Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using

ESG

Veda Ganesan

Edward S. Marcus High School, Flower Mound, U.S.A.

Keywords: ESG, Corporate Valuation, CSR, Valuation Methods, Risk Assessment, DCF, Cost of Equity and ESG, Cost

of Debt and ESG, WACC and ESG, Environmental Impact on Valuation, Pre and Post Seed Funding, Startup

Valuation and the Macroeconomy, Beta Adjustment, Sustainable Finance, Macroeconomic Impact of ESG.

Abstract: Overvalued startups with unsustainable business models remain a critical issue, driven by market irrationality

and overlooked risks. This study introduces an ESG-integrated Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model to

address these valuation inaccuracies. By incorporating Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics

into the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), the model effectively accounts for ESG-related risks

and opportunities. The analysis reveals that startups with higher ESG ratings experience reduced costs of

equity and debt, resulting in a lower WACC and more accurate valuations. This approach highlights the

benefits of integrating sustainable practices into business models, promoting long-term stability and investor

confidence. A comprehensive review of existing valuation methods identified key gaps, particularly in

accounting for qualitative ESG factors. Regression analysis of case studies demonstrated how ESG-adjusted

discount rates improve valuation precision without double-counting risks. Findings suggest an inverse

relationship between ESG ratings and capital costs, emphasizing the financial advantages of robust ESG

frameworks. This research underscores the need for investors and venture capitalists to incorporate ESG

considerations systematically, reducing the risk of market bubbles and fostering sustainable business practices.

Future studies should explore nonlinear modeling and behavioral finance to further enhance ESG-integrated

valuation frameworks.

1 INTRODUCTION

Startups today often face inflated valuations driven by

overoptimistic expectations of future profits,

neglecting underlying sustainability and ethical

risks—a trend reminiscent of the Dot-Com bubble.

Traditional valuation methods, such as the Berkus,

Scorecard, and Venture Capital approaches, focus

mainly on tangible and intangible assets, overlooking

long-term sustainability and societal impacts. This

oversight not only distorts a startup’s true value but

also jeopardizes economic fairness and market

stability, affecting stakeholders from employees to

early investors.

In response, this research proposes an enhanced

valuation model that integrates Environmental, Social,

and Governance (ESG) factors with critical

multiplism. By incorporating multiple perspectives,

this approach provides a more nuanced understanding

of startup value, promotes transparency, and

mitigates risks associated with speculative bubbles.

Ultimately, the study advocates for a balanced

methodology that aligns financial potential with

ethical considerations, paving the way for more

sustainable and resilient entrepreneurial growth.

2 PROBLEM

Traditional corporate finance theory values a

company based on the present value of expected

future cash flows, discounted at a cost of capital

reflecting its financing sources. However, a

comprehensive startup valuation should also consider

factors like business models, market dynamics, and

risks. Recently, ESG factors have gained importance

in corporate finance, with sustainable investing

growing globally. Current valuation models for

startups often overlook ESG, failing to capture its

impact on long-term value and risk. Key challenges

in integrating ESG into startup valuations include

adjusting the discount rate or projected cash flows in

a DCF model, with issues like double counting and

232

Ganesan, V.

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG.

DOI: 10.5220/0013428900003956

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2025), pages 232-242

ISBN: 978-989-758-748-1; ISSN: 2184-5891

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

difficulty quantifying ESG impacts. This study

addresses these challenges by developing an ESG-

incorporated DCF model and testing it with a startup

already valued without ESG factors. A key challenge

for startup investors lies in integrating ESG factors

into valuation models, given the limited financial

history and uncertain future of early-stage companies.

Although CAPM adjustments have been suggested

for more mature companies, two primary approaches

have emerged to integrate the ESG factors into startup

valuation:

1. Adjusting the discount rate in a discounted cash

flow (DCF) model: This method posits that

startups with poor ESG practices may be

perceived as riskier, warranting a higher discount

rate and resulting in a lower valuation. However,

this approach faces two significant challenges:

1.1 Determining the appropriate adjustment

magnitude

1.2 There is a risk of double-counting if the startup

ecosystem has already priced in these risks. One

of the critical challenges in incorporating ESG

factors into startup valuation is avoiding double

counting, particularly when adjusting the

discount rate. Many traditional risk components,

such as company size, market risk, and leverage,

already capture certain ESG-related risks

indirectly. For instance:

1.2.1 Company Size Premium: The size premium

in CAPM accounts for risks associated with

smaller firms, such as governance

challenges and financial instability. These

risks intersect with ESG governance factors,

as lower board independence and weaker

shareholder rights can amplify governance

risks already considered in company-size

premiums.

1.2.2 Industry-Specific Risk Premiums: Industries

with high regulatory and environmental

scrutiny (e.g., energy, manufacturing)

already have elevated discount rates due to

anticipated compliance costs and policy

risks, which could overlap with ESG-related

risks.

2. Adjusting projected future cash flows in a DCF

model: This approach necessitates estimating the

impact of ESG factors on a startup's future

revenue, costs, and growth trajectory. While this

method encourages investors to consider the

tangible effects of ESG issues on the business

model, quantifying these impacts remains

challenging for early-stage companies.

This study aims to address the challenges posed by

the DCF Model discount rate approach (as described

in 1.1. and 1.2 above), contributing to the

development of more robust and comprehensive

startup valuation methodologies that effectively

incorporate ESG considerations through the

application of critical multiplism. The new ESG-

incorporated DCF model will be tested with a startup

that has already been valued without an ESG factor to

show how the new valuation changes the trajectory.

3 METHODS OF STUDY

This study employs comprehensive literature review

as its primary research method to explore the

phenomenon of overvalued startups, the traditional

and emerging valuation methodologies, and the

integration of ESG principles into these frameworks.

The literature review involves analyzing a diverse

range of sources, including academic reports,

company financial reports, industry analyses, and

relevant databases such as PitchBook. The following

steps outline the research methodology:

1. Literature Review:

1.1 Academic Reports: Peer-reviewed journal

articles and books provide a theoretical

foundation for understanding traditional and

contemporary startup valuation methods. Key

sources include seminal works on corporate

finance, sustainable investing, and critical

multiplism.

1.2 Industry Reports: Reports from industry experts

and consultancy firms like Deloitte and CFA

Institute offer insights into current practices,

trends, and challenges in startup valuation and

ESG integration.

1.3 Company Financial Reports: Analysis of

financial statements and reports from startups

and established companies helps in

understanding real-world applications of

valuation methodologies and the impact of ESG

factors on financial performance.

2. Qualitative Analysis:

The study conducts a qualitative analysis of the

gathered literature to identify common themes,

gaps, and inconsistencies in the existing

valuation methods. Comparative analysis of

different valuation models (e.g., Berkus Method,

Scorecard Method, Venture Capital Method)

highlights their strengths and limitations in

incorporating ESG factors.

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG

233

3. To operationalize ESG adjustments without

double counting, our methodology follows a

structured process:

3.1 Selection of ESG Factors: ESG factors are

screened for their relevance and uniqueness in

contributing to the startup’s valuation. Only factors

with demonstrated financial impact, beyond existing

discount rate components, are considered.

3.2 Quantification of ESG Impact: ESG scores from

multiple rating agencies are normalized. Regression

models are employed to determine the incremental

impact of ESG on financial performance.

3.3 Integration into Valuation Model: Discount rate

modifications (if necessary) are subject to statistical

validation to ensure they capture new information

rather than overlapping with existing risk factors.

By implementing these safeguards, our ESG-

integrated valuation model ensures a more accurate

reflection of startup value while systematically

preventing double counting.

4 LITERATURE REVIEW

Business valuation is inherently complex for any

company. When it comes to startups with minimal or

no revenue, uncertain prospects, and a lack of

established financial performance, determining a

valuation becomes particularly challenging. For

mature, publicly traded companies with consistent

revenue and earnings, the valuation process is

generally straightforward, typically involving

multiples of earnings before interest, taxes,

depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) or other

industry-specific ratios such as PEG, P/E, or P/B

ratios. However, evaluating a new, privately held

venture that might not yet be generating sales is

significantly more difficult. The challenge primarily

arises from:

1. Absence of Historical Financial Data

2. Uncertain Future Performance

3. Lack of Comparables

4. Dependence on Multiple Funding Rounds

5. Subjectivity and Bias

4.1 Startup Valuation Methods

Valuation methods for startups vary depending on the

stage of the startup, ranging from the early pre-

revenue phase to later stages with revenue and

established operations.

Figure 1: Valuation Framework along Corporate Lifecycle.

The following sections outline several of the most

commonly used valuation techniques.

4.1.1 Berkus Method

The Berkus Method, developed in the early 1990s by

Dave Berkus, is tailored for pre-revenue startups. It

assigns monetary values to key qualitative factors—

such as the soundness of the business idea, the

strength of the management team, product

development, market potential, and strategic

relationships—each capped at a predetermined limit.

This structured approach helps prevent overly

optimistic valuations in the absence of hard financial

data. However, its reliance on subjective assessments

and fixed value limits may oversimplify the complex

risk and opportunity profiles inherent in early-stage

ventures.

4.1.2 Risk Factor Summation Model

The Risk Factor Summation Model (RFSM) builds on

a baseline valuation by systematically adjusting for

various risk factors associated with startups. This

model quantifies risks—including management,

market competition, technological uncertainty, and

regulatory issues—by assigning numerical values to

each and then summing these adjustments. While

RFSM offers a more comprehensive risk assessment

than methods that rely solely on financial metrics, its

heavy reliance on subjective scoring and the

challenge of accurately weighing different risk

factors can result in inconsistent valuations. Ratings

for each risk factor can be evaluated as follows.

4.1.3 the Venture Capital Method

The Venture Capital Method takes a forward-looking

approach by estimating a startup’s current value

based on its projected exit value. It involves

forecasting future financial performance, applying an

appropriate exit multiple derived from comparable

market transactions, and discounting the future exit

value back to the present using a required rate of

return. Although this method is widely used by

venture capital investors for its focus on eventual

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

234

liquidity and ROI, it is highly dependent on

speculative future projections and assumptions about

market conditions at the time of exit, introducing

significant uncertainty into the valuation.

4.1.4 First Chicago Model

The First Chicago Model addresses the inherent

uncertainty of startup performance by employing a

scenario-based approach. Developed by Sahlman and

Scherlis (1987) and further elaborated by Damodaran

(2009), this method constructs multiple financial

projections—typically encompassing base, upside,

and downside scenarios—and then calculates a

probability-weighted valuation. By capturing a

broader range of potential outcomes, the First

Chicago Model provides a more nuanced view of risk

and reward. However, its reliance on accurate

probability assignments and multiple assumptions

can add complexity and potentially reduce precision.

Additionally, the accuracy of the valuation depends

heavily on the quality of the assumptions and

projections used (Cumming & Johan, 2013).

4.1.5 Discounted Cash Flow Method

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method is a

fundamental valuation technique used to estimate the

intrinsic value of an investment based on its expected

future cash flows. This method is particularly useful

for valuing companies, projects, and investments by

considering the time value of money and the

associated risks. The core principle of DCF is that the

value of an asset is equal to the present value of its

expected future cash flows.

The DCF valuation process involves several key

steps. First, future cash flows are forecasted based on

historical performance, industry trends, and

management projections. These cash flows typically

include revenues, operating expenses, taxes, changes

in working capital, and capital expenditures, resulting

in the free cash flow (FCF) available to the firm.

Next, an appropriate discount rate is

determined. Generally, the Weighted Average Cost of

Capital (WACC), which reflects the company's cost

of equity and debt, is adjusted for the risk profile of

the business.

The future cash flows are then discounted to their

present value using the WACC. In addition to the

forecast period, a terminal value is calculated to

account for the value of the business beyond the

forecast horizon. The terminal value can be estimated

using the perpetuity growth model or an exit multiple

approach.

Advantages of DCF Model:

1 Intrinsic Value: Focuses on a company’s

fundamentals and cash flow generation.

2 Flexibility: Adapts to different scenarios and

assumptions for sensitivity analysis.

3 Comprehensive: Accounts for the time value of

money and key value drivers.

Limitations of DCF Model:

1 Assumption Sensitivity: Small changes in inputs

(cash flows, discount rates, terminal values) can

significantly alter valuations.

2 Complexity: Requires detailed financial

projections and deep operational insights.

3 Data Intensive: Reliable data is crucial, making

it challenging for early-stage startups with

limited financial history.

5 PROPOSED SOLUTION

Traditional corporate finance valuation models, such

as the DCF approach, have yet to fully account for the

growing influence of ESG factors. The integration of

ESG considerations into startup valuation poses

unique challenges, particularly in terms of adjusting

the discount rate and projecting future cash flows.

However, given the increasing importance of

sustainable investing and its potential to reshape

investment decision-making, it is crucial to develop

more robust and inclusive valuation methodologies.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a

comprehensive solution that incorporates ESG

factors into the DCF model, ensuring a more accurate

reflection of a startup’s long-term value and risk

profile. The following methodology outlines a

systematic approach consisting of the following

steps:

1. Careful selection of ESG Ratings: Obtain ESG

ratings from reliable sources such as MSCI or

Sustainalytics. These ratings serve as a

foundation for quantifying the impact of ESG

factors on the valuation process.

2. Quantify ESG Impact: Translate ESG ratings

into a numerical score. For instance, MSCI

ratings can be converted into a scale from 0 to

100, allowing for easier integration into financial

models.

3. Calculate the Base Discount Rate: Begin with a

traditional calculation of the discount rate using

the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

or Cost of Equity (CoE). This base rate should

reflect traditional risk factors, including market

risk, company size, and financial leverage.

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG

235

4. Adjust for ESG Factors: Use regression analysis

to isolate the impact of ESG on the discount rate.

This step is crucial to avoid double counting by

ensuring that the ESG effect is distinct from other

risk factors. Our methodology prioritizes ESG

factors that provide additional, independent

insights into a startup's risk profile, beyond what

is already captured by traditional financial

metrics. For instance, social factors such as

employee retention rates and customer trust

scores are considered alongside governance

metrics that directly impact operational risk.

ESG factors related to reputational risk are only

considered if they significantly impact revenue

generation, rather than being assumed to be

reflected in the discount rate.

5. Integrate ESG Adjustments: Adjust the base

discount rate by applying an ESG premium or

discount.

5.1 Comprehensive Approach

5.1.1 Collect ESG Ratings

When collecting ESG ratings, companies typically

rely on specialized agencies and platforms that assess

and score companies based on their sustainability and

governance practices. Here are some key ESG rating

agencies and descriptions of how each one rates

companies:

1. MSCI ESG Ratings: MSCI evaluates companies

on their exposure to ESG risks and their ability

to manage them, using data from corporate

filings, media, and third-party sources. Ratings

range from AAA (leader) to CCC (laggard).

2. Sustainalytics: A subsidiary of Morningstar,

Sustainalytics provides ESG Risk Ratings from 0

(negligible risk) to 100+ (severe risk), assessing

companies' exposure to and management of ESG

risks.

3. FTSE Russell (FTSE4Good Index): FTSE

Russell rates companies on ESG practices with a

scale from 0 (low) to 5 (high), using over 300

indicators to create indexes like the FTSE4Good.

4. ISS ESG: ISS ESG Ratings focus on corporate

and investment practices, ranging from A+

(excellent) to D- (poor).

5. CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project): CDP rates

companies on environmental transparency and

performance, particularly on climate change and

deforestation, with grades from A to D-.

6. S&P Global ESG Scores: S&P Global rates

companies' sustainability practices out of 100,

with higher scores reflecting better management

of ESG risks and opportunities.

5.1.2 Quantify ESG Ratings

Normalizing ESG ratings from different agencies into

a consistent number range involves several steps. The

first step is selecting a common normalization range,

such as a 0-100 scale, where 0 represents the lowest

ESG performance and 100 is the highest. Next, it's

essential to understand the scoring systems of various

agencies, such as MSCI, Sustainalytics, FTSE

Russell, ISS ESG, CDP, and S&P Global, by

mapping their original scores to the chosen scale.

After that, each rating is normalized using a linear

transformation formula, which adjusts the original

scores to the 0-100 range. The proposed solution to

achieve this is as follows:

Step 1: Select a Normalization Range: We propose to

normalize all ratings to a 0-100 scale, where 0

represents the lowest ESG performance and 100 the

highest.

Step 2: Understand the Scoring Systems: Identify the

minimum and maximum values for each rating

system. For example:

• MSCI: CCC (lowest) to AAA (highest)

• Sustainalytics: 0 (negligible risk) to 100+

(severe risk) (Note: Lower is better here)

• FTSE Russell: 0 (low) to 5 (high)

• ISS ESG: D- (lowest) to A+ (highest)

• CDP: D- (lowest) to A (highest)

• S&P Global: 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest)

Step 3: Normalize Each Rating: Using a linear

transformation formula, we normalize the scores. The

formula for normalization to a 0-100 range is:

Normalized Score= Original Sore-Min Original

Score Max Original Score -Min Original Score x 100

For example: If a company has a rating of BBB in

MSCI ratings, which is between CCC (0) and AAA

(6):

Assign numerical values (e.g., CCC=0, B=2, BBB=3,

AAA=6)

Applying the formula, the Normalized Score=

(3−0)/(6−0)×100=50

Step 4: Combine the Scores: If you want a single

score representing all ratings, you can take the

average of the normalized scores:

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

236

(1)

where n is the total number of agencies.

(or)

Weighted Average: If you want to give more

importance to certain rating agencies, assign

weights and then calculate a weighted average:

(2)

Step 5: Refine and Adjust: The focus is on fine-tuning

the normalized ESG ratings to ensure they accurately

reflect the company's performance across different

dimensions and rating systems.

1. Consider Outliers: If one of the rating systems

provides a score that is significantly different

from the others, it might indicate a discrepancy

in how that particular agency evaluates ESG

factors compared to the others. For example, if

five rating agencies give a company an average

score of 70, but one agency gives a score of 30,

this outlier could skew the final combined score.

In such cases, you may need to adjust the impact

of the outlier, either by down-weighting its

influence or by investigating the reason for the

discrepancy to determine if it should be treated

differently.

2. Check for Consistency: After normalizing the

ratings, it's important to review the final scores to

ensure they align with the relative importance of

ESG factors according to your strategy. This

involves verifying that the normalization process

has accurately represented the weight and

significance of each rating system in relation to

the organization’s goals. For instance, if

environmental factors are more critical to a

company’s strategy, the final score should reflect

this emphasis rather than being overly influenced

by ratings that focus on other areas. This

consistency check helps to ensure that the

normalized ratings provide a meaningful and

balanced assessment of the company's ESG

performance.

5.1.3 Calculate the Base Discount Rate

For startups, the WACC formula might look like this:

WACC = EV x CoE+DV x CoD 1-Tax Rate (3)

Where

E: Market value of equity. The most common way to

determine the market value of equity for a startup is

through recent investment rounds or through any

other models listed in the Literature review section.

D: Market value of debt.

V: Total value of the company (equity + debt).

CoE: Cost of Equity, where beta is used.

CoD: Cost of Debt.

T: Corporate tax rate.

For example, let us assume that

• Market Value of Equity (E): $60 million

• Market Value of Debt (D): $40 million

• Total Value of the Company (V): $100 million

(calculated as $60 million + $40 million)

• Cost of Equity (CoE): 9.2% (from the calculation

below)

• Cost of Debt (CoD): 5% (before taxes)

• Corporate Tax Rate (T): 30%

WACC=(0.60*9.2%)+(0.40*3.5%)=6.92%

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is

6.92%. This represents the average rate of return that

the company needs to generate on its assets to satisfy

both equity and debt investors.

The Cost of Equity is the return that equity investors

expect for the risk they are taking by investing in the

company.

Cost of Equity (CoE) = R

f

+β×(R

m

−R

f

) (4)

Where

• R

f

: Risk-free rate, usually the return on

government bonds.

• R

m

: Expected market return.

• R

f

- R

m

: Market risk premium.

• β: Beta of the startup.

Beta (β) is crucial for evaluating startup risk and

return, particularly in calculating the Cost of Equity

(CoE) and Weighted Average Cost of Capital

(WACC). Since startups rely heavily on equity

financing, CoE becomes a key component of WACC.

Beta measures a company's volatility relative to the

market, and for startups—typically more volatile than

established firms—it is often estimated using

comparable companies or industry averages with risk

adjustments. A higher beta indicates greater risk,

requiring investors to demand higher returns, which

increases CoE. For instance, while a stable utility

company may have a beta near 1, a technology startup

may have a beta of 2 or more, reflecting twice the

market volatility. As startups face significant market

fluctuations, beta serves as a critical tool for assessing

their relative risk and investment potential.

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG

237

For example, let's assume that:

• Risk-Free Rate (R

f

)= 2% (e.g., yield on a 10-year

government bond)

• Beta (β)= 1.2 (indicating that the stock is 20%

more volatile than the market)

• Market Return (R

m

)= 8% (expected return of the

market)

• Market Risk Premium (R

m

- R

f

)= 6% (calculated

as 8% - 2%)

Then

CoE=2%+1.2*6%=2%+7.2%=9.2%

The Cost of Equity (CoE) is 9.2%.

This means investors expect a 9.2% return on equity

to compensate for the risk they are taking.

The Cost of Debt (CoD) represents the effective rate

a company pays on its borrowed funds. It's a crucial

component of the Weighted Average Cost of Capital

(WACC) and reflects the interest expense associated

with debt financing. Here's the formula and how it's

typically used:

CoD=Total Interest Expense / Total Debt (5)

Where:

• Total Interest Expense: The total amount of

interest the company pays on its debt over a

specific period.

• Total Debt: The total amount of debt the

company has outstanding.

After-Tax Cost of Debt: Since interest expenses on

debt are tax-deductible, the after-tax cost of debt is

often used in WACC calculations. The formula for

the after-tax cost of debt is:

CoD (after tax)=CoD×(1−T) (6)

where T: The corporate tax rate.

WACC serves as a benchmark for evaluating overall

company performance and investment decisions. It

represents the minimum average return the company

needs to generate across all its investments to satisfy

both equity investors and debt holders. It not directly

about satisfying the 9.2% expected by equity

investors; rather, it's about ensuring the company

meets the blended costs of its entire capital structure.

Here's a table showing different scenarios for ROI in

relation to CoE and WACC with examples:

Table 1: ROI vs. CoE vs. WACC.

5.1.4 Adjust for ESG Factors

Ensuring ESG adjustments do not overlap with

traditional risk components is crucial to maintaining

accurate valuations. Double counting can distort a

company’s risk profile, leading to over- or

underestimation.

Additive Adjustment: Applies a fixed ESG premium

or discount but lacks precision as it ignores ESG’s

specific relationship with the discount rate.

Scenario Analysis: Assesses ESG impact under

different conditions but is subjective and assumption-

driven.

Regression Analysis: A data-driven approach that

isolates ESG's effect on the discount rate, minimizing

double counting and improving accuracy. Unlike

other methods, regression quantifies the unique

contribution of ESG while controlling for traditional

risk factors—such as market risk, company size, and

leverage—that are already embedded in the discount

rate. Our approach will utilize Multicollinearity

Testing where Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

analysis is used to detect if ESG metrics overlap with

traditional risk factors. A low VIF score ensures ESG

variables are not duplicating risk already accounted

for in the model. The proposed solution will use a

Multiple Linear regression model as shown below

since there are two or more independent variables.

Step 1: In our proposed solution we will write the

Discount Rate (i.e. the Regression Equation) as

follows:

Discount Rate = 𝛼 + b

1

⋅Market Risk + b

2

⋅Company

Size + b

3

⋅Leverage + b

4

⋅ESG Score + 𝜖 (7)

Where:

Scenario ROI vs. CoE ROI vs. WACC Explanation Example

Scenario 1:

ROI > CoE and

ROI > WACC

ROI > CoE ROI > WACC

The company generates

sufficient returns to meet

and exceed both the equity

and the overall capital cost.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 7%, ROI

= 10%. This creates value for

both equity and debt holders.

Scenario 2:

ROI = CoE and

ROI > WACC

ROI = CoE ROI > WACC

The company meets equity

investors' expectations and

generates enough return for

the entire capital structure.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 7%, ROI

= 9.2%. The company satisfies

equity investors and creates

value for debt holders.

Scenario 3:

ROI > CoE but

ROI < WACC

ROI > CoE ROI < WACC

The company satisfies

equity investors but fails to

meet the total capital cost,

not creating value for debt

holders.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 10%,

ROI = 9.5%. The company

satisfies equity investors but

doesn’t create value for debt

holders.

Scenario 4:

ROI = CoE and

ROI = WACC

ROI = CoE ROI = WACC

The company exactly meets

both equity investors'

expectations and the overall

capital cost. No value is

created, but no value is lost.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 9.2%,

ROI = 9.2%. The company

breaks even; equity and debt

holders are satisfied, but no

value is added.

Scenario 5:

ROI < CoE and

ROI < WACC

ROI < CoE ROI < WACC

The company fails to meet

both equity investors'

expectations and the total

capital cost, creating no

value for either.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 7%, ROI

= 6%. The company fails to meet

expectations for both equity and

debt holders.

Scenario 6:

ROI < CoE but

ROI > WACC

ROI < CoE ROI > WACC

The company fails to meet

equity investors'

expectations, but still

generates enough return to

satisf

y

debt holders.

CoE = 9.2%, WACC = 7%, ROI

= 8%. The company satisfies

debt holders but not equity

investors.

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

238

• α: Intercept term; the value of discount rate when

all other independent factors are zero.

• b: Coefficients for each variable; showing the

effect of each independent variable on the

discount rate

• Market Risk: Typically represented by beta (β)

• Company Size: Measured by market

capitalization

• Leverage: Measured by the debt-to-equity ratio

• ESG Score: The ESG score of the company

• ε: Error term

We will apply a multiple linear regression model

using hypothetical data to demonstrate the approach.

By refining the discount rate with these additional

factors, we aim to offer a more nuanced

understanding of how ESG influences risk and return

dynamics in startup investments.

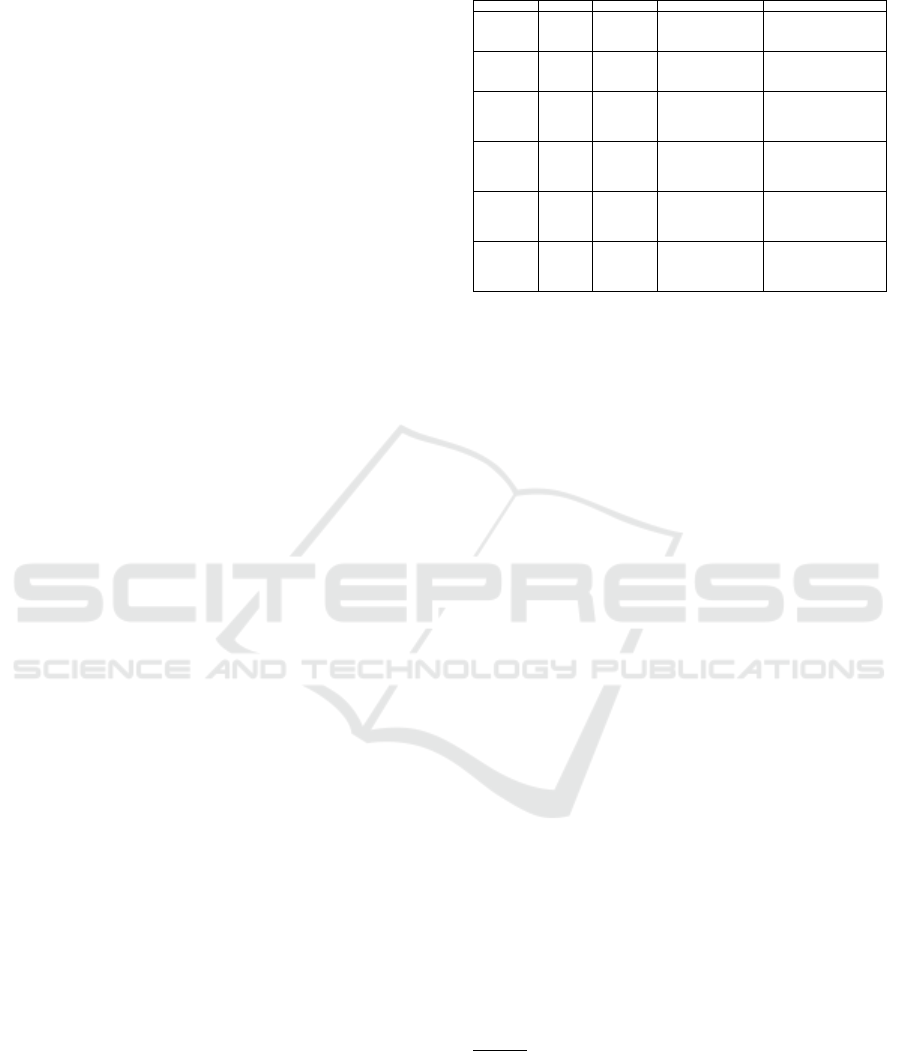

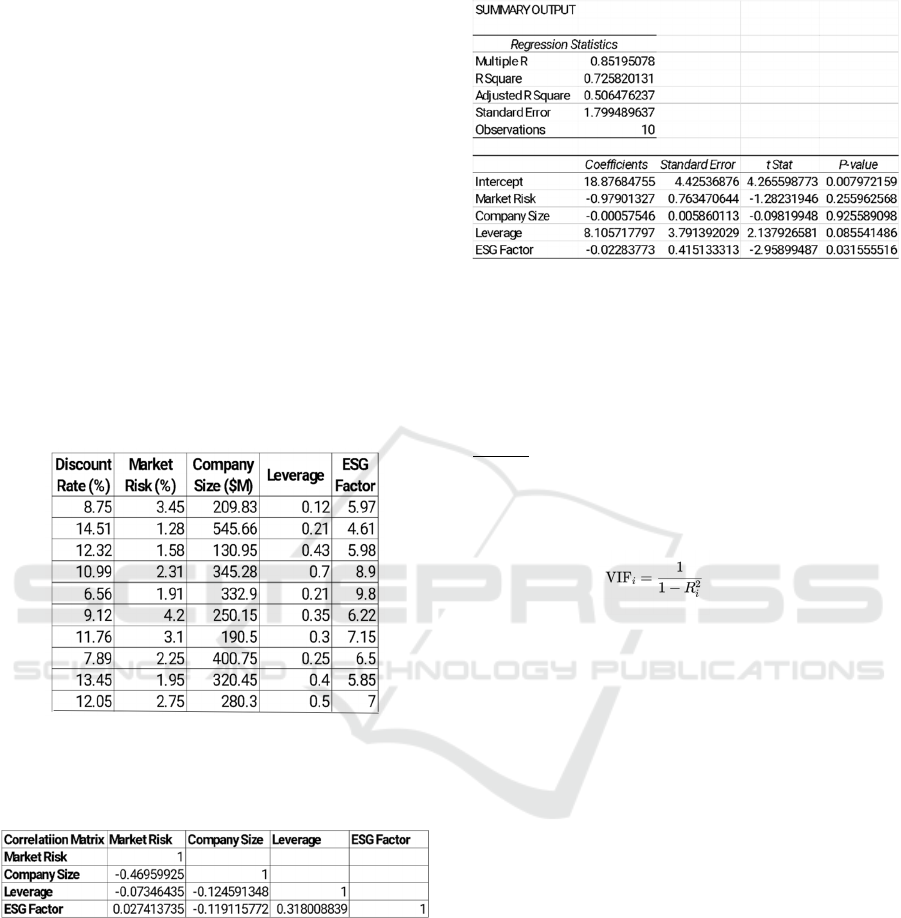

Table 2: Data from 10 startup companies.

Using Microsoft Excel, we obtain the Correlation

between the independent variables:

Table 3: Correlation Matrix for the Independent Variables.

Using the Microsoft Excel Regression Analysis

feature with the following input,

Y Range: Range for the dependent variable (Discount

Rate)

X Range: Select the range for the independent

variables (Market Risk, Company Size, Leverage,

ESG Score), we obtain the following results:

Table 4: Regression Analysis Output.

and

Intercept (α): 18.88

Market Risk (β₁): -0.98

Company Size (β₂): -0.0006

Leverage (β₃): 8.11

ESG Score (β₄): -0.023

Step 2: To again confirm there is no multicollinearity,

we calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF) for

each of the independent variables. For each

independent variable X

i

in a regression model, VIF is

calculated as:

(8)

Where R

i

2

value is obtained from regressing the

independent variable X

i

against all other independent

variables in the model.

Interpreting VIF Values

• VIF = 1: There is no correlation between the

independent variable X

i

and the other

independent variables. There is no

multicollinearity.

• 1 < VIF < 5: Moderate correlation exists, but it is

usually not problematic. This is often considered

an acceptable range.

• VIF > 5: Indicates a high correlation between the

independent variable and the other independent

variables, suggesting significant

multicollinearity.

The VIFs for the above model are calculates as shown

below:

Market Risk VIF = 1.332

Company size = 1.332

Leverage =1.147 and

ESG = 1.121

Since all the VIFs are below 5, it indicates that there

is no significant multicollinearity among the

independent variables. This suggests that the

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG

239

independent variables are not highly correlated with

each other, and we can proceed with the regression

analysis without concerns about multicollinearity

affecting our results.

Step 3: Next, we will look at the p-values from the

regression and its significance. In regression analysis,

the p-value is the measure used to determine the

statistical significance of the independent variable

assuming that the null hypothesis is true.

ESG Factor:

• Null Hypothesis (H₀): The ESG factor has

no significant effect on the discount rate.

• Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): The ESG

factor has a significant effect on the discount

rate.

Company Size ($M):

• Null Hypothesis (H₀): Company size has no

significant effect on the discount rate.

• Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Company size

has a significant effect on the discount rate.

Market Risk (%):

• Null Hypothesis (H₀): Market risk has no

significant effect on the discount rate.

• Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Market risk has

a significant effect on the discount rate.

Leverage:

• Null Hypothesis (H₀): Leverage has no

significant effect on the discount rate.

• Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Leverage has a

significant effect on the discount rate.

A Low p-value (≤ significant level) Indicates strong

evidence against the null hypothesis, suggesting that

the independent variable is statistically significant in

explaining the variability of the dependent variable.

High p-value (> significant level): Indicates weak

evidence against the null hypothesis, suggesting that

the independent variable may not be a significant

predictor of the discount rate. For the above data, with

5% significance level,

1. Market Risk: P-value = 0.256: This is greater

than 0.05, suggesting weak evidence against the

null hypothesis. The Market Risk is not

statistically significant, implying it does not have

a strong effect on the discount Rate.

2. Company Size: P-value = 0.926: This is much

greater than 0.05, indicating very weak evidence

against the null hypothesis. The Company Size is

not statistically significant.

3. Leverage: P-value = 0.0855: This is slightly

above the 0.05 threshold. It suggests moderate

evidence against the null hypothesis, but the

Leverage is not statistically significant at the 5%

level. However, it might be considered

significant at a more lenient level.

4. ESG Factor: P-value = 0.0316: This is less than

0.05, indicating strong evidence against the null

hypothesis. The ESG factor is statistically

significant and can have a strong effect on the

Discount Rate.

5.1.5 Integrate ESG Adjustment

Our regression equation is = 𝛼 + b

1

⋅Market Risk +

b

2

⋅Company Size + b

3

⋅Leverage + b

4

⋅ESG Score + 𝜖

In the above regression, we calculated the coefficient

of ESG b

4

as -0.023

ESG Adjustment = ESG score * b

4

= 80*(-0.023) = -

1.84

We started with 6.92 as the original Discount

Rate (from the WACC calculation in 5.1.3)

So, the adjusted Discount Rate with ESG Factor

adjustment will be 6.92-1.84 = 5.08

Because the ESG coefficient is negative, there

is an inverse relationship between the discount rate

and ESG score, which means that companies with

higher ESG rating will have a lower discount rate and

higher valuation, which reflects the company’s

commitment to environment, social, and governance

responsibilities that mitigate risk and hedge against

market disturbances. With the lower discount rate, the

DCF analysis will show a higher valuation with an

ESG score of 80.

5.1.6 Consideration While Using the

Regression Analysis

Multicollinearity: Ensure no high correlation between

independent variables to avoid redundancy and

inaccurate estimates. For example, including both

"total assets" and "total liabilities" might distort

estimates if they are highly correlated.

Variable Overlap: Avoid including variables that

measure the same concept to prevent double

counting.

Correct Model Specification: Include relevant

variables and exclude irrelevant ones. For instance,

omitting "industry sector" when studying company

size’s effect on profitability may misattribute sector

effects to company size.

Avoid Proxy Variables: Be cautious when using

proxy variables, like "employee satisfaction scores"

for "organizational culture," as they may overlap with

other variables, leading to double counting.

Data Quality: Ensure accurate and consistent data

to prevent errors and unintended double counting.

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

240

6 FUTURE RESEARCH

1. Nonlinear Models: Investigate polynomial

regressions or machine learning techniques to

capture complex interactions between ESG

factors, market risk, and discount rates.

2. Longitudinal Analysis: Examine how ESG

factors influence discount rates over time,

contrasting early-stage with mature startups.

3. Policy Impact: Analyze the effects of ESG-

related regulations (e.g., carbon taxes, subsidies)

on startups’ cost of capital for regional and

industry-specific insights.

4. Behavioral Finance: Incorporate ESG sentiment

indices and investor preferences to better

understand market perceptions and valuation

dynamics.

5. Sensitivity and Scenario Testing: Perform

sensitivity analyses to assess how changes in

ESG factors or market conditions affect discount

rates and valuations.

6. Case Study: Revalue a startup using an ESG-

adjusted DCF model (using data from

PitchBook) to compare original and adjusted

valuations and illustrate ESG’s impact.

REFERENCES

Babu, A., Arikutaram, C., & Mathews, A. (2023). Risk

factor summation method. In A practical guide for

startup valuation (pp. 223–240). Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35291-1_11

Babu, A., Mathews, A., & Chinmaya, A. M. (2023).

Dave Berkus method. In A practical guide for startup

valuation (pp. 209–222). Springer. https://doi.org/

10.1007/978-3-031-35291-1_10

Berkus, D. (1994). Valuation of start-ups. Venture Capital

Review.

Cumming, D., & Johan, S. (2013). Venture capital and

private equity contracting: An international perspective.

Elsevier.

Damodaran, A. (2006). Damodaran on valuation: Security

analysis for investment and corporate finance (2nd ed.).

Wiley.

Damodaran, A. (2009). Valuing young, start-up and growth

companies: Estimation issues and valuation challenges.

Stern School of Business, New York University.

E Investing for Beginners. (2024). Relative valuation-Pros

and cons of the most common form of valuation.

Retrieve from https://einvestingforbeginners.com/

relative-valuation-daah/

Faster Capital. (2024). Advantages and disadvantages of

relative valuation compared to other valuation methods.

Retrieved from https://fastercapital.com/topics/

advantages-and-disadvantages-of-relative-valuation-

compared-to-other-valuation-methods.html

Feld, B., & Mendelson, J. (2016). Venture deals: Be

smarter than your lawyer and venture capitalist. John

Wiley & Sons.

Financial Modeling Prep. (2024). Relative valuation vs.

intrinsic valuation: A comprehensive comparison of

two fundamental approaches. Retrieved from

https://site.financialmodelingprep.com/education/other

/Relative-Valuation-vs-Intrinsic-Valuation-A-

Comprehensive-Comparison-of-Two-Fundamental-

Approaches

FreshBooks. (2024). Relative valuation model: Definition

& an overview. Retrieved from

https://www.freshbooks.com/glossary/financial/relativ

e-valuation

Gompers, P., Kaplan, S. N., & Mukharlyamov, V. (2016).

What do private equity firms say they do? Journal of

Financial Economics, 121(3), 449–476.

Hull, J. C. (2018). Options, futures, and other derivatives

(10th ed.). Pearson.

Inrate. (2024). How to integrate ESG into your business

strategy? Retrieved from https://inrate.com/blog/how-

to-integrate-esg-into-business/

Investopedia. (2024a). Relative valuation: How to value

other stocks. Retrieved from

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/11/relati

ve-valuation-stocks-valuing-stocks.asp

Investopedia. (2024b). Relative valuation model:

Definition, steps, and types of models. Retrieved from

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/relative-

valuation-model.asp

Koller, T., Goedhart, M., & Wessels, D. (2015). Valuation:

Measuring and managing the value of companies (6th

ed.). Wiley.

Lions Financial. (2024). Methods for valuing a startup for

venture capital financing. Retrieved from

https://lions.financial/what-are-the-methods-for-

valuing-a-startup-for-venture-capital-financing/

McKinsey & Company. (2024). Five ways that ESG creates

value.

Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/

McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Strategy%20and%2

0Corporate%20Finance/Our%20Insights/Five%20way

s%20that%20ESG%20creates%20value/Five-ways-

that-ESG-creates-value.ashx

Payne, B. (2011). The definitive guide to raising money

from angels. Lulu Press.

Payne, B., & Marom, D. (2018). The startup valuation

report. Angel Capital Association.

Sahlman, W. A., & Scherlis, D. R. (1987). A method for

valuing high-risk, long-term investments: The "venture

capital method". Harvard Business School Background

Note 288-006.

Source Scrub. (2024). Definition of relative valuations.

Retrieved from https://www.sourcescrub.com/post/

definition-relative-valuation

Valutico. (2024). VC method: Valutico's easier way to

value startups. Retrieved from https://valutico.com/vc-

method-launches/

Unicorn Illusions: A Novel Approach to Startup Valuation Using ESG

241

Venionaire. (2024). Venture capital method for company

valuation. Retrieved from

https://www.venionaire.com/venture-capital-method/

Wall Street Prep. (2024). Venture capital valuation VC

method template + example. Retrieved from

https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/vc-

valuation-6-steps-to-valuing-early-stage-firms-excel-

template/

Wall Street Prep. (2024). WACC | Weighted average cost

of capital. Retrieved from

https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/wacc/

FEMIB 2025 - 7th International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

242