The Role of Gender and Clear Communication in Digital Health

Engagement for Blood Clot Management

Ionel Ros¸u

1 a

, Petru Kallay

2 b

and Tudor Dan Mihoc

3 c

1

S

¨

odersjukhuset, Sjukhusbacken 10, 118 83 Stockholm, Sweden

2

Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Babes¸ Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

3

Center for the Study of Complexity, Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, Babes¸-Bolyai University,

Cluj Napoca, Romania

Keywords:

Blood Clot, Digital Health, Gender Perspective, Elderly Patients, Communication.

Abstract:

This study examines factors influencing older patients’ use of the Internet to access health-related information,

focusing on gender differences and the clarity of information provided by emergency units about anticoagulant

treatment and blood clot management. Data were collected from respondents aged 60+ through a survey, with

responses weighted to align with population demographics. Statistic methods and regressions were employed

to analyze the data. The results indicate that gender significantly predicts Internet use, along with the clarity

of emergency service offerings. However, reverse analysis suggests that Internet usage does not significantly

improve patient understanding of emergency unit support.

1 INTRODUCTION

A significant challenge in contemporary society is to

seek the availability of high-quality information, par-

ticularly with regard to healthcare matters. Although

young people apparently find the process of searching

for information from online sources easy, older gen-

erations face challenges in this endeavor. The amount

of poor-quality information available online is very

large, making the process of selecting trustworthy and

correct information extremely difficult.

Human-computer interaction is critical in this con-

text today. The risks associated with oral anticoag-

ulant therapy increase with age (Torn et al., 2005),

which highlights the need for comprehensive infor-

mation to ensure effective treatment management

(Kagansky et al., 2004).

Consequently, a question arises naturally: How ef-

fective is the communication and information sharing

process between healthcare providers and elderly pa-

tients on anticoagulant treatment and blood clot man-

agement, and what role can digital platforms play in

improving patient understanding and patient satisfac-

tion with health care?

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4820-1609

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-3839-4757

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2693-1148

In order to address these topics, we define the re-

search questions as follows:

⋆ To what extent does gender affect the likelihood

that older patients will use digital resources to

supplement their understanding of anticoagulant

treatment and blood clot management?

⋆ How does the clarity of information provided by

the emergency unit about anticoagulant treatment

and blood clot management influence the use of

the Internet to search for information about one’s

condition and medication in connection with the

illness?

Conducting a survey might help fill in some of the

gaps in our understanding and get different perspec-

tives on this issue based on age.

To obtain answers to these questions, we con-

ducted a survey among patients receiving anticoag-

ulant treatment in the Blekinge region.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Research suggests that effective communication be-

tween healthcare providers and patients about anti-

coagulant treatment can be improved through digi-

tal platforms and multimedia interventions. Although

Ro¸su, I., Kallay, P. and Mihoc, T. D.

The Role of Gender and Clear Communication in Digital Health Engagement for Blood Clot Management.

DOI: 10.5220/0013484300003938

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 377-384

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

377

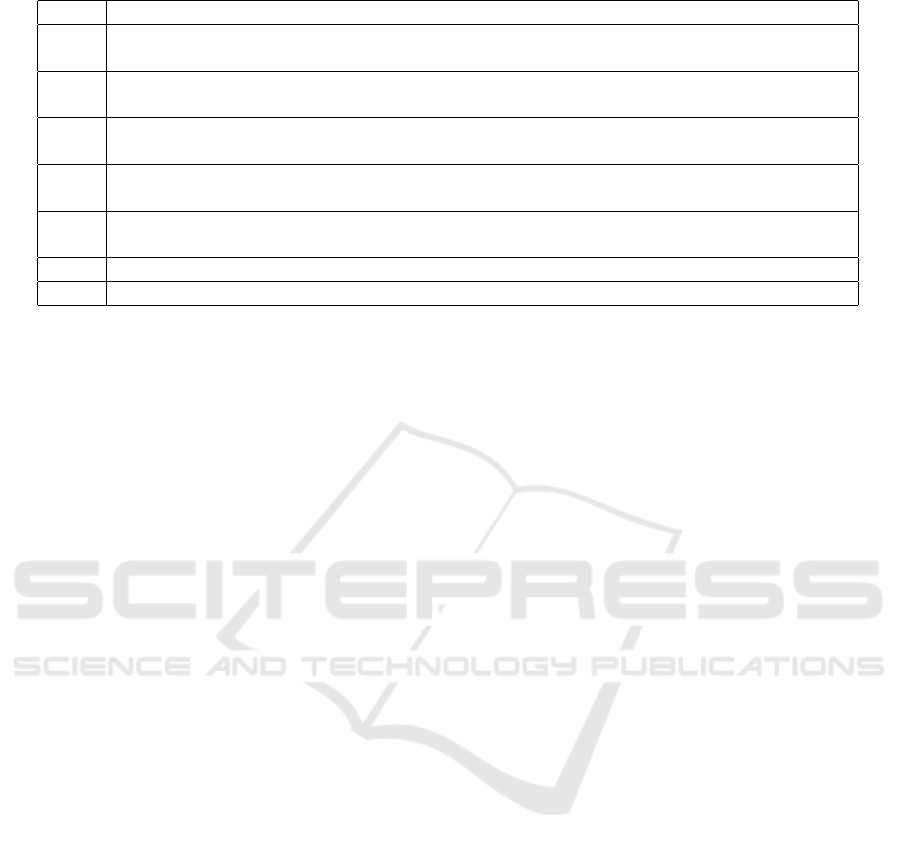

Table 1: Survey Questions.

Q1 Please specify your gender. Choice of male, female, or I prefer not to answer.

Q2 What is the age group to which you belong?

Choices: 18 − 39; 40 − 59; 60 − 79; 80+

Q3 Did you use the internet to search for information about your condition and medications in

relation to your illness?

Q4 After you left the hospital, did you receive information from a nurse about blood-thinning

treatment?

Q5 Have you received an information brochure about the emergency unit and one brochure

about the medication?

Q6 Did you think the written information about the emergency unit was a good support in your

treatment?

Q7 What pages/sources?

Q8 Is it clear to you as a patient what the emergency unit can offer you for support?

traditional methods remain effective, multimedia ap-

proaches can improve patient knowledge and save

healthcare professionals’ time (Sim and Galbraith,

2020). Visual aids, such as digitized color menus for

warfarin pills, have been shown to increase patient-

provider concordance, particularly in patients with

communication barriers (Schillinger et al., 2006). Pa-

tients, especially young people who have been a short

time since starting therapy, express interest in us-

ing mobile devices to collect information to support

the treatment of anticoagulant therapy (Olomu et al.,

2014). However, barriers to optimal patient educa-

tion include limited time with providers and a lack of

coordinated treatment management programs (Wang

et al., 2022).

Although seniors use the Internet to learn about

diseases, medications, treatments, and healthy living

(Waterworth and Honey, 2018), barriers such as low

trust, financial restrictions, lack of familiarity with

the Internet, and low health literacy can hinder their

access. However, research shows that customized

online medical databases can significantly improve

older adults’ health-related knowledge (Freund et al.,

2017). These findings suggest that older adults are

willing to use technology for the acquisition of health

information when provided with the appropriate tools.

According to (Fischer et al., 2014), older adults

approach online health information differently than

younger adults, with adoption rates increasing but

with some obstacles still present; barriers to technol-

ogy adoption include issues with familiarity, trust, and

privacy.

A study (Bujnowska-Fedak and Mastalerz-Migas,

2015) reveals that face-to-face interactions with

healthcare professionals remain the preferred source

of health information for older adults, with only

32% opting for the Internet for documentation. This

study also emphasizes other influence factors, such

as gender, education, living situation, or self-assessed

health. Several strategies adapted to the needs of the

elderly are proposed to address these challenges in

(Marschollek et al., 2007), with an emphasis on the

importance of customization and accessibility. Re-

garding the online medical records that are becom-

ing more and more prevalent these days, (Huvila

et al., 2018) examines differences in the way older

and younger adults experience reading these records.

Studies reveal that gender also plays a role in dif-

ferences in the search for online health information

among older adults (Picchiello et al., 2021). Men tend

to view the Internet as more useful and trustworthy

for health decisions compared to women. The source

of information also differs: men are more likely to

use official sources, while women focus on alterna-

tive sources like social media. In addition, (Paimre

and Osula, 2022) observes that during the COVID-19

crisis, men showed a greater readiness for vaccina-

tion, while women focused on alternative treatments.

Even if older adults generally experience more

frustration with online health information seeking

(Ybarra and Suman, 2008), internet health informa-

tion seeking appears to enhance patient-provider rela-

tionships across age groups and genders.

3 STUDY DESIGN

The standards of the scientific community regarding

case surveys, as described in (Ralph, 2021) were used

when conducting this research. Before establishing

the methodology, we initially evaluated the scope of

the investigation.

Scope: The purpose of the study was to deter-

mine how gender and availability of information in-

fluence patient satisfaction with that provided by on-

line sources or digital sources about the treatment of

blood clots.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

378

Who: Patients, age 60+, from the Blekinge re-

gion, Sweden, treated for blood clots.

When: In the period between May and June 2024,

we asked patients who receive blood clot treatment to

complete a postal survey to capture their perspective

on our research topic.

How: We applied a standard strategy, analyzing

the responses quantitatively.

Participation: The survey was anonymous, and

participation in the study was voluntary, ensuring that

we were unable to map the participants with the re-

sponses.

3.1 Survey Design

After we established the purpose of the investigation

and formulated the research questions, we prepared

the survey questions. The process was iterative: first,

we elaborated on a set of questions, then two au-

thors discussed, proposed, and validated changes to

the form and structure of the questions. The sec-

ond draft was discussed with the third author, and we

agreed on the final versions of the questions.

We decided to use eight closed questions. The

first question was used to determine the groups and

categories of participants (men versus women). The

second question was to ensure the eligibility of the

participant for the study. The next five questions are

related to sources of information and the last refers to

the perceived quality of the information. The ques-

tions asked in the survey are listed in Table 1.

The answer to question seven was a

multiple-choice item with the options: 1177.se;

Blodtroppsskolan.se; The pharmaceutical company’s

own website; FASS; Online medical journal/scientific

article; Other website; Other sources (not online).

We intended with this question to identify the most

popular online source of information.

3.2 Participants

All elderly patients (age 60+) in the target region who

were treated for blood clots made up the target audi-

ence for our survey. Consequently, there were 120

people in the participant set to study. The sample is

small because it is not a common disease.

3.3 Methodology

The methodology used in this study is similar to those

employed in other similar types of research (Ralph,

2021).

For the study, we conducted a survey that included

eight closed questions. Accountable questions make

it easier to work with and interpret data.

To balance the ratio of women versus men in

participants in the survey, we adjusted the discrep-

ancy between sample proportions and target popula-

tion proportions using the standard procedure used in

practice (De Leeuw et al., 2012): weighting the re-

sponses according to gender.

To address this, we took the following steps:

• Step 1: Define Proportions

The proportions of respondents in the sample and

the corresponding proportions in the target popu-

lation were identified for each group.

• Step 2: Calculate Weights

Weights were calculated as the ratio of the tar-

get population proportion to the sample propor-

tion for each group. This ensured that each group

was appropriately represented in the analysis.

w

group

=

p

target, group

p

sample, group

• Step 3: Apply Weights

The calculated weights were assigned to each re-

spondent based on their group. These weights

were incorporated into the analysis to compen-

sate for sample imbalance, ensuring that the re-

sults better reflected the target population.

• Step 4: Analyze Weighted Data

All statistical analyses, including descriptive

statistics and regression models, were performed

using weighted data to provide representative re-

sults. For all analyses, we used the PSPP 2.0.0

software.

3.4 Data Collection

Data were collected in a postal survey. Patients re-

ceived a letter containing all the information about

the study, the questionnaire, and a return envelope.

In addition, the meta-information included informed

the subject about the purpose and content of the study

(following the procedures of (De Leeuw et al., 2012)),

as well as instructions on how to complete the sur-

vey. We ensure that in this self-administrated ques-

tionnaire, the respondent received all the information.

The process consisted only of one phase, the data

collection. We skipped the typical first phase, a con-

tact phase, to eliminate any bias related to Q4; usually

this step is made by a member of the hospital, which

could lead to a different answer to this question. The

agreement and the conditions of the full anonymity of

the survey were included in the meta-information.

The Role of Gender and Clear Communication in Digital Health Engagement for Blood Clot Management

379

4 RESULTS

The data collected from the survey are analyzed in

this section, and the results are outlined. In our anal-

yses, we took into account the different gender per-

spectives.

We received 91 questionnaires back, and only one

of them was invalid (the age of the respondent was

under 60 years old). The result is good, considering

that postal surveys have the lowest rate of responses

in general (Edwards et al., 2002).

Q1. Please specify your gender.

Of the respondents, 57.7% were men and the rest were

women. In the target region, according to the statistics

for 2023 (Statistics Sweden, 2023), there are 47.9%

men and 52.1% women. The results have statistical

significance even if there is this discrepance between

the men/women ratio in the 60+ population in the re-

gion compared to the ratio of participants due to the

tendency among older women to be rectulant in an-

swering surveys compared to men of the same age,

see (Porter, 2004).

To cope with this difference, we will weight the

answers according to the methodology described in

subsection 3.3.

We define the proportions in the sample:

p

sample,men

= 57.7% = 0.577

p

sample,women

= 42.3% = 0.423;

in the target population:

p

target,men

= 47.9% = 0.479

p

target,women

= 52.1% = 0.521.

We calculate the weights for each gender:

w

men

≈ 0.83

w

women

≈ 1.23.

We will apply these to all computations by assigning

a weight of 0.83 to each man’s response and, respec-

tively, a weight of 1.23 to each woman’s response.

As we can see in Table 2, after applying the

weights, we have the same ratio of men/women in the

sample as in the target population.

Table 2: Frequency Distribution of males and females that

agreed to participate in the survey and send back the filled-

out questionnaires.

Answers Freq. Percent

women 46.74 52.0%

men 43.16 48.0%

Total 89.90 100.0%

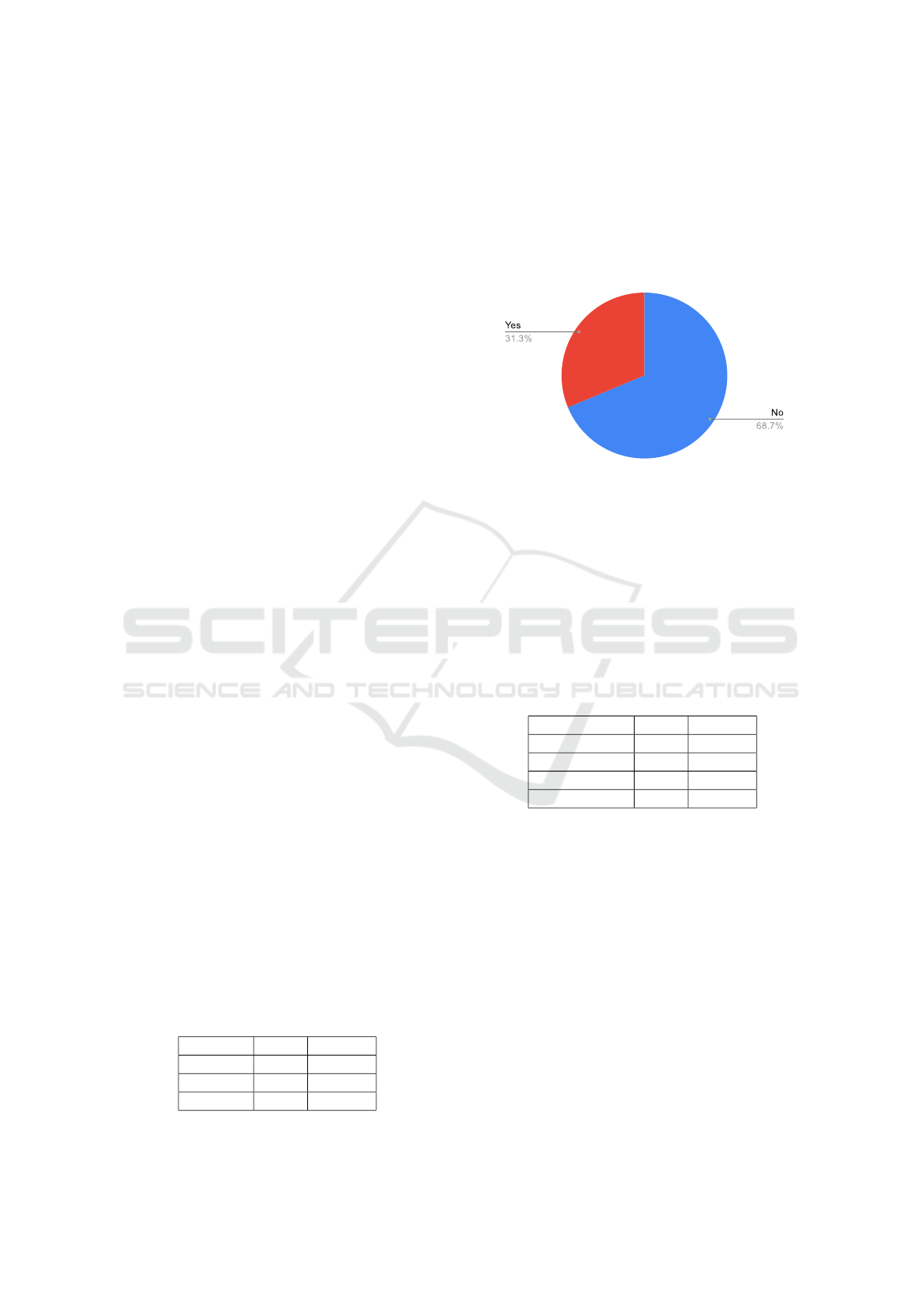

Q3. Did you use the Internet to search for infor-

mation about your condition and medications in

relation to your illness?

As we can see in Figure 1, 31.3% of the respondents

search the Internet for information related to their ill-

nesses and how they can be treated (in emergency

rooms or by appropriate medication).

Figure 1: Frequency Distribution of participants in the study

that were searching the Internet for information.

Q4. After leaving the hospital, did you receive

information from a nurse about blood thinning

treatment?

The percentage of patients who confirm that a nurse

answered their questions and informed them about

their treatment is 13.3%, for a meeting in person and

51.1% by phone, as we can see in Table 3 .

Table 3: Frequency Distribution of subjects that declare that

they received direct information from a nurse about their

disease.

Answers Freq. Percent

No 32 35.6%

Yes, in person 12 13.3%

Yes, by phone 46 51.1%

Total 90 100.0%

Q5. Have you received an information brochure

about the emergency unit and one brochure on

medication?

Table 4 presents the responses rates to this question.

It is evident that over fifty percent obtained brochures

supplied by the hospital, with only 14% that did not

get any of them. We investigated the possibility that

these patients sought alternative information online;

however, this was not substantiated by data, as none

of the patients who did not receive printed material

searched the Internet.

Q6. Did you think the written information about

the emergency unit was a good support in your

treatment?

Another potential incentive for online searches that

we examined was related to patients’ belief that the

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

380

Table 4: Frequency Distribution of people that receive the

written brochure about their medication and the help pro-

vided by the emergency unit regarding their illness.

Answers Freq. Percent

No 14.82 16.5%

Yes, both 55.28 61.5%

Yes, only on medication 19.80 22.0%

Yes, only about emergency 00.00 00.00%

Total 89.90 100.0%

textual support was inadequate. Only 12% of the par-

ticipants deemed the information inadequate, and of

them, merely 2 sought additional sources online. So,

this is also not an indicator for a positive answer to

Question 3.

Table 5: Frequency Distribution of people that consider

that the written information provided good support for their

treatment against blod clodth.

Answers Freq. Percent

No 12 13.3%

Yes 70 77.8%

No answer 8 8.9%

Total 90 100.0%

Q7. What pages/sources?

The responses to this question are centralized on the

following list:

• 1177.se: 22 responses (24.4%)

• Blodproppsskolan.se: 2 responses (2.2%)

• The pharmaceutical company’s own website: 0

responses (0.0%)

• FASS: 2 responses (2.2%)

• Online medical journal/scientific article: 0 re-

sponses (0.0%)

• Other page: 4 responses (4.4%)

• other sources (not online): 26 responses (28.9%)

• No answers: 34 responses (37.8%)

Observe that the percentage of people who used

online sources of information differed by exactly

2.2% between Q3 and Q7. One reason for this may be

that the FASS mobile application may not be consid-

ered an online source of information for older people

despite its actual status.

Q8. Is it clear to you as a patient what the emer-

gency unit can offer you for support?

As we can see from Table 6, 40% of the subjects an-

swered negatively to this question and 60% consid-

ered that they received clear information about the

support offered by the emergency unit.

Results Analyzes. In order to get a deeper under-

standing of the searched phenomena, we performed a

series of binary logistic regressions.

Table 6: Frequency Distribution of subjects that consider

that they have comprehensive, clear information about the

services offered by the emergency unit.

Answers Freq. Percent

No 36 40.0%

Yes 54 60.0%

Total 90 100.0%

First, we do a regression with the dependent vari-

able, the answer to Q3, and the sex of the subject is

the independent variable.

The resulting model, which was designed to pre-

dict the likelihood that a senior person would search

for information online based on gender, demonstrated

a modest fit to the data, as indicated by the value of

−2 Log Likelihood 109.97. The pseudo R

2

values

Cox & Snell (R

2

= 0.05) and Nagelkerke (R

2

= 0.07),

suggest that the gender explained 5% to 7% of the

variance in Q3. This indicates that while sex has a

statistically significant effect, the overall explanatory

power of the model is limited, and as a consequence,

we need to refine it (for example, by adding more vari-

ables).

Regarding the predictor significance, the regres-

sion results showed that gender is a statistically sig-

nificant predictor of the likelihood of searching the

Internet for information (B = −1.01, p = 0.038). The

odds ratio for gender is given by:

Odds Ratio (Exp(B)) = e

−1.01

≈ 0.36

This indicates that for men, the odds of searching

for information online increase by 64% compared to

women. Thus, individuals classified as women are

significantly less likely to fall into the ”search” cate-

gory.

If we consider as predictors the answers to ques-

tions four and five, we find that this explains only a

modest portion of the variance in the answers to Q3,

suggesting that additional factors may influence the

outcome.

In another analysis, we examine the relationship

between the perception of understanding the services

provided for this disease in the emergency room (the

independent variable) and the disposition to search

for information online (the dependent variable). The

analysis showed that understanding what the emer-

gency unit can offer for support is a significant fac-

tor in predicting whether patients use the Internet to

search for information on their condition and med-

ications related to their illness. The found coeffi-

cient (B = 1.54) indicates that for each one-unit in-

crease in clarity about the emergency unit’s support,

the log-odds of using the Internet to search for infor-

mation increase by 1.54. Furthermore, the odds ratio

(Exp(B) = 4.67) suggests that higher clarity makes

The Role of Gender and Clear Communication in Digital Health Engagement for Blood Clot Management

381

the likelihood of using the Internet approximately

4.67 times greater, holding all other factors constant.

This effect is statistically significant (p = 0.026), con-

firming that clarity about the emergency unit’s sup-

port is a meaningful and impactful predictor of Inter-

net usage for health-related information.

Performing the analysis in reverse, we found that

using the Internet to search for information is not a

significant predictor of clarity about the emergency

unit’s support (p = 0.074 > 0.05). The weak explana-

tory power of the model and the classification imbal-

ance limit its utility.

Results Discussion

Gender and Internet Usage. Gender significantly pre-

dicts older patients’ use of the Internet for health-

related information (B = −1.01,p = 0.038). Men

were 64% more likely than women to use digital re-

sources, as indicated by the odds ratio (Exp(B) =

0.36). The model only explains a small portion of

the variance in this behavior, as shown by the pseudo

R

2

values (Cox & Snell R

2

= 0.05, Nagelkerke R

2

=

0.07). These findings indicate that, while gender is

important, other factors also influence Internet use,

emphasizing the need to include additional predictors.

These can be, for example, digital literacy, access to

technology, or health-related concerns.

Clarity of Emergency Unit Information and Internet

Use. The clarity of information in the emergency

unit regarding anticoagulant treatment and blood clot

management emerged as a significant and impactful

predictor of Internet use (B = 1.54, p = 0.026). The

odds ratio (Exp(B) = 4.67) shows that patients who

perceive more clarity in the support of the emergency

unit are 4.67 times more likely to use the Internet to

search for health-related information. This suggests

that transparent and well-communicated emergency

unit support can empower patients to actively manage

their health using online resources.

When the analysis was reversed, the model re-

vealed no significant relationship between Internet us-

age and the clarity of emergency unit support (p =

0.074). This asymmetry demonstrates that, while

clear communication can encourage Internet use, sim-

ply searching online does not necessarily improve pa-

tients’ understanding of emergency services.

5 THREATS TO VALIDITY

Through the analysis, one of our goals was to mini-

mize any possible risks. We also attempted to miti-

gate the potential threats to validity that were identi-

fied during the investigation. Three aspects were con-

sidered following the standard guidelines: construct

validity, internal validity, and external validity. For

internal validity, we focus specifically on the partic-

ipant set, participant selection, dropout contingency

measures, and author biases.

Construct Validity. To eliminate the authors’ bi-

ases, the questions were prepared using a multi-step

method indicated in the Survey Design. The recom-

mended survey questions were in line with the study

goals given in the introduction.

Internal Validity. We found several possible inter-

nal risks, including participation and participant se-

lection, dropout rates, author subjectivity, and ethics.

Participant Set and Participant Selection. Ev-

ery postal survey included a notice of the re-

search’s aims as well as an invitation to partici-

pate. The letters were sent to all 60+ patients that

were receiving blood thining medication from that

region. As a result, the target group of participants

was well determined, removing possible hazards

related with the participant pool or their selection.

More than that, to ensure eligibility, we included

a question regarding age and made it clear that it

referred to the blood clot condition.

Drop-outs Rates. Postal surveys are voluntary by

default. There are very few methods to reduce

the drops-out rates. We enclosed an appealing

and clear meta-information outlining the benefits

of our research; the letter had a friendly design;

and we limited the number of questions in an at-

tempt to increase participation. We also waited

two months for the letters with the responses to

return to the hospital until we declared the survey

closed.

Author Subjectivity. We considered and inves-

tigated the possibility of subjectivity in data pro-

cessing. We did the analysis in accordance with

the specified data processing standards and we

crossvalidated each other’s work.

Ethics in Our Research. We exhibited our com-

mitment to ethics by informing participants about

our objective for collecting data, our anonymous

data collection method, and our planned use of the

data. In addition, we made it clear that participa-

tion was voluntary, and some indeed opted not to

participate. In the letter accompanying the ques-

tionnaire, we notified the subject that by returning

the letter with their responses, they consent to par-

ticipate in the study.

The Swedish Ethics Authority (Etikpr

¨

ovnings

myndigheten www.etikprovningsansokan.se) re-

ceived the study proposal for approval after decid-

ing on the format, questions, and survey design,

and they agreed with the study in this form. One

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

382

main reason for this approval was that we did not

request any patient information in the question-

naire that could potentially identify the subject.

External Validity. We investigate the feasibility of

generalizing our study’s findings to a wider patient

population. It is noted that generalization to the entire

society is not attainable, since we examined a specific

cohort from a particular location. Nevertheless, we

might cautiously generalize to other elderly patients

from that region.

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This study explored factors that influence the use of

the Internet by older patients to access health-related

information, focusing on gender differences and the

clarity of the information provided by emergency de-

partments about anticoagulant treatment and blood

clot management. The findings highlight key insights

into patient behavior and areas for improvement in

healthcare communication.

The results show that gender significantly predicts

Internet use among older patients. Men are 64% more

likely than women to use digital resources for health-

related information, as indicated by the odds ratio.

This finding underscores the persistent gender dispar-

ity in the adoption of online tools for self-education

about health. However, the model explains only a

small portion of the variance in Internet usage behav-

ior, suggesting that there are other additional factors

that may also play a significant role. These results

emphasize the need for targeted strategies to support

older women in accessing and using online health in-

formation, potentially through education or improved

access to technology.

The clarity of the information provided by emer-

gency services also emerged as a predictor of Inter-

net usage. Patients who perceive higher clarity about

the services offered by emergency units are 4.67 times

more likely to search online for information related to

their condition and medications. This finding high-

lights the importance of clear and transparent com-

munication from healthcare providers in empowering

patients to actively manage their health using digital

resources.

In contrast, a reverse analysis revealed that In-

ternet usage does not significantly predict patients’

understanding of the support provided by emergency

units. This asymmetry suggests that while clear com-

munication from healthcare providers can encourage

patients to seek information online, online searches

alone do not necessarily improve patients’ under-

standing of healthcare services. This underscores the

need for emergency units to prioritize direct commu-

nication strategies to ensure patients fully understand

the available support.

The findings have several important implications

for healthcare providers and policy makers. First, ad-

dressing gender disparities in Internet use requires tar-

geted interventions to improve digital literacy and ac-

cess to technology, particularly for older women. Ed-

ucational programs tailored for older patients could

help bridge the gap and increase the adoption of on-

line resources.

Second, the strong relationship between the clar-

ity of emergency unit information and Internet us-

age highlights the critical role of effective commu-

nication. Emergency units should prioritize provid-

ing clear, accessible and comprehensive information

about available services, especially for complex con-

ditions such as blood clot management.

Third, while encouraging the use of the Internet

can empower patients, it is not a substitute for di-

rect communication from healthcare providers. Pa-

tients benefit most when clear guidance from health-

care professionals complements their online searches.

Therefore, a balanced approach that combines digital

engagement with personalized communication is es-

sential.

These findings suggest that patients who receive

clear information may feel more empowered to inves-

tigate related topics online. Alternatively, individuals

who receive ambiguous information may feel over-

whelmed or discouraged to seek further clarification.

A relevant conclusion is that explicit communication

from physicians may indicate to patients that further

information is beneficial and worth pursuing.

An additional significant conclusion is derived

from the responses to inquiries concerning the source

of the online material. The search predominantly

occurs on official sites or applications, with only 2

percent of subjects conducting searches in unofficial

sources. Furthermore, popular information tends to

be the most straightforward and comprehensible, such

as government or hospital manuals, rather than more

advanced sources, such as scientific publications or

pharmaceutical websites.

To improve the management of anticoagulant ther-

apy, future research should focus on developing com-

prehensive educational content, determining optimal

delivery formats, and evaluating the impact of digi-

tal interventions on health outcomes and clinical prac-

tice.

Future research may examine whether competen-

cies and/or experience in IT usage, or motivation to

The Role of Gender and Clear Communication in Digital Health Engagement for Blood Clot Management

383

use IT applications among women and men, influ-

ence the findings. Additionally, if these issues impact

the utilization of IT applications or what other factors

may influence their use, such as limited access to IT

applications.

7 AI DISCLOSURE

The QuillBot AI tool was used in the preparation of

this manuscript for paraphrasing and language cor-

rection purposes. The AI tool did not assist in the

creation of original content, the formulation of the re-

search design, the analysis of the data, or the interpre-

tation of the findings. The authors take full responsi-

bility for the content, accuracy, and conclusions artic-

ulated in this paper.

REFERENCES

Bujnowska-Fedak, M. M. and Mastalerz-Migas, A. (2015).

Usage of medical internet and e-health services by the

elderly. Environment Exposure to Pollutants, pages

75–80.

De Leeuw, E. D., Hox, J., and Dillman, D. (2012). Interna-

tional handbook of survey methodology. Routledge.

Edwards, P., Roberts, I., Clarke, M., DiGuiseppi, C., Pratap,

S., Wentz, R., and Kwan, I. (2002). Increasing re-

sponse rates to postal questionnaires: systematic re-

view. BMJ, 324(7347):1183.

Fischer, S. H., David, D., Crotty, B. H., Dierks, M., and

Safran, C. (2014). Acceptance and use of health

information technology by community-dwelling el-

ders. International journal of medical informatics,

83(9):624–635.

Freund, O., Reychav, I., McHaney, R., Goland, E., and

Azuri, J. (2017). The ability of older adults to use

customized online medical databases to improve their

health-related knowledge. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 102:1–11.

Huvila, I., Eriksson-Backa, K., Moll, J., Myreteg, G., and

H

¨

agglund, M. (2018). Differences in the experi-

ences of reading medical records online: elderly, older

and younger adults compared. Informaatiotutkimus,

37(3):51–54.

Kagansky, N., Knobler, H., Rimon, E., Ozer, Z., and

Levy, S. (2004). Safety of anticoagulation therapy

in well-informed older patients. Archives of Internal

Medicine, 164(18):2044–2050.

Marschollek, M., Mix, S., Wolf, K.-H., Effertz, B., Haux,

R., and Steinhagen-Thiessen, E. (2007). Ict-based

health information services for elderly people: Past

experiences, current trends, and future strategies.

Medical informatics and the internet in medicine,

32(4):251–261.

Olomu, I. O., Barnes, G., Kaatz, S., Haymart, B., Gu, X.,

Kline-Rogers, E., Alexandris-Souphis, T., Kozlowski,

J., Ahsan, S., Besley, D., et al. (2014). Technology

use among patients undergoing warfarin therapy: A

report from the michigan anticoagulation quality im-

provement initiative (maqi2). Circulation: Cardiovas-

cular Quality and Outcomes, 7(suppl 1):A176–A176.

Paimre, M. and Osula, K. (2022). Gender differences in

ict acceptance for health purposes, online health infor-

mation seeking, and health behaviour among estonian

older adults during the covid-19 crisis. In ICT4AWE,

pages 134–143.

Picchiello, M., Rule, P., Lu, T., and Carpenter, B. (2021).

Gender differences in online health-related search be-

haviors among older adults. Innovation in Aging,

5(Suppl 1):657.

Porter, S. R. (2004). Raising response rates: What

works? New directions for institutional research,

2004(121):5–21.

Ralph, P. (2021). Acm sigsoft empirical standards for

software engineering research, version 0.2. 0. URL:

https://github. com/acmsigsoft/EmpiricalStandards.

Schillinger, D., Machtinger, E. L., Wang, F., Palacios, J.,

Rodriguez, M., and Bindman, A. (2006). Language,

literacy, and communication regarding medication in

an anticoagulation clinic: a comparison of verbal vs.

visual assessment. Journal of health communication,

11(7):651–664.

Sim, V. and Galbraith, K. (2020). Effectiveness of multime-

dia interventions in the provision of patient education

on anticoagulation therapy: A review. Patient Educa-

tion and Counseling, 103(10):2009–2017.

Statistics Sweden (2023). www.scb.se, Accesed in Decem-

ber 2024.

Torn, M., Bollen, W. L. E. M., van der Meer, F. J. M.,

van der Wall, E. E., and Rosendaal, F. R. (2005).

Risks of oral anticoagulant therapy with increasing

age. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(13):1527–

1532.

Wang, M., Swinton, M., Troyan, S., Ho, J., M Siegal,

D., Mbuagbaw, L., Thabane, L., and M Holbrook,

A. (2022). Perceptions of patients and healthcare

providers on patient education to improve oral antico-

agulant management. Journal of Evaluation in Clini-

cal Practice, 28(6):1027–1036.

Waterworth, S. and Honey, M. (2018). On-line health seek-

ing activity of older adults: an integrative review of

the literature. Geriatric Nursing, 39(3):310–317.

Ybarra, M. and Suman, M. (2008). Reasons, assessments

and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses

of internet health information. Health education re-

search, 23(3):512–521.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

384