Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering

Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange

Ana Carla Amaro

a

and Ligia Kallas

b

DigiMedia - Digital Media and Interaction Research Centre, University of Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: Grandparents, Grandchildren, ICT, Digital Media, Learning, Knowledge Sharing, Intergenerational

Relationships, Escape Room.

Abstract: This exploratory study investigates the role of digital media and technology in shaping intergenerational

relationships between grandparents and grandchildren, focusing on knowledge exchange and collaborative

interactions. Seventeen participants, consisting of eight grandparents (aged 60–75) and nine grandchildren

(aged 10–18), were involved in a gamified escape room activity designed to foster collaboration. The activity

required participants to solve riddles using digital tools such as smartphones, mobile apps, and social media,

followed by semi-structured interviews to explore their experiences. Results revealed a reciprocal learning

process, where grandchildren often guided grandparents in technology use while grandparents shared cultural

knowledge and traditional skills. The activity highlighted the complementary strengths of both generations,

with grandparents contributing with historical knowledge and grandchildren offering technological expertise.

Despite technological anxiety and generational differences in digital proficiency, the study found that

structured activities like the escape room can enhance collaboration and strengthen intergenerational bonds.

Depending on its use, technology emerged as both a facilitator of connection and a potential barrier. The

findings suggest that digital tools can significantly bridge generational gaps, promote mutual learning, and

foster deeper intergenerational relationships.

1 INTRODUCTION

As in most Western countries, the Portuguese

population is aging, given the increase in life

expectancy. People over 65 have grown by more than

2% annually since 2019. Portugal is the fourth

country in the world with the highest proportion of

older adults, and it ranks 2nd among European Union

countries with the highest rate of population aging,

with 186 older adults for every 100 young people

(PORDATA, 2024).

This phenomenon is creating social challenges

that need to be addressed. One of these challenges is

related to the coexistence between generations,

including between grandparents and grandchildren,

which now happens more frequently and for extended

periods (Fingerman & Birditt, 2020). On the other

hand, changes in family structures and work patterns,

the institutionalization of education and care, as well

as increasingly technological and digitally

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7863-5813

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-9295-390X

interconnected societies are impacting both young

and older, resulting in cultural distance, ageism, and

the loss of opportunities to knowledge and values

transfer (Gallagher, 2019).

Promoting intergenerational relationships,

particularly between grandparents and grandchildren,

is paramount in these demographic changes and

social challenges. Studies show that high levels of co-

residence, contact, and care provision between

grandparent-grandchild are linked to more stable

exchanges and interactions over time (Pasqualini et

al., 2021), contributing to the transmission of cultural

heritage and historical knowledge, the sharing of

memories, and the promotion of active aging and

well-being (Ramos, 2013). As observed by Trujillo-

Torres et al. (2023) in a recent systematic literature

review, promoting intergenerational dialogue is one

of the most frequently used strategies to promote

meaningful learning, having a positive impact in

many areas, such as attitudes, well-being, and

Amaro, A. C. and Kallas, L.

Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange.

DOI: 10.5220/0013488000003938

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 389-397

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

389

happiness, improvement of family relationships,

promotion of social and human values, and

combating the generational digital divide, among

others.

On the other hand, and despite the persistence of

the digital divide, older adults have increasingly

become more willing to use technologies and digital

media in recent years, and digital interactions are

emerging as a significant form of communication,

complementing traditional face-to-face and telephone

communication (Barbosa Neves & Vetere, 2019;

Arpino et al., 2022). Maintaining a connection with

their grandchildren is among the main reasons and

motivations for older adults to use technology and

social media (Wei et al., 2023; Ivan & Fernández-

Ardèvol, 2017), and those can play an important role

in supporting intergenerational communication, play

and learn (Yuan et al., 2024).

As such, this paper describes research focused on

understanding how digital media and technology

interfere with reciprocal learning and

intergenerational solidarity between grandparents and

grandchildren.

2 BACKGROUND

Family relations have always been central to creating

solidarity and identity and transmitting cultural and

moral values. As the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong

Learning (2015) highlights, familial intergenerational

learning practices are rooted in all cultures and

present an opportunity for adults and younger to

become lifelong learners. Grandparents, in particular,

can play an essential role in their grandchildren’s

formal and informal education, facilitating children's

learning through intergenerational play and creating

linguistic and cultural heritage learning spaces (Keary

et al., 2024; Kanyal, M., Mangione, D. and Luff, P.,

2024; Barragán-Medero et al., 2024). Besides, these

interactions and knowledge transfer represent a

reciprocal process for both generations, also

benefitting grandparents (Mendelová & Zelená,

2021; Harwood, 2007). Research has shown that such

interactions can improve cognitive health in older

adults, combat social isolation, and provide a sense of

purpose (Stephan, 2024; Döring et al., 2022; Lai, Li,

& Bai, 2021; Lyu et al., 2020).

Some studies state that adolescence introduces a

unique challenge to intergenerational exchange, as

teenagers, influenced by peers and digital culture,

may sometimes prioritize advice and validation from

friends over guidance from family members

(Jassogne & Zdanowicz, 2020; Strom & Strom,

2015). However, other authors emphasize that the

quality of contact with grandparents, rather than age,

is the key factor influencing children and adolescents'

views about older adults (Soliz & Harwood, 2003;

Harwood, 2007; Strom & Strom, 2015; Flamion et al.,

2019). As highlighted by these researchers, the

exchange of intergenerational knowledge is

influenced by relational proximity, the quality of the

bond, and the context of the interaction. When

relationships between grandparents and

grandchildren lack closeness, knowledge

transmission and interactivity are significantly

hindered (Forghani & Neustaedter, 2014). This

dynamic underscores the importance of fostering

strong intergenerational relationships to facilitate the

sharing of cultural heritage and practical life skills.

Studies also suggest that grandparents, and

especially grandmothers, transmit a wide range of

knowledge, from moral and ethical principles to

practical skills such as cooking, gardening, and even

study habits (Modin, Erikson & Vågerö, 2013;

McConatha, McConatha & DiGregorio, 2021).

Conversely, grandchildren often serve as

generational bridges, sharing insights into

contemporary culture, acting as tutors to their

grandparents regarding social norms, and using new

technologies, thus enhancing digital literacy and

reducing technology-related anxiety among older

adults (Barbosa Neves & Fernandes, 2016).

As far as digital technologies and social media are

concerned, research underlies its potential to foster

intergenerational engagement, namely between

grandparents and grandchildren, in playful and

educational activities (Kaplan et al., 2013; Döring et

al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2024). For example, video chat

has proved effective in ensuring culture-sharing

between grandparents and grandchildren during the

COVID-19 pandemic, namely by supporting

engagement in storytelling and conversations about

traditions, holidays, popular culture, and other themes

(Piper et al., 2023). However, although a few studies

focus on how digital media can facilitate joint media

engagement between grandparents and grandchildren

(Amaro, Oliveira & Veloso, 2017), research is still

limited, focusing primarily on parent-child

relationships. As such, this study is particularly

interested in how grandparents and grandchildren can

collaboratively use technology to solve problems and

how learning and knowledge exchange happen in that

context.

IS4WB_SC 2025 - Special Session on Innovative Strategies to Enhance Older Adults’ Well-being and Social Connections

390

3 METHODS

This qualitative and exploratory study aimed to

understand the role of digital media and technological

devices in intergenerational relationships between

grandparents and grandchildren, particularly in

knowledge exchange and collaborative interactions.

As such, the following main goals were identified: i)

To explore how grandparents and grandchildren

perceive the role of technology in their lives and

relationships; ii) To analyze intergenerational

knowledge exchange mediated by digital media and

technology in the context of a gamified escape-room

type activity. Thus, data was collected through an

escape room activity and individual interviews with

grandparents and grandchildren from the Aveiro

region.

3.1 Participants

The study was conducted with 17 participants,

comprising eight grandparents (aged 60–75) and nine

grandchildren (aged 10–18), selected through

purposive and convenience sampling. These

grandparents and grandchildren cumulatively met the

criteria of having some technological and digital

literacy, having access to or owning up-to-date

technological devices, and expressing a willingness to

participate. This ensured that the participants had the

minimum skills to engage in the challenges proposed

during the gamified escape room activity. However,

the non-inclusion of participants without

technological literacy adds to the limitation of using

a small sample, preventing the generalization of the

results.

The grandparents selected comprised a group of

seven women and one man, with varying academic

qualifications - although the majority had more than

the 4

th

-grade primary education - and with levels of

digital literacy mostly considered low or medium, as

shown in Table 1.

The group of grandchildren was constituted by

nine participants (with two sisters among them),

seven of whom were girls and two boys with basic

digital literacy and aged between 10 and 17.

However, the majority were between 10 and 12, as

shown in Table 2.

Participants were also characterized by their

home proximity and the weekly regularity of face-to-

face meetings. As shown in Table 3, all the

grandparents and grandchildren lived in proximity

and met face-to-face at least 3 times a week, 6 times

a week being the most frequent situation.

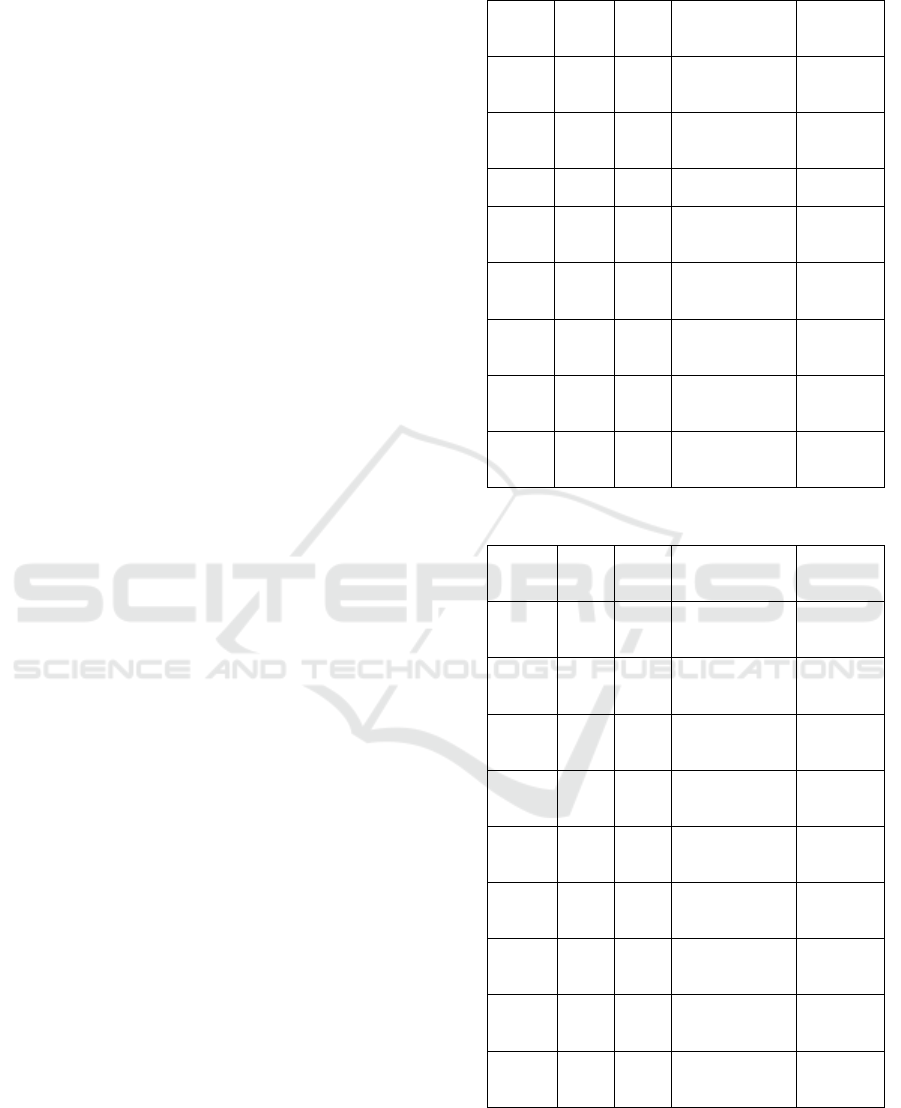

Table 1: Grandparents characterization.

GP

Age

Gen-

der

Academic

Qualifications

Level of

Digital

Literacy

GP01

66

F

Primary

education

(4th grade)

Low

GP02

63

F

Primary

education

(4th grade)

Low

GP03

72

M

Vocational

education

Medium

GP04

66

F

Higher

Education

(short cycle)

Medium

GP05

69

F

Higher

Education

(1st cycle)

High

GP06

68

F

Higher

Education

(short cycle)

Medium

GP07

74

F

Higher

Education

(short cycle)

Low

GP08

67

F

Primary

education

(4th grade)

Medium

Table 2: Grandchildren characterization.

GC

Age

Gen-

der

Academic

Qualifications

Level of

Digital

Literacy

GC01

12

F

Primary

education

(6

th

grade)

Low

GC02

10

F

Primary

education

(4

th

grade)

Medium

GC03

12

M

Primary

education

(6

th

grade)

High

GC04

12

F

Primary

education

(6

th

grade)

Medium

GC05

17

M

Secondary

Education

(12

th

grade)

High

GC06

10

F

Primary

education

(5

th

grade)

Medium

GC07.

1

16

F

Secondary

Education

(11

th

grade)

High

GC07.

2

10

F

Primary

education

(5

th

grade)

Medium

GC08

10

F

Primary

education

(4th grade)

High

Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange

391

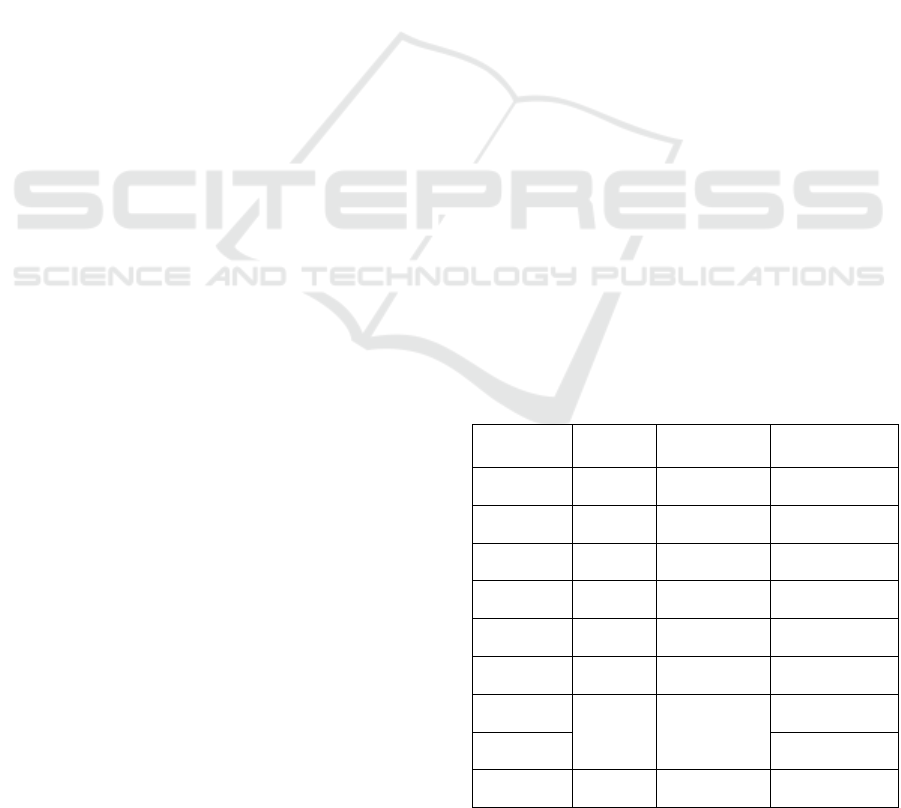

Table 3: Participants’ proximity and frequency of weekly

meetings

Pairs of

participants

Home proximity

Weekly frequency

of meetings

GP01/GC01

Neighbors

6

GP02/GC02

Same neighborhood

3

GP03/GC03

Same neighborhood

6

GP04/GC04

Neighbors

6

GP05/GC05

Same neighborhood

6

GP06/GC06

Same city

5

GP07/GC07.1

Same city

3

GP07/GC07.2

Same city

4

GP08/GC08

Same house

7

3.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection occurred in the context of a gamified

escape room activity and following semi-structured

interviews.

Escape room games are team-based physical

games in which teams of players discover clues, solve

riddles, and accomplish tasks to find a way to escape

a closed room. These experiences usually start with

the players meeting their gamemaster, who introduces

the backstory and gives them the game's rules. As

Nicholson (2015) points out, escape rooms require

team members to rely on each other, collaborate, and

communicate, being appealing and inclusive for a

wide age range and appropriate for intergenerational

groups.

For this study, an activity of this type was

conceptualized, tested, and implemented, aiming to

involve teams of grandparents and their

grandchildren in finding clues and solving riddles to

get out of a closed room - called the Scientist's Office.

The participants had digital media and technology

(like mobile devices, mobile apps, QR codes, social

media,...) at their disposal so that, together with

general knowledge, they could complete the tasks and

get out of the room in a certain amount of time.

According to the activity backstory, Portugal had

suffered a biological attack, and some citizens were

infected by a virus that was activated using

technology. The antidote to this virus was hidden in

the office of a renowned Portuguese scientist

(corresponding to the room where the activity

occurred), and to discover it, participants had to

follow the clues and unravel the riddles. However,

just before entering the office, the blood tests carried

out by the Portuguese government revealed that the

grandchildren were infected with the virus and,

therefore, could not handle any technological devices.

The aim was to contextualize that the grandparents

had to handle the smartphone handed to the

participants before they entered the room, which was

prepared to resemble a scientist's abandoned office

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Scientist's Office.

The activity was validated through a pilot study

involving different participants: two pairs of young

people aged 17 to 20 to validate the gamified activity

mechanics and access logistic issues, and one other

pair, with a 63-year-old and a 17-year-old participant,

to validate the difficulty level and the potential of

clues, riddles, and tasks to elicit communication,

cooperation and knowledge sharing. The activity's

backstory and rules were presented to participants

before entering the room. After carrying out the

activity, the participants were asked to point out

flaws, the need for changes, or any difficulties they

encountered.

Following this pilot application of the gamified

activity, some adjustments were made, such as

changing the layout of some items in the room and

paying attention to some points of operation, such as

the dynamic of asking the research team for help if

necessary.

During the main study, seven pairs and a trio of

grandparents and grandchildren tried to escape the

room. In its final layout, the room was separated into

three distinct spaces: 'The workbench', in which the

participants could find a microscope, pipettes, water

heater, periodic table, and other items that scientists

use, and where clues 1 and 2 were positioned; 'The

desk', containing a typewriter, lamp, folders,

documents, and a telephone, and where the fourth

clue was located; and finally, 'The locker', that was

initially locked and, once opened, contained the

antidote.

Five clues were provided, the first of which, when

they entered the room, referred to one of the images

placed on the room wall: a photo of the famous

Portuguese Fado singer Amália Rodrigues. This clue

involved reading the QR Code associated with the

image, which would lead them to clue number 2. This

IS4WB_SC 2025 - Special Session on Innovative Strategies to Enhance Older Adults’ Well-being and Social Connections

392

second clue consisted of old photos from the main

avenue of Aveiro city and a related poem, and

participants were asked to identify the location. After

unraveling the avenue's name, the participants were

directed to an envelope containing the next clue. This

third clue asked participants to find an old piece of

technology in the room, referring to the typewriter in

'The Desk.' Participants had to turn the platen knob to

advance the page, revealing clue number 4. The

fourth clue asked participants to identify a Portuguese

volcano, including the year it erupted, and post their

answers on a Facebook page dedicated to the project.

Once the correct answer had been posted, the fifth and

last clue was slipped under the door in an envelope

with the locker key. This last task involved taking a

selfie and opening the locker to find the antidote.

Then, the project team would unlock the door to the

room.

The activities were recorded using cameras and

microphones installed strategically in the room. The

furniture, artifacts, and equipment were arranged so

that all the spaces in the room, especially those with

clues and interactions, were filmed and had space for

circulation. The legal aspects of the European

General Data Protection Regulation have been duly

safeguarded.

The records were analyzed using a set of

categories that included the total duration of the

activity and time spent on each clue, collaboration

dynamics, problem-solving strategies, technological

interactions, behaviors, and feelings during the

resolution of the riddles. All observations were noted

down and tabulated to organize better and facilitate

analysis.

After the gamified activity, semi-structured

interviews were scheduled to collect deeper

demographic and digital literacy-related data and to

characterize the quantity and quality of the

relationship between these grandparents and

grandchildren, their perception of their roles,

particularly regarding the transmission of knowledge

and mutual learning, as well as their use of media and

digital technologies.

The interview script and procedures were

validated through a pilot interview with a

grandmother and her granddaughter, aged 60 and 11,

respectively. The questions and procedures proved to

be generally suitable for collecting the necessary data,

with only a few adjustments to the language.

However, as this pair had not participated in the

gamified activity, some questions could not be

validated, so it was only possible to check and adjust

them during the main study.

The relevant parts of the interviews were

transcribed, and themed content analysis was carried

out.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section presents and discusses the study’s

results, structured into two subsections: the gamified

escape room activity outcomes and the insights

gathered from the post-activity interviews. The first

subsection analyses participants' performance in the

escape room activity, highlighting collaboration

dynamics, problem-solving strategies, and

technological interactions. The second subsection

explores the qualitative data from interviews, offering

more profound insights into participants' perceptions

of intergenerational learning and the impact of

technology on their relationships.

4.1 Results from the Gamified Activity

Regarding the total duration of the activity, half of the

cases exceeded the maximum duration of 30 minutes,

as shown in Table 4. As can also be seen, the shortest

time to complete the activity does not always

correspond to pairs with higher levels of digital

literacy (see, for example, pairs GP03/GC03 and

GP04/GC4). However, the pair that took the least

time corresponds to a situation in which both had a

high level of digital literacy. The age of the

grandchildren also influenced the duration of the

activity, with the pairs that included older

grandchildren being quicker.

Table 4: Time taken to complete the gamified activity.

Pairs

Time

GP Digital

Literacy

GC Digital

Literacy

GP01/

GC01

00:38:52

Low

Low

GP02/

GC02

00:31:22

Low

Medium

GP03/

GC03

00:35:13

Medium

High

GP04/

GC04

00:36:12

Medium

Medium

GP05/

GC05

00:14:48

High

High

GP06/

GC06

00:19:49

Medium

Medium

GP07/

GC07.1

00:21:35

Low

High

GP07/

GC07.2

Medium

GP08/

GC08

00:24:32

Medium

High

Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange

393

Concerning the tasks proposed for finding the

clues, it was observed that those in which participants

had to find answers to questions and post on social

media took longer to complete. In these cases,

difficulties with digital and technological means were

also observed to be decisive for the increase in

completion time. Regardless of the time they needed

and the difficulties they experienced, the participants

generally worked together and helped each other to

complete the technological and historical tasks.

Handling the smartphone, especially regarding

the small size of the keyboard, was one of the main

difficulties experienced by the grandparents. These

difficulties stemming from the grandparents' physical

limitations and others, such as not knowing certain

things, like the positioning of the device's camera or

what an app is, made the grandchildren sometimes

impatient: “It is an app, don't you know what an app

is? It is a mobile application, Grandma.” (GC06).

Nevertheless, grandchildren showed interest and

focus and were responsible for passing on

technological knowledge. Grandparents, on the other

hand, took on more of a historian role, paying greater

attention to the details of the activities, although

taking more time to complete them. Grandchildren

were quicker than directing the grandparents, even on

the clue involving finding the typewriter. It was then

the grandparents who, in general, operated the

typewriter to reveal the next clue, teaching their

grandchildren how to do it. This process sparked

interesting conversations about past technology.

The most challenging clue was asking for the

volcano’s identification and the year it erupted.

Participants googled for the information, although

most grandparents already knew at least part of the

answer. The most significant difficulty for the older

generation was using the Google search. Some

peculiarities in searching for the answer highlight that

knowledge exchange occurs non-linearly. In the case

of the pair GP02/GC02, the grandmother, while

trying to understand how to use the Google search,

ended up doing a voice search. When she called her

granddaughter for help, the granddaughter found the

situation amusing: "'Come here' (typed in the search

bar)? What is this? Grandma, did you press this little

microphone? Well, Grandma, that is for when you

want to search, but you do it by voice." (GC02).

After finding the answer, participants needed to

post it on the project’s Facebook page, which was the

most significant challenge. Despite most participants

being Facebook users, they all experienced

difficulties finding the project’s page and making the

post. They ended up asking for help (a knocking code

on the door was previously agreed upon with the

participants in case they needed help or wanted to

leave the room for any reason).

Due to the complexity of the tasks, the pressure to

perform well, or the limitations of time and

knowledge, many grandparents and grandchildren

showed signs of impatience. Both generations

expressed their feelings differently: the younger

generation, which could not use the technology,

tended to pace around the room and often rummaged

through the space, looking for other clues. In

comparison, the older generation focused intently on

using their smartphones and searching for a solution.

As soon as the last clue was unveiled and the pairs

had access to the locker’s key, most grandchildren

went to get the antidote before taking the selfie.

Curiously, four of them took the smartphone from

their grandparents as soon as the antidote was taken!

Despite the various difficulties encountered, the

exchange of knowledge was evident. It was also

noticeable that grandparents did not always need their

grandchildren's help but requested or accepted it. This

was the case with grandparents like GP03 and GP05,

who demonstrated confidence and proficiency with

their smartphones throughout the activity but

encouraged their grandchildren to assist them.

4.2 Results from the Interviews

The interviews showed that, even though they lived

in different proximities, all the participants saw the

other generation more than twice a week and that

these meetings lasted around three to eight hours.

What stands out is that four of the eight pairs

interviewed reported about six meetings a week due

to the grandparents caring for their grandchildren

after school. Most grandparents (seven of the eight

participants) assume this role when parents are away.

The important role that grandparents can play in their

grandchildren's education is emphasized by several

authors (e.g., Kanyal, M., Mangione, D. and Luff, P.,

2024; Barragán-Medero et al., 2024) and was even

acknowledged by the grandparent participants: “But

he does not spend most of his time with his parents,

he spends most of his time without them, doesn't he?

Here, we play a very important role in his education.

And if he was here every day, I think it was only fair

that we intervened.” (GP05).

In the interviews, the grandchildren reported a

very close and intimate relationship with their

grandparents, except in the case of GC03, who

reported a low level of closeness with his grandfather,

describing it as a more cordial and respectful

relationship. Granddaughters GC01, GC4, GC6, and

GC08 reinforced their grandmothers' friends and

IS4WB_SC 2025 - Special Session on Innovative Strategies to Enhance Older Adults’ Well-being and Social Connections

394

confidants’ status. The other grandchildren reported

their friendship with their grandparents, recognizing

them as a haven and a source of complementary

emotional support and knowledge. Seven of the nine

grandchildren interviewed recognize their

grandparents as highly qualified to pass on

knowledge.

However, as far as the exchange of knowledge

and intergenerational learning is concerned, two of

the eight grandparents interviewed, because they do

not consider their life experience to be knowledge, do

not see themselves as being able to teach their

grandchildren, given their low level of academic

qualifications and because they are “too old.” The

majority, however, consider that these exchanges of

knowledge and learning take place either in the

context of their informal socializing or through

strategies and moments in which they try to teach

their grandchildren values, life lessons, and skills that

go far beyond traditional education, such as sewing or

other handicrafts (GP01, GP05, GP06).

When considering technological devices,

grandparents display diverse perspectives. Among

the eight grandparents interviewed, four relied on

their grandchildren to resolve issues with technology.

They recognize the ease their grandchildren showed,

as digital natives, with technology and are even proud

of it. On the other hand, half were critical of the

excessive use of technology, disapproving, for

example, smartphone use at the table during meals:

"Because I think that if it were not for us, he would

come to the table with that thing on, watching videos.

However, when Grandpa or I arrive, he turns it off. It

is a sign of respect, and we appreciate that." (GP05).

Concerns about misuse and premature access to

technology were also prevalent. For example, GP02

said: "[GC2] has one, but the other does not. Well,

[GC2] only got hers this year because she moved to

another school, to the fifth grade. However, honestly,

I think it is too soon."

Regarding technology's role, half of the

grandparents viewed digital devices as tools for

connection and separation. They acknowledged the

Internet's ability to bridge distances and provide

access to knowledge. Still, they noted its potential to

hinder personal interactions: "Excessive use creates

distance, but at the same time, it helps. Resolving

doubts, offering help—it brings people closer."

(GP04). When directly asked about the role of

technology in relationships, opinions varied. Half

believed technology was incompatible with

meaningful interaction and avoided technology

altogether, choosing instead to bond with their

grandchildren over shared hobbies: "No, they are

completely incompatible. If they have their phone in

hand, we are both sitting in silence." (GP03).

The other half saw technology as a topic of

discussion and learning in their daily interactions:

"Resolving doubts and helping each other… it brings

people closer. In my case, [GC4] helps me, and that

is a connection we have." [GP4. Grandmothers like

GP5 and GP06, frequent technology users,

highlighted its role as a tool in their relationship with

their grandchildren.

Regarding the impact of technology on

intergenerational relationships, the grandchildren’s

opinions varied. While three of the nine recognized

the dual role of technology as both a connector and a

divider, they acknowledged that technology could

bring people together over long distances but also

create barriers during face-to-face interactions:

"Sometimes it can bring people closer when they are

far away and talking to everyone. But it can also push

them apart when they are all together and on their

phones." (GC7.1). When asked about the direct role

of technology in their relationships, most agreed that

it plays a significant role, namely as a resource to

support knowledge transfer, helping both generations

to understand old and new concepts by providing

visual help: "Yes, because many times they can

explain things to me, but I cannot imagine it. Then

they can go to the internet, show me pictures or

something, and I can understand better." (GP06).

In summary, both generations recognize

technology as a bridge and a potential barrier in

intergenerational relationships. However, most

participants acknowledged its active role in fostering

learning, communication, and connection across

generations.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This exploratory study examined the role

of technology and digital media in shaping

intergenerational relationships between grandparents

and grandchildren, focusing on knowledge exchange

and collaborative interactions. The research involved

grandparents and grandchildren participating in a

technology-driven gamified escape room activity

designed to foster collaboration and problem-solving,

followed by individual interviews to gather more

profound insights into their experiences and

perspectives.

The results from both the escape room activity and

the interviews confirm that grandparents and

grandchildren engaged in reciprocal learning

processes. Grandchildren often acted as tutors,

Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange

395

guiding their grandparents in navigating technology

and digital tools, while grandparents shared cultural

knowledge and traditional skills, values, and life

experiences. This bidirectional exchange promotes

digital literacy among older adults and enhances the

younger generation’s understanding of heritage and

the acquisition of valuable skills. The gamified

activity highlighted each generation's complementary

strengths and the potential of technology to facilitate

meaningful joint endeavors.

Despite these promising findings, the study

presents some limitations. The small sample

size restricts the generalizability of the results to

broader populations, and the inclusion criteria -

requiring participants to have some pre-existing

familiarity with technology - excluded older adults

with no prior digital experience. Future research

should consider expanding the sample size and

incorporating a wider range of digital literacy levels,

including participants with minimal or no exposure to

digital tools. This would provide a more

comprehensive exploration of the barriers and

facilitators of digital intergenerational engagement.

Additionally, while this study focused on a single

gamified activity, future work could explore the long-

term effects of such initiatives on intergenerational

relationships and digital inclusion. There is

significant potential to scale up the concept,

integrating similar gamified learning

experiences into schools, community centers, and

digital literacy programs for older adults. Moreover,

incorporating augmented or mixed realities could

enhance accessibility and engagement, making these

activities more immersive and adaptable for diverse

populations.

By refining and expanding these approaches,

future research, and practical implementations

could broaden the impact of digital media in fostering

intergenerational collaboration, ensuring that

technology serves as a bridge rather than a

barrier between generations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is financially supported by DigiMedia -

Digital Media and Interaction Research Centre and by

national funds through FCT – Foundation for Science

and Technology, I.P., under the project

UIDB/05460/2020.

REFERENCES

Amaro, A. C., Oliveira, L., & Veloso, A. I. (2017).

Intergenerational and collaborative use of tablets: «in-

medium» and «in-room» communication and

interaction. Observatorio (OBS*), 11(1).

https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS1102017995

Arpino, B., Meli, E., Pasqualini, M., Tomassini, C. &

Cisotto, E. (2022). Determinants of grandparent-

grandchild digital contact in Italy. Genus 78, 20 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-022-00167-5

Barbosa Neves, B. (2019). Ageing and Digital Technology:

Designing and Evaluating Emerging Technologies for

Older Adults. Singapore: Springer. ISBN

9789811336935

Barbosa Neves, B. & Fernandes, A.A. (2016). Generational

Bridge. In C.L. Shehan (Ed.). The Wiley Blackwell

Encyclopedia of Family Studies, First Edition. John

Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN: 9781119085621

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621

Barragán-Medero, F., Martín-Hernández, A., Martínez-

Murciano, M. C., & Contreras-Madrid, A. I. (2024).

The vital role of grandparents in the education and

development of grandchildren in the contemporary

family. EduSer, 16(1).

https://doi.org/10.34620/eduser.v16i1.269

Döring, N., Mikhailova, V., Brandenburg, K., Broll, W.,

Gross, H.M., Werner, S., & Raake, A. (2022). Digital

media in intergenerational communication: Status quo

and future scenarios for the grandparent-grandchild

relationship. Univers Access Inf Soc., 3, 1-16.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-022-00957-w

Fingerman, K., Huo, M. & Birditt, K.S. (2020). A Decade

of Research on Intergenerational Ties: Technological,

Economic, Political, and Demographic Changes.

Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 383-403.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12604

Flamion, A., Missotten, P., Marquet, M. & Adam, S.

(2019). Impact of Contact With Grandparents on

Children's and Adolescents’ Views on the Elderly,

90(4), 1155-1169. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12992

Forghani, A., & Neustaedter, C. (2014). The routines and

needs of grandparents and parents for grandparent-

grandchild conversations over distance. In Proceedings

of Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, pp. 4177–4186. Simon Fraser University,

Canada. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557255

Gallagher, C. (2019). The changing lives and relationships

of young children and older adults: Implications for

intergenerational learning. Intergenerational Learning

in Practice. Routledge. ISBN 9780429431616.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429431616-2

Harwood, J. (2007). Understanding communication and

aging: Developing knowledge and awareness. SAGE

Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/

9781452225920

Ivan, L. & Fernández-Ardèvol, M. (2017). Older people

and the use of ICTs to communicate with children and

grandchildren. Transnational Social Review: A social

IS4WB_SC 2025 - Special Session on Innovative Strategies to Enhance Older Adults’ Well-being and Social Connections

396

work journal, 7(1), 41-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/

21931674.2016.1277861

Jassogne, C., & Zdanowicz, N. (2020). Real or Virtual

Relationships: Does It Matter to Teens? Psychiatria

Danubina, 32(1), 172-175. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.

nih.gov/32890385/

Kanyal, M., Mangione, D. and Luff, P. (2024). The role of

grandparents in early education and care in the 21

st

century: a thematic literature review of the UK research

landscape. Norland Educare Research Journal, 2(1), 1-

22.https://doi.org/10.60512/repository.norland.ac.uk.0

0000042

Kaplan, M, Sanchez, M, Shelton, C, Bradley, L. (2013).

Using Technology to Connect Generations. Penn State

University & Washington D.C.: Generations United;

2013. Retrieved from https://aese.psu.edu/outreach/

intergenerational/program-areas/technology/using-

technology-to-connect-generations-report

Keary, A.; Garvis, S.; Slaughter, Y.; Walsh, L. (2024).

Young Children’s Play and the Role of Grandparents as

Play Partners during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Education Sciences, 14, 771-785. https://doi.org/

10.3390/educsci14070771

Lai, D.W.L., Li, J, & Bai, X. (2021). To be or not to be: the

relationship between grandparent status and health and

wellbeing. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 204-213.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02052-w.

Lyu, K., Xu, Y., Cheng, H., & Li, J. (2020). The

implementation and effectiveness of intergenerational

learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence

from China. International Review of Education, 66,

833–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09877-4

McConatha, J.T., McConatha, M. & DiGregorio, N. (2021).

Lessons from My Grandmother’s Garden:

Intergenerational Learning and Managing Type 2

Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and Clinical Research,

3(3), 55-58. https://doi.org/10.33696/diabetes.3.039

Mendelová, E. & Zelená, H. (2021). Grandparents and

Their Role In The Current Family, ICERI2021

Proceedings, pp.149-156. https://doi.org/10.21125/

iceri.2021.0088

Modin, B., Erikson, R. & Vågerö, D. (2013).

Intergenerational Continuity in School Performance:

Do Grandparents Matter? European Sociological

Review, 29(4), 858–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/

esr/jcs064

Nicholson, S. (2015). Peeking behind the locked

door: A survey of escape room facilities.

White Paper available at http://scottnicholson.com/

pubs/erfacwhite.pdf

Pasqualini, M., Di Gessa, G., & Tomassini, C. (2021). A

Change is (not) Gonna Come: A twenty-year overview

of Italian grandparents-grandchildren exchanges.

Genus 77, 33 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-

021-00142-6

Piper, D., Malik, S., Badger, A. N., Washington, C., Valle,

B., Strouse, G. A., Myers, L. J., McClure, E., Troseth,

G. L., Zosh, J. M., & Barr, R. (2023). Sharing culture in

a tech world: Grandparent–grandchild cultural

exchanges over video chat. Translational Issues in

Psychological Science. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/

tps0000358

PORDATA (2024). PORDATA retrata perfil da população

Portuguesa. Comunicado de imprensa. Available at

https://ffms.pt/sites/default/files/2024-

07/PR%20DIA%20POPULAÇÃO%202024_VF.pdf

Ramos, N. (2013). Relationships And Intergenerational

Solidarities – Social, Educational and Health

Challenges. In A. L. Oliveira (COORD.). Promoting

Conscious and Active Learning and Aging: How to

Face Current and Future Challenges? COIMBRA

UNIVERSITY PRESS. https://doi.org/10.14195/978-

989-26-0732-0_6

Soliz, J. & Harwood, J. (2003). Perceptions of

communication in a family relationship and the

reduction of intergroup prejudice. Journal of Applied

Communication Research, 31(4), 320–345.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369681032000132582

Stephan, A.T. (2024). How Grandparents Inform Our

Lives: A Mixed Methods Investigation of

Intergenerational Influence on Young Adults. J Adult

Dev 31, 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-023-

09446-7

Strom, R. & Strom, P. (2015). Assessment of

Intergenerational Communication and Relationships.

Educational Gerontology, 41(1), 41-52. https://doi.org/

10.1080/03601277.2014.912454

Trujillo-Torres, J.M., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M.P.,

Mentado-Labao, T., & Barrera-Corominas, A. (2023).

Intergenerational Learning and Its Impact on the

Improvement of Educational Processes. Educational

Science, 13(10), 1019-1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/

educsci13101019

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2015). Learning

Families: Intergenerational Approaches to Literacy

Teaching and Learning. Germany: Institute for Lifelong

Learning. ISBN 978-92-820-1199-7. Retrieved from

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234252.

Wei, X., Gu, Y., Kuang, E., Wang, X., Cao, B., Jin, X. &

Fan, M. (2023). Bridging the Generational Gap:

Exploring How Virtual Reality Supports Remote

Communication Between Grandparents and

Grandchildren. CHI '23: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pp.1-15. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581405

Yuan, Y., Jin, Q., Mills, C., Yarosh, S. & Neustaedter, C.

(2024). Designing Collaborative Technology for

Intergenerational Social Play over Distance.

Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer

Interaction, vol. 8(2), pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/

10.1145/3687031

Bridging Generations: The Role of Digital Media in Fostering Intergenerational Collaboration and Knowledge Exchange

397