Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative

Learning Context Using Computational Resources

Gabriela C. dos Santos

a

, Deivid E. Silva

b

, Rachel D. Reis

c

and Natasha M. C. Valentim

d

Department of Informatics, UFPR, Federal University of Paran

´

a, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

Keywords:

Collaborative Learning, 3C Model, LX Evaluation, Learner eXperience.

Abstract:

It is important to evaluate the Learner eXperience (LX) in a collaborative learning context, as there is a need

to support students in their Practical work (PWs) groups that are beyond their reach. Therefore, this paper

presents an exploratory study to investigate LX and collaborative learning using computational resources. 31

learners and a teacher of the Requirements Engineering subject participated in this study. Data collection was

carried out using a questionnaire based on the 3C Model of collaboration (communication, coordination, and

cooperation), and the results were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. The findings made it possible to

identify strengths, needs, difficulties, and weaknesses. One of the strengths identified is that the learners had

the freedom to choose their roles and felt comfortable. One of the difficulties identified was the frequency and

availability of the learners for discussions and development of the PWs, as it occurred unevenly, with reports

that there was a lack of commitment from some learners.

1 INTRODUCTION

Collaborative learning is two or more students work-

ing in groups with shared objectives, helping each

other to build knowledge (Torres and Irala, 2014). In-

aba et al. (2020) point out that interaction among

students is partially surrounded by relationships be-

tween group members, which suggests that effective

grouping is essential to achieve the benefits of collab-

orative learning. Therefore, it is crucial to organize

students to develop skills such as argumentation, ne-

gotiation, conflict resolution, and sharing ideas. It is

believed that despite advances in the area of collab-

orative work, it is known that learners have different

communication, coordination, and cooperation skills,

and collaborative learning is not always practical for

all learners (Inaba et al., 2000).

Given this, it became necessary to investigate how

collaborative learning can impact the Learner eXpe-

rience (LX), considering the diversity of learners and

seeking to provide more effective and positive experi-

ences. The evaluation of LX in a collaborative learn-

ing context is believed to be necessary, as students

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0864-1534

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1066-0750

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3747-9508

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6027-3452

need to be supported in their learning experiences dur-

ing PW to improve communication, coordination, and

cooperation skills. Huang et al. (2019) recommend

that LX be evaluated holistically to ensure all aspects

of the experiences are considered. In this sense, we

consider cooperation, communication, and coordina-

tion to be elements of investigating LX.

In this sense, an exploratory study was carried out,

as it is used to discover new and relevant insights for

the research topic (Swedberg, 2020). Thus, the study

sought to answer the question: “What are the per-

ceptions and experiences of learners in a collabora-

tive learning context with the use of computational

resources?”. The study aimed to investigate and eval-

uate LX, learner communication, coordination, and

cooperation (based on the 3C Model of collabora-

tion (Fuks et al., 2008)) using computer resources.

The study was conducted face-to-face with 31 learn-

ers studying the Requirements Engineering (RE) sub-

ject of the course in Computer Science and Biomed-

ical Informatics (CS & BI) at the Federal University

of Paran

´

a (UFPR) in Brazil. The learners’ responses

were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively. The

findings showed that some learners enjoyed the expe-

rience of working collaboratively, while others had a

more negative experience. Based on the 3Cs of col-

laboration, it is believed that LX was different for

each learner, and the friendship/partnership relation-

950

Santos, G. C., Silva, D. E., Reis, R. D. and Valentim, N. M. C.

Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative Learning Context Using Computational Resources.

DOI: 10.5220/0013477600003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 950-957

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

ship among the learners made a difference in the more

satisfactory development of PWs.

This study contributes to the area of Informat-

ics in Education, Computer Education, and Human-

Computer Interaction (HCI) by providing evidence

through the investigation of LX evaluation in a col-

laborative learning context using computational re-

sources. The use of computational resources is inter-

esting in this context, as they enhance the interaction

and communication of group members in PWs. By in-

tegrating these research topics, we analyze and iden-

tify the weaknesses, needs, difficulties, and strengths

within this context. In addition, we provide new in-

sights into LX and help teachers analyze their teach-

ing strategies to enhance their LX. We also aim to

provide learners with a more holistic, engaging, and

memorable LX (Huang et al., 2019) through commu-

nication, coordination, and cooperation skills.

2 BACKGROUND

Huang et al. (2019) define LX as learners’ percep-

tions, responses, and performance through interaction

with a learning environment, educational resources,

and so on. Schmidt and Huang (2022) define LX

as the class of users (the learner) engaged in a spe-

cific task (related to learning) while using a different

type of technology (a technological tool designed for

learning). For this research, the term LX is specifi-

cally related to the perceptions, responses, and perfor-

mance of learners while interacting with educational

resources in a collaborative context.

Reflecting on the concepts of LX presented, one

can ask what constitutes LX and why it is essential to

evaluate it. In this sense, it is necessary to observe,

analyze, and evaluate the elements present in this ex-

perience (dos Santos et al., 2023). Thus, the definition

of LX lies not only in achieving the desired results

but also in the learner’s satisfaction and other subjec-

tive experiences, such as confidence. In this context,

computer resources are one of the most critical fac-

tors for improving LX, which, according to Huang et

al. (2019), results in more engaging and memorable

educational experiences. Therefore, LX assessment is

centered on learner interactions because, according to

Zeichner (2003) through assessment, it will be possi-

ble to value the existential experiences of learners.

Cooperation, communication, and coordination

can be considered LX elements, and these elements

are presented in the 3C collaboration model (Fuks

et al., 2008). Fuks et al. (2008) explain that the three

dimensions of this model should not be addressed in

isolation, as they are interdependent. In this sense,

the authors defined communication as the exchange

of messages, coordination as the management of peo-

ple, activities, and resources, and cooperation as the

execution of tasks in a shared space. Collaborative

systems are positioned in a triangular space, with the

vertices representing the three dimensions of collab-

oration (Fuks et al., 2008). Although the aim of a

system may be to specifically support one of the Cs,

it will not fail to include aspects of the other Cs.

Fuks et al. (2008) show that, based on the 3C

model, it is possible to identify the constituent ele-

ments of a synchronous communication tool and clas-

sify them according to the three dimensions. The

communication dimension includes the following el-

ements: language (written, spoken, pictorial, or ges-

tural), transmission (one-off or continuous), and cat-

egorization (type of speech, discourse, or emotion).

The coordination dimension includes the following

elements: topic, access (who or how many can take

part in the conversation), availability (status of the

participant), roles (assignment of roles), frequency,

addressing (indication of the recipient) and evaluation

(qualification of the messages, participants or discus-

sions). For the cooperation dimension, there are the

elements: recording (storing messages and discus-

sions) and space configuration (viewing and retriev-

ing messages) (Pimentel et al., 2006).

3 EXPLORATORY STUDY

The exploratory study was conducted to discover

new and relevant insights (Swedberg, 2020) for the

research topic. In this sense, this study was car-

ried out to investigate and evaluate the learners’

experiences, communication, coordination, and col-

laboration (based on the 3C model of collabora-

tion (Fuks et al., 2008)) using computer resources.

The study was approved by the researcher’s insti-

tution’s Research Ethics Committee under CAAE:

84496124.0.0000.0102.

About population and sample, the study was

conducted with learners from the (CS & BI) courses

taking the RE subject at UFPR and with the respec-

tive teacher of this subject. The teacher was invited

to participate in the study through an invitation letter

sent by email. After accepting voluntarily, the teacher

received the study guidelines. Together with the re-

searchers and authors of this paper, the teacher invited

the learners to participate in the study during one of

the face-to-face classes, explaining the purpose of the

study and what their participation would consist of.

As prerequisites for the learner’s participation, he/she

would need to: be enrolled in the RE subject; have

Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative Learning Context Using Computational Resources

951

carried out the PWs collaboratively; and have carried

out the PWs using computational resources. At this

point, the 31 learners who expressed interest in par-

ticipating in the study.

About context, one of the requirements for con-

ducting the study in the RE subject is that the PWs

should be collaborative. In this sense, the teacher in-

formed us that she had planned for them to be carried

out collaboratively. The RE subject was planned and

organized by the teacher without interference from

the researchers. The subject consists of three PWs.

Thus, the exploratory study was carried out at the end

of the last PW of the RE subject. The teacher also in-

formed us that she left the learners free to form groups

of four to six learners. As general guidelines, were to

apply the practice of peer review, in which a learner

should review the work of another learner in the group

and document it.

PW1 consisted of eliciting requirements for an in-

novative mobile or web application. To carry out

PW1, the teacher organized it in three steps: first,

defining the team; second, eliciting the requirements;

and third, delivering and presenting PW1. For the

first step, the guidelines were: to form groups; create

contact groups on social networks (suggestion, What-

sApp, Discord, among others); and manage the sched-

ules and deadlines for executing PW1. For the second

step, requirements elicitation, the guidelines were:

each group should use at least four different require-

ments elicitation techniques to elicit requirements for

a mobile or web application and document them in a

report; for each technique used, the group should add

to the report the artifacts used in the process of apply-

ing the technique, as well as the results achieved; for

each of the techniques used, the group should explain

how the technique helped in the requirements elici-

tation process. In addition, they should add all the

problems and difficulties faced by the team during the

application of each technique; present the list of func-

tional and non-functional requirements elicited, and

point out which technique helped to obtain each re-

quirement. The third step consisted of delivering the

report and presenting PW1 to the other colleagues.

PW2 consisted of developing a report containing

use cases, activity diagrams, state diagrams, and con-

ceptual class diagrams. The teacher suggested contin-

uing with the same group, as defined in PW1. Another

suggestion for PW2 was to consider the system pro-

posed in PW1. Moreover, the groups presented PW2

to other colleagues. PW3 consisted of building low or

medium-fidelity mobile application prototypes. This

PW is a continuation of PW1 and PW2, in which the

learners had to analyze the information in the previous

reports to develop the prototypes. PW3 consisted of

two steps: the development of the report and its deliv-

ery with a presentation. The report needed to contain

the business rules, system messages, and navigability

between screens; for each prototype, it was necessary

to make it clear which requirement was followed as a

basis; in addition to the need to add prints of all the

prototyped screens; and finally, to carry out valida-

tion with a Product Owner to detect inconsistencies

and problems in the requirements elicited. The sec-

ond step consisted of delivering the report and pre-

senting PW3 to the other colleagues.

The instruments used for this study were the ICF

and the questionnaire exploratory study. ICFs were

used, one for the learners and one for the teacher. The

elaboration of the questions for the research artifact

was inspired by the elements presented in Section 2.

The questionnaire was previously evaluated by three

PhD researchers and experts in Informatics in Educa-

tion, Computer Education, and HCI. This evaluation

was carried out to refine the information that could

be collected. Thus, corrections were made to some

questions to strengthen the learners’ responses about

the research question of this study.

The questionnaire used in the study consists of 21

questions, four of which are characterization ques-

tions and 17 questions based on the 3C’s of model

(Fuks et al., 2008). The questionnaire has closed

and open questions and different types of scales for

collecting learner feedback, such as the Likert scale

and the SAM scale (Self-Assessment Manikin (Lang,

1980)). We used the Likert scale to quantitatively

measure the learner’s perception and the SAM scale

to assess the learner’s feelings. For characteriza-

tion, information was collected, such as the course

the learners were enrolled in, gender, and how many

learners were present in PWs. For the communica-

tion dimension, three questions were collected based

on language, transmission, and categorization. For

the coordination dimension, eight questions were col-

lected based on topic, access, availability, roles, fre-

quency, addressing, and evaluation. For the coopera-

tion dimension, six questions were collected based on

registration and space configuration. The instruments

used in this study are available

1

.

About preparation and execution, before the

study was carried out, a presentation, in which they

were introduced to the study instruments and what

the learner’s participation in the study would consist

of. The presentation lasted around 15 minutes. Af-

ter the 31 learners who agreed to participate in the

study signed the ICF and received the questionnaire

in printed form. The learners answered the question-

naire during that class. It should be noted that the re-

1

https://figshare.com/s/150ebbda97d2f1ad8610

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

952

searcher was available to answer the learners’ doubts

about the questionnaire during the class. The teacher

also signed the ICF and was responsible for monitor-

ing the execution of the PWs.

About data analysis, the data obtained through

the exploratory study questionnaire was analyzed

quantitatively and qualitatively. The quantitative data

was analyzed using descriptive statistics (Lazar et al.,

2017). Before the qualitative analysis, the data was

cleaned, coded, and then organized. To code and or-

ganize the qualitative data, we followed the steps par-

tially of the Grounded Theory (GT) method (Corbin

and Strauss, 2014). GT has three stages in the cod-

ing process: open coding (1), axial coding (2), and

selective coding (3). In open coding (1), the data was

coded according to the answers given by each par-

ticipant. Subsequently, in axial coding (2), the codes

were grouped according to their properties and related

to each other, thus forming categories that represent

their characteristics. No selective coding was carried

out, as the intention was not to create a theory. The

open and axial coding stages were sufficient to under-

stand the LX, and 3C collaboration.

4 QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS

Some data was collected regarding the characteriza-

tion of the learners’ profiles. Regarding the course,

87% (N = 27) of the learners are enrolled in the CS

course, and 13% (N = 4) of the learners are enrolled

in the BI course. Regarding gender, it was noted that

81% (N = 25) are male and 19% (N = 6) are female.

About the number of learners who worked in groups,

68% (N = 21) worked in groups with 5 members, and

32% (N = 10) worked in groups with 6 members.

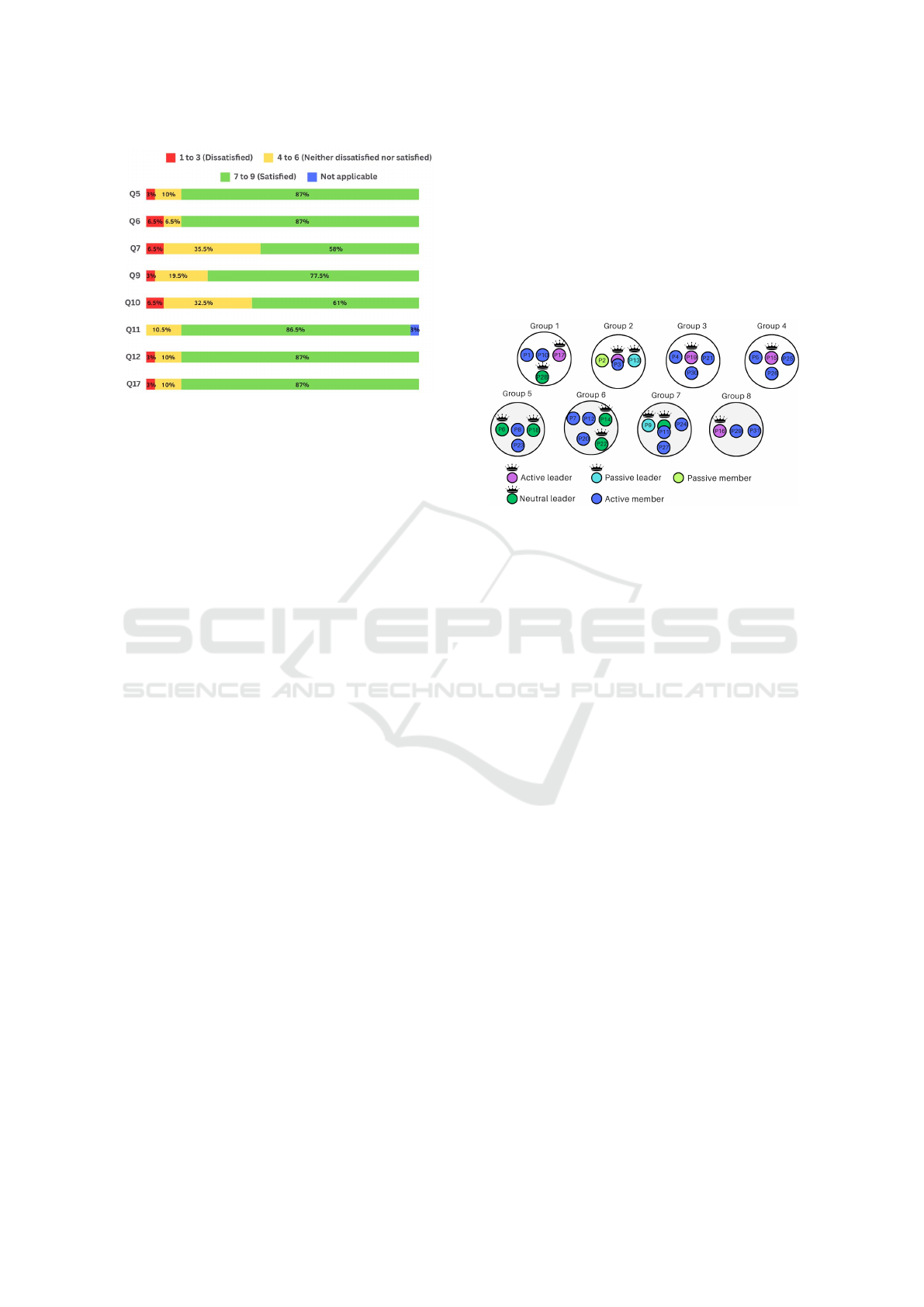

From the learners’ descriptions, it was possi-

ble to identify the groups formed to carry out the

PWs.Figure 1 shows the groups and their composi-

tion. The learners that participated in the study were

coded from P1 to P31. Non-study participants were

coded from NP1 to NP12. Learners who did not par-

ticipate in this study were only presented in Figure 1

to demonstrate group formations, however, no other

data from these learners is presented in this paper.

The exploratory study questionnaire has 17

questions to assess the three dimensions of 3C (Fuks

et al., 2008) and LX. Thus, three questions on com-

munication (Q2 to Q4), eight questions on coordina-

tion (Q5 to Q12), and six questions on cooperation

(Q1, Q13 to Q11) were developed. For this question-

naire, learners answered according to their percep-

tion and experience of developing PWs in groups, and

each learner could select more than one answer option

Figure 1: Group formation.

for each question. The results of the exploratory study

questionnaire are presented below.

Regarding the resources that learners used to com-

municate with group members (Q1), learners chose to

use WhatsApp

2

(37% | N = 26), Discord

3

(30% | N

= 21), Telegram

4

(6% | N = 4), E-mail (4% | N = 3),

Google Docs

5

(1% | N = 1), and C3SL Moodle

6

(1%

| N = 1). It is believed that WhatsApp and Discord

stood out as communication resources, as learners are

more familiar with them. Regarding the communi-

cation languages used by the learner to communicate

with the other members of the group (Q2), 44% (N

= 31) of the learners communicated by writing (text),

39% (N = 28) by speaking (audio), 14% (N = 10) pic-

torially (image) and 3% (N = 2) gesturally (video).

Regarding the learner’s communication with the

other members of the group (Q3), 53% (N = 19)

of the learners communicated continuously, and 47%

(N = 17) communicated punctually. Regarding how

the learner categorizes their communication with the

other members of the group (Q4), 42% (N = 25) of

the learners reported that it was of the inquiry type

(doubts, questions), 30% (N = 18) reported that it was

of the type of speech (affirmative and negative), 25%

(N = 25) reported that it was of the type of speech (di-

rect or indirect) and 3% (N = 2) reported that it was

of the type of emotions (happy, sad).

For Q5 to Q7, Q9 to Q12, and Q17, we used

emoticons from the SAM scale (Lang, 1980). To

better visualize the results, the SAM scale was orga-

nized into three points, where dissatisfied responses

are those marked to the left of the central column (1

to 3); neither dissatisfied nor satisfied responses are

those marked in the central column (4 to 6); and satis-

fied responses are those marked to the right of the cen-

tral column (7 to 9) (dos Santos et al., 2024). Thus,

Figure 2 shows the learners’ responses.

The results show significant satisfaction among

learners with 87% (N = 27) concerning the topics dis-

2

https://www.whatsapp.com

3

https://discord.com

4

https://web.telegram.org

5

https://docs.google.com

6

https://moodle.c3sl.ufpr.br

Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative Learning Context Using Computational Resources

953

Figure 2: Results of scale SAM.

cussed in the group (Q5) (Figure 2), the number of

members participating in the discussions and devel-

opment of the PWs (Q6) and the communication, dis-

cussions, and decisions made in the execution of the

PWs (Q12). This satisfaction among the learners was

believed to be due to the good friendships and part-

nerships they cultivated.

On the other hand, Figure 2 shows that 6.5% (N

= 2) of the learners were dissatisfied with the number

of members participating in the discussions and de-

velopment of the PWs (Q6), their availability for dis-

cussions and development of the PWs (Q7) and their

frequency of communication with the group for dis-

cussions and development of the PWs (Q10). It is be-

lieved that these learners declared themselves dissat-

isfied, as they could have participated more actively in

the group’s discussions and decision-making and ded-

icated themselves more to improving communication

frequency and rapport between group members.

Concerning the topics discussed in the group (Q5),

their role in the group (Q9), and their communica-

tion, discussions, and decisions made when carrying

out the PWs (Q12), Figure 2, shows dissatisfaction

among learners with 3% (N = 1). This learner called

himself an active leader, and it is believed that he was

dissatisfied because some members of his group were

not as dedicated as he was to carrying out the PWs.

Regarding the feeling that specific topics, activities,

and discussions are directed at the learner (Q11), 3%

(N = 1) of the learners reported that this did not apply.

It is believed that this learner was not present during

the group’s discussions and decision-making.

Regarding the learner’s perception of their role

in the group (Q8) (Figure 3), 55% (N = 18) of the

learners called themselves active members, i.e., they

were present in the group’s discussions and decision-

making. On the other hand, 6% (N = 2) of the learn-

ers called themselves passive members, i.e., they were

not always present in the group’s discussions and

decision-making. Concerning leadership, 18% (N =

6) called themselves neutral leaders, 6% (N = 2) pas-

sive leaders, and 15% (N = 5) active leaders. It is be-

lieved that all the groups had a learner as a leader, i.e.,

they had a learner who managed the group’s discus-

sions and decision-making. There was also more than

one learner per group, such as group two, where P13

declared himself a passive leader, and P3 declared

himself an active leader (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Results of Q8.

Regarding how the learners organized the execu-

tion of the PWs (Q13), 58% (N = 21) of the learners

divided the PWs topics among the group members,

33% (N = 12) of the group members worked simulta-

neously on all the PWs topics, 3% (N = 1) reviewed

the PW part done by a member of their group, 3% (N

= 1) reported that some PW topics were done individ-

ually, but others were done together, and 3% (N = 1)

reported that PW topics were shared and discussions

were also held. Most of the learners said that they

divided the PW topics between the group members,

as the PWs were large assignments and required ded-

ication to complete simultaneously. In addition, the

learners had demands from other subjects.

For Q14, a five-point Likert scale ranged from to-

tally disagree (1) to totally agree (5). Thus, regarding

the learner’s perception that the exchange of knowl-

edge between members helped in their knowledge ac-

quisition (Q14), 45% (N = 14) of the learners partially

agreed, 35% (N = 11) totally agreed, 16% (N = 5)

were neutral, and 3% (N = 1) partially disagreed. It

is believed that most learners were optimistic about

the exchange of knowledge between group members,

as this type of scenario provides a richer and more

dynamic experience and exchange of knowledge be-

tween learners and fosters and assists a greater under-

standing of the PWs subject.

To the learner’s self-perception of their profile

about their group (Q15), 13% (N = 4) of the learners

consider themselves to be more skilled than the other

group members, 6% (N = 2) consider more knowl-

edgeable than the other group members, 3% (N = 1)

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

954

consider unfamiliar with the subject of PWs concern-

ing the other group members, 3% (N = 1) consider to

be more patient about the other group members, and

the remaining 74% (N = 23) said that it does not ap-

ply. It is believed that most learners said that they do

not consider themselves to have more excellent skills

or knowledge than the other group members, as they

are at the same level of education.

11 collaborative techniques were used for PWs

in the learners’ perception (Q16). The brainstorm-

ing and interview stand out with 33% (N = 28) each.

These techniques were believed to be the most cited,

as they required more than one learner to carry out.

Moreover, other techniques were used, such as ex-

ploratory research (11% | N = 9), persona (7% | N

= 6), empathy mapping (5% | N = 4), storyboarding

(4% | N = 3), fly on the wall (2% | N = 2), question-

naires (2% | N = 2), storytelling (1% | N = 1), pro-

totyping (1% | N = 1), and body storm (1% | N = 1).

The last question sought to identify how learners felt

about PWs being sequential (Q17), shown in Figure

2. Thus, 87% (N = 27) of the learners felt satisfied,

10% (N = 3) were neutral, and 3% (N = 1) felt dissat-

isfied. The results show that most learners liked doing

the PWs gradually and sequentially.

5 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS

To carry out the qualitative analysis, the Atlas.ti tool

version 9

7

was used. Eight categories were created,

and the codes identified in this analysis are presented

below. For the category perception of PWs time

and number of members, learner P17 reported that

“many [learners] had little time” to carry out the

PWs, and P28 said that “I liked it, I had enough time

to develop the PWs”. Regarding the number of learn-

ers per group, P30 reported that there were “more

members than necessary” in his group. Analyzing the

learners’ comments and Figure 1, which presents the

learners’ grouping, it is noted that P30 (G3) was in a

group with six learners and had a leader. It is believed

that PWs with large groups generate greater dedica-

tion from the leader to manage the work of the mem-

bers, and possibly not all learners worked equally.

For the category perceptions about group inter-

action, P3 reported that “I wish the group had inter-

acted more. I stopped sending messages to encourage

and sending messages to talk about the PWs”. P3

also says that “I could not get everyone to collabo-

rate. Everyone is capable, they just need to make an

effort”. P3 considered himself an active leader. It is

7

https://atlasti.com/

the leader’s role to encourage the group to carry out

the PWs, but not all group members responded to this

motivation. In situations like this, it is suggested that

new motivation strategies be used in the group to ob-

tain more promising results.

For the category perceptions about the group’s

communication, P28 reported that “I believe I com-

municate well” making P28 “the group communi-

cated well”, and P17 also mentions that communica-

tion occurred “through a phone call”. However, P3

tells us that communication “at many times did not

exist” and also when there were discussions and con-

versations “[...] not everyone joined in” (P3). P6

says that communication was sometimes “delayed or

unresponsive”. From the accounts of communica-

tion between group members, it can be seen that there

were groups that were more closely knit and that there

was a group partnership. However, there were groups

where the members were not so closely knit or could

not communicate to develop the PWs. Communica-

tion is very important, as it provides the exchange of

information and knowledge between learners.

For the category perceptions about the organi-

zation of PWs, P3 reported that “one person did ev-

erything and the others [group members] only con-

sented”. In addition, P3 pointed out that “did some

topics that were the responsibility of others [mem-

bers], but I enjoyed doing them”. Another report from

P19 is that “the topics were divided up, most of them

were left to me (PW2 and PW3)”. Groups two and

three had some disagreements among the members

regarding the execution of the PWs. It is believed

that these conflicts occurred because the learners or-

ganized themselves in the distribution of the PW top-

ics, but not all followed through as planned. The PWs

organization is essential, as it helps to improve the

productivity of the group and also the quality of the

development of the PWs.

For the category perceptions about the role

played in the group, P28 pointed out that “the group

trusted me for the PW and that I contributed posi-

tively” in his group. P10 reported that “sometimes, to

get the team together, I had to take the initiative”. An-

alyzing the learners’ comments and Figure 1, which

shows the grouping of the learners, it can be seen that

P28 (G1) and P10 (G1) were in the same group. It is

believed that because these learners considered them-

selves leaders, they were responsible for taking the

initiative and managing the discussions and decisions.

As a result, the group became closer, as P28 points out

that “all [the learners] participated actively”. Hav-

ing a leader for the development of PWs is essential,

as it manages conflicts and also directs the work to be

developed for each member of the group.

Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative Learning Context Using Computational Resources

955

For the category negative perceptions about

PWs, P22 reported that “PW3 suffered from the end

of the period, but it was a rush” and P17 reaffirmed

that “the last [PW3] made me angry with some partic-

ipants”. Because of this, the learners pointed out that

the last PW suffered from the end of the semester. It is

believed that this PW overload occurred because the

other subjects the learners were studying were also

ending, and they probably had to hand in PWs and

other assessment activities. For the category positive

perceptions about the PWs, P28 reported that “I put

my knowledge into practice”, P19 says that “it was

very nice to develop the work and see the application

grow”, P30 says that it was the “first case of construc-

tive evaluation I have had in the course so far”, P5

says that “I liked the idea of it being the “same” work,

being continued”. An advantage of continuous PWs

is that learners can strengthen the knowledge base ac-

quired and put it into practice, in addition to seeing

the evolution of the acquired content.

For the category perceptions about the exchange

of knowledge, there were different reports, P3 com-

mented that “at many times there were no conversa-

tions or discussions about the topics”. Learner P28

said that he “liked it, the group was willing to an-

swer questions” from the other members, and P10

said that “sometimes I had questions and other par-

ticipants helped me”. P19 said that he had “a lot of

need to repeat instructions at different times to differ-

ent members”. It can be seen that the learners sought

out their group mates to exchange knowledge and dis-

cuss the PWs’ topics. The exchange of knowledge

can help learners develop critical thinking, in addition

to the development of social skills such as coopera-

tion. It can also stimulate the collective construction

of knowledge about specific content.

6 DISCUSSIONS

We would also like to emphasize some of the results

obtained in this study. We consider some strengths,

such as the communication language adopted by the

learners. It is believed that the type of language used,

including written and spoken conversations, and the

computing resources used, such as WhatsApp and

Discord, are in line with the learners’ experiences.

Another strong point is that some learners could de-

fine their roles in the group. It is believed that this

is a positive point, as the learners had the freedom

to choose their roles without interference from the

teacher or researchers. Furthermore, the learners

chose the role they felt most comfortable playing. An-

other positive point to consider is that PWs are contin-

uous. It is believed that this continuity of PWs meant

that the knowledge base acquired by the learners was

put into practice, allowing us to see the evolution of

the content acquired.

We identified the number of group members as a

weakness. Some learners were dissatisfied with the

number of members because the larger the group, the

greater the leader’s management work. It is believed

that even if all groups had a leader who guided, mo-

tivated, and managed the work of the other members,

not all members would embrace their role. Another

weakness is the frequency of communication between

group members. It is believed that even though the

leader played his role in the group through incentives,

guidance, motivation, and even work management,

the learners’ participation occurred unevenly.

We considered some difficulties, such as the fre-

quency and availability for discussions and develop-

ment of the PWs, since they occurred throughout the

course. This meant that the learners continually pro-

vided a certain amount of dedication of time. How-

ever, it occurred unevenly, with reports that there was

a lack of commitment from some learners. Another

difficulty was the dissatisfaction of some learners with

the role they played in the group. It is believed that

some learners assumed specific responsibilities and

sought an equal commitment from the other group

members, which in some situations didn not occur.

Based on some strengths, weaknesses, and diffi-

culties identified, we suggest that teachers adopt a

role exchange for learners in group PWs, allowing

more learners to acquire and put leadership skills into

practice. Another suggestion is closer supervision by

subject monitors and also by the teacher, about the

groups, to have faster and more accurate feedback

to assist learners in the weaknesses of group work.

Therefore, in answering the research question of this

study, the proposed objective was achieved. It was

possible to discover some weaknesses, needs, difficul-

ties, and strengths of the LX in a collaborative learn-

ing context. Furthermore, through the results identi-

fied in this study, it was felt necessary to continue in-

vestigating these topics since there is a lack of guide-

lines, instructions, and even support materials to assist

the teacher in collecting LX in a collaborative context.

7 CONCLUSION

The analysis of this exploratory study showed that

the LX was different for each learner regardless of

how many PWs were in a group. About the roles

played in a group, such as, one learner reported that

the group trusted him to develop the PWs. However,

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

956

another learner reported that he had to take the initia-

tive to bring the group together and also that he had

to develop PW topics that were not his responsibil-

ity, making him less satisfied with the development

of the PWs. Overall, this shows that we got differ-

ent accounts of experiences in a collaborative learning

context and also that we got different accounts from

members of the same group. It is believed that be-

cause three PWs were developed throughout the sub-

ject, some learners had more than one role in the

group. This is because the PWs required commit-

ment, dedication, willingness, and even the need to

deal with conflicts in the group.

Some limitations were identified for this ex-

ploratory study. One limitation may have been that

learners were given the freedom to form their groups.

We did not want to interfere in this group formation

process, but for the subsequent group formation for

other PWs, we suggest characterizing the participants

about the learner profiles to make the groups more

balanced. Another limitation is the selection of par-

ticipants, as it was carried out with RE learners, and

there was no representation of other academic sub-

jects. This may make it difficult to generalize the

results, as there is no diversity of perspectives and

experiences from different academics. Another lim-

itation is that elements external to the scenario may

have interfered with the results, such as noise in the

classroom (parallel conversations of colleagues) and

interruptions during the study’s execution. However,

based on the results, it was considered that the partic-

ipants fulfilled all the tasks requested in the study and

contributed to collecting LX in a collaborative context

using computer resources.

Finally, this study is expected to contribute to re-

searchers interested in LX assessment and collabora-

tive learning through the 3Cs of collaboration. In fu-

ture work, we intend to conduct a literature search to

verify and characterize technologies that support the

topics presented. The aim is to propose guidelines

and/or even improvements in a platform that supports

collaboration so that LX can be assessed effectively,

efficiently, and agilely. In addition, studies will be

conducted by considering a more varied sample of

learners and taking teachers into account.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would also like to thank the Coordination

for the Improvement of Higher Education Person-

nel (CAPES) - Program of Academic Excellence

(PROEX).

REFERENCES

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing

grounded theory. Sage publications.

dos Santos, G. C., Dos S. Silva, D. E., and C. Valentim,

N. M. (2023). Proposal and preliminary evaluation

of a learner experience evaluation model in informa-

tion systems. In Proceedings of the XIX Brazilian

Symposium on Information Systems, SBSI ’23, page

308–316, New York, NY, USA. Association for Com-

puting Machinery.

dos Santos, G. C., Silva, D. E., Peres, L. M., and Valentim,

N. M. C. (2024). Case study of a model that eval-

uates the learner experience with dicts. In Extended

Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems, CHI EA ’24, New York, NY,

USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

Fuks, H., Raposo, A., Gerosa, M. A., Pimentel, M., Fil-

ippo, D., and Lucena, C. (2008). Inter- and intra-

relationships between communication coordination

and cooperation in the scope of the 3c collabora-

tion model. In 2008 12th International Conference

on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design,

pages 148–153.

Huang, R., Spector, J. M., and Yang, J. (2019). Educational

Technology a Primer for the 21st Century. Springer.

Inaba, A., Supnithi, T., Ikeda, M., Mizoguchi, R., and Toy-

oda, J. (2000). How can we form effective collabora-

tive learning groups? In Gauthier, G., Frasson, C., and

VanLehn, K., editors, Intelligent Tutoring Systems,

pages 282–291, Berlin, Heidelberg. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Lang, P. (1980). Behavioral treatment and bio-behavioral

assessment: Computer applications. Technology in

mental health care delivery systems, pages 119–137.

Lazar, J., Feng, J. H., and Hochheiser, H. (2017). Re-

search methods in human-computer interaction. Mor-

gan Kaufmann.

Pimentel, M., Gerosa, M. A., Filippo, D., Raposo, A., Fuks,

H., and Lucena, C. J. P. d. (2006). Modelo 3c de

colaborac¸

˜

ao para o desenvolvimento de sistemas co-

laborativos. Anais do III Simp

´

osio Brasileiro de Sis-

temas Colaborativos, 2006(2006):58–67.

Schmidt, M. and Huang, R. (2022). Defining learning expe-

rience design: Voices from the field of learning design

& technology. TechTrends, 66(2):141–158.

Swedberg, R. (2020). Exploratory research. The production

of knowledge: Enhancing progress in social science,

2(1):17–41.

Torres, P. L. and Irala, E. A. F. (2014). Aprendizagem

colaborativa: teoria e pr

´

atica. Complexidade: redes

e conex

˜

oes na produc¸

˜

ao do conhecimento. Curitiba:

Senar, pages 61–93.

Zeichner, K. M. (2003). Formando professores reflexivos

para a educac¸

˜

ao centrada no aluno: possibilidades e

contradic¸

˜

oes. Formac¸

˜

ao de educadores: desafios e

perspectivas. S

˜

ao Paulo: UNESP, pages 35–55.

Exploratory Study on the Learner eXperience in a Collaborative Learning Context Using Computational Resources

957