A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to

Language Courses at the University Level

Mathieu Loiseau

2 a

,

´

Emilie Magnat

3 b

, S

´

ebastien Dubreil

4 c

, Enzo Simonnet

1,2 d

and

´

Elise Lavou

´

e

1,2 e

1

Universit

´

e Jean Moulin Lyon 3, IAE Lyon School of Management, Lyon, France

2

Univ Lyon, INSA Lyon, CNRS, UCBL, LIRIS, UMR5205, F-69621, Villeurbanne, France

3

Universit

´

e Lyon 2, Laboratoire ICAR UMR 5191, France

4

Carnegie Mellon University, Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Vocabulary Learning Tool, Collaboration, Teaching Practices, Hybrid Learning.

Abstract:

While essential to second language learning, vocabulary learning is a complex and time-consuming task. It

rarely takes place explicitly in classrooms and, consequently, learners are often expected to carry out this

activity autonomously. Many tools targeting vocabulary learning exist, but they are frequently conceptualized

as stand alone products, leaving little room for integration within institutional curricula and collaboration

between learners. In this paper, we present a shared vocabulary notebook tool to enhance vocabulary learning

in and outside the classroom. This tool was designed according to an iterative and participatory process to

integrate both learners’ and teachers’ needs. In 2024, we conducted a 6-week study in 4 classes of French

L2 learners at Carnegie Mellon University. We explored both learners’ and teachers’ uses and perceptions

of the tool. We cross-checked interaction traces to qualitative outputs (i.e., focus groups carried out with the

learners and interviews involving participating teachers). We present results regarding the integration of the

tool in teaching and learning practices, the expectations and apprehensions linked to the collaborative and

social dimensions, and the limitations of a stand-alone vocabulary notebook tool. Our findings have broader

implications for the community as regards the design of tools to support vocabulary learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

Vocabulary learning is an essential dimension of for-

eign language learning (Jiang and Liu, 2024; Nation,

1999). While some go as far as arguing that devel-

oping enough vocabulary is “pre-conditional for suc-

cessful language learning” (Agust

´

ın Llach and Canga

Alonso, 2020, p. 2) others call vocabulary a “good

predictor” of global communicative skills of the stu-

dents (Lindqvist and Ramn

¨

as, 2017, p. 57). However,

the communicative approach had all but put lexicon

learning out of the scope of good language teach-

ing practices (Hilton, 2002, § 39). With the advent

of Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) and of the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9908-0770

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8857-9405

c

https://orcid.org/

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9740-5212

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2659-6231

Common European Framework, explicit work target-

ing the lexicon is no longer frowned upon (see (Coun-

cil of Europe, 2000, § 6.4.7.1.)).

Still, TBLT hardly gives insight on how to handle vo-

cabulary, it is “assumed that second language (L2)

vocabulary [will] take care of itself” (Schmitt and

Schmitt, 2020, p. 32). In this context, vocabulary

learning, and its methodology, is often carried out

without the supervision of the teacher: as Lindqvist

and Ramn

¨

as explain it (for the case of Sweden)

though vocabulary is not taught, it cannot be said

that it is not learnt (Lindqvist and Ramn

¨

as, 2017,

p. 59). Indeed, the mastery of the necessary few

thousands words

1

has to be acquired in a large part

autonomously, outside the classroom. Indeed, many

studies highlight the need to encourage independent

and autonomous learning (Ginanjar Anjaniputra and

1

Some 3000 families of words, at least, are required to

communicate in a foreign language (Laufer, 1992).

Loiseau, M., Magnat, É., Dubreil, S., Simonnet, E. and Lavoué, É.

A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to Language Courses at the University Level.

DOI: 10.5220/0013428700003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 555-564

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

555

Salsabila, 2018; Farangi et al., 2015).

Numerous Technology-Assisted Vocabulary

Learning (TAVL) tools

2

have been developed and

have shown positive impact on learning processes,

particularly concerning new vocabulary (Hao et al.,

2021). However, these tools have shown certain limi-

tations when used autonomously by learners. Based

on a review study on TAVL, Klimova suggested such

applications should be used in a guided and controlled

context to lead to a more effective learning process

(Klimova, 2021). Therefore, involving the teacher

in the learning process appears as a key element

to ensure that students learn vocabulary efficiently

outside the classroom. Yet, the question of how to

best harness TAVL resources in language learning

“is still in its youth, but is likely to become a major

focus of research in the coming decades” (Schmitt

and Schmitt, 2020, p. 25).

In this context, the Lex:gaMe project aims to de-

velop a personalized digital vocabulary learning en-

vironment that provides affordances for vocabulary

learning both inside the classroom and outside the

classroom. One of its main objectives is to make the

link between the two learning situations explicit and

provide both learners and teachers control over the

content. The first building block of this learning envi-

ronment, called BaLex, is a shared vocabulary note-

book that was created according to an iterative and

participatory design process.

Despite its design process involving both teach-

ers and learners, a first study highlighted Schmitt’s re-

marks: teachers did not integrate BaLex in their prac-

tices (Driediger, 2024) and learners even less so.

In this paper, we take a step back and follow more

closely the way BaLex can be integrated into a daily

language teaching and learning practices, both on the

teacher and learner’s side. We present a case study

carried out with 6 groups of French students at the

Department of Languages, Cultures and applied Lin-

guistics at Carnegie Mellon University (USA). Be-

yond feedback on our own tool, this study means to

provide insight as to the factors of successful integra-

tion of TAVL tools in classrooms.

To ground this study, we first provide a theoret-

ical background on vocabulary learning and identify

the specific challenges that arise. We review exist-

ing TAVL tools to identify relevant functionalities, as

well as limitations. We then present BaLex, before

2

Although the acronym TAVL is not widely used, we

believe it makes a logical addition to Mobile-Assisted Vo-

cabulary Learning (MAVL) (Ye et al., 2023; Ma, 2017) and

Computer-Assisted Vocabulary Learning (CAVL) (A. Al-

Jasir, 2019). It is noteworthy that the expression

“Technology-Assisted Vocabulary Learning” has already

been used in (Hao et al., 2021).

focusing on the case study: we analyse both quanti-

tative and qualitative data on learners’ and teachers’

uses and perceptions of BaLex, and draw recommen-

dations regarding the design and integration of tools

to support vocabulary learning.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Vocabulary Learning

“Vocabulary” refers to the set of words known by an

individual (in reception or production); it represents

a subset of the lexicon. The term “lexicon” refers

to all the lexical units of a language. This goes be-

yond the mere notion of “word”. In fact, the lex-

icon is made up of different types of “lexical enti-

ties” (Polgu

`

ere, 2019). Though vocabulary learning

has often been linked to making associations between

a word form in L2 and a first language (L1) coun-

terpart (Oxford and Crookall, 1990), this is a more

complex process. Indeed, knowing a word involves

many aspects of the lexicon that could be grouped into

three categories (Tremblay and Anctil, 2020, fig. 1):

form, meaning, and use (Nation, 2013, p. 49). Each

category encompasses both productive and receptive

knowledge. Form designates the oral and written

forms (spelling, sinograms) of the word but also its

morphology. Meaning deals with associating a con-

cept to a word form or finding a word form to desig-

nate a concept but also addresses polysemy and asso-

ciations to the concept/word form. Finally, “use” (or

“combining” for Tremblay and Anctil) covers gram-

matical functions, collocations and constraints on use

(register, frequency, style, connotations, etc.). The

notion of lexical competence, also encompasses the

attitudes towards vocabulary learning (Tremblay and

Anctil, 2020). This dimension known as “word con-

sciousness” is defined as “interest and awareness in

words” (Scott and Nagy, 2009, p. 127) and, as such,

also comprises a form of knowledge.

Since one type of activity cannot address all as-

pects of vocabulary learning, a wide range of learning

activities can be found in literature. The importance

of teachers considering individual learning styles is

emphasized by Oxford and Crookall (1990), particu-

larly in the context of vocabulary learning. For them,

teachers should acquaint themselves with diverse vo-

cabulary instruction tools and integrate training on

these tools into regular classroom activities. Teng

concurs and argues that teachers need to help students

develop the depth and size of their vocabulary knowl-

edge by devoting time to teaching some vocabulary-

learning strategies (Teng, 2014).

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

556

2.2 Technology-Assisted Vocabulary

Learning

Many TAVL tools have been developed over the past

two decades to support vocabulary learning. In a

2022 meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of

such technology, 34 studies with 2,511 participants

yielding 49 separate effect sizes were analyzed. The

meta-analysis identified a moderate overall positive

effect size for using technology to learn L2 vocabu-

lary (Yu and Trainin, 2022). With a similar scope, a

meta-analysis of 45 studies conducted between 2012

and 2018 on TAVL for English as a Foreign Language

(EFL) learners found an overall large positive effect of

TAVL, compared to traditional instructional methods

(Hao et al., 2021). Specifically, MAVL has consistent

results with the previous analyses: in 33 studies car-

ried out between 2005 and 2018, an overall positive

and large size effect on L2 word retention has been

found (Lin and Lin, 2019).

Beyond the tools themselves, a way to enhance

learners’ acquisition in vocabulary-centered tasks is

to offer collaboration opportunities (Laal and Laal,

2012). Collaborative tasks are in line with the princi-

ples of TBLT and might foster “word consciousness.”

In a meta-analysis we conducted, however, only 17%

of the TAVL tools incorporated collaborative features

(Simonnet et al., 2025).

Finally, we observed that few tools specifically ei-

ther include the teacher in the learning process or en-

sure that students learn vocabulary efficiently outside

the classroom. Indeed, only 26% of the tools inte-

grated teachers functionalities (and less than half of

these tools allowed the teachers to specify the con-

tent) (Simonnet et al., 2025).

3 BALEX

To address the aforementioned limitations of existing

tools for supporting vocabulary acquisition, we pro-

pose BaLex, a collaborative vocabulary notebook de-

signed to 1) bridge in-class activity and out-of-class

autonomous learning by relying on user-generated

lexical input, and 2) facilitate collaboration between

students through dedicated functionalities. The first

objective highlights the need for teacher involvement.

The second means to encourage learners to take an ac-

tive part in vocabulary learning while seeing the task

as a “team sport”, receiving the necessary support and

guidance from their teachers. Teachers, indeed, are

given the functionalities to play a central role in guid-

ing learners, monitoring progress, providing feedback

and giving instructions on the ways of using the tool.

To explicit how we tackled these objectives in our

design of BaLex, we describe its main features in this

section.

3.1 Lexicons

BaLex organizes lexical knowledge in vocabulary

notebooks (Nation, 2013, p. 140), we refer to as “lex-

icons”. By default, learners have access to an individ-

ual (and private) lexicon. Users can subsequently cre-

ate or join groups, each group manages its own shared

lexicon.

Each lexicon is associated has a home page with

the same features (see Fig. 1). It allows teachers and

learners to sort, organize and manipulate large lexi-

cons, displayed as lists of words. Users can sort the

entries (by alphabetical, addition date, or random or-

der). For each entry, users can toggle a quick view

of the word’s definitions. They can also select entries

and perform actions on the selection: export the se-

lection of words into a different lexicon, delete them,

mark them as known ( ) or not yet known ( ), and

apply labels and deadlines.

Labels enable users to list entries according to var-

ious criteria, in the form of tags attached to a word

and providing information about it (e.g. the labels

Animal, Travel, Feeling, etc.). Labels thus serve

both organizational and learning purpose. By cre-

ating their own labels and applying them to words,

learners might gain knowledge about the meanings of

the words they are labeling. Moreover, they can get

an understanding of the concept of polysemy. Labels

consist of several parameters: a name, a type (general

or milestone), a category of users that can access it

(personal, group or public).

The general labels are added by users, they can

have a “universal” scope (e.g., Sport, Animal), a

scope specific to the label’s creator (e.g., Words that

sound good) or a scope specific to a group (e.g.,

Words we laughed about). The deadlines operate

similarly to general labels, but they also require

a date specified by the creator (e.g. {Next class,

05/01/2025}, {Final exam, 20/03/2025}). When the

date is reached, a dialogue box asks the label’s cre-

ator whether they want to delete or renew it (in which

case, a new date is requested).

The owner parameter determines which users have

the right to modify the label. There are 3 different

modes:

• Personal Labels correspond to a unique user who

has exclusive access to it (rights to view, modify,

use, delete).

• Group Labels are accessible by a unique group

and only group members can access them. This

A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to Language Courses at the University Level

557

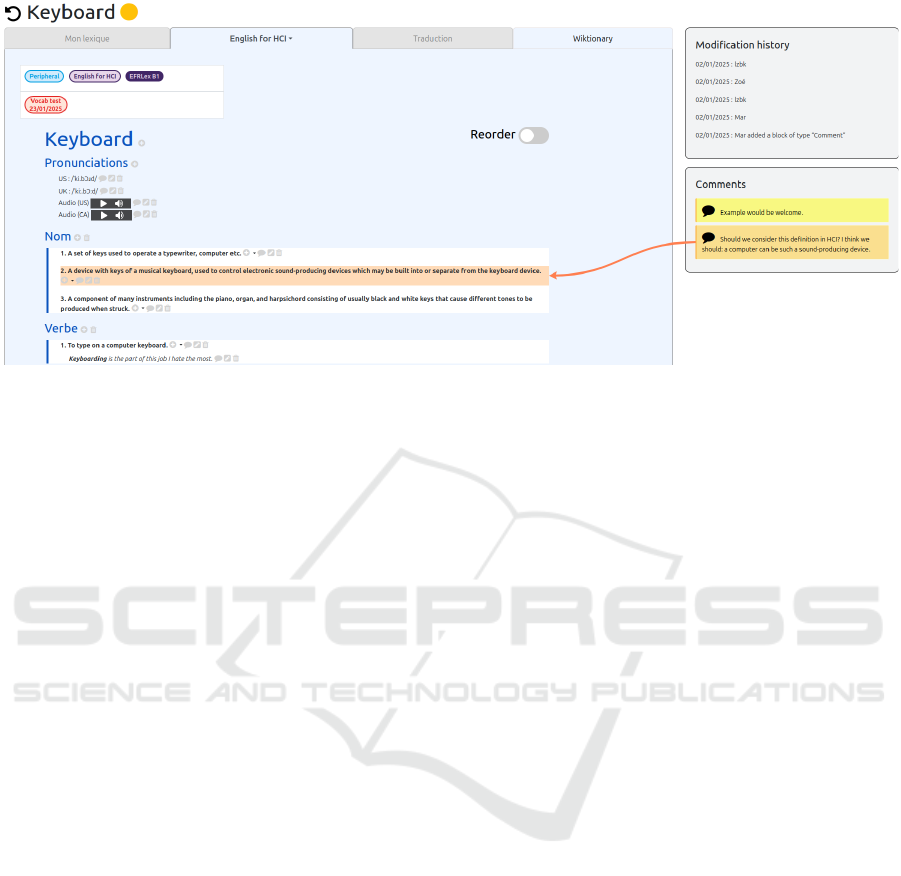

Figure 1: An example of shared lexicon. At the top, the bar allows users to search for a word in their lexicon. If not found,

BaLex will look for it in the Wiktionary. Words can be sorted. Toggle buttons display definitions without having to change

pages. The button at top right allows users to add word lists directly.

type of labels can allow teachers to mark some

words with useful information for the students,

such as with a label “For the project” or “False

cognates.”

• Public Labels are available to all BaLex users and

everyone has access to them. For critical actions,

such as deleting or renaming the label, an “ap-

proval” vote is initiated before making the change.

Every BaLex user can participate and vote “In fa-

vor” or “Against” the action.

On the lexicon main page, users can look up words

in the search bar. It will check whether the word al-

ready is in the lexicon, if not it will propose to add

it. They can also add a whole list of words, which

may be more convenient for teachers, by copying

and pasting a list in BaLex or typing an entire list

before asking BaLex to look them up. For every

word in the list, the software looks for the word in

the Wiktionary and imports/creates the correspond-

ing entry. The lexical information is extracted from

the Wiktionary and a copy is stored in the applica-

tion database using Python scripts that automatically

retrieve and structure it. Each language has its own

Wiktionary with its own structure and templates (we

currently process the French and English Wiktionar-

ies). Users can then consult the entry and modify all

the information: add, remove and reorder pronunci-

ations, parts of speeches, definitions, examples, sub-

definitions and sub-examples.

3.2 Collaborative Features

BaLex defines three distinct levels for organizing lex-

ical data. The primary lexical database encompasses

reliable information extracted from the Wiktionary in

the corresponding language. At the group level, col-

lections are dynamically managed by a student group

(such as class lexicons or work group lexicons), with

or without a supervising teacher. Additionally, users

have their own personal lexicon.

Anyone can create a group and invite new mem-

bers into the group (and its associated lexicon). The

creator of the group is initially the sole administrator

of the group. In order to simplify rights management,

3 roles have been designed (higher roles also encom-

pass the rights of lower roles):

• Administrator: change the role of other members

(including administrator). Open the lexicon for

modification by all members for a specified period

(e.g., 2 hours or 2 weeks)

3

.

• Contributors: invite members, modify the lexi-

con, and comment on entries.

• Readers: consult entries, sort lexicon, select and

export entries.

The collaborative lexicons each contain a discus-

sion zone enabling members to interact, either hor-

izontally between learners to share tips, discuss the

work to be done or discuss casually, or vertically from

teachers to learners to share instructions, advice and

feedback (cf. fig. 1). Comments can be added to any

lexical information on the entry page to encourage

discussion between learners in a same group or to give

feedback and indications (cf. fig. 2).

3

For instance, teachers can use it for a classroom work

session or homework.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

558

Figure 2: An example of entry. Top left, the icon returns to the lexicon. Learners can click on the orange dot to turn it green

(if they know the word). Labels are displayed above pronunciations, then parts of speech with their definitions and examples.

Each element can be modified, commented, deleted or added.

3.3 A Scenario

As a conclusion to this section, we tried to chose

screenshots that would elicit a potential scenario for

BaLex use. In this case, students are participating to

a specific class targeting the use of English for Hu-

man Computer Interaction. All students participat-

ing to the class are given access to a shared lexicon.

The teacher decided to pre-load a set of entries using

the ”add a word list” button (cf. § 3.1). The teacher

also indicated that a test was coming and labeled the

words to learn for that situation (cf. fig.1). To pre-

pare learners for their work, the teacher gave a few

tasks in class: remove vernacular senses for entries

such as mouse. “M” takes over the task (chatroom

fig. 1) and did it as can be seen in the quick view of

the definitions. To perform the task, they had to un-

derstand each definition before deciding that it was

linked to HCI or not and thus was made aware of the

many senses associated to the same entry.

After the next class the teacher gives a new task

which is to add labels to entries depending whether

they describe peripherals or design practices. To per-

form the task learners need to understand the concept

behind each word. While doing so, “Mar” realizes

that the musical keyboard might also be relevant for

HCI and adds a comment in the entry page (fig. 2).

While doing so she realizes she has a good under-

standing of the concept and turns the yellow circle to

green.

This scenario is by no means exhaustive — even

without considering the eventual catacreses (B

´

eguin

and Rabardel, 2000) that will come with the intensive

use of any technological artifact —, but gives

an oversight of the main functionalities.

4 STUDY ON THE USES AND PER-

CEPTIONS OF BALEX

To analyze how users, both teachers and learners, per-

ceive the introduction of BaLex, we conducted an

ecological study at Carnegie Mellon University in

early 2024 over a period of 6 weeks. We explored

the uses and perceptions of BaLex, both by learners

and teachers, in the context of their French classes.

We first describe the design before reporting detailed

results in next section.

4.1 Design and Participants

This study was a quasi-experimental design mixing

quantitative and qualitative data collection. This de-

sign was selected to observe uses and collect qual-

itative data on a low number of students. Partici-

pants were adult university students at Carnegie Mel-

lon University attending French classes. They were

recruited in the classes of the teachers that had pre-

viously agreed to take part in the experiment. The

experiment involved four teachers and six different

classes:

1. T

1

had one face-to-face class of 8 advanced

level students and one face-to-face class of 8

intermediate-level students;

2. T

2

had one face-to-face class of 13 beginner level

students;

A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to Language Courses at the University Level

559

3. T

3

had two online classes of beginner level stu-

dents, the first class had 47 registered students

and approximately 20 recurrent participants in

the weekly video-conference class, the second

class had 27 registered students and approxi-

mately 12 recurrent participants in the weekly

video-conference class;

4. T

4

had one face-to-face class of 7 intermediate-

level students.

The subjects are overwhelmingly female (> 70%).

Face-to-face classes had a mean age of 20 years old

whereas the remote class had a mean age of 50 years

old. All participants are native English speakers with

the exception of 1 native Chinese speaker that had an

advanced proficiency level in English.

4.2 Instruments and Data Collection

We collected several types of data:

• User traces: Lexicon and entry views were

logged, as well as the addition of an entry to a lex-

icon or of a label to an entry. Each modification

to an entry was also the object of a log.

• Logbooks: Teachers were asked to fill an online

logbook after each class.

• Interviews: semi-directed interviews were con-

ducted with T

1

, T

2

and T

3

.

• Focus group: 6 students from T

1

’s Advanced level

class participated to a 30 minutes focus group.

4.3 Experimental Protocol

For each group, the experiment was launched during

the second class of the semester. We visited the class

and gave a 10-minute introduction to the BaLex envi-

ronment. Then, students were asked to fill the pretest

questionnaires. Based on the pretest

4

, accounts were

automatically created and a connection link was sent

to each student by e-mail. From then on, the students

were free to use the tool at will. We simply recom-

mended a frequent use, if possible a dozen minutes

per day. The research was carried out over the course

of 6 weeks.

Teachers were also provided with an account and

were recommended to include the use of BaLex in

their teaching practices. We co-designed with each

teacher a specific pedagogical scenario before the

start of the experiment.

4

E-mail addresses were collected at the end of the

pretest. The pretest survey analysis is not part of the scope

of this article.

Indeed, depending on the level of proficiency of

the students and on the practices of the teachers, dif-

ferent approaches were considered. Some teachers

(e.g. T

4

or T

2

) preferred adding entries themselves

and let the students work on the entries, while others

(such as T

1

) wanted their students to create the entries

themselves based on their needs in the preparation of

the final task.

Information about the experiment was available

on the Learning Management System (LMS) used for

the courses. It was clearly indicated that participation

to the experiment had no influence on their curriculum

in terms of penalties or bonuses during the semester.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Sample Description

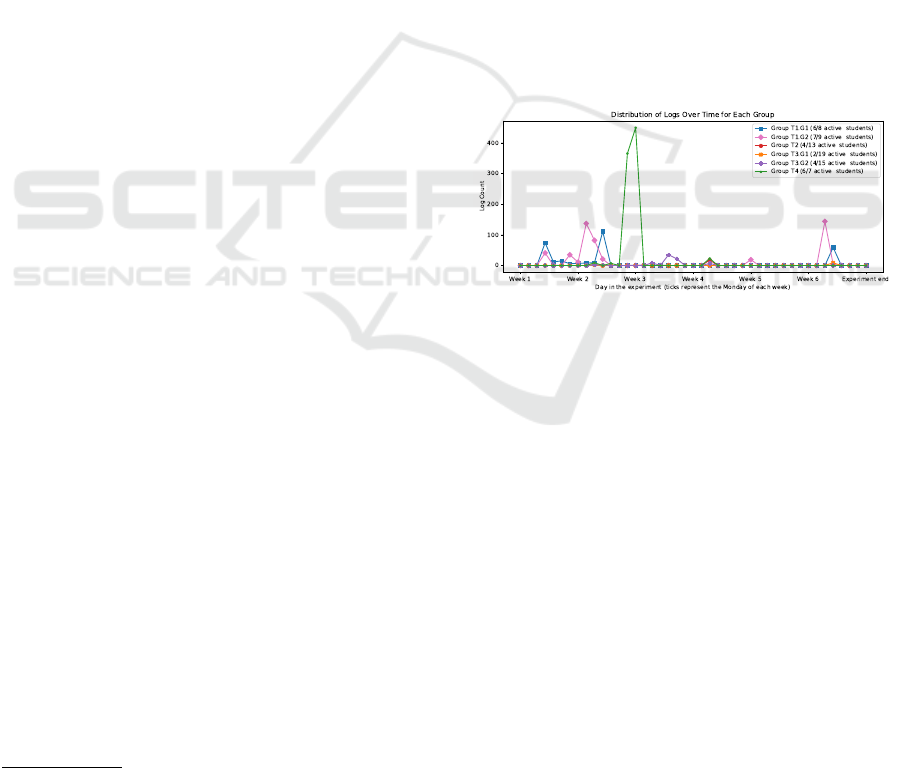

In fig. 3 we display the logs of the students’ engage-

ment with lexicon entries. Each “log” is an action of a

member of the group directed towards an entry (view,

edit, label action).

Figure 3: Distribution of logs over time for each groups.

To understand better fig. 3, we should provide in-

sight on the number of students engaging with the en-

tries. Despite working with small groups, no class

had all students engaging with the entries. In propor-

tion, distance students engaged less in the tasks than

the face-to-face students. This was expected: T

3

ex-

plained that distance students were mostly adults tak-

ing a language module, while face-to-face students in-

tegrate French classes in their degree. In T

3

’s group

1, most students did not even log in once. But that

was also the case in T

2

’s class.

In most groups, students engaged with the system

“in peaks” that directly followed or happened dur-

ing a class. The distribution of these peaks failed

to display regularity in the activity of the learners.

Furthermore, the students in the focus group admit-

ted spending a maximum of 30 minutes in total on

BaLex over the course of the experiment. In order

to better understand these activity peaks, we relied

on teacher data. We analyzed the 13 logbook entries

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

560

filled, mainly at the beginning of the experiment

5

,

with post-experiment interviews.

5.2 Integration into the Course

As mentioned in section 4.3, teachers did not integrate

BaLex using the same usage scenario. In this section,

we describe the regularities and differences between

groups.

5.2.1 Presentation of BaLex to the Students

The tool was only demonstrated once at the end of

one of the first classes (to show how to add words,

comments or change definitions)[T

3

-logbook]. At the

start of the course, the teachers told the students that

BaLex was a tool for them to work on vocabulary.

This was at a time when there were already “a lot

of things to put in place”[T

2

-logbook]

6

. It was mainly

during the first and second classes that the teachers

mentioned BaLex, they hardly ever did so during the

next classes[logbook]. The mentions of the tool are

mainly explanations of the experiment (visit by the

researcher, survey to be completed, encouragement

to use it) or response to student questions. Teach-

ers were regularly asked questions about BaLex’s use

by learners[interviews+logbook]. Learners would also have

liked a tutorial when they first logged on[interviews].

The fact that teachers were asked about the tool

could be interpreted as a link between the teachers’

supposed adoption of the tool and the learners’ intent

on using it. We elaborated on that assumption in sec-

tion 5.3.

5.2.2 Modalities

While T

3

displayed awareness of TAVL in the class-

room (mentioning the use of such tools as WordRefer-

ence, Linguee, Reverso and Duolinguo School), other

teachers did not mention such experience. T

3

is also

the only teacher who declared dedicating time to us-

ing BaLex in class. She showed how to add words or

comments, and how to modify definitions [Logbooks].

All teachers mentioned BaLex explicitly at one

point or another. Some mentions concerned the tool in

itself. T

3

reported discussing the tool in class because,

in her opinion, the students had not used it enough.

They therefore discussed how and why to use it.

All teachers but T

4

gave explicit out-of-class work

involving BaLex, i.e. in addition to the general in-

5

out of the 42 classes that took place during the experi-

ment

6

“All testimonies present in the analysis are identified

like this”[source]

struction to use the system for new words. But they

only did so once per group during the experiment

[logbooks]. T

3

asked “to define the words [. . . ] added

to BaLex after the lesson [or] to add words to our

class lexicon and their personal lexicons and that we

would discuss them next week”[Logbooks]. For his part,

T

1

asked learners to make the link between BaLex

and the Slam workshop they were attending (“As you

enter the Slam workshop, add the words you dis-

cover/search for to your BaLex lexicon”).

T

1

added entries but did few modifications to said

entries himself, mainly watching learners’ activity

through the history of modifications. He checked the

work done by the learners, mainly by looking at what

had been added. The majority of teachers indicated

that they had not added words to the lexicon them-

selves. On the contrary, T

2

added lists of predefined

words in preparation for the next lesson, and, T

2

and

T

3

both added words in preparation for the next les-

son and the words that had emerged during interac-

tions with their students. In most cases, the teachers

expected learners to add new vocabulary to the group

lexicon after each class.

However, in order to initiate the practice among

learners, it seems important for the teacher to set an

example.

5.3 Influence of the Teacher’s Action

In group T

3

G2 there were very few learner actions, if

any, outside of week 3 and 4, when there were many

logs (up to 35 per day). It was also during this period

that the teacher indicated in the logbook that she had

shown the class how to add words and had led a dis-

cussion on why to use the tool. During that period T

3

added 9 words that had emerged during the lesson to

the group lexicon. One learner added 5 words to the

group lexicon and 22 entries were added to personal

lexicons (4 of these entries came from the group lexi-

con).

In much the same way, analysis of the logs in T

1

’s

groups reveals a common period of high connection

(Weeks 1 & 2 and Week 6). The first peak (Week 1

and 2) corresponds to the presentation of BaLex in

class and the first week of work. Week 6 peak cor-

responds to his mention of the creative part of the

semester starting, and the slam workshop (see above).

The influence of the teacher’s action on the logs

can also be seen in T

4

’s class. During week 2, she

asked the students to clean up 15 entries each week

and add the “cleaned” label to those entries. That re-

sulted in the addition of roughly 600 entries. During

the class of week 3, she had “a discussion with the

students (for 20 minutes, too long!) because they had

A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to Language Courses at the University Level

561

questions about BaLex”[logbook]. Following that dis-

cussion, she reduced the instructions to adding 1 entry

per week per student. The learners in this group then

stopped using the tool altogether. It should be noted

here that the teacher said that she did not check what

the learners were doing on BaLex [logbook].

Learners underlined the importance of teachers in-

structions: “[we only used BaLex] because we were

told to”[focus group], while another said “I didn’t add

anything but I thought about adding.” The incentive

provided by teachers instruction should ensure that

the task is short enough not to discourage the learn-

ers. Teacher contribution might also be an incentive

for learners to engage in the vocabulary work.

5.4 Teachers’ Difficulties and Usefulness

to Students

It is important to point out, however, that the teacher

contributions might be hindered by technical difficul-

ties. Some teachers stated that they had difficulties

with the tool during the experiment. T

2

indicated,

for example, “not knowing how to add words (sin-

gular, without article), not being able to add word

lists”[logbook]. Her additions were mainly word lists

in preparation for the next lesson. With our help, she

ended up adding 336 entries to the group lexicon. For

his part, T

1

confided that he had difficulty “[adding]

things like proper names or things that are referring

to idiomatic expressions, not idiomatic expressions,

to grammar points because I wouldn’t know where to

start”[interview]. He did, however, mention an interest-

ing use that emerged from the needs of the class: “We

were looking for the etymology of a word and a stu-

dent added it to the group’s lexicon”[T

1

G2]. T

1

added

32 entries in the lexicon of T

1

G1 and 6 in T

1

G2’s.

T

1

, for his part, does not use any other tools for

teaching vocabulary and considers that using BaLex

makes this work more “enjoyable”, in particular be-

cause “it affords different possibilities both for the

teacher and the students” and because of the possi-

bility of sharing the lexicon within a group and being

able to put labels on it. He acknowledged that this was

his first time using the tool and said that he would use

it again in the future, but in a different way — without

explaining what he would change in his use.

According to T

3

, being able to personalize the lex-

icon was very interesting and being involved in the

study made learners aware of the importance of work-

ing on vocabulary. T

2

added that this study “helped

[her] in regard to just being even more aware of

what vocabulary the students were using it for each

unit”[interview] and that she appreciated being able to

filter words by label. She managed 350 entries and

underlined the relevance of that functionality. She

did not ask the students to create the entries because

“[her] class has the hybrid format and so they are al-

ready doing a lot on the OLI platform”[interview]. She

admitted that the creation of the word corpus will be

useful to her for years to come.

In T

3

’s view, the tool may not be accessible to all

learners. For weaker learners, “it was a little out of

their reach because the definitions are in French”,

even “frustrating.” She suggested that a translation

function would help. On the other hand, T

2

consid-

ers that the tool is appropriate for elementary learners

who can use it instead of a translator. The advanced

learners in the focus group, for their part, stated that

the tool was adapted to their level of French.

One of the main benefits of BaLex is that “when-

ever you put a word in it tells you all the different def-

initions even if they’re not related to the class”[focus

group]. This is common to most dictionaries, the pos-

sibility to clean up the entries is not: “When I’m

trying to figure out the right word or right defini-

tion it’s usually a passive thing but there I’m actively

putting something in which like helps me remember it

more”[focus group]. Learners participating to the focus

group concurred that they were more keen on using

BaLex on an occasional basis rather than on an on-

going basis. Exploring what they meant, one learner

stated “like after class I want to review like if there’s

any new words”[focus group]. This points towards regu-

lar use, but as a spectator, not an actor. This under-

lines the issue of the time allotted to the task (which

is inherent to vocabulary learning).

5.5 How Do Students Experience the

Cleaning of Entries?

One of the main features of the BaLex tool is the abil-

ity to retrieve entries from the Wiktionary and then

adapt its content to the user’s needs. Users can add,

delete or change the order of definitions or examples

in their lexicons (personal and group). The changes

cannot be undone in one click, but it is possible to

re-import from the wiktionary or another lexicon or

manually correct the change in the other direction. On

this point, feelings seem to be divided.

One learner noted that “removing the definitions

was helpful then it allowed you to go through all of

them and then that way you’re kind of more actively

engaging with the word”[focus group]. Conversely, an-

other learner admitted that it was really hard to re-

move definitions. He considered it was “losing that

definition because you’re not using it in that con-

text” and finally suggested that “there should have

been a way to like highlight certain definitions but

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

562

not delete them entirely maybe”. T

1

agreed with this

suggestion (“highlight some and shade others without

deleting”[interview]). Another suggested having “like

a check box of which you want to remove” because

removing them individually takes time. One sug-

gestion for improvement to avoid deletions would be

to put a label on the definitions rather than on the

words. Finally, T

2

felt that to take full advantage

of this feature, a minimum level of French was re-

quired (“I didn’t feel like I could assign the task you

talked about, where they’d get rid of definitions, be-

cause they wouldn’t know what they were getting rid

of ”[interview]).

Teachers and learners therefore recognized the

value of tidying up entries. However, their comments

reveal the apprehension of doing things wrong and the

limits of deletion, which cannot easily be undone.

5.6 The Collaborative Dimension: From

Perceived Interest to Practical

Implementation

The collaborative dimension was mentioned by T

1

:

“the best learning is always a team sport”[interview].

Only T

3

took advantage of this aspect. She presented

it as a competition between learners “competing with

each other and seeing who’s doing well in class there

or who’s winning or whatever”[interview], a competi-

tion that she encouraged by announcing the most in-

volved learners each week. As for the learners, when

the experimenter asked whether using BaLex made

learning vocabulary easier or more enjoyable, one

replied “I think it was useful to help us collaborate

and share each other’s words”[focus group]. Another

learner, when asked about his favorite features of

BaLex, replied “I like the collaborative aspect when

you can see everyone else’s words and then like to edit

theirs and then add you own”[focus group]. But learn-

ers also admitted that “nobody used the collab fea-

tures”[focus group] and that they did not add words of

the shared lexicon to their personal lexicon.

The lack of action on definitions and examples

could also be linked to the fact that learners tradition-

ally have lists of word-definitions ready to learn, with-

out acting on them or customizing them. Although

some learners produce or personalize their lists, they

do so on an individual basis. The collaborative ap-

proach used in BaLex to create a common lexicon re-

quires learners to take responsibility, and some may

not be comfortable with the idea of being responsi-

ble for the final collective result. This is also visible

in the little use students made of the labeling feature.

Indeed, all learners combined created 4 labels while

the other dozen of group and public labels were made

by teachers.

6 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we reported a case-study of a TAVL soft-

ware called BaLex, designed as a collaborative vocab-

ulary notebook. The need for this kind of tool is high-

lighted by the body of work around the importance

of vocabulary learning, which should not be focused

solely on size but also on depth. With that in mind,

we developed a first version of BaLex. In this paper,

we reported the results of a study that took place in

an ecological setting at the department of Languages,

Cultures and Applied Linguistics at Carnegie Mellon

University, which we believe suggest broader impli-

cations in the field for the design of TAVL tools.

The data particularly showed that teachers had

different ways of integrating BaLex in their courses.

These choices depended mainly on the students’ pro-

ficiency level, but also on the instructional context

(adult classes vs regular classes) and modality (face-

to-face, hybrid or distance learning).

In terms of integration of TAVL tools, we should

underline the importance of teacher activity. Traces

show that, for the most part, learner contributions

directly followed explicit instruction from teachers

(with other mild activity peaks after teacher partici-

pation to group lexicons).

Still, in the course of this experiment, the connec-

tion data showed that learners did not use BaLex as

much as expected. In addition to the feedback on the

functionalities detailed in previous sections, some of

the reasons given for low usage are directly linked to

the prototype’s aspect. The interface does not seem

to have appealed much to users. Our future work will

be dedicated to exploring how to integrate gamifica-

tion functionalities to improve learners’ engagement

with the learning environment. Indeed, learners seem

to be asking for a tool that goes beyond the lexical

base, a tool that allows vocabulary to be practiced in

fun activities. They want an application with more

colors, with a “scoreboard”[focus group] and that is less

“scholarly”[focus group]. With the idea of improving

vocabulary practice, learners go so far as to suggest

that “there’s tons of space to enter like little avatar

and progress bars to sort of remind you you’re work-

ing towards something not just words”[focus group] and

that “if you could make more addicting it would be

good”[focus group].

Those remarks are all the more encouraging in

that they are inline with the roadmap of the Lex:gaMe

project. Beyond, the improvement of certain func-

tionalities of BaLex (cf. § 5.5), the next step is to in-

A Collaborative Vocabulary Notebook as a Complementary Tool to Language Courses at the University Level

563

terface the platform with two games that target differ-

ent levels of vocabulary knowledge: MagicWord for

low level skills (form, meaning) and Prisms (mean-

ing, usage, strategy). In order to evaluate the effect

of the upcoming games in vocabulary learning it was

also important to assess BaLex as a standalone envi-

ronment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the teachers who agreed to try

BaLex, for the extra work-time for them and the extra

information for us.

The authors also thank the ASLAN LabEx of Uni-

versit

´

e de Lyon (ANR–10–LABX–0081) for its finan-

cial support as part of the french program “Investisse-

ments d’Avenir” managed by the Agence Nationale

de la Recherche (ANR).

REFERENCES

A. Al-Jasir, M. (2019). Computer Assisted Vocabulary

Learning: A Case Study on EFL Students at Al-Imam

Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. Arab World

English Journal, (249):1–63.

Agust

´

ın Llach, M. P. and Canga Alonso, A. (2020). Vocab-

ulary Strategy Training to Enhance Second Language

Acquisition in English as a Foreign Language. Cam-

bridge Scholars Publishing.

B

´

eguin, P. and Rabardel, P. (2000). Designing for

instrument-mediated activity. Scandinavian Journal

of Information Systems, 12(1):173–190.

Council of Europe (2000). Common European Framework

of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, As-

sessment. Council of Europe ; Cambridge University

Press, Strasbourg ; Cambridge, UK.

Driediger, M. (2024). Une analyse de l’int

´

egration d’un

outil tice en lansad :

´

Etude de cas de l’outil balex dans

les cours d’anglais. mathesis, Lyon.

Farangi, M., Nejadghanbar, H., Askary, F., and Ghor-

bani, A. (2015). The effects of podcasting on EFL

upper-intermediate learners’ speaking skills. CALL-

EJ, 16:1–18.

Ginanjar Anjaniputra, A. and Salsabila, V. (2018). The mer-

its of quizlet for vocabulary learning at tertiary level.

Indonesian EFL Journal, 4:1.

Hao, T., Wang, Z., and Ardasheva, Y. (2021). Technology-

Assisted Vocabulary Learning for EFL Learners: A

Meta-Analysis. Journal of Research on Educational

Effectiveness, 14(3):645–667.

Hilton, H. (2002). Mod

`

eles de l’acquisition lexicale en L2

: o

`

u en sommes-nous ? ASp, (35-36):201–217.

Jiang, N. and Liu, D. (2024). Lexicosemantic Development,

chapter 2, page 13–23. Routledge Handbooks in Sec-

ond Language Acquisition. Routledge, New York.

Klimova, B. (2021). Evaluating Impact of Mobile Applica-

tions on EFL University Learners’ Vocabulary Learn-

ing – A Review Study. Procedia Computer Science,

184:859–864.

Laal, M. and Laal, M. (2012). Collaborative learning: What

is it? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences,

31:491–495.

Laufer, B. (1992). How Much Lexis is Necessary for Read-

ing Comprehension? In Arnaud, P. J. L. and B

´

ejoint,

H., editors, Vocabulary and Applied Linguistics, pages

126–132. London.

Lin, J.-J. and Lin, H. (2019). Mobile-assisted ESL/EFL

vocabulary learning: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. Computer Assisted Language Learning,

32(8):878–919.

Lindqvist, C. and Ramn

¨

as, M. (2017). L’enseignement du

vocabulaire

`

a l’universit

´

e. (11-12):55–64.

Ma, Q. (2017). Technologies for Teaching and Learning L2

Vocabulary, chapter 4, page 45–61.

Nation, I. S. P. (1999). Teaching and learning vocabulary.

Boston, Mass, nachdr. edition.

Nation, P. (2013). Learning Vocabulary in Another Lan-

guage. Cambridge Applied Linguistics. 2 edition.

Oxford, R. and Crookall, D. (1990). Vocabulary Learn-

ing: A Critical Analysis of Techniques. TESL Canada

Journal, 7(2):09–30.

Polgu

`

ere, A. (2019). Lexicologie et s

´

emantique lexicale :

Notions fondamentales. Param

`

etres. Montr

´

eal.

Schmitt, N. and Schmitt, D. (2020). Vocabulary in language

teaching. Cambridge University Press, second edition

edition.

Scott, J. A. and Nagy, W. E. (2009). Developing Word Con-

sciousness, page 106–117. International Reading As-

sociation.

Simonnet, E., Loiseau, M., and Lavou

´

e,

´

E. (2025). A sys-

tematic literature review of technology-assisted vo-

cabulary learning. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 41(1):e13096. e13096 JCAL-24-125.R1.

Teng, F. (2014). Research Into Practice: Strategies for

Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. Beyond Words,

2:41–57.

Tremblay, O. and Anctil, D. (2020). Introduction. —

Recherches actuelles en didactique du lexique :

avanc

´

ees, r

´

eflexions, m

´

ethodes. Lidil. Revue de lin-

guistique et de didactique des langues, (62).

Ye, S. X., Shi, J., and Liao, L. (2023). An evaluative review

of mobile-assisted l2 vocabulary learning approaches

based on the situated learning theory. Journal of Cur-

riculum and Teaching.

Yu, A. and Trainin, G. (2022). A meta-analysis examining

technology-assisted L2 vocabulary learning. ReCALL,

34(2):235–252.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

564