Digital Transformation Framework Inspired by Organisational

Semiotics: An Analysis Based a Chinese SOE Manufacturer

Wenxuan Li

1

, Qi Li

1

and Yixuan Liu

2

1

Henley Business School, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, U.K.

2

Faculty of Arts, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Keywords: Digital Transformation, Organisational Semiotics, Organisational Onion, Strategic Alignments.

Abstract: This study examines the process of digital transformation (DT) in a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE)

using the Organisational Onion Model (OOM) alignment framework inspired by Organisational Semiotics

(OS). The research explores how alignments among technical, formal, and informal layers contribute to

successful DT. It proposed an OMM alignment model and applied in a case of a Chinese SOE manufacturer,

where strategic priorities initiated a top-down approach to adopt new digital systems and reengineer business

processes. These changes subsequently influenced organisational culture and employee engagement. Key

findings highlight the role of iterative adjustments and feedback loops in achieving alignment, emphasising

the interplay between strategy, culture, technology, and process. Three propositions are proposed: alignments

can occur at any stage of DT, can be led by different layers in both top-down and bottom-up directions, and

are facilitated by digital champions. While the study primarily focuses on the initial stages of DT, future

research is encouraged to explore complete DT journeys and identify additional elements in each

organisational layer to deepen understanding of alignment dynamics and their impacts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital transformation (DT) has emerged as a critical

driver of innovation and competitiveness across

industries. It refers to a strategic shift inspired by new

technologies within organisations to seize new

opportunities in a changing environment (McAfee,

2009). For example, many businesses have adopted

cloud computing to reduce operating costs by

transitioning from CAPEX to OPEX, while others

view generative AI as a mean to enhance service

capabilities and expand their business scope (Krishna,

2024). Even traditional industries like mass

manufacturing are gradually evolving their business

operations with the power of digital technology.

Data-driven decision making can help predict the

changes in market demands in the future and guide

the design of current production schedule.

However, DT is more than just a change in

technology, but also achieving an alignment between

technology and other non-technical aspects, such as

business process. Polakova (2023) pinpoints

misalignment between IT and business during the

process of DT tends to be a major factor causing the

failure of DT project. Thus, addressing these

challenges requires a holistic approach that aligns

technological advancements with organisational

goals, stakeholder needs, and cultural dynamics.

Inspired by Stamper (1993) and Liu and Li

(2015), Organisational Semiotics (OS), a theoretical

framework rooted in the study of signs and their

interpretation in organisational contexts, offers a

unique perspective for tackling these challenges. OS

provides valuable insights into how information

flows within an organisational. Especially,

organisational onion model (OOM), as an important

model in OS, offers a morphological view of an

organisation, conceptualises organisations as multi-

layered entities encompassing technical, formal and

informal parts. Achieving alignment among these

layers ensures coherence and sustainability in DT

efforts.

As extended research of Lie et al. (2017) which

pinpoints the alignment initiated from informal layer,

and then extended to technical and formal layers, this

research further discovers the IT-business alignment

process in a context of state-own manufacturer, in

order to understand the major stages and content.

Li, W., Li, Q. and Liu, Y.

Digital Transformation Framework Inspired by Organisational Semiotics: An Analysis Based a Chinese SOE Manufacturer.

DOI: 10.5220/0013423700003929

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 875-882

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

875

Specifically, this research will look into the

alignments took place among different layers and

component in the organisational context.

2 THEORETICAL

UNDERPINNINGS:

ORGANISATIONAL

SEMIOTICS AND

ORGANISATIONAL ONION

Organisational Semiotics (OS), as a doctrine of signs

in the context of organisations, offers an inspiring

perspective on understanding how information can be

delivered and comprehended within organisations

(Stamper, 1997). It highlights the making sense of

information not only depended on the physical media,

but also driven by the shared understanding, purposes

and social contexts. Then OS has been applied to

understand how an information system can be

adapted in an organisation, especially highlighting the

alignment between its technical and social systems

(Liu and Li, 2015).

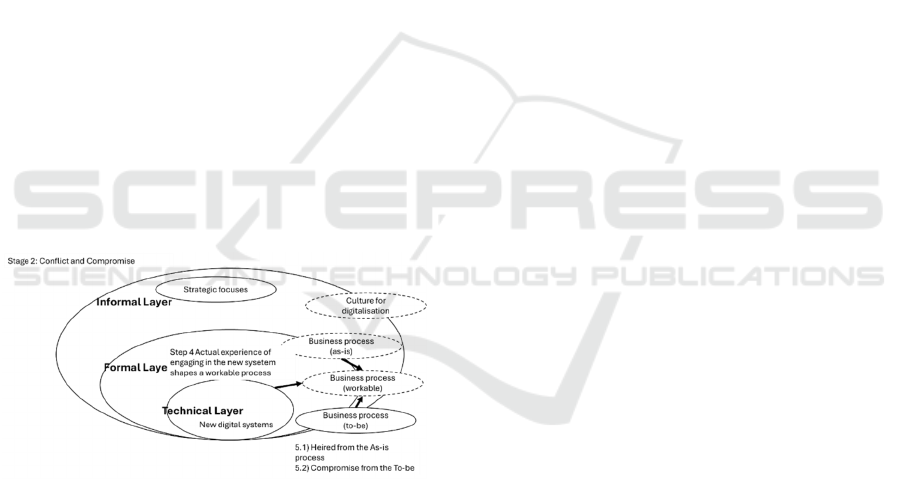

Organisational onion model (OOM), was derived

from the OS fundamental principle of IT and social

system alignment. It further contributes a

comprehensive view of understanding the structure of

a business organisation. As a breakthrough of

traditional view of an organisation by functions e.g.

organisational chart and structure, it defines an

organisational as a social system and divide it to three

layers by the nature of information content and

communication (Stamper, 1996). The inner layer is

technical layer, which refers to the hardware and

software for automating business activities and

facilitate communication within and between

organisations. It acts a fundamental media in an

organisation for exchanging information. The middle

layer is formal part, which refers the written rules and

procedure to guide people’s behaviours within an

organisation. It plays a key role to guide people’s

actions to make sure of technical systems for

achieving the best performance. The outer layer is

informal part, which refers the non-written rules in an

organisation, such as strategy and values. It can shape

people’s behaviour and understanding on the process

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Organisational Onion with alignments (derived

from Stamper, 1996 and Guo and Liu, 2023).

Inspired by Liu et al., (2016), OOM has been

applied in understanding IT-business alignment, by

highlighting the alignment between IT and business

process tends to a key contributor to the success of

DT. Business strategy also shapes this alignment in

long run, where the shift on technology and process

should serve the long-term objectives in business

strategy. In addition, Liu et al. (2017) specifies the

alignment among different layers of OOM in a top-

down pattern. It underscores that DT can be led by its

business strategy, and then lead to introducing new

technologies and new business processes. Therefore,

this research will further explore the process of

alignment among three layers and then understand its

sequence and focuses on each layer.

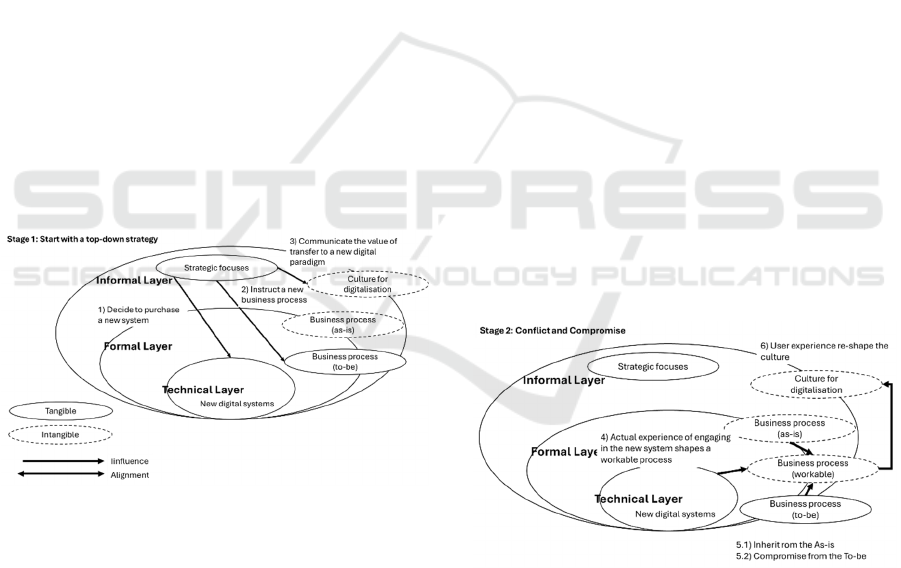

3 OOM ALIGNMENT MODEL

FOR DIGITAL

TRANSFORMATION

Based on OOM, an organisation can be viewed in

three layers, including technical, formal and informal.

Developed from Liu et al. (2017), the alignments can

also be defined into three categories (Figure 1).

Alignment 1 refers the informal-technical alignment,

where strategy or organisational culture leads the

introduction of new technology, and the development

of new technology impulse the emergence of new

business strategic focuses or new feature in

organisational culture. Alignment 2 refers to

informal-formal alignment, where a strategy shapes

business process or the evolution of business process

inspires the shift of strategic focuses. Alignment 3

refers to formal-technical alignment, where

introduction of new technology improves the

efficiency of business process. Alternatively, the

business process might need to the restructured in

order to lever the power of new technologies.

Alignment 4 refers to the internal alignment within

the informal layer, where the strategic focus(s) needs

to align with the organisational culture. In order

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

876

words, the proposed strategic focus(s) can be

recognised and accepted by the employees, and they

are willing to put in practice. Specially, the alignment

process can be divided into four stages.

3.1 Stage One: Top-down Approach

In Figure 2, DT can be initialised a strategic focus

from the top management team in a company e.g. to

control operational risks by enhancing the capacity of

data-driven decision making. Then the strategic

initiative can trigger the purchase of new

infrastructure and software for collecting, storing and

analysing data, for the purposes of ensuring the

available data for analysis (1). Meanwhile, the

strategic focus led to the design of a new business

process (2), which requires employees to input,

analyse, and retrieve information on the different

steps during the business process. Finally, strategic

focus will can be communicated to all employees via

announcement and employee training programme, in

order to let them understand the business value of

adapting data-driven decision making and enhance

their skills to make use of data analysis software and

follow the required business process (3). Overall, the

first stage demonstrates a top-down approach to lead

the changes on technical, formal and informal layers

with a strategic focus.

Figure 2: Top-down approach to digital transformation

across organisational layers.

3.2 Stage Two: Conflict and

Compromise

In Figure 3, based on the experience of using the

newly introduced system, the workable working

process, referring to working process implemented in

the reality, can be drifted away from the pre-defined

to-be process (4). Since the to-be process was

designed based on past experience and strategic

focus, which might not be fully in line with the real

scenario. For example, when it comes to identify

valuable customers, to-be process emphasises to

assess the default risks based on the quantified

financial data from customers. However, in the

reality, it is also necessary to consider the customers’

long-term strategy and business lifecycle in order to

measure their business potential. Thus, due to the

limitations on the technical layer, the business

process can be compromised from the to-be one to the

actual one (5.2). In addition, some successful and

useful practices will also be inherited from the as-is

process on which employees are very familiar and

proficient (5.1). Especially it defines the weight of

different measures when engaging them into decision

making. As a result, the actual working process can

be adapted from to-be process, also being influenced

by the actual experience of using the new system and

the successful practices from as-is process.

In this stage, employees can experience the

conflicts between to-be and workable process, and

compromise from as-is process by taking good

practices from the experience, which can shape their

understanding of the DT project (6). For example, the

perceived improvement on work efficiency can

motive them to recognise the value of DT, and

embrace the change, which is aligned with what was

promoted with the strategic focus in stage 1.

However, employees’ frustration caused the

limitations of technical system and mismatching

between technical system and business processes will

cause the resistance emotion, where employees

cannot recognise the value of data transformation and

then refuse to accept the change.

Figure 3: Conflict and Compromise in Digital Transfor-

mation across organisational layers.

3.3 Stage Three: Bottom-up Approach

With an increasing amount of experience to using and

being engaged in the new system, the feedback from

technical layers and formal layers can inspire an

evolution on the strategic focus (informal layer)

(Figure 4). Different from the top-down approach of

Digital Transformation Framework Inspired by Organisational Semiotics: An Analysis Based a Chinese SOE Manufacturer

877

being instructed by the strategic focus, the feedback

from technical layer can offer a different possible

strategic focus. For example, a technical feature e.g.

big data analysis can help identify new details which

have never been discovered before, and then it can

contribute a new insight to seize a business

opportunity (7). In addition, based on the experience

of conflicts and compromises in stage 2, although the

workable process might be different from pre-defined

to-be process, it can indicate some initiatives in the

to-be process might not be feasible in the reality, and

then strategic focus needs to be adjusted to be more

closed to the reality (8.1). Also, alternative changes in

the business process can be proposed in order to better

fulfil the strategic focus (8.2). Finally, with time goes

by, new knowledge accumulated in the practice of

working with the new system, and then it can

constitute some new approaches which can spark new

innovations on strategic focus (9). Therefore, this

model raises the following two propositions related to

timing and directions of alignment.

Proposition 1: Alignment(s) can be happened any

stages during the process of digital transformation. It

can be initialised at the start, but with different

maneuverers and adjustment in the following stages.

Proposition 2: Alignment(s) can be led by

different layers, including both directions of top-

down and bottom-up.

Figure 4: Bottom-Up Approach to Strategic Evolution in

Digital Transformation.

3.4 Stage Four: Strategic Alignment(s)

In the long term, other than directly promoting the

changes on technical and formal layers, it is important

to align the top management team’s strategic focuses

with culture perceived by all employees (Figure 5).

For example, the achievement of accepting and

implementing the new system should be recognised

and then awarded for encouraging more employees to

participate in the transformation. On the contrary, the

challenges and difficulties of engaging in the new

system should be identified and analyse, and then

more support and necessary adjustment need to be

allocated to help employees overcome the barriers. In

addition, skill gaps should also be investigated, and

appropriate training should be scheduled to empower

employees to make use of the new system (10).

Resulted from the alignment between strategic

focus and culture, employees can feel more motivated

to embrace the new technology (11.2), as well as

being engaged in the new working process (11.2).

Then increasing active employees’ engagement in

technical, formal and informal layer can contribute to

more feedback to inform and enrich the content of

strategic focus (10). It constitutes a loop of

continuous improvement to maximise the outcome of

DT.

Thus, this model raises another proposition based

on key actions in alignment. Proposition 3: Digital

Champions, from both roles of leadership and

operations, facilitate the alignment(s) among three

layers in long run.

Figure 5: Strategic Alignments for Continuous Improve-

ment in Digital Transformation.

4 ANALYSE A DIGITAL

TRANSFORMATION PROJECT

IN A CHINESE

MANUFACTURER VIA OOM

ALIGNMENT MODEL

Based on Piccolo and Roberto (2017), OOM can be

indirectly influenced by the general environment

where the organisation operates. The observation in

this research is based on a state-owned manufacturer

in China. Therefore, it is necessary to acknowledge

that the observation results can be shaped by the

Chinese SEO cultural context with the characteristics

of high-power distance culture, long-term orientation

and collectivism, based on Hofstede dimensions

(Giacobbe-Miller et al., 2003).

Observation was based on an ongoing DT project

of developing a digital production cluster with a

highlight of developing data-drive production system.

The data input was mainly based on the authors’

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

878

analysis and interpretation on project plan and

unstructured interview with the CIO in the

manufacturer.

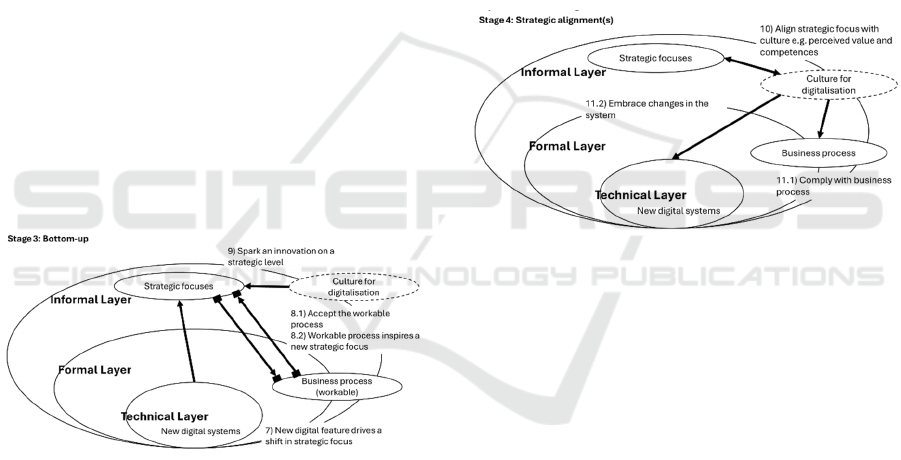

The observation mainly focuses on the first stage

of DT. It begins with a top-down strategy,

emphasising the need to establish a clear direction

and commitment from organisational leadership. This

stage focuses on the Technical IS layer, where the

decision to purchase new digital systems is made.

Such a decision is often driven by strategic priorities

that aim to enhance organisational efficiency and

competitiveness through technological

advancements. The introduction of these systems

serves as the foundation for subsequent changes in

business processes and organisational culture.

A key aspect of this stage is aligning the technical

implementation with broader organisational

objectives. Leadership plays a vital role in

communicating the rationale behind the adoption of

new systems, ensuring that the investment aligns with

the long-term vision of the organisation. By initiating

change at the technical level, this stage sets the

groundwork for reshaping the Formal IS and Informal

IS layers in subsequent stages. This structured,

hierarchical approach ensures that the DT process

begins with a solid technological foundation, guided

by strategic imperatives.

Figure 6: Step 1-3 in digital transformation.

4.1 Step 1 - Building a Digital

Foundation with Strategic

Investments

In the DT project of this Chinese engineering

equipment manufacturer, the decision to purchase a

new system was not merely a conventional

acquisition of isolated technological tools. Instead,

the organisation undertook a more ambitious

initiative: the construction of an entirely new smart

industrial city, built entirely on advanced digital

systems. This approach represents a comprehensive,

top-down strategy to establish a cutting-edge digital

infrastructure, aligning with the Technical IS layer in

the Organisational Onion model.

The creation of the smart industrial city reflects a

shift from traditional system procurement to a

systemic overhaul, where the entire operational and

organisational framework is designed around digital

technologies. This initiative integrates advanced

systems such as IoT, AI, and big data analytics into a

cohesive platform, enabling seamless digitalisation

across the enterprise. By constructing a new,

technology-driven ecosystem, the organisation not

only addressed its immediate operational needs but

also laid the groundwork for adaptive, intelligent

business processes and future scalability.

This strategic move exemplifies a luxury-level

approach to system acquisition, where the focus

extends beyond technical functionality to encompass

organisational alignment and transformation. The

smart industrial city serves as a foundational enabler

for subsequent stages of DT, including business

process reengineering (Formal IS) and cultural

adaptation to digital innovation (Informal IS). This

systemic perspective ensures that technical

advancements are integrated with organisational

objectives, fostering long-term value creation.

Through the construction of the smart industrial

city, the organisation established itself as a pioneer in

DT, leveraging an ambitious technical foundation to

drive comprehensive changes across its operations,

processes, and culture. This approach underscores the

critical role of strategic, large-scale system adoption

in achieving alignment and enabling the transition

toward an intelligent, digitally enabled future.

4.2 Step 2 - Redesigning Business

Processes for Digital Integration

The phase of instructing a new business process

focuses on the systematic reengineering and

optimisation of organisational workflows to align

with the capabilities of newly adopted digital

systems. This stage involves the redesign and

integration of core business processes, ensuring

seamless coordination across organisational units

while leveraging advanced digital tools for execution.

A key aspect of this phase is process integration,

where traditional linear workflows are transformed

into interconnected, data-driven processes. By

employing frameworks such as the RACI model, the

organisation establishes clear roles and

responsibilities, ensuring transparency and

accountability in process execution. This structured

approach facilitates the alignment of strategic

objectives with operational outcomes, creating a

robust foundation for DT.

Digital Transformation Framework Inspired by Organisational Semiotics: An Analysis Based a Chinese SOE Manufacturer

879

The integration of IT and OT technologies, along

with the adoption of Industry 4.0 principles, further

supports the dynamic realignment of business

processes. Data-driven mechanisms, such as KPI

monitoring and intelligent control towers, enable real-

time visibility and continuous optimisation of

workflows. This ensures that new business processes

are not only efficient but also adaptable to changing

operational demands.

Moreover, the restructured processes integrate

product design, supply chain management, and

manufacturing operations into a unified value chain.

Systems such as BOM and MES establish seamless

connections across planning, execution, and feedback

loops, enabling the realisation of an end-to-end digital

ecosystem. This holistic approach to business process

design ensures that operational efficiency is

maximised while fostering a culture of continuous

improvement and responsiveness to external and

internal challenges.

4.3 Step 3 - Driving Cultural and

Managerial Shifts Through Data

Insights drawn from an interview with the

organisation's Chief Information Officer (CIO)

emphasise that the essence of DT lies in shifting from

experience-based to data-driven decision-making

across all organisational levels. The CIO highlighted

that digitalisation is not merely about adopting

advanced systems or platforms but fundamentally

about transforming the enterprise's decision-making

processes. This shift enables organisations to make

more objective and precise decisions, enhancing their

ability to navigate complex market environments.

The CIO provided a practical example, explaining

how, in the past, sales personnel relied on subjective

experience to evaluate customer credit, predict

payment capabilities, and assess sales costs and

returns. While such methods could be effective in

specific scenarios, they often lacked scientific rigour

and carried inherent limitations due to the variability

of individual experience. Through digitalisation, the

organisation systematically collects and analyses data

such as customer credit reports and annual

statements, building accurate, data-based customer

models. These models provide objective insights,

allowing the organisation to manage risks more

effectively and make more reliable business

decisions.

The interview further highlighted how DT

impacts employees at different levels of the

organisation. For senior management, the value lies

in accessing comprehensive, data-driven insights that

support strategic decision-making. Middle-level

managers benefit from improved visibility and real-

time monitoring of operational performance, enabling

them to adjust strategies effectively. Grassroots

employees experience increased efficiency through

automation and reduced manual workload, allowing

them to focus on critical tasks and improve

productivity.

The CIO also acknowledged the challenges of

embedding digitalisation into the organisational

culture. Resistance to change and the reliance on

traditional decision-making methods can impede the

adoption of a data-driven paradigm. To address this,

the organisation prioritises training programs, cross-

departmental collaboration, and the establishment of

unified data standards. These initiatives aim to build

trust in digital tools and foster a culture of innovation

that aligns with the organisation's strategic focus.

This analysis demonstrates how the organisation

leverages digitalisation not only as a technological

advancement but also as a cultural and managerial

shift. By effectively communicating the value of DT

and aligning it with both strategic objectives and

employee engagement, the organisation lays a strong

foundation for sustained innovation and long-term

competitiveness.

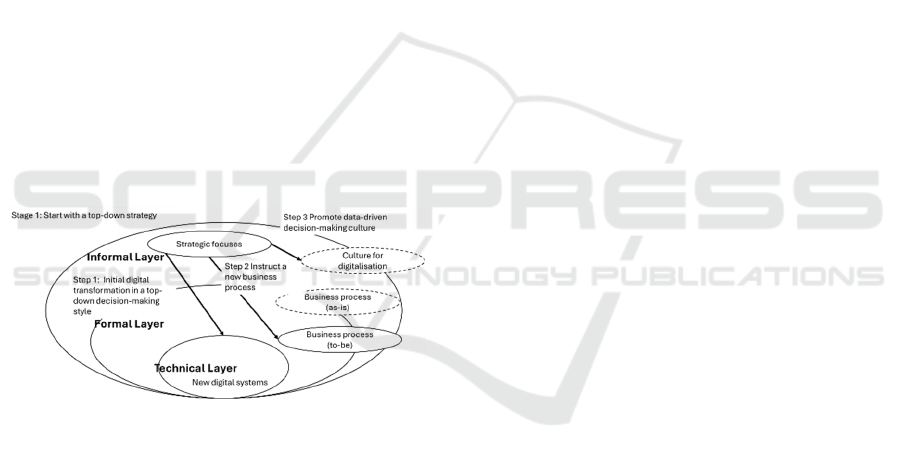

4.4 Step 4 & 5 - Achieving Alignment

Through Iterative Adjustments

In the organisation’s DT journey, the introduction of

new technologies (Technical IS) necessitated

iterative adjustments to align existing business

processes ("as-is") with the envisioned target

processes ("to-be"). This process was characterised

by resolving conflicts through optimisation and

compromise, leading to the development of

functional "workable processes" that balanced

technical capabilities with operational realities.

One significant challenge the organisation faced

involved the integration of its production planning

and execution systems. Gaps between the enterprise

resource planning (ERP) system and the

manufacturing execution system (MES) created

inefficiencies, particularly in synchronising

production schedules with real-time operational data.

For example, discrepancies in data flow between

these systems prevented the seamless adaptation of

production schedules to actual shop floor conditions.

To address this, the organisation restructured its

workflows, prioritising the synchronisation of ERP-

generated plans with feedback from MES. This

adjustment ensured that existing processes adapted to

the new digital framework, enabling smoother

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

880

operations and better alignment with technological

advancements.

The organisation also encountered challenges in

achieving the ambitious goals set for its target

processes. These "to-be" processes envisioned a fully

integrated factory system that unified factory layout,

material flows, and production systems under a

comprehensive digital blueprint. However, practical

constraints such as incomplete data connectivity and

limited IT-OT (information technology and

operational technology) integration necessitated

compromises. For instance, the initial plan to

establish real-time feedback loops between digital

twins and production lines had to be revised. Instead,

the organisation adopted a phased approach,

achieving partial connectivity milestones while

continuing to refine its systems. This compromise

ensured that progress was maintained while

addressing the limitations of current technology and

resources.

Through these adjustments, the organisation

successfully transformed its business processes into

"workable processes" that aligned with both its

operational needs and DT goals. These iterative

refinements allowed the organisation to optimise

resource allocation, enhance efficiency, and reduce

systemic bottlenecks, demonstrating the importance

of flexibility and compromise in navigating the

complexities of large-scale DT.

Figure 7: Step 4-5 in digital transformation.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND

FURTHER STUDY

This research focuses on the alignments among three

layers of OMM during the process of DT. Developed

from Liu et al. (2017), it proposed an OOM alignment

framework to highlights the alignments among

different components in technical, formal and

informal layers, and explained the process where

alignments took place. Overall, the DT can be

initialised by the strategic focuses, and then lead to

the change in IT systems, formal processes, culture to

embrace DT (stage 1). Based on the actual use of new

IT systems, employees will adopt a workable process,

derived from as-is process and the actual experience

of using the new IT systems, which can further shape

the culture of digitalisation within the organisation

e.g. acceptance or resistance (stage 2). In the stage 3,

the feedback from each layer, such as new features

from IT systems, user experience of being engaged in

the workable process, and new digitalisation culture,

can help influence the strategic focuses. Finally, the

shift of strategic focus will re-align with the

digitalisation culture in order to promote more

employees’ acceptance on the new IT system and

compliance with the new work process (stage 4).

Then three highlighted propositions about

alignments in DT process can be summarised as

follows.

Proposition 1: Alignment(s) can be happened any

stages during the process of digital transformation. It

can be initialised at the start, but with different

maneuverers and adjustment in the following stages.

Proposition 2: Alignment(s) can be led by

different layers, including both directions of top-

down and bottom-up.

Proposition 3: Digital champions, from both roles

of leadership and operations, facilitate the

alignment(s) among three layers in long run.

However, the limitations in this research can be

articulated below, followed by suggestions for future

studies.

Firstly, although a 4-stage OMM-inspired

alignment framework has been proposed in this

research, the interview in the Chinese SOE merely

illustrated the first and second stage. Thus, stage 3-4

has not been witnessed in a real case. In order words,

this research has not yet found evidence to support the

process of stage 2-4 which were developed based on

the reasoning on the original OMM and OS theories.

For future studies, they can consider conducting a

longitudinal study, either by analysing a complete

process of a DT case, or by following a company

through its complete journey of DT. Then they will

be able to articulate how the alignment process

happened in a real scenario and justify if it follows the

propositions raised in this research.

Secondly, although this research identified some

elements in each layer of OMM, such as strategic

focuses from top management team and digitalisation

culture conveyed by employees, more elements can

be specified on different layers when more in-depth

interviews have been incorporated in this research in

order to understand the challenges the SOE

encountered in the reality. For example, OOM

Digital Transformation Framework Inspired by Organisational Semiotics: An Analysis Based a Chinese SOE Manufacturer

881

alignment model indicates influenced by as-is process

and experience of using new IT systems, the

employees will adopt a workable process, which is

different from the predefined the to-be process.

However, in the reality, there might be different

process where some of them can be easily complied

and some not, and then they could influence the

digitalisation culture on different extents. Then the

conflicts and compromises might be happened more

on some processes than others, which can be further

discovered in the future studies.

REFERENCES

Giacobbe-Miller, J. K., Miller, D. J., Zhang, W., &

Victorov, V. I. (2003). Country and organizational-

level adaptation to foreign workplace ideologies: A

comparative study of distributive justice values in

China, Russia, and the United States. Journal of

International Business Studies, 34(4), 389–406.

Guo, H., & Liu, K. (2024). The chasm of technology

innovation in digital transformation: A study from the

perspective of transformation informatics. Business,

Management and Economics. IntechOpen.

https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.111793

Liu, K., & Li, W. (2015). Organisational semiotics and

business informatics. Routledge.

Krishna, S. H., Kumar, G. P., Reddy, Y. M., Ayarekar, S.,

& Lourens, M. (2024, May). Generative AI in business

analytics by digital transformation of artificial

intelligence techniques. In 2024 International

Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences

and Engineering (IC3SE) (pp. 1532–1536). IEEE.

Li, W., Liu, K., Tang, Y., & Belitski, M. (2017). E-

leadership for SMEs in the digital age. In F. X. de Faria,

C. A. Cruz, & C. Vieira (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook

of managing continuous business transformation (pp.

375–416). Palgrave Macmillan.

McAfee, A. (2009). Enterprise 2.0: New collaborative tools

for your organization's toughest challenges. Harvard

Business Press.

Piccolo, L. S. G., & Pereira, R. (2017). Culture-based

artefacts to inform ICT design: Foundations and

practice. AI & Society, 34(3), 437–453.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0743-2

Poláková-Kersten, M., Khanagha, S., van den Hooff, B., &

Khapova, S. N. (2023). Digital transformation in high-

reliability organizations: A longitudinal study of the

micro-foundations of failure. The Journal of Strategic

Information Systems, 32(1), Article 101756.

Stamper, R. (1996). Signs, information, norms, and systems.

In B. Holmqvist (Ed.), Signs of work (pp. 349–399).

Elsevier Science.

Stamper, R. (1997). Organisational semiotics. In J. Mingers

& F. Stowell (Eds.), Information systems: An emerging

discipline (pp. 267–283). McGraw-Hill.

Stamper, R. K. (1993, September). A semiotic theory of

information and information systems. In Joint

ICL/University of Newcastle Seminar on the Teaching

of Computer Science 1993: Part IX: Information (pp.

1–33). University of Newcastle.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

882