Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in

Ubiquitous Conversational Data

Gabriel Valentim

1

, Jo

˜

ao Carlos D. Lima

1 a

, Fernando Barbosa

2 b

, Jo

˜

ao V

´

ıctor B. Marques

3 c

and Fabr

´

ıcio Andr

´

e Rubin

4 d

1

Centro de Tecnologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brazil

2

Reitora, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Brazil

3

Motorola Solutions, S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil

4

Petroleo Brasileiro S.A., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

{gabriel,caio}@inf.ufsm.br, Fernando.pires.barbosa@ufsm.br, joao.marques1@motorolasolutions.com,

Keywords:

Moral Harassment Detection, Ubiquitous Computing, Conversational Data Analysis, Artificial Intelligence,

Textual Similarity, Natural Language Processing (NLP), Mobile Computing, Workplace Harassment,

Pervasive Data Analysis, Ethical AI.

Abstract:

This study presents the development and evaluation of a moral harassment detection system focusing on mo-

bile and pervasive computing, leveraging artificial intelligence, textual similarity analysis, and ubiquitous data

generated from recorded audio. Implemented as a mobile application, the system allows users to record audio

and identify inappropriate behaviors using models like Mistral AI and Cohere, while integrating a collabora-

tive database that evolves with user contributions. Tests conducted ranged from simple phrases to complex

dialogues and colloquial expressions, demonstrating the hybrid approach’s effectiveness in capturing cultural

and linguistic nuances. By combining advanced technologies and user participation, the system adaptively

identifies moral harassment, enhancing detection accuracy and continuous learning. This work underscores

the potential of mobile devices and pervasive systems to monitor daily interactions in real-time, contributing to

moral harassment prevention, fostering ethical environments, and advancing the innovative use of ubiquitous

data for social well-being.

1 INTRODUCTION

The constant evolution of connectivity technologies,

including remote and wireless connections, has sig-

nificantly transformed the development and use of

ubiquitous devices, such as smart cards, sensors and

others. These devices permeate various areas of so-

ciety, playing fundamental roles in everyday life and

in the advancement of innovative technological solu-

tions (Barros, 2008).

Historically, computing has presented three major

trends that have shaped the relationship between users

and technologies. The first trend, known as main-

frame, is characterized by the “one computer, many

users“ model. Then, the era of personal comput-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9719-3205

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2044-312X

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3206-725X

d

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5154-7843

ers was consolidated with the concept of “one user,

one computer”. The third trend emerged with the

advancement of the Internet, highlighting the “one

user, many computers” paradigm. This last trend,

which aligns with distributed and mobile comput-

ing, is closely connected to the concept of Ubiqui-

tous Computing (Santos, 2014; Greenfield, 2018). In

this context, the presence of hundreds of computers

in a room, which might initially seem intimidating,

tends to become invisible to conscious perception,

just like the electrical wires hidden in the walls of

a room(Shaheed et al., 2015). Computing ubiquity

seeks to achieve this naturalness, integrating tech-

nology imperceptibly into everyday human activities

(Weiser, 1995).

Ubiquitous computing emphasizes the use of “in-

visible” tools, that is, devices that perform their func-

tions efficiently without demanding the user’s full at-

tention. Examples of this include glasses that, al-

though positioned on the face, do not divert the visual

680

Valentim, G., Lima, J. C. D., Barbosa, F., Marques, J. V. B. and Rubin, F. A.

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data.

DOI: 10.5220/0013478200003929

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 680-689

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

focus of the person using them, and audio capture de-

vices that can record conversations in hostile environ-

ments for later data analysis (Weiser, 1994).

Although such devices use different media —

such as sound, video, text and graphics — their pur-

pose is not to act as “multimedia devices”. Un-

like traditional multimedia machines, which require

the user’s direct attention, ubiquitous devices are de-

signed to disappear into the background, allowing

users to focus on essential tasks and interacting with

the environment (Weiser, 1995).

1.1 Problem

The increasing use of ubiquitous devices in everyday

environments has expanded the possibilities for mon-

itoring and analyzing human interactions, including

those that occur in adverse contexts, such as bullying

(Ahmed, 2024). Despite the significant advances pro-

vided by ubiquitous computing, there are still impor-

tant gaps to be explored to improve technologies for

detecting abusive behaviors, especially in the field of

Human-Computer Interaction (Blackwell et al., 2019;

Vranjes et al., 2020). This study seeks to investi-

gate how ubiquitous devices, particularly those based

on audio capture and data analysis, can be used to

identify harmful practices, such as bullying, during

technology-mediated interactions. Moral harassment,

characterized by abusive and repetitive behaviors that

affect a person’s psychological, social and/or physi-

cal integrity (DE SOUZA, 2018; Silva Junior et al.,

2024), can occur in various social environments, and

is especially worrying in the work and educational

context, where it compromises the well-being of in-

dividuals and destabilizes work and teaching environ-

ments.

1.2 Objective

This study aims to develop an intelligent system

for monitoring and accurately detecting situations

of moral harassment in data generated by Human-

Computer interaction, specifically by ubiquitous de-

vices in conversational environments. Using per-

vasive computing and natural language processing

(NLP) techniques, the system will analyze interac-

tions, focusing on identifying patterns of behavior

that may indicate harassment practices. The pro-

posal involves the development and implementation

of user-centered systems, integrated with portable de-

vices, such as smartphones, that efficiently capture

conversations, with the aim of providing a personal-

ized monitoring and detection experience.

The analysis will be conducted based on artificial

intelligence and machine learning methodologies, al-

lowing the identification, classification and provision

of feedback on the collected data, in order to iden-

tify moral harassment behaviors in an automated and

accurate manner.

1.2.1 Specific Objectives

The objective of this work is to develop an intelligent

system for detecting moral harassment in data gen-

erated by ubiquitous devices, specifically in conver-

sation environments mediated by Human-Computer

interaction. The main focus will be on the process-

ing and analysis of the captured audio data, using ad-

vanced Artificial Intelligence and machine learning

methodologies. To generate the audio, an application

will be created that will use the integrated microphone

of smartphones. This objective will be broken down

into the following goals:

1. Develop a system composed of two REST APIs

for the processing and analysis of audio data gen-

erated in Human-Computer interactions.

2. Implement a moral harassment detection using ar-

tificial intelligence widely available on the mar-

ket.

3. Create a detection based on SQL queries, using

pre-established data stored in the database.

4. Develop a detection method by similarity, com-

paring new data with information previously

stored in the database.

5. Implement a learning system based on user feed-

back to improve the detection of moral harass-

ment.

6. Analyze the characteristics of data generated by

ubiquitous devices, with emphasis on audio inter-

actions, to identify relevant variables in the detec-

tion of moral harassment.

7. Develop an application that works as a client for

capturing and recording audio files, allowing in-

teraction with the harassment detection system.

1.3 Justification

The growing adoption of pervasive computing tech-

nologies and the evolution of Human-Computer In-

teraction practices offer a unique opportunity to use

data generated by ubiquitous devices in an intelli-

gent and effective way. This data can be fundamental

to creating safer, more inclusive and respectful envi-

ronments, enabling, for example, the development of

user-centric systems capable of identifying harmful

behaviors, such as bullying. The implementation of

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data

681

a machine learning-based solution to detect such be-

haviors is a significant innovation, with the potential

to promote a positive impact on society by providing

a healthier environment, both in professional and ed-

ucational contexts.

Bullying, especially in higher education institu-

tions, is a phenomenon that, despite its significant

repercussions, still does not receive the attention it

deserves in the academic literature. Characterized by

abusive and repetitive practices, with the aim of hu-

miliating and psychologically destabilizing the vic-

tim, bullying can result in devastating impacts, both

in the personal lives of those involved and in the work

environment and in the educational context. In the

educational context, bullying compromises the well-

being of teachers and students, harming organiza-

tional dynamics and directly affecting productivity

and the quality of teaching. Therefore, it is essen-

tial that bullying in educational institutions be dis-

cussed in more depth, with the exploration of tech-

nological solutions for its detection and prevention

(DE SOUZA, 2018).

2 METHODOLOGY

The methodology adopted for this research follows

a practical and applied approach, with an empha-

sis on Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and User-

Centered Systems. The main focus is the develop-

ment of a mobile application aimed at detecting bul-

lying in audio-based interactions generated by ubiqui-

tous devices. The process involves creating a mobile

application using TypeScript, React Native and Expo

technologies, allowing the recording and sending of

audio data for later analysis. The backend system will

consist of two REST APIs: one built with TypeScript

and Nest.js and another with Python, for processing

and analyzing the captured data.

2.1 Procedures and Resources

This section details the procedures adopted for the de-

velopment of the application and the analysis system,

as well as the technological resources employed. The

process of detecting moral harassment is centered on

user-device interactions, with the objective of iden-

tifying abusive behaviors through the analysis of au-

dio recordings made by users. The focus is on under-

standing and interpreting communication patterns that

may indicate moral harassment, considering the dy-

namics of human-computer interaction and how ubiq-

uitous devices can be used in an invisible but effective

way to monitor and detect inappropriate behaviors.

2.1.1 System Development

The development of the system was designed to han-

dle ubiquitous data in audio format, aligning with

the principles of pervasive computing and Human-

Computer Interaction (HCI). The application backend

consists of two REST APIs, each playing a specific

role in data processing and analysis:

1. API 1: Developed in TypeScript using the Nest.js

framework, in conjunction with Prisma ORM, en-

suring a robust structure for data management and

integration with the PostgreSQL database.

2. API 2: Implemented in Python with the FastAPI

library, focused on audio processing and more

complex analyses, including integration with ma-

chine learning models.

The client responsible for data collection, that is,

recording conversations that will generate audio for

analysis, will be developed as a mobile application

using TypeScript, React Native and Expo technolo-

gies. The interface of this application will be designed

based on the principles of User-Centered Systems, en-

suring ease of use and a user-friendly experience dur-

ing interaction.

3 BACKGROUND AND RELATED

WORK

3.1 Human-Computer Interaction

(HCI)

For users to get the most out of a system, interfaces

need to be designed to promote efficient and intuitive

interaction. This requires that interfaces meet criteria

of usability, user experience, accessibility, and com-

municability (Santos, 2014; Ramirez et al., 2022).

Usability refers to the ease with which users learn

to use the system and perform their tasks. It is a set of

factors that measures the quality of the user’s interac-

tion with the system. These factors include: ease of

learning, memorization, efficiency, safety during use,

and user satisfaction when completing their activities

(Santos, 2014).

User experience focuses on the emotions and sen-

sations generated by the interaction with the system.

Although often associated with user satisfaction, it

goes beyond that, considering how the system impacts

the perception and comfort of those who use it (Jun

et al., 2008; Santos, 2014; Alhirabi et al., 2021).

Accessibility, in turn, concerns the system’s abil-

ity to remove barriers that limit use by people with

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

682

different abilities. By ensuring accessibility, it be-

comes possible to expand the reach of the software

to more diverse audiences. A clear example is the use

of screen readers, which help people with visual im-

pairments to interact efficiently (Santos, 2014).

Finally, communicability addresses how the sys-

tem’s design communicates its operating logic to

users. When the user understands the logic behind

an interface, they are more likely to use it creatively

and effectively. An example of this is the application

of visual analogies that refer to objects in the physical

world, facilitating familiarity with the system (Santos,

2014).

3.1.1 HCI in Ubiquitous Systems

Ubiquitous computing represents a natural evolution

of computing, where the interaction between users

and technological devices occurs in an integrated and

continuous manner. This approach seeks to create en-

vironments full of intelligent devices that focus on im-

proving the human experience, often without the need

for explicit user intervention (Stefanidi et al., 2023).

Interaction in ubiquitous systems goes beyond tra-

ditional interfaces and includes implicit interaction

methods. This means that systems can capture user

input data automatically and naturally, without requir-

ing direct attention. A classic example is that of au-

tomatic doors that detect the presence of a person and

open. Although implicit, this interaction is the re-

sult of a system that interprets data from the environ-

ment and responds to human behavior (Vallejo-Correa

et al., 2021).

To ensure an effective experience, ubiquitous sys-

tems must adopt more natural interfaces that simplify

interaction. Technologies such as voice commands,

gestures and touch screens are examples of solutions

that replace or complement traditional graphical inter-

action elements. These technologies also help to sub-

tly integrate computational elements with the physical

environment, creating a homogeneous and natural ex-

perience for the user (Santos, 2014).

However, the development of ubiquitous systems

brings significant challenges. Among them are:

• The complexity of implementing and evaluating

systems in real scenarios.

• The need to collect and store continuous interac-

tion data without compromising the user experi-

ence.

• The difficulty of dealing with tasks that can be

paused, resumed or shared between users.

• The challenge of accurately identifying the user’s

context, given its unpredictability and environ-

mental variables.

These challenges are even more evident in sys-

tems such as the one proposed in this work, which

seeks to detect moral harassment. The idea of main-

taining discreet audio sensors, handling multiple par-

ticipants, and interpreting conversations in real time

requires innovative solutions. Furthermore, determin-

ing the intent or context of a conversation represents

a significant technical and ethical hurdle.

Ubiquitous computing radically transforms the re-

lationship between humans and machines. By spread-

ing computational services across all aspects of daily

life, it expands the possibilities for interaction. How-

ever, the success of this transformation depends on

projects that prioritize HCI principles, ensuring that

applications are intuitive, accessible, and effective for

their users (Santos, 2014).

3.2 Moral Harassment

Moral harassment is characterized as any abusive,

repetitive and systematic behavior that affects a per-

son’s psychological, social or physical integrity, com-

promising their dignity, threatening their employment

relationship and disrupting the work environment.

This type of behavior is generally manifested by su-

periors in relation to their subordinates, using their

position of power to commit such abuse. Harassment

can be explicit or implicit.

In the implicit form, the harasser resorts to non-

verbal behavior, such as indifference or irony, which

are more difficult to prove. This approach allows the

aggressor to deny his intentions if confronted, mask-

ing the abusive behavior. In the explicit form, the ac-

tions become evident not only to the victim, but also

to third parties. Examples include excluding the vic-

tim from activities or groups without justification, ex-

posing them to embarrassing situations in front of col-

leagues, or publicly belittling their work. This type of

practice, which is more serious, highlights the perver-

sity of the harasser (DE SOUZA, 2018).

The harasser’s main objective is to subjugate the

victim, shaking their self-esteem and exerting con-

trol over them, often in a callous and destructive way.

Men, for example, may be attacked in relation to their

virility, while women often face intimidation that re-

inforces stereotypes of submission. This perverse

practice reflects the aggressor’s unlimited need to as-

sert his power, regardless of the consequences for the

victim (DE SOUZA, 2018).

The victim, in turn, often chooses to remain silent,

fearing reprisals or the loss of their job. This toler-

ant behavior, although understandable, contributes to

the perpetuation of the cycle of abuse. Continuous

humiliation can have serious impacts on the identity,

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data

683

dignity and emotional health of the person being ha-

rassed, compromising both their personal and profes-

sional life. In addition, it directly affects their work

capacity and general well-being (DE SOUZA, 2018).

Moral harassment in the academic environment,

especially in higher education institutions, presents

specific nuances. Although it is a relevant problem,

it still lacks in-depth discussion in the literature. In

these institutions, harassment can occur both between

professors and students and between colleagues, gen-

erating negative consequences for the well-being of

those involved, the quality of teaching and the or-

ganizational dynamics. In some cases, students can

also act as agents of harassment, adopting disrespect-

ful attitudes towards professors, who often choose not

to report such incidents to avoid conflicts or harm to

their careers (Da Silva Franqueira et al., 2024).

Ubiquitous computing emerges as a potential ally

in detecting moral harassment, regardless of the envi-

ronment in which it occurs. Since many of these prac-

tices involve verbal interactions or behaviors, smart

devices can be used to monitor and record these

events. For example, audio sensors attached to cor-

porate or academic environments could capture sus-

picious conversations and send them to systems that

assess the possibility of bullying. Similarly, devices

that capture videos or other forms of interaction could

provide concrete evidence for the analysis of inappro-

priate behavior.

Companies equipped with ubiquitous technology

and monitored classrooms can not only prevent inci-

dents of harassment, but also ensure greater safety and

justice by providing reliable data that corroborates or

refutes complaints. These innovations have the poten-

tial to transform the way harassment cases are iden-

tified, reported and treated, contributing to healthier

and more equitable environments.

3.3 Moral Harassment Detection

Moral harassment detection is a challenge that re-

quires the integration of several technologies, such

as artificial intelligence, natural language processing

and ubiquitous computing, to create a system capa-

ble of identifying patterns of abusive behavior. This

project proposes an innovative solution that uses au-

dio recordings as input for a system composed of in-

terconnected APIs, artificial intelligence models, and

textual analysis techniques. The goal is to offer a

practical and efficient tool to identify and classify

possible occurrences of moral harassment in different

contexts.

4 DEVELOPMENT

4.1 Architecture

The system architecture is based on APIs that com-

municate to detect moral harassment from received

audios. The mobile application, developed with a fo-

cus on system testing, uses the cell phone’s micro-

phone to capture conversations. The general flow of

the system is described below.

The application’s database was filled with several

phrases considered examples of moral harassment. In

a real scenario, this table could contain a much larger

volume of records, which would justify a later analy-

sis to optimize this approach.

Initially, the application records a conversation be-

tween the participants using the cell phone’s micro-

phone. The audio is then sent to the detection system,

with communication between the application and the

backend being carried out through an API developed

in Nest.js. The backend stores the audio in the file

system and uses an executable program in Python,

with the Whisper library, to convert the audio into

text. From the generated text, the system performs

four analysis steps:

1. Database query: The Nest.js API performs an

SQL query to compare the generated text with

phrases previously entered in the database.

2. Similarity analysis: The generated text is sent to

a Python API, which performs a similarity search

in the database, returning the result to the Nest.js

API.

3. Mistral Detection: The text is analyzed by an API

that uses the Mistral artificial intelligence model,

returning a detailed analysis to the Nest.js API.

4. Cohere Detection: Similar to the previous step,

but using the Cohere model, the analysis is re-

turned to the Nest.js API.

After these analyses, the results are stored in the

database and sent to the application, allowing the user

to view the detailed data. The complete architecture

of the flow is presented in Figure 1.

In the case of detection based on a database with-

out similarity, the identification of moral harassment

is attributed as a decision by the “Administrator”,

without implying a definitive or punitive nature. If the

database does not detect harassment, users can vote

on whether or not they consider the text to be moral

harassment. The votes generate a result that can be

positive, negative or undetermined, depending on the

consensus or tie between the votes. This process al-

lows the system to evolve by incorporating the collec-

tive perception of users.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

684

Figure 1: Project architecture mind map.

The detections performed by the Mistral and Co-

here AI models are immutable by users, since the

models are trained and maintained by specialized

companies. Similarity detection, in turn, uses the

same database as the detection without similarity, be-

ing updated jointly, which eliminates the need for a

separate voting system for this stage.

In this way, the proposed solution combines tradi-

tional and advanced textual analysis techniques, tak-

ing advantage of both collective intelligence and the

precision of modern artificial intelligence models.

4.1.1 Application

The mobile application developed for this project

plays an essential role in allowing the user to inter-

act with the moral harassment detection system. It

was designed to be intuitive and functional, offering

a practical experience for recording audio and con-

sulting analysis results. The application has an inter-

face organized into different screens, each with spe-

cific functionalities to meet the system flow.

4.1.2 Home Screen

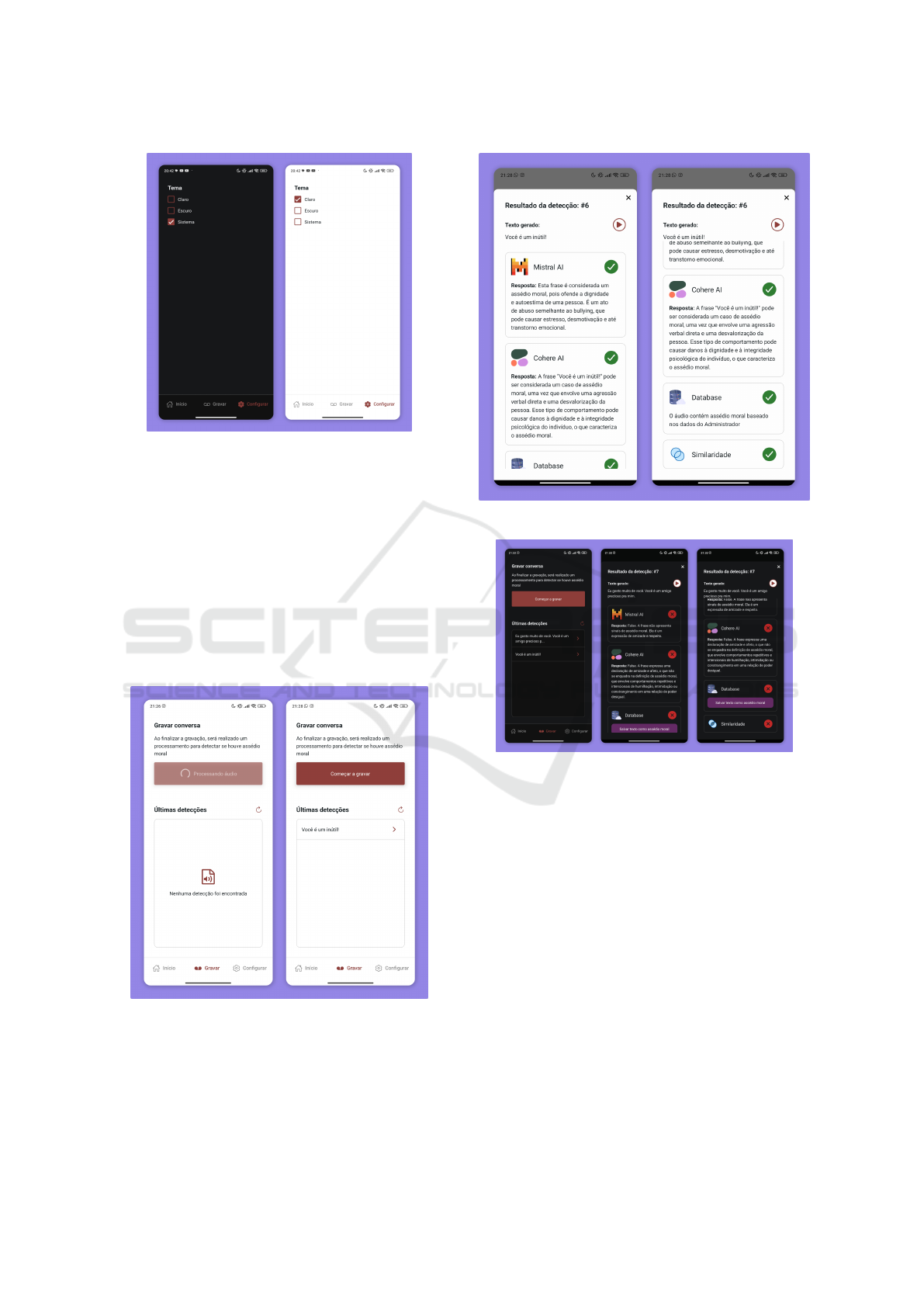

The application’s home screen (Figure 2) is the start-

ing point for the user. It presents the application’s ob-

jective through a clean and straightforward interface,

with a link that leads to the main functionality, which

is present on the recording screen.

4.1.3 Recording and Detection Screen

The recording and detection screen (Figure 3) is

where the user’s main interaction with the system oc-

curs. Here, the user can start or stop recording audio

using a centralized button. After recording, the audio

Figure 2: Application Home Screen.

Figure 3: Recording and detection screen.

is automatically sent to the detection system for anal-

ysis. During the process, the screen displays a pro-

cessing indicator to inform the user that the analysis

is in progress. In addition, the analysis results can be

presented directly on this screen, allowing for quick

and efficient viewing.

4.1.4 Settings Screen

The settings screen (Figure 4) offers options to cus-

tomize how the application works. On this screen, the

user can adjust only the application’s theme, switch-

ing between light, dark or system-based mode.

4.2 Using the Detection System

The bullying detection system was subjected to a se-

ries of tests that explored different scenarios, from

simple sentences to more complex interactions. The

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data

685

Figure 4: Settings screen.

objective of these tests was to evaluate the effective-

ness of the system in identifying bullying and its abil-

ity to learn and adapt based on user interactions.

Initially, a simple and offensive sentence, “You are

useless”, was recorded and analyzed. The result re-

vealed that all four evaluators involved considered the

sentence to be bullying, as shown in Figure 5. This

result demonstrates that, even using short sentences

previously recorded in the database, the system is ca-

pable of accurately identifying harassment situations.

Figure 6 shows the results generated by the system for

this test.

Figure 5: First Recording.

In the second test, a common phrase containing

compliments without any aggressive connotation was

used. The evaluators did not consider the phrase

as moral harassment, which confirms the system’s

Figure 6: Results of the first recording.

Figure 7: Second Recording.

ability to differentiate harmless interactions from po-

tentially abusive situations. Figure 7 illustrates the

recording process and the results of this test.

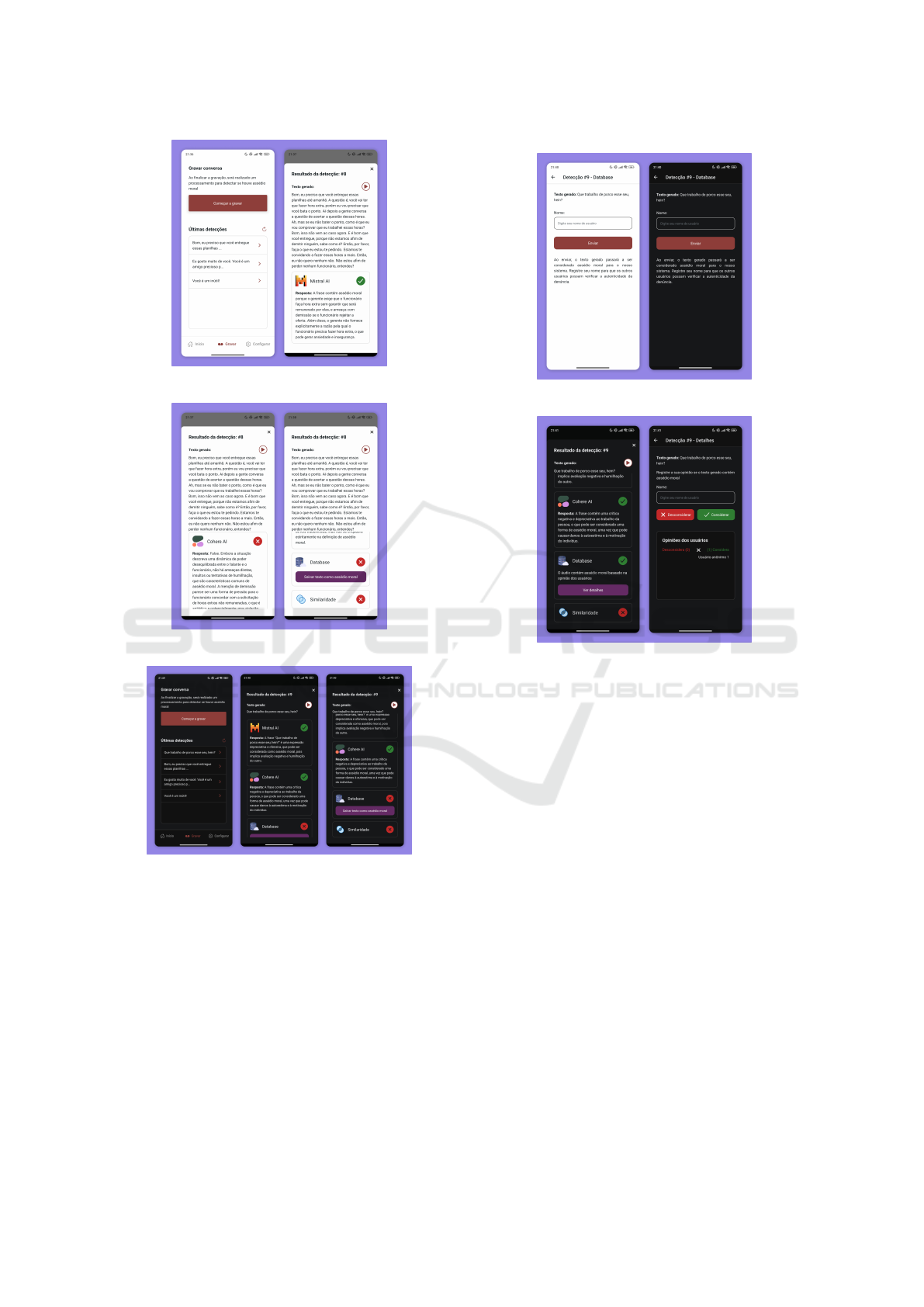

In the third test, two participants simulated a pro-

fessional conversation in which a superior employee

delegated tasks to a subordinate. The analysis re-

vealed that the Mistral AI model considered the inter-

action to be bullying (Figure 8). However, the Cohere

model did not classify the conversation as bullying,

although it did identify unethical behavior and possi-

ble violations of labor laws (Figure 9). Furthermore,

database queries and similarity methods also did not

detect bullying in this scenario, highlighting the nu-

ances involved in interpreting complex interactions.

The fourth and final test explored the user voting

functionality. A sentence with regional characteris-

tics and slang was submitted to the system. Although

the artificial intelligence detected moral harassment,

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

686

Figure 8: Third Recording and Results.

Figure 9: Third recording and more results.

Figure 10: Fourth recording and results.

database queries and similarity methods were not ef-

fective. Figure 10 illustrates the recording process

and the initial test results.

It is possible to observe in Figure 10 that the

database evaluation did not detect moral harassment,

but it is possible to save the text if the user considers

it to be moral harassment, when doing so a screen to

save is displayed, which is represented by Figure 11.

An audio in which moral harassment was not de-

tected by the administrator (database) allows the user

to save this detection as moral harassment if they

consider it, this opens a vote where the application

users can leave their vote on whether that conversa-

Figure 11: Fourth recording and more results.

Figure 12: Voting for fourth recording.

tion contains moral harassment or not. This can be

seen in Figure 12, where the first screen shows the ha-

rassment detection by the user and the second screen

shows how the vote for that text is going.

As seen in Figure 12, users can vote on whether

or not moral harassment exists in the sentence. In

cases of a tie, the detection result is considered un-

determined (Figure 13). When the majority of votes

do not consider the interaction as moral harassment,

the system alerts that no moral harassment was iden-

tified, as shown in Figure 14.

A final possible case is the vote where the ma-

jority of users do not consider the text as moral ha-

rassment, this causes the detection results to alert that

it was not considered moral harassment based on the

users’ opinion. Figure 14 shows the vote where the

majority does not consider moral harassment and how

this is displayed on the screen.

The fourth test shows how the system can learn

from users. In addition to being able to detect using

highly intelligent services such as two artificial intel-

ligences, it is also possible to improve the basis of the

moral harassment detection system itself.

This system can be integrated with other devices

that are considered more pervasive and thus detect ir-

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data

687

Figure 13: Tie of a vote.

Figure 14: They disregard the presence of moral harass-

ment.

regularities in everyday conversations. The applica-

tion developed was designed mainly to test this sys-

tem and provide the possibility for users of the appli-

cation to improve the system based on their opinions.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The presented bullying detection system demon-

strated significant potential in identifying inappropri-

ate behaviors in work and everyday contexts. Using a

hybrid approach that combines artificial intelligence,

textual similarity analysis, database and collaborative

user voting, the system proved to be an adaptable

tool with continuous learning capacity. The tests per-

formed demonstrated the effectiveness of the system

in dealing with different scenarios, from simple sen-

tences to more complex dialogues, and highlighted its

versatility in integrating various detection methods,

such as the Mistral AI and Cohere models.

Despite the contributions, challenges were identi-

fied that can be explored in future work. Firstly, the

analysis of long and complex conversations revealed

limitations in processing, especially due to the delay

associated with converting audio to text and the large

number of words analyzed by the database. In addi-

tion, the system depends on explicit user interaction

to start and end recordings, which limits its perva-

siveness. Ubiquitous devices equipped with sensors

that automatically capture conversations could make

the system more integrated into the environment, but

they raise ethical issues and technical challenges re-

lated to real-time data detection and storage.

Another relevant limitation is the database used

for text comparison. In a real scenario, a significantly

larger and more diverse database would be required,

which would generate new challenges, such as vali-

dating the authenticity of the inserted sentences and

managing the impact of the increase in data on the

system’s performance.

In summary, this work validates the technical fea-

sibility of a system for detecting moral harassment

and highlights the potential of mobile and pervasive

computing technologies in promoting more ethical

and respectful social and work environments. At the

same time, it points out ways to develop more robust

and integrated solutions, reinforcing the importance

of approaching the topic from an interdisciplinary

perspective that unites technology, ethics and social

well-being.

6 FUTURE WORKS

Recommendations for Future Works:

• Ethics in Ubiquitous Devices. Investigate the

ethical and social implications of devices that cap-

ture conversations continuously, considering the

privacy and consent of individuals.

• Development of Ubiquitous Systems. Design

a pervasive device that uses systems similar to

the one developed, capable of operating au-

tonomously and effectively in different environ-

ments, minimizing the need for direct user inter-

action.

• Optimization and Scalability. Implement op-

timization techniques for processing long audio

files and managing large volumes of data based

on phrases, ensuring greater speed and efficiency

in detection.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

688

6.1 Ethical and Privacy Considerations

The implementation of a system for detecting moral

harassment in ubiquitous conversations raises signif-

icant challenges in terms of privacy and ethics. To

address the ethical and privacy challenges associated

with this paper, several measures should be imple-

mented in future works:

• Informed Consent. The system should not

record audio without the user’s explicit consent.

Before any recording, a clear notice should be dis-

played explaining the purpose of audio capture

and requesting permission. Additionally, users

should be able to stop the recording at any time.

• Anonymization and Data Protection. All cap-

tured audio should be automatically converted

into text before processing, and any identified sen-

sitive information should be anonymized or re-

moved through automatic filters.

• Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence. The

system’s detections should be used only as an

indicative and should not have punitive implica-

tions, always requiring human review to prevent

false accusations.

• Right to Be Forgotten and User Control. The

system should allow users to request the deletion

of their recorded interactions. Moreover, stored

data should be encrypted and accessible only to

authorized users, preventing misuse by third par-

ties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank UFSM/FATEC/MEC

for partially funding this work through project

3.01.0076 (100749), 952041/2023 - MEC /

23081.156610/2023-12.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, R. (2024). Cyber harassment in the digital age:

Trends, challenges, and countermeasures. Preprints.

Alhirabi, N., Rana, O., and Perera, C. (2021). Security and

privacy requirements for the internet of things: A sur-

vey. ACM Transactions on Internet of Things, 2:1–37.

Barros, P. H. L. (2008). Uma proposta para sincronizac¸

˜

ao

de dados em dispositivos ub

´

ıquos. Trabalho de Con-

clus

˜

ao de Curso (Graduac¸

˜

ao).

Blackwell, L., Ellison, N., Elliott-Deflo, N., and Schwartz,

R. (2019). Harassment in social virtual reality: Chal-

lenges for platform governance. Proceedings of the

ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3:1–25.

Da Silva Franqueira, A. et al. (2024). Ass

´

edio moral nas

instituic¸

˜

oes n

˜

ao escolares.

DE SOUZA, E. S. (2018). O ass

´

edio moral nas empresas.

Greenfield, A. (2018). Radical Technologies: The Design

of Everyday Life. Verso.

Jun, E., Liao, H., Savoy, A., Zeng, L., and Salvendy, G.

(2008). The design of future things, by d. a. norman,

basic books, new york, ny, usa. Human Factors and

Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries -

HUM FACTORS ERGONOM MANUF SER, 18:480–

481.

Ramirez, G., M

´

endez, Y., Mill

´

an, A., Gonz

´

alez, C., and

Moreira, F. (2022). HCI 2020 Master’s Degree Study:

A Review, pages 91–103.

Santos, R. M. (2014). Caracter

´

ısticas e medidas de software

para avaliac¸

˜

ao da qualidade da interac¸

˜

ao humano-

computador em sistemas ub

´

ıquos.

Shaheed, S., Abbas, J., Shabbir, A., and Khalid, F. (2015).

Solving the challenges of pervasive computing. Jour-

nal of Computer and Communications, 3:41–50.

Silva Junior, D., Pereira, R., and Baranauskas, M. C. (2024).

Raising awareness on bullying through a design situa-

tion and rationale.

Stefanidi, E., Bentvelzen, M., Wo

´

zniak, P., Kosch, T.,

Wo

´

zniak, M., Mildner, T., Schneegaß, S., M

¨

uller, H.,

and Niess, J. (2023). Literature reviews in hci: A re-

view of reviews.

Vallejo-Correa, P., Monsalve-Pulido, J., and Tabares-

Betancur, M. (2021). A systematic mapping review

of context-aware analysis and its approach to mobile

learning and ubiquitous learning processes. Computer

Science Review, 39:100335.

Vranjes, I., Farley, S., and Baillien, E. (2020). Harassment

in the Digital World: Cyberbullying, pages 409–433.

CRC Press.

Weiser, M. (1994). The world is not a desktop. Interactions,

1(1).

Weiser, M. (1995). The computer for the 21st century:

specialized elements of hardware and software, con-

nected by wires, radio waves and infrared, will be so

ubiquitous that no one will notice their presence. In

Readings in Human–Computer Interaction. Morgan

Kaufmann.

Development of a Solution for Identifying Moral Harassment in Ubiquitous Conversational Data

689