EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

Armin Egetenmeier

a

, Zoe Jebing and Sven Strickroth

b

LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

fi

Keywords:

Oral Examination, Exam Log, e-Assessment System, Digital Support Tool, Assessment Analytics.

Abstract:

Along with written examinations, oral exams are an important form of assessment in higher education, providing

examiners with deep insight into student understanding. However, conducting oral exams often requires

significantly more effort as there is the need to carefully record all noteworthy incidents and results for legal and

formal requirements. To ease the work of examiners and observers while increasing the validity and reliability

of this type of assessment, a digital support software is proposed. This paper describes the design process

of such a digital tool to support the implementation and note taking of oral exams, taking into account legal

requirements, current oral examination practices, and the needs of both examiners and observers based on

interviews and existing literature. The results were used to derive a concept and to implement a proof-of-concept

prototype, which was positively validated in a small interview study. Features include automatic time recording

and a guided, structured but flexible data collection (i. e. clickable items and free-text fields) and currently focus

primarily on supporting observers. Further ideas regarding assessment analytics using the data are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Examinations are an essential part of education as a

summative assessment of learning outcomes (Kirk-

wood and Price, 2008). The goal of these assessments

is to evaluate the learners’ knowledge, understand-

ing, skills, or competencies of/in a subject. In higher

education, there are a variety of assessment formats,

including paper-based tests, written exams, student

assignments (e. g., portfolios, essays), or oral assess-

ments (e. g., presentations, oral exams).

Different assessment formats have individual ad-

vantages and challenges, such as scalability and the

time required for their preparation and execution. In

general, administering examinations requires a signifi-

cant amount of time and effort from educators. Early

on, institutions and examiners used existing technolo-

gies such as learning management systems (LMS),

scannable exams

1

or self-developed tools to

(semi-)

au-

tomatically grade submissions and reduce their work-

load – especially in large classes with several hun-

dred students (Strickroth and Bry, 2022). Nowadays

many generic commercial products such as LPLUS,

EvaExam, or RISR are available to manage and de-

liver assessments in all phases from their creation to

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3944-3277

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9647-300X

1

e. g., https://www.auto-multiple-choice.net/

grading, and archiving.

2

Usually, e-assessment sys-

tems only support written exams and are therefore

less useful for assessments formats such as oral ex-

ams (Memon et al., 2010). Oral exams (also known as

oral examination/assessment, or viva voce, cf. Pearce

and Lee, 2009) can be defined as an assessment in

which the response is expressed verbally rather than

in written form (Joughin, 1998). The main benefit

of oral exams is to assess students’ deep and concep-

tual understanding of knowledge (Gharibyan, 2005;

Dicks et al., 2012; Huxham et al., 2012). Here, the

examiner (typically an educator or teacher) conducts

the oral exam, asking questions and evaluating the

student’s responses, while an observer (referred to as

“Beisitzer” in German) documents the process, and

ensures that all relevant events and interactions are

recorded. Note-taking is mandatory for legal reasons

and must be recorded in a log of the exam (in Ger-

man “Pr

¨

ufungsprotokoll”). This log can be compared

to meeting minutes and contains formal information

(e. g., date, start and end times, involved persons, re-

sults), but also relevant events during the exam (e. g.,

interruptions). In the context of oral exams, technolog-

ical approaches to support teaching staff are rare.

Oral examinations have a different character com-

pared to written exams: Although both are summative

2

https://lplus.de/en/; https://evasys.de/en/; https://risr.

global/, last accessed: 2024-12-11

582

Egetenmeier, A., Jebing, Z. and Strickroth, S.

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams.

DOI: 10.5220/0013420200003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 582-593

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

formats that assess student knowledge, written exams

are static and usually use the same set of questions for

each participant. Hence, written exams can be used to

assess large number of students simultaneously, and au-

tomated grading tools (e. g., for multiple-choice ques-

tions) can be used to ensure efficiency and objectivity.

In contrast, oral exams provide a more interactive and

dynamic assessment for individual (or small groups

of) students, allowing the examiner to spontaneously

choose questions and also the student to ask questions

(e. g., in case of misunderstandings). This approach

also assesses soft skills such as communication, con-

fidence, and presentation. Even with rubrics in place,

the scoring can involve subjective judgment. Thus,

an oral exam requires a significant amount of exam-

iner time per candidate due to the sequential nature

of the exam sessions. By emphasizing reasoning and

engaging in real-time discussions for example through

follow-up questions for clarification, examiners can

gain deeper insight into students’ comprehension that

go beyond the mere recall of content. This makes

structured assessment and objective grading more dif-

ficult than in written exams. In addition, due to the

rather unstructured oral examination logs, assessment

analytics approaches are not used.

With the recent advent of (generative) AI, oral ex-

ams are “rediscovered” and used more frequently as

an alternative to asynchronous written formats to pre-

vent student misconduct (Nallaya et al., 2024). This

underscores that there is an actual need for a support

tool for this type of exam, especially for the mandatory

writing of a log.

The goal of this paper is to explore the require-

ments for a support system for oral examinations

and to propose a concept and a prototype. This re-

search was primarily conducted in the context of

science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

(STEM)/Computer Science in German universities.

This paper answers the following research questions:

•

RQ1. What are typical activities and roles of ex-

aminers and observers during an oral exam?

•

RQ2. What are the formal and functional require-

ments for a system to support examiners and ob-

servers in oral exams and what might a concept

look like?

•

RQ3. How is the developed prototype perceived

by examiners and observers?

The key contributions of the paper are a concept

for a support tool with a focus on observers for oral ex-

ams based on interviews and legal requirements from

literature, and a proof-of-concept prototype.

2 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

RESEARCH

This section presents the theoretical background and

related research on phases of examinations, the oral

assessment format, and existing support systems.

2.1 Phases of Examinations

Overall, examinations encompass three phases (cf. Mu

and Marquis, 2023): pre-exam preparation, execution,

and post-exam/review.

Besides purely administrative parts (e. g., manag-

ing student registrations, assigning students to rooms

and appointments), the preparation phase for teaching

staff includes developing assignments/tasks/questions

and putting them together for a specific exam. Frame-

works such as Bloom’s taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002)

can be used to categorize learning objectives, align

the content of the exam with them, and estimate the

difficulty of the exam. The execution of an exam may

involve the teaching staff to be present (e. g., as in-

vigilator or examiner). This phase also includes the

grading of the exam. Typically, rubrics are used for

an efficient and objective evaluation. In the review

phase, the examiner reviews and evaluates the overall

assessment, i. e. to analyzes the quality of the ques-

tions for example by calculating their actual difficulty

or item discrimination. This phase is often skipped for

paper-based and oral exams.

2.2 Oral Exams

The main characteristic of an oral exam is the verbally

expressed answer, which makes this assessment type

complex (Memon et al., 2010). This assessment format

has the potential to generate many unique learning ben-

efits, including authentic assessments (Nallaya et al.,

2024), positive effects on underrepresented groups

(Reckinger and Reckinger, 2022) and increased mo-

tivation in the subject (Delson et al., 2022). Oral

assessments are widely used in various disciplines,

such as business courses (Markulis and Strang, 2008),

medical professions (Memon et al., 2010) and social

sciences (Hazen, 2020), both nationally and interna-

tionally (Akimov and Malin, 2020).

In their review, Mu and Marquis (2023) discuss

and analyze the effectiveness of oral exams in terms of

their historical development. This includes the identi-

fication of key advantages such as fostering communi-

cation skills and deeper understanding (cf. Dicks et al.,

2012; Huxham et al., 2012) due to their interactive and

adaptive nature. Typical challenges relate to their va-

lidity, reliability and fairness, which are also discussed

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

583

in other publications (e. g., Joughin, 1998; Kang et al.,

2019; Memon et al., 2010). However, none of the re-

viewed literature has systematically investigated these

aspects of oral exams. Nonetheless, several conditions

and ideas are proposed to address these aspects such

as a specific training for examiners, using standardized

questions for each student, and evaluating with rubrics

that provide explicit criteria, or post-exam analysis

with statistical methods (cf. Memon et al., 2010; Mu

and Marquis, 2023). However, the authors omitted

details on how this can be effectively implemented for

oral exams. Especially the absence of standardized

evaluation methods and long-term quality assurance

creates vulnerability to unfair discrimination (Heppner

et al., 2022).

A practical approach taking on the known issues

are structured oral exams as used in medical and nurs-

ing education (cf. Abuzied and Nabag, 2023). Struc-

tured oral exams represent a balanced compromise

between reliability, validity, and the required effort.

These approaches typically use sophisticated templates

to simplify the tasks of examiners and observers, pro-

viding a basic structure that has been proven to result in

highly objective and valid examinations (Westhoff and

Hagemeister, 2014). Ohmann (2019) provides a rubric

for on-the-fly grading. However, these structured ap-

proaches limit the examiner’s freedom to explore the

students’ understanding beyond the pre-defined topics

(cf. Ohmann, 2019).

A focus of current research seems to be on stu-

dents’ perception (e. g., stress levels or anxiety, cf.

Baghdadchi et al., 2022) rather than roles and tasks

of examiners and observers. Guidelines are typically

proposed to support teaching staff on conducting oral

exams (Mu and Marquis, 2023; Burke-Smalley, 2014).

To train students to cope with the stress of oral ex-

ams, there is research using AI to simulate oral exams

to familiarize students with the situation, reduce stress,

and provide feedback.

3

This is, however, out of scope

for this research.

2.3 Support and e-Assessment Systems

Many support systems are available that support spe-

cific or multiple phases of the examination process.

Campus and learning management systems are often

used for exam registration and reporting of grades.

As mentioned in the introduction, there is a

plethora of (commercial) systems for conducting writ-

ten exams. These usually support all phases. Also,

LMS such as Moodle are often used to set up exams

using quiz plug-ins, conduct, and finally review them

3

https://www.uni-bayreuth.de/en/press-release/exam-

simulator, 2025-02-11

(e. g., Strickroth and Kiy, 2020). Typically, systems

used in summative assessments automatically log all

student activity to protect against appeals and can au-

tomatically assess specific item types such as multiple-

choice items. Additionally, specialized e-assessment

systems for exams have been developed in a research

context to facilitate an efficient process in specific do-

mains such as programming education with full or

semi-automatic grading (cf. Strickroth and Striewe,

2022; Strickroth and Holzinger, 2022). However, these

systems do not provide specific support for oral exams.

Many systems allow the quality of an exam and its

assessment items to be analyzed in terms of difficulty

and item discrimination. This allows to identify sub-

optimal questions in the review phase. The analysis

of data that is generated during an assessment/exam

is often referred to as Assessment Analytics (cf. Ellis,

2013) and can be seen as a subfield of learning analyt-

ics (cf. Siemens et al., 2013). Assessment Analytics

may also include an analysis of the time spent on spe-

cific questions or number of skips to identify patterns,

predictive modeling to anticipate student performance,

or data visualization to present assessment results in a

more accessible and understandable way. As a result,

the analysis can provide insight into the learning pro-

cess and inform future instructional strategies. While

these approaches can provide deeper insights, they are

typically not applicable to oral examinations, because

the data (i. e., the logs) are not available in a structured,

digital, machine-readable format.

To support oral exams, Ally (2024) proposed a tool

for scheduling oral exams and automatically assign-

ing a random examiner to a student. In addition, their

software randomly assembles questions (and model so-

lutions) from a database and provides a digital rubric

with score boxes for dimensions such as communi-

cation skills, understanding, confidence, fluency, and

accuracy. There are no freedoms for the examiner and

no deeper dialog in the exam. Also noteworthy is an

approach of Bayley et al. (2024), who used a quiz

module of an LMS to conduct a synchronous “oral”

examination with about 600 students. In their scenario,

there was a fixed time slot in which students could

answer a set of prepared, static questions by record-

ing and uploading a video using the LMS. Limitations

are, however, that there is no dialog in the exam, all

recorded videos have to be viewed and graded manu-

ally, and there is no cheating prevention.

Apart from assessment systems, there have been

recent advances in automatic speech-to-text transcrip-

tion such as OpenAI Whisper. These approaches

can significantly reduce the effort required to create

the log, however, there are still significant challenges

such as missing context and meaning, consideration

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

584

of non-verbal communication, and quality or accuracy

(Wollin-Giering et al., 2024; Kuhn et al., 2023). As

a result, careful review and manual editing is often

required to ensure a high level of quality. In addition,

an audio/video recording may not be possible for legal

or ethical reasons.

In summary, there is a research gap for a support

system for oral examinations that assists examiners

and observers. In particular, a structured recording of

student performance can assist (novice) observers in

creating good logs and may open up new possibilities

for assessment analytics in oral exams.

3 METHODOLOGY

To answer the RQs and to inform the concept of a sup-

port tool, a requirement analysis using interviews and

a literature review on examination law as well as exam

regulations (in Germany) was conducted. The inter-

views were semi-structured and held during January,

22nd and March, 15th 2024. Overall, 17 persons par-

ticipated (observers and examiners) in the interviews

from seven different universities in Germany. The in-

terview partners included ten professors (8 male, 2

female) with a lot of experience in conducting oral ex-

ams (4 to 20 years) and seven teaching assistants/PhD

students with up to three years of experience. Ten

of the interviews were conducted online and seven in

person. Please note that all examiners have been in the

role of observers themselves during their academic ca-

reers. Thus, they also took the observer’s perspective

in the interviews. Most of the interviewees (

N = 11

)

have a background in Computer Science and other

STEM fields, but also academic staff from educational

sciences and language studies participated.

The interviews included questions about the typi-

cal process of an oral examination and general aspects

such as the structure. A special focus was put on the

preparation, execution, and review phases of this type

of exam. Furthermore, the participants were asked

to bring their templates and/or authentic, anonymized

sample logs of oral examinations. The interviews were

analyzed qualitatively using Mayring’s thematic anal-

ysis method (Mayring, 2014).

Since no comparable support software exists, a

Figma

4

design prototype was prepared based on first

ideas and experiences from the authors (cf. Figure 1).

This prototype was shown at the end of the interview

to obtain feedback and suggestions for improvements.

The reason for this was to allow participants who had

no idea what a prototype might look like to give feed-

4

https://www.figma.com, last accessed: 2024-12-01

Figure 1: Example from the Figma user interface design

prototype for the oral examination log support screen.

back, but at the same time not to influence participants

by showing them a prototype too early. The design

prototype included all relevant steps an examiner or

observer would take (e. g., adding exams, questions)

before, during and after an exam. Figure 1 shows the

observer interface of the design prototype. On the left

hand side, there is a navigation bar for quick access.

The main parts (from left to right) are the selection of

a question based on a topic and the options to record

a new question and/or the student’s answers. The an-

swers can be recorded either by clicking on buttons

for pre-defined answers or by writing them into a text

field. There are additional buttons to select pre-defined

notes, to count the number of hints/tips given, and to

rate the answer using simple plus and minus buttons. A

timer indicating the duration of the exam is displayed

at the bottom, and the exam can be ended by clicking

the “End” button.

4 REQUIREMENT ANALYSIS

This sections presents the results of the interviews and

the literature review on legal regulations/requirements.

4.1 Interviews

Understanding the current practices of examiners and

observers is necessary to identify their requirements.

In addition, the interviewees were given the opportu-

nity to comment on an initial design to come up with

additional ideas to accelerate the prototyping process.

4.1.1

Generals Aspects of Oral Examinations and

Their Recording

The first aspect discussed in the interviews was the

general structure of an oral examination – the situation

where the student is assessed by the examiner and an

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

585

observer is also present. This section provides some

general information about oral exams, introduces the

roles, and explains how the exam is generally recorded.

Overall, the interviews revealed that the structure

of an oral examination in practice follows general rules,

although the characteristics are more “free and dy-

namic” as described by the interviewees. Each exam-

iner has their own examination style in terms of how

they handle and react to incorrect answers, the order

and way in which questions are asked, and also grad-

ing. Typically, examiners use a catalog of questions or

have a list of important, recurring questions (either on

paper or at least in mind), and expect certain keywords

in the answer. However, the overall understanding

of the content/concepts taught and their internal rela-

tionships/structure are often more important than the

use of technical language. Thus, even without the use

of formal language and terms, most examiners will

accept the answers as correct. Although the oral as-

sessment is a summative examination, some examiners

enjoy having a professional discussion/dialogue with

students.

The main task of the observer (typically a teaching

assistant of the examiner) is to take notes on the course

of the exam for log purposes. The way in which the log

is written also varies among assistants, depending on

their condition, experience, and individual approach

to the examination process. The log is often written

on a sheet of paper or a laptop is used with a standard

office program and then printed afterwards. While

some observers record each question and answer in

detail to allow for detailed grading, others barely take

any notes, only write down the questions and mark

the quality of an answer with plus and minus symbols,

note whether hints were given, or start writing only

when the answer is too different from the expected

solution. Shortcuts and abbreviations are often used to

efficiently keep up with the oral exam. Furthermore,

all relevant events are noted such as interruptions. At a

minimum, the date, the student’s metadata, the names

of the people involved, the start and end times, and the

final grade are noted. Finally, the log is signed by the

examiner and the observer. Information about what the

log should look like is often passed from the examiner

in charge to their observer. Typically, the examiners

received this information in the same way when they

were in the role of the observer.

Many interviewees report using templates to guide

and structure the collection of basic information for

the oral examination log. These templates are rarely

provided by the university/institution. As a result, most

interviewees have created an individual template on

their own. Three examiners brought a sample log of

an oral exam. Overall, these logs are very different in

details, content, and format. Details are discussed in

Section 4.3.

4.1.2 Descriptions of the Examination Phases

This section provides more detailed descriptions of the

process from preparation to execution to review.

The interviews show that the preparation for oral

examinations is different for both examiners and ob-

servers. In general, there is the generic and specific

preparation. Generic preparation refers to the gath-

ering of materials and possible questions as well as

taking notes on key topics of a lecture in advance of

any oral examination. This is often done only once

per module before the first examination and is reused

for reincarnations of the same module. Prior to a spe-

cific oral examination or a group of examinations on a

particular day, the examiners may do minimal prepa-

ration, often relying on their existing notes and their

experience from previous examinations. Over time,

most educators come to rely more on their gained

experience and/or notes. There are examiners who

reported that they have created question sets with ques-

tions classified by topic and Bloom’s taxonomy. There

is usually no (special) preparation for the observers.

Typically, they are already familiar with both the ex-

aminer and the subject, so additional instructions are

unnecessary. More experienced observers may already

know the questions and exam structure from previous

examinations. Not all examiners, however, provide

new observers with specific guidelines or the expected

structure of the exam. Overall, there may also be other

people or systems involved, where the students can

register for an exam.

In the following the results of the interviews re-

garding the execution of an oral examination is de-

scribed. Most often, the oral exams are conducted

as semi-structured assessments, which use a mixture

of questions from a catalog and follow-up questions

based on given answers. An archetypal structure of

this exam variation might have the following proce-

dure: The examination usually starts with a health

check question to ensure the participant is fit for the

oral exam, checking the identity, and preparing the log

by writing down the meta data resp. administrative

and academic data (i. e., name, date, subject). Then,

the examiner starts with the oral assessment. Exam-

iners often start with an easier or broader question,

which leads to follow-up questions on the same topic,

clarification of details, asking for examples or moving

on to the next topic. There are also examiners who

allow students to start with a short report on a topic

of their choice. It is also possible for the candidate

to draw sketches or to write something on paper or

a black/white board. Meanwhile the observer takes

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

586

notes on every part of the exam. These steps are re-

peated until the scheduled time for the exam is up, or

the examiner is confident of a grade and ends the exam

early. Then, the examiner asks the candidate to leave

the room so that the student’s performance can be dis-

cussed and a grade assigned. For this part, the log is

often used to revisit the course of the exam. There may

also be updates and the addition of missing parts of

questions or answers. After a grade is assigned, the

student is invited back into the room. The examiner

recalls the performance and also announces the grade.

Finally, the log is signed and sent to the examination

office – candidate’s sketches are not always included.

There are also variants such as fully structured (using

only prepared questions in a certain order) or fully

open (using no prepared or recurring questions) exams.

Exams may also contain short presentations (like in

thesis defenses or in a seminar).

Regarding a review of the oral examinations, the

interviews show that, similar to the preparation, there

are two different types of reviews. On the one hand,

some interviewees reported that they have short daily

or weekly debriefings to refine upcoming examinations.

However, this review sometimes is omitted due to the

limited time resources. On the other hand, intervie-

wees reported that at the end of a semester after a full

examination period, examiners rarely review past oral

examinations. In general, the observer is not involved

in the review after an examination phase.

Finally, ideas and requirements for a support tool

were discussed using the created Figma user interface

prototype.

4.1.3 Feedback on the Figma Prototype

Most of the interviewees had no specific idea of what

a support tool for oral exams could look like at the

beginning. Although, the majority of participants liked

the idea for a support tool and could imagine to use

such a tool. However, it was not seen as optimal for

the open, unstructured variants of oral examinations.

There was also one participant who initially thought

that such a tool is not possible at all.

The feedback shows that some changes were re-

quested to the intended structure of the user interface.

Overall, the interviewees preferred a hierarchical struc-

ture, where all lectures are presented first and after

selecting one, all specific activities/options are avail-

able. In this way, the software is assumed to be more

efficient than with the initial design idea. In addition,

the user can directly start taking notes without having

to fill in the lecture information. Other comments re-

late to the layout, which was found to be inefficient.

The buttons for selecting topics and questions (cf. Fig-

ure 1) take up a lot of spacey and yet the space for

button labels (especially for questions) may be too

small to display the content properly. Adding new

questions during an exam should be easier and the

text field should not be hidden “behind” a plus button.

The buttons for assigning pre-defined notes should be

organized into categories such as keywords, process,

or ratings for a better overview. This also includes the

tips or hints counter, which needs to be more precise

to add value to the examiner. Furthermore, help pro-

vided by the examiner can take various forms such as

explaining a specific keyword, rephrasing a question,

or moving a question back. Finally, there were com-

ments on minor adjustments such the use of clear and

familiar descriptions, terms, and icons to increase the

readability and usability of the software.

In addition, the interviewees provided new ideas

and suggested features such as an integration with

other systems (providing an interface to the exam of-

fice or to existing platforms such as the used LMS),

customization options (to meet individual needs of the

stakeholders or to provide special options for other

oral assessment types such as thesis defenses), import/

export functions (to import questions, literature, slides,

and other materials, or to analyze results outside of

the tool), assistance and recommendation features (to

order questions e. g. by usage frequency or to eval-

uate based on historic exams), and adding notes or

comments (e. g. to record details/impression about the

answers like fluency and presentation skills). Among

other suggestions, options were proposed to compare

individual exam logs either with a model solution,

historic logs or among different students (with simi-

lar questions/answers/grades). Some participants sug-

gested to upgrade the prototype to a fully-fledged ex-

amination system by integrating features to organize

the examination appointments and archive the logs af-

terwards. This would enable to completely organize

the examination within one tool.

4.2 Legal Regulations/Requirements

The following legal regulations/requirements are sub-

ject to Germany. German examination law requires to

keep a record of the execution of an oral assessment in

written format due to its highly dynamic nature (Hart-

mer and Detmer, 2022). Therefore, an observer, who

is present in addition to an examiner, takes notes to

document the progress of the oral examination in a log

of the exam. The observer should also be an expert

in the field (“sachkundiger Beisitzer” in German, cf.

Fischer, 2022), is explicitly not a second examiner and

may give advice to the examiner, but may not influence

the final result of the exam (Fischer, 2022). At least,

the observer and the student must be in the same room

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

587

to prevent cheating – fully decentralized remote oral

examinations are not allowed.

The log requirement ensures transparency and ac-

countability of the entire assessment process by provid-

ing a record of what happened during the examination.

By documenting all noteworthy events, universities

can address any potential disputes about assessment

results. Typically, a log should include information

about the people involved, the exam tasks/questions,

the exam’s duration, all noteworthy incidents such as

unintended breaks (e. g., noise pollution), and major

events of the examination with their outcomes to re-

capitulate the oral exam (Fischer, 2022). In addition,

information about the health condition of the exami-

nee before the start of the exam needs to be recorded

as well as deterioration in their condition. Unlike a

court record, a verbatim (or complete) transcript is not

necessary. Thus, without a template, the observer has

a certain degree of freedom as to the content or details

of the log and how it is written. Finally, the log must

be physically signed by the examiner and the observer

to certify its accuracy.

Some jurisdictions may require or allow audio

and/or video recording of an exam, but this is not

allowed in Germany (Fischer, 2022): On the one hand,

recordings may miss deeper levels of the examination

process, and student consent is required for privacy rea-

sons (cf. General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR).

On the other hand, there is a risk of adapting the oral

exam to the recording system, which could negatively

affect the atmosphere of the exam, increase the stress

for the student, or reduce the validity of an oral exam.

Therefore, a manual logging is necessary.

4.3 Typical Log Template

Three examiners brought a sample log of an oral exam

and four templates were provided. Overall, these logs

and templates are very different in details, content,

and format. Therefore, these were used to compile a

generic, common version (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2: Derived generic log template.

Each log and template contains essential informa-

tion about the admission and academic data (e. g., sub-

ject, date, start and end times, and names of student,

examiner and observer) at the top. This is supple-

mented by additional data such as the student’s matric-

ulation number and major, and the answer to the health

question. The body of the log contains the questions

and optional answers in vertical form. Finally, at the

bottom of the common template, there is space for

the grade and signature lines for the examiner and the

observer. A support tool should be able to mimic this

template.

5 CONCEPT

Based on the results from the previous section, a con-

cept for a support tool for oral examination was de-

rived. This concept follows the archetypic structure

of a semi-structured oral exam for individual students

to support examiners and observers. The tool should

support in all three phases of exams. Therefore, for the

preparation phase, it needs to support entering ques-

tions into a database and possibly classifying those

into topics of a module and Bloom’s taxonomy. Ad-

ditionally, possible keywords may be entered that are

expected in students’ answers. Import options to in-

clude other material such as lecture slides or literature

can assist the examiner prepare.

The main focus of this concept is to facilitate the

most laborious task during the execution phase of the

exam, which is the creation of the log by the observer.

To guide this process, the tool concept provides a struc-

tured approach. Prior to the exam’s start, an identity

check of the student and a health check question are re-

quired. As a basic feature, a template with the relevant

admission and academic data (e. g., module, names of

the student, the examiner and the observer) is provided

as a form that ensures all information are entered for a

formally correct and accurate log. If any information

is missing, the tool will prompt the observer to enter

the relevant data to finish the preparation of the log. In

addition, a mandatory check-box for the health check

serves as a reminder to ensure the student is fit for

the exam and the answer to this question is recorded.

While the observer has to enter this data manually, the

recoding of the time (date, start and end times) can be

recorded automatically.

The exam starts with an initial question or task

from the examiner. The observer’s main task is now

to write down the questions and possibly the corre-

sponding answers, as well as notable events and details.

The concept provides flexible options for entering the

questions, either as free text or by selecting questions

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

588

stored in a database. A combination of the two should

also be possible to add details or small variations to

existing questions. Newly entered questions should

optionally be stored in the database annotated with

a topic for future reuse. The observer can enter the

student’s answers simply as a free text or by clicking

on pre-defined keywords mentioned by the student

that correspond to the question and are also stored in a

database. A combination of the two should also be pos-

sible to elaborate or comment on the student’s answers.

The time taken by the student to answer a question

is automatically recorded when the observer clicks a

button to proceed to the next question. Other recur-

ring details about students’ answers or notes about

the process are typically recorded using abbreviations

or symbols. For this part, various buttons can be set

up for quick access such as specific recurring process

notes such as postponing or skipping a question. In ad-

dition, assistance or details provided by the examiner

during the exam such as hints can also be recorded by

clicking buttons. This flexible approach using buttons

also allows quick recording of further details, which

are relevant to individual examiners for grading. For

example, various options for evaluating the answer

from simple correct/incorrect to points or plus/minus

scales. This process of asking questions and answering

is repeated until the examiner ends the examination.

During the exam a support tool should always display

the total time elapsed. At the end of the exam, a clear

log should be provided to support the evaluation. The

log can be used to recap the exam, to discuss unclear

responses, and to grade the student’s performance. To

finish the exam, a grade must be entered. In addition,

it should be possible to add general notes about the

exam to comment on details, or to add student (writ-

ten) notes or sketches to complete the log. All this

information should be stored in a database. Finally,

the log needs to be printed, signed, and sent to the

examination office. If an API exists, the grade may

also be submitted electronically.

For the review phase, the tool should provide anal-

ysis features on the data stored on the oral exams and

questions. For example, the average grade or distri-

bution of grades (within an examination phase), com-

parison of different oral exams (including historical

ones), descriptive statistics, and statistical measures

of validity or reliability. Filtering options to summa-

rize the results for a specific time frame e. g. daily or

weekly can provide feedback to the examiner. Since

all question-answer items are recorded individually,

each item can be reviewed in detail, for example to

compare among different participants the average time

needed to answer, number of questions, skips, and also

the grading. An overview of the assessment results

of different students with similar content can help the

examiner to decide how to grade. Furthermore, it is

possible to calculate the difficulty and discriminative

power of questions which allows for long-term quality

optimization (of the exams and also the lectures).

There are many possible extensions to the concept

such as a separate view for the examiner where they

have access to all notes and stored questions (incl.

statistics such as difficulty, usage frequencies, or last

usage) independent to the observer during the exam.

Also if an API exists, student registrations may be

imported and/or academic data may be automatically

read from student ID cards and inserted into the form.

Overall, the concept of the support tool provides

benefits to all three phases of oral exams, the prepara-

tion, execution, and post exam review. The log’s struc-

tured data which is available in a machine-readable

format, allows for a variety of ways to present and ana-

lyze the information. In addition, a tool should have a

modular and configurable structure to meet the needs

of different types of oral exams and the individual

preferences of examiners and observers.

5.1 Implementation of a Prototype

Based on the interviews and the derived concept, an

exploratory prototype was implemented as a proof-of-

concept (Jebing et al., 2024). As there are so many

possible features, the main focus of the implemented

prototype is to support the creation of the log by the

observer, yet the prototype was designed to cover many

of the mentioned features in one tool.

The prototype has been implemented as a client-

server architecture using web technologies (Angular

for the front-end, Node.js for the back-end using a

REST API, and MongoDB as the database), but at

this stage the prototype is intended to run on the ob-

server’s computer (e. g., on an USB key) – there is no

permissions and user/role management included, yet.

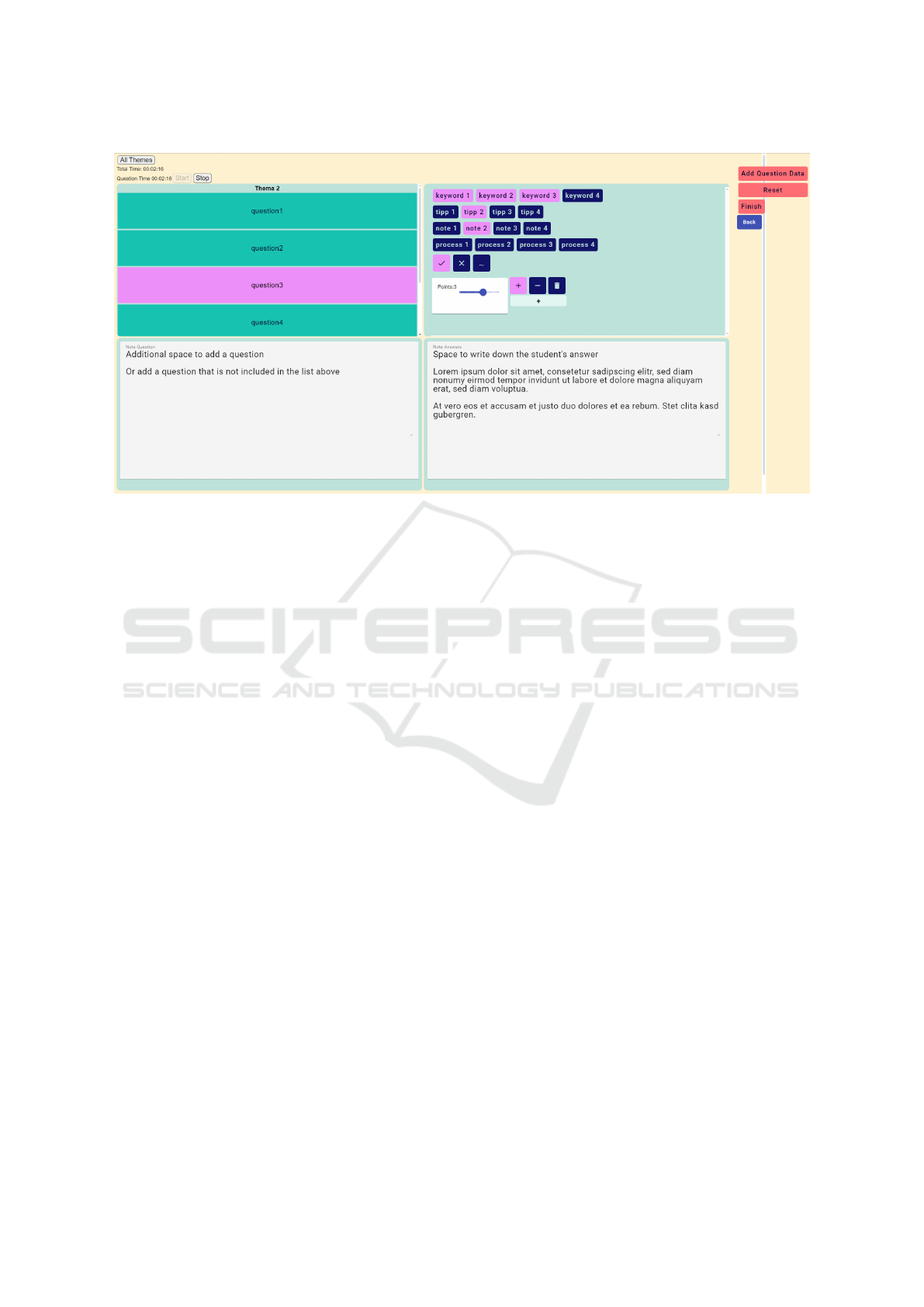

The prototype (cf. Figure 3) uses the space more

efficient (compare to Figure 1) and implements the

following key features: Exams are organized in a hi-

erarchy under the corresponding modules. When an

examination is started, academic and administrative

data are collected as described in the concept, also the

health check and recording of the start time is imple-

mented this way. The recording of questions is mainly

implemented as a large free-text field, but there are

also buttons for quick access to typical questions (also

organized in a hierarchy below their topics; left hand

side of Figure 3). These question can be added to the

database in advance or during an exam. The text field

also allows for easy additions and small changes to

the selected question. The duration of each answer

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

589

Figure 3: User interface of the input mask of the prototype filled in during an oral examination with sample entries.

is recorded automatically when a question is selected

or a question is entered into the text field. A timer

at the top left displays the elapsed time and can be

paused. The students’ answer can be recorded using

the controls on the right hand side by either selecting

relevant keywords (currently only placeholders) or by

typing notes into a free-text field – also a combination

of the two is possible. In addition, various buttons

are prepared to capture details on the process such

as counting the number of provided hints, skipping

a question and rating the answer (correct/incorrect/

sill acceptable, point scale and plus/minus symbols).

Figure 3 shows all currently hardcoded buttons that

can be displayed/hidden individually. After a student

answered a question or a question is skipped, the “Add

Question Data” must be clicked to proceed to the next

question. Finally, the “Finish” button is clicked, which

generates a “traditional” log in HTML. This can then

be used to revisit the exam and can be exported as a

PDF or printed using the browser without the need to

render HTML to a PDF itself. All (meta) data is stored

in the database.

6 EVALUATION OF THE

PROTOTYPE

The prototype was evaluated in two settings. First,

using short, unstructured interviews with three of the

former interview partners in June, 2024. After a brief

introduction, the prototype was presented and partic-

ipants’ questions and comments were addressed and

recorded. Two of the interviews were conducted in per-

son, allowing for on-site testing of the prototype. The

main goal was to get feedback on functionality, design

and usability aspects. The main results show that the

functionality of the tool fulfills the expectations of the

interviewees. The design and layout was found ade-

quate for the task, although some features were (again)

mentioned to improve the current version of the proto-

type such as import features for questions and lecture

materials, features to collect and summarize free-text

questions, and options to add details to questions such

as comments from the examiner or a classification

based on Bloom’s taxonomy. To increase “quality of

life” elements, one participant requested more options

to customize the interface (e. g., to toggle features).

Overall, there was a high interest in an updated and

extended version of the tool and actually being able to

use it, even though it is still work in progress and has

some minor bugs.

Second, the prototype was presented as a demo at

the educational technology conference DELFI in Ger-

many to discuss the idea (Jebing et al., 2024). Several

researchers, professors, and academic staff provided

feedback on the current version. A major result from

the conversations is the need for a configurable tool

that can be tailored to the own examination style and/or

variations of oral examinations. Possible customiza-

tions may be based on the subject (e. g., language stud-

ies may need different features) as well as the neces-

sary support (e. g., novice examiner or observers get a

different view than experienced teams, some features

are only enabled for specific oral assessments types

such as thesis defenses).

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

590

7 DISCUSSION

The ways how oral exams are conducted are very di-

verse (RQ1). This is in line with related research (cf.

Gharibyan, 2005; Ohmann, 2019) and the archetypic

structure distilled from the interviews has also been

reported in a similar way in other research (Willert,

2018). There also is a great variation in the way the

logs are created. However, the interviews show that

legally required parts of exams (e. g., the health check

question) are not always conducted.

The preparation of the Figma prototype turned out

to be very beneficial as most of the interviewees had

no specific idea of what a support tool for oral ex-

ams could look like. Hence, these interviewees could

directly comment on the provided example and pro-

vide helpful insights and ideas. Many innovative ideas

for a support tool were mentioned in the interviews.

While some of the interviewees showed interest in

getting recommendations for questions or suggestions

for grades, it was always emphasized that the human

examiner must always have full control and the final

decision. This again underlines the freedom which

was also mentioned by Ohmann (2019).

The main idea of the support tool concept is to

support the examiners and observers to reduce their

workload and to provide them with analysis features

and feedback (RQ2). In literature, there were differ-

ent approaches proposed to make the examiner inter-

changeable, e. g. by enforcing a fully structured oral

exam, dictating specific questions and a strict grading

rubric. Although this may help to overcome the issues

of validity and reliability, these approaches are likely to

limit the freedom of the examiner and the advantages

of oral exams to dig deeper into student understanding

(cf. Ohmann, 2019). Therefore, different support mea-

sures are required compared to existing approaches.

Still, related literature emphasizes the need for quality

assurance (Pearce and Lee, 2009). Therefore, analysis

features for reviewing exams are an integral part of

the concept. Furthermore, there is usually no (formal)

training for examiners and observers. The knowledge

of how to create the log is often passed on from the

examiner to the observer just before an exam, and the

examiner got their knowledge in the same way. Hence,

special support for novices is needed. In particular, the

form proposed in the concept and integrating manda-

tory steps may help unexperienced observers to create

high quality logs.

The developed prototype so far focuses on sup-

porting the observer and only implements essential

features (RQ3). The prototype has to compete with

log creation in standard office programs and also with

handwriting on paper, where special symbols can be

easily added. Probably the prototype will be compara-

ble or outperform standard office programs based on

the provided shortcuts. Still, the special, innovative

features may provide significant advantages over the

other two approaches currently used in practice. An

evaluation in an authentic exam setting has not yet

been possible, because of the sensitivity of these sce-

narios, which pose high demands on a prototype, and

because it is not easy to find examiners for mock oral

exams. Nevertheless, it was well received in the two

evaluations. Therefore, the proposed concept serves as

a good basis for the many features that still need to be

implemented for a ready-to-use product.

Overall, the potential benefits of analyzing the log

data is still uncovered. The interviewees rarely came

up with ideas to use the results or how (assessment)

analytics could be beneficial to improve this type of

assessment. This indicates a potential gap and allows

for possible improvements in future research.

8 LIMITATIONS

The concept is primarily based on the interviews and

their qualitative analysis. Therefore, the inherent limi-

tations of qualitative research must be acknowledged.

The reports of the current practice of oral exam are

based on experiences of the examiners and observers.

Here, two limitations need to be considered. First,

the interview study included 17 persons from Ger-

man higher education institutions, mainly from STEM

fields. Therefore, the results may be biased towards

national or domain specific aspects. However, the inter-

view included people with different backgrounds such

as language studies and educational sciences, which

broadened the view and led to additional ideas and

features. There was also a saturation of different ideas

and oral examination processes. To meet field spe-

cific requirements, experts in these fields would need

to be consulted. Second, the discussed legal regula-

tions/requirements are subject to Germany. Different

countries and/or universities may have different reg-

ulations. Still, there are likely many similarities that

can be made configurable in the prototype. For ex-

ample, voice recording, transcription, and automatic

summarization may be optional and/or only available

with explicit student consent. It is assumed that this

fact does not limit generalizability.

The final evaluation of the concept had a small

number of participants. Note here, that in practice,

just five users are enough to identify the most serious

usability problems (cf. Nielsen and Landauer, 1993;

Lindgaard and Chattratichart, 2007). The final version

also needs to be evaluated in authentic exams.

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

591

9 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper presents the concept development of a sup-

port tool for oral exams. Based on a requirements

analysis by interviewing examiners and observers re-

quirements were collected. An initial design prototype

was developed to streamline the concept development

process. Based on the results, a concept has been devel-

oped that considers all phases of the exam (preparation,

execution, and review) and focuses on the execution

phase to support observers in STEM exams, but can

probably also be used in and extended to other disci-

plines with little effort. Based on the concept a proof-

of-concept prototype was implemented and evaluated.

The results indicate that the concept is generally well

received, does not lack significant features, and is a

good basis for further research.

There are many possible extensions to the concept

that have been suggested by participants in our stud-

ies. For the initial proof-of-concept prototype only an

essential fraction could be implemented. In particular,

a few minor bugs need to be fixed, placeholders need

to be replaced, which would be necessary for a fully

usable product. Furthermore, a separate, distinct ex-

aminer view that displays the current log, the elapsed

time and stored questions should be added.

The complete digital, structured logging of an oral

exam is fundamental to conducting assessment ana-

lytics. Because of a machine-readable database, the

prototype lays the foundation to built promising analyt-

ics features to support grading (in terms of reliability

and validity) and to optimize exams/questions in the re-

view phase. This also opens up possible extensions for

an examiner view, which can then use the stored data to

display covered topics and to recommend (rarely used

or good follow-up) questions. Such features would

not be possible without the structured recording of

exam data and the usage of a specialized tool and may

increase the reliability of oral exams.

Next steps include bug fixing, conducting case stud-

ies in authentic oral examinations, making the features

configurable, and researching additional features with

a focus on usability and assessment analytics. Further

research should also focus on examiners as stakehold-

ers, for example, by investigating different types of

visualizations of the log to support them in asking the

“right” questions and in the grading.

More information about the current state of the

EasyProtocol project and the software is available at

https://www.tel.ifi.lmu.de/software/easyprotocol/.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the study participants for their valu-

able input. This research was supported by the German

Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF),

grant number [16DHBKI013] (AIM@LMU).

REFERENCES

Abuzied, A. I. H. and Nabag, W. O. M. (2023). Structured

viva validity, reliability, and acceptability as an assess-

ment tool in health professions education: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMC medical education,

23(1):531.

Akimov, A. and Malin, M. (2020). When old becomes new: a

case study of oral examination as an online assessment

tool. Assess. Eval. High. Educ., 45(8):1205–1221.

Ally, S. (2024). Scheduling online oral assessments us-

ing an iterative algorithm: A profound software for

educational continuity. Interdisciplinary Journal of

Education Research, 6:1–11.

Baghdadchi, S., Phan, A., Sandoval, C., Qi, H., Lubarda,

M., and Delson, N. (2022). Student perceptions of

oral exams in undergraduate engineering classes and

implications for effective oral exam design. ASEE

Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings.

Bayley, T., Maclean, K. D. S., and Weidner, T. (2024). Back

to the future: Implementing large-scale oral exams.

Management Teaching Review.

Burke-Smalley, L. A. (2014). Using oral exams to assess

communication skills in business courses. BPCQ,

77(3):266–280.

Delson, N., Baghdadchi, S., Ghazinejad, M., Lubarda, M.,

Minnes, M., Phan, A., Schurgers, C., and Qi, H. (2022).

Can oral exams increase student performance and mo-

tivation? ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition.

Dicks, A. P., Lautens, M., Koroluk, K. J., and Skonieczny, S.

(2012). Undergraduate oral examinations in a univer-

sity organic chemistry curriculum. Journal of Chemical

Education, 89(12):1506–1510.

Ellis, C. (2013). Broadening the scope and increasing the

usefulness of learning analytics: The case for assess-

ment analytics. BJET, 44(4):662–664.

Fischer, J. D. (2022). Pr

¨

ufungsrecht. C.H.Beck, 8. edition.

Gharibyan, H. (2005). Assessing students’ knowledge: oral

exams vs. written tests. SIGCSE Bull., 37(3):143–147.

Hartmer, M. and Detmer, H., editors (2022). Hochschulrecht:

Ein Handbuch f

¨

ur die Praxis. Juris Zusatzmodul Justiz

Verwaltungsrecht. M

¨

uller, C.F., Heidelberg, 4. edition.

Hazen, H. (2020). Use of oral examinations to assess student

learning in the social sciences. Journal of Geography

in Higher Education, 44(4):592–607.

Heppner, C., Wienfort, N., and H

¨

artel, S. (2022). Die

m

¨

undliche Pr

¨

ufung in den juristischen Staatsexamina –

eine Blackbox mit Diskriminierungspotential. ZDRW,

9(1):23–40.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

592

Huxham, M., Campbell, F., and Westwood, J. (2012). Oral

versus written assessments: a test of student per-

formance and attitudes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ.,

37(1):125–136.

Jebing, Z., Egetenmeier, A., and Strickroth, S. (2024).

easyProtocol: Ein digitales Unterst

¨

utzungstool f

¨

ur

m

¨

undliche Pr

¨

ufungen. Proceedings of DELFI 2024.

Joughin, G. (1998). Dimensions of oral assessment. Assess.

Eval. High. Educ., 23(4):367–378.

Kang, D., Goico, S., Ghanbari, S., Bennallack, K. C., Pontes,

T., O’Brien, D. H., and Hargis, J. (2019). Providing an

oral examination as an authentic assessment in a large

section, undergraduate diversity class. IJ-SoTL, 13(2).

Kirkwood, A. and Price, L. (2008). Assessment and student

learning: a fundamental relationship and the role of

information and communication technologies. Open

Learn., 23(1):5–16.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy:

An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4):212–218.

Kuhn, K., Kersken, V., Reuter, B., Egger, N., and Zimmer-

mann, G. (2023). Measuring the accuracy of automatic

speech recognition solutions. TACCESS, 16(4):1–23.

Lindgaard, G. and Chattratichart, J. (2007). Usability testing:

What have we overlooked? In Proc. CHI, pages 1415–

1424, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Markulis, P. M. and Strang, D. R. (2008). Viva voce: Oral

exams as a teaching & learning experience. Develop-

ments in Business Simulation and Experiential Learn-

ing, (35).

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical

foundation, basic procedures and software solution.

Klagenfurt.

Memon, M. A., Joughin, G. R., and Memon, B. (2010). Oral

assessment and postgraduate medical examinations:

establishing conditions for validity, reliability and fair-

ness. Advances in health sciences education : theory

and practice, 15(2):277–289.

Mu, Z. and Marquis, F. (2023). Can oral examinations

replace written examinations? In Proc. SEFI.

Nallaya, S., Gentili, S., Weeks, S., and Baldock, K. (2024).

The validity, reliability, academic integrity and inte-

gration of oral assessments in higher education: A

systematic review. IIER, 34(2):629–646.

Nielsen, J. and Landauer, T. K. (1993). A mathematical

model of the finding of usability problems. In Proc.

CHI, pages 206–213, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Ohmann, P. (2019). An assessment of oral exams in intro-

ductory cs. In Proc. SIGCSE, page 613–619. ACM.

Pearce, G. and Lee, G. (2009). Viva voce (oral examina-

tion) as an assessment method. Journal of Marketing

Education, 31(2):120–130.

Reckinger, S. J. and Reckinger, S. M. (2022). A study of

the effects of oral proficiency exams in introductory

programming courses on underrepresented groups. In

Proc. SIGCSE, pages 633–639. ACM.

Siemens, G., Dawson, S., and Lynch, G. (2013). Improving

the quality and productivity of the higher education sec-

tor. Policy and Strategy for Systems-Level Deployment

of Learning Analytics. Canberra, Australia: SoLAR for

the Australian Office for Learning and Teaching, 31.

Strickroth, S. and Bry, F. (2022). The future of higher ed-

ucation is social and personalized! experience report

and perspectives. In Proc. CSEDU, volume 1, pages

389–396. INSTICC, SciTePress.

Strickroth, S. and Holzinger, F. (2022). Supporting the semi-

automatic feedback provisioning on programming as-

signments. In Proc. MIS4TEL, pages 13–19. Springer.

Strickroth, S. and Kiy, A. (2020). E-Assessment etablieren:

Auf dem Weg zu (dezentralen) E-Klausuren., pages 235–

255. Number 6 in Potsdamer Beitr

¨

age zur Hochschul-

forschung. Universit

¨

atsverlag Potsdam.

Strickroth, S. and Striewe, M. (2022). Building a Corpus of

Task-Based Grading and Feedback Systems for Learn-

ing and Teaching Programming. International Journal

of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 12(5):26–41.

Westhoff, K. and Hagemeister, C. (2014). Competence-

oriented oral examinations: objective and valid. Psy-

chol Test Assess Model., 4(56):319–331.

Willert, M. (2018). M

¨

undliche Pr

¨

ufung: Handreichung der

Pr

¨

ufungswerkstatt. https://www.zq.uni-mainz.de/files/

2018/08/9 Muendliche-Pruefung-durchfuehren.pdf.

Wollin-Giering, S., Hoffmann, M., H

¨

ofting, J., and Ventzke,

C. (2024). Automatic transcription of english and ger-

man qualitative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozial-

forschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 25.

EasyProtocol: Towards a Digital Tool to Support Educators in Oral Exams

593