant

morbidity and mortality.

2 RELATED WORK

In recent years the interest in using digital sandboxes,

synthetic data and simulation environments in the

healthcare sector have increased

(Leckenby et al., 2021; Pezoulas et al., 2024).

The approach of using a sandbox environment can

be divided into two main categories; the sandbox as a

testing environment and the sandbox as regulatory

sandbox approach (Leckenby et al., 2021). Both

categories are often focused on trial of products,

services and business models to confirm their

compliance with existing regulations before they are

implemented in real-world settings.

The concept introduced in this article, Virtuality, is

more focused on development and testing of new

services and systems in a simulated realistic setting. It

is unique in the sense that few similar technologies that

combine a digital sandbox with synthetic health data

are currently in use in a healthcare setting. One closely

related technology in use is the Blue Button Sandbox,

which uses synthetic claims data from U.S. Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), to develop and

test applications and information systems that will

need to interact with CMS data systems and Medicare

services (Gonzales et al., 2023). The Blue Button

DEMS 2025 - Special Session on Design and Evaluation of Monitoring Systems

1128

Sandbox is oriented towards development of services

that benefits Medicare enrolees, rather than being

applicable to a wider range of data, systems and

services.

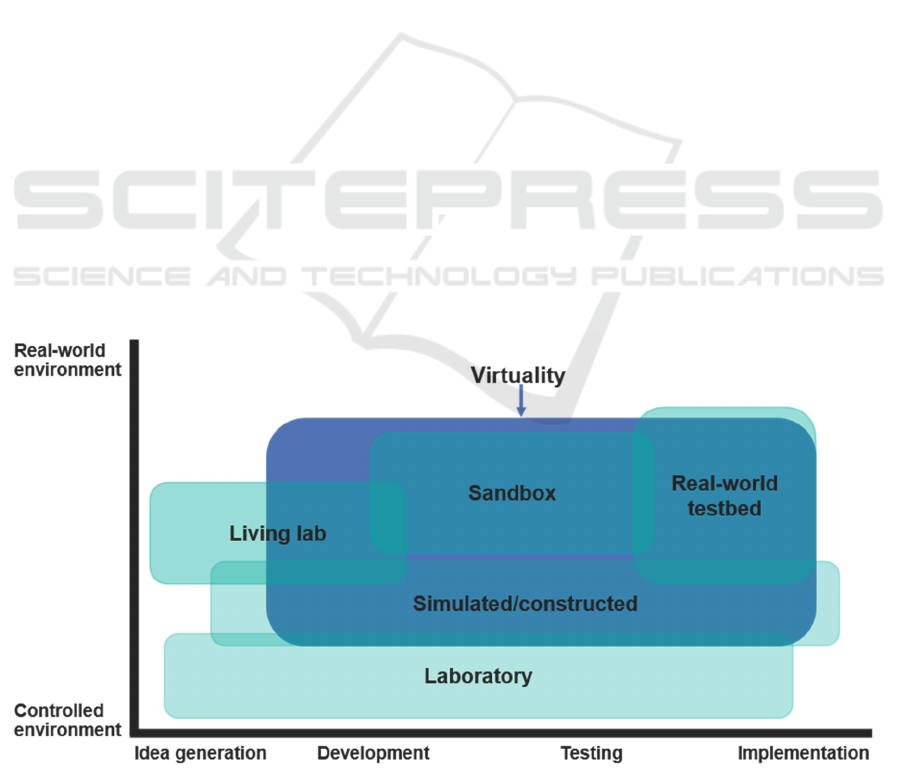

There are several different main testing

environments used for product innovation and

development of systems and tools for healthcare

(Leckenby et al., 2021). In Figure 1, we have

positioned Virtuality in relation to other testing

environments. Compared to sandboxes currently

used, Virtuality aims for a broader scope and to be

useful during a broader extent of the development

process, from idea generation to implementation.

The number of studies on synthetic health data

generation shows an increasing trend between the

years of 2015–2024 (Pezoulas et al., 2024). Synthetic

health datasets are created and used for a broad range

of use cases. Gonzales et al. (2023) summarized

current use cases as a) simulation and prediction

research, b) hypothesis, methods, and algorithm

testing, c) epidemiology/public health research,

d) health IT development, e) education and training,

f) public release of datasets, and g) linking data. The

past years, several public synthetic health datasets

have been published. Some examples of published,

publicly available synthetic health datasets and tools

for synthetic health data generation are: 1) Synthea,

generates synthetic EHRs through statistical

modelling and usage of publicly available health

statistics, clinical guidelines and protocols

(Walonoski et al., 2018), 2) SynSys, a Machine

Learning (ML)-based synthetic data generation

method for generating synthetic time series sensor

data for healthcare application

(Dahmen & Cook, 2019), 3) Medkit-Learn(ing)

Environment, a ML-based synthetic data generation

method for generating synthetic medical datasets

(Chan et al., 2022). All three above synthetic health

data generation methods and datasets are open source,

allowing developers to contribute to further

development.

The importance of conducting full-scale

simulations and their potential in prehospital care was

highlighted by Maurin Söderholm and colleagues

(Maurin Söderholm et al., 2019). By providing an

isolated and controlled environment, stakeholders can

test, validate and confirm their ideas based on

synthetic data, in order to better prepare systems for

wider implementations (Leckenby et al., 2021). This

can guide decision making and allow stakeholders to

draw conclusions comparable to those from real

clinical settings, without the immediate need to

address legal barriers.

3 CONCEPT

The Care@Distance group and collaborators are now

developing a virtual testing environment, called

Virtuality. Virtuality provides all the tools needed to

set up, configure and run realistic healthcare

simulations in isolated environments, facilitating

performing

the first two steps in the Verified

Figure 1: Positioning of Virtuality concept in relation to the main testing environments used in product innovation (adapted

from (Leckenby et al., 2021) and (Arntzen et al., 2019)).

Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care Process

Simulations

1129

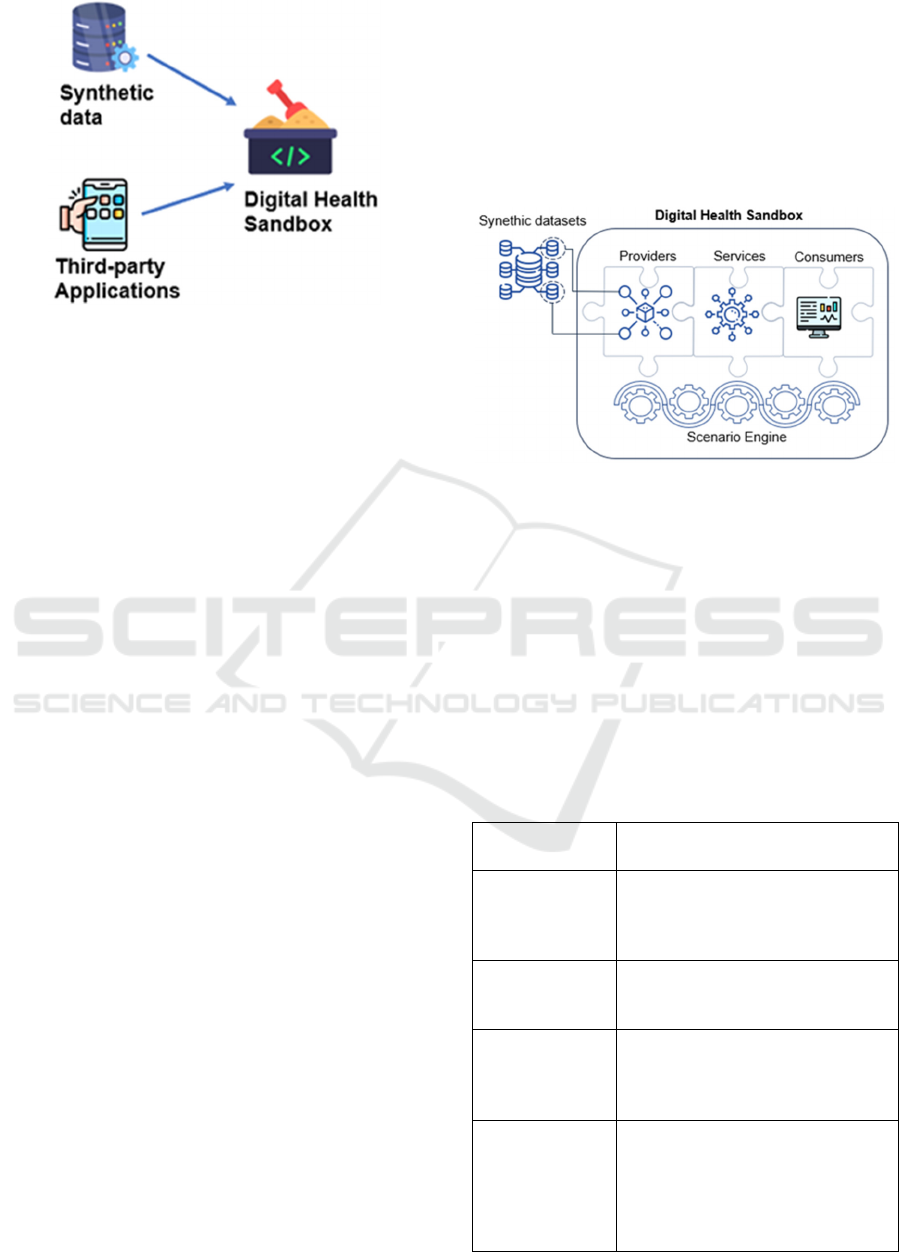

Figure 2: Virtuality consists of 1) synthetic data, 2) third-

party applications, 3) Digital Health Sandbox.

Innovation Process for Healthcare Solutions (VIPHS)

model, which corresponds to defining a prototype

(Lee et al., 2023). This includes synthetic data

generation mechanisms, access to third-party

applications and DHS, see Figure 2.

Virtuality is based on the Acute Support

Assessment and Prioritizing (ASAP) Concept. This

concept emphasizes the importance of aggregating

data from multiple sources to increase decision

precision, streamline workflows and improve patient

safety. By building the Virtuality environment around

the ASAP Concept, it ensures that interoperability

remains the central focus and foundation of all

activities within this environment.

3.1 Digital Health Sandbox

The DHS will be one of the main parts within

Virtuality, enabling effective utilization of synthetic

data and digital technologies to test and validate the

clinical utility of digital innovations, refer to Figure 2

and 3. Regardless of applications, whether it is a fall

detection system, stroke detection or trauma severity

prediction (Bakidou et al., 2023), the goal is to bridge

the gap between stakeholders, enabling clinicians,

engineers and researchers to actively participate in the

design, execution and evaluation of advanced and

realistic simulations (Maurin Söderholm et al., 2019).

The DHS is based around four core building

blocks: ASAP Providers, Services, Consumers and

the Scenario Engine. Each of these blocks, along with

their associated functionality can be seen in Table 1.

Depending on the scope and objective of the

simulation, different number of components within

each building block can be used, and various levels of

complex interaction patterns can be applied. This

means that the Graphical User Interface (GUI) also

adapts to the specific simulation scenario. For

example, in a traffic safety scenario, a user may want

to simulate how AI-algorithms and vehicle sensors

can be utilized to assess the likelihood of injuries in a

motor vehicle crash (Maurin Söderholm, 2023). In

this case, the GUI should adapt to that specific

scenario, meaning that the user should be able to

select the number of cars, car model, car occupants,

crash type, type of AI-model and type of sensor data.

Figure 3: In Virtuality, DHS can be combined with

synthetic datasets to enable realistic simulations and get full

control of the simulation scenario.

Together, the ASAP Building Blocks constitute a

comprehensive and fully customable testing arena

where any combination of devices, algorithms and

platforms can be put together to allow for realistic

simulations. The ASAP Concept supports this, by

promoting open – and standardized interoperability

interfaces, as well as synthetic data to avoid

dependencies on third-party vendors, see Figure 3.

Table 1: The DHS is composed of four building blocks:

Providers, Services, Consumers and Scenario Engine.

ASAP

Buildin

g

Block

Functionality

Providers

Devices or information providers

responsible for initiating a

simulation by sending data to ASAP

Services for further

p

rocessin

g

.

Services

Software modules responsible for

processing information coming from

ASAP Providers.

Consumers

GUI (

Graphical User Interface)

responsible for displaying

information from ASAP Services to

end users.

Scenario Engine

Orchestrator that enables the user to

determine what to simulate and how

it should be conducted, ie., decide on

the simulation scenario, what

components to be used and how they

should fit together.

DEMS 2025 - Special Session on Design and Evaluation of Monitoring Systems

1130

For instance, the synthetic data generator within

Virtuality could be used to create a fictious

smartwatch to be used within the DHS (the ASAP

Provider Building Block in Table 1). This approach

would provide immediate access to realistic data,

refer to Figure 3, eliminating delays typically caused

by dependency on third-party vendors and

applications. The Provider Building block

(smartwatch) could be integrated with an AI-based

trauma algorithm (Bakidou et al., 2023) and a third-

party EHR, represented by the ASAP Service

Building Block and Consumer Building Block,

respectively. The ASAP Concept would guide this

integration process, by specifying open – and

standardized interfaces between and within each

building block.

3.2 Synthetic Data

For the DHS to be effective and useful, data that can

act as ASAP Provider is needed. To get qualitative

real health data can be challenging and requires going

through often extensive data access applications

(Kokosi & Harron, 2022). An alternative data source

to use as ASAP Provider is synthetic data. Synthetic

data is an interesting complement to real data and has

several advantages that motivates why it is useful:

a) accelerate development processes, b) secure

patient anonymity, privacy, integrity and safety,

c) improve data accessibility, d) increase data volume

and diversity, e) account for underrepresented data

and scenarios, f) testing of not yet existing solutions,

g) address regulatory challenges in early

development without using patient data and

h) decrease dependency of data providers.

Synthetic health data can be divided into five main

categories; tabular data, image and video data, time-

series data, radionics data and multimodal

data (Pezoulas et al., 2024). The Care@Distance

group aims to create a database of synthetic data,

which can be used to run simulations on different

scenarios in the DHS. With their primary focus on

improving the prehospital care, synthetic versions of

data accessible in prehospital healthcare settings will

be the primary focus. In a prehospital setting tabular

data like EHR, image and video data of a patient or

accident site and timeseries sensor data are some of

the most interesting categories.

In addition, new data sources with the potential to

improve prehospital care are of high interest. A broad

range of parameters and different kind of data should

be available and possible to use for simulations in

Virtuality. Synthetic data can be used alone or in

combination with real data. The purpose with the

synthetic data is not to completely replace real data,

but rather to enable early verification and validation

of tools and systems before accessing real data

(Kokosi & Harron, 2022).

In a prehospital setting, for example in a motor

vehicle crash, ambulance or smart home, video data

are a promising data source. Video data in

ambulances could enable automated assessment and

informed decision-making during emergencies

(Jalo et al., 2023). To explore the use of synthetic data

and video analysis in the early characterization of

stroke-related eye movements, we generated 69

videos simulating typical eye movements seen in

stroke patients (Ollila et al., 2024). These videos

were reviewed and deemed clinically relevant by a

stroke neurologist, making them suitable for

developing CDSS. The synthetic videos were

combined with real recordings of healthy individuals

mimicking stroke-related eye movements. The use of

synthetic data resulted in creating a larger dataset,

which was crucial for models training and evaluation

to ensure strong performance.

3.3 Simulation Scenarios

In Sweden, senior citizens have been wearing social

alarms since early 1980s (Lydahl, 2024). These

alarms, consisting of a manual alarm button which

usually looks like a clock or a pendant, are frequently

used in Home Care Services (HCS) and in nursing

homes. Although these social alarms are the most

common welfare technology in the Nordic Countries

(Lydahl, 2024), an alarm from this device might be

difficult to interpret. Does the patient need acute

medical attention, or do they just need to refill a glass

of water? Since these alarms are used in both acute

and non-acute scenarios, it becomes stressful for the

personnel and can pose a danger to the patient if

critical alarms are overlooked or delayed.

Therefore, it could be valuable for the HCS to

investigate alternative setups. Perhaps combining the

social alarm with complementary information from

other sources, as in Figure 4, or analyzing the data

with AI, could give meaningful insights. For

example, if the social alarm data were accompanied

by the patient’s heart rate, angular velocities, gait

patterns and medical history, it could potentially

reveal a frail individual with a history of osteoporosis

who has experienced a fall.

This setup could potentially provide more

valuable insights, allowing the nurse to plan

appropriate interventions in a timely manner and help

in prioritizing among multiple occurring alarms. Such

simulations could be carried out within Virtuality by

Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care Process

Simulations

1131

utilizing the DHS and synthetic data, see Figure 4.

The results from the simulation could potentially lead

to an extension of current social alarm services,

enhance patient safety, and optimize care delivery.

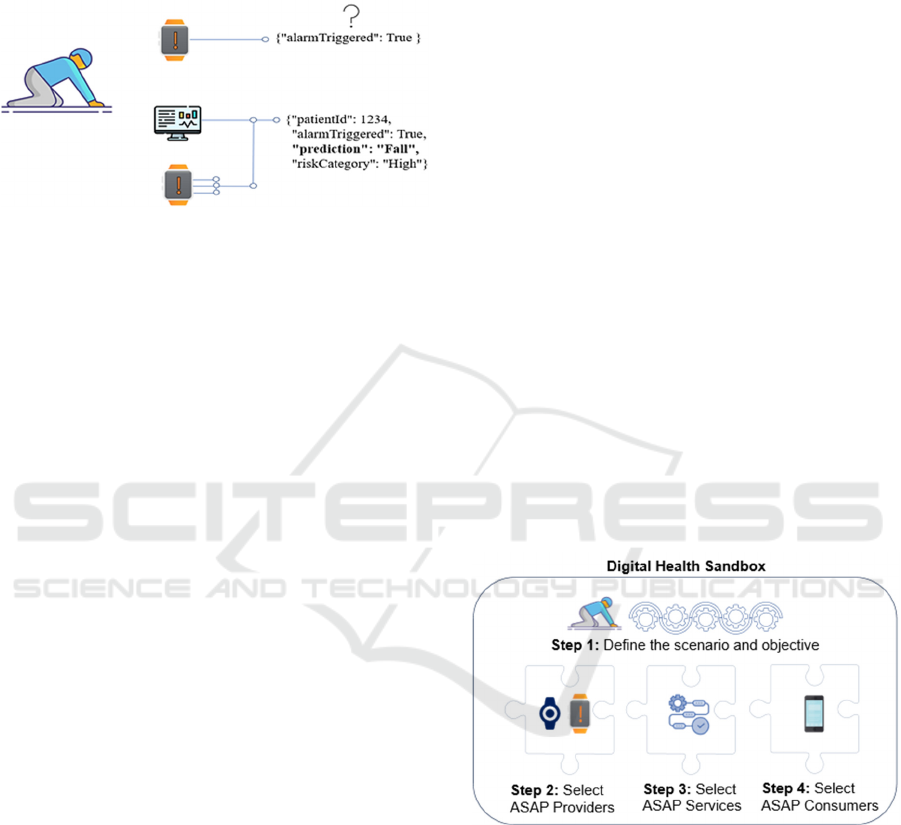

Figure 4: By aggregating data from multiple sources,

decision precision can be increased. By utilizing synthetic

data, more valuable insight could potentially be provided to

end-users during system development and tests.

Two different simulation scenarios, and how they

could be set up in Virtuality, will be described below.

Let us first assume that a user wants to investigate

new technologies and workflows to detect falls, as

alternatives or complements to the current social

alarm systems used in nursing homes. This could be

done as a realistic simulation within Virtuality,

utilizing standardized synthetic datasets together with

interoperable health applications.

The first step is to define the scope and objective

of the simulation in the DHS using the Scenario

Engine. This step is essential, as all subsequent

actions are tailored to the specific scenario. In the

case of fall detection simulations in nursing homes,

the user can start by defining a patient persona in the

Scenario Engine (step 1 in Figure 5). With just a few

clicks, a realistic but fictious elderly patient is

generated. This will create a synthetic patient profile,

including information about the patient’s age, sex,

residential address, living situation, medications and

medical history.

In the next step (step 2 in Figure 5), the user

decides what sensors to be included in the simulation.

In this scenario, the user might want to add a

smartwatch together with the social alarm as two

components in the ASAP Provider Building Block.

Based on the previously defined patient profile, the

synthetic sensor data will be dynamically generated

to ensure realistic data that accurately reflects the

patient’s characteristics.

In step 3, the user specifies how the data received

from the ASAP Providers should be processed and

managed. This step includes options for data

processing as well as data storage. For example, the

user could choose to include an AI-algorithm for

binary classification that predicts the probability of a

fall, given that the elderly have pressed the social

alarm button. This AI algorithm will be represented

as the ASAP Service Building Block in Figure 5.

In step 4, the user chooses how the output from

the algorithm will be presented to the nurses. Maybe

the nurse should be notified in a mobile app? This can

be achieved by adding the mobile app as an ASAP

Consumer Building Block. This building block

represents how and when information should be

available and presented to end users. Aspects such as

user-friendliness of the GUI can be practically tested.

Once step 1–4 in Figure 5 has been completed,

corresponding to step 1 in the VIPHS model (Lee et

al., 2023), an ASAP Pipeline has been created. The

ASAP Pipeline represents a selection of ASAP

Building Blocks which can be used for simulating the

effectiveness of the specific setup. For example, the

pipeline created in Figure 5, could be used to examine

the effectiveness of combining real-time smartwatch

data with social alarms, using a binary classification

model to predict falls among elderly at nursing

homes. A summary of the simulation process,

including a detailed description of the integration

process and its components, could be summarized in

a downloadable pdf-report. This report could act as a

recommendation or recipe for how to move this

simulation closer to clinical practice.

Figure 5: Example of a fall simulation conducted within

DHS.

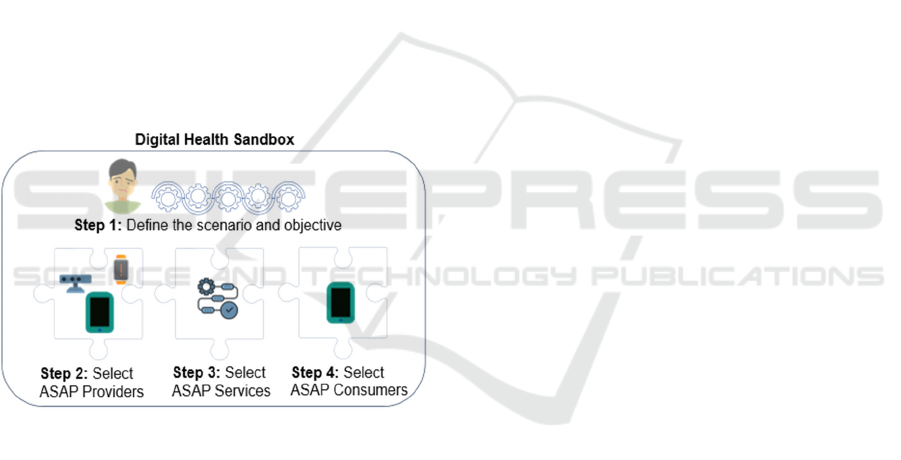

In the case of stroke, timely and accurate

assessment is critical, with subtypes like large vessel

occlusion (LVO) requiring specialized interventions

(Jalo et al., 2023). Stroke mimics, such as seizures or

migraines, can complicate the assessment, making

prehospital triage more challenging. If a user wants to

simulate how AI models and video analysis can

identify whether a patient has a stroke and

characterize the type (e.g., ischemic, hemorrhagic or

LVO) in an ambulance setting, the GUI in the DHS

DEMS 2025 - Special Session on Design and Evaluation of Monitoring Systems

1132

could adapt to support this scenario.

In step 1 in Figure 6, the user could select the

patient population to simulate, which in this case is

generating a synthetic patient exhibiting stroke

symptoms, such as facial asymmetry, abnormal eye

movements and limb paralysis.

In step 2, the user decides on which data sources

to include in the simulations such as cameras installed

in the ambulances, smartwatch, etc. as well as

configuring parameters for the prehospital

environment. In step 3, the user selects the AI models

to test their ability to identify stroke patients based on

the provided data. These models could provide

probability scores for stroke presence, subtype

classification and a recommendation for

transportation destination. In step 4, the simulation

results are tailored for end-user presentation. For

ambulance clinicians, results could be displayed on

devices commonly used in ambulances. For example,

the AI model might generate alerts indicating a high

probability of stroke, with a prediction of an LVO and

recommending transport to a comprehensive stroke

center.

Figure 6: Example of stroke simulation conducted within

DHS.

4 DISCUSSION

Virtuality connects existing tools where research has

been ongoing for several years, like digital sandboxes

and synthetic data (Chan et al., 2022;

Dahmen & Cook, 2019; Leckenby et al., 2021;

Walonoski et al., 2018), and build upon them to create

an easily accessible environment with potential to

boost healthcare innovations. The development of

Virtuality within the Care@Distance group is a result

of successful projects and observations of a rising

need for this type of solution.

As standalone tools, sandboxes and synthetic data

often require the users to do much programming

themselves to implement the available tools and

solutions. By requiring high programming

competence, we may exclude the users that possibly

would benefit the most from doing the simulations.

For example, clinicians could strongly benefit from

trying out new systems and tools in a simulated and

safe environment. Instead, by connecting the tools to

an environment that is easy to use even for non-

programmers, such as clinicians and care givers, we

introduce the possibility for a broader group to test

new systems as integrated with the current clinical

setup of systems. This can be an important step before

procurement of new systems are done, where

challenges in specifying requirements for

interoperability are common (Seth et al., 2024). The

aim with Virtuality is that a broad group of

practitioners working in the healthcare industry

should be able to use and benefit from simulating

healthcare scenarios.

Since 2016, regulatory sandboxes have been used

in the financial sector and later expanded to other

sectors

including the healthcare sector

(Leckenby et al., 2021). The introduction of Medical

Device Regulation (MDR) in Europe is welcomed to

further strengthen the safety of patients, but it has

introduced further challenges in development of new

innovative products and systems. By using sandbox

environments, exploration of processes that may

violate current rules and regulations but have

potentially large benefits if introduced into standard

practice are possible (Leckenby et al., 2021). This

enables taking one step further with innovations,

preparing them for clinical trials, motivating their

need on the market and showing the benefits they

bring. By implementing virtual testing environments

in healthcare innovation development processes, a

shortening of clinical trials is possible, resulting in a

reduction of associated costs.

There are several drawbacks with creating testing

and simulation environments that should be used by a

broad target group. First is a potential lack of

complexity in the environment. It is certainly easier

to build an environment with high complexity and

flexibility if the targeted user group has a higher

technical knowledge. The challenge will be to

balance a high complexity and flexibility of the

environment and keep it easy enough to use for users

with lower technical knowledge and skills.

Another challenge will be how to confidently

show that the created scenarios and synthetic data

used within the DHS are sufficiently realistic.

Achieving this requires a close collaboration with

clinicians, both when developing tools and concepts,

Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care Process

Simulations

1133

and while running simulations and tests in the system

(Leckenby et al., 2021). One way to confirm realism

is to run Virtuality for scenarios where the outcome is

known and compare the results.

To confirm quality and realism of the data used is

important, especially when working with synthetic

data (Chen et al., 2021). Therefore, verification and

validation of the data is an important step in the

creation process. The quality of the synthetic data is

strongly related to the methods, models and

underlying data used to create it

(Gonzales et al., 2023). We also need to be aware of

the potential risk of traces from the original data left

in the synthetic dataset, which possibly could be a risk

for the integrity and privacy of patients

(Vallevik et al., 2024). Synthetic data shows high

potential to keep the integrity, privacy and

anonymity, but still the data should be treated with

respect and carefully used. Effort needs to be put in

on choosing appropriate methods and datasets to

work with, showing the realism of the created data

and ensure that the data is disconnected from the

patients in the original dataset.

We want to emphasize that the concept described

in this article is currently on a conceptual and early-

stage level. Further work is needed before Virtuality

is ready to run at full strength and its parts sufficiently

developed and connected. This article has shown the

potential of Virtuality and its building blocks. Now

the building blocks need to be connected, and the

process simulator tried out on realistic scenarios.

Future work includes developing the DHS further and

generating synthetic datasets. The first use cases in

Virtuality will be related to the scenarios exemplified

in this article; trauma represented by fall at home and

motor vehicle crash and stroke. Later, the scenarios

used will be expanded to include other interesting

healthcare scenarios.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this article we have described Virtuality, a concept

for simulation of care processes in a safe digital

sandbox environment using synthetic health data. We

see a need and possibility to introduce this concept in

healthcare. By exemplifying two scenarios, we have

shown how Virtuality is intended to work and

motivated its potential to speed up development

processes in healthcare.

REFERENCES

Andersson Hagiwara, M., Lundberg, L., Sjöqvist, B. A., &

Maurin Söderholm, H. (2019). The Effects of

Integrated IT Support on the Prehospital Stroke

Process: Results from a Realistic Experiment. Journal

of Healthcare Informatics Research, 3(3), 300–328.

Arntzen, S., Wilcox, Z., Lee, N., Hadfield, C., & Rae, J.

(2019). Testing Innovation in the Real World.

Bakidou, A., Caragounis, E.-C., Andersson Hagiwara, M.,

Jonsson, A., Sjöqvist, B. A., & Candefjord, S. (2023).

On Scene Injury Severity Prediction (OSISP) model for

trauma developed using the Swedish Trauma Registry.

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 23(1),

206. doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02290-5

Campion-Awwad, O., Hayton, A., Smith, L., & Vuaran, M.

(2014). The National Programme for IT in the NHS: A

case study.

Candefjord, S., Andersson Hagiwara, M., Sjöqvist, B. A.,

Karlsson, J.-E., Nordanstig, A., Rosengren, L., &

Maurin Söderholm, H. (2024). Video support for

prehospital stroke consultation: Implications for system

design and clinical implementation from prehospital

simulations. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision

Making, 24(1), 146. doi.org/10.1186/s12911-024-

02539-7

Chan, A. J., Bica, I., Huyuk, A., Jarrett, D., & van der

Schaar, M. (2022). The Medkit-Learn(ing)

Environment: Medical Decision Modelling through

Simulation (No. arXiv:2106.04240). arXiv.

doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.04240

Chen, R. J., Lu, M. Y., Chen, T. Y., Williamson, D. F. K.,

& Mahmood, F. (2021). Synthetic data in machine

learning for medicine and healthcare. Nature

Biomedical Engineering, 5(6), 493–497.

Dahmen, J., & Cook, D. (2019). SynSys: A Synthetic Data

Generation System for Healthcare Applications.

Sensors, 19(5), Article 5. doi.org/10.3390/s19051181

Fioretos, T., Wirta, V., Cavelier, L., Berglund, E.,

Friedman, M., Akhras, M., Botling, J., Ehrencrona, H.,

Engstrand, L., Helenius, G., Fagerqvist, T., Gisselsson,

D., Gruvberger-Saal, S., Gyllensten, U., Heidenblad,

M., Höglund, K., Jacobsson, B., Johansson, M.,

Johansson, Å., … Rosenquist, R. (2022). Implementing

precision medicine in a regionally organized healthcare

system in Sweden. Nature Medicine, 28(10), 1980–

1982.

Frisinger, A., & Papachristou, P. (2023). The voice of

healthcare: Introducing digital decision support systems

into clinical practice - a qualitative study. BMC Primary

Care, 24(1), 67. doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02024-6

Gonzales, A., Guruswamy, G., & Smith, S. R. (2023).

Synthetic data in health care: A narrative review. PLOS

Digital Health, 2(1), e0000082.

doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000082

Hertzum, M., Ellingsen, G., & Cajander, Å. (2022).

Implementing Large-Scale Electronic Health Records:

Experiences from implementations of Epic in Denmark

and Finland. International Journal of Medical

DEMS 2025 - Special Session on Design and Evaluation of Monitoring Systems

1134

Informatics, 167, 104868.

doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2022.104868

Jalo, H., Borg, A., Thoreström, E., Larsson, N., Lorentzon,

M., Tryggvasson, O., Johansson, V., Redfors, P.,

Sjöqvist, B. A., & Candefjord, S. (2023). Early

Characterization of Stroke Using Video Analysis and

Machine Learning. Emerging Technologies in

Healthcare and Medicine, 116(116).

doi.org/10.54941/ahfe1004359

Jalo, H., Seth, M., Pikkarainen, M., Häggström, I., Jood, K.,

Bakidou, A., Sjöqvist, B. A., & Candefjord, S. (2023).

Early identification and characterisation of stroke to

support prehospital decision-making using artificial

intelligence: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open,

13(5), e069660. doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-

069660

Kokosi, T., & Harron, K. (2022). Synthetic data in medical

research. BMJ Medicine, 1(1), e000167.

doi.org/10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000167

Leckenby, E., Dawoud, D., Bouvy, J., & Jónsson, P. (2021).

The Sandbox Approach and its Potential for Use in

Health Technology Assessment: A Literature Review.

Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 19(6),

857–869.

Lee, E., Sjöqvist, B. A., Andersson Hagiwara, M., Maurin

Söderholm, H., & Candefjord, S. (2023). Development

of Verified Innovation Process for Healthcare Solutions

(VIPHS): A Stepwise Model for Digital Health. Studies

in Health Technology and Informatics.

doi.org/10.3233/SHTI230250

Lydahl, D. (2024). Good care and adverse effects:

Exploring the use of social alarms in care for older

people in Sweden. Health, 28(4), 559–577.

Maurin Söderholm, H. (2023, March). TEAPaN 1 SoSSUM

- Traffic Event Assessment, Prioritizing and

Notification. https://www.vinnova.se/en/p/teapan-1-

sossum---traffic-event-assessment-prioritizing-and-

notification-steg1-simulations-and-demonstrators/

Maurin Söderholm, H., Andersson, H., Andersson

Hagiwara, M., Backlund, P., Bergman, J., Lundberg, L.,

& Sjöqvist, B. A. (2019). Research challenges in

prehospital care: The need for a simulation-based

prehospital research laboratory. Advances in

Simulation, 4(1), 3. doi.org/10.1186/s41077-019-0090-

0

Moniz, L., Buczak, A. L., Hung, L., Babin, S., Dorko, M.,

& Lombardo, J. (2009). Construction and Validation of

Synthetic Electronic Medical Records. Online Journal

of Public Health Informatics, 1(1).

doi.org/10.5210/ojphi.v1i1.2720

Ollila, S., Ström, E., Khatiri, R., Svensson, T., &

Westerberg, J. (2024). Tidig karaktärisering av stroke

genom videoanalys, maskininlärning och

ögonspårning.

http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12380/308310

Pezoulas, V. C., Zaridis, D. I., Mylona, E., Androutsos, C.,

Apostolidis, K., Tachos, N. S., & Fotiadis, D. I. (2024).

Synthetic data generation methods in healthcare: A

review on open-source tools and methods.

Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal,

23, 2892–2910.

Ribiere, V. M., & Tuggle, F. D. (Doug). (2010). Fostering

innovation with KM 2.0. VINE, 40(1), 90–101.

Seth, M., Jalo, H., Lee, E., Bakidou, A., Medin, O., Björner,

U., Sjöqvist, B. A., & Candefjord, S. (2024). Reviewing

Challenges in Specifying Interoperability Requirement

in Procurement of Health Information Systems. Studies

in Health Technology and Informatics.

doi.org/10.3233/SHTI230917

Stadin, M., Nordin, M., Fransson, E. I., & Broström, A.

(2020). Healthcare managers’ experiences of

technostress and the actions they take to handle it – a

critical incident analysis. BMC Medical Informatics

and Decision Making, 20(1), 244.

doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01261-4

Tsao, S.-F., Sharma, K., Noor, H., Forster, A., & Chen, H.

(2023). Health Synthetic Data to Enable Health

Learning System and Innovation: A Scoping Review.

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics.

doi.org/10.3233/SHTI230063

Vallevik, V. B., Babic, A., Marshall, S. E., Elvatun, S.,

Brøgger, H. M. B., Alagaratnam, S., Edwin, B.,

Veeraragavan, N. R., Befring, A. K., & Nygård, J. F.

(2024). Can I trust my fake data—A comprehensive

quality assessment framework for synthetic tabular data

in healthcare. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 185, 105413.

doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105413

Walonoski, J., Kramer, M., Nichols, J., Quina, A., Moesel,

C., Hall, D., Duffett, C., Dube, K., Gallagher, T., &

McLachlan, S. (2018). Synthea: An approach, method,

and software mechanism for generating synthetic

patients and the synthetic electronic health care record.

Journal of the American Medical Informatics

Association, 25(3), 230–238.

Introducing Virtuality - Virtual Care Process Simulator: A Concept Utilizing Synthetic Data and a Digital Health Sandbox for Care Process

Simulations

1135