Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social

Skills Development

Nada Sharaf

Faculty of Informatics and Computer Science, The German International University, Egypt

Keywords:

Virtual Reality, Autism, Collaborative Tools, Social Skills.

Abstract:

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) require new interventions because social communication can be specially

challenging. Such interventions could help social skills grow. Collaborative virtual reality (VR) technology

enables having different interactive and engaging environments. It offers a promising ways for improving

many skills since people can safely engage with others as well as learn with others. This paper reviews the

application of collaborative VR in improving social skills among children with ASD. The reviews shows the

potential of collaborative VR to simulate deeply dynamic social interactions in a carefully controlled setting

as well. Different studies show that collaborative VR use can help children with ASD improve empathy, social

understanding, and teamwork. However, there are still some difficulties including accessibility as well as

the possible need for individualized interventions and potential sensory overload. This review points out the

opportunities that collaborative VR provides for meaningful learning improvements and for the large practice

of social interactions in an engaging way. It also discusses the actual obstacles,that need to be addressed, to

completely maximize the advantages of VR technologies regarding social skills development in ASD. The

provided analysis could help support innovation and research in the field.

1 INTRODUCTION

One important challenge for individuals with autism

is that they often battle with communication and so-

cial skills. Autistic children often have major prob-

lems relating to others, and these problems can show

up in many social situations. Frequently, these chil-

dren battle with understanding facial expressions or

with reacting suitably to other people’s emotional

suffering which are key parts of human interaction

(Garfin and Lord, 1986). Difficulties also affect mul-

tiple nonverbal communication skills, such as gaze

communication, which is important for performing

all social interactions and developing all relationships

(Weiss and Harris, 2001). Specific communication

difficulties truly highlight how the social challenges

encountered by people with autism are exceptionally

complex and quite multidimensional, thus stressing

the necessary need for carefully tailored interventions

that directly address these particular areas of concern.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has a wide-

ranging array of conditions, stretching from low-

functioning autism (LFASD) to high-functioning

autism (HFASD) alike (Ahmad Basri et al., 2024).

The spectrum thoroughly reflects the multiple abili-

ties displayed by many people diagnosed with ASD

emplasizing the challenges they face and the need

for therapeutic approaches that address their specific

needs.

In recent years, Virtual Reality (VR) has evolved

as a tool with great potential for intervention in ASD.

VR technology is engaging and highly enjoyable. It is

thus recognized for its ability to substantially improve

social skills among people with ASD. These particu-

lar VR aspects thoroughly catch the interest of ASD

users, and motivate them to engage with therapeutic

activities that are carefully designed to improve so-

cial interactions as well as communication skills (Ah-

mad Basri et al., 2024; Mosher and Carreon, 2021).

This approach uses all of the engaging and interac-

tive features of VR to make controlled environments

where many people with ASD can safely practice and

learn social skills.

Well-designed serious games are cost-effective

and effective educational tools for all the different

needs of autistic children. They could be tailored to

meet their specific needs as well (Noor et al., 2012).

Different plaforms have been intoridced for different

purposes (Elshahawy et al., 2020a; Elshahawy et al.,

2020b; Elshahawy et al., 2022). Since these games

590

Sharaf, N.

Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social Skills Development.

DOI: 10.5220/0013437400003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 590-597

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

can be used across many homes, classrooms, or ther-

apeutic settings, they offer a meaningful supplement

to established educational approaches. Through the

careful incorporation of elements that accommodate

the special sensory and cognitive preferences of autis-

tic learners, serious games are able to provide a more

fitting learning experience. They help to maintain a

certain level of focus and reduce anxiety through very

structured and predictable interactions which autistic

children often find reassuring (Ke and Moon, 2018).

Serious games make learning more flexible and less

overwhelming because the controlled environment al-

lows adjustments to sensory inputs and interaction

complexity. This tailored approach strengthens the

development of many social skills and communica-

tion skills in a way that respects all of the special chal-

lenges autistic children face and thus improving every

educational outcome.

Collaborative environments, since they are es-

pecially useful for teaching communication, could

be outstanding training simulations for children with

autism. These environments can be changed across

many settings to improve a variety of skills. Collab-

orative virtual learning has an advantage over single-

user 3D environments; it can meet all learning needs

involving social interaction. This approach helps

build important skills. Also, it uses the advantages of

social learning to encourage and improve the learning

experience (Wang et al., 2017). These environments

can effectively tackle the special challenges and learn-

ing styles of autistic children by promoting highly in-

teractive and exceptionally cooperative learning sce-

narios, which provides them with the tools needed to

succeed socially.

There is no much of empirical evidence that cur-

rently supports the effectiveness of Virtual Environ-

ments (VEs) as a teaching tool for all individuals

with autism (Mitchell et al., 2007). However, there

are strong hints of potentially large benefits appear in

some studies. As an instance, the study presented in

(Strickland, 1996) carefully observed that two partic-

ularly low-functioning children with autism could ap-

propriately track events in a thoroughly engaging VE

by using orienting movements. Additionally, (Parsons

et al., 2004) reported that all teenagers with Autism

Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) could fully navigate and

function in a virtual cafe environment presented on a

desktop. Such findings support the fact that VEs may

be a true potential to act as a therapeutic instrument

for improving certain cognitive as well as social skills

in individuals with autism.

CVEs allow users to communicate and engage

within a shared virtual space. Within a typical vir-

tual environment, users are presented a precisely

computer-generated simulation of a particular scene

or world. In addition, they can thoroughly explore it,

and fully interact with it (Millen et al., 2011). This

setup facilitates individual exploration. It also makes

collaborative experiences better, allowing all partici-

pants to do activities together in a simulated setting.

This paper seeks to explore the teaching of so-

cial skills to autistic children by using Virtual Reality

(VR) settings that have collaborative environments.

These interactive VR platforms explore the ways in

which they ease each learning type as well as improve

each social competency through allowing all children

to fully engage in every simulated social interaction.

The paper gives perceptive recommendations for us-

ing VR in autism education. The recommendations

are deeply informed by many studies and offer a more

thorough look into effective practices and strategies.

2 INTERACTIONS IN CVEs

The study (Schroeder et al., 2006) thoroughly inves-

tigated each aspect of the design usability of 3D Col-

laborative Virtual Environments (CVEs). This in-

cluded using analytical methods from different re-

search efforts created to fully understand interaction

dynamics within those digital settings. The initial

study involved a strict quantitative analysis of action

sequences. Every observable behavior was systemat-

ically categorized into eight fundamental categories:

communicate (C), external (E; relating to events out-

side the virtual environment), gesture (G), manipulate

(M), navigate (N), position (P), scan (S), along with

verify (V). This approach, which was highly struc-

tured, not only cataloged behaviors but also clarified

how participants either followed or strayed from so-

cial standards during interactions. Initially, most in-

teractions appeared to focus on the looks and social

customs of avatars. However, all interactions gradu-

ally shifted to more helpful communication about def-

inite tasks, so many avatars were viewed as functional

parts of the collaboration.

A qualitative approach was carefully used for the

second analytical method. All transcripts of every

verbal communication were examined throughout the

CVE’s different collaborative activities. This analysis

carefully spotlighted the undeniably large roles that

verbal and also non-verbal cues played within collab-

orative dynamics. It was thorough and detailed. It

also gave plentiful understandings of the content as

well as of the subtle details of social interactions. Po-

sitioning, navigation, gesturing, and object manipu-

lation, each action in the virtual space, greatly eased

communication and collaboration when executing the

Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social Skills Development

591

task, having a large influence. These findings, with

support from more research from (Steed et al., 2003),

pointed out that social interactions in virtual places

are not simple, in addition to giving detailed views

of the participants interact with the virtual space as

well as each other. (Tromp et al., 2003) employed

statistical techniques. Such techniques analyze the

frequency and sequence of the interactions noted, of-

fering a more thorough overview of participant per-

formance and collaborative behavior in CVEs. These

studies offer a thorough and multi-dimensional view

of all the ways that CVEs can support and also im-

prove collaborative experiences, presenting large un-

derstandings for the effective design and implementa-

tion of virtual spaces for collaboration.

3 AUTISM AND SOCIAL

TRAINING IN CVEs

Social skills are key focus areas for virtual reality

training in autistic people (Ahmad Basri et al., 2024),

especially assessing non-verbal responses, starting

and keeping up conversations, and also managing

emotional challenges with care. Within this frame-

work, Collaborative Virtual Environments (CVEs) are

exceptionally promising, particularly for greatly im-

proving the social skills of autistic children through

the utilization of absorbing virtual reality tools.

It was noted that interventions that promote role-

play can offer large benefits to collaborative inter-

actions inside CVEs (Parsons and Mitchell, 2002).

Role-play encourages mental simulation, in addition

to giving users chances to explore social standards

in a secure setting. Because CVEs have the ability

to mimic countless real-world interactions, users are

able to experiment with and understand multiple so-

cial behaviors and cues without fearing any repercus-

sions in the real world.

3D CVEs provide autistic youth with many ben-

efits. Learners are able to take part in real social

situations and realistic role-playing in a simulated

space that is controlled with care in these environ-

ments. This learning method helps autistic children

build social skills without frustrating peers or teachers

and without risking negative consequences in the real

world (Standen and Brown, 2006; Wang et al., 2017).

These settings provide large advantages, particularly

as they enable wide-ranging practice and steady learn-

ing of all specific social skills, which are commonly

challenging for autistic learners.

The review provided in (Khatab et al., 2024) also

stresses the important role that collaborative play has.

Collaborative play improves communication skills for

autistic children. Working towards shared goals in

a CVE allows each autistic child to interact with

each neurotypical peer under the total guidance and

support of mediators, like parents or teachers, be-

cause it promotes multiple social skills and guaran-

tees complete inclusivity. Integrating technology via

an all-embracing environment effectively strengthens

a number of social developments, as it gives each

autistic child tools to navigate social interactions with

added confidence as well as success.

There exists a lack of investigations exploring

how evidence-based strategies, importantly cognitive

as well as behavioral techniques, are integrated ef-

fectively into Virtual Reality (VR) environments for

teaching social skills to each of the people with high-

functioning autism spectrum disorder (HFASD) (Ah-

mad Basri et al., 2024). This gap strongly stresses the

need for a more deep investigation into the method-

ologies used to change these therapeutic techniques

for VR settings, also pointing out how this medium

possesses important potential for both engaging and

effective intervention.

The review provided (Thai and Nathan-Roberts,

2018) pointed out that VR interventions target social

skills with large variability, stressing that there is no

agreement on the most important skills to address in

these settings. According to this finding, the field may

still be exploring the best ways to use VR for social

skills training. Mesa-Gresa et al. (Mesa-Gresa et al.,

2018) encountered a wide range of social skills targets

across the reviewed articles. This further indicates the

diverse approaches and potential breadth of VR appli-

cations in social skills training.

Furthermore, as shown in (Millen et al., 2011;

Cobb et al., 2002) Collaborative Virtual Environ-

ments (CVEs) and Shared Active Surfaces (SASs)

are very effective when it comes to improving so-

cial skills and promoting collaborative interactions

among children with HFASD. These findings suggest

that CVEs can be used by autistic children as a dy-

namic platform that offers a supportive, highly engag-

ing, and interactive place to learn and practice social

skills. CVEs let these children safely explore and re-

hearse social interactions through peer interaction in

a controlled setting, which is important for social de-

velopment.

It is important to continue exploring and improv-

ing all CVEs as tools to help build social skills. To

assist a number of HFASD people, investigation into

how collaborative settings in CVEs can be greatly op-

timized to support exact educational and therapeutic

outcomes is important. This exploration is quite im-

portant, for it has the potential to lead to fully tai-

lored as well as highly impactful interventions deal-

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

592

ing with all the special needs of this population. Their

ability to function socially along with emotionally in

all wider community settings should greatly improve.

This research importantly adds to both the academic

and practical comprehension of VR and CVE appli-

cations, and it greatly affects the lives of people with

HFASD by giving them important skills to better han-

dle social challenges.

Virtual Reality (VR) content, according to (Par-

sons and Mitchell, 2002), could be carefully made

to connect user-centered designs to proven strategies

by including both cognitive and behavioral learning

methods. Considering cognitive along with behav-

ioral techniques have displayed effectiveness in many

customary social skills training settings (Laugeson

and Park, 2014), this integration is quite meaning-

ful. These techniques have proven successful in phys-

ical environments. How they can be changed and

used in virtual reality settings, however, is still not

well-researched. This gap is evidenced by several re-

views and research summaries (Mosher and Carreon,

2021; Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018; Thai and Nathan-

Roberts, 2018; Glaser and Schmidt, 2022; Parsons

and Mitchell, 2002), and it is pointed out by a lack of

thorough studies exploring the instantiation of multi-

ple cognitive and behavioral strategies in VR.

It is important to find out which thinking and be-

havior methods are most effective in VR and how to

smoothly incorporate them into VR social skills train-

ing, as pointed out by the limited research. Effec-

tive strategies, identified and precisely implemented

within VR, could importantly improve the engage-

ment and effectiveness of the training while furnish-

ing users with more specially personalized and flexi-

ble learning experiences. Therefore, some expansion

of this research area is absolutely necessary to ad-

vance VR as a truly influential tool in educational and

therapeutic contexts, particularly about the design of

VR content that can affect the development of social

competencies in multiple populations in an important

manner.

4 EXPLORING STUDIES ON

VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTS

FOR SOCIAL SKILLS

TRAINING

Collaborative Virtual Educational settings (CVLEs)

and Virtual Environments (VEs) have shown great po-

tential for dealing with the social difficulties expe-

rienced by people with Autism Spectrum Disorders

(ASD). This section looks at multiple studies that in-

vestigate multiple new methods for teaching social

skills through technologies that allow people to col-

laborate and participate.

The iSocial program (Wang et al., 2017) is one

example. It implemented the SCI-A curriculum into

a 3D CVLE. This program helps all youth aged 11 to

14 practice social and behavioral skills within a safe,

controlled virtual environment; it stresses many struc-

tured, engaging interactions.

Millen et al. (Millen et al., 2011) presented both

Block Party and TalkAbout, a pair of CVE applica-

tions that are intended to encourage many social con-

versation skills and collaborative strategies. Many in-

teractive tabletop experiences are also supported by

Shared Active Surface (SAS) applications, showing a

degree of adaptability and engagement of these tools

in social skills training.

The work presented in (Mitchell et al., 2007) stud-

ied the use of a caf

´

e VE by six adolescents with ASD,

who were 11 to 16 years old. In an ordinary caf

´

e set-

ting, the study found truly important improvements

in social reasoning and judgment, particularly about

seating choices. The large potential of fully engaging

VEs to effectively improve social decision-making in

adolescents with ASD is truly pointed out here.

The work introduced in (Ke and Moon, 2018) de-

veloped one complete, 3D virtual playground by way

of OpenSimulator specifically for all high-functioning

autistic (HFA) children between the ages of 10 and

14. The study indicated that VR-based gameplay im-

proved social interaction skills along with negotia-

tion, initiation, as well as response behaviors. The

results also pointed out the importance of changing

gameplay. This is based on the specific requirements

and also the skills of students.

I-interact (Elgarf et al., 2017) works on the eye

contact of children who have trouble socializing to

help them. The study used a VR serious game that had

a three-level structure. Following several sessions,

eye contact skills improved in participants aged 8 to

15, particularly when tasks were presented gradually

as well as in an engaging way. The study also stressed

that gamification and user-centered design can grow

engagement.

As the studies introduced indicate, autistic chil-

dren can collaborate in Collaborative Virtual Envi-

ronments (CVEs). This provides an especially struc-

tured and completely supportive place for develop-

ing a wide range of important social skills, includ-

ing communication, teamwork, and emotional regula-

tion. Feeling safe as well as excited, children in CVEs

watch then copy good social actions from others; this

helps them learn from each other. This approach helps

autistic children improve how they interact with oth-

Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social Skills Development

593

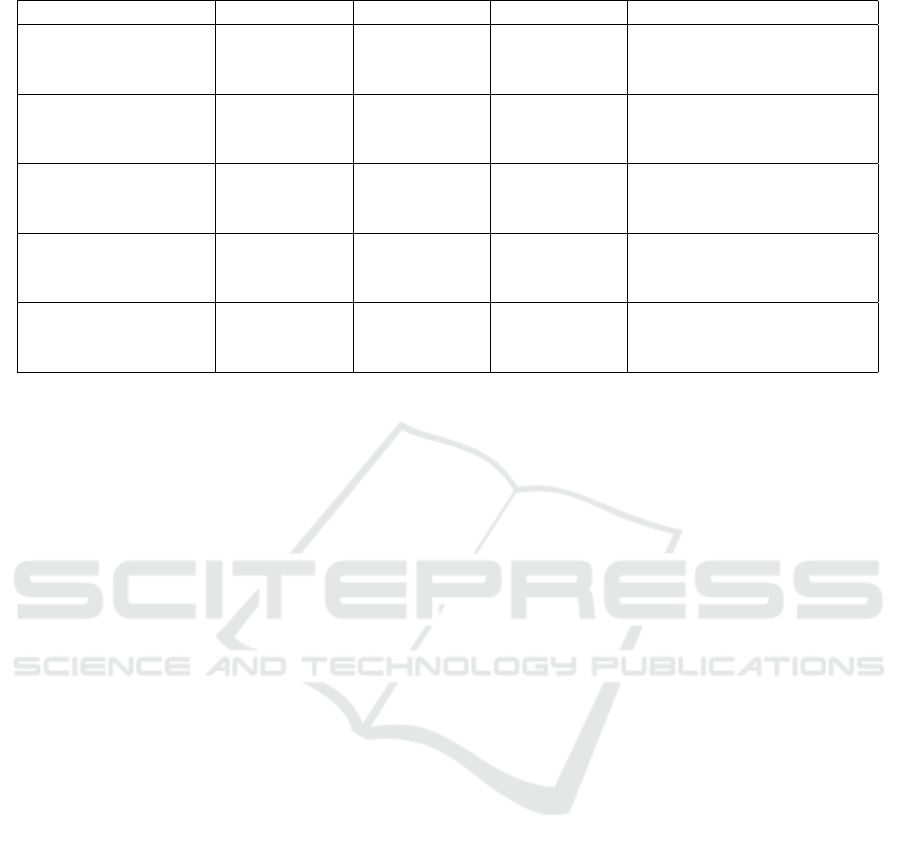

Table 1: Comparison of some of the studies on Virtual Environments for Social Skills Training.

Study Sample Size Age Range Focus Key Findings

(Wang et al., 2017) 11 11-14 iSocial (3D

CVLE)

Improved social and behav-

ioral outcomes via struc-

tured, immersive practice.

(Millen et al., 2011) Not specified Not specified Block Party,

TalkAbout,

SAS

Enhanced collaborative

strategies and social conver-

sation skills.

(Mitchell et al., 2007) 6 11-16 Caf

´

e VE Improved judgments and so-

cially relevant reasoning in

seating choices.

(Ke and Moon, 2018) 8 10-14 3D Virtual

Playground

Enhanced negotiation, initi-

ation, and response behav-

iors.

(Elgarf et al., 2017) 8 8-15 I-interact VR

Game

Improved eye contact

through gamified training of

dyadic and triadic gaze.

ers. It gives them a safe space without pressure. This

also helps lessen common problems, like social anxi-

ety and sensory overload.

Studies show collaborative tasks in CVEs have a

large effect. For example, Block Party and TalkA-

bout (Millen et al., 2011) encouraged communica-

tion skills and teamwork through multiple exercises

that involved building rapport, taking turns, and com-

municating frequently. The iSocial program (Wang

et al., 2017) also gave children goal-oriented assign-

ments that improved decision-making and collabora-

tion skills through social scenarios similar to those

in the real world. According to Ke et al. (Ke and

Moon, 2018), team-based gameplay in a 3D vir-

tual playground improved multiple social interaction

skills in addition to several negotiation, initiation, and

response behaviors.

CVEs offer customization and adaptability. This

makes sure that challenges and tasks match every par-

ticipant’s skill levels. This adaptability truly promotes

meaningful engagement along with helping to com-

pletely avoid activities that are either excessively hard

or excessively simple. The presence of neurotypi-

cal peers introduce many social models, and inter-

actions are thoroughly promoted thus improving the

collaborative environment. This dynamic encourages

a certain degree of empathy along with a definite level

of understanding among all neurotypical participants.

CVEs are an effective collaboration tool for autis-

tic people, since these people often face many social

challenges because of certain attributes.

5 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

DESIGNING VR

COLLABORATIVE

ENVIRONMENTS

Based on the different case studieson collaborative

virtual educational settings (CVLEs), the following

recommendations are proposed to carefully guide the

future design and implementation of VR collabora-

tive environments. These recommendations stress the

clear capabilities of CVEs as they address every spe-

cific need of autistic children. CVEs also teach mul-

tiple social skills.

1. Incorporate pedagogical design features: CVLEs

should be designed with a goal-oriented approach

embedding engaging stories and particular aspects

of games or role-play. Goal-oriented activities

provide important structure as well as purpose for

autistic learners. In addition, these learners of-

ten excel in extremely predictable environments.

Learners can build social skills and rehearse with-

out fear of negative real-world results because

role-play and narratives help simulate real-world

situations in a safe, controlled, virtual area (Wang

et al., 2017). Since CVEs feature collaboration,

autistic children are always able to interact with

peers in a manner similar to interactions in real

life. They are always able to repeat scenarios as

needed to fully master them. This iterative learn-

ing approach encourages communication and in-

teraction skills more.

2. Adopt a user-centered design approach: A user-

centered design guarantees CVEs completely fit

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

594

all needs of autistic children, their instructors, and

also their parents, when appropriate. This indi-

cates surroundings that are visually comfortable

as well as minimal sensory overload, along with

complete adaptability to each individual prefer-

ence, for all children. This should also include in-

terfaces that let instructors and parents easily keep

track of multiple interactions. Learning objectives

are thus met quite effectively. This approach holds

large importance within CVEs. Virtual environ-

ments can be widely customized to more effec-

tively address all specific challenges that autistic

learners face, such as difficulty with eye contact

or interpreting non-verbal cues.

3. Ensure environmental comfort and adaptability:

CVEs settings should be intensely customized

to comfortably fit personal preferences, like the

lights as well as the precise arrangement, along

with the exact height of objects. These changes

are very important for the participation of autistic

children and their well-being. Introducing chal-

lenges incrementally allows a gradual buildup of

skills [(Wang et al., 2017). Learners do not thus

experience overwhelming feelings. It is often

much harder to make adjustments in physical set-

tings and we should thus make use of this unique

feature of virtual environments.

4. Make systems adaptive: Adaptive systems are

necessary throughout CVEs to address the differ-

ent needs autistic learners. Such systems could

for example change how hard a task is, how

quickly people interact, and what kind of feed-

back is given. The learning needs of all autis-

tic children often appear highly individualized

(Wang et al., 2017). This flexibility ensures that

each child gets support made just for them. This

is also very important for teaching social skills.

Adaptive systems in CVEs permit modifications

at all times, thus supplying prompt responses to

all user behaviors along with greater participa-

tion and many educational outcomes. Adaptabil-

ity within virtual environments is important, ac-

cording to (Ke and Moon, 2018), since gameplay

made for each High-Functioning Autistic (HFA)

child raised overall engagement and also some so-

cial skills such as negotiation and initiation. To be

more effective, this finding supports the recom-

mendation that teachers customize learning sce-

narios in CVEs, allowing adjustments to tasks and

settings that accommodate each child’s skills and

preferences.

5. Include Neurotypical Peers: As discussed earlier,

integrating neurotypical children within CVEs en-

courages inclusive learning and provides autis-

tic children important opportunities to carefully

observe typical soicial behaviors. Collaborative

tasks with neurotypical peers can build multiple

teamwork skills, diverse communication styles,

and empathy (Khatab et al., 2024). The collab-

orative settings of CVEs helps with positive so-

cial interactions and decreases anxiety in autistic

children by giving them a safe space for interac-

tions with neurotypical peers, when compared to

actual settings. In collaborative places, autistic

children can watch and copy social actions. This

helps them learn from others, which is very use-

ful for those who battle with unplanned situations.

Joint activities in virtual environments, as demon-

strated by (Millen et al., 2011) with Block Party

and TalkAbout, improved conversational skills by

encouraging rapport and allowing all participants

to practice initiating and sustaining dialogue.

6. Customize learning scenarios: Customizable sce-

narios in CVEs allow educators to considerately

tailor activities to the specific needs and also the

individual goals of each learner. For instance,

scenarios can be designed to focus on initiat-

ing conversations, practicing turn-taking, or re-

sponding to non-verbal cues (Khatab et al., 2024).

This special flexibility of virtual environments al-

lows for the creation of many diverse social skill-

building activities. A collection of such activities

are needed but hard to in every customary class-

room setting.

7. Standardize evaluation methodologies: To check

and evaluate the effectiveness of CVEs inter-

ventions based, stable and standard evaluation

methodologies are cruical. Standardization guar-

antees a dependable comparison of outcomes

across many studies and settings.

8. Conduct extended follow-up sessions: Extended

follow-up sessions over extended periods are al-

ways important to make sure all the long-lasting

effects are captured. This is particularly impor-

tant for children with Autism since sometimes the

sample of children is not big. Thus, we need a

more thorough in-depth analysis of the effects.

These sessions can help determine if skills from

the virtual setting transfer to real interactions to

recognize areas that need more support. CVEs

can replicate actual situations many times, which

makes follow-up sessions very helpful. Learners

can review and also strengthen skills previously

learned over a period of time as well.

By integrating the proposed recommendations, we

hope that every future CVE system would precisely fit

all special needs of children with autism. This would

Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social Skills Development

595

definitely yield social skills training that is effective

and highly engaging. It would also be thoroughly

personalized. The collaborative and flexible nature of

CVEs provide a platform to help strengthen the so-

cial competence of users. This would help learners

achieve good milestones.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper looked into how Collaborative Virtual En-

vironments (CVEs) could change how autistic chil-

dren are taught social skills. CVEs offer remarkably

collaborative, exceptionally customizable, along with

specially engaging platforms as they handle impor-

tant challenges present in common social skills train-

ing. The reviewed studies show that they work well to

help negotiation skills, initiation skills, and also con-

versational abilities. User-centered customization and

goal-oriented tasks became a few design principles

to improve engagement and learning outcomes. Peer

collaboration also became a design principle to im-

prove engagement and learning outcomes. Even with

these genuinely encouraging discoveries, much more

thorough research is required to fully comprehend the

full potential of CVEs.

Future work should focus on several key direc-

tions.Longitudinal studies must explore how CVEs

change people over time and how well social skills

are kept and used in the real world. Gaining a com-

prehension of the degree to which CVE-taught skills

are durable across time and varied situations will offer

helpful understandings regarding their overall sustain-

ability. AI integration into CVEs could also result in

adaptive learning systems that change in response to

user behavior. AI-driven environments offer custom

feedback, immediately change task difficulty, along

with delivering support that fits quite a few individual

needs, to gain optimal engagement as well as wide-

ranging learning. Third, research should explore how

CVEs can supplement every customary therapy, de-

veloping many hybrid models combining virtual tools

with every established intervention, for example, be-

havioral therapy or speech therapy. This integration

could truly lead to therapeutic programs that are ex-

ceptionally all-including and undeniably impactful.

Finally, more study about the role of neurotypical

peers in CVEs is needed. Further research should

be done. Understanding how inclusion really affects

the social development of autistic children might help

guide ways to promote inclusivity and build varied ed-

ucational environments. It’s also important to study

less engaging tools that could use hololens. This is

to check if it gives people with Autism a better learn-

ing experience. In many situations, Mixed Reality has

proven to be generally effective (Farouk et al., 2022).

REFERENCES

Ahmad Basri, M. A. F., Wan Ismail, W. S., Kamal Nor,

N., Mohd Tohit, N., Ahmad, M. N., Mohamad Aun,

N. S., and Mohd Daud, T. I. (2024). Validation

of key components in designing a social skills train-

ing content using virtual reality for high function-

ing autism youth—a fuzzy delphi method. PloS one,

19(4):e0301517.

Cobb, S., Beardon, L., Eastgate, R., Glover, T., Kerr, S.,

Neale, H., Parsons, S., Benford, S., Hopkins, E.,

Mitchell, P., et al. (2002). Applied virtual environ-

ments to support learning of social interaction skills

in users with asperger’s syndrome. Digital Creativity,

13(1):11–22.

Elgarf, M., Abdennadher, S., and Elshahawy, M. (2017).

I-interact: A virtual reality serious game for eye con-

tact improvement for children with social impairment.

In Joint International Conference on Serious Games,

pages 146–157. Springer.

Elshahawy, M., Aboelnaga, K., and Sharaf, N. (2020a). Co-

daroutine: A serious game for introducing sequential

programming concepts to children with autism. In

2020 IEEE global engineering education conference

(EDUCON), pages 1862–1867. IEEE.

Elshahawy, M., Bakhaty, M., Ahmed, G., Aboelnaga, K.,

and Sharaf, N. (2022). Towards developing compu-

tational thinking skills through gamified learning plat-

forms for students with autism. In Learning with tech-

nologies and technologies in learning: Experience,

trends and challenges in higher education, pages 193–

216. Springer.

Elshahawy, M., Bakhaty, M., and Sharaf, N. (2020b).

Developing computational thinking for children with

autism using a serious game. In 2020 24th inter-

national conference information visualisation (IV),

pages 761–766. IEEE.

Farouk, P., Faransawy, N., and Sharaf, N. (2022). Using

hololens for remote collaboration in extended data vi-

sualization. In 2022 26th international conference in-

formation visualisation (IV), pages 209–214. IEEE.

Garfin, D. G. and Lord, C. (1986). Communication as a so-

cial problem in autism. In Social behavior in autism,

pages 133–151. Springer.

Glaser, N. and Schmidt, M. (2022). Systematic literature

review of virtual reality intervention design patterns

for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. In-

ternational Journal of Human–Computer Interaction,

38(8):753–788.

Ke, F. and Moon, J. (2018). Virtual collaborative gaming

as social skills training for high-functioning autistic

children. British Journal of Educational Technology,

49(4):728–741.

Khatab, S., Hijab, M. H. F., Othman, A., and Al-Thani, D.

(2024). Collaborative play for autistic children: A sys-

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

596

tematic literature review. Entertainment Computing,

page 100653.

Laugeson, E. A. and Park, M. N. (2014). Using a cbt

approach to teach social skills to adolescents with

autism spectrum disorder and other social challenges:

The peers® method. Journal of Rational-Emotive &

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 32:84–97.

Mesa-Gresa, P., Gil-G

´

omez, H., Lozano-Quilis, J.-A., and

Gil-G

´

omez, J.-A. (2018). Effectiveness of virtual real-

ity for children and adolescents with autism spectrum

disorder: an evidence-based systematic review. Sen-

sors, 18(8):2486.

Millen, L., Hawkins, T., Cobb, S., Zancanaro, M., Glover,

T., Weiss, P. L., and Gal, E. (2011). Collaborative

technologies for children with autism. In Proceedings

of the 10th international conference on interaction de-

sign and children, pages 246–249.

Mitchell, P., Parsons, S., and Leonard, A. (2007). Using vir-

tual environments for teaching social understanding to

6 adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders. Jour-

nal of autism and developmental disorders, 37:589–

600.

Mosher, M. A. and Carreon, A. C. (2021). Teaching so-

cial skills to students with autism spectrum disorder

through augmented, virtual and mixed reality. Re-

search in Learning Technology, 29.

Noor, H. A. M., Shahbodin, F., and Pee, N. C. (2012). Seri-

ous game for autism children: review of literature. In-

ternational Journal of Psychological and Behavioral

Sciences, 6(4):554–559.

Parsons, S. and Mitchell, P. (2002). The potential of virtual

reality in social skills training for people with autistic

spectrum disorders. Journal of intellectual disability

research, 46(5):430–443.

Parsons, S., Mitchell, P., and Leonard, A. (2004). The

use and understanding of virtual environments by ado-

lescents with autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of

Autism and Developmental disorders, 34:449–466.

Schroeder, R., Heldal, I., and Tromp, J. (2006). The usabil-

ity of collaborative virtual environments and methods

for the analysis of interaction. Presence, 15(6):655–

667.

Standen, P. J. and Brown, D. J. (2006). Virtual reality and

its role in removing the barriers that turn cognitive im-

pairments into intellectual disability. Virtual Reality,

10:241–252.

Steed, A., Spante, M., Heldal, I., Axelsson, A.-S., and

Schroeder, R. (2003). Strangers and friends in caves:

an exploratory study of collaboration in networked ipt

systems for extended periods of time. In Proceedings

of the 2003 symposium on Interactive 3D graphics,

pages 51–54.

Strickland, D. (1996). A virtual reality application with

autistic children. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual

Environments, 5(3):319–329.

Thai, E. and Nathan-Roberts, D. (2018). Social skill fo-

cuses of virtual reality systems for individuals diag-

nosed with autism spectrum disorder; a systematic re-

view. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Er-

gonomics Society Annual Meeting, volume 62, pages

1469–1473. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Ange-

les, CA.

Tromp, J. G., Steed, A., and Wilson, J. R. (2003). System-

atic usability evaluation and design issues for collabo-

rative virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators

& Virtual Environments, 12(3):241–267.

Wang, X., Laffey, J., Xing, W., Galyen, K., and Stichter,

J. (2017). Fostering verbal and non-verbal social in-

teractions in a 3d collaborative virtual learning en-

vironment: a case study of youth with autism spec-

trum disorders learning social competence in isocial.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

65:1015–1039.

Weiss, M. J. and Harris, S. L. (2001). Teaching social

skills to people with autism. Behavior modification,

25(5):785–802.

Navigating Autism: The Role of Collaborative Virtual Reality in Social Skills Development

597