The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students'

Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An

Analysis of Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

Andrea Balbo

1a

, Alice Barana

2b

, Giulia Boetti

2c

, Marina Marchisio Conte

2d

and Sara Omegna

2e

1

Department of Humanities, University of Turin, Via Sant’Ottavio 20, 10124 Torino, Italy

2

Department of Molecular Biotechnology and Health Sciences, University of Turin, Piazza Nizza 44, 10153 Torino, Italy

Keywords: Academic Success, Distance Learning, Digital Learning Environment, Student Motivation, Tutoring.

Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic has increased educational poverty, especially among students from low

socioeconomic backgrounds. To address this problem, the compiti@casa project, initiated by the University

of Turin in collaboration with the De Agostini Foundation, has provided a distance tutoring service for lower

secondary school students, i.e., aged between 11 and 14, with learning difficulties. This study examines the

effectiveness of tutoring in improving students' learning skills and attitudes by analysing tutors' responses to

a final questionnaire they completed for each student they tutored, both in Mathematics and Italian.

Specifically, it aims to address two research questions: “What strategies did the tutors consider effective in

improving the skills and attitudes of each student?” (RQ1) and “Is the impact of different tutoring practices

visible on students' learning approach and personal improvement?” (RQ2). The results show significant

improvements in students' motivation, autonomy and confidence, particularly for those who were more

actively engaged in an interactive and personalised approach. However, there are difficulties in engaging less

motivated students or those with attendance problems. The study concludes by highlighting the importance

of personalised teaching strategies to maximise the benefits of tutoring.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2020, in response to the educational fragility

exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the

DELTA (Digital Education for Learning and

Teaching Advances) research group of the University

of Turin, in collaboration with the De Agostini

Foundation, launched the project “compiti@casa:

curing educational fragility”. Funded by the same

Foundation, this initiative aligns with the objectives

of the Italian NRRP (National Recovery and

Resilience Plan) as part of the Next Generation EU

programme agreed upon with the European Union to

address the pandemic-induced crisis. The NRRP is

based on three pillars: digitalisation and innovation,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2227-7217

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9947-5580

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5329-3378

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1007-5404

e

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9796-5882

ecological transition, and social inclusion (Ministero

dell’Istruzione e del Merito, 2022). Additionally, the

project adheres to the DigCompEdu (Digital

Competence Framework for Educators) framework

developed by the European Commission’s Joint

Research Centre (JRC) in 2017 to promote the

development of educators' digital competencies.

The broader context shaped by the COVID-19

pandemic caused unprecedented disruptions to

education worldwide. School closures affected more

than 1.6 billion learners, seriously affecting student

learning (Unicef, 2021). Although most countries

offered distance learning opportunities, the quality

and accessibility of these programs varied widely and

only partially replaced face-to-face teaching. By the

594

Balbo, A., Barana, A., Boetti, G., Conte, M. M. and Omegna, S.

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project.

DOI: 10.5220/0013430700003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 594-605

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

end of 2021, many schools remained closed, putting

millions of children and young people at risk of

permanently dropping out of school. Evidence shows

significant learning loss, with marginalised students

facing the greatest challenges (Unicef, 2021).

The pandemic further deepened educational

inequality, compounding economic hardship.

Educational poverty - a condition in which young

people lack opportunities to fulfil their potential and

aspirations - has worsened (Save the Children, 2022).

This situation is especially severe for students from

low-income families with limited educational

attainment (INVALSI, 2021a; Moscoviz & Evans,

2022).

In this context, the compiti@casa project was

born with the aim of providing remote support to

lower secondary school students (in Italy, “Scuola

Secondaria di Primo Grado", where students are

between 11 and 14 years old) who need help with

homework. Specifically, it targets students facing

learning difficulties, low autonomy, and lack of

motivation, often compounded by socioeconomic

disadvantage and the absence of adult support during

homework. Its primary goal is to support learning

recovery in scientific (mainly Mathematics) and

humanistic (mainly Italian, i.e., L1 for native speakers

and L2 for others) subjects through digital

technologies and the potential of a digital learning

environment. In tutoring activities, tutors can adopt

different strategies to optimise the students' learning

experience, adapting their approach to individual

needs. Strategies that can foster effective tutoring

include promoting support and interaction, enhancing

motivation, supporting autonomy and encouraging

active engagement. Strengthening tutor-student trust

and friendship, improving concentration and attention

and balancing exercises with theoretical learning are

other methods that can effectively support struggling

students. Interactivity also plays a crucial role in

keeping students' attention and fostering more

profound understanding.

Given the positive impact of the project in

supporting students in their learning path, it has

continued to evolve and expand, accessing more

students each year and reaching its fifth edition in the

2024/2025 academic year. This paper aims to

investigate the effectiveness of tutoring approaches in

improving students' skills and attitudes, considering

the 2022/2023 edition.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

The literature shows that low academic achievement,

especially among students from disadvantaged and

ethnic minority backgrounds, is one of the main

factors contributing to school dropout (Szabó, 2018).

This problem is influenced by both internal factors,

such as confidence, self-esteem, motivation, attitude,

cognitive style and anxiety, and external factors, such

as school environment, family support and

socioeconomic status (Hossein-Mohand & Hossein-

Mohand, 2023; Raj Acharya, 2017; Fagnani et al.,

2020). In this context, the OCSE PISA 2022 survey

on equity in education highlighted the importance of

ensuring that all students can reach their full potential

regardless of their background. In particular, it

measured the percentage of 15-year-olds achieving at

least a basic level in key subjects: on average, 69% of

students in OCSE countries achieved at least a basic

level in Mathematics and around 75% in Reading and

Science. As Mathematics was the focus of PISA

2022, equity was assessed in this cycle by examining

the extent to which socioeconomic status explains

differences in student performance in Mathematics.

The survey also highlighted other achievement gaps,

including those related to gender and immigrant

background. It showed that about 31% of the

variation in student performance can be attributed to

differences in education systems, particularly in

terms of organisation, funding and resource

allocation (OCSE PISA, 2022). Metacognition, i.e.

the ability to reflect, plan, monitor and evaluate one's

own learning processes, is a strong predictor of

academic success (Hrbáčková et al., 2012).

Therefore, addressing aspects such as motivation,

self-esteem, self-awareness, the development of

metacognitive skills and self-evaluation can

positively impact school performance and help

reduce the risk of dropping out. In this regard,

Dietrichson et al. (2017) sought to examine the

effectiveness of academic interventions designed to

improve the achievement of primary and secondary

school students from low socioeconomic status (SES)

backgrounds. Focusing on students for whom at least

50% come from low-income, low-education, or

minority households, the review excludes studies on

high school and preschool settings to maintain focus

on mandatory education. The aim is to provide

evidence for policymakers on which intervention

types—such as tutoring, cooperative learning, and

progress monitoring—are most effective in

narrowing the achievement gap between low-SES

and higher-SES students. The findings reveal that

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

595

tutoring, feedback, and cooperative learning produce

positive, statistically significant results in academic

performance for low-SES students, though

effectiveness varies. The authors highlight the need

for further research on long-term impacts and cost-

effectiveness, stressing that while these interventions

are promising, local factors play a crucial role in their

success.

One approach highlighted in the literature for

fostering these skills is, as anticipated, tutoring,

which is defined as "people who are not professional

teachers helping and supporting the learning of others

in an interactive, purposeful and systematic way"

(Topping, 2000). It is most usually done on a one-to-

one basis or in a pair. Tutors could include parents or

other adult carers, brothers and sisters, other students

from the peer group, and various kinds of volunteers.

Then came peer tutoring, a form of tutoring in which

individuals from the same peer group, such as

classmates or students of a similar age, help each

other learn (Topping, 2000). The tutor does not need

to be an expert, but it is often helpful if they have

slightly more knowledge than the tutee. Peer tutoring

is seen as an interactive and collaborative method

which promotes learning for both the tutor and the

tutee (Topping, 2000).

In this regard, several studies in the literature

examine the effectiveness of tutoring in improving

students' skills and attitudes throughout their school

careers. For example, Pasion (2024) investigated the

impact of peer tutoring on the academic achievement

of secondary school students in Mathematics,

focusing on specific topics such as sequences,

polynomials, and polynomial equations. She

concluded that peer tutoring significantly improved

students' understanding of Mathematics and found a

strong positive correlation between the perceived

benefits of peer tutoring and students' academic

performance.

Gortazar, Hupkau and Roldán-Monés (2024)

sought to provide the scientific community with

experimental evidence on the effectiveness of an

eight-week, fully online Mathematics tutoring

programme designed to support disadvantaged

children. Specifically, they wanted to measure the

programme's impact on academic achievement

(Mathematics test scores and grades) and social-

emotional outcomes, such as aspirations and self-

reported effort. The study concluded that online

tutoring significantly improved students'

performance in Mathematics, increasing their

Mathematics grades by 0.49 SD.

Numerous projects have also been implemented

in Italy to combat school failure and promote lower

secondary students' academic success. Among these,

the Fuoriclasse project (Ambrosini & De Simone,

2015), active for a decade (from 2012 to 2022),

offered out-of-school tutoring in the presence of

students from disadvantaged backgrounds and at risk

of dropping out of school in several Italian regions.

The project aimed to intervene both at the cognitive

level through peer tutoring and at the motivational,

metacognitive and relational levels through

workshops and extracurricular activities. The

project's integrated approach focused on students,

teachers and families and included innovative

activities such as motivational workshops and peer

education sessions to build self-esteem and increase

engagement. Fuoriclasse also included school camps,

which allowed students to work in non-traditional

environments, fostering a sense of belonging and trust

in school. This participatory approach not only

improved their academic motivation but also

strengthened their bonds with the school community.

The impact of Fuoriclasse was carefully monitored

through a quasi-experimental design to verify its

effectiveness in reducing dropout rates and increasing

students' commitment to education, with results

showing increased student motivation and

achievement in all participating schools.

Another example is the Scuola dei Compiti project

(Barana et al., 2017; Giraudo et al., 2014),

implemented in Turin from 2013 to 2020 with the

support of the City of Turin and in collaboration with

the University of Turin. This project provided

afternoon sessions in small groups, led by university

students as tutors, to support at-risk middle and high

school students in various subjects, including Italian,

Latin, Mathematics, Science and Foreign Languages.

Although the activities were mainly face-to-face,

some tutors enriched them with digital resources in a

Digital Learning Environment (DLE). Compared to a

classical learning environment (Wilson, 1995), i.e. a

place where the student is involved and an

environment where he/she operates, a DLE indicates

a learning ecosystem in which teaching, learning, and

the development of competence are fostered in

classroom-based, online or blended settings. It is

composed of a human component, a technological

component, and the interrelations between the two

(Barana & Marchisio, 2022). DLEs are provided and

managed by a Learning Management System (LMS),

which is also responsible for identifying and

evaluating learning objectives, tracking the students'

progress, and collecting data to monitor the learning

process. According to the literature (see, e.g., Barana

and Marchisio, 2022), a DLE supports learning

through different functions:

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

596

● Instructional support: allows teachers and

students to design, modify and manage

educational resources and activities.

● Access to materials: provides users with

accessible learning materials and activities

anytime.

● Data collection: collects quantitative and

qualitative information about activities, use

of materials and participation.

● Data analysis and feedback: processes the

data collected and provides feedback to

learners on the results achieved and to

teachers on designing future activities.

Therefore, they are widely used to support online

educational processes, but the literature has shown

how they also implement classroom learning (Barana

& Marchisio, 2022). In summary, a DLE enables the

creation of an interactive and accessible learning

environment, supports collaboration between

students, and promotes formative assessment,

providing feedback to both students and teachers to

monitor and improve the educational journey.

As it emerged in the experiences above, tutoring

actions are shaped by students' individual needs. In

particular, the online tutoring carried out within the

compiti@casa project can be conceptualised as

"student-centred online one-to-one tutoring" (Zhang

et al., 2021). Although the structure in our case

involves a two-to-one student-to-tutor ratio, the small

group format ensures that the intervention remains

highly focused on the students, maintaining their

needs and learning as the core of the process. Small-

group tutoring contexts allow for a more personalised

and interactive approach, thereby improving attention

and comprehension. The effectiveness of such

tutoring models largely depends on the strategies

employed by tutors. As highlighted by Zhang et al.

(2021), the success of online tutoring is contingent

upon adopting teaching methods that actively engage

students, foster autonomy, and build a supportive

learning environment. These findings align with the

principles of student-centred learning, fostering

adaptability, confidence, active engagement and

autonomy as key factors in enhancing educational

outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

3 SETTING AND RESEARCH

METHODOLOGY

3.1 The Compiti@Casa Project

The compiti@casa project (Balbo et al., 2024), which

literally means "homework@home", is the result of a

collaboration between the University of Turin and the

De Agostini Foundation, inspired by the experience

of the Scuola dei Compiti project (Barana et al., 2017;

Giraudo et al., 2014). This initiative pursues several

educational objectives: catching up, overcoming

learning difficulties, increasing motivation to study,

reducing the number of early school leavers and

strengthening the skills of the students involved. The

intervention includes support for distance learning,

divided into four hours per week within a DLE. It is

aimed at students from peripheral schools located in

contexts characterised by particularly critical issues

(Balbo et al., 2024). The project's third edition,

covering the academic year 2022/2023, involved

approximately 290 students from six different Italian

cities (Milan, Naples, Novara, Rome, Palermo and

Turin) and 105 tutors. The tutors were students from

the University of Turin, adequately trained in

innovative methods and technologies for education

(Barana et al., 2021) and supported by professors and

members of the Delta Research Group. A distinctive

element of the project is, therefore, the minimal age

difference between tutors, who are undergraduate and

master students, and the beneficiary students, who are

between 11 and 14 years old. This aspect favours a

more empathetic interaction and makes the

experience highly formative for both students and

tutors (Balbo et al., 2024).

Each group of students typically consists of two

—though occasionally one or three—and receives a

total of 30 hours of tutoring in scientific subjects

(mainly Mathematics) and 30 hours in humanities

(mainly Italian, i.e., L1 for native speakers and L2 for

others), scheduled over two non-consecutive days per

week. Each group is assigned two tutors: one

specialised in scientific disciplines and the other in

humanities. Tutoring sessions are conducted weekly,

with two-hour web conferences per discipline, from

February to May. In these meetings, students can

receive support in carrying out the homework

assigned by their teachers at school, but not only. For

many of them, it is also an important opportunity to

express their doubts in a more relaxed and non-

judgemental environment. This aspect is particularly

significant for those who, for lack of time during

lessons or due to shyness, are unable to ask questions

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

597

or clarify their uncertainties in class. Moreover, these

moments allow students to challenge themselves

more consciously, confronting their difficulties and

learning how to recognise and overcome them.

In the DLE, courses dedicated to both science and

humanities subjects are created for each pair of

students. Within these courses, students can access a

variety of tools useful for their learning. The forum,

for instance, is a versatile environment: on the one

hand, tutors can use it to communicate service

information, such as updates on the calendar; on the

other hand, students are encouraged to write to report

doubts or problems. This facilitates an open and

continuous dialogue, both between tutors and

students and between the students themselves.

The DLE also hosts an attendance management

system, a tool that allows tutors to record student

attendance at each meeting accurately. This system

ensures timely monitoring and enables the tutors to

check whether the students participating in the project

are taking advantage of the opportunity offered.

In addition, teaching materials can be downloaded

from each course: concept maps specially created by

the tutors to support students in their studies, links to

materials already available online, documents

prepared during the tutoring sessions, interactive

quizzes and materials with immediate feedback to

help students assess and consolidate their knowledge

(Barana et al., 2019a; Barana et al., 2019b; Barana et

al., 2019c; Barana et al., 2020b) and other open

educational resources. Interactive materials are

particularly valuable, since they can increase the

engagement level of students who show a low interest

in subjects they are learning (Barana et al., 2020a).

This variety of tools and contents contributes to

creating a stimulating and flexible learning

environment that is adaptable to the different needs of

the students.

In addition, the DLE is integrated with

BigBlueButton, an open-source web conferencing

system that facilitates access to tutoring sessions

through its compatibility with major learning

management systems. This integration offers

significant benefits, such as allowing students to

access virtual classes without entering an email

address and eliminating the need for manual

permissions. Furthermore, students and tutors can

participate in the same session, even if they belong to

different organisations (e.g. university or school

domains). This reduces technical barriers and allows

all participants to focus on the learning experience.

The project develops through four main phases:

1. in November, the DLE is prepared, preliminary

meetings are held between professors and

organisers, followed by the selection and

enrolment of students;

2. in December and January, the teachers are

trained through a course on innovative teaching

tools and methodologies, the tutors are selected

through a public call for tenders, and they are

trained;

3. from February to May, the tutoring activities

take place, with weekly meetings aimed at the

two disciplinary areas;

4. in May, the final event takes place at the

University of Turin, representing an

opportunity for comparison and exchange

between all the participants in the project.

3.2 Research Method

At the end of the activities carried out as part of the

2022/2023 edition of the compiti@casa project, we

collected the answers given by the science and

humanities tutors to the final questionnaire about the

students they had supported. First of all, each tutor

filled in a separate questionnaire for each student

assisted, which means that we collected

approximately two questionnaires per student, one for

Italian (L1 and L2) and one for Mathematics. From

the analysis of these responses, in this paper, we set

out to answer the following questions:

● RQ1.What strategies did the tutors consider

effective in improving the skills and

attitudes of each student?

● RQ2. Is the impact of different tutoring

practices visible on students' learning

approach and personal improvement?

To answer RQ1, the answers to the following

open-ended question posed to tutors were analysed:

‘Which aspects did you find particularly useful and

effective for the student?’. After careful reading,

recurring themes were identified, which allowed us to

classify the responses according to the main topics

covered. When more than one theme emerged in the

same answer, they were all considered. Once

classified, the frequency of each theme within the

responses was calculated to provide information on

the aspects that most commonly tutors considered

valuable and effective.

Above all, to ensure the reliability of the

qualitative analysis, all responses to the open-ended

questions were initially analysed by one researcher. A

second researcher then independently analysed a

subset of the responses. Any discrepancies between

the two analyses were discussed in detail, and a third

researcher joined the discussions to validate the

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

598

coding process. Once agreement was reached on the

coding categories, the first researcher analysed the

responses again, incorporating feedback from the

discussions. This triangulation process helped ensure

the consistency and accuracy of the qualitative data.

Finally, the frequency of each identified theme was

recalculated based on the validated coding categories,

providing a more reliable measure of tutors' most

commonly perceived effective strategies.

To answer RQ2, the following questions on

cognitive and metacognitive aspects were considered.

Tutors could respond using a Likert scale of 1 to 5,

where 1 is ‘Not at all’ and 5 is ‘To a great extent’.

● [D1] Does the student show motivation?

● [D2] Does the student demonstrate

competence in the subject?

● [D3] Does the student demonstrate the

ability to learn?

● [D4] Does the student study independently?

● [D5] Does the student show confidence in

his/her abilities?

● [D6] Does the student have self-esteem?

● [D7] Does the student identify the real

causes of his/her difficulties?

● [D8] Is the student aware of his/her

strengths?

Each D-question was asked twice: the tutors

answered once considering the beginning of the

project and once considering the end of the project. In

this way, tutors were asked to reflect on the level of

each learner recorded at the beginning and end of the

project to highlight the variation in each aspect for

each learner. This allowed us to examine the

effectiveness of tutoring in improving students' skills

and attitudes.

The average of the variations of the ratings for

each question was then calculated. Only the scores of

students for whom the tutor indicated that they had

used a particular strategy during the tutoring were

considered. This allowed us to check whether there

was a correlation between the strategies used during

tutoring and the learning approach and personal

improvement of each student, determining which

strategies had the most significant impact by

correlating their responses with the strategies used. In

particular, we will discuss the differences greater than

1 and less than 0.61.

4 RESULTS

To answer the research questions, 553 tutors'

responses to questionnaires administered at the end of

the project were analysed.

In particular, in response to RQ1 (“What

strategies did the tutors consider effective in

improving the skills and attitudes of each student?”),

the key themes in Table 1 emerged after reading the

responses to the question: 'What aspects did you find

particularly useful and effective for the student?'. The

first column contains the keywords representing the

tutors' strategies, and the second column describes

what we attributed to them.

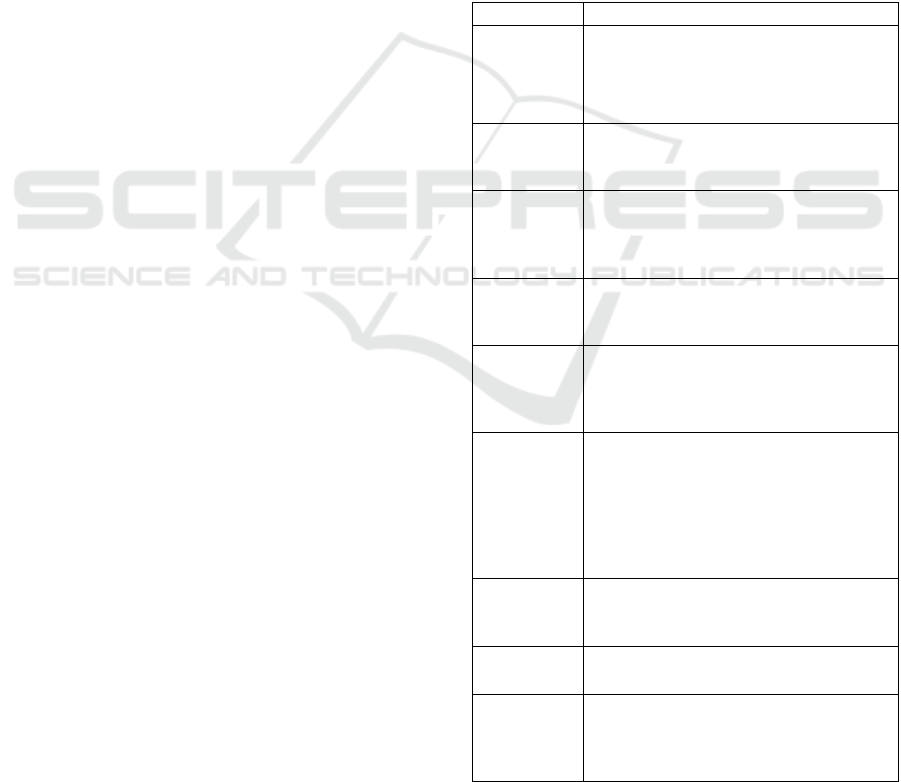

Table 1: Key terms found within the tutors' answers to the

question 'What aspects did you find particularly useful and

effective for the student?’

Keywords Description

[K1]

Support and

interaction

A set of practices, resources and dynamics

designed to facilitate student learning and

promote an effective and engaging

educational environment.

[K2]

Motivation

Reasons and incentives that motivate

students to engage in learning and

educational activities.

[K3]

Autonom

y

Support and encouragement aimed at

fostering students' responsibility for their

own learning, promoting independence and

decision-making.

[K4]

Engagemen

t

Encouragement of students’ active

participation in educational activities to

foster involvement and enthusiasm.

[K5]

Confidence

and friendship

Encouraging confidence in students'

abilities, tutors, and peers by creating a

trusting and supportive learning

environment.

[K6]

Concentration

and attention

Guiding attention, maintaining

concentration, and managing distractions to

enhance students' ability to focus their

thinking and mental energies on a specific

task for an extended period of time and

direct their senses and cognitive resources to

a specific stimulus for a short period of time.

[K7] Exercises

and Theor

y

Conceptual foundations and exercises that

enable the practical application of these

concepts.

[K8]

Interactivity

Use of information tools that 'dialogue' with

the user.

[K9]

No strategy

foun

d

Absence of effective approaches or adequate

resources to promote student learning and

participation, including lack of interest or

high levels of student absenteeism.

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

599

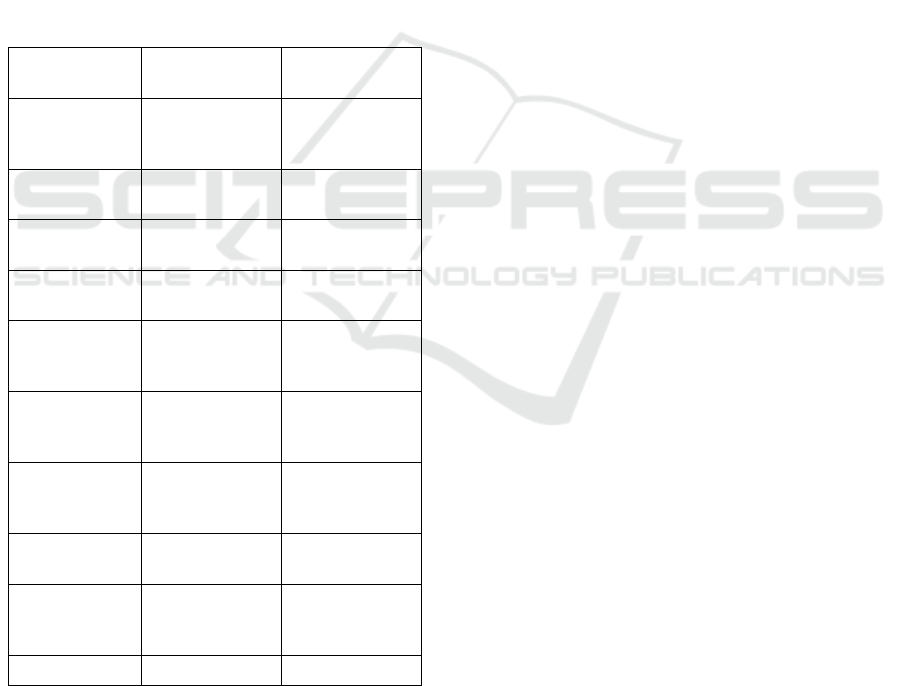

Table 2 shows the frequencies with which the key

themes were identified in the tutors’ answers. The

first column contains the keywords, the second

column shows the absolute numbers, and the third

column presents the percentages relative to the total

number of responses analysed. It is important to

clarify that the total number of responses shown in

Table 2 does not correspond to the total number of

answers to the final questionnaire since some

messages included more than one key theme. In some

cases, tutors even indicated that they used more than

one strategy in a single tutoring session. To avoid

losing relevant information and to ensure a more

complete representation of the content, it was decided

to consider each strategy separately, thus increasing

the total number of responses. This approach allows

us to reflect the variety of responses given by tutors

more accurately.

Table 2: Frequencies of key terms within the answers given

by the tutors.

Number of

answers Percent (%)

[K1]

Support and

interaction 138 18.47

[K2]

Motivation 85 11.38

[K3]

Autonom

y

23 3.08

[K4]

En

g

a

g

ement 64 8.57

[K5]

Confidence and

friendship 83 11.11

[K6]

Concentration

and attention 22 2.95

[K7]

Exercises and

Theor

y

241 32.26

[K8]

Interactivit

y

42 5.62

[K9]

No strategy

foun

d

43 5.76

Em

p

t

y

answe

r

6 0.8

The two most used strategies that emerge from the

data analysis are "exercises and theory" (K7)

(32.26%) and "support and interaction" (K1)

(18.47%). The former, representing the most used

strategy, highlights the importance of solid practical

and theoretical learning for students. The

combination of practical exercises and theory,

included under the same keyword as they were

always found together within the tutors' answers,

allows knowledge to be consolidated and helps to

overcome learning difficulties, especially in scientific

subjects such as Mathematics. It is important to

remember that the primary objective of the

compiti@casa project is to provide support to

students who need assistance in their learning through

distance tutoring. Therefore, these results align with

the project's main objective of helping students

overcome their learning challenges. Support and

interaction, on the other hand, respond to the need to

create an empathetic and motivating learning

environment. Thanks to the proximity in age between

tutors and students, the interaction is more natural and

favourable, stimulating engagement.

To answer RQ2 (“Is the impact of different

tutoring practices visible on students' learning

approach and personal improvement?”), we instead

looked at the answers to questions D1-D8, where the

tutor was asked, considering the aspect investigated

in the question, to indicate the level of each student at

the beginning and end of the project. This allowed us

to calculate each student's difference between the

beginning and end of the project and highlight

improvements.

The average difference was then calculated for

each question, taking into account only the data of

those students for whom the tutor indicated that they

had used a particular strategy during the tutoring

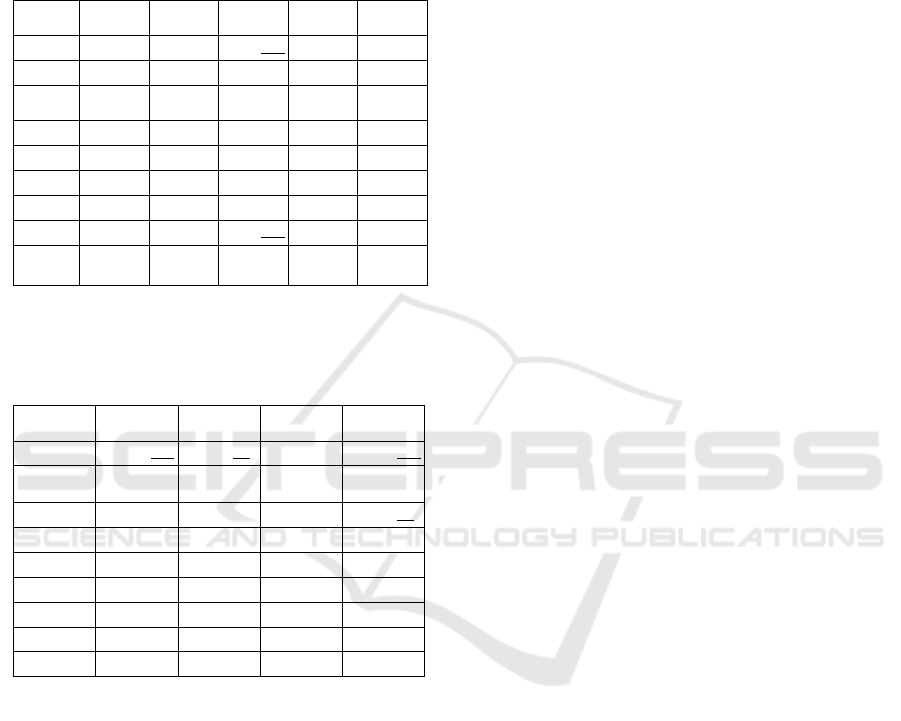

sessions. Table 3 shows the average difference of

ratings across the different aspects investigated in

questions D1-D8 in relation to the tutoring strategies

used (K1-K9). Each cell then indicates the average

difference observed in each D-aspect correlated with

a specific K-strategy. For example, we can see the

relationship between focusing tutoring on K1

(support and interaction) and aspects such as

motivation (D1), subject competence (D2), etc.

Firstly, it is interesting to observe that all the

values in Table 3 are positive, meaning that all the

aspects investigated with the D-questions improved

thanks to the project. Looking at the data in the last

row, which represents the average of the difference

between the initial data and the final data for each

keyword, we can see that the tutor strategies based on

"confidence and friendship" (K5), "motivation" (K2),

and "engagement" (K4) had the greatest effect overall

since they result in a higher growth considering

altogether the aspects investigated by questions D1-

D8 (the growths are 0.91, 0.89 and 0.79 respectively).

These results suggest that overall, acting on the

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

600

students' motivation and awareness of their abilities

significantly impacts learning attitudes.

Table 3: a) Average difference in responses to questions

D1-D8 on students' skills and attitudes according to the

tutoring strategies (K1-K5) that tutors reported using in the

compiti@casa project.

K1 K2 K3 K4 K5

D1 0.64 0.71 0.57 0.72 0.83

D2 0.72 0.84 0.7 0.86 0.92

D3 0.68 0.68 0.74 0.86 0.84

D4 0.75 0.86 0.87 0.65 0.83

D5 0.85 1.13 0.74 0.88 1.05

D6 0.83 1.04 0.65 0.88 1.01

D7 0.7 0.87 0.74 0.74 0.82

D8 0.83 1.01 0.61 0.75 0.98

Total

average 0.75 0.89 0,7 0.79 0.91

Table 3: b) Average difference in responses to questions

D1-D8 on students' skills and attitudes according to the

tutoring strategies (K6-K9) that tutors reported using in the

compiti@casa project.

K6 K7 K8 K9

D1 0.41 0.54 0.74 0.49

D2 0.77 0.75 0.79 0.68

D3 0.91 0.64 0.69 0.61

D4 0.82 0.65 0.79 0.65

D5 0.73 0.86 0.86 0.78

D6 0.82 0.81 0.71 0.75

D7 0.82 0.7 0.62 0.65

D8 0.77 0.79 0.76 0.75

Total average 0.76 0.72 0.74 0.67

In Table 3, we have highlighted the values greater

than 1 in bold, which indicate the higher growths. In

particular:

● "Motivation" (K2) and "Does the student show

confidence in his/her abilities?" (D5): this

suggests that working on motivation tends to

make students more confident in their

abilities. When students are engaged and

motivated in their learning journey, they are

more likely to recognise their progress and

feel competent (Deci et al., 1991). In the

context of compiti@casa, students receive

personalised support from tutors who guide

them through their learning process, which

boosts self-confidence and helps students feel

able to face challenges and solve problems

with greater confidence.

● “Motivation” (K2) and “Does the student have

self-esteem?” (D6): students with whom the

tutor has worked on motivation tend to

develop a positive self-evaluation, as they are

more likely to notice their successes and

recognise improvements in their skills. In the

compiti@casa project, the continuous support

from tutors and the structured approach that

helps students achieve concrete improvements

in academic subjects can contribute to

building a positive self-image, which

promotes a calm and confident learning

experience.

● “Motivation” (K2) and “Is the student aware

of his/her strengths?” (D8): students with

whom the tutor has worked on motivations

tend to be more aware of their strengths as they

are more engaged in the learning process and

focus on their achievements. With the support

of the tutors and the opportunity for regular

interaction through the DLE, students in the

compiti@casa project have the chance to

reflect on their progress and continuously

recognise and develop their skills. This

awareness strengthens their commitment and

motivates them to continue growing in both

scientific and humanistic subjects.

● “Confidence and friendship” (K5) and “Does

the student show confidence in his/her

abilities?" (D5): working on students'

confidence in their abilities is often linked to

the ability to establish positive social

relationships. Students who feel confident in

their abilities tend to be more open and interact

positively with others (e.g., Amerstorfer &

Freiin von Münster-Kistner, 2021; Gorsy &

Panwar, 2015). In compiti@casa tutoring

sessions, students work in small groups and

receive support from young tutors who are, as

mentioned, close to them in age, which creates

a more empathetic environment. This

facilitates peer interaction and the creation of

relationships, contributing to a positive

climate that further fosters everyone's

confidence in their abilities.

● “Confidence and friendship” (K5) and “Does

the student have self-esteem?” (D6): students

with whom work has been done to improve

self-esteem tend to form stronger friendships

because they are able to interact with others in

a healthy and positive way. Indeed, good self-

esteem allows students to feel more confident

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

601

in social interactions, facilitating the

formation of stronger and more lasting

friendships (see, e.g., El-Daw & Hammoud,

2015). In the compiti@casa project, the

interaction between students and tutors fosters

a supportive environment where relationships

can easily develop as each participant feels

respected and valued, which also contributes

to an improved overall learning atmosphere.

Moving on to analyse the lower values, specifically

those below or close to 0.61, underlined in Table 3,

we can observe the following relations:

● "Autonomy" (K3) and "Does the student show

motivation?" / "Autonomy" (K3) and "Is the

student aware of his/her strengths?" (D8): this

suggests that although autonomy is an

important factor in promoting awareness of

one's abilities, the effect does not seem to be

particularly pronounced. Students with greater

autonomy in learning tend to be more inclined

to reflect on their strengths and manage their

learning process. However, the results suggest

that the student's motivation might be key in

this process. Motivated students may be more

likely to develop awareness of their strengths,

even if they enjoy greater autonomy.

Additionally, students' age could affect their

ability to self-reflect. Young students may not

have fully developed an awareness of their

strengths, but students whose tutors have

worked on autonomy are more likely to

develop this awareness in the future.

Furthermore, the context of compiti@casa,

which provides constant support, may

somewhat mitigate the impact of autonomy on

self-awareness, as students may rely on their

tutors for guidance.

● “Concentration and attention” (K6) and “Does

the student show motivation?” (D1): although

working on concentration and attention is

important for motivation (see, e.g., Anggraini

& Dewi, 2022; Suparman et al., 2023), the

results suggest that they are not the only

elements influencing students' motivation

levels. Motivation may also depend on other

factors, such as personal interest in the

subjects being studied, a sense of competence,

or the environment in which the student is

placed. For example, if a student does not find

the subject interesting or useful and is not

engaged, he or she may find it difficult to

concentrate (Suparman et al., 2023; Ng et al.,

2018). In the compiti@casa project,

motivation may be influenced more by the

relationship with the tutor or the support

received than simply the ability to concentrate,

including the use of digital activities,

highlighting that motivation is multifactorial.

● “Exercises and theory” (K7) and “Does the

student show motivation?” (D1): this suggests

that working on exercises and theory does not

have a strong impact on students' motivation.

While it is true that exercises can stimulate

interest in a subject, the balance between

theory and practice does not always lead to a

significant increase in motivation. Motivation

could also be influenced by the perception of

usefulness or the degree of personal interest in

a topic. In the case of compiti@casa,

motivation may come more from the

personalised support and the opportunity to be

actively guided by the tutor and from the use

of digital activities than from the theoretical or

practical approach itself.

● "No strategy found" (K9) and "Does the

student show motivation?" (D1) / "No strategy

found (K9)" and "Does the student

demonstrate the ability to learn?" (D3): These

scores suggest that the absence of strategies

employed by the tutor to work with the student

does not appear to be strongly associated with

either motivation or learning potential. It may

be the case that students without structured

strategies employed by the tutor may still

show good motivation or learning potential.

Alternatively, it may be that the tutor was

unable to identify the proper strategy to

implement. It is also worth noting that the

answers classified in K9 are also those in

which the tutors stated that students showed

up little to tutoring sessions or whose students

participated with much disinterest (i.e., did not

interact with the tutor and peer, did not turn on

the webcam, said they had no homework or

did nothing at school). This may have led to

difficulty for the tutor in identifying and then

implementing specific strategies to foster

motivation and ability to learn. In addition, if

a student has been encouraged by family

members or teachers to participate in the

project, he or she may not develop effective

learning strategies without intrinsic

motivation. This could result in a superficial

level of engagement with limited active

participation because the initiative does not

stem from genuine personal motivation. This

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

602

type of approach, where pupils are not entirely

motivated from within, can also have a

negative impact on the quality of learning,

especially if the group dynamics or

environment does not encourage deeper

participation.

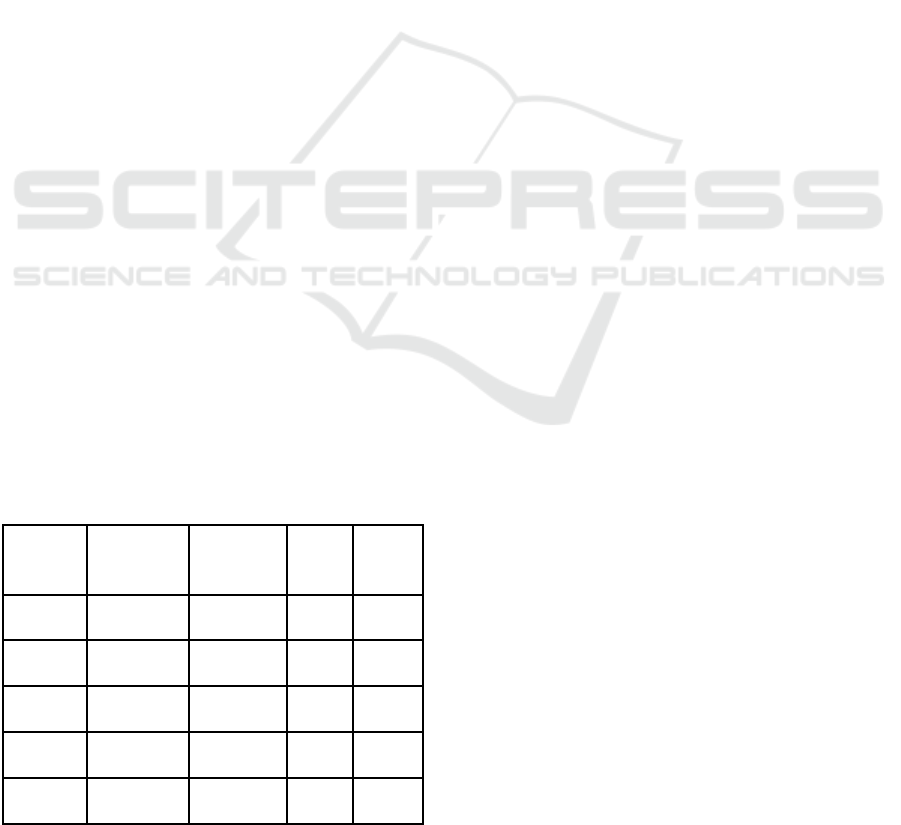

An ANOVA test was applied to explore further

the effectiveness of those tutoring strategies that have

had a greater improvement in relation to the

corresponding aspects of students' skills and attitudes

in learning (i.e., those highlighted in bold in Table 3).

We investigated if there is a statistically significant

difference in the students' skills or attitudes between

having used or not having used a certain strategy

during the tutoring sessions. We divided the answers

for each D-question into those in which a particular

K-strategy emerged and those in which it did not. We

considered the differences of the tutors’ ratings in D-

questions between the end and the beginning of the

project. We then compared the two groups. In this

way, the relationships between strategies such as

“Motivation” (K2) and “Confidence and friendship”

(K5) and specific dimensions of students'

development, including confidence in abilities (D5),

self-esteem (D6), and awareness of strengths (D8),

have been examined. The results are shown in Table

4. In particular, the first column explicates the

relation studied. The second column (“mean_n”)

shows the average of the differences between the

initial and final values for each D-question,

considering only those in which the K-strategy

studied was not used by the tutor, the third

(“mean_y") instead refers to the D-question values in

which the tutor used the K-strategy. The fourth

column shows the F-value, and the fifth shows the

respective p-value.

Table 4: Results obtained with the ANOVA test to highlight

the statistical significance of the relationships between the

strategies adopted and the improvements obtained.

mean_n mean_y F p-

value

K2 - D5 0.74 1.13 283.43 <0.001

K2 - D6 0.71 1.04 251.76 <0.001

K2 - D8 0.71 1.01 293.20 <0.001

K5 - D5 0.75 1.05 287.53 <0.001

K5 - D6 0.71 1.01 255.58 <0.001

The p-values, significantly below the conventional

threshold of α=0.05, indicate that the probability of

the observed relationships occurring by chance is

extremely low. This provides strong evidence of a

statistically significant relationship between the

tutoring strategies adopted (such as "motivation"

(K2) and "confidence and friendship" (K5)) and the

specific aspects of students' development analysed

(confidence in abilities (D5); self-esteem (D6); and

awareness of strengths (D8)). In other words, the

results confirm that the strategies implemented during

the project had a measurable and meaningful impact

on these dimensions of student improvement.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In response to the first research question (RQ1) -

What strategies did tutors consider to be effective in

improving the skills and attitudes of individual

students? -the analysis of the tutors' responses

showed that the most effective strategies were those

based on support and interaction, which aligns with

what is suggested in the existing literature. The active

involvement of students through practical activities,

such as the use of tailor-made exercises, was

considered an important aspect by tutors, even

though, as highlighted in the analysis of RQ2, such

practical activities were not always the most effective

in improving aspects like motivation. This

discrepancy may suggest that while tutors view these

activities as valuable, further reflection on their actual

impact on students' motivation is needed.

Furthermore, creating an environment of trust and

cooperation between tutors and students promoted the

development of interpersonal skills and increased

students' self-esteem, confirming the findings of

previous studies such as those by Pasion (2024) and

Gortazar et al. (2024), which had already highlighted

the effectiveness of tutoring in improving academic

and social performance.

Concerning the second research question (RQ2) -

Is the impact of different tutoring practices visible on

students' learning approach and personal

improvement? - the data collected show a significant

improvement in "motivation" and "confidence and

friendship", particularly for those who were more

actively engaged in an interactive and personalised

approach. Analysis of the average difference between

the final and initial answers according to the tutoring

strategies used by the tutors revealed that

"motivation" (K2) and "confidence and friendship"

(K5) were particularly prominent. Furthermore, when

analysing the relationship between each question

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

603

according to the tutoring strategies, 'Does the student

show confidence in his/her abilities?' (D5) and 'Does

the student have self-esteem?' (D6) emerged

significantly. This is in line with metacognitive

theories that emphasise the importance of reflection

and monitoring one's own learning processes

(Hrbáčková et al., 2012). However, in some cases, the

effectiveness of tutoring practices was limited by the

lack of active student participation, especially when

lack of motivation or high absenteeism hindered

progress. This confirms the importance of more

personalised approaches, as suggested by Hossein-

Mohand and Hossein-Mohand (2023), to address the

specific needs of struggling students. The statistical

significance of the results, supported by the ANOVA

test, further validates the positive impact of strategies

such as “motivation” (K2) and “confidence and

friendship” (K5) on key dimensions of students'

personal growth, including confidence (D5), self-

esteem (D6), and awareness of strengths (D8). In

conclusion, the results of this study confirm that

tutoring is an effective tool for improving learning

skills and students' attitudes and self-esteem. These

results align with studies such as (Gortazar et al.,

2024), which demonstrate the potential of well-

designed tutoring programs to produce both cognitive

and emotional benefits. Additionally, the project's

emphasis on relational aspects between tutors and

students reflects findings from interventions like the

Fuoriclasse project (Ambrosini & De Simone, 2015),

which helped reduce dropout rates by integrating

motivational and relational components into its

educational strategies. However, there is still room

for improvement, particularly in terms of adapting

tutoring methods to better engage less motivated

students or those with attendance difficulties. Future

studies could explore new ways of making these

strategies more flexible and effective, adapting them

to the different needs of students and thus maximising

the benefits both in terms of learning and personal.

One potential avenue is the exploration of advanced

technologies, such as artificial intelligence, to further

personalise the tutoring experience and provide real-

time adaptive feedback.

Despite the positive results, the study has some

limitations that need to be highlighted. Firstly, the

sample analysed includes a limited number of

students and tutors belonging to a specific context,

which may reduce the generalisability of the results

to other educational contexts. Secondly, the data

collected are mainly based on tutors' perceptions, a

methodology that, although useful for exploratory

analysis, may introduce a subjective bias. Integration

with more objective measures, such as school results

or direct observation, could provide a more complete

picture of the impact of tutoring.

To overcome these limitations, future research

could explore the effectiveness of tutoring in more

diverse contexts and larger samples, including more

instruments and viewpoints.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Fondazione De Agostini, IGT, Fondazione

Alberto e Franca Riva, and Fondazione Comunità

Novarese, which made it possible to repeat the project

in the 2023/2024 school year. We would also like to

thank the school principals and teachers who

collaborated to develop the project.

Part of the research of this publication is

supported by a grant under the National Recovery and

Resilience Plan (NRRP), D.M. 118/2023 by the

Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR),

funded by the European Union–NextGenerationEU.

REFERENCES

Acharya, B. R. (2017). Factors affecting difficulties in

learning mathematics by mathematics learners.

International Journal of Elementary Education, 6(2), 8-

15.

Ambrosini, M. T., & De Simone, G. (2015). Fuoriclasse: Un

modello di successo per il contrasto alla dispersione

scolastica. Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli - Save The

Children. https://www.savethechildren.it/cosa-

facciamo/pubblicazioni/fuoriclasse-un-modello-di-

successo-il-contrasto-alla-dispersione

Amerstorfer, C. M., & Freiin von Münster-Kistner, C.

(2021). Student perceptions of academic engagement

and student-teacher relationships in problem-based

learning. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 713057.

Anggraini, S., & Dewi, S. K. (2022). Effect of Brain Gym in

Increasing the Learning Concentration of 6th Grade on

Online Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 18.

Balbo, A., Barana, A., Boetti, G., Conte, M. M., & Omegna,

S. (2024). Digital Technologies and Their Impact on

Metacognitive Aspects in Learning Recovery in

Scientific and Humanistic Subjects. Proceedings of the

18th International Conferences on e-Learning and

Digital Learning 2024, ELDL 2024, 105–112.

Barana, A., Boffo, S., Gagliardi, F., Garuti, R., & Marchisio,

M. (2020a). Empowering Engagement in a Technology-

Enhanced Learning Environment. In M. Rehm, J.

Saldien, & S. Manca (A c. Di), Project and Design

Literacy as Cornerstones of Smart Education (Vol. 158,

pp. 75–77). Springer.

Barana, A., Brancaccio, A., Conte, A., Fissore, C., Floris, F.,

Marchisio, M., & Pardini, C. (2019a). The Role of an

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

604

Advanced Computing Environment in Teaching and

Learning Mathematics through Problem Posing and

Solving. Proceedings of the 15th International Scientific

Conference eLearning and Software for Education, 2,

11–18.

Barana, A., Marchisio, M. and Miori, R. (2019b). MATE-

BOOSTER: Design of an e-Learning Course to Boost

Mathematical Competence, Proceedings of the 11th

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU 2019), 280–291.

Barana, A., Casasso, F., Fissore, C., Marchisio, M., &

Roman, F. (2021). Mathematics Education in Lower

Secondary School: Four Open Online Courses to

Support Teaching and Learning. Proceedings of the 18th

International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory

Learning in Digital Age CELDA2021, 95-102.

Barana, A., Fioravera, M., Marchisio, M., & Rabellino, S.

(2017). Adaptive Teaching Supported by ICTs to

Reduce the School Failure in the Project “Scuola Dei

Compiti”. Proceedings of 2017 IEEE 41st Annual

Computer Software and Applications Conference

(COMPSAC), pp. 432–437.

Barana, A., Fissore, C., & Marchisio, M. (2020b). From

Standardised Assessment to Automatic Formative

Assessment for Adaptive Teaching. Proceedings of the

12th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education, 285–296.

Barana, A., & Marchisio, M. (2022). A model for the

analysis of the interactions in a digital learning

environment during mathematical activities. In

International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (pp. 429-448). Cham: Springer International

Publishing.

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., & Rabellino, S. (2019c).

Empowering Engagement through Automatic

Formative Assessment. 2019 IEEE 43rd Annual

Computer Software and Applications Conference

(COMPSAC), 216–225.

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M.

(1991). Motivation and education: The self-

determination perspective. Educational psychologist,

26(3-4), 325-346

Dietrichson, J., Bøg, M., Filges, T., & Klint Jørgensen, A.

M. (2017). Academic interventions for elementary and

middle school students with low socioeconomic status:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. Review of

educational research, 87(2), 243-282.

El-Daw, B., & Hammoud, H. (2015). The effect of building

up self-esteem training on students’ social and academic

skills 2014. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,

190, 146-155.

Fagnani, G., & Scanu, P. (2020). Emergenza scuola: I

bisogni ignorati dei nostri figli nella crisi sanitaria. Il

Leone Verde Edizioni.

Giraudo, M.T., Marchisio, M. and Pardini, C. (2014).

Tutoring with new technologies to reduce the school

failure and promote learning of mathematics in

secondary school, Mondo Digitale, 13(51), 834–843

Gorsy, C., & Panwar, N. (2015). Study of self-confidence as

a correlate of peer-relationship among adolescents.

International Journal of Education &Management

Studies, 5(4), 298-301.

Gortazar, L., Hupkau, C., & Roldán-Monés, A. (2024).

Online tutoring works: Experimental evidence from a

program with vulnerable children. Journal of Public

Economics, 232, 105082.

Hossein-Mohand, H., & Hossein-Mohand, H. (2023).

Influence of motivation on the perception of

mathematics by secondary school students. Frontiers in

Psychology, 13, 1111600

Hrbáčková, K., Hladík, J., & Vávrová, S. (2012). The

relationship between locus of control, metacognition,

and academic success. Procedia-Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 69, 1805-1811.

INVALSI. (2021). Le diseguaglianze che non si vedono

senza dati per tutti [online]. INVALSIopen.

OCSE PISA. (2022). I risultati degli studenti italiani in

matematica, lettura e scienze

Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito (2022). Azioni di

prevenzione e contrasto della dispersione scolastica

[online]. Futura PNRR.

Moscoviz, L., & Evans, D. K. (2022). Learning loss and

student dropouts during the covid-19 pandemic: A

review of the evidence two years after schools shut

down.

Morabito C. (2022). Povertà educativa: necessario un

cambio di passo nelle politiche di contrasto. Save The

Children Italia. https://s3-

www.savethechildren.it/public/files/Poverta_educativa.

pdf

Ng, C., Bartlett, B., & Elliott, S. N. (2018). Empowering

engagement: Creating learning opportunities for

students from challenging backgrounds. Springer.

PASION JR, O. V. (2024). Benefits of Peer Tutoring in

Enhancing Students’ Academic Performance in

Mathematics.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic

motivations: Classic definitions and new directions.

Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 54-67.

Suparman, T., Anggraeni, S. W., Nurjanah, T., &

Cahyaningsih, U. (2023). THE INFLUENCE OF

LEARNING MOTIVATION AND LEARNING

CONCENTRATION ON UNDERSTANDING OF

MATHEMATICS CONCEPTS. Jurnal Cakrawala

Pendas, 9(1), 153-163.

Szabó, C. M. (2018). Causes of early school leaving in

secondary education. Journal of Applied Technical and

Educational Sciences, 8(4), 54-76.

Topping, K. (2000). Tutoring. Educational Practices Series-

-5.

Unicef. (2021). The state of the global education crisis: a

path to recovery: a joint UNESCO, UNICEF and

WORLD BANK report. Paris: UNESCO, cop. 2021.

Wilson, B. G. (1995). Metaphors for instruction: Why we

talk about learning environments. Educational

Technology, 35(5), 25-30.

Zhang, L., Pan, M., Yu, S., Chen, L., & Zhang, J. (2021).

Evaluation of a student-centered online one-to-one

tutoring system. Interactive Learning Environments,

31(7), 4251-4269.

The Effectiveness of Tutor Strategies in Enhancing Students’ Learning and Attitudes in Scientific and Humanistic Subjects: An Analysis of

Tutor Strategies Within the Compiti@Casa Project

605