Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a

Developing Field: Case Natural Products

Markus Heikkilä and Jyri Vilko

Dep. Industrial Engineering and Management, LUT-University, Kouvola, Finland

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Collaboration, Networking, Natural Products, Supply Chain.

Abstract: Collaboration networks allow different actors inside the industry to exchange knowledge. The knowledge

exchange plays an important role in innovation and industry development. Companies join collaboration

networks to gain competitive advantages and to gather knowledge from other network members. Acquired

knowledge can support innovation without requiring additional investments from the companies. The Finnish

natural product sector is an immature industry field where the knowledge exchange inside the collaboration

networks is not identified. The study identifies and presents the different collaboration networks and the

explicit and tacit knowledge flow between the actors. We found that collaboration between the actors is

common and there are both formal and informal networks where the knowledge is exchanged. However,

informal networks are more popular, and the exchanged knowledge is mostly in a tacit format. This reflects

the underdevelopment of the sectors, characterized by the informality of its network and the reliance on tacit

knowledge.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge management plays an important role in

organizations when trying to achieve competitive

advantages over other companies. It is especially

important in the developing field where companies do

not have a lot of resources to innovate and develop

their companies. Developing field companies need

this information to successfully expand business to

new market areas and succeed in more competitive

global markets (Tubigi & Alshawi, 2015). Needed

knowledge can be reached through collaboration

networks.

Knowledge management and networking can be

researched with many different approaches. This is

due to the wide scale of different definitions for

knowledge management (Amine Chatti, 2012). This

study will approach knowledge management from

knowledge creation, exchange, and utilization inside

collaboration networks. Focus has been selected to

give a clear picture of the current situation in the

immature industry sector.

The Finnish forestry industry is going through a

structural change. (Lipiäinen & Vakkilainen, 2021)

Timber has been the main product of the Finnish

forestry industry. Timber management has developed

in the last three centuries but the natural product

industry development is still limited (Sheppard et al.,

2020). Nowadays when the forestry industry needs to

make swift for more ecological matters the need for

additional business opportunities from forests is

important. Integrating natural products into the

forestry industry could create more complete

management of the ecosystems of forests (Sheppard

et al., 2020). This would create more new business

sustainable business opportunities for Finnish

forestry.

Past research has identified that there is a lack of

researched information on the natural product sector

(Vaara & Miina, 2014). This study aims to fill that

gap by identifying how knowledge is exchanged and

managed in collaboration networks inside the natural

product sector in Finland. The goal is to identify

collaboration networks inside the industry and

illustrate the types of exchanged knowledge. At the

same time, different knowledge exchange channel

will be identified inside the natural product sector.

Identifying the knowledge management inside these

networks can help the industry optimize networks to

overcome problems with low levels of networking

inside the sector (Vaara & Miina, 2014).

136

Heikkilä, M. and Vilko, J.

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products.

DOI: 10.5220/0013475500003929

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 27th Inter national Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 1, pages 136-146

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Although knowledge management has been

recognized as an important part of business for years

there has been no widely agreed definition for the

term (Amine Chatti, 2012; Fakhar Manesh et al.,

2021). It can be defined through the different

processes it contains. Knowledge management can be

defined as the process of creating, storing, accessing,

and disseminating the organization's intellectual

resources (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020). Knowledge

management is visible inside organizations trough

processes. These processes are for example creating,

disseminating, and using the shared knowledge

(Bhatt, 2001; Shehzad et al., 2024).

Knowledge itself can be divided into two

subgroups that are explicit or tacit knowledge

(Nonaka, 1994). The difference between these

subgroups is the formality of the knowledge. Explicit

knowledge is seen as formal, and it can be transmitted

by systematic language. Tacit knowledge is gathered

from specific actions and is difficult to formalize and

communicate further (Nonaka, 1994). This

knowledge can be learned from trial and error and it

occurs over time (Gardeazabal et al., 2023). Tacit

knowledge is highly person-specific which makes it

difficult to transfer (Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy &

Chitale, 2012).

Knowledge creation is proposed to be an endless

cycle where organizations gather knowledge through

socialization, externalization, combination, and

internalization (Gardeazabal et al., 2023;

Schniederjans et al., 2020). Socialization is the way

when actors use face-to-face communication to pass

the acquired tacit knowledge. Externalization needs

individuals with tacit knowledge to allow

transforming that knowledge into explicit format. A

combination of knowledge is practiced when already

captured explicit knowledge is reformed and added

with other explicit knowledge to create new explicit

knowledge. Internationalization turns explicit

knowledge back to tacit knowledge. This happens

through internalizing explicit knowledge into a

person’s own mental models and know-how. (Amine

Chatti, 2012)

Dissemination of knowledge is defined as a

transfer of knowledge to a focused group (Al Koliby

et al., 2022). Knowledge exchange through

dissemination can happen inside the organization or

between other actors (Huggins et al., 2012).

Knowledge dissemination plays an important role

when creating new innovations (Castaneda & Cuellar,

2020). Innovation ideas are often created through

using old knowledge that is recombined (Gusenbauer

et al., 2023). It also provides the needed security for

actors to make informed decisions in fast-changing

business environments. Dissemination of knowledge

can be difficult. All actors do not have naturally the

expertise to knowledge flow. It needs clear practices

and channels to work properly. Dissemination

channels vary from traditional written channels to

new modern digital channels. Written channels

include books, reports, research, and other written

sources. Digital channels include DVDs, emails,

websites, and other internet sources. The last

dissemination channel is interpersonal

communication. This can happen in different kinds of

events such as seminars, forums, and workshops.

(Lafrenière et al., 2013)

Companies must use the knowledge gathered to

achieve benefits out of it. This process of knowledge

management is defined as the usage of gathered

knowledge. This can be also referred to as the

utilization of knowledge. Knowledge exchange itself

does not create much additional value for companies.

The knowledge must be used to gain competitive

advantages from it. (Ouakouak & Ouedraogo, 2019)

Utilization of knowledge has been seen as a critical

process for turning knowledge into an effect on an

organization's performance. Utilization is the process

of knowledge management that has the biggest effect

on overall performance. (Zaim et al., 2019)

Knowledge management can be also seen as an

important practice when pursuing sustainably.

Knowledge management is a strategic resource for

companies of every size that can obtain sustainable

practices through different knowledge management

processes. (Chopra et al., 2021)

2.1 Collaboration Networks

Companies have multiple drivers for joining

collaboration networks. Collaboration with other

actors has been identified as beneficial for the

companies. Identified benefits include cost reduction,

economies of scale in production, lack of own

resources, increased flexibility, access to new

markets, and increased visibility (Tenhunen, 2006).

On top of these benefits networking with other

companies can perform better knowledge exchange

and acceleration of innovations through networks (Lin

& Lin, 2016). Knowledge can be acquired in various

ways. For small companies, one way is through

networking (Huggins et al., 2012). Networking

enables small companies to use knowledge from other

companies inside the network without their own

resource investments (Puthusserry et al., 2020).

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products

137

Nowadays innovations are not happening only

inside individual companies (Möller et al., 2009).

Instead, more and more innovation occurs inside

networks of organizations. Collaboration allows

companies to gather information from a larger

knowledge pool for innovation (Mu et al., 2008). For

knowledge exchange, this means that knowledge

should flow easily between different actors inside the

network. Without the knowledge sharing between the

actor the benefits of collaboration for innovation

cannot be guaranteed (Wang & Hu, 2020). These

collaboration networks that allow knowledge flow

can be categorized by the formality of relationships

between different actors. The different kinds of

networks are formal and informal networks(Ken G

Smith et al., 1995).

Formal networks can be defined as networks

where different actors have well-structured

connections between them. These connections can be

confirmed for example with contracts or other formal

agreements that will specify how the cooperation is

done (Ken G Smith et al., 1995). Typically contracts

will create either an exchange or strategic link

between the networked companies (Vesalainen,

2007).

The second type of network are informal

networks. In these networks, the connections between

different actors are defined by the personal

relationships of company representatives (Ken G

Smith et al., 1995). These relationships are based on

previous cooperation and friendships of the actors

(Vesalainen, 2007).

Social relationships between networked

companies have their own value to the companies and

the term social capital is used to describe that. Social

capital is defined as social connections that will help

the communication between the different members of

the network and that way create competitive

advantages against other companies outside the

network (Mu et al., 2008). Social capital has been

seen as the foundation for networking (Al-Omoush et

al., 2022). Social capital is playing a major role in the

information exchange between companies (Gölgeci

& Kuivalainen, 2020; Yeşil & Doğan, 2019). Social

activity between organizations is seen as a boost for

knowledge transfer. This is because trust is needed to

share and accept knowledge openly (Li et al., 2015).

2.2 Natural Product Sector

The definition of natural products and the different

terms linked to them varies in the literature (Ahenkan

& Boon, 2011; Smith-Hall & Chamberlain, 2023).

The two other commonly used terms to define natural

products that are growing wild in nature are “Non-

timber forest products” and “Non-wood forest

products (Muir et al., 2020). The definition of these

terms varies between countries and there is no widely

accepted consensus on the term (Ahenkan & Boon,

2011; Smith-Hall & Chamberlain, 2023). In this

research natural products are defined as wild and

semi-natural plants or mushrooms used as such or for

processing. In addition to plants and mushrooms,

natural products also include various products

derived from trees, such as sap, resin, spruce bark,

leaves, bark, and conifers (Rutanen et al., 2023). This

definition is commonly used in the Finnish natural

product sector and fits this research case.

The natural product sector characteristics must be

considered when investigating the knowledge

exchange networks. Most of the companies in the

sector are small and micro-sized companies.

Companies are heterogeneous and have businesses in

multiple industries (Wacklin, 2021). The small size of

companies limits the resources companies can use for

the development of the supply chain.

Underdevelopment of the industry is also seen from

the gaps in knowledge inside the industry. There are

gaps in harvest-, revenue-, and trade figures on

regional, national, and international levels (Sheppard

et al., 2020).

Underdevelopment of the industry is affecting the

supply of natural products inside Finnish markets.

Only 10% of natural berries are picked up yearly and

most of them do not end up for industry or sale (Salo,

2015). For example, most of the natural berries

picked up every year end up for people’s own usage.

Only 41% of picked berries end up in the whole or

direct sales of natural berries. Same time the

availability of natural products has been seen as one

of the bottlenecks of the whole industry (Salo, 2015).

A lack of knowledge prevents new companies from

entering the industry which limits the supply of

natural products. Companies do not have the

knowledge to start new companies that could provide

more capacity for the supply of natural products. Lack

of knowledge also limits the supply of natural

products because companies do not have enough

knowledge and information to anticipate the demand

(Vaara & Miina, 2014).

International and national literature suggests that

information is exchanged inside informal connections

between the different partners inside the natural

product sector. Previous studies suggest that inside

these networks the unformal knowledge exchange is

an important part (Chang et al., 2023; Kämäräinen et

al., 2014). Chang et al., (2023) suggest in their

research of the Canadian natural product sector that

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

138

the most important channel for knowledge is other

companies in the same field. The same knowledge

exchange has been identified in the Finnish

agriculture sector where networking and information

exchange is common (Kämäräinen et al., 2014).

3 RESEARCH DESIGN

3.1 Research Methods

The research follows a two-fold approach. Research

has the basic approach of conceptually integrating

various theories into synthesis. The theory of

knowledge management and exchange is considered

in the context of the Finnish natural products sector

and collaboration networks. The theoretical synthesis

is created based on secondary data. This data is

collected from Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and LUT-

Primo databases. Google Scholar database is used

especially for gathering articles on natural products in

Finland. Other databases were used to confirm the

scientific nature of articles and collect articles about

common theories.

The conceptual theory is tested with a critical

single case study (Flyvbjerg, 2011). The non-causal

goal of the case study is to understand how

knowledge is exchanged inside the natural product

sector in Finland. Case study data was collected from

different companies in the Kymenlaakso region of

Finland. The data were collected through semi-

structured interviews. Interview questions were

selected based on the theoretical background (Voss,

2010). Interview questions were tested and confirmed

to be appropriate for the research by test interviews

conducted with experts in the natural product

industry. Interviews were conducted by telephone and

Microsoft Teams. Interviews were recorded and

littered. Littered material was coded and analyzed to

gather needed information for this research.

Companies were selected to represent a wide

selection of different actors inside the supply chain by

information-oriented selection (Flyvbjerg, 2011).

Companies have different focused areas from

production, sales, and processing. On top of that

informant companies have long experience with

natural products. The quality of the data was

confirmed by collecting the data systematically with

similar interview situations from all the different

actors (Mays & Pope, 2000). Research informant

companies are represented in Table 1.

Table 1: Research actor informants.

Actor Relationship to natural

products

Working

experience in

natural products

1 Picking, Processing,

retail sale

13 years

2 Processin

g

, retail sale 6

y

ears

3 Processin

g

, retail sale 34

y

ears

4 Processin

g

, retail sale 30

y

ears

5 Retail sale 57

y

ears

6 Picking, processing, retail

sale

9 years

7 Processing, retail sale,

p

ickin

g

35 years

To gather more overall information on the sector

and confirm data collected from actors, four experts

in the field were interviewed. Experts were selected

based on their experience in the natural products

sector field nationally and regionally. Data was

gathered from experts with informal conversations

and semi-structured interviews which both were

recorded and analyzed. Interview questions were

selected based on the literature review. The questions

were specifically about information exchange inside

the networks. Expert informants are represented in

Table 2.

Table 2: Expert informants.

Exp. Organizational

role and field

Relation to

natural

products

Experience

in

natural

p

roducts

1 Field expert/

Coordinator

-

Business

developmen

t

Expert/

developer

13 years

2 Processing,

retail sale

-

Education

Expert/

developer

6 years

3 Training

manager

-

Association

(natural

p

roducts)

Expert/

training

34 years

4 Secretary

-

Association

(natural

p

roducts)

Knowledge

dissemination

30 years

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products

139

3.2 Research Process

The research was conducted in a five-step process.

Process parts followed each other and provided a

systematic approach to the research subject. The

research started with a preliminary literature review

which directed to focus and the research gap of this

study. The five steps of research were:

1. Preliminary literature review

2. Research gap definition

3. Integrated literature review

4. Data collection and analysis

5. Theoretical synthesis and validation

The research started with a preliminary literature

review. This step of research made the topic familiar

and worked as an introduction to the topic. During

this step, the keywords and most important references

were identified. Keywords that were identified are:

Knowledge management, collaboration,

collaboration networks, and non-wood forest

products.

A preliminary literature review was followed by

a research gap definition. In this part of the research,

the focus of the research was defined. The definition

was made based on gaps observed in the preliminary

literature review. The founded gap presents the

knowledge exchange in developing the natural

product sector.

Based on the defined research gap the integrated

literature review was conducted. In this part, the most

suitable articles in the context of natural products

were integrated into the research. This created the

theoretical background of the research.

An integrated literature review was followed by

data acquisition and analysis. Based on the literature

review the empirical case for research was identified.

Empirical case study data was collected through

semi-structured interviews which questions and

informant companies were decided based on the

theoretical background. Interviews were recorded,

littered, and coded.

Coded data were analyzed, and similar

observations of informants were gathered. The

existing actors in the network were typed and grouped

to better understand the network as a whole and the

role of the different groups (Hakanen et al., 2007). In

addition, the boundaries of the network were defined

(Monaghan et al., 2017). In this work, the network has

been limited to the actors operating in the natural

products sector in the region of Kymenlaakso. Based

on that the network collaboration and knowledge

transfer between the different actors were identified.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Collaboration is an important part when knowledge is

exchanged between different actors inside the

networks. From the interviews conducted for

companies, the different collaborations and

knowledge exchange inside networks were identified.

The collaboration networks can be divided into

formal and informal categories based on the

theoretical background.

4.1 Formal Collaboration

Formal partnerships are based on the exchange of

various natural products, either between operators or

from operators to customers. In terms of product

exchange, three of the operators had formal

agreements in place to organize the sale and role of

the products. Role-playing and bartering operate both

between the different stages of the supply chain and

within the same stage of the supply chain. There is

contractual protection of bartering between the

different roles in the supply chain when buying

natural products as raw materials from the larger

players in the sector. Sellers at the same stage of the

supply chain enter contracts to sell other products in

their own shops and on the common market. This is

exemplified by the various markets and sales at these

markets. Before entering the market, agreements are

concluded between the actors. In this way, firms

selling different products can correctly distribute the

profits from the market between the actors. In

addition, the different business models and tax rates

of different operators require these agreements to be

maintained. Contract details about quantities and

quality is exchanged with digital channels like email

and telephone.

In addition to formal cooperation based on

exchange, small-scale strategic cooperation was also

identifiable in the sector. Strategic cooperation was

for example, by selling the products of another

network member in their own shop. In addition, one

of the operators interviewed had created joint

marketing material with another company. The aim

of these activities was to grow the business of both

companies together. Despite the formal agreements

between the actors, the base for these collaborations

is still between the companies’ relationships. Actors

have made often informal collaborations between

actors before transforming it to a more formal format.

Despite the formality of the collaboration network

the knowledge creation and exchange is mostly

informal. Knowledge is tacit that actors have gained

from their own experiences. This knowledge is shared

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

140

interpersonally face-to-face in different kinds of

situations when formal partners meet each other.

Interviewees stated that they exchange knowledge

with their formal partners to help them survive better

on the market. This knowledge is tacit and only in the

actors’ own knowledge base.

Formal explicit knowledge exchange occurs

when actors are in collaboration with the associations

of the natural product sector. These collaboration

relationships are formal and need registration from

the actors. The association disseminates the explicit

information about the industry to the actors.

Associations use mainly digital channels like email

and websites for explicit knowledge dissemination.

4.2 Informal Collaboration

In addition to formal cooperative relationships, some

relationships operate informally on the basis of trust.

For example, some of the natural berries are sourced

between companies purely on the basis of trust. In an

example situation, the picker knows when to bring the

berry to the marketplace, and through this the berry

retail sellers buy it. The purchase volumes are not

agreed in advance by contract but take place on an as-

needed basis. The same applies to the sale of other

natural products. The interviews showed that other

natural products are also bought without prior

agreements. These trade and cooperation

relationships are based on trust built up over a long

period of time and knowledge of who has what to

offer which product. Companies operating in the

sector know what others have to offer and therefore

know where to get the products they need. This

ensures that actor is receiving natural products in

desired quality. The quality of products is really

important for the actors.

The exchange of information between companies

is mainly done using traditional information

exchange systems. These channels include face-to-

face conversations, telephone, and e-mail.

Information and advice on the sector are provided

face-to-face and by telephone. By telephone,

operators contact well-known actors who have been

active in the sector for a long time to get advice for

working inside the industry. Long-established actors

play an important role in the networks by passing on

knowledge to newcomers. They have created the

knowledge based their own experience and trial an

error action. Face-to-face discussions take place

alongside various events. These include events, fairs,

and markets. Market traders involved in the sale of

natural products to consumers share knowledge with

each other by holding discussions with other traders

on the edge of the market. In addition to the

traditional means of information exchange, informal

networks have their own private closed WhatsApp

groups through which information is shared within

the network. These closed communities discuss, for

example, where to find different natural products in

the area. Closed networks are difficult to get into and

information does not flow freely to other actors in the

sector. Inside these closed networks happens the

knowledge transformation to explicit format. Actors

with knowledge will write it down to other actors

inside these groups and that way make it more easily

transformable.

With long-standing partnerships, operators know

exactly what services and products each offers. This

makes it easier, for example, to organize different

kinds of experience services, knowing where to get

what kind of service. Here, too, trust plays an

important role. It is important for operators to be able

to get the service they need, even if they are not in

active contact with each other. This is also the basis

for selecting those partner companies that really want

to cooperate. In general, with the exception of one

operator, collaboration was perceived as very

important. The importance of collaboration is also

reflected in the attitudes of operators towards

companies that do not cooperate. Three of the

operators mentioned how operators who do not want

to cooperate easily end up as outsiders in the sector.

The natural products sector is particularly small in the

Kymenlaakso region, so a partner who is perceived as

difficult to work with is easily excluded from the

network of the whole region. For example, those who

are negative towards cooperation were considered

impossible to cooperate with and were therefore

excluded from both formal and informal

collaboration networks. Long relationships operate as

a promise of quality for actors. Actors want to

maintain product quality. This helps to build brand

value as sustainable, clean, and high-quality natural

products. Actors’ states that the brand image of

products is concerned when new collaboration

relationships are agreed upon.

4.3 Expanding the Collaboration

Networks

As we have seen from the current state of networks,

cooperation, and networking are common in the

natural products sector. Despite their prevalence, the

organization between actors is still rather informal.

This informality may hinder the development of the

sector, as it creates uncertainty, for example actors’

states that the availability of different natural products

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products

141

can be uncertain. All the operators interviewed were

positive about extending networking. This positive

attitude is likely to be influenced by the positive

attitude towards cooperation that has been noted

previously. The positive attitude of the actors towards

cooperation will enable the expansion of networks

and more formal structures in the future.

During the interviews, the actors were asked what

kind of activity would be appropriate as the network

expanded. Five interviewees mentioned contracts as

the best way, if possible. Two operators could not

comment on how expansion could be agreed.

Operators were also asked about their interest in

setting up a cooperative around the natural products

sector. However, this received the most negative

response. None of the actors saw a cooperative as a

good option for expanding the network. One operator

saw a cooperative as a potentially viable solution for

the collection of natural products but not for a wider

activity. Other operators were even more critical and

did not see any use for it.

However, formalism is not to the liking of all

actors in the sector. One actor states that contracts to

be too burdensome. The contracts are perceived as too

burdensome, especially for small operators, and as a

result, they do not want to be bound by them. In

particular, the excessive costs incurred through

contracts are seen as an obstacle to the expansion of

cooperation in small businesses. This problem has

also been identified by experts in the field. In their

interviews, they mentioned how it has been a

challenge to get companies to join natural product

association networks. The associations in the sector

have tried to create various schemes and networks

through which, for example, collectors could meet

businesses in need of natural products. Despite these

networks, businesses have not adopted them in the

desired way, which has hampered the development of

the natural products sector. The lack of networks has

prevented businesses from obtaining the natural

products they need, as there is no time to collect them

after late notification.

4.4 Knowledge Exchange Bottlenecks

Knowledge is tacit and shared informally face-to-face

in different kinds of situations. Interviewees stated

that these conversations are done in both formal and

informal events. Actors meet their collaboration

partners inside formally organized events such as

market sales and seminars, but the knowledge is

mostly transferred informally face-to-face. The tacit

knowledge of actors is acquired through years of

experience.

The informal knowledge piles up for a couple of

main actors of the network. Interviewees stated that

they have some connection to actors with a long

career in the sector. This will make it difficult for

anybody outside the ongoing networks to join. The

piled-up knowledge is also problematic for the

continuity of knowledge. Knowledge acquired by

these long-career actors might not totally end up to

other actors. This can lead to a loss of knowledge that

could slow down the development of the sector.

Industry informality makes this problem more

visible. Inside informal networks, trust plays an

important role. Generally, networking increases the

trust between the actors inside networks and

decreases the trust to actors outside the network

(Fuller-Love, 2009). To gather this trust the new actor

must be accepted by the other actors inside the

network. It is often a long time, and that way will

prevent new companies from entering the sector and

reduces the possibilities for short-term

collaboration. This will slow down the innovation

inside the networks when there is no new knowledge

outside the network. This is problematic when the

actors are trying to overcome the biggest problems of

the industry right now. These include the problems

with supply and demand. Pickers do not get

information soon enough to fulfill all the orders from

the other actors in the supply chain. These problems

could be overcome with more formal and easier

platforms to acquire new information without the

need for long term collaboration in networks. The

informal tacit information should be transformed into

more explicit information on systemic level and so

that it could be provided easily for new companies

inside the industry.

Development towards this is also the wish of

interviewees. As networks develop, most actors

would like to see them formalized. Formalization

would ensure a clear distribution of costs and ensure

continuity of cooperation. Contractual cooperation

agreements would ensure that the various operators

receive the fees due to them, thus creating a

sustainable and long-term cooperative relationship.

The network would be used to organize freezing and

joint events. An enlarged network would aim to

generate business all year round, for example through

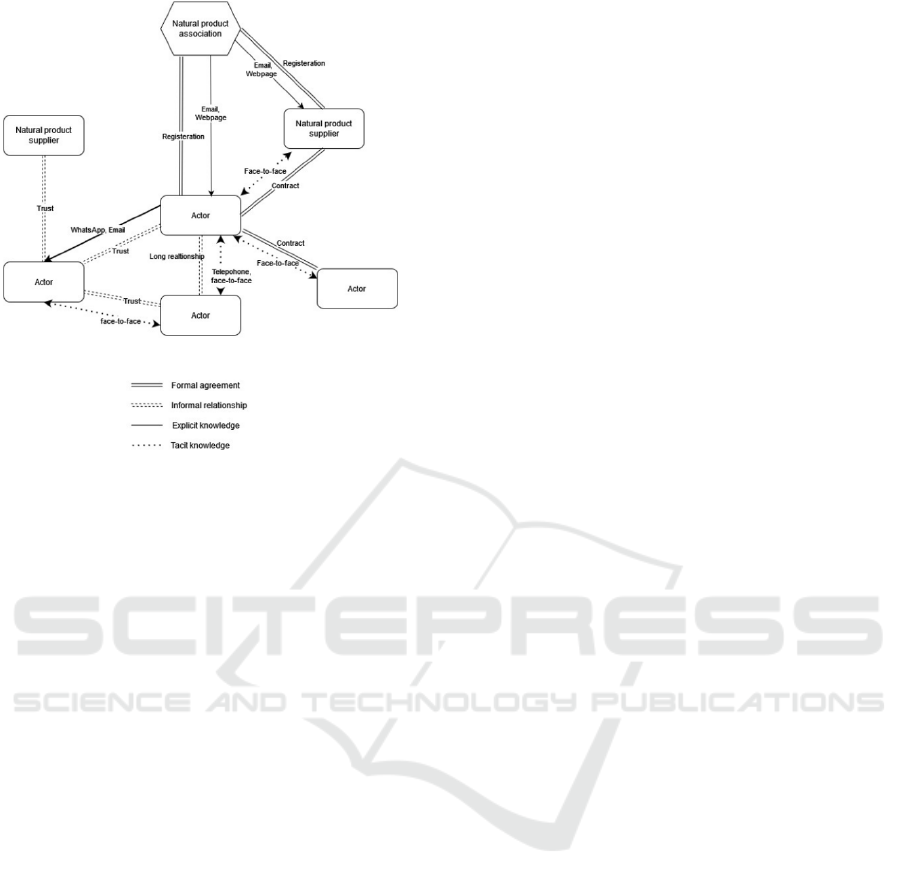

sales fairs. The current state of observed collaboration

and knowledge exchange is represented in Figure 1.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

142

Figure 1: Current state of observed collaboration and

knowledge exchange

4.5 Discussion

The development of the natural product sector is still

in its early stages. The immature nature of

relationships can be identified from the informal

relationship between the companies. These

relationships are key parts when actors are

transferring knowledge to each other. This confirms

the previous studies that had noticed similar results

from the natural product sector and Finnish

agriculture (Chang et al., 2023; Kämäräinen et al.,

2014). Different actors inside collaboration networks

have strong trust in each other. Actors have strong

relationships with other actors and the trust is made

through social capital. Social capital enables the trust

between partners to be open from knowledge

exchange (Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, 2020).

Immature nature was also confirmed by the

knowledge transfer inside collaboration networks.

Knowledge is in tacit format and is linked with actors

with long experience in the field. This creates

difficulties in the dissemination of this knowledge

(Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy & Chitale, 2012).

Knowledge is not transformed to explicit format and

that way can only transferred with communication.

This is a problem specially when the actor's

relationships with each other are informal.

Communication is made in traditional and digital

ways. Despite the use of digital channels most of

knowledge is not saved for websites or other more

formal channels (Lafrenière et al., 2013).

Collaboration is popular and actors do want to

develop that. Actors are open to knowledge

dissemination and that is encouraged. Collaboration

is expected from new actors joining the sector. Still,

there are bottlenecks. This can be seen as a result of

to the immature nature of the sector. Effective

dissemination of knowledge needs trust, openness,

and powerful strategies to work properly. (Li et al.,

2015) The sector has strong trust between different

collaboration actors, but the structured way of

knowledge is still rare. This also reflects the

transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit.

The lack of structured ways of knowledge

dissemination might be due to the small size of the

companies. Micro and small-sized companies have

limited resources to innovate and create new business

opportunities(Lin & Lin, 2016). This can be seen as

actors might not have enough resources and expertise

to implement effective dissemination strategies after

the main business of companies.

Actors are utilizing the knowledge they can

gather. This makes knowledge management a

powerful tool for actors. Utilization makes it possible

to benefit from the knowledge pool that is available

through collaboration (Ouakouak & Ouedraogo,

2019). Still, the bottleneck stays in the dissemination

of knowledge, and that way all the knowledge is not

available for utilization. This confirms the previous

studies that have found that there is still a lack of

knowledge in the natural product sector.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge management can lead to competition

advantages for companies and collaboration

networks. Knowledge management processes are in

critical part when investigating the real effects of

knowledge management This becomes more

important when working with development and

immature fields. Small companies can fill the lack of

resources with the knowledge acquired from

collaboration networks. This research identified the

collaboration networks where knowledge is created

and exchanged inside natural product sector.

5.1 Scientific Implications

Knowledge management is an important part of a

company's competitiveness (Tubigi & Alshawi,

2015). Companies must handle the different

processes inside the knowledge management to get

real benefit out of it. The most important processes

are the dissemination and utilization of knowledge.

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products

143

Especially the utilization of knowledge is important

because it realizes the value of knowledge.

Knowledge can be generated and transmitted in a

lot of different ways. The creation of knowledge can

differ between the different types of knowledge.

Informal tacit knowledge needs powerful practices

for the dissemination of knowledge. This needs often

the socialization between different actors or

transformation to a more explicit easier to transfer

format(Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy & Chitale,

2012).

These social actions are critical when creating

innovations and creating new business opportunities

in a developing field (Möller et al., 2009). Social

activities can occur inside different kinds of

networks. These networks create a platform for

different actors to collaborate and change information

with each other. Collaboration networks can be

divided into two groups based on the formality of the

collaboration connections.

Finally, the knowledge gathered from

collaboration networks needs to be used. Utilization

of gathered knowledge is the key part of actually

achieving additional value. Without powerful

utilization, the knowledge creation and dissemination

can be pointless (Ouakouak & Ouedraogo, 2019).

5.2 Managerial Implications

Collaboration inside the natural product sector in

Finland is common. Different actors in different

states of the supply chain have positive attitudes

towards collaboration. Collaboration is seen as the

way how the industry sector could develop. From the

industry, the formal and informal networks were

identified.

Formal networks are built around the exchange of

goods between actors. These goods include different

kinds of natural products for wholesale and

processing. Inside these relationships, the contracts

play an important role. Contracts have been made

about the amounts and quality of needed natural

products. Some strategic collaborations can be

identified but they are still small and unsystematic.

Most of these formal network connections are built

on top of the informal relationships between company

persons. The friendship creates a good collaboration

base for a deeper more formal connection.

Alongside these formal networks are the informal

networks. Inside these networks, collaboration is

made from the exchange of goods to helping friends

in the same industry. The relationships between

persons inside companies have a strong impact on

how deep the collaboration is.

Knowledge is shared in both networks between

actors. Most of the shared knowledge is in tacit

format and is exchanged in different kinds of

situations face-to-face and by telephone. Actors with

long careers in the industry have an important role in

disseminating knowledge to other actors. They have

the knowledge base of the industry which can be used

for industry development. Tacit information can work

as a bottleneck when trying to develop the field. It is

difficult to disseminate effectively and can rule new

actors outside of the industry.

5.3 Limitations and Further Research

This study offers a limited view of the research due to

the case study nature of the research. The collected

data is limited to one region and should be extended

in further research. Future research should be

focusing the way how the knowledge could be

transformed into a more formal format and extend

also out of the networks for new actors in the industry.

This could help the development of the whole

industry to overcome the bottlenecks of knowledge.

Further research is needed for providing better

network analyse of the industry. The sample size of

this research did not provide enough evidence to tell

the extent of the network.

REFERENCES

Ahenkan, A., & Boon, E. (2011). Non-Timber Forest

Products (NTFPs): Clearing the Confusion in

Semantics. Journal of Human Ecology, 33(1), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2011.11906342

Al Koliby, I. S., Mohd Suki, N., & Abdullah, H. H. (2022).

Linking knowledge acquisition, knowledge

dissemination, and manufacturing SMEs’ sustainable

performance: The mediating role of knowledge

application. The Bottom Line (New York, N.Y.), 35(4),

185–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-12-2021-0123

Al-Omoush, K. S., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Lassala, C., &

Skare, M. (2022). Networking and knowledge creation:

Social capital and collaborative innovation in

responding to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of

Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 100181.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100181

Amine Chatti, M. (2012). Knowledge management: A

personal knowledge network perspective. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 16(5), 829–844.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271211262835

Antunes, H. de J. G., & Pinheiro, P. G. (2020). Linking

knowledge management, organizational learning and

memory. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 5(2),

140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2019.04.002

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

144

Bhatt, G. D. (2001). Knowledge management in

organizations: Examining the interaction between

technologies, techniques, and people. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 5(1), 68–75.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270110384419

Castaneda, D. I., & Cuellar, S. (2020). Knowledge sharing

and innovation: A systematic review. Knowledge and

Process Management, 27(3), 159–173.

https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1637

Chang, C.-T., Gorby, T. A., Shaw, B. R., Solin, J.,

Robinson, P., Tiles, K., & Cook, C. (2023). Influence

of learner characteristics on optimal knowledge

acquisition among Wisconsin maple syrup producers.

The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension,

1–23.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2023.2254286

Chopra, M., Saini, N., Kumar, S., Varma, A., Mangla, S.

K., & Lim, W. M. (2021). Past, present, and future of

knowledge management for business sustainability.

Journal of Cleaner Production, 328, 129592-.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129592

Fakhar Manesh, M., Pellegrini, M. M., Marzi, G., & Dabic,

M. (2021). Knowledge Management in the Fourth

Industrial Revolution: Mapping the Literature and

Scoping Future Avenues. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 68(1), 289–300.

https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2019.2963489

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. The Sage Handbook of

Qualitative Research, 4, 301–316.

Fuller-Love, N. (2009). Formal and informal networks in

small businesses in the media industry. International

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(3), 271–

284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0102-3

Gardeazabal, A., Lunt, T., Jahn, M. M., Verhulst, N.,

Hellin, J., & Govaerts, B. (2023). Knowledge

management for innovation in agri-food systems: A

conceptual framework. Knowledge Management

Research & Practice, 21(2), 303–315.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1884010

Gölgeci, I., & Kuivalainen, O. (2020). Does social capital

matter for supply chain resilience? The role of

absorptive capacity and marketing-supply chain

management alignment. Industrial Marketing

Management, 84, 63–74.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.05.006

Gusenbauer, M., Schweiger, N., Matzler, K., & Hautz, J.

(2023). Innovation Through Tradition: The Role of Past

Knowledge for Successful Innovations in Family and

Non-family Firms. Family Business Review, 36(1), 17–

36. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865221147955

Hakanen, M., Heinonen, U., & Sipilä, P. (2007).

Verkostojen strategiat: Menesty yhteistyössä. Edita.

Huggins, R., Johnston, A., & Thompson, P. (2012).

Network Capital, Social Capital and Knowledge Flow:

How the Nature of Inter-organizational Networks

Impacts on Innovation. Industry and Innovation, 19(3),

203–232.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2012.669615

Kämäräinen, S., Rinta-Kiikka, S., & Yrjölä, T. (with

Pellervon taloustutkimus). (2014). Maatilojen välinen

yhteistyö Suomessa (eng. Cooperation Between Farms

in Finland). Pellervon taloustutkimus.

Ken G Smith, Stephen J Carroll, & Susan J Ashford. (1995).

INTRA- AND INTERORGANIZATIONAL

COOPERATION: TOWARD A RESEARCH

AGENDA. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 7–

23. https://doi.org/10.2307/256726

Lafrenière, D., Menuz, V., Hurlimann, T., & Godard, B.

(2013). Knowledge Dissemination Interventions: A

Literature Review. SAGE Open, 3(3),

215824401349824-.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013498242

Li, Y., Shi, D., Li, X., & Wang, W. (2015). Influencing

factors of knowledge dissemination in rural areas in

China. Nankai Business Review International, 6(2),

128–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-05-2014-0026

Lin, F.-J., & Lin, Y.-H. (2016). The effect of network

relationship on the performance of SMEs. Journal of

Business Research, 69(5), 1780–1784.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.055

Lipiäinen, S., & Vakkilainen, E. (2021). Role of the Finnish

forest industry in mitigating global change: Energy use

and greenhouse gas emissions towards 2035. Mitigation

and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 26(2), 9.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09946-5

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in

qualitative research. BMJ : British Medical Journal,

320(7226), 50–52.

Möller, K., Rajala, A., & Svahn, S. (2009). Tulevaisuutena

liiketoimintaverkot, Johtaminen ja arvonluonti (3. P.).

Teknologiateollisuus.

https://researchportal.tuni.fi/en/publications/tulevaisuu

tena-liiketoimintaverkot-johtaminen-ja-arvonluonti-3-

p

Monaghan, S., Lavelle, J., & Gunnigle, P. (2017). Mapping

networks: Exploring the utility of social network

analysis in management research and practice. Journal

of Business Research, 76, 136–144.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.020

Mu, J., Peng, G., & Love, E. (2008). Interfirm networks,

social capital, and knowledge flow. Journal of

Knowledge Management, 12(4), 86–100.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270810884273

Muir, G. F., Sorrenti, S., Vantomme, P., Vidale, E., &

Masiero, M. (2020). Into the wild: Disentangling non-

wood terms and definitions for improved forest

statistics. International Forestry Review, 22(1), 101–

119.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation. Organization Science

(Providence, R.I.), 5(1), 14–37.

https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

Ouakouak, M. L., & Ouedraogo, N. (2019). Fostering

knowledge sharing and knowledge utilization: The

impact of organizational commitment and trust.

Business Process Management Journal, 25(4), 757–

779. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-05-2017-0107

Puthusserry, P., Khan, Z., Knight, G., & Miller, K. (2020).

How Do Rapidly Internationalizing SMEs Learn?

Exploring the Link Between Network Relationships,

Knowledge Management in Sustainable Supply Chains in a Developing Field: Case Natural Products

145

Learning Approaches and Post-entry Growth of

Rapidly Internationalizing SMEs from Emerging

Markets. Management International Review, 60(4),

515–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-020-00424-9

Rutanen, J., Wacklin, S., & Partanen, B. (2023, March).

Kestävästi ja vastuullisesti monipuolista arvonlisää—

Luonnontuotealan toimintaohjelma 2030 (eng.

Sustainably and Responsibly Creating Diverse Added

Value—The Natural Products Sector Action Plan 2030)

available at: https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/e32dd654-

cb4d-4a9d-b58d-faba0513b3d9

Salo, K. (2015). Metsä: Monikäyttö ja ekosysteemipalvelut

(eng. Forest: Multiple Use and Ecosystem Services)

https://jukuri.luke.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/520558/L

uke-Mets%E4-

Monik%E4ytt%F6jaekosysteemipalvelut.pdf?sequenc

e=1

Schniederjans, D. G., Curado, C., & Khalajhedayati, M.

(2020). Supply chain digitisation trends: An integration

of knowledge management. International Journal of

Production Economics, 220, 107439.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.07.012

Shehzad, M. U., Zhang, J., Dost, M., Ahmad, M. S., &

Alam, S. (2024). Knowledge management enablers and

knowledge management processes: A direct and

configurational approach to stimulate green innovation.

European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(1),

123–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-02-2022-0076

Sheppard, J. P., Chamberlain, J., Agúndez, D.,

Bhattacharya, P., Chirwa, P. W., Gontcharov, A.,

Sagona, W. C. J., Shen, H., Tadesse, W., & Mutke, S.

(2020). Sustainable Forest Management Beyond the

Timber-Oriented Status Quo: Transitioning to Co-

production of Timber and Non-wood Forest Products—

a Global Perspective. Current Forestry Reports, 6(1),

26–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-019-00107-1

Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy, K., & Chitale, C. M. (2012).

Collaborative knowledge sharing strategy to enhance

organizational learning. The Journal of Management

Development, 31(3), 308–322.

https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711211208934

Smith-Hall, C., & Chamberlain, J. (2023). Environmental

products: A definition, a typology, and a goodbye to

non-timber forest products. International Forestry

Review, 25(4), 491–502.

https://doi.org/10.1505/146554823838028247

Tenhunen, J. T. (2006). Johdon Laskentatoimi

Kärkiyritysverkostoissa, soveltamismahdollisuudet ja

yritysten tarpeet (eng. Management Accounting in

Leading Enterprise Networks, Application Possibilities

and Business Needs).

https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/31137

Tubigi, M., & Alshawi, S. (2015). The impact of knowledge

management processes on organisational performance:

The case of the airline industry. Journal of Enterprise

Information Management, 28(2), 167–185.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2014-0003

Vaara, M., & Miina, S. (2014). Luonnontuotealan

ennakointi. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/229379

Vesalainen, J. (with Teknologiateollisuus). (2007).

Kaupankäynnistä kumppanuuteen: Yritystenvälisten

suhteiden elementit, analysointi ja kehittäminen (eng.

From Trade to Partnership: Elements, Analysis, and

Development of Interfirm Relationships).

Teknologiainfo Teknova.

Voss, C. (2010). Case research in operations management.

In Researching operations management (pp. 176–209).

Routledge.

Wacklin, S. (2021). Tulevaisuuden luonnontuoteala (eng.

The Future of the Natural Products Sector) Työ- ja

elinkeinoministeriö (Ministry of Economic Affairs and

Employment)

https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/16366

9

Wang, C., & Hu, Q. (2020). Knowledge sharing in supply

chain networks: Effects of collaborative innovation

activities and capability on innovation performance.

Technovation, 94–95, 102010-.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2017.12.002

Yeşil, S., & Doğan, I. F. (2019). Exploring the relationship

between social capital, innovation capability and

innovation. Innovation (North Sydney), 21(4), 506–

532. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2019.1585187

Zaim, H., Muhammed, S., & Tarim, M. (2019).

Relationship between knowledge management

processes and performance: Critical role of knowledge

utilization in organizations. Knowledge Management

Research & Practice, 17(1), 24–38.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2018.1538669

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

146