Analysing Italian Historical Small Towns: A Cultural and

Geographic Mosaic of Identity

Cristina Ciliberto, Giuseppe Ioppolo, Giuseppe Caristi and Grazia Calabrò

Department of Economics, University of Messina, Via dei Verdi 75, Messina, Italy

Keywords: Tourism, Historical Small Towns, SWOT, Sustainable Tourism Development.

Abstract: The recent increase in the Tourism sector has underlined its economic centrality, contributing to 9,1% of

global GDP in 2023. The European Union holds a significant position, counting more than 50% of

international arrivals. This, in turn, can be translated into considerable economic effects that positively affect

the member states. Among such states, Italy has been ranked in the top five international destinations,

registering over 57 million tourist inflows. Such an increase has been driven by affluence in major cities and

the modern trend of rediscovering historical small towns (HST). This research aims to analyse the components

of this trend, underscoring the geographical position and features of the HSTs throughout the Italian territory.

Moreover, a descriptive analysis with quantitative data and a SWOT analysis will be conducted to assess their

distribution through the Italian territory and their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Preliminary findings reveal that regions such as Central Italy host the highest concentration of villages, while

climate change and depopulation threaten their viability. By analysing these HSTs, the study aims to inform

strategic planning for sustainable tourism development, enhancing local identities and preserving cultural

heritage while positioning these areas as viable alternatives in the global tourism landscape.

1 INTRODUCTION

Tourism constitutes a pivotal force in driving

economic growth and job creation while serving as a

social need (Agovino et al., 2017; Streimikiene et al.,

2021). Streimikiene et al. (2021) recognize this sector

as one of the most important economic sectors in

leading countries worldwide, contributing

approximately 9.1% to the global Gross Domestic

Product (GDP) (nearly 10 trillion U.S. dollars)

(Statista 2023). In this international perspective, the

European Union (EU) holds a dominant position

(Roman et al., 2020), counting over 50% of global

international tourist arrivals, with over 700 million

people visiting the region (Statista, 2024). This

substantial number of tourists can be translated into a

significant economic effect across the EU countries,

as the travel and tourism sector contributed more than

two trillion euros to the continent’s GDP that year

(Statista, 2024). For this reason, the EU tourism

policy seeks to provide directives and regulations for

the member states to maintain the status of the top

global destination while transforming it into a

sustainable place to visit, considering its social and

environmental dimensions (European Commission,

2024). Among EU countries, Italy holds a significant

position, ranking in the top five international tourist

destinations, with 57.3 million arrivals in 2023

(Castellano et al., 2020; ISTAT, 2024; Statista, 2023).

Here, tourism represents one of the core economic

sectors, offering a considerable amount of job

opportunities and contributing to 18% of the domestic

GDP (in 2023) (OECD, 2010; ISTAT, 2024). In this

context, the latest measurements show an increase in

visitor numbers higher than the national average

(9.5%). Such increments regarded some Italian

regions such as Lazio (25.3%), Lombardy (16.8%),

Sicily (13.9%), Campania (13.3%), and Aosta Valley

(11%) (Italian Ministry of Tourism, 2023). According

to Barbera et al. (2022), two main factors have driven

such increases: the tourist flows in regional capitals

as Rome, Milan, Palermo, Naples, and Aosta and the

modern trend of rediscovering Historical Small

Towns (HST). Such a trend embraces the quest for

authenticity, including cultural and social identities,

traditions, memories, local features, and rural

landscapes, prompting local, national, and European

authorities to address evolving tourism demands

(Garau, 2015). This, in turn, has significantly

impacted Italian HSTs, elevating them as emerging

Ciliberto, C., Ioppolo, G., Caristi, G. and Calabrò, G.

Analysing Italian Historical Small Towns: A Cultural and Geographic Mosaic of Identity.

DOI: 10.5220/0013426600003956

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2025), pages 217-223

ISBN: 978-989-758-748-1; ISSN: 2184-5891

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

217

spots and positioning them as appealing alternatives

to major cultural cities (Biconne, 2020). Many of

these villages in Italy are known as “Borghi” or HSTs.

They typically have no more than 5,000 residents and,

according to the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and

Cultural Activities and Tourism (MIBACT), possess

“a valuable cultural heritage, whose preservation and

enhancement are highly significant for the national

system, as they embody authenticity, uniqueness, and

beauty distinctive qualities of Italy’s tourism appeal”

(Bizzarri & Micera, 2021). Despite the growing

interest, there is a lack of identification and

categorizing of Italian villages and their potential. To

fill this gap, this study will provide an overview of the

typologies and related features of Italian HSTs. In

addition, a SWOT analysis can be conducted to

identify internal factors, such as strengths and

weaknesses, and external factors, like opportunities

and threats, that can enable or impede the historical

small-town mission.

To this end, preliminary results will provide

insights to pave the way for further HSTs

valorizations.

2 METHODOLOGY

This analysis employs a mixed approach, employing

a descriptive study with quantitative data and a

qualitative analysis through the SWOT Analysis. The

dataset used for the identification of each “borgo”

includes information from the International

Federation “Les Villages plus belle de la Terre” and

“I Borghi più Belli d’Italia” together with data from

multiple sources, including the Italian National

Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) (Istituto Nazionale di

Statistica in Italian) and Statista, Google Maps and

geographical information systems (GIS). The data has

been collected on the year of observation (2023) as

well as the geographical zone (NUTS1), region

(NUTS2), and province (NUTS3) according to the

Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics

(NUTS) established with the Regulation (EC) No

1059/2003 (European Commission 2023). The

dataset analysis allows the assessment of the number

per region. Hence, the HSTs were classified based on

geographical position first and geographical features

second. In the first phase, the HSTs distribution was

performed, and the sites were according to the

geographical classification provided by ISTAT

(north, centre, south, and island) (ISTAT, 2023).

Then, to deepen the analysis, a further classification

considered the geographical features

, individuating

three categories: Mountain HSTs (MB), referring to

sites located at a certain altitude above 600 meters

above sea level; Coastal HSTs (CB) if it has a direct

connection with sea or a large lake; Rural HSTs (RB)

if it is characterized by hilly territory, low population

density (less than 200 inhabitants per square

kilometre) and sparse distribution of housing. The

different territorial identities reflect different focuses

in terms of economy, culture, and technology

(Capello, 2019). For this reason, understanding the

diverse advantages and barriers characterizing the

various typologies of the HSTs can provide helpful

information to foster effective policies and support

local development. At this stage, a SWOT has been

conducted, highlighting the strengths, weaknesses,

opportunities, and threats of each category of the

HSTs (Almutairi et al., 2022; Bisu et al., 2024).

(Witara et al., 2024). This, in turn, aims to provide a

clearer understanding of HSTs distribution and the

specific challenges that must be addressed to enhance

valorisation, supporting strategic planning and

decision-making processes effectively.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the International Federation “Les Plus

Beaux Villages de la Terre” (2024), Italy with 363

villages, holds the first position in terms of number of

villages, followed by France (178), Spain (116),

Japan (58), Switzerland and Lichstein (50) and

Wallonia (32). Considering the HSTs’ geographic

position, it has been possible to notice a

heterogeneous distribution among the different areas

of the Italian territory has been observed (Table 1).

These preliminary results highlight that “Central

Italy” has the largest number of villages, with 149.

Here, regions like Tuscany, Umbria, and Marche are

known for their well-preserved medieval and

Renaissance villages (such as San Giminiano and

Urbino), often considered pillars of tourism and

regional identity. Differently, Northern Italy shows a

varied distribution of villages, totalling 131. In such

areas, regions such as Liguria and Lombardy present

the highest number of villages, perhaps due to the

development of many small, isolated villages, often

perched on cliffs or nestled in valleys. In contrast,

industrialized regions like Veneto and Emilia-

Romagna also maintain a considerable number of

HSTs, reflecting a balance between urban

development and rural preservation in northern Italy.

Moreover, the southern part of Italy shows fewer

people, with only 50 HSTs. This lower number may

reflect the South's historical economic and industrial

challenges and the migration trends of people

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

218

Table 1 - Distribution of villages in Italy, Source: I Borghi

più belli d’Italia, Elaboration: Authors.

Region Numbe

r

of HSTs

North of Ital

y

Aosta Valle

y

3

Piedmont 19

Lombard

y

26

Veneto 11

Trentino-South

T

y

rol

16

Friuli Venezia

Giulia

13

Li

g

uria 27

Emilia Romagna 16

Central Ital

y

Tuscan

y

30

Marche 31

Umbria 32

Lazio 26

Abruzzo 26

Molise 4

South of Ital

y

Campania 13

A

p

ulia 13

Basilicata 9

Calabria 15

Islands

Sicil

y

24

Sardinia 9

(approximately 1.1 million) moving from southern

regions to northern regions for better economic

opportunities, resulting in rural depopulation

(Lepore, 2020; ISTAT, 2021). Lastly, the Italian

Islands (Sicily and Sardinia) have a total of 33 HSTs,

with a greater concentration in Sicily (24). This could

be due to Sicily’s historical significance as a cultural

and trade crossroads, which led to the establishment

of numerous settlements. In Sardinia, the context is

slightly different, as social and economic

development may hinder the valorization process

(Garau et al., 2019). Despite its unique landscapes

and panoramas, this region ranks among the lowest in

Italy for the number of sites, placing third from the

bottom alongside Basilicata. These preliminary

findings pave the way for a further classification that

integrates geographical location and geographical

features, leading to the following categorization

(Figure 1):

This, in turn, enables a better understanding of local

identities, distinguishing the HSTs by geographical

position and features underlining historical and

cultural practices inherent to each area. By analysing

the distribution of the HSTs and considering such

classification (Table 2), it has been possible to gain a

picture of the Italian panorama.

Table 2 - Numerical distribution of Italian HSTs, Source:

Authors.

Area MB CB RB Total

North 92 17 31 140

Centre 95 16 26 137

South 42 14 3 59

Islands 20 5 2 27

Total 249 52 62 363

The prominent presence of MB and RB in northern

and central Italy likely reflects the historical

settlement patterns. These areas are characterized by

communities that have adapted to the challenges

related to transportation routes and economic and

social infrastructure, demonstrating impressive

resilience and adapting to challenging and shifting

natural conditions (Ehrlich et al., 2021; Wyss et al.,

2022). This adaptation is evident in how these

communities have maintained their cultural heritage

and sustainable practices over generations. From this

perspective, these HSTs offer attractions that leverage

mountain features, aligning with recent experiential

tourist needs by promoting winter sports such as

hiking and skiing and providing opportunities for

adventure (Steiger et al., 2024). In contrast, CB is

typically favoured for its sea views and recreational

opportunities next to the sea. Here, tourists often

gravitate towards relaxing pursuits such as

sunbathing, sailing, and nautical sports (European

Figure 1. Categories of HSTs Source: Authors.

Analysing Italian Historical Small Towns: A Cultural and Geographic Mosaic of Identity

219

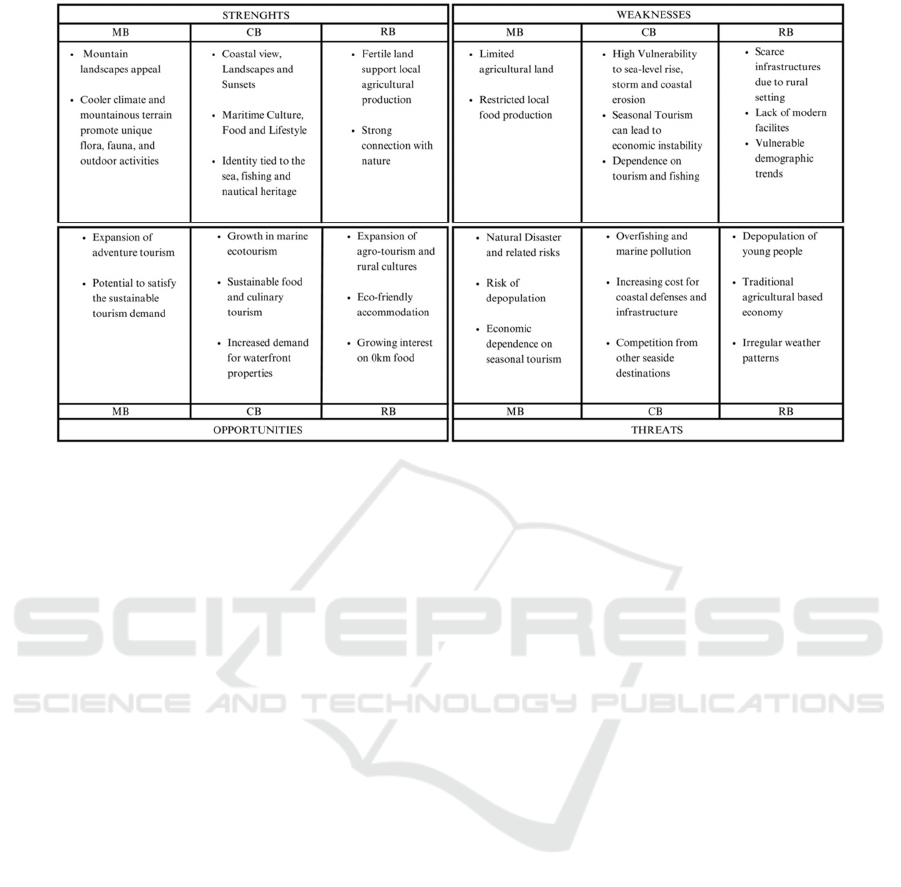

Figure 2. SWOT Analysis of Italian HST. Source: Authors.

Commission, 2024b). However, more than such

information is needed. A SWOT analysis has been

employed, underlining strengths, weaknesses,

opportunities, and threats (Figure 2).

The SWOT analysis of HSTs reveals distinct

patterns across mountain, coastal, and rural settings,

each presenting challenges and opportunities for

sustainable development and preservation. As

Bitušíková (2021) observed, these settlements often

serve as repositories of cultural heritage.

Mountain-based historical towns benefit from

their unique landscape heritage and climatic

conditions, which increasingly align with growing

adventure tourism trends (Apollo and Andreychouk

2022). These locations often preserve traditional

architectural elements and cultural practices that have

evolved in response to their geographical constraints.

However, they face significant challenges related to

accessibility and economic sustainability, particularly

during off-peak seasons. Research by Romeo et al.,

(2020) indicates that mountain communities often

struggle with limited agricultural capacity and

restricted local food production, leading to increased

dependence on external supply chains.

Maritime culture and heritage of coastal historical

towns create unique opportunities for tourism

(Ounanian et al., 2021). However, these communities

face escalating challenges from climate change

impacts. According to Major and Juhola (2021),

coastal settlements are increasingly vulnerable to

storm surges and rising sea levels, necessitating

substantial investments in protective infrastructure.

The seasonal nature of tourism in these areas, while

providing essential economic benefits, also creates

significant social and infrastructural pressures during

peak periods.

Rural historical towns possess fertile agricultural

land and strong connections to nature; however, they

face significant demographic challenges. Eurostat

(2024) article on rural communities highlights how

the lack of modern infrastructure and limited

economic opportunities contribute to youth

outmigration. However, these areas are experiencing

renewed interest through the growing popularity of

agritourism and eco-friendly travel experiences

(Ndhlovu and Dube, 2024).

Across all three typologies, common threads

emerge regarding the opportunities for sustainable

tourism development. The post-pandemic shift

toward experiential and authentic travel experiences

has created new possibilities for these historical

settlements (Sunder and Dixit, 2023). However, this

opportunity must be balanced against the threat of

overtourism and the need to preserve local cultural

identity (Capocchi et al., 2019; Dodds & Butler,

2019).

The analysis suggests that successful

development strategies must address three key areas:

infrastructure modernization, economic

diversification, and environmental resilience. The

future viability of HSTs depends on their ability to

adapt to changing demographic and economic

patterns while preserving their unique cultural and

architectural heritage (Božić et al., 2019).

Analyzing these SWOT Factors has played an

essential role in understanding internal and external

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

220

elements interacting with each HSTs category. In this

sense, the natural landscapes of the Italian HSTs

represent a common strength. Indeed, Skowronek et

al. (2018) emphasized the landscape’s role, making

them a critical component in pursuing sustainable

tourism, balancing and preserving natural and cultural

heritage with social needs and economic interests.

Achieving this balance depends on carefully

assessing how landscapes are described, evolve, and

manage their resources effectively (Skowronek et al.,

2018).

In addition, the mild climate needs to be

considered, as it fosters seasonal tourism in winter,

mainly MB; in summer, CB, autumn, and spring, RB

is the leading destination. This, in turn, creates the

basis for the latest opportunities in sustainable

tourism, encompassing ecological, financial, societal,

and cultural development elements (Pan et al., 2018).

Thus, it contributes to achieving environmental

sustainability, economic viability, and ethical and

social equity (Pan et al., 2018).

Furthermore, local, seasonal products are

experiencing renewed appreciation, and the process

involved in their creation enhances their significance

in modern contexts (Gonda et al., 2021). Indeed,

Choe & Kim (2018) emphasized that tourists seek

experiences that broaden their knowledge or cultural

understanding through local products. This might

include discovering new cooking methods, exploring

the origins of specific ingredients, or uncovering the

stories behind traditional dishes (Choe & Kim, 2018).

However, difficulties do exist. The effects of climate

change led to hydrological and meteorological

irregularities (Mokhov et al., 2022), resulting in

extreme weather events and unpredictable rainfall

patterns, posing significant risks to natural

ecosystems but also to social and economic ones

(European Commission, 2024a). Moreover, the trend

of younger mountain people migrating to cities and

other countries is leading to the depopulation of

mountainous regions and the consequent economic

decline (Rey, 2015). Furthermore, phenomenon such

as overtourism can bring negative effects, such as

excessive number of visitors, disruptive or

inappropriate behavior by tourists, tension between

locals and tourists, overcrowding, pressure on

infrastructure, loss of cultural authenticity,

diminished amenities, a decline in residents' quality

of life, and reduced tourists experiences (Dodds &

Butler, 2019). In this regard, technological solutions

are widely considered essential for addressing, or at

least reducing, the effects of overtourism and its

adverse impacts on destinations (Gretzel, 2021). This,

in turn, can lead to the development of an e-tourism

system where digitalization is integrated into every

phase of the travel industry (Hamid et al., 2021).

Moreover, implementing digital solutions such as

digital platforms and e-commerce for local artisans

could facilitate the trading of local businesses,

improving the overall local markets and providing

users with secure, reliable, and efficient solutions

(Kalyan et al., 2024). From this perspective, an

essential element is represented by the collaboration

with local institutions, which allows HSTs to pool

resources, secure shared infrastructure funding, and

build collective resilience to sustain growth and

adaptability in the face of actual and future

challenges.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Harnessing the potential of Italian HSTs has emerged

as a significant catalyst for national tourism,

connecting local communities with tourists

worldwide. The descriptive analysis of these HST

reveals 363 Italian sites, which exhibit a

heterogeneous distribution primarily concentrated in

central and northern regions. This, in turn, reflects the

nation’s historical significance as a hearth of Italian

culture and heritage, where many traditional practices

and local customs have flourished over centuries.

Moreover, examining these HSTs’ geographical

position and features provided a picture of how they

are distributed across Italian territory. In this sense, a

SWOT analysis identified strengths and

opportunities, weaknesses and potential threats. The

evaluation of the sites distribution and the assessment

of their critical components leads to preliminary

results. This, in turn, can provide helpful information

so that public and private stakeholders can improve

strategies to guide and guide a better decision-making

process to bolster local and national tourism. In

conclusion, promoting and valorizing local identities

and the historical significance of these HSTs can

effectively position these areas as attractive

destinations that celebrate and preserve Italian

traditions. Such initiatives enable better visibility and

viability, ensuring the maintenance of their status as

integral components of international tourism. The

collaboration among various stakeholders, including

local governments, tourism boards, and community

organizations, can create a more cohesive approach to

promoting these destinations while ensuring their

cultural heritage is respected and preserved for future

generations. These preliminary results will pave the

way for initiatives designed to elevate the visibility

and sustainability of Italian “Borghi” and solidify

Analysing Italian Historical Small Towns: A Cultural and Geographic Mosaic of Identity

221

their role as critical elements in national and

international tourism strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has received funding from PNRR -

Missione 4, Componente 2, Investimento 1.1 - Bando

Prin 2022 - Decreto Direttoriale n. 104 del 02-02-

2022- Progetto “H-SMA-CE: a decision support

system for circular economy transition” CUP

J53D23009390006 - codice identificativo

2022JZLL7J.

REFERENCES

Agovino, M., Casaccia, M., Garofalo, A., & Marchesano,

K. (2017). Tourism and disability in Italy. Limits and

opportunities. Tourism management perspectives, 23,

58-67.

Almutairi, K., Hosseini Dehshiri, S. J., Hosseini Dehshiri,

S. S., Mostafaeipour, A., Hoa, A. X., & Techato, K.

(2022). Determination of optimal renewable energy

growth strategies using SWOT analysis, hybrid MCDM

methods, and game theory: A case study. International

Journal of Energy Research, 46(5), 6766-6789.

Apollo, M., & Andreychouk, V. (2022). Mountaineering

adventure tourism and local communities: Social,

environmental and economics interactions. Edward

Elgar Publishing.

Barbera, F., Cersosimo, D., De Rossi, A., & l'Italia, A. R.

(2022). Contro i borghi: Il Belpaese che dimentica i

paesi. Donzelli Editore.

Biconne, V. (2020). Borghi italiani come destinazione

emergente: identificazione dei cluster e diffusione di

Airbnb= Italian villages as emerging travel

destinations: cluster analysis and Airbnb diffusion

(Doctoral dissertation, Politecnico di Torino).

Bisu, A. A., Ahmed, T. G., Ahmad, U. S., & Maiwada, A.

D. (2024). A SWOT Analysis approach for the

development of Photovoltaic (PV) energy in Northern

Nigeria. Cleaner Energy Systems, 100128.

Bitušíková, A. (2021). Cultural heritage as a means of

heritage tourism development. Muzeológia a kultúrne

dedičstvo, 9(1), 81-95.

Bizzarri, C., & Micera, R. (2021). The Valorization of

Italian “Borghi” as a Tool for the Tourism Development

of Rural Areas. Sustainability, 13(12), 6643.

Božić, N., Dumbović Bilušić, B., & Kranjčević, J. (2019).

Urban transformation and sustainable development of

small historic towns. Cultural Urban Heritage:

Development, Learning and Landscape Strategies, 113-

125.

Capello, R. (2019). Interpreting and understanding

territorial identity. Regional science policy & Practice,

11(1), 141-159.

Capocchi, A., Vallone, C., Pierotti, M., & Amaduzzi, A.

(2019). Overtourism: A literature review to assess

implications and future perspectives. Sustainability,

11(12), 3303.

Castellano, R., Chelli, F. M., Ciommi, M., Musella, G.,

Punzo, G., & Salvati, L. (2020). Trahit sua quemque

voluptas. The multidimensional satisfaction of foreign

tourists visiting Italy. Socio-Economic Planning

Sciences, 70, 100722.

Choe, J. Y. J., & Kim, S. S. (2018). Effects of tourists’ local

food consumption value on attitude, food destination

image, and behavioral intention. International journal

of hospitality management, 71, 1-10.

Dawadi, S., Shrestha, S., & Giri, R. A. (2021). Mixed-

methods research: A discussion on its types, challenges,

and criticisms. Journal of Practical Studies in

Education

, 2(2), 25-36.

Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (2019). The phenomena of

overtourism: A review. International Journal of

Tourism Cities, 5(4), 519-528.

Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (Eds.). (2019). Overtourism: Issues,

realities and solutions (Vol. 1). Walter de Gruyter

GmbH & Co KG.

Ehrlich, D., Melchiorri, M., & Capitani, C. (2021).

Population trends and urbanisation in mountain ranges

of the world. Land, 10(3), 255.

European Commission. (2023). Glossary: Nomenclature of

territorial units for statistics (NUTS). Eurostat Statistics

Explained. Accessed on 17 November 2024, Available

at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-

explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Nomenclature_of_

territorial_units_for_statistics_(NUTS)

European Commission. (2024). Tourism policy overview.

European Commission. Accessed on 17 November

2024, Available at: https://single-market-

economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/tourism/policy-

overview_en

European Commission. (2024a). Consequences of climate

change. Climate.ec.europa.eu. Accessed on November

16, 2024, Available at:

https://climate.ec.europa.eu/climate-

change/consequences-climate-change_en

European Commission. (2024b). Coastal tourism. EU Blue

Economy Observatory. Accessed on 17 November

2024, Available at: https://blue-economy-

observatory.ec.europa.eu/eu-blue-economy-

sectors/coastal-tourism_en

Eurostat (2024). Urban-rural Europe - demographic

developments in rural regions and areas. ISSN 2443-

8219. Accessed on 17 November 2024, Available at:

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-

explained/index.php?title=Urban-rural_Europe_-

_demographic_developments_in_rural_regions_and_a

reas&oldid=651687

Garau, C. (2015). Perspectives on cultural and sustainable

rural tourism in a smart region: The case study of

Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability, 7(6), 6412-

6434.

Garau, C., Desogus, G., & Coni, M. (2019). Fostering and

planning a smart governance strategy for evaluating the

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

222

urban polarities of the Sardinian Island (Italy).

Sustainability, 11(18), 4962.

Gonda, T., Angler, K., & Csóka, L. (2021). The role of local

products in tourism. European countryside, 13(1), 91-

107.

Gretzel, U. (2021). Technological Solutions to

Overtourism: Potential and Limits. Mediterranean

Protected Areas in the Era of Overtourism: Challenges

and Solutions, 337-349.

Hamid, R. A., Albahri, A. S., Alwan, J. K., Al-Qaysi, Z. T.,

Albahri, O. S., Zaidan, A. A., ... & Zaidan, B. B. (2021).

How smart is e-tourism? A systematic review of smart

tourism recommendation system applying data

management. Computer Science Review, 39, 100337.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) (2021), Report

Migrazioni 2021, Accessed on 15 November 2024,

Available at:

https://www.istat.it/it/files/2023/02/REPORT_MIGRA

ZIONI_2021.pdf

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT) (2023). Annuario

statistico italiano 2023. Accessed on: 15 November

2023, Available at: https://www.istat.it/produzione-

editoriale/annuario-statistico-italiano-2023/

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). (2024), Accessed

on 11 November 2024, Available at: http://dati.istat.it/#

Kalyan, C. V., Rajeswari, V. N. A. S., Phaneendra, Y. S. D.,

& Kishan, S. R. (2024, April). Lokart: Empowering

Local Artisans through Mobile E-commerce. In 2024

International Conference on Emerging Technologies in

Computer Science for Interdisciplinary Applications

(ICETCS) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Lepore, A. (2020). L’evoluzione del divario tra il Nord e il

Sud dal dopoguerra a oggi. Estudios Históricos, 12(23),

2-63.

Les Plus Belle Villages de la terre (2024), Accessed on: 16

November 2024, Available at: https://lpbvt.org/

Major, D., & Juhola, S. (2021). Climate change adaptation

in coastal cities: a guidebook for citizens, public

officials and planners (p. 202). Helsinki University

Press.

Ministero del Turismo. (2024). Andamento turistico

italiano 2023. Ministero del Turismo. Accessed on 11

November 2024, Available at:

https://www.ministeroturismo.gov.it/wp-

content/uploads/2024/06/Andamento-turistico-

italiano-2023.pdf

Mokhov, I. I. (2022). Climate change: Causes, risks,

consequences, and problems of adaptation and

regulation. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences,

92(1), 1-11.

Ndhlovu, E., & Dube, K. (2024). Agritourism and

sustainability: A global bibliometric analysis of the

state of research and dominant issues. Journal of

Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 46, 100746.

OECD (2010). OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2010.

OECD Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264116030-it

Ounanian, K., Van Tatenhove, J. P., Hansen, C. J., Delaney,

A. E., Bohnstedt, H., Azzopardi, E., ... & Frangoudes,

K. (2021). Conceptualizing coastal and maritime

cultural heritage through communities of meaning and

participation. Ocean & Coastal Management, 212,

105806.

Pan, S. Y., Gao, M., Kim, H., Shah, K. J., Pei, S. L., &

Chiang, P. C. (2018). Advances and challenges in

sustainable tourism toward a green economy. Science

of the total environment, 635, 452-469.

Rey, R. (2015). New challenges and opportunities for

mountain agri-food economy in Southeastern Europe.

A scenario for efficient and sustainable use of mountain

product, based on the family farm, in an innovative,

adapted cooperative associative system–horizon 2040.

Procedia Economics and Finance, 22, 723-732.

Roman, M., Roman, M., & Niedziółka, A. (2020). Spatial

diversity of tourism in the countries of the European

Union. Sustainability, 12(7), 2713.

Romeo, R., Grita, F., Parisi, F., & Russo, L. (2020).

Vulnerability of mountain peoples to food insecurity:

updated data and analysis of drivers. Food &

Agriculture Org.

Skowronek, E., Tucki, A., Huijbens, E., & Jóźwik, M.

(2018). What is the tourist landscape? Aspects and

features of the concept. Acta Geographica Slovenica,

58(2), 73-85.

Statista (2024). Travel and tourism in Europe. Statista.

Accessed on 17 November 2024, Available at

https://www.Statista.com/topics/3848/travel-and-

tourism-in-europe/#topicOverview

Statista. (2023). Travel and tourism: Share of global GDP

2019-2034. Accessed on: 17 November 2024,

Available at:

https://www.Statista.com/statistics/1099933/travel-

and-tourism-share-of-

gdp/#:~:text=Travel%20and%20tourism%3A%20shar

e%20of%20global%20GDP%202019%2D2034&text=

Overall%2C%20these%20industries%20represented%

209.1,nearly%2010%20trillion%20U.S.%20dollars

Steiger, R., Knowles, N., Pöll, K., & Rutty, M. (2024).

Impacts of climate change on mountain tourism: A

review. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(9), 1984-

2017.

Streimikiene, D., Svagzdiene, B., Jasinskas, E., &

Simanavicius, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism

development and competitiveness: The systematic

literature review. Sustainable development, 29(1), 259-

271.

Sunder, S., & Dixit, S. (2023). Post-Pandemic Tourism: An

Article on the Recovery Strategies. Integrated Journal

for Research in Arts and Humanities, 3(2), 174-179.

Witara, K., Andriana, R., & Nugroho, D. C. (2024). A

Innovative Approaches: SWOT Analysis of Balinese

Souvenir Marketing in Sukawati Market During and

After the Pandemi. Warmadewa Management and

Business Journal (WMBJ), 6(2), 70-80.

Wyss, R., Luthe, T., Pedoth, L., Schneiderbauer, S., Adler,

C., Apple, M., ... & Thaler, T. (2022). Mountain

resilience: a systematic literature review and paths to

the future. Mountain Research and Development, 42(2),

A23-A36.

Analysing Italian Historical Small Towns: A Cultural and Geographic Mosaic of Identity

223