Position Paper: Enhancing the Learning and Mastery of Academic

Writing in the Serbian Language Through an AI Tool with Adaptive

Scaffolding

Teodor Sakal Francišković

a

, Dušan Gajić

b

, Nikola Luburić

c

and Jelena Slivka

d

Department of Computing and Control Engineering, Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad,

Trg Dositeja Obradovića 6, Novi Sad, Serbia

Keywords: Academic Writing, Artificial Intelligence in Education, AI Tools, Adaptive Scaffolding.

Abstract: Academic writing is a significant challenge for many learners striving for proficiency. Adaptive scaffolding

techniques and AI tools in education have proven effective in addressing this challenge and supporting

learners in improving their academic writing skills when used correctly. This position paper proposes

combining adaptive scaffolding techniques with AI tools in a public university's final year academic writing

course to enhance the learning experience and mastery of academic writing skills in Serbian. The proposed

plan outlines the course structure and details how the AI-driven adaptive scaffolding techniques will be

integrated to support the learning experience, focusing on summative and formative feedback from the AI

tool. The proposed plan is a work in progress. It will be implemented in the next iteration of the course for

evaluation, taking into account potential counter-arguments and their impact on the tool's development and

the student's learning experience and outcomes. This study will analyse our plan's effectiveness in enhancing

the learning experience and outcomes. The expected outcome is to assist students in their learning while

contributing to the development of AI in education and the Serbian language.

1 INTRODUCTION

Academic writing is a formal kind of writing used in

higher education, which contains the writer’s

evidence-based perspectives on a given subject of

interest (Oshima & Hogue, 2007). The academic

paper should be written so that the sentences are clear

and well-organised, with the primary goal of making

the presented arguments understandable to the target

audience. Furthermore, academic writing is expected

to be objective, precise, and consistent with the

terminology within its discipline (Paltridge, 2004).

Academic writing, a key struggle for many

learners aiming for proficiency (Mason & Atkin,

2021), has been difficult to master for many students

(Sağlamel & Kayaoğlu, 2015). Learners often fail to

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5747-6390

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0495-8788

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2436-7881

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0351-1183

1

https://grammarly.com/

2

https://www.wordtune.com/

3

https://paperpal.com/

reach the expected profficiency level, particularly

when lacking prior knowledge or the ability to adapt

it to academic requirements (Reiff & Bawarshi, 2011;

Soiferman, 2014; Tawalbeh & Al-zuoud, 2013).

Scaffolding has proven effective in addressing these

challenges by offering structured support, such as

guidance in goal-setting, skill development, and self-

reflection, to help learners adapt and progress (Lin et

al., 2012; Wood et al., 1976; Cotterall & Cohen,

2003; Walqui, 2006).

With the rise of AI in education (AI, AIEd) over

the past decade (Chiu et al., 2023), AI tools like

Grammarly

1

, WordTune

2

, and Paperpal

3

have

emerged to improve academic writing. These tools

analyse English text, suggest enhancements, and

detect errors. However, they offer general feedback,

Franciškovi

´

c, T. S., Gaji

´

c, D., Luburi

´

c, N. and Slivka, J.

Position Paper: Enhancing the Learning and Mastery of Academic Writing in the Serbian Language Through an AI Tool with Adaptive Scaffolding.

DOI: 10.5220/0013415200003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 355-362

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

355

lack personalisation, and provide limited multilingual

support. Incorporating scaffolding that adapts to

learners' prior knowledge and pace and supports

multiple languages can create a tailored approach,

enabling diverse learners to progress effectively.

Using AI tools for academic writing enhances

satisfaction and improves paper quality (Nazari et al.,

2021; Malik et al., 2023).

This position paper proposes a plan to enhance

learners' academic writing skills in the Serbian

language, focusing on strategies to maintain

continuous engagement and provide personalised

support, with scaffolding applied through a custom

AI tool to guide learners progressively and provide

tailored support at each stage of their learning.

Additionally, this plan would align with one of the

key goals of our country's Scientific and

Technological Strategy

45

, namely the development of

AIEd and science. The proposed plan will be tested in

an undergraduate academic writing course at a public

Serbian university in the last semester of a Software

Engineering study program by evaluating predefined

research questions (RQs). Some of those RQs are:

• RQ1: Does using an interactive AI academic

writing tool with adaptive scaffolding

improve student writing quality at the chapter

level compared to students who do not use

the interactive mode of the tool?

• RQ2: Do student clusters, based on their

interaction patterns with an AI academic

writing tool with adaptive scaffolding, differ

in learning outcomes in an academic writing

context?

• RQ3: How do academic writing skills evolve

over the semester among student clusters

defined by their interaction patterns with an

AI academic writing tool with adaptive

scaffolding?

• RQ4: Do evaluation results from the AI

academic writing tool align with those from

human evaluators in formative and

summative academic writing assessments?

• RQ5: How do students' perceptions of an AI

tool usage for academic writing change

before and after participating in a course that

integrates this tool?

We will evaluate our plans using quantitative and

qualitative methods. RQ1 assesses the tool’s impact

on Serbian chapter-level academic writing. RQ2 and

RQ3 identify usage patterns to guide interventions for

4

https://nitra.gov.rs/images/nauka/Strategija-nauc-tehnol-

razvoj-RS-Moc-znanja.pdf

better outcomes. RQ4 ensures alignment between

tool and human evaluations for reliable feedback.

RQ5 enhances students’ perception of AI, boosting

their learning experience and confidence. These RQs

gather explicit student feedback for iterative tool

improvement.

This position paper is organised as follows.

Chapter 2 reviews existing research on scaffolding

strategies and AI tools in academic writing. Chapter

3 examines the specific challenges students face in

academic writing, particularly in the Serbian

language context. Chapter 4 proposes our solution to

this problem. Chapter 5 states the counterarguments

to the proposed approach. Chapter 6 concludes the

position paper.

2 BACKGROUND WORK

Writing an academic paper is challenging due to

factors like structuring arguments, synthesising

credible research, and mastering grammar and

vocabulary (Malik et al., 2023). Writing anxiety, prior

knowledge, and motivational beliefs further

complicate the process (Reiff & Bawarshi, 2011;

Soiferman, 2014; Tawalbeh & Al-zuoud, 2013;

Rahimi & Zhang, 2019). Recent literature addresses

these challenges by providing scaffolding, such as

feedback and AI tools, to support learners. This

chapter will explore both approaches and review the

current state of academic writing in Serbian.

2.1 Rise of the Scaffolding Technique

in Academic Writing

The term "scaffolding" in education first appeared in

the late 20th century. Wood et al. (1976) defined it as

a process where adults assist learners with tasks

beyond their capacity, allowing them to focus on

manageable parts. This process helps complete tasks

successfully and can develop learners' competence.

Scaffolding became a popular research topic in

various fields, including academic writing.

Cotterall and Cohen (2003) proposed a

scaffolding framework for academic writing, where

learners produced two 1000-word essays, which

proved to be demanding. They suggested scaffolding

techniques to support task completion, such as linking

topics to study themes, providing a paper structure,

assisting with text and data, focusing on different

5

https://www.srbija.gov.rs/tekst/en/149169/strategy-for-

the-development-of-artificial-intelligence-in-the-

republic-of-serbia-for-the-period-2020-2025.php

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

356

essay components in each session, modeling

composition, addressing linguistic aspects, and

incorporating feedback. These techniques reduced the

learning burden and emphasised the rhetorical

context, though no quantitative evaluation was

provided.

According to Walqui (2006), scaffolding is

considered a contingent, collaborative, and

interactive process, with these characteristics being

further expanded upon in the educational context.

Building on this, the authors defined several

instructional scaffolding techniques used when

teaching academic paper writing: modelling,

bridging, contextualisation, building schema, re-

presenting text, and developing metacognition. For

the presented techniques to successfully enhance

learners’ academic writing skills, the authors stated

that it is not enough to use them but to highlight their

purpose to the learners.

Learners' prior knowledge is crucial for tailoring

scaffolding strategies to their needs. Spycher (2017)

identified learning stages in academic writing for

adaptive scaffolding, including knowledge building,

language exploration, guided and independent text

construction, and reflection. Spycher (2017) and

Piamsai (2020) studied scaffolding's effect on

students' writing performance and attitudes toward

cognitive, metacognitive, and affective scaffolding.

Writing scores improved significantly with

scaffolding, compared to pretest results. A 4-point

Likert scale showed positive student attitudes toward

all forms of scaffolding, enhancing the overall

learning experience. Wu and Alrabah (2023) found

that rhetorical and adaptive prior knowledge

scaffolding were the most impactful techniques.

2.2 Usage and Perception of AI Tools

in Academic Writing

AI tools in academic writing have grown significantly

in the past five years. In a survey by Chemaya and

Martin (2024), students, professors, and postdocs

were asked whether AI tools like ChatGPT

6

and

Grammarly should be acknowledged for fixing

grammar and rewriting text in academic papers. Most

participants agreed that grammar corrections did not

need to be acknowledged. However, opinions on text

rewriting varied based on prior language knowledge

and academic role. Both students and postdocs

emphasised the importance of acknowledging AI

tools for text modifications, highlighting the

6

https://chatgpt.com/

increasing prevalence of these tools in academic

writing.

Nazari et al. (2021) designed a course that used

AI tools to enhance academic writing skills and

knowledge. By comparing results between students

who had access to Grammarly and those who did not,

they confirmed that AI tools could improve students'

academic writing skills. The study also showed that

AI tools enhanced the learning experience, positively

impacting self-efficacy, engagement, and academic

emotion. The benefits of using Grammarly were

likely due to its ability to facilitate self-correction,

enabling users to refine their writing before

submitting it for final evaluation.

Some of the findings reported by Malik et al.

(2023) align with those of Nazari et al. (2021), further

confirming that AI tools enhance students' writing

proficiency. However, many students raised concerns

about the potential negative impact of AI tool usage

on creativity and critical thinking, as well as the rise

of misinformation and inaccuracies in research

papers. The study emphasises that AI tools should

support, rather than replace, writers' creativity. It is

important to note that this study did not consider

students' prior knowledge when surveying them on

AI tool usage in academic writing.

2.3 AI Support for Academic Writing

in Serbian Language

Although there has been limited support for

leveraging AI to enhance academic writing in the

Serbian language, some progress has been made in

developing linguistic tools. These tools mainly

provide advancements in grammar correction, spell-

checking, and morphological analysis, which could

serve as a foundational stepping stone for future

development of AI-powered solutions to support

learning academic writing in Serbian.

One such tool (anSpellChecker) was developed

by (Ostrogonac et al. 2012) to assist with corrections

in audio-to-text transcription. Each word was

searched for in an accentual-morphological lexicon.

If a match was found, the output included potential

base forms of the word and grammatical information

such as case, number, gender, and word category.

Otherwise, the word was flagged as incorrect.

BERTić (Ljubešić & Lauc, 2021), a transformer-

based architecture, was trained on extensive datasets

from Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian

text. It has been successfully applied to tasks such as

part-of-speech tagging, named entity recognition, and

Position Paper: Enhancing the Learning and Mastery of Academic Writing in the Serbian Language Through an AI Tool with Adaptive

Scaffolding

357

commonsense reasoning, achieving higher results

than state-of-the-art models. Because transformer

models offer flexibility in fine-tuning and prompting

for specific purposes, researchers and educators may

use them to enhance academic writing (Weng, 2024).

Empirical studies on using AI tools for academic

writing in Serbian are currently lacking, presenting a

critical research gap. Addressing this gap could

advance support for academic writing in low-resource

languages and contribute to developing more

accessible AI tools. However, studies highlighted the

significant limitations of AI-driven tools when

applied to low-resource languages, where tasks such

as translation and annotation often fell short of

human-level performance (Jadhav et al., 2024;

Lankford et al., 2023). The lack of specialized AI

resources for such languages remains a major barrier

to improving academic writing capabilities.

3 PROBLEM STATEMENT

The primary objective of our course is to equip

students with the necessary academic writing skills.

Mastering these skills enhances critical thinking and

the ability to articulate complex ideas (Tahıra &

Haıder, 2019). Furthermore, academic writing helps

students develop communication skills crucial for

academic and career success (Gupta et al., 2022).

Research has shown that students often struggle

to master academic writing skills (Mason & Atkin,

2021). This issue is particularly pronounced among

engineering and technical students, who face

additional challenges due to their strong focus on

technical expertise at the expense of writing skills and

their limited exposure to academic writing standards.

Consequently, many engineering and technical

students perceive writing as a secondary task, further

complicating their ability to produce clear and well-

organised academic papers (Rosales et al., 2012;

Colwell et al., 2011).

These challenges were evident in earlier

versions of our academic writing course within a

software engineering program, highlighting its

suitability for our initiative to enhance students'

writing skills through AI-based tools and adaptive

scaffolding techniques. Additionally, integrating AI

into education and science is a key objective of

Serbia’s Scientific and Technological Strategy,

making our initiative timely and aligned with national

priorities. By addressing these challenges, we aim to

improve students' academic writing abilities, support

their educational growth, and contribute to broader

strategic goals.

We plan to conduct an empirical study to

evaluate the effectiveness of enhancing students'

learning experience and academic writing skills in a

Serbian public university's final-year course by

incorporating adaptive AI-driven scaffolding

techniques. The initiative will be implemented within

the "Software Engineering and Information

Technology" undergraduate program, specifically

targeting the "Oral and Written Communication

Skills in Technical Disciplines" course, which

currently has around 80 students. Efforts are

underway to include this course in an additional study

program, increasing the total number of participants

to 200. This chapter outlines the course context, its

structure, and students' dissatisfaction with the

course.

3.1 Course Structure

The main objective of the earlier course iterations was

a writing task aiming to develop and assess students'

writing skills. The writing task involved writing a

technical paper in which students selected a topic of

interest from the software engineering field. The

structure of the paper was predefined and included:

● problem definition – defines essential

concepts for understanding the problem,

highlights its societal importance, and

outlines the expected solution behaviour and

target user groups;

● theoretical background - defines key

concepts, derives systems’ requirements,

and discusses possible solutions;

● solution – provides an in-depth explanation

of the solution;

● solution validation – explains the validation

process and measurements and the expected

outcomes, ensuring the reproducibility of

the validation procedure; presents and

discusses the results of the experiments,

highlighting the solution's strengths,

limitations, and applicable contexts.

Following Kirschner and Van Merrienboer

(2008), students were offered a structured course that

guided them through the incremental writing of their

technical papers. The writing task was broken into

smaller sections, allowing students to improve their

work without feeling overwhelmed (Wischgoll,

2017). Each section corresponded to a different

chapter, with strict deadlines for submission. At the

start of each chapter, lectures communicated

standards for both content and style, covering

technical aspects like working in Word and LaTeX.

These lectures ensured that students were familiar

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

358

with both practical elements (e.g., paper structure,

referencing) and conceptual elements (e.g., critical

thinking, argumentation) of academic writing.

Before each chapter’s deadline, students were

allowed one submission to receive formative

feedback from the teaching assistants (TAs). They

had strict deadlines for both requesting and receiving

this feedback. To encourage participation, a small

number of points – counted towards the final grade –

were awarded for obtaining feedback. However,

students could not access their feedback immediately

and had to wait for it to be provided.

Rubrics related to the general writing style and

each chapter’s content were defined to limit grading

subjectivity. Three independent evaluators (TAs)

evaluated the papers, each marking a portion.

3.2 the Main Area of Student

Dissatisfaction

After the course ended, students voluntarily

completed an anonymous questionnaire to share their

perceptions of the course. Additionally, TAs were

interviewed to gather their views on the feedback and

grading processes.

The timeliness of feedback was a significant

concern for the TAs, who expressed that the time

constraints and pressure often affected its quality.

Students expressed dissatisfaction with the three

evaluators' inconsistent revision and marking process.

Despite the use of predefined rubrics, the inherent

subjectivity of human grading posed a significant

challenge. This finding aligns with existing research,

emphasising the prevalence of grading

inconsistencies in large classes with multiple

evaluators, often resulting in inconsistent grade

assignments (Haines, 2021; Hounsell, 1995).

Inconsistent feedback on academic work can

negatively impact students’ motivation and

performance. It may also discourage them from

engaging in similar tasks in the future (Wisniewski et

al., 2020; Gnepp et al., 2020). Consistent, timely, and

personalised feedback should be given to improve the

course, as it would likely increase student motivation

and encourage greater engagement with the learning

process.

4 PROPOSED SOLUTIONS

The incorporation of AI tools in the learning process

of academic writing has not only been positively

received by students but has also led to improved

outcomes in the final evaluation of academic papers.

These tools offer immediate feedback about the

written text, which helps students refine their work

iteratively (Nazari et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2023; de

Diego et al., 2021). Additionally, the tool will provide

consistent feedback and evaluation, as it will be

trained to apply the same rubrics when delivering

summative feedback.

Applying adaptive scaffolding during the learning

process of academic writing has proven to be an

effective strategy for supporting students. This

technique considers learners’ prior knowledge and

learning trajectories, providing support that meets

each learner's needs (Spycher, 2017; Wu & Alrabah,

2023).

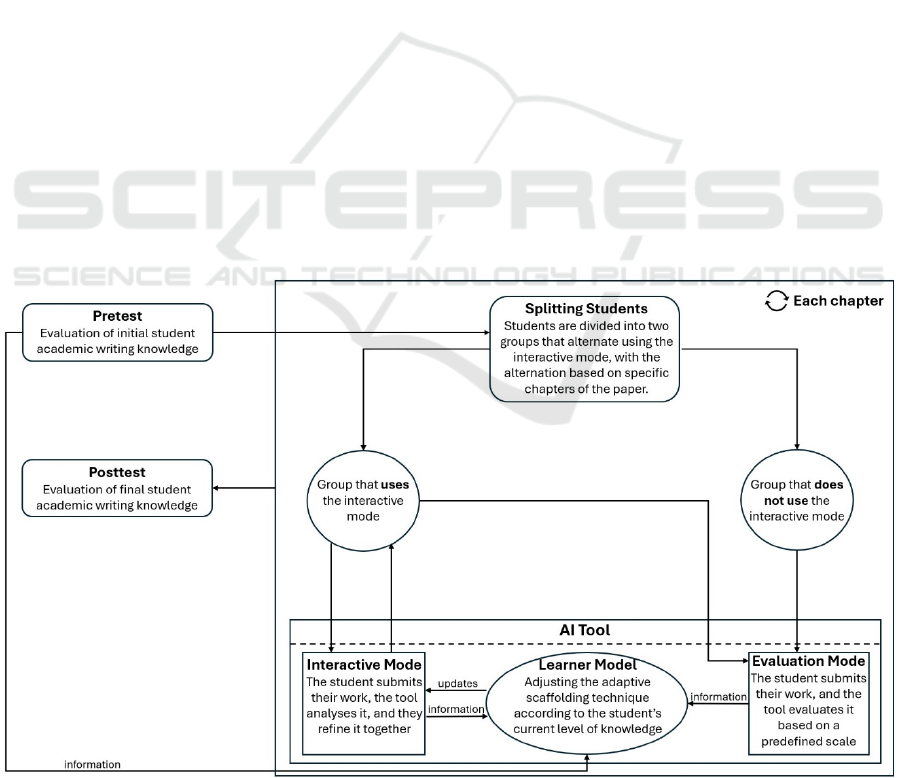

This chapter proposes a plan for integrating

adaptive scaffolding techniques into developing a

custom AI tool to enhance the students' learning

experience and academic writing. Figure 1 presents

an envisioned course structure based on this plan.

4.1 Creation and Structure of the Tool

Students can interact with the tool in two modes:

interactive and evaluation. In interactive mode,

students can submit work-in-progress papers for

analysis based on predefined criteria. The tool will

provide tailored, instant, formative feedback for

immediate use, helping students enhance their work.

Additionally, students can ask for help on specific

issues, allowing for targeted guidance. The tool also

updates the learner model by analysing interactions

and identifying difficulties, ensuring feedback is

personalised based on prior knowledge and tool

interactions. This approach has been positively

received and linked to improved evaluation outcomes

(Spycher, 2017; Wu & Alrabah, 2023).

The evaluation mode entails providing formative

and summative feedback by marking the final

versions of the papers’ chapters using predefined

rubrics. Even though human intervention will be

needed to validate tools’ output when assigning the

final grade, the idea is to make the marking process

less complex for TAs and more consistent. Doing so

reduces the risk of students feeling demotivated and

dropping their performance throughout the course

(Wisniewski et al., 2020; Gnepp et al., 2020). The

main difference between interactive and evaluation

modes lies in their purpose: interactive mode focuses

on providing formative feedback during the writing

process while enabling direct interaction with

students, whereas evaluation mode provides both

formative and summative feedback on final

submissions using predefined rubrics.

Position Paper: Enhancing the Learning and Mastery of Academic Writing in the Serbian Language Through an AI Tool with Adaptive

Scaffolding

359

The learner model, a core component of the AI

tool, is central to tracking and analysing student

progress, personalising the tool's feedback mechanism.

It collects data from both interactive and evaluation

modes to adapt the interactive experience based on

students' challenges and work patterns, providing a

more tailored approach. For instance, if students

repeatedly use similar phrasing in their writing, the

learner model will recognise this and, in future

interactions, guide students to diversify their

vocabulary and sentence structures. By offering

abstract rules and personalised feedback, the tool helps

students understand how to improve and why specific

changes enhance their writing. This deeper

understanding accelerates learning as students

internalise principles and need fewer concrete

examples over time. The learner model ensures an

effective and engaging learning experience by

continuously tracking progress. The tool creation

process will consist of two parts. Firstly, the tool will

be trained before the beginning of the course. This

phase will focus on feeding the tool with the

foundational knowledge of academic writing, such as

language grammar and paper structure. The second

phase of developing the tool will focus on adapting it

to meet the individual needs of each student throughout

the course duration. This personalisation will consider

their initial knowledge, assessed through a pretest, and

their learning pace throughout the semester, all of

which will be fed to the learner model.

4.2 New Course Learning Design

Figure 1 presents the updated course structure.

Initially, students will complete a pretest to assess

their prior knowledge of academic writing. The

pretest will include tasks designed to assess students'

ability to evaluate a given text, focusing on whether

it follows a specific structure, complies with proper

grammar, and maintains an appropriate style. These

tasks aim to measure students' initial awareness of

key academic writing principles and provide a

baseline for personalised guidance through the tool.

The course will follow an iterative flow, with

each iteration focusing on one of the four paper

chapters previously described in section 3.1. Each

iteration starts with an in-face lecture that gives the

students instructions on completing the following

section of their academic paper. Students are then

split into two groups: an experiment group that uses

the interactive mode and the control group that does

not use it. We switch these groups in each iteration,

ensuring students write two chapters using each

mode. This way, we can evaluate whether our

intervention enhances the quality of the resulting

chapters. Furthermore, this approach allows students

to form opinions about the tools’ effectiveness. After

completion, both groups’ chapters are evaluated

using the tools’ evaluation mode. In contrast to the

interaction mode, all students can use the evaluation

mode multiple times for each paper’s section.

Figure 1 - Course structure.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

360

TAs will assign final marks to paper chapters,

using the tool's evaluation output as a reference while

verifying its accuracy. The posttest will mirror the

pretest structure, enabling us to assess whether the

tool has significantly improved students’ academic

writing skills. The tool's effectiveness will be

evaluated by answering a set of research questions,

some of which were outlined in Section 1.

Additionally, students will complete a questionnaire

on their perception of using the AI tool and adaptive

scaffolding to improve their academic writing skills.

5 COUNTERARGUMENTS

While we plan to create a tool to encourage students

to engage actively in dialogue with AI, we are

mindful of the potential risks associated with its

usage. Overreliance on AI in academic writing has

been argued to diminish students' critical thinking

(Lin, 2023), potentially leading to less engagement

with lecture materials and a shallower understanding

of the content. Another concern is feedback

misinterpretation, where students might

misunderstand the suggestions provided, leading to

unintentional errors.

Ethical concerns about AI usage in academic

writing are widely discussed, with learners raising

issues related to authorship, originality, and integrity.

The rise of AI-generated content has also contributed

to misinformation in research, often due to inadequate

verification by researchers. These challenges

highlight the need for stricter guidelines and

accountability in AI-assisted academic work (Malik

et al., 2023; Chemaya & Martin, 2024).

From a technical perspective, creating an AI-

based educational tool is complex due to resource

constraints and implementation challenges. High-

quality, unbiased datasets are essential for training

while developing user-friendly software and securing

sufficient computing power can be costly. Real-time

AI feedback also requires efficient processing

capabilities. These challenges necessitate strong

financial and technical support from the university

(Eden et al., 2024).

6 CONCLUSIONS

Learning academic writing remains challenging for

many, particularly those striving for proficiency.

Support for the Serbian language in academic writing

is still limited. However, adaptive scaffolding

techniques and the integration of AIEd have generally

been well-received by learners, with positive

perceptions and favorable outcomes reported. A

custom AI tool using adaptive scaffolding will be

developed and integrated into our university’s course

with a redesigned flow to address these challenges.

By providing instant feedback through interactions

with the AI tool, students will improve their self-

efficacy and engagement in academic writing,

making it easier to master. The AI tool will also

address frustrations related to marking subjectivity.

The proposed plan has the potential to significantly

enhance the academic writing learning experience,

encouraging students to engage more with similar

tasks in the future. It also aligns with Serbia's

scientific and technological goals of integrating

AIEd, providing greater support for academic writing

in Serbian. The answers to the proposed research

questions will further refine current strategies to

improve the academic writing learning process.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research has been supported by the Ministry of

Science, Technological Development and Innovation

(Contract No. 451-03-65/2024-03/200156) and the

Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi

Sad through project “Scientific and Artistic Research

Work of Researchers in Teaching and Associate

Positions at the Faculty of Technical Sciences,

University of Novi Sad” (No. 01-3394/1).

REFERENCES

Oshima, A., & Hogue, A. (2007). Introduction to academic

writing (p. 3). Pearson/Longman.

Paltridge, B. (2004). Academic writing. Language teaching,

37(2), 87-105.

Banks, D. Approaching the journal des Sçavans, 1665–1695:

a manual analysis of thematic structure. J World

Languages. 2015; 2 (1): 1–17.

Mason, S., & Atkin, C. (2021). Capturing the struggle: adult

learners and academic writing. Journal of Further and

Higher Education, 45(8), 1048-1060.

Sağlamel, H., & Kayaoğlu, M. (2015). English major

students' perceptions of academic writing: A struggle

between writing to learn and learning to write. Tarih

Kultur Ve Sanat Arastirmalari Dergisi-Journal Of

History Culture And Art Research, 4(3).

Reiff, M. J., & Bawarshi, A. (2011). Tracing discursive

resources: How students use prior genre knowledge to

negotiate new writing contexts in first-year composition.

Written Communication, 28(3), 312-337.

Position Paper: Enhancing the Learning and Mastery of Academic Writing in the Serbian Language Through an AI Tool with Adaptive

Scaffolding

361

Soiferman, L. K. (2014). Understanding the Complexities of

Prior Knowledge. Online Submission.

Tawalbeh, A., & Al-zuoud, K. M. (2013). The effects of

students' prior knowledge of English on their writing of

researches. International Journal of Linguistics, 5(3),

156.

Lin, T. C., Hsu, Y. S., Lin, S. S., Changlai, M. L., Yang, K.

Y., & Lai, T. L. (2012). A review of empirical evidence

on scaffolding for science education. International

Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 10, 437-

455.

Chiu, T. K., Xia, Q., Zhou, X., Chai, C. S., & Cheng, M.

(2023). Systematic literature review on opportunities,

challenges, and future research recommendations of

artificial intelligence in education. Computers and

Education: Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100118.

Nazari, N., Shabbir, M. S., & Setiawan, R. (2021).

Application of Artificial Intelligence powered digital

writing assistant in higher education: randomized

controlled trial. Heliyon, 7(5).

Malik, A. R., Pratiwi, Y., Andajani, K., Numertayasa, I. W.,

Suharti, S., & Darwis, A. (2023). Exploring artificial

intelligence in academic essay: higher education

student's perspective. International Journal of

Educational Research Open, 5, 100296.

Rahimi, M., & Zhang, L. J. (2019). Writing task complexity,

students’ motivational beliefs, anxiety and their writing

production in English as a second language. Reading and

Writing, 32(3), 761-786.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of

tutoring in problem solving. Journal of child psychology

and psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.

Cotterall, S., & Cohen, R. (2003). Scaffolding for second

language writers: Producing an academic essay. ELT

journal, 57(2), 158-166.

Walqui, A. (2006). Scaffolding instruction for English

language learners: A conceptual framework.

International journal of bilingual education and

bilingualism, 9(2), 159-180.

Piamsai, C. (2020). The Effect of Scaffolding on Non-

Proficient EFL Learners' Performance in an Academic

Writing Class. LEARN Journal: Language Education

and Acquisition Research Network, 13(2), 288-305.

Spycher, P. (2017). Scaffolding Writing Through the"

Teaching and Learning Cycle". WestEd.

Wu, S. H., & Alrabah, S. (2023). Instructional Scaffolding

Strategies to Support the L2 Writing of EFL College

Students in Kuwait. English Language Teaching, 16(5),

53.

de Diego, I. M., González-Fernández, C., Fernández-Isabel,

A., Fernández, R. R., & Cabezas, J. (2021). System for

evaluating the reliability and novelty of medical

scientific papers. Journal of Informetrics, 15(4), 101188.

Chemaya, N., & Martin, D. (2024). Perceptions and detection

of AI use in manuscript preparation for academic

journals. Plos one, 19(7), e0304807.

Ljubešić, N., & Lauc, D. (2021). BERTi\'c--The Transformer

Language Model for Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin

and Serbian. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.09243.

Rosales, J., Moloney, C., Badenhorst, C., Dyer, J., & Murray,

M. (2012). Breaking the barriers of research writing:

Rethinking pedagogy for engineering graduate research.

Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education

Association (CEEA).

Colwell, J. L., Whittington, J., & Jenks, C. F. (2011, June).

Writing challenges for graduate students in engineering

and technology. In 2011 ASEE Annual Conference &

Exposition (pp. 22-1714).

Wischgoll, A. (2017, July). Improving undergraduates’ and

postgraduates’ academic writing skills with strategy

training and feedback. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 2,

p. 33). Frontiers Media SA.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of

feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational

feedback research. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 487662.

Gnepp, J., Klayman, J., Williamson, I. O., & Barlas, S.

(2020). The future of feedback: Motivating performance

improvement through future-focused feedback. PloS

one, 15(6), e0234444.

Weng, B. (2024). Navigating the Landscape of Large

Language Models: A Comprehensive Review and

Analysis of Paradigms and Fine-Tuning Strategies. arXiv

preprint arXiv:2404.09022.

Haines, C. (2021). Assessing students' written work: marking

essays and reports. Routledge.

Hounsell, D. (1995). Marking and commenting on essays. F.

Forster, D, Hounsell & S. Thompson (Eds.) Tutoring and

Demonstrating: A Handbook, 51-64.

Lin, Z. (2023). Supercharging academic writing with

generative AI: framework, techniques, and caveats.

Eden, C. A., Chisom, O. N., & Adeniyi, I. S. (2024).

Integrating AI in education: Opportunities, challenges,

and ethical considerations. Magna Scientia Advanced

Research and Reviews, 10(2), 006-013.

Jadhav, S., Shanbhag, A., Thakurdesai, A., Sinare, R., &

Joshi, R. (2024). On Limitations of LLM as Annotator

for Low Resource Languages. arXiv preprint

arXiv:2411.17637.

Lankford, S., Afli, H., & Way, A. (2023). adaptmllm: Fine-

tuning multilingual language models on low-resource

languages with integrated llm playgrounds. Information,

14(12), 638.

Tahıra, M., & Haıder, G. (2019). The Role Of Critical

Thinking In Academic Writing: An Investigation Of Efl

Students’perceptions And Writing Experiences.

International Online Journal of Primary Education, 8(1),

1-30.

Gupta, S., Jaiswal, A., Paramasivam, A., & Kotecha, J.

(2022, June). Academic writing challenges and supports:

Perspectives of international doctoral students and their

supervisors. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 7, p.

891534). Frontiers Media SA.

Kirschner, P., & Van Merrienboer, J. J. (2008). Ten steps to

complex learning: A new approach to instruction and

instructional design. In 21st century education: A

reference handbook (pp. 244-253). SAGE Publications

Ltd.

S. Ostrogonac, M. Bojanić, N. Vujnović-Sedlar, S. Suzić,

“Detektor Pravopisnih i Štamparskih Grešaka za Srpski

Jezik“– Technical report, https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/322400157_Detektor_stamparskih_i_pr

avopisnih_gresaka_za_srpski_jezik_anSpellChecker,

2012.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

362