Exploring the EarMetrics Concept: The Bony Ear Canal as a

Non-Pigmented Site for Photoplethysmography

David Western

1 a

, John Eveness

1

, Beshoy Agayby

2 b

, Xicai (Alex) Yue

1 c

, Timothy Cox

1 d

,

Alistair Foster

2

and Nick Gompertz

2 e

1

Institute of BioSensing Technology, UWE Bristol, Bristol, U.K.

2

Earswitch Ltd, U.K.

{David.Western, John.Eveness, Alex.Yue, Timothy.Cox}@uwe.ac.uk, {beshoy, alistair, nick}@earswitch.co.uk

Keywords:

Photoplethysmography, Pulse Oximetry, Ear Canal, Skin Tone, Earables.

Abstract:

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is a well-established form of physiological sensing, but persistent challenges

include skin-tone-dependent variations in performance and trade-offs between performance and acceptance

factors in site selection. We propose that the inner, bony portion of the ear canal may offer several advantages

over established sites, including reduced sensitivity to skin tone. We support this position through a combi-

nation of anatomical analysis, colorimetry, and the first examples of PPG data collected from the bony ear

canal, including pulse oximetry calculations during voluntary breathholds. Colorimetry revealed no statisti-

cally significant differences in lightness, chroma, or hue of the bony canal between subjects with lighter versus

darker external skin tones. The commonly used ratio-of-ratios (R) method for pulse oximetry was sensitive to

de-oxygenation from breathholds, showing statistically significant correlation with breathhold duration. Our

results show that the bony ear canal is not pigmented, and that PPG signals can be obtained from this site, even

in the presence of idiosyncracies such as earwax and myringosclerosis.

1 INTRODUCTION

Photoplethysmography (PPG) is a well-established

form of physiological sensing. It is widely used for

measurements including heart rate, pulse oximetry,

and - increasingly - blood pressure, due to advan-

tages such as its low cost, ease of miniaturisation,

and richness of information content. However, per-

sistent challenges include skin-tone-dependent vari-

ations in performance (Nowara et al., 2020; Martin

et al., 2024), movement artefact (Ismail et al., 2021),

and the trade-offs between performance and accep-

tance factors in site selection (Seifi et al., 2018; Long-

more et al., 2019).

Numerous prior works have demonstrated the po-

tential of the ear canal as a site for PPG sensing, but

in virtually all cases the focus has been on the outer,

cartilagenous portion of the canal. In this paper, we

propose that the inner, bony portion of the ear canal

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4303-7423

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6205-5846

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1419-825X

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9200-9525

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6896-0441

may offer several advantages over the cartilagenous

portion, including reduced sensitivity to skin tone. We

provide evidence to support these assertions through

a combination of anatomical analysis, colorimetry,

and the first examples of PPG data collected from the

bony ear canal, including pulse oximetry calculations

during voluntary breatholds.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Photoplethysmography (PPG)

2.1.1 Basic Principles

PPG is a non-invasive optical technique that measures

blood volume changes in the microvascular bed of

tissue. It is based on the principle that light absorp-

tion by blood is different from that of surrounding tis-

sue, and that the absorption varies with the volume

of blood in the illuminated area. When light is shone

on the skin, some of it is absorbed by the underly-

ing tissue, and some portion of the unabsorbed light

can be detected by a photodetector. PPG devices are

Western, D., Eveness, J., Agayby, B., Yue, X. A., Cox, T., Foster, A. and Gompertz, N.

Exploring the EarMetrics Concept: The Bony Ear Canal as a Non-Pigmented Site for Photoplethysmography.

DOI: 10.5220/0013401600003911

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2025) - Volume 2: HEALTHINF, pages 1045-1052

ISBN: 978-989-758-731-3; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

1045

typically categorised as ‘transmission’ or ‘reflection’

devices, depending on whether the light source and

photodetector are on opposite sides of the tissue or on

the same side. Most PPG devices make use of light

sources and one or more photodetectors in direct con-

tact with the skin. However, it is also possible to cap-

ture PPG signals remotely, often using ambient light

sources, cameras, and advanced algorithms to focus

the measurement on a suitable region-of-interest, as

recently reviewed by Pirzada et al. (2024).

Arguably the most common application of PPG is

heart-rate monitoring, where the pulsatile component

of the signal is used to detect the heart rate. PPG sig-

nals can also be used to estimate other physiological

parameters, such as blood pressure, respiratory rate,

and oxygen saturation.

2.1.2 Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a specific application of PPG that

measures the oxygen saturation of arterial blood. It

is based on the principle that oxygenated and deoxy-

genated blood have different absorption spectra as a

function of wavelength, and that the ratio of these two

components can be used to calculate the oxygen satu-

ration of the blood. Pulse oximetry is widely used in

clinical settings, and is also increasingly being used in

consumer devices for continuous health monitoring.

The most common method for calculating oxy-

gen saturation from PPG signals is the ratio-of-ratios

method, using PPG signals captured at two different

wavelengths of light, typically red (e.g. 640 nm) and

infrared (e.g. 940 nm) (Nitzan et al., 2020). These

two signals are each decomposed into a pulsatile ‘AC’

component and a non-pulsatile ‘DC’ component. The

AC/DC ratio is then calculated for each wavelength,

and the ratio of these two ratios is used as a proxy for

oxygen saturation, which can be determined from a

device-specific calibration curve.

In recent years there has been increasing evidence

of racial bias in pulse oximetry, with darker-skinned

individuals being more likely to be victims of ‘oc-

cult hypoxaemia’, in which blood oxygenation is low

enough to warrant clinical attention but the oxime-

ter indicates a reading within healthy bounds (Sjoding

et al., 2020; Nowara et al., 2020; Martin et al., 2024).

2.1.3 In-Ear PPG

Various studies from as early as 2007 (Vogel et al.,

2007) have demonstrated the potential of the ear canal

as a site for PPG sensing. As reviewed by Azudin

et al. (2023), potential advantages include ease of in-

tegration with earbud devices, robustness to periph-

eral blood perfusion changes (e.g. in hypothermia),

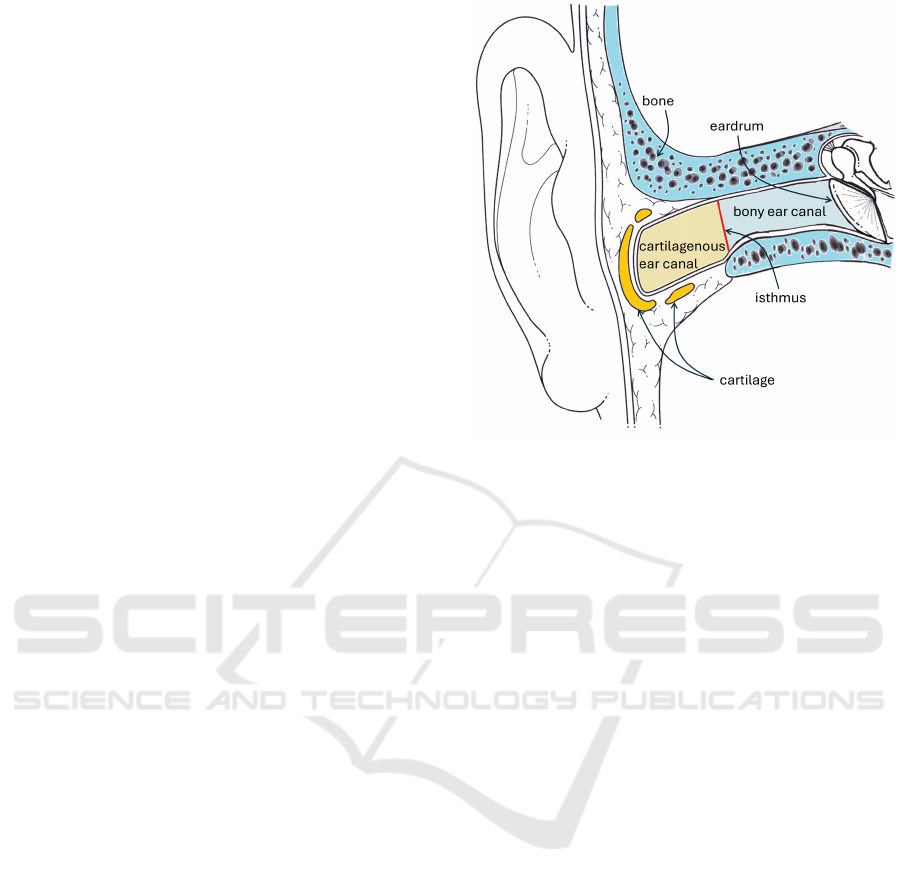

Figure 1: A cross-sectional drawing of the ear canal. The

outer third can be seen to be surrounded by cartilagenous

tissue, while the inner two thirds is surrounded by bone.

Adapted from Descouens (2009).

reduced exposure to changing environmental vari-

ables (e.g. ambient light and temperature), and re-

duced motion artefact.

Prior in-ear devices typically focus on the external

ear (e.g. concha or tragus) or the cartilagenous outer

third of the ear canal (Azudin et al., 2023). However,

we propose that a stand-off sensor targeting the inner,

bony portion of the ear canal, rather than the outer car-

tilagenous portion, can offer distinctive advantages.

2.2 Anatomy of the Ear Canal

The ear canal (external auditory meatus) is divided

into two portions: the outer, cartilagenous portion,

and the inner, bony portion. The bony-cartilagenous

junction is at the isthmus, the narrowest part of the

canal, positioned approximately one third of the dis-

tance from the outer opening to the eardrum (Stinson

and Lawton, 1989). The cartilagenous portion is the

outer third of the canal, and produces hairs and ceru-

men (earwax), which the bony portion does not. Fur-

thermore, it is tacit knowledge among many physi-

cians that the bony ear canal is not pigmented, while

the cartilagenous portion is. However, we are not

aware of any published work that confirms this, prior

to the evidence provided in this paper.

The skin lining the bony ear canal is much thin-

ner that that of the cartilagenous portion: approxi-

mately 0.1 mm vs. 1.0-1.5 mm respectively (Perry

and Shelley, 1955). This thinner medium may of-

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1046

fer improved inter-individual repeatability by reduc-

ing wavelength-dependent variations in path length.

Simulations by Ash et al. (2017) demonstrate that the

relative intensity of light penetrating to a depth of

1mm increases by an order of magnitude as wave-

length increases across the visible and near-infrared

spectrum. Thus the effective path length from light

source to sensor is dependent on both wavelength

and the relative configuration of source, sensor, and

anatomy. Device-specific calibration curves are typi-

cally used to account for this, but cannot compensate

for inter-subject anatomical variations (Yossef Hay

et al., 2018; Moc¸o et al., 2016). In the thinner skin

of the bony ear canal, although much of the light

may penetrate into the underlying bone, the absorp-

tion coefficient of bone is relatively consistent across

the visible and near-infrared spectrum (Genina et al.,

2008). Hence we propose that greater consistency of

path lengths between wavelengths may result in re-

duced inter-individual variations in calibration curves

for a device targeting the bony ear canal compared

with fleshier sites.

3 EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

In this section we describe experiments conducted to

provide proof-of-concept for bony ear canal as a vi-

able site for pulse oximetry.

3.1 Cohort

We set out to recruit a cohort of healthy adult vol-

unteers with a range of skin tones, as measured by

the Fitzpatrick scale. This scale is a widely used

classification system for human skin colour, based on

the skin’s appearance and response to sun exposure.

Although it has recognised limitations (Monk, 2023;

Tian, 2024), suitable alternatives were not well estab-

lished at the start of our study, and it allows our work

to be easily compared with prior art, in which it is

used widely. Prospective participants were excluded

if they had any known history of circulatory disorder

such as Raynaud’s Syndrome, thrombosis, hyperten-

sion, or heart disease.

Thirty-three subjects were recruited from the gen-

eral population after pre-screening based on self-

assessment of skin-tone against the Fitzpatrick scale

to ensure broad representation. Of these, two subjects

were excluded due to excessive earwax in both ears,

to conservatively avoid the risk of study instruments

compacting the wax against the eardrum.

As shown in Fig. 3, the cohort was well-

distributed across the Fitzpatrick scale. Although

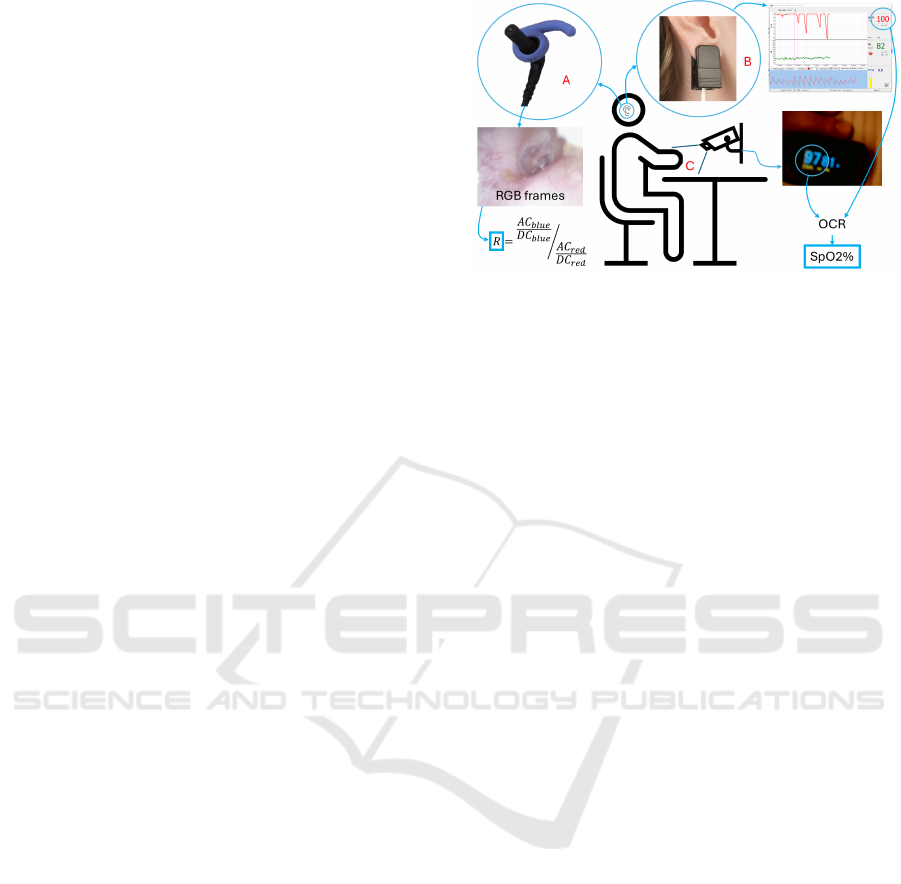

Figure 2: The configuration of equipment used in this study.

A = Prototype EarMetrics

®

device, which was positioned in-

side the ear canal, capturing RGB images at 30 frames-per-

second (fps). B = Earlobe pulse oximeter, transmitting data

via bluetooth to the experiment manufacturer’s Oximeter

Manager software, from which screenshots were captured

at 1 fps. C = Finger pulse oximeter, monitored by a camera

mounted above the hand at 1 fps. For B and C, optical char-

acter recognition (OCR) software was used to extract SpO2

values.

none of our participants self-identified as Fitzpatrick

type VI (the darkest category), we were able to re-

cruit participants from all other types, including ten

from type V.

3.2 Equipment

The configuration of equipment used in this study is

shown in Fig. 2.

3.2.1 EarMetrics

®

The in-ear sensor used in this study is a prototype

EarMetrics

®

device, developed by Earswitch Ltd. The

concept of non-contact, stand-off or remote spec-

troscopy (including PPG) from the inner ear canal

has been termed EarMetrics

®

and has patent granted

(UK) (Gompertz, 2023) and pending internationally

by EarSwitch Ltd. The EarMetrics concept devel-

oped from the EarSwitch concept, in which detection

of ear-drum movement mediated by voluntary control

of middle ear muscles is used as an assistive switch

for individuals with motor neurodisabilities, includ-

ing motor neurone disease (MND/ALS) (Hoyle et al.,

2024). The EarMetrics experimental device studied

consisted of CMOS camera module with 4 white light

LEDs mounted within a cylindrical metal barrel. The

CMOS camera module was mounted in a 3D printed

barrel component, within an adjustable ear worn de-

vice allowing alteration of angle and depth of the

camera module within the wearers ear-canal. Soft

elastomer outer earbud components were provided to

Exploring the EarMetrics Concept: The Bony Ear Canal as a Non-Pigmented Site for Photoplethysmography

1047

fit the individual in small/medium/large and left/right

configurations.

The EarMetrics camera module was wired to a

MIPI-to-USB conversion PCB. This was plugged via

USB cable to the research laptop for data acquisition.

The data from the CMOS camera was collected on the

research laptop synchronously with the data recording

from the reference devices.

3.2.2 Reference Devices

For comparison with the EarMetrics device, we used

two reference devices approved for medical use. Data

from both devices was captured using the same exper-

iment PC using custom software in order to synchro-

nise the data streams.

• Finger: a Creative PC-60B1 finger oximeter was

worn on the index finger of the right hand. Read-

ings were captured using a camera connected via

USB to the experiment computer and mounted

over the hand, facing the on-device display. Cap-

tured frames were timestamped by our custom

software, and the SpO2 and pulse rate values were

extracted from the display using optical character

recognition (OCR).

• Earlobe: a Creative SP-20 pulse oximeter was

worn on either the left or right earlobe (chosen

to avoid interference with the EarMetrics device

and any jewellery). Readings were transmitted

wirelessly to the experiment computer via Blue-

tooth and displayed using the manufacturer’s soft-

ware, such that screenshots could be captured and

timestamped by our custom software. Readings

were extracted by application of optical character

recognition to relevant sections of these screen-

shots.

This approach enabled efficient, approximately

synchronised data capture from multiple conventional

devices. The accuracy of synchronisation is depen-

dent on the lag in each device between signal acquisi-

tion and display/transmission. Informal experiments

with deliberately induced motion artefacts (tapping

the sensors) indicated that these delays were consis-

tently less than 3 seconds, hence only time differences

greater than this may be considered non-negligible.

3.3 Protocol

Each participant sat in a chair as the devices were ap-

plied. They were then allowed five minutes of set-

tling time, making slow movements of their head and

hands to ensure comfort and stability of the devices.

Next, they performed four breathholds, each lasting

as long as they could manage without excessive dis-

comfort. The first and third were performed after in-

haling (i.e. with lungs full) and the second and fourth

after exhaling (i.e. with lungs empty). In each case,

the researcher provided a 10-second countdown after

which the the participant began the breathhold at the

next appropriate point in their breathing cycle. The

researcher used a button in the custom software in-

terface to approximately timestamp the start and end

of each breathhold based on visual observation. A

minimum of 60 seconds was allowed between breath-

holds to allow the participant to recover; a previous

study with finger and in-ear oximetry during breath-

holds (Davies et al., 2020) provides evidence that this

is sufficient for SpO2 levels to return to baseline, and

this was corroborated in our own data.

3.4 Analysis

3.4.1 Colorimetry

To test the conjecture that the bony ear canal is not

substantially pigmented, we extracted a frame from

the end of the settling period (before breathholds) for

each participant. An arbitrary pixel was manually se-

lected from the canal wall, near the tympanic mem-

brane (to conservatively avoid the cartilagenous outer

canal), avoiding visually apparent blood vessels. The

brightness values of the three colour channels (RGB)

were extracted and converted to the CIELAB-based

‘LCh’ colour space for more perceptually uniform

interpretation (Weatherall and Coombs, 1992; Tian,

2024). In this space, L* represents lightness, C* rep-

resents chroma (saturation), and h* represents hue.

3.4.2 Oximetry

Custom software was used to extract mean RGB

brightness values (three colour channels) across all

pixels of each frame from the EarMetrics

®

device.

The specific parameters of this algorithm were de-

termined heuristically to optimise visually perceived

signal quality and robustness to artefacts. Each of

the three resulting time series was split into AC (pul-

satile) and DC (baseline) components by applying

a 10th-order zero-phase Butterworth highpass filter

with a cut-off frequency of 0.25 Hz, then subtracting

this highpass-filtered signal from the original to ob-

tain the DC signal. The high-pass filtered signal was

low-pass filtered at 8 Hz to remove high-frequency

noise. Peaks were detected in this signal to identify

individual heartbeats. To exclude sections corrupted

by artefact, beats of abnormal length were excluded

using the following heuristically determined thresh-

olds: < 50% or > 150% of median beat interval, or

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1048

Figure 3: Images captured using the EarMetrics

®

device

showing the ear canal of participants. The precise field

of view and light distribution vary between participants.

Hence, the cartilagenous outer ear canal may be visible in

outer portions of some images, evidenced by the presence

of hair and/or cerumen. The tympanic membrane is seen as

a dark central region in most images. The canal wall sur-

rounding this is considered to be the bony ear canal.

< 80% or > 120% of the previous interval. The AC

signal was then calculated as the peak-to-peak ampli-

tude of the high-pass filtered signal within each valid

beat. The ‘ratio-of-ratios’ R was then calculated as

the ratio of the AC/DC values between the blue and

red channels, providing an uncalibrated proxy mea-

sure of SpO2. No R values were calculated for abnor-

mal beats, identified as described above.

For each breathhold, the resting value of R (for the

EarMetrics

®

device) or SpO2 (for the reference de-

vices) was calculated as the median in the window

from 15 to 5 seconds before the start of the breath-

hold. The depleted value was calculated as the min-

imum in the window from 20 seconds before to 30

seconds after the end of the breathhold. The effect

of the breathhold was calculated as the difference be-

tween the depleted and resting values.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Pigmentation of the Bony Ear Canal

As shown in Fig. 4, the LCh values sampled from the

bony ear canal portions of the sample images in Fig. 3

show no clear separation by external skin tone. For

statistical analysis, Fitzpatrick scales I-III and IV-V

were combined to form two groups. Two-tailed het-

eroscedastic T-tests were performed to compare the

L*, C*, and h* values between these groups, reveal-

ing no statistically significant differences (p > 0.1).

Figure 4: Colorimetry values sampled from the bony ear

canal (images presented in Fig. 3) show no clear separa-

tion by external skin tone (Fitzpatrick scale, colour coded

as shown in the legend). The 3-dimensional LCh colour

space is represented across two 2-dimensional scatter plots.

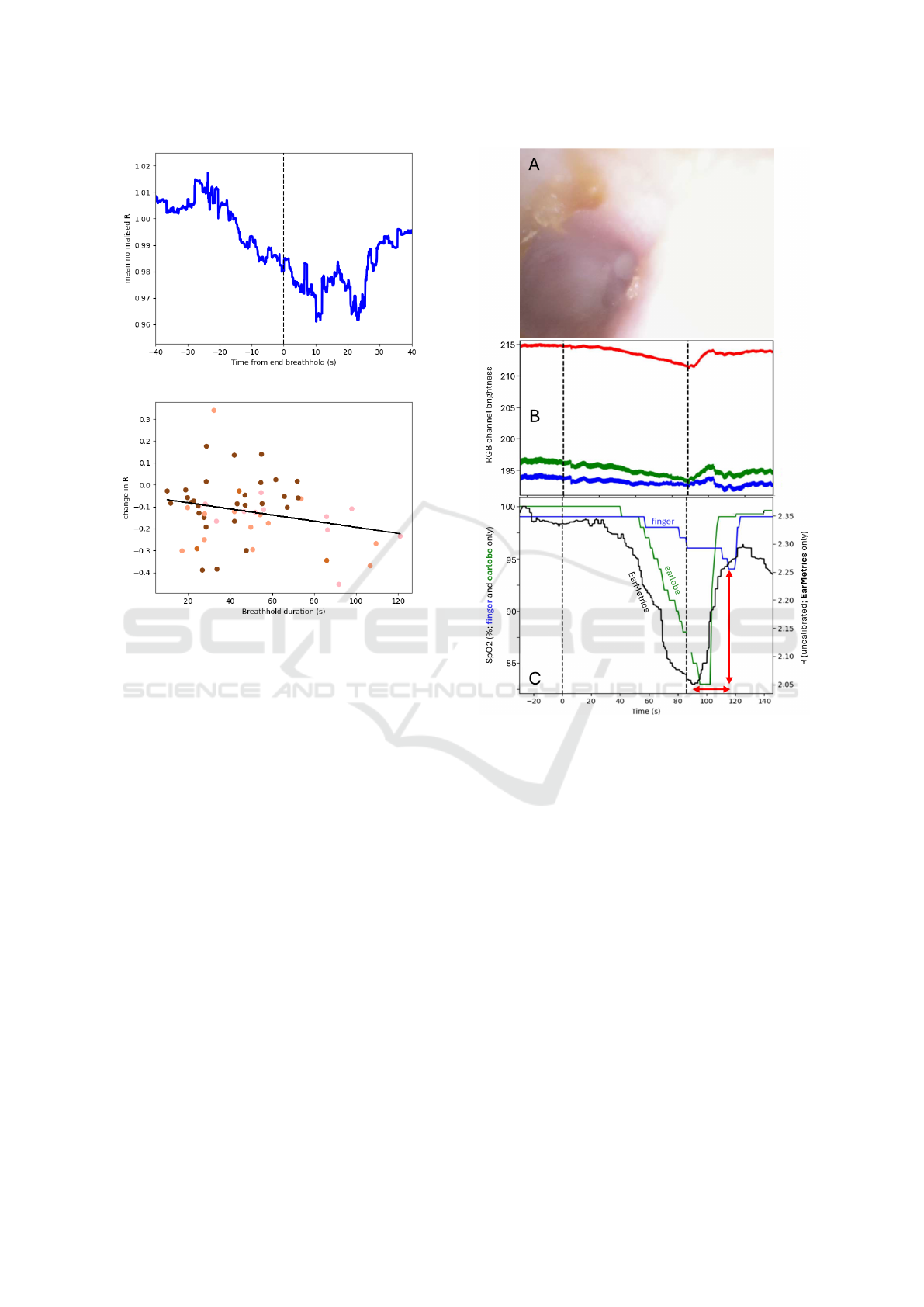

4.2 Example Breathhold Data

As shown in Fig. 5, the R metric from the

EarMetrics

®

device is sensitive to changes in oxygen

saturation during breathholds. Although the dura-

tion of breathhold and the extent of de-oxygenation

vary substantially between participants, there is a

statistically significant correlation between the two

(R

2

= 0.06, p = 0.015). Fig. 6 shows an example

of the data collected from a single participant during

a breathhold. The R value from EarMetrics

®

device

shows a clear response to the breathhold, and appear

to descend earlier and begin to recover earlier than the

SpO2 values from the reference devices.

5 DISCUSSION

From the presented results, we draw the following key

insights:

• The bony ear canal is not pigmented (Fig. 3,

Fig. 4). It may therefore offer a more equitable

target site for PPG sensing. Limited other non-

pigmented external sites exist, such as the nail

beds or the lips, but these are less conveniently

accessible, especially for continuous monitoring.

Exploring the EarMetrics Concept: The Bony Ear Canal as a Non-Pigmented Site for Photoplethysmography

1049

Figure 5: Upper panel: The normalised R value from the

EarMetrics

®

device across all breathholds from all subjects,

synchronised to the end of the breathhold. Lower panel:

The change in R (depleted - baseline) was significantly cor-

related with the breathhold duration (R

2

= 0.07, p = 0.029).

Data points are coloured according to the subject’s Fitz-

patrick skin type.

• Pulse oximetry at this site is sensitive to de-

oxygenation from breathholds (Fig. 5), and may

offer insights distinctive from the more commonly

targeted outer portion of the ear canal, owing to

the difference in vascularization and skin thick-

ness (Section 2.2). The delayed and muted re-

sponse of the finger device relative to the ear-

lobe is consisent with observations in prior studies

(Lindholm et al., 2007), and is attributable to the

greater distance between the finger and the heart.

The earlier response of the EarMetrics

®

device

(Fig. 6) is possibly indicative of a more central

blood supply, as described in Section 2.2, or pro-

tection from effects of vascular autonomic func-

tion or peripheral vasoconstriction. Hence it is

possible that pulse oximetry from the bony ear

canal may provide advantages in the speed of re-

sponse to changes in central blood oxygenation,

e.g. during apnoeic episodes.

Figure 6: Example data from a single participant dur-

ing a breathhold. Panel A shows a single frame captured

from the EarMetrics

®

device; in which several idiosyncra-

cies are apparent: presence of earwax, myringosclerosis

(white patches on the eardrum), and wide variation in light

distribution. Panel B shows the average channel brightness

in each of the three colour channels (red, green, blue) across

all frames. Dashed vertical lines indicate the start and end of

the breathhold. Pulse waveform (i.e. AC) amplitude is dis-

cernible from the thickness of the lines. Variations in both

AC and DC components are apparent during the breath-

hold. Respiratory frequency oscillations are visible even

during the breathhold, reflecting ongoing autonomic fluctu-

ations modulating cardiovascular properties as observed in

prior studies (Western, 2012; Hanson et al., 2012). Panel

C shows the variations in SpO2 readings from the refer-

ence devices (left vertical axis) and the R metric (uncali-

brated SpO2 proxy) from the EarMetrics device (right ver-

tical axis). As highlighted by the red arrows, EarMetrics

readings appears to descend earlier and begin to recover ear-

lier than the SpO2 values from the reference devices, and

the finger sensor is relatively insensitive to the transient de-

oxygenation.

• PPG signals can be obtained from the bony ear

canal, even in the presence of idiosyncracies such

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1050

as earwax and myringosclerosis (Fig. 6). Al-

though a small number of participants were ex-

cluded from our study due to earwax, in deploy-

ment the device may be usable with only occa-

sional or one-off removal of earwax.

The above insights warrant further development

and evaluation of the EarMetrics

®

concept. How-

ever, several limitations of the current study should

be noted:

• The use of breathholds yields only transient

changes in oxygen saturation and presents sub-

stantial inter-subject variability, for example in the

duration of voluntary breathholds. As can be seen

in Fig. 5, our dataset lacked examples of partici-

pants with darker skin tones (Fitzpatrick type IV-

V) achieving long breathholds (> 70 seconds) and

the associated substantial de-oxygenation. Fur-

thermore, the physical response (e.g. gasping) to

resumption of breathing presents challenging con-

ditions for the extraction of clean PPG signals dur-

ing the brief peak in de-oxygenation. More rig-

orous experiments could be achieved by using a

controlled hypoxia chamber, using a rebreathing

apparatus to induce more consistent and substan-

tial de-oxygenation, or working with participants

with chronic deoxygenation confirmed by gold-

standard methods.

• The reference devices used have notable limita-

tions in accuracy (Olive et al., 2016). They are

both likely to perform differently for different skin

tones. Furthermore, although the finger site is

typically less pigmented than the earlobe, its dis-

tal location makes it less responsive to transient

changes in central blood oxygenation (Lindholm

et al., 2007). The gold standard for SpO2 mea-

surement is arterial blood gas analysis, which is

invasive and impractical for repeated measure-

ments except where dictated by clinical necessity.

• The colorimetric measurements were taken from

the EarMetrics

®

device itself, rather than from a

dedicated colorimeter, which might offer more

optimal lighting and calibrated sensing, but may

not be suitable for targetting the bony ear canal.

A single pixel was sampled from each image, but

in further work a larger sample could be taken to

account for variations in anatomy and lighting.

• Our study made use of the Fitzpatrick scale as a

proxy for skin tone, which has recognised limita-

tions in its suitability for capturing the full breadth

of human skin tones. Future work should con-

sider more sophisticated methods for character-

ising skin tone, such as the recently developed

Monk Skin Tone Scale (Monk, 2023).

• Despite proactive recruitment, our cohort did not

include any participants self-identifying as Fitz-

patrick type VI, the darkest category. Nonethe-

less, the second darkest category, type V, included

more participants than any other.

• PPG signals were extracted from the full frames

captured by the EarMetrics device. Performance

could be improved through more sophisticated

signal processing or computer vision techniques

to focus on the most informative regions of the

image and focus more exclusively on the bony ear

canal.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper provides evidence to support anecdotal

accounts that skin in the human bony ear canal is

not pigmented; colorimetric analysis showed no sta-

tistically significant differences in lightness, chroma,

or hue of the bony ear canal between subjects with

lighter versus darker external skin tones. It should

therefore be considered as a target site for optical

sensing modalities, such as photoplethysmography

(PPG), that are sensitive to the variable influence of

pigmentation. We further support this position with

evidence that clear PPG signals can be obtained from

this target site, even in the presence of idiosyncracies

such as earwax and myringosclerosis. Pulse oximetry

at this site is sensitive to de-oxygenation from breath-

holds, as indicated by the statistically significant cor-

relation with breathhold duration. This site may offer

insights distinctive from the more commonly targeted

outer portion of the ear canal, owing to the difference

in vascularization.

Further work should be conducted to evaluate the

potential of the bony ear canal as a racially equitable,

sensitive, reliable, and convenient target site for pulse

oximetry and other physiological sensing. This work

should include validation against gold-standard arte-

rial blood gas analysis and evaluation of user accep-

tance for both long-term usage and acute monitoring

applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Innovate UK grant num-

ber 10027966, and is co-authored by members of Ear-

switch Ltd, a company that is commercialising the

EarMetrics

®

concept.

Exploring the EarMetrics Concept: The Bony Ear Canal as a Non-Pigmented Site for Photoplethysmography

1051

REFERENCES

Ash, C., Dubec, M., Donne, K., and Bashford, T. (2017).

Effect of wavelength and beam width on penetration

in light-tissue interaction using computational meth-

ods. Lasers in Medical Science, 32(8):1909–1918.

Azudin, K., Gan, K. B., Jaafar, R., and Ja’afar, M. H.

(2023). The Principles of Hearable Photoplethys-

mography Analysis and Applications in Physiological

Monitoring–A Review. Sensors, 23(14):6484.

Davies, H. J., Williams, I., Peters, N. S., and Mandic, D. P.

(2020). In-Ear SpO2: A Tool for Wearable, Unob-

trusive Monitoring of Core Blood Oxygen Saturation.

Sensors, 20(17):4879.

Descouens, D. (2009). Oreille-Audition.jpg.

Genina, E. A., Bashkatov, A. N., and Tuchin, V. V. (2008).

Optical Clearing of Cranial Bone. Advances in Opti-

cal Technologies, 2008(1):267867.

Gompertz, N. (2023). An apparatus and method for captur-

ing biometric data from a human or other animal.

Hanson, B., Western, D., Gilbey, M. P., Bostock, J., Boyett,

M. R., Zhang, H., Coronel, R., and Taggart, P. (2012).

Cyclical Modulation of Human Ventricular Repolar-

ization by Respiration. Frontiers in Cardiac Electro-

physiology, 3:379.

Hoyle, A. C., Stevenson, R., Leonhardt, M., Gillett, T.,

Martinez-Hernandez, U., Gompertz, N., Clarke, C.,

Cazzola, D., and Metcalfe, B. W. (2024). Exploring

the ’EarSwitch’ concept: A novel ear based control

method for assistive technology. Journal of Neuro-

Engineering and Rehabilitation, 21(1):210.

Ismail, S., Akram, U., and Siddiqi, I. (2021). Heart rate

tracking in photoplethysmography signals affected by

motion artifacts: A review. EURASIP Journal on Ad-

vances in Signal Processing, 2021(1):5.

Lindholm, P., Blogg, S. L., and Gennser, M. (2007). Pulse

oximetry to detect hypoxemia during apnea: Compar-

ison of finger and ear probes. Aviation, Space, and

Environmental Medicine, 78(8):770–773.

Longmore, S. K., Lui, G. Y., Naik, G., Breen, P. P.,

Jalaludin, B., and Gargiulo, G. D. (2019). A Compar-

ison of Reflective Photoplethysmography for Detec-

tion of Heart Rate, Blood Oxygen Saturation, and Res-

piration Rate at Various Anatomical Locations. Sen-

sors, 19(8):1874.

Martin, D., Johns, C., Sorrell, L., Healy, E., Phull, M., Olu-

sanya, S., Peters, M., and Fabes, J. (2024). Effect of

skin tone on the accuracy of the estimation of arterial

oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry: A systematic re-

view. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 132(5):945–956.

Moc¸o, A. V., Stuijk, S., and de Haan, G. (2016). Skin

inhomogeneity as a source of error in remote PPG-

imaging. Biomedical Optics Express, 7(11):4718–

4733.

Monk, E. (2023). The Monk Skin Tone Scale.

Nitzan, M., Nitzan, I., and Arieli, Y. (2020). The Vari-

ous Oximetric Techniques Used for the Evaluation of

Blood Oxygenation. Sensors, 20(17):4844.

Nowara, E. M., McDuff, D., and Veeraraghavan, A. (2020).

A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Skin Tone and Gen-

der on Non-Contact Photoplethysmography Measure-

ments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference

on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Work-

shops, pages 284–285.

Olive, S., Twentyman, O., and Ramsay, C. (2016). Com-

parison of fingertip and earlobe pulse oximetry with

arterial blood gas results. European Respiratory Jour-

nal, 48(suppl 60).

Perry, E. T. and Shelley, W. B. (1955). The histology of the

human ear canal with special reference to the cerumi-

nous gland. The Journal of Investigative Dermatol-

ogy, 25(6):439–451.

Pirzada, P., Wilde, A., and Harris-Birtill, D. (2024). Remote

Photoplethysmography for Heart Rate and Blood

Oxygenation Measurement: A Review. IEEE Sensors

Journal, 24(15):23436–23453.

Seifi, S., Khatony, A., Moradi, G., Abdi, A., and Najafi, F.

(2018). Accuracy of pulse oximetry in detection of

oxygen saturation in patients admitted to the intensive

care unit of heart surgery: Comparison of finger, toe,

forehead and earlobe probes. BMC Nursing, 17(1):15.

Sjoding, M. W., Dickson, R. P., Iwashyna, T. J., Gay, S. E.,

and Valley, T. S. (2020). Racial Bias in Pulse Oxime-

try Measurement. New England Journal of Medicine,

383(25):2477–2478.

Stinson, M. R. and Lawton, B. W. (1989). Specification of

the geometry of the human ear canal for the prediction

of sound-pressure level distribution. The Journal of

the Acoustical Society of America, 85(6):2492–2503.

Tian, S. (2024). Shades of Skin: Limitations

of the Fitzpatrick Scale with CIELAB.

https://nhsjs.com/2024/shades-of-skin-limitations-of-

the-fitzpatrick-scale-with-cielab/.

Vogel, S., Hulsbusch, M., Starke, D., and Leonhardt, S.

(2007). In-Ear Heart Rate Monitoring Using a Micro-

Optic Reflective Sensor. In 2007 29th Annual In-

ternational Conference of the IEEE Engineering in

Medicine and Biology Society, pages 1375–1378.

Weatherall, I. L. and Coombs, B. D. (1992). Skin Color

Measurements in Terms of CIELAB Color Space Val-

ues. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 99(4):468–

473.

Western, D. G. (2012). Bioelectric Signal Analysis to Ex-

pose Nervous Control of the Human Heart. Doctoral,

University College London.

Yossef Hay, O., Cohen, M., Nitzan, I., Kasirer, Y.,

Shahroor-karni, S., Yitzhaky, Y., Engelberg, S., and

Nitzan, M. (2018). Pulse Oximetry with Two Infrared

Wavelengths without Calibration in Extracted Arterial

Blood. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 18(10):3457.

WHC 2025 - Special Session on Wearable HealthCare

1052